There are many of us who enjoy an intellectual challenge over the breakfast table. These days we might solve a crossword or a sudoku.

In the days before crosswords and long before sudokus, there were those who would solve a chess problem over breakfast. Many daily and weekly publications would carry a regular chess problem, and also provide lists of successful solvers, who were no doubt keen to see their name in print.

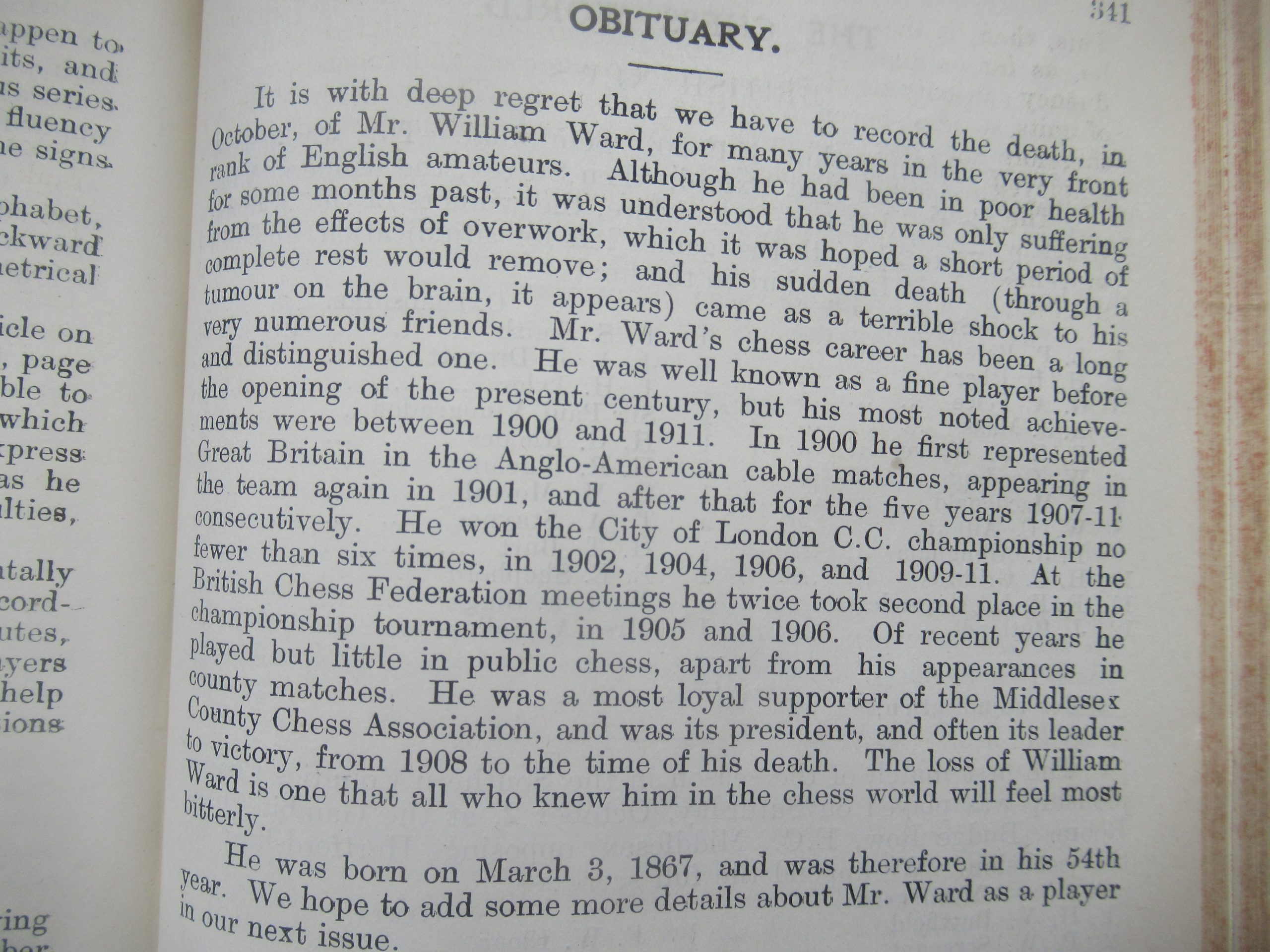

A name frequently seen in that context for more than four decades, from the 1890s to the 1930s was that of JMK Lupton (Richmond). Who was he? I was keen to find out, and I’m sure you are too.

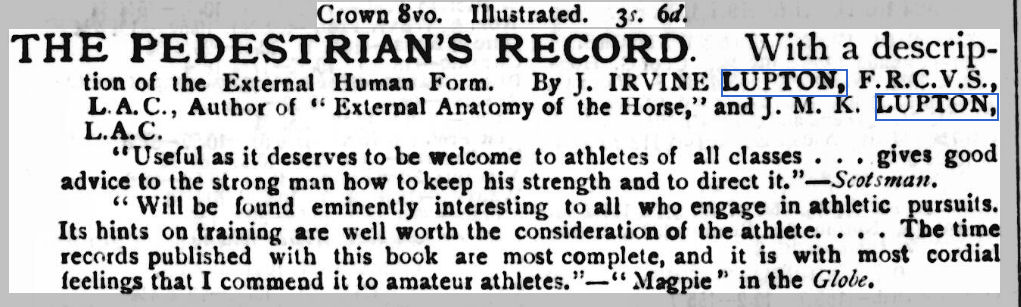

He was James Money Kyrle Lupton (middle names sometimes hyphenated), born in Richmond on 11 July 1864 and baptised at St Mary Magdalene’s Church in the town centre on 3 March 1865. He was the oldest of seven children. His father, James Irvine Lupton was a vet and the author of many books on the anatomy of horses. (Check out The Anatomy of the Muscular System of the Horse or Mayhew’s Illustrated Horse Doctor: Being An Account of the Various Diseases Incident to the Equine Race, With the Latest Mode of Treatment and Requisite Prescriptions for example.) His mother, Eliza Cheesman (sadly not Chessman), was the daughter of a vet.

I guess we need to consider his eccentric middle name(s). The Money-Kyrles are minor aristocrats, but I can find no immediate connection with either side of the Lupton family. Perhaps they were friends: who knows?

In 1871 the family, James, Eliza, James junior and four young daughters, are living at 20 Whitchurch Villas, Mount Ararat Road, Richmond, employing a housemaid, a cook and a nurse. Mount Ararat Road is one of the roads leading up from the town centre to St Matthias Church on Richmond Hill.

By 1881 the family have moved to Sheen Park (possibly No.4 but the census record isn’t exactly clear). James, like his now six siblings, is a Scholar, and the household is completed by a governess and three servants.

By this point he has already made his first appearance in a newspaper: the previous December the Surrey Comet reported that his cock had won second prize. Stop sniggering at the back there: it was a poultry show. The following June his rabbit was highly commended in a rabbit show.

It looked like he was going to follow in his father’s footsteps working with animals, but he soon took up another interest instead: athletics. He joined the London Athletic Club (his father was also a member) and for the rest of the decade the papers were full of his results, running distances up to 440 yards (the equivalent of 400 metres in today’s money – or should that be Money-Kyrle?). He also played tennis there, but with less success.

Combining his interest in running with his father’s interest in anatomy, the two of them wrote a book published by WH Allen & Co in 1890.

If you’re interested you can read it online here.

But at that point he seems to have retired from competitive athletics. What happened? Did he suffer an injury? Or did he just get bored and decide to move onto another interest?

The 1891 census finds the family in 3 Camborne Terrace, right by the river close to Richmond Bridge: a pretty desirable place to live. James Irvine’s veterinary practice and book sales must have provided the family with a more than comfortable income. Six of their seven children are still living at home: the oldest daughter, Maude, is in a boarding house in Littlehampton. James MK, now aged 26, seems, like his sisters, to be living a life of leisure, with no occupation listed. Roger is a clerk, and Horace is still at school. Now the children are almost grown, they only need to employ one domestic servant.

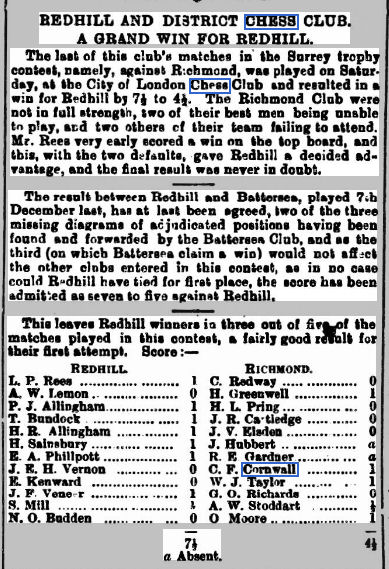

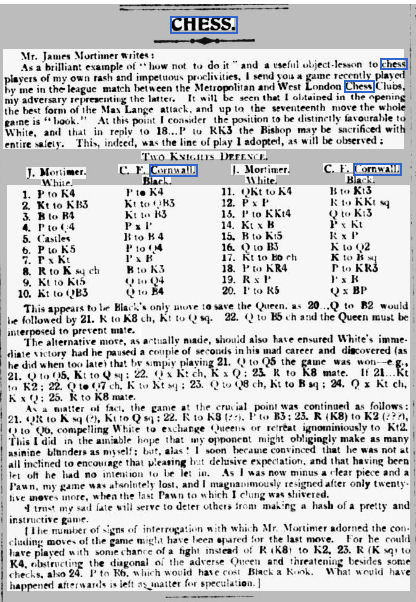

After the publication of his book his name disappears from the newspapers completely until 1893, at which point he’s taken up a new interest: chess problems.

His name starts appearing regularly as a solver in the Illustrated London News and the Morning Post, and it’s not long before he tries his hand at composition.

Problem 1

#2 The Field 28 Oct 1893

He’s also playing correspondence chess, with an extremely unimpressive game published against Hull schoolmaster George Wright Farrow. Click on any move for a pop-up window.

Lupton had a lost position from the opening. If he’d read Chess Openings for Heroes he’d have avoided that variation.

Then Farrow, having been winning all along, first throws away the win on move 40 by choosing a passive rook move, then miscalculates the pawn ending, missing a draw on move 44. If he’d read Chess Endings for Heroes he wouldn’t have made those mistakes.

Lupton is very active, both as a solver and a composer, for several years in the middle of the 1890s. Here’s one from later in the decade.

Problem 2

#2 The Field 19 May 1897

But after that his name appears less often, with only very occasional compositions.

By 1901 it’s time for the census enumerator to call round again. Something unexpected has happened. He’s left home and found a job. Not the job you’d expect, either. He’s a police constable, lodging in Streatham with a working-class couple in their 60s, Henry and Caroline Mynott. I suppose that, whether through choice or necessity, finding employment would give him less time for chess problems. For whatever reason, it must have been quite a change from life with his affluent parents by the river in Richmond.

His father had died the previous year, but Eliza and her other six children, all, like James unmarried, are living in Halford Road, Richmond, near the bus station. None of the four girls have jobs listed, but Roger is a company secretary and Horace an accountant. Also there is Clara Cheesman, a 45-year-old widow, presumably a relative by marriage, although the Cheesman family has so far proved very elusive.

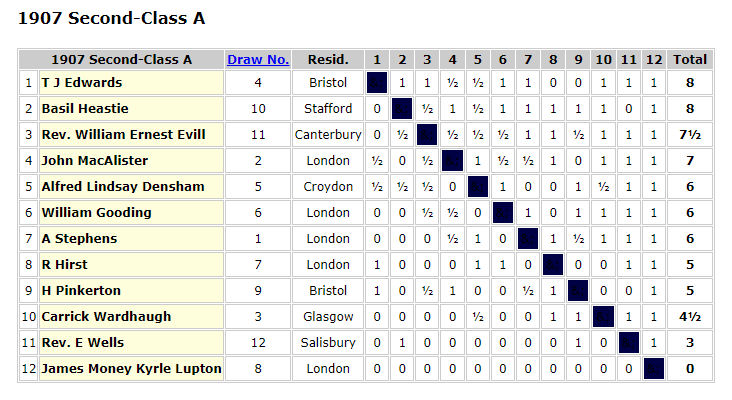

Eliza would die two years later, in 1903, and Horace, sadly, later the same year, aged only 29. By 1905 James was starting to regain an interest in chess. In the same year his spaniel Rose O’Brady took a second prize at the Kennel Club Dog Show (‘a nice coloured and sound spaniel, but her coat might be better’). By the following year he was both solving regularly and composing again, ambitiously moving up to 4-movers as well as 2- and 3-movers. Perhaps he was no longer a police constable so had more time for chess.

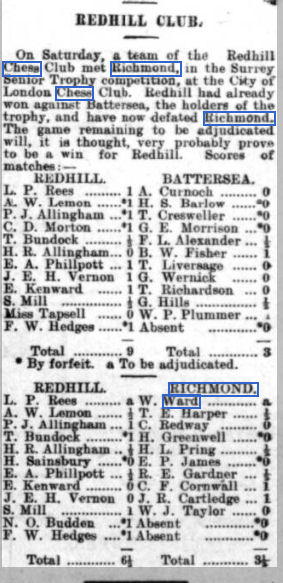

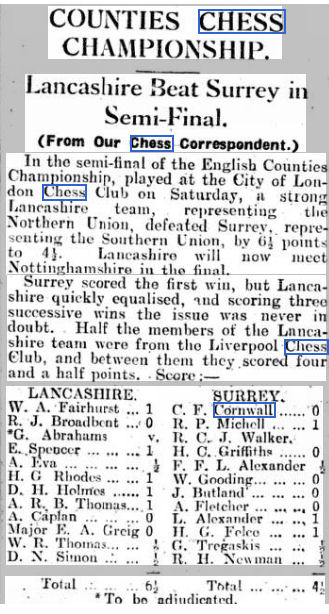

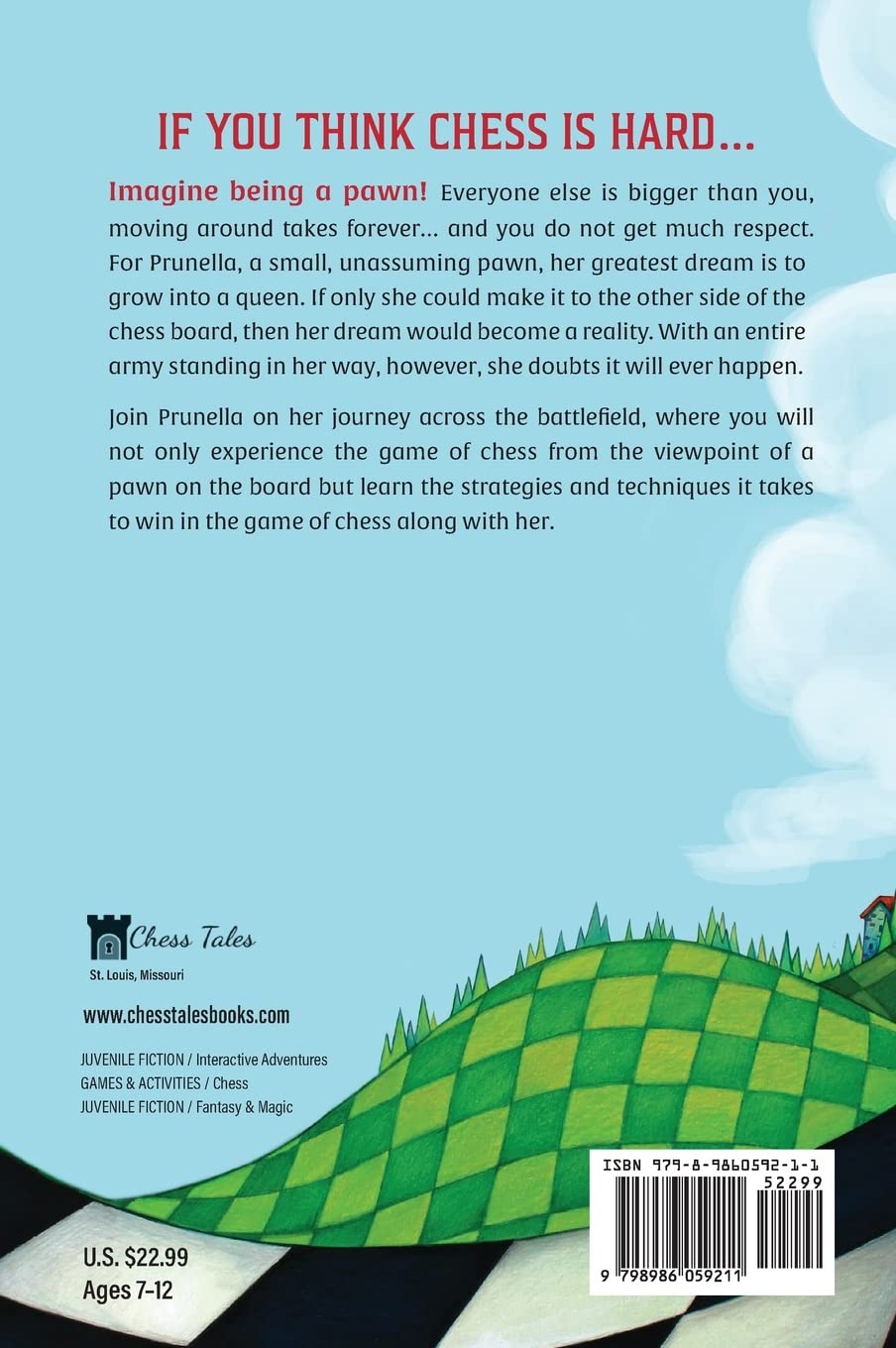

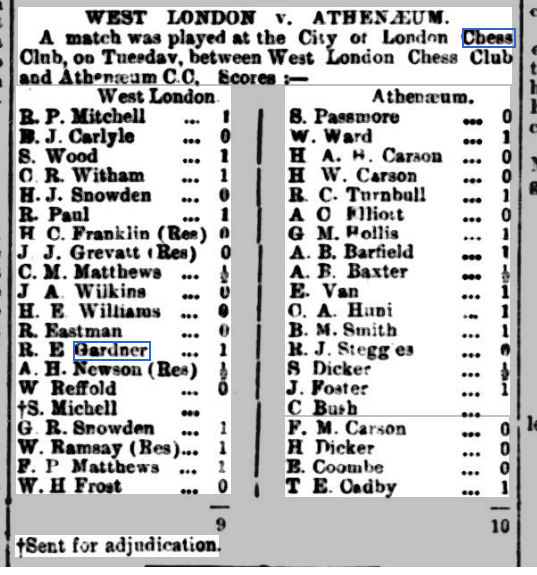

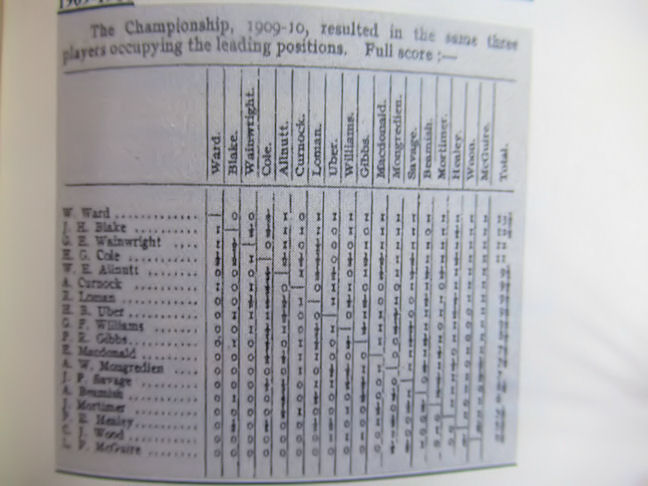

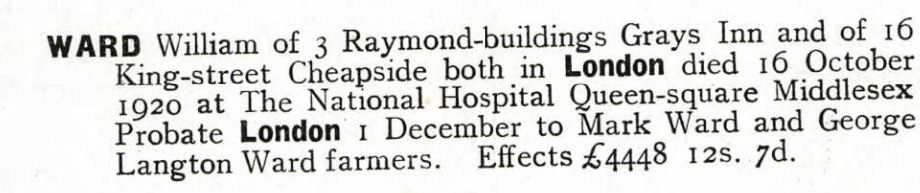

I have yet to see any evidence that he was a member of his local chess club in Richmond at this time, but club reports for this period are thin on the ground. However, in 1907, with the British Championships taking place in London, he decided to try his hand, and was duly entered into the Second Class A section, along with my favourite chess playing clergyman, Rev Evill. (I see Evill drew with Gooding, which must prove something, but I’m not sure what. Perhaps it was the chess equivalent of this cricket match.)

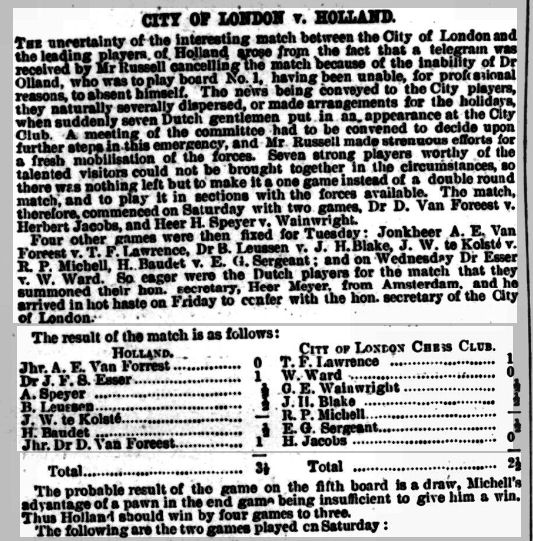

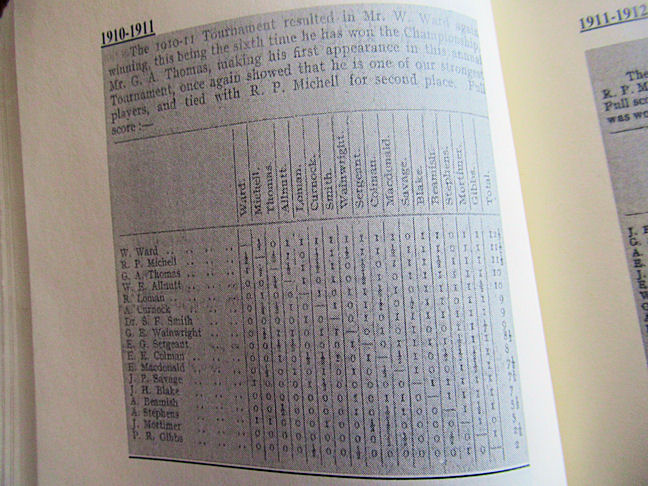

Lupton’s participation didn’t go well, as you’ll see from the cross-table.

It’s not clear, though, whether he actually played all his games or lost some (or perhaps all) by default.

He continued solving and occasionally composing until 1909, after which his name disappeared again.

By 1911 we find him back in Richmond, and in a different job. He’s no longer a police constable but an advertising agent. He’s still boarding, with a milkman and his family, in Eton Street, right in the town centre.

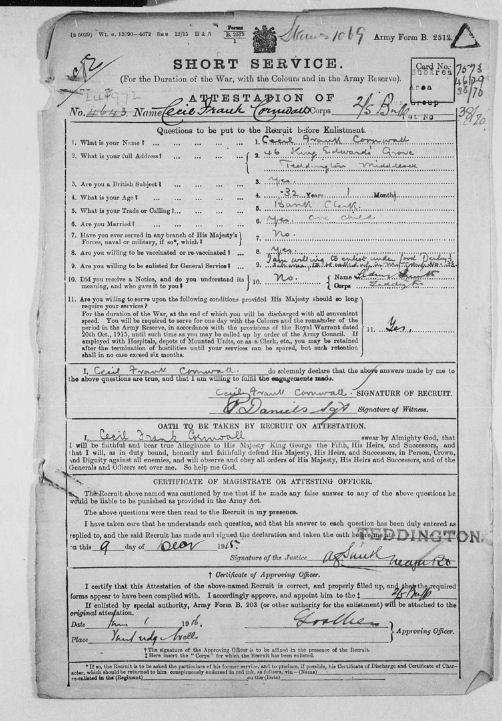

Throughout the 1910s there’s no record of him at all. It’s ten years before we get to meet him again, in the 1921 census.

Now approaching his 57th birthday, he’s lodging at 31 Sheendale Road, Richmond, which runs south off what is now the A316 towards the railway line. His occupation is described as ‘Ex Officer of Police London County Council Constabulary’, his employer as ‘Pelabon Works East Twickenham’ and place of work as ‘shell factory’. Well, it had been some years since he’d been an officer of police, but the Pelabon Works were very interesting.

About 6000 Belgian refugees were living in East Twickenham during the First World War, many of them working at a munitions factory run by a French engineer named Charles Pelabon. Although most of the workers there were Belgian, some English workers were also employed there, and James Money Kyrle Lupton must have been one of them. It’s a fascinating story: you can read more about it here (a paper from the scholarly journal Immigrants & Minorities: Historical Studies in Ethnicity, Migration and Diaspora) and here, amongst other places. The factory was later converted into the world famous Richmond Ice Rink.

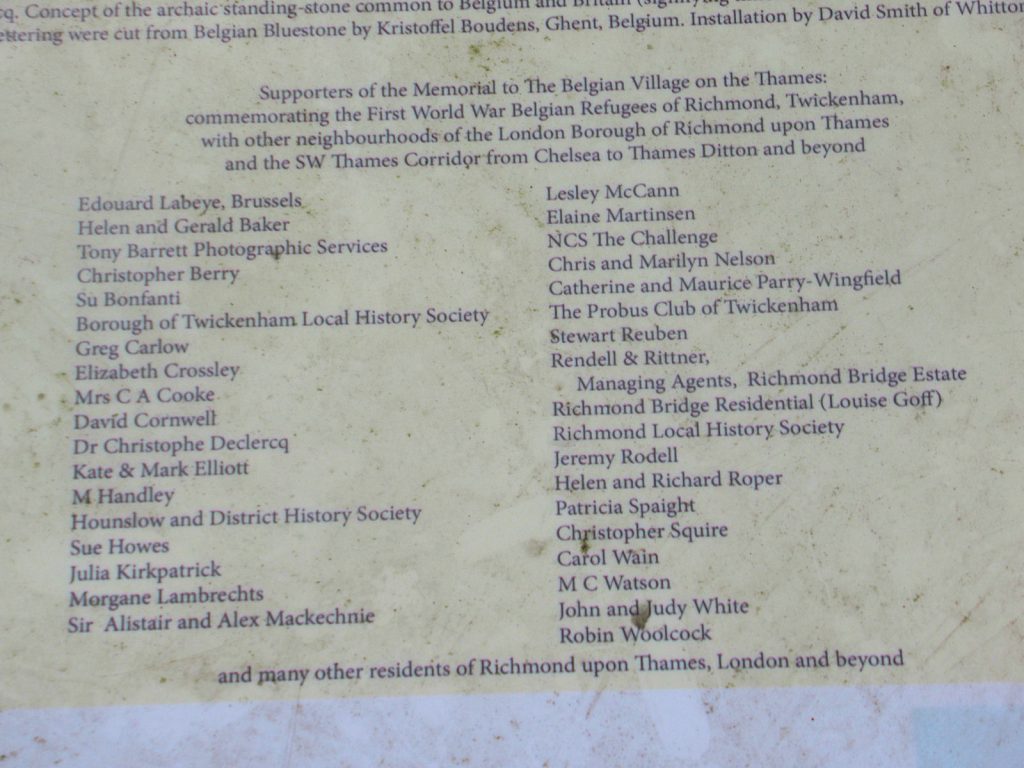

If you take the bus to Richmond Bridge and stroll along the river on the Middlesex bank towards the centre of Twickenham (a short walk I can highly recommend) you’ll soon come across a small garden with two information boards, one telling the story of the Belgian refugees, and one the story of the ice rink.

Here’s the Belgian refugee board: you’ll have to visit yourself to read all the text.

And here’s a list of local residents who made financial contributions to support the memorial. You’ll see a very familiar name on the list, although he has now moved out of the area.

At some point he also had a job working for the Parks Department of London County Council, which may have been in the early 1920s, or possibly earlier.

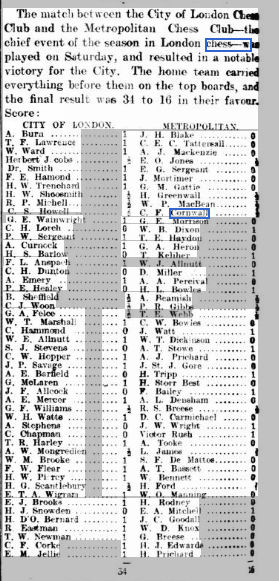

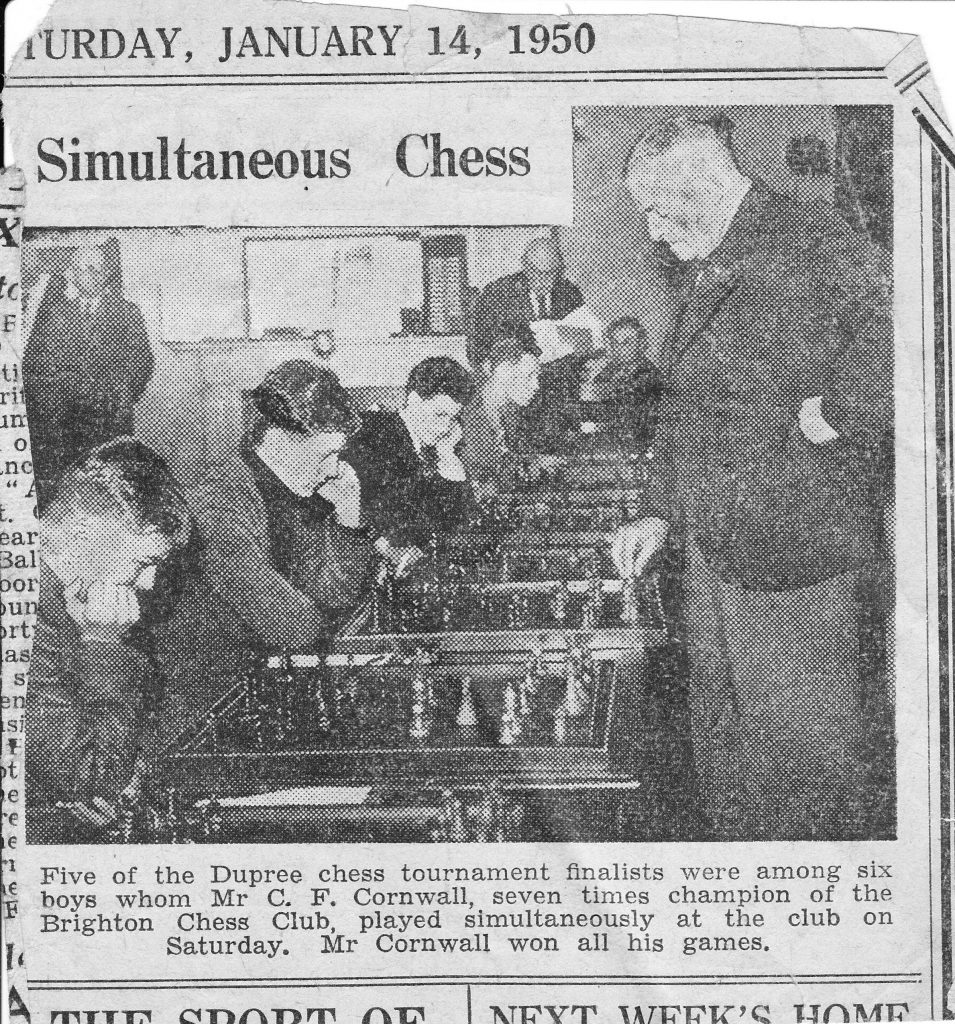

But living on his own, with no employment and nothing better to do with his time, in 1921 he decided to return to chess problems, with his name now regularly appearing in lists of solvers in the Illustrated London News, to whom he also submitted problems for publication.

On 24 September 1927 they were profuse in their gratitude: “You overwhelm us with your kindness. Your problems are quite unique, and they always possess a piquant interest peculiar to themselves.”

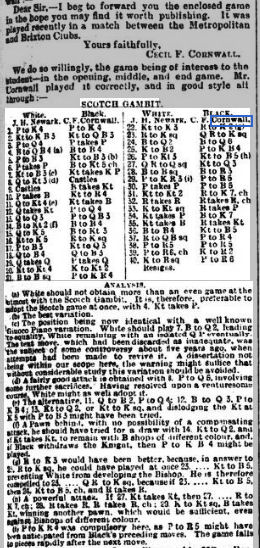

He also found a new outlet for his problems in the Catholic weekly The Tablet. While his ILN compositions were often complex waiters, where the key move created no threats but the many possible black replies all allowed different mates, The Tablet, whose readers were less likely to have a specialist knowledge of chess problems, was favoured with simpler problems, often featuring a theme popular at that level.

Here’s an example.

Problem 3

#2 The Tablet 8 Aug 1925

The ILN chess column was discontinued in 1932 (only resuming under BH Wood’s authorship in 1949) and Lupton’s last problem in The Tablet was published in 1933.

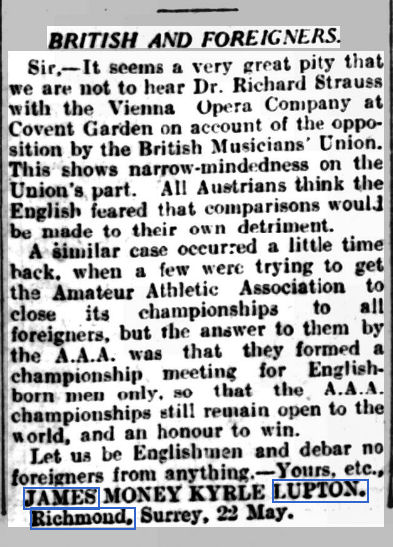

James Money Kyrle Lupton had also found a new hobby to while away the time: writing letters to newspapers. Here, in 1924, he exclaims “Let us be Englishmen and debar no foreigners from anything”.

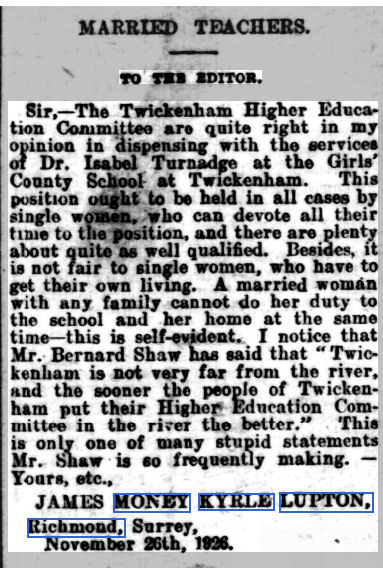

While he was in favour of foreign musicians such as Richard Strauss playing in England, he was strongly opposed to married women with children working.

There was a local cause célèbre in Twickenham in 1926 when the local Education Board, headed by Twickenham Chess Club President and British Fascist (he joined that year) Dr John Rudd Leeson, sacked the headmistress of Twickenham County School for Girls, Dr Isabel Turnadge, after she married and had a child.

George Bernard Shaw was not slow in voicing his opinion, and nor was Lupton.

However, the following year he came out in favour of lowering the voting age for women from 30 to 21. “Women are equal to men in a great many callings, and in some far better. The present voting age of 30 for women is an insult to womanhood.” (Westminster Gazette 06 April 1927) Strangely, I haven’t been able to find him on any electoral roll (the only family member I’ve identified there is his brother Roger), possibly in part because he never owned his own property.

By the 1930s he’d become Mr Angry of Richmond. I suspect that today, like many sad and lonely middle-aged men, he’d be a Twitter Troll. He was a passionate supporter of capital punishment, for rapists and paedophiles as well as murderers, and was strongly opposed to releasing prisoners with life sentences after 20 years. He also held strong views about non-pedigree dogs: “Curs and mongrels are valueless, and are the Communists of the dog world, and emissaries of the devil” (West London Observer 10 November 1933). He complained about cars driving too fast in Richmond Park (still a hot topic today), children playing football in Kew Gardens, jaywalking pedestrians (women were the worst), about British Summer Time. There was always something to complain about. But most of all he complained about people talking: in libraries, in cinemas, on trains. In one of his last letters he wrote that brunettes were better than blondes, although I’m not sure how much experience he’d had of either.

He retained his membership of the London Athletic Club, often walking from Richmond to the city and back (24 miles) in a day, and often wrote letters about his favourite sport, as well as about horse riding. He thought women would make excellent jockeys, as indeed they do: witness the likes of Hollie Doyle and Rachael Blackmore.

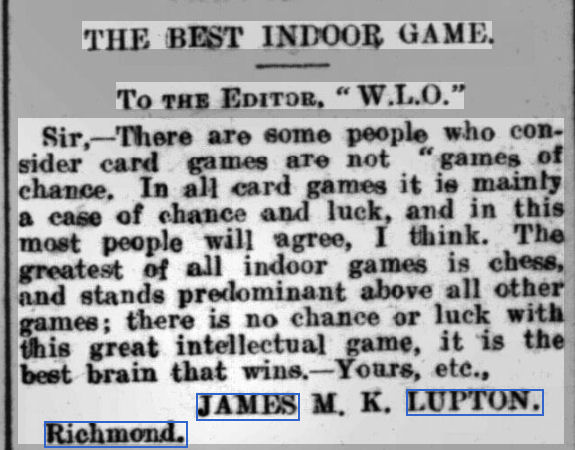

In 1934 he wrote a letter about his favourite indoor game.

Looking back at his results in the 1907 British Championships, I’m not sure what that says about James MK Lupton’s brain.

Although his chess composing career seems to have come to an end in 1933, he continued writing letters to newspapers until 1936. While some of his views seem relatively enlightened for the time, many of them were extremely reactionary. He died on 12 April 1937 at the age of 72. His address was given as 34 Halford Road Richmond, where I suspect he was back living with his sisters, but he died at a nearby address, 22 Cardigan Road, a very large house which might, at the time, have been a clinic or care home of some sort. He left £351 15s 7d and probate was granted to his sister Maude.

Reading between the lines, I get the impression that James Money Kyrle Lupton probably didn’t have a very happy life. He came from an affluent background, and had a talent for sports, writing and chess, but never seemed to settle in one job and never owned his own property, spending much of his time living in lodgings. Looking at his letters, he seems to have become rather grumpy and cantankerous in later years. Perhaps he should have joined Richmond Chess Club and made some friends.

Did something go wrong at some point? Who knows? The family hasn’t been well researched and there seemed no online tree available so I created one myself. They all, especially on the Cheesman side, seemed difficult to track down There’s something unusual, but not unique (you’ll meet a similar example in a future Minor Piece), about the Lupton family. All seven of the siblings reached adulthood but none of them married or, as far as I can tell, had children. Three of his sisters lived very long lives, two into their nineties and one to her mid eighties. While James was only too keen to see his name in print, the rest of them seemed a pretty reclusive bunch.

If you want to see more of his problems, you’ll find those from The Field and The Tablet in Brian Stephenson’s MESON chess problem database. I also used one of them as the Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club Puzzle of the Week. If you search online newspaper archives you’ll find quite a few more, from the Illustrated London News and other sources.

That, then, was James Money Kyrle Lupton, athlete and chess problemist. Join me soon for another Minor Piece.

Solutions:

Problem 1:

1. Bc8! (threat 2. d8N#). 1… e4 2. Qd5#, 1… f5 2. Rg6#, 1… Qxc5 2. Nxc5#, 1… Nd8+ 2. cxd8N#, 1… Rxe8 2. dxe8Q/R#, 1… Rxc8 2. dxc8Q/B#

Problem 2:

1. e5! (no threat). 1… f5/f6 2. exf6# 1… Bg7/Bh6 2. Re8# 1… Nb6/Na7 2. Ba3# 2… Nd6 2. exd6#

Problem 3:

1. Nf4! (no threat) 1… Kxf4 2. Qe4# 1… Kxf6 2. Qg7# 1… Kxd6 2. Qe7# 1… Kd4 2. Qd5#

The Star Flight theme. The black king has four diagonal flight squares, each of which is met by a different white mate.

Acknowledgements and sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

MESON chess problem database

BritBase

Twickenham Museum

Other online sources quoted within the article