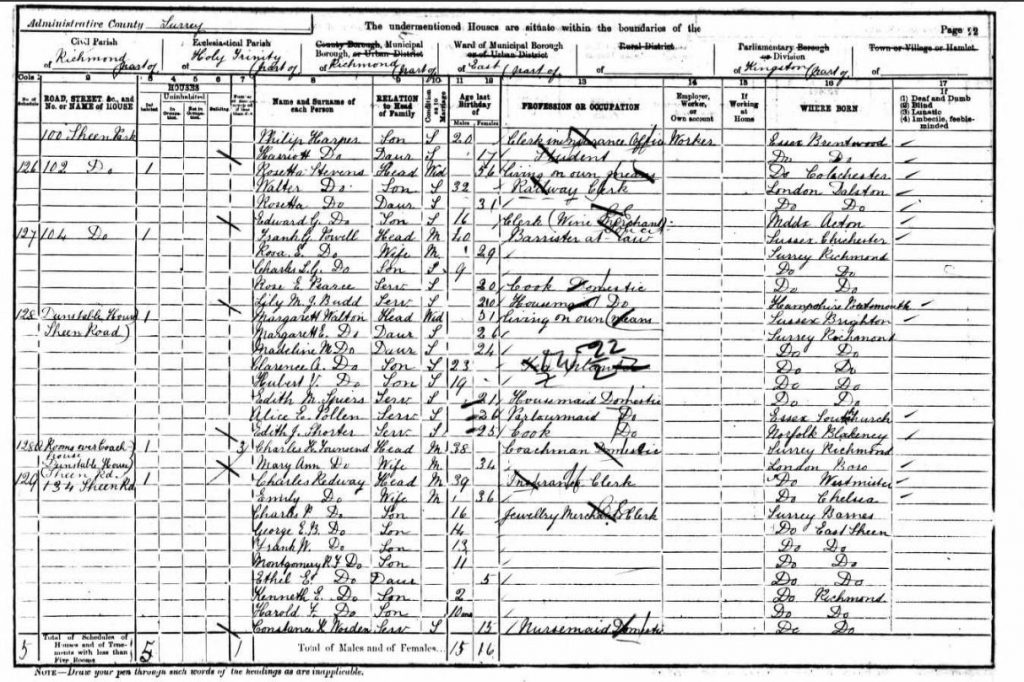

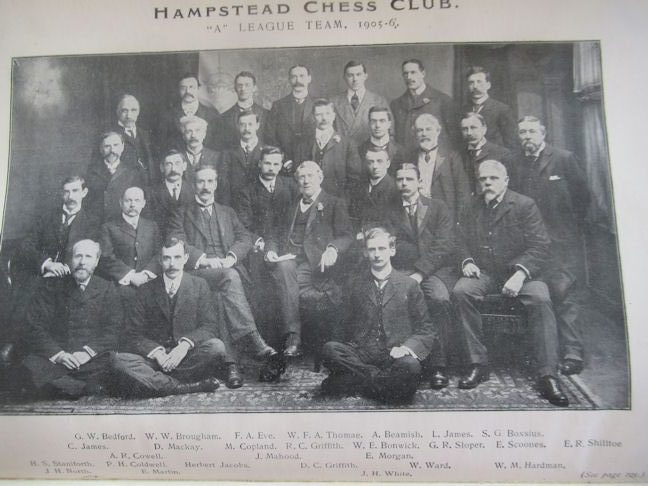

Last time we left William Ward at the time of the 1901 census, where he was staying overnight with one Isidore Wiener.

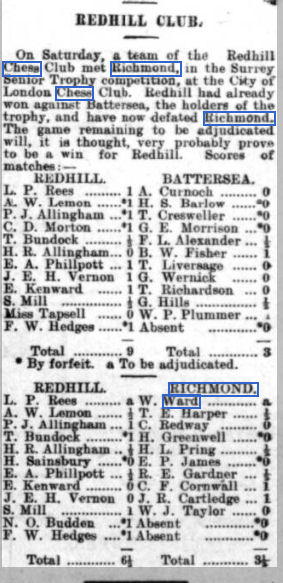

As we know he played for Richmond at the end of 1902, was he living in our part of London at that time?

But before that, in April 1902 William Ward played a match against rising American star Frank Marshall, who was visiting London at the time. The two players had met the previous year in the Anglo-American Cable Match, where Ward was successful. In this match, however, Marshall won four games to Ward’s two. The American was noted for his attacking skills but in this game he had no answer to his opponent’s kingside attack. (As usual, you can click on any move and a pop-up window will appear, enabling you to play through the game.)

This season also witnessed William Ward’s first success in the City of London Chess Club Championship. It appears that he and Thomas Francis Lawrence shared first place, but that Ward won the play-off.

In the summer of 1904 Ward played a match in London against George Edward Wainwright, winning by a score of 5½-3½.

In this game Wainwright had the better of the opening, but, playing too fast, perhaps, miscalculated on moves 30 and 31, giving Ward the chance of a crisp finish.

The inaugural British Chess Championships took place in Hastings in 1904, giving masters an amateurs alike the chance for a two week summer chess holiday. William Ward didn’t play that year, but was selected for the Championship in Southport the following year.

Ward started slowly, losing his first three games, followed by a draw with Blackburne, before winning six in a row, finishing with a draw against Atkins, who ran out the clear winner on 8½/11. Ward’s score of 7 points was enough for a share of second place with another forgotten player, Charles Hugh Sherrard.

In this game he again demonstrates his affinity with the Queen’s Gambit.

The 1905-6 edition of the City of London Chess Club Championship was another big success for William Ward, his score of 10½/13 putting him two points clear of the field.

By now he had developed notable skill in building up a slow attack from a closed position. He missed the chance of a brilliancy in this game, but his opponent gave him another, simpler, opportunity a few moves later.

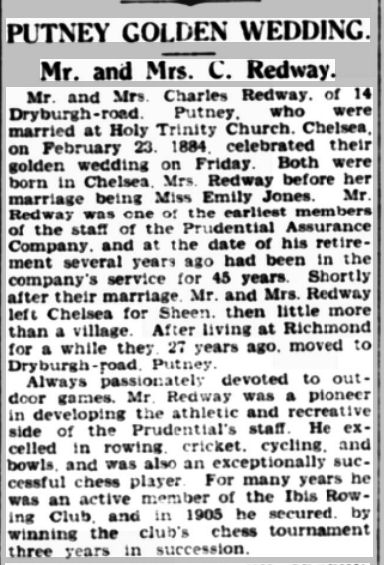

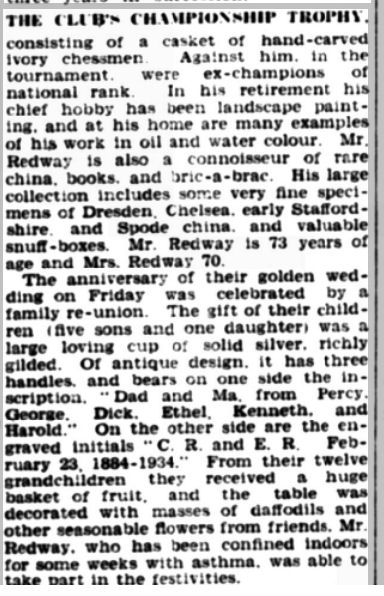

At some point round about 1905 Ward seems to have moved to North London, joining the Hampstead Chess Club, for whom he played successfully in the London League in the 1905-6 season. You can see him here, second from the right in the row of gentlemen seated on chairs.

The summer of 1906 was quiet: perhaps he was too busy with his legal work to take part in the British Championships in Shrewsbury. In the 1906-7 City of London Championship he failed to repeat the previous year’s success, sharing 3rd place behind the runaway winner George Edward Wainwright, with Hector William Shoosmith in second place.

William Ward didn’t have far to travel for the 1907 British Championships, which took place in Crystal Palace, but he failed to repeat his success of two years previously: this time he only managed 3½/11, sharing the tournament basement.

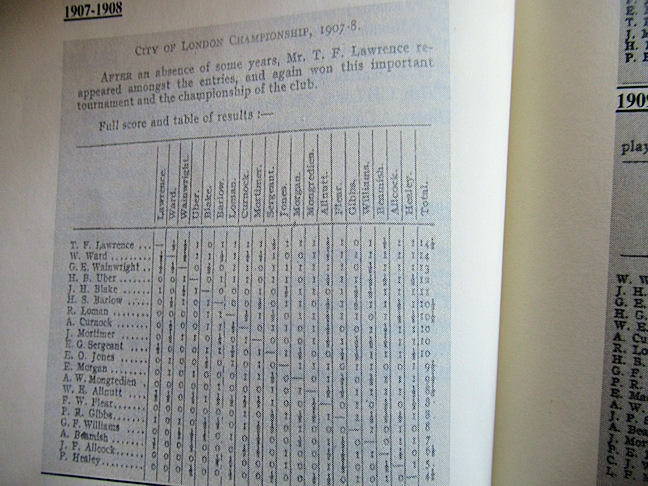

The 1907-8 championship of the City of London club provided a hat trick for players associated with Richmond Chess Club. Thomas Francis Lawrence won, with Ward and Wainwright taking the places.

In this game Ward experimented with what would much later become known as the Taimanov Variation of the Sicilian Defence, winning when his opponent failed to refute his unsound combination.

The 1908 British Championship took place in Tunbridge Wells, and, despite his result the previous year, he was again selected for the championship itself.

In the first two rounds Ward scored 2/2 with the Sicilian Dragon. It’s clear from this, admittedly not entirely accurate, game that he was well aware of the latent power of the fianchettoed bishop.

This was the game which, in some ways, defined William Ward’s life. He exceeded the time limit on move 19 (the first time control was, strange as it might seem by today’s standards, on move 20) in a clearly better position. Atkins eventually won the title, finishing on 8/11, with Ward in second place on 6½/11. If he’d won the game, the title would have been his. Unlucky: perhaps he was distracted by the photographer!

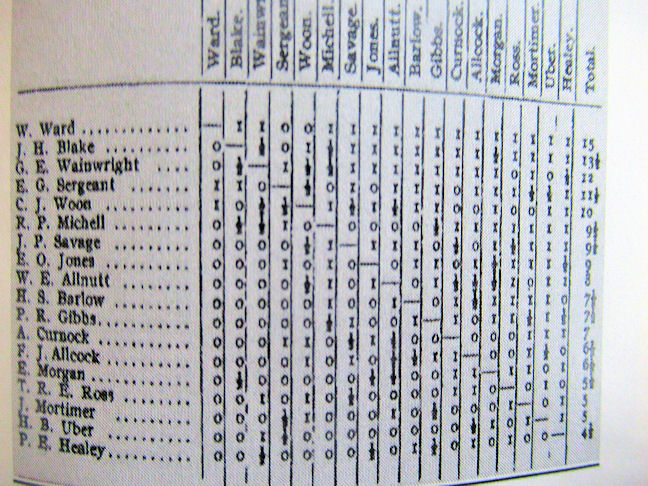

The 1908-9 City of London Championship gave Ward his third title with an impressive score of 15/17 (no draws!), including wins over his nearest rivals, Blake, Wainwright and Edward Guthlac Sergeant, all players connected at some time in their lives with the Kingston area.

The 1909 British Championships took place in Scarborough: Atkins and Blake shared first place on 8½/11, with the Leicester born schoolmaster Atkins winning the tie-break. William Ward took third place a point behind, again, losing a game on time on move 19, this time against Blake. Admittedly on this occasion he stood rather worse. One wonders what was the reason for his problems with clock handling in these games.

Here’s a long and exciting game against the young Fred Yates, in which he opened 1. e4 with White and met 1. e4 with e5 rather than the Sicilian.

As we move towards 1910 we can summarise William Ward’s chess career up to this point.

Now 42 years old, he was generally recognised as one of the strongest players in the country, having represented his country in five Anglo-American cable matches, having played four times in the British Championship, finishing in second place twice and in third place once, and having won the prestigious City of London Chess Club Championship on four occasions.

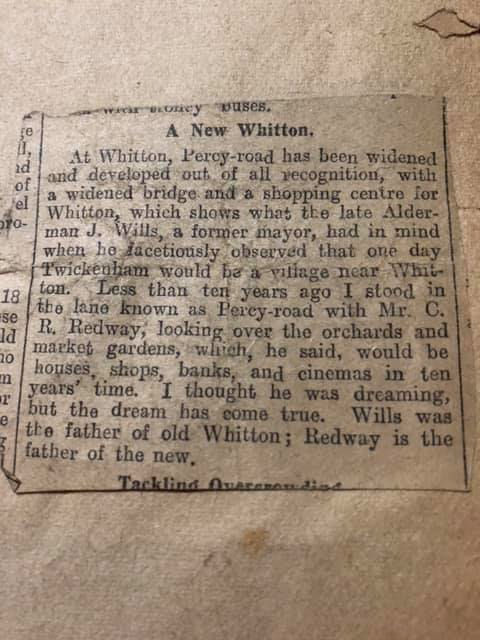

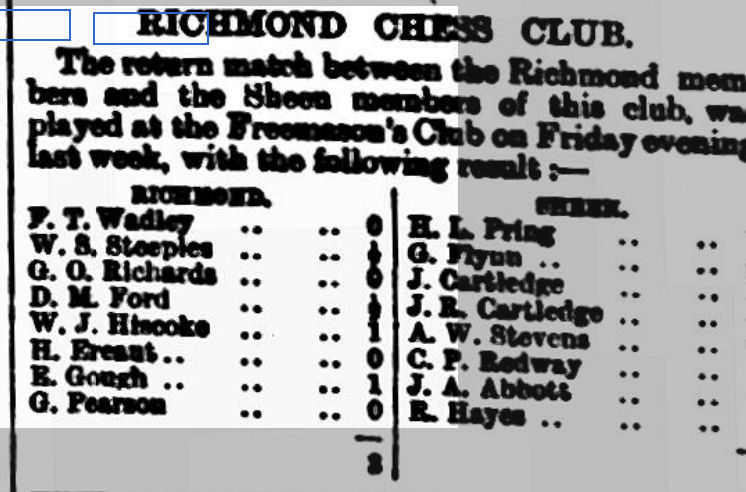

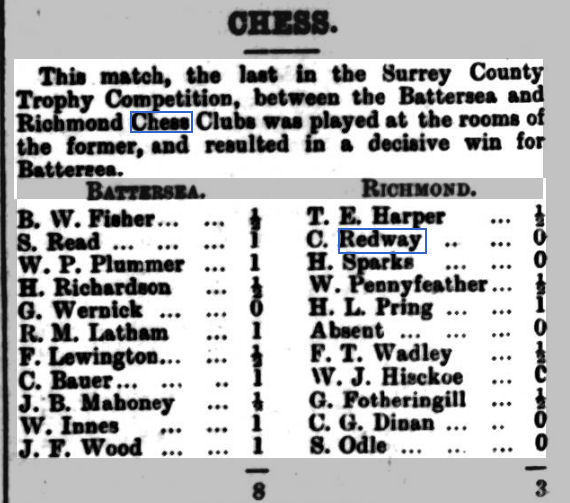

He played regularly for Middlesex, and occasionally for other counties, his home county of Hertfordshire, and also appearing on occasion for Kent and Sussex. As well as playing regularly for City of London he represented a number of other clubs: Richmond, Hampstead and West London, for example, as well as the National Liberal Club: was that an indication of his political views, I wonder?

He was increasingly being called upon to give talks and simultaneous displays, so seems to have been a well respected member of the chess community as well as a formidable player.

Rod Edwards’ retrospective 1909 rating list makes interesting reading: the leading English players, according to his calculations (and excluding the English-born Horatio Caro, who played most of his chess in Germany) were:

21. Atkins 2508

28. Burn 2485

56. Ward 2428

66. Richmond 2411

69. Blackburne 2405

79. Yates 2392

88. Blake 2384

92. Thomas 2379

101. Lawrence 2375

102 Gunsberg 2374

104 Shoosmith 2371

108 Wainwright 2362

120 Griffith 2354

123 Wahltuch 2353

131 Michell 2350

The veterans Burn, Blackburne and Gunsberg had been world class players in their day, but their peak had been back in the 1880s. Yates and Thomas, on the other hand, would only reach their peak in the 1920s.

The unfamiliar name here might be George William Richmond, at this point about to move to Scotland, who was strong but played in very few competitions.

Join me next time to find out what happened next to William Ward in the last of this series of articles.

Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

BritBase

EdoChess (Ward’s page here)

British Chess Magazine

The City of London Chess Club Championship (Roger Leslie Paige): thanks to Paul McKeown for the book.

Graham Stuart for information on Ward’s games against Hampshire.