Ralph Jackson won the Sydney Junior Championship back in 1976 and is currently ranked 7th among players in Australia born before 1960.

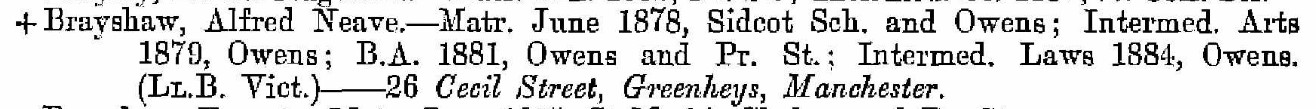

He is also intrigued by family history, and his interest was piqued in 2015 when a cousin showed him transcripts of letters his great grandfather’s brother had been sent by an English nephew in 1874 and 1875 concerning his family’s financial struggles, and his mother’s illness and subsequent death.

He idly, as one does, entered the name of his English relation, of whom he had previously been unaware, into Google and was both startled and delighted to discover that Antony Guest had been a prominent chess player and journalist. You could even make the case that he was the Leonard Barden of his time, and that, almost a century after his death, his influence can still be felt today.

When Ralph noticed that I’d mentioned Guest in an earlier Minor Piece he contacted me to ask what more I could discover about him. As he was on my list of future Minor Pieces, in part because of his local connections to me, I was more than happy to oblige.

The birth of Antony Alfred Geoffrey Guest (he didn’t use his rather splendid middle names for chess purposes) was registered in the second quarter of 1856 in Staines, Middlesex. His father Augustus was a schoolmaster, classicist and artist, the son of Thomas Douglas Guest. His mother Phoebe, also known as Elizabeth or Mary, was the daughter of refugees, originally from Eastern Europe, but who had arrived via Denmark. Although she was born in the Jewish faith she later converted to Christianity.

Antony was baptised by cricketing clergyman Henry Vigne in St Mary’s Church Sunbury on June 18 that year. Entirely coincidentally, I visited that church recently and took a few photographs.

I don’t know the age of the font on the left: the inscription records when it was moved, not when it was installed, but I’d guess it wasn’t the one in which baby Antony was baptised.

By 1861 the family, now joined by Isabella Katherine Celia Guest (who would later be known as Katherine or Kate), had moved to Thayer Street in central London, conveniently situated just a few yards from the Chess & Bridge Shop in Baker Street.

But on 20 June 1864 Augustus was admitted to Grove Hall Lunatic Asylum, where he died on 19 March 1866. The family were now struggling to maintain their previously affluent lifestyle, and Antony had to leave school early. By 1871 he was working as a clerk, while his mother was now a lodging-house keeper. Isabella was, for some reason, visiting a carter’s family in Hampshire.

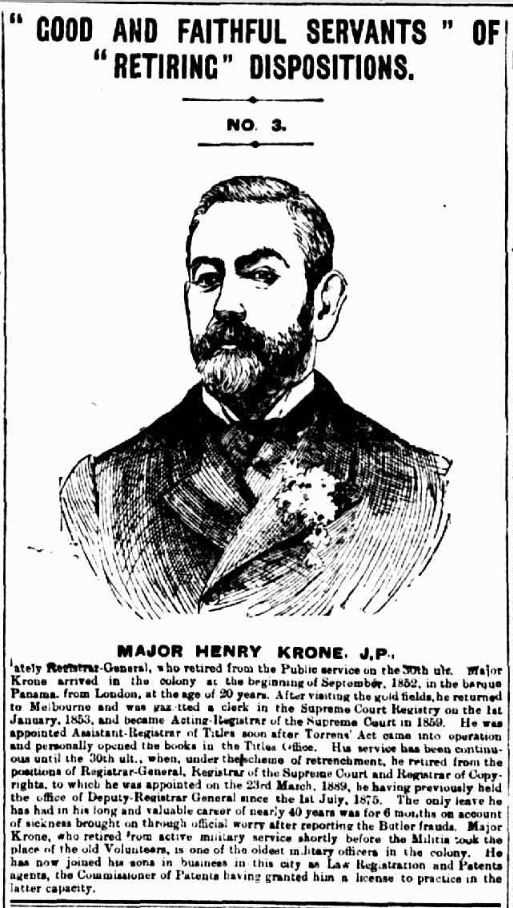

Meanwhile, Phoebe’s three brothers, Abraham (who changed his name to Alfred Lionel), Henry and Maurice had emigrated to Australia in the 1850s, seeking their fortune in the Gold Rush.

Henry, in particular, did very well for himself. After visiting the gold fields he took a job in public service, later rising to become Registrar-General of Victoria as well as attaining the rank of Major in the volunteer forces.

It was Uncle Alfred who was the recipient of Antony’s surviving (in transcript) letters.

The first letter Ralph has is from July 1874.

Circumstances have gone very hard with us of late, my mother has been very ill lately, and has been unwell for the last two years, and find it very very difficult to make ends meet-, especially since food and other necessities have become so dear, a little assistance therefore now and then would be a very great comfort to her.

In October he wrote again with the sad news that his mother had died of gastric (typhoid) fever the previous month.

My poor mother left her affairs in a very unsettled condition, her debts amounting to nearly 70 pounds, and my sister and myself would be greatly obliged to you or our uncle Henry for any assistance you could give us.

In December he informed Uncle Alfred that he had moved into a boarding house and his employer had lent him enough money to pay off his mother’s debts, but it appears that his family in Australia had been unable to help financially.

Ralph’s final letter, from April the following year, sees Antony telling his uncle that his prospects were now good, but thanking him for his offer of a home in Australia for his ‘delicate’ sister Isabella. If she took up the offer she wasn’t there long as she was back in England by 1881.

Here, then, was a formerly prosperous family that, due to illness and death, and perhaps also financial mismanagement, had hit hard times. Young Antony was doing his best to sort things out.

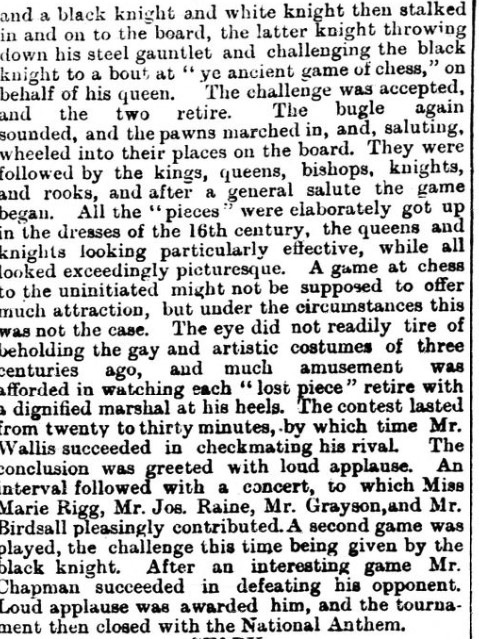

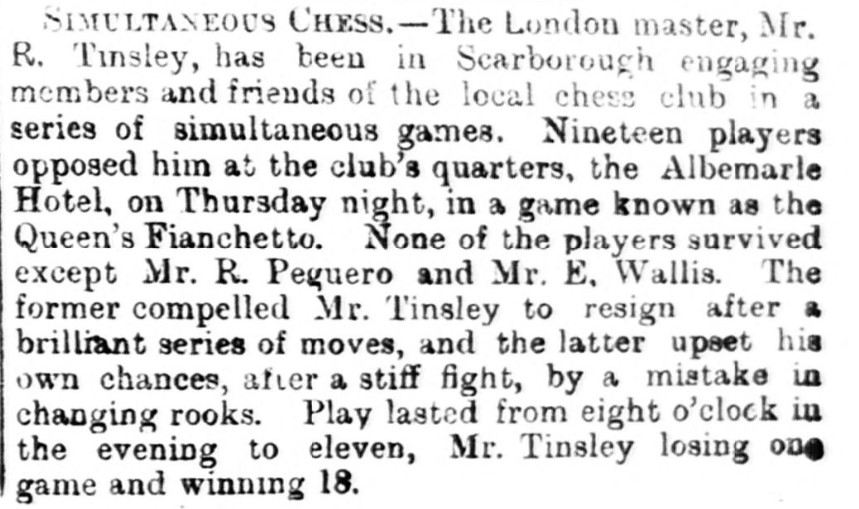

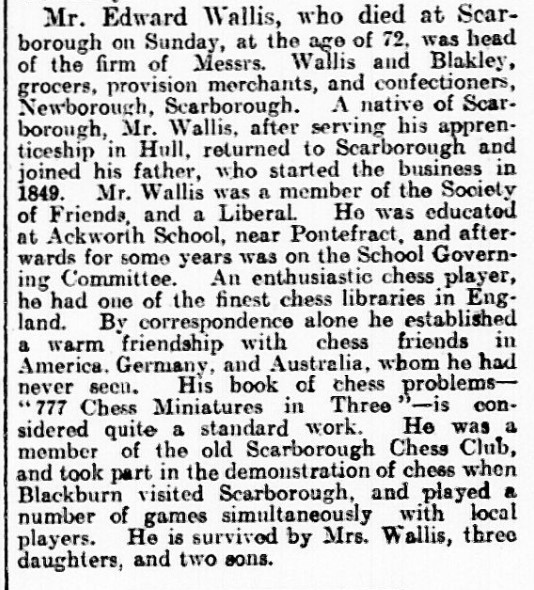

He also developed an interest in chess, watching one of the games in the 1876 match between Steinitz and Blackburne, and remembering, almost a quarter of a century later, how deeply absorbed he was.

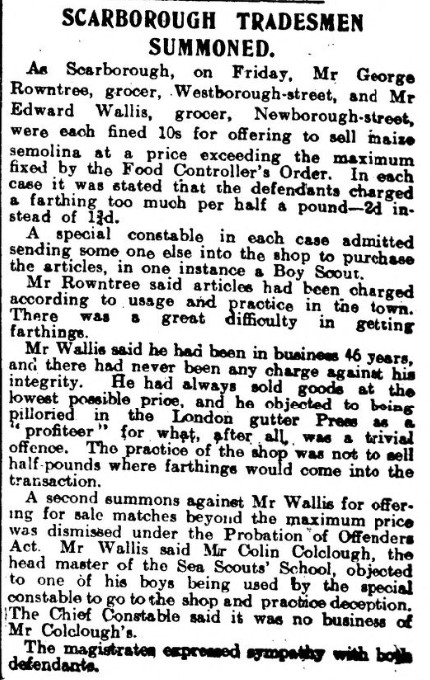

We next pick him up in 1880, when he applied to become a member of the London Stock Exchange. The 1881 census found him on holiday at the Grand Hotel in Brighton, giving his occupation as Stock Jobber. A Stock Jobber was a private trader in stocks and shares, as opposed to a Stock Broker who worked for clients. The Grand Hotel, according to Wikipedia, “was intended for members of the upper classes visiting the town and remains one of Brighton’s most expensive hotels”. He’d clearly turned round his family fortunes, then.

By this time, Antony was spending much of his spare time frequenting Purssell’s and other places where the game was played socially.

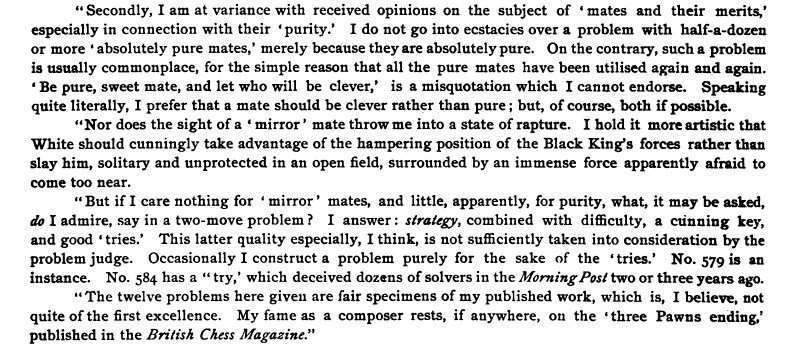

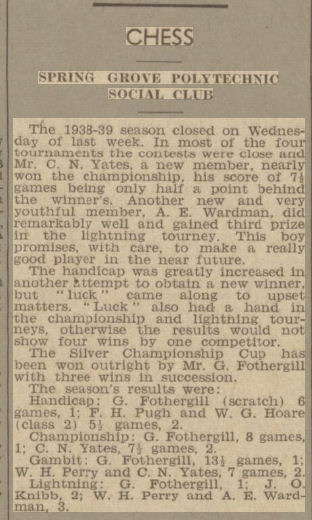

He also acquired a new job, as a journalist for the Morning Post, a Conservative daily newspaper which would be taken over by the Daily Telegraph in 1937. In 1883 a major international tournament took place in London and Antony was dispatched to report on it. His reports must have proved very popular as the paper commissioned him to start a weekly column, beginning on 28 May 1883.

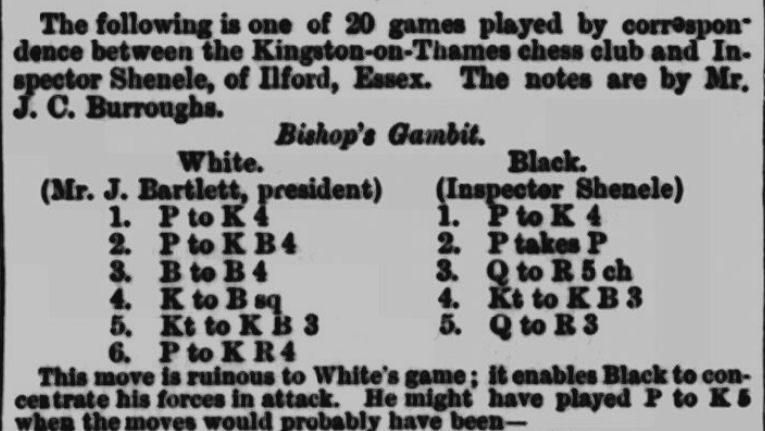

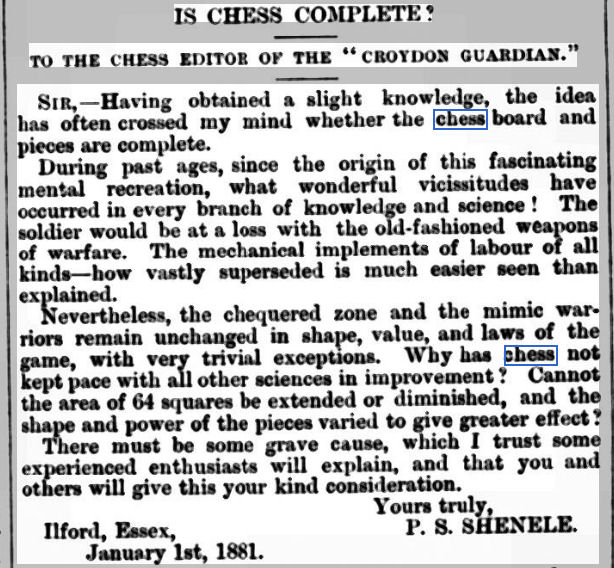

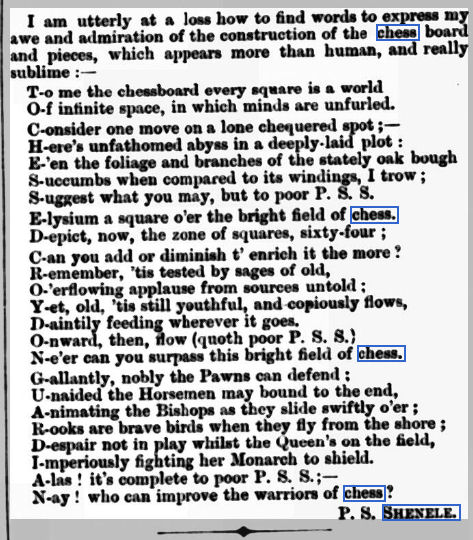

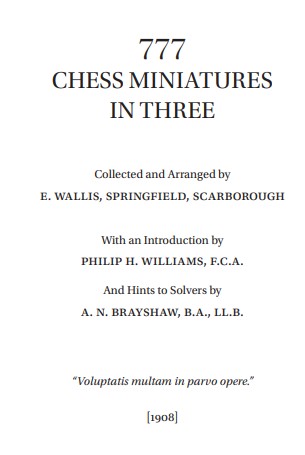

The column would typically include a problem (sometimes two) for solving, a list of successful solvers of the problem from two weeks earlier, a game, either contemporary or historical, news from home and abroad, answers to readers’ questions and, on occasion, book reviews, such as this one.

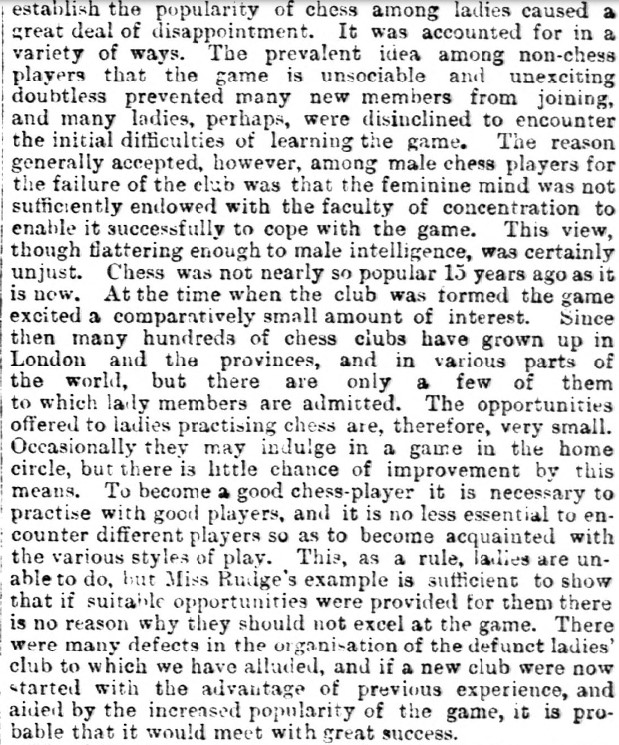

Guest was always very enthusiastic about promoting chess for ladies, so would have been pleased to support Miss Beechey‘s venture.

Although he was not yet playing in public, he started publishing a few of his own games later in the year. Here he gave his opponent odds of pawn and move (he played black without his f-pawn). As always, click on any move in the game for a pop-up window.

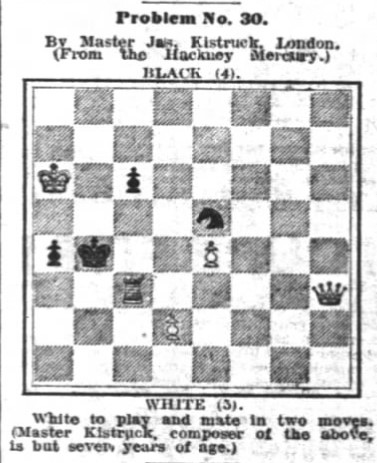

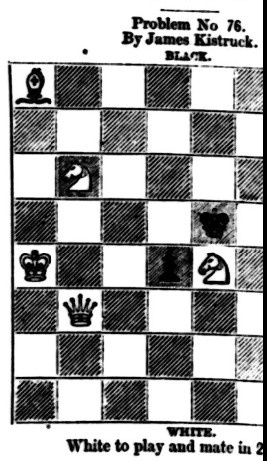

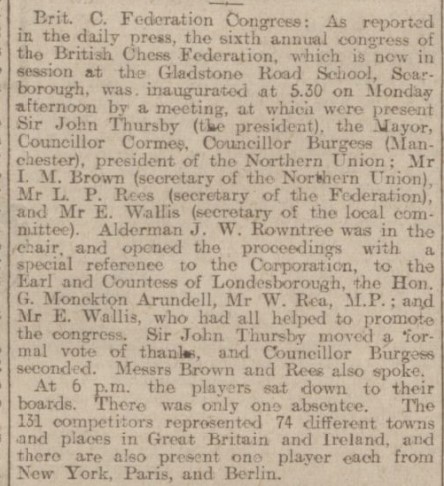

By 1884 he had also started to compose problems, at first in collaboration with future BCF President John Thursby.

You’ll find the solution to all problems at the end of the article.

Problem 1. #3 A Guest & J Thursby Morning Post 26-05-1884

At the same time he played in public for the first time, in a handicap tournament at Simpson’s. Here he was accepting odds of pawn and move from the masters, who, in his section, were Blackburne and Gunsberg. He won his section with 7½/9, but was beaten by Mason, also giving him odds, in the play-off between the winners of the two sections.

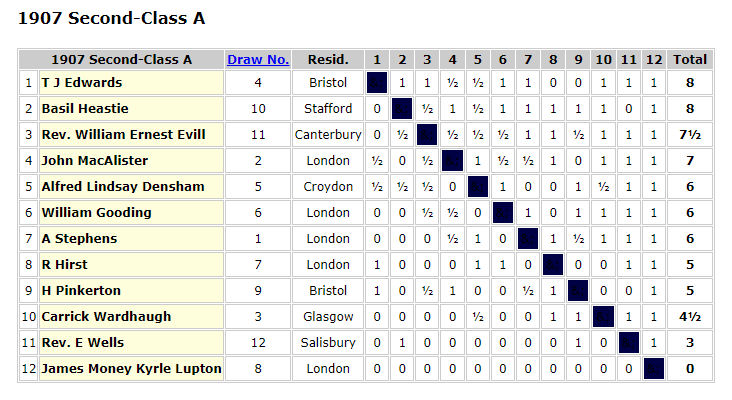

Buoyed by this success he took part in his first master tournament, an event run by the British Chess Association in London. His performance, considering his lack of experience, was rather remarkable.

Gunsberg, as expected, ran out a comfortable winner with 14/15, but Guest shared second place with Bird on 12/15.

In his game against Wainwright (see earlier Minor Pieces) he gave up the exchange in the opening but later trapped his opponent’s queen.

He won very quickly against Hewitt, who wasn’t given the chance to recover from a hesitation in the opening.

This was a most auspicious debut for a relatively young (by the standards of the day) player. It was probably anticipated that he would have a big future in master chess, but, as it turned out, his first high level tournament would also be his best result.

Later that year Guest was involved in an interesting debate with John Ruskin.

The debate as to whether chess should be on the school curriculum is still going on today, almost 140 years later. Unlike many of my colleagues in the world of junior chess, I’m very much in agreement with Guest here. Ralph Jackson shares our views.

Here’s another problem, this time a joint composition with Louis Desanges.

Problem 2. #3 A Guest & L Desanges Morning Post 16-11-1885

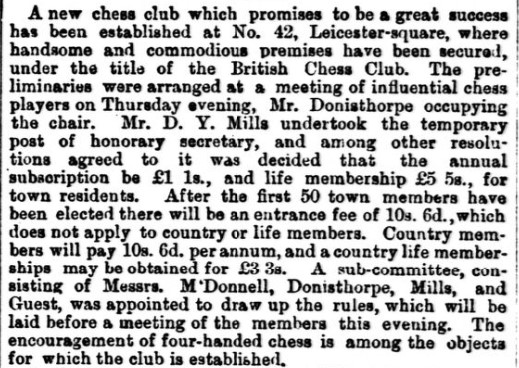

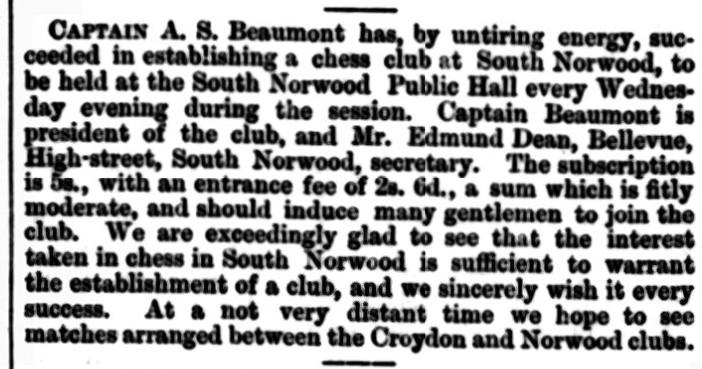

On the same day that this problem was published there was some important news.

A few months later the new club ran a master tournament in which Guest took part, but this time he was much less successful, only scoring 2/7, well behind Blackburne (6½), Bird and Gunsberg (both 5), and not helped by defaulting his game against Pollock.

I’m not sure whether or not this game was played in the tournament. Guest attempted to play like Steinitz, but it didn’t end well.

He had better luck later in the year in the British Chess Association Amateur Championship, which was won by Gattie (15/18), Guest sharing second place with previous Minor Piece subjects Hooke and Wainwright on 13½/18.

The eccentric Wordsworth Donisthorpe didn’t last long in this game.

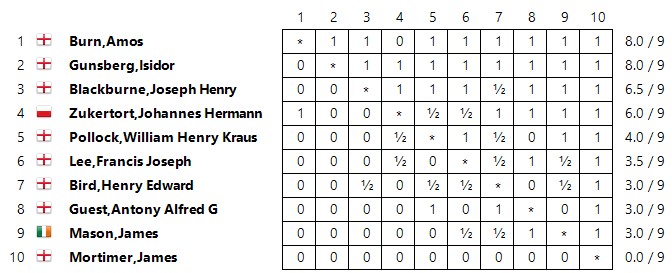

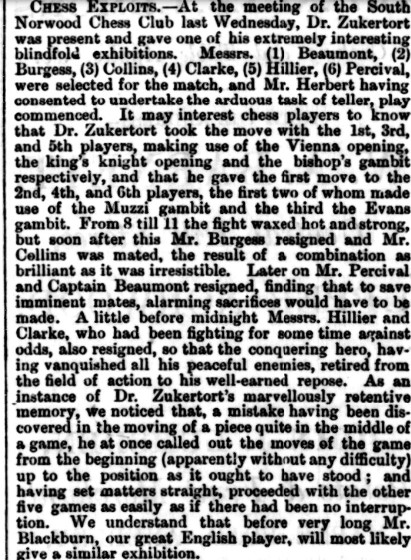

Guest’s next tournament was towards the end of 1887: the British Chess Association Congress in London. He had originally entered a lower section, but, on the withdrawal of Skipworth, was, at the last minute, promoted to the master section, where he would face the likes of Blackburne, Burn, Gunsberg and the ailing Zukertort.

He got off to a flying start, winning his first three games, against Bird, Pollock and the perpetual backmarker Mortimer.

His game against Pollock wasn’t short of excitement. He defended the Evans Gambit and, after various adventures, his extra pawn on the queenside eventually turned into a queen.

In Round 3 Guest sacrificed two rooks to win Mortimer’s queen. He miscalculated some later tactics, but his opponent failed to take advantage.

After a loss to Lee in the fourth round, his fifth round opponent, Mason, failed to arrive because he had confused the start time. Guest was originally awarded a win by default, but it was later decided that the game should be replayed, Mason winning.

He then lost his last four games against some of the world’s strongest players.

Against Burn he played a totally unsound Greek Gift sacrifice in this position, overlooking Black’s diagonal defence.

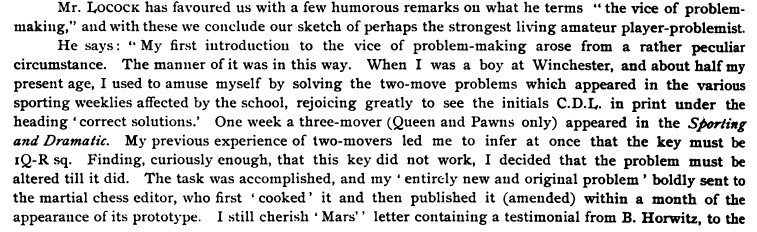

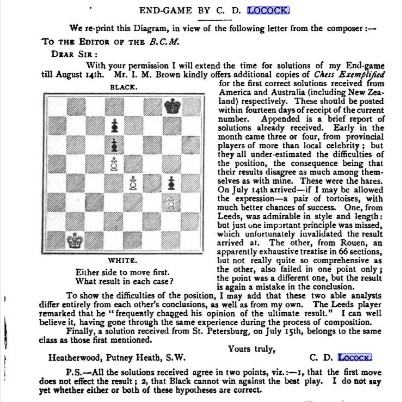

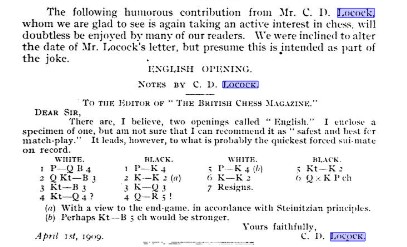

The game continued 9. Bxh7+? Kxh7 10. Ng5+ Kg8 and now he must have realised that 11. Qh5 fails to Bf5, while the move he tried, Qd3+, failed to g6. Regular Minor Piece readers will recall Locock making the same mistake.

Here’s the tournament crosstable.

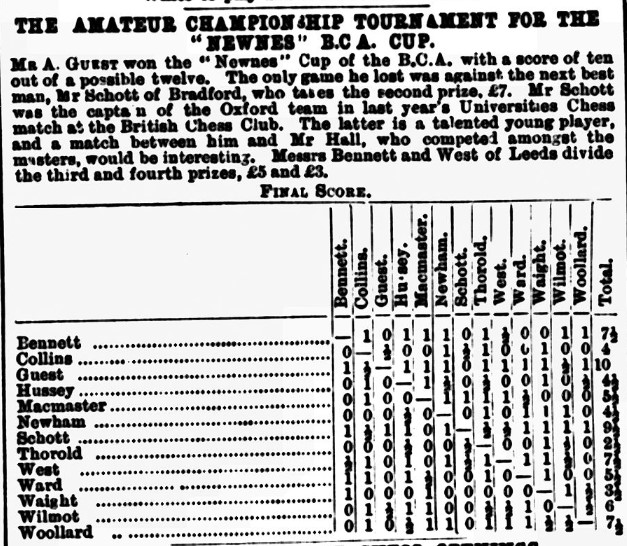

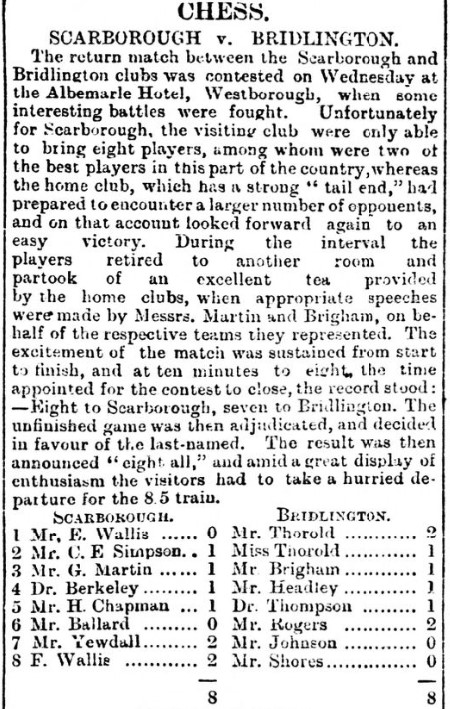

In August 1888 the British Chess Association Amateur Championship took place in Bradford. I’m not sure how ‘amateur’ was defined (Guest was a professional chess journalist, but not a professional player), but the 1888 event was a rather weak affair compared to other years, notable for the participation of Eliza Thorold in days when ladies very rarely competed against gentlemen. There was a master tournament taking place at the same time in which some of the stronger amateurs, such as Charles Dealtry Locock, participated. Guest won with a score of 10/12, just half a point ahead of 20-year-old Bradford born mathematician George Adolphus Schott, who, however, defeated him in their individual game.

In this game, winning his opponent’s IQP proved decisive.

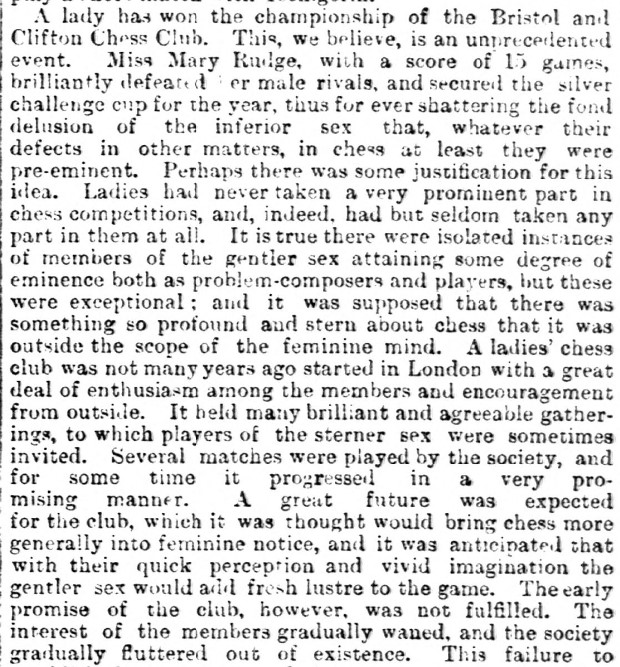

In August 1889 Antony Guest reported some important news. A lady had won the championship of the Bristol and Clifton Chess Club.

“There is no reason why (ladies) should not excel at the game.” Guest’s views, propounded in a Conservative-leaning newspaper, were quite enlightened for his day. It was not until 1895, though, that another – very successful – Ladies’ Chess Club was started.

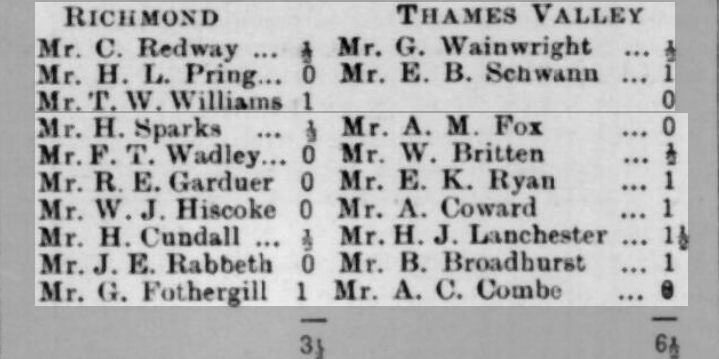

In November and December 1889 the British Chess Association Masters and Amateur tournaments took place consecutively rather than simultaneously in London, so George Wainwright was able to play in both events, while Guest only took part in the latter event. In those days games in amateur tournaments were played on a fairly casual basis with games often being postponed when one of the players was unavailable.

It seems that this event ground to a halt just before Christmas once Wainwright had guaranteed victory. Several of the other players, including Guest, had been too busy to play many of their games.

It’s not known whether any further games were played after this incomplete crosstable was published.

As you’ll see, Guest was the only player to beat Wainwright, in an opening variation still topical today.

He made a tactical oversight in his game against Thomas Gibbons. His opponent, a disciple of Bird, opened with 1. f4 and sacrificed a pawn on the kingside for nebulous attacking chances.

In this position, 25… Ne7 would have kept him well in control, but he erred by playing 25… Be7? 26. Rdg1! Qxh4? 27. Rxg7+ Kh8 28. Qxf5!!, after which he had to resign.

From here on, Antony Guest was playing less frequently, perhaps by choice, or perhaps because he was too busy with other activities.

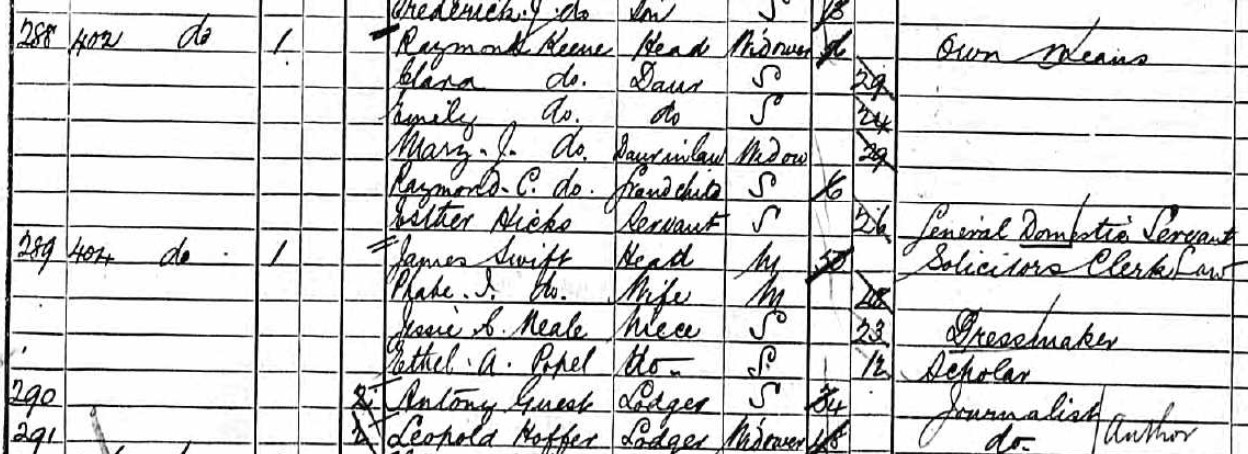

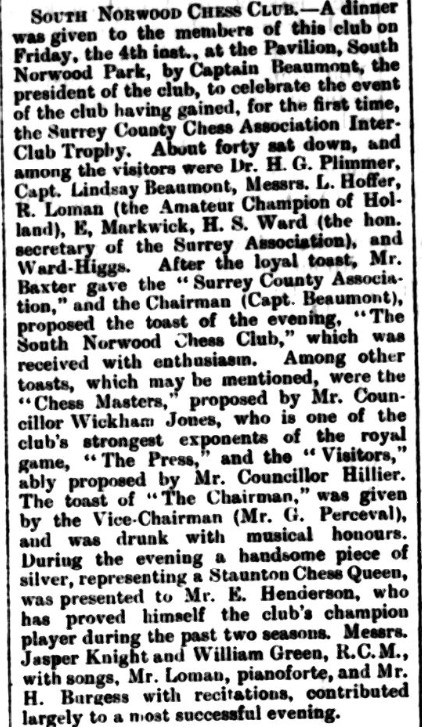

The 1891 census found Guest and his fellow chess journalist Leopold Hoffer living in lodgings in Fulham Road, right by Stamford Bridge stadium, which would, in 1905, become the home of the newly founded Chelsea FC.

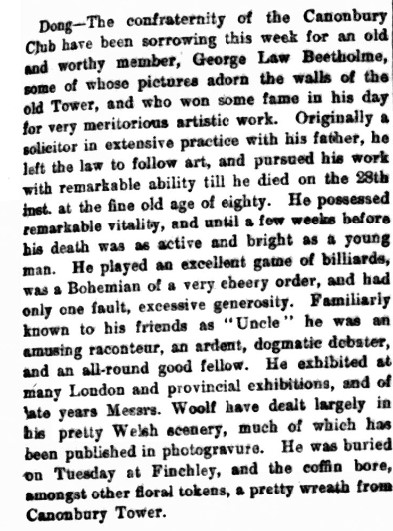

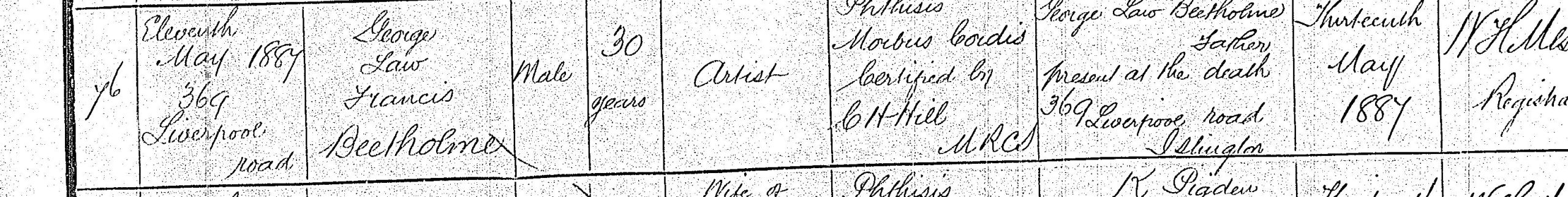

Just look at the name of their next door neighbour.

Yes, there he is: Raymond Keene. Not, to the best of my knowledge, related to his grandmaster and author namesake, although this Raymond’s son and grandson were also named Raymond Keene.

In an 1891 club match Guest’s temporary queen sacrifice brought victory against a strong opponent who really should have spared himself the last 20 moves.

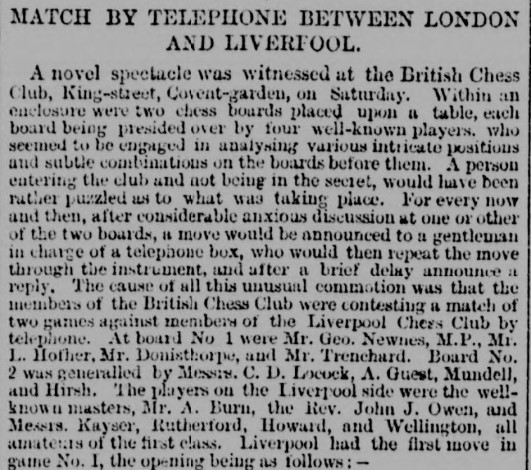

Later that year, Guest and Hoffer were both involved in a telephone chess match against Liverpool.

Liverpool won the first game, while the second game resulted in a draw.

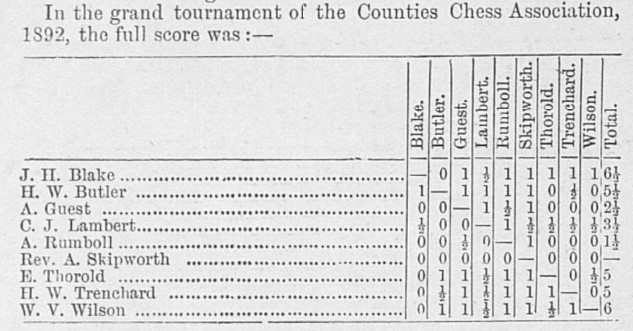

In August 1892 Guest returned to tournament chess, taking part in the Counties Chess Association tournament in Brighton.

It didn’t go well.

George MacDonnell was particularly scathing about his performance.

He should make due preparation and exert himself to the utmost. He didn’t pull his punches, did he?

Guest went horribly wrong on move 10 against the eventual winner.

But he did manage to win a nice minature against Lambert.

The following month he reached this position in a game at Simpson’s against OC Müller.

Here, Guest played 27. Qg6!, an offer which can’t be accepted, and threatening Qxh7+, an offer which can’t be refused. Black should now play 27… h6, when the game is likely to be drawn by perpetual check after 28. Rh3 and a later Rxh6+. Instead he erred with 27… Bg2?, and had to resign after 28. Rg4, as h6 would be met by Rxg2.

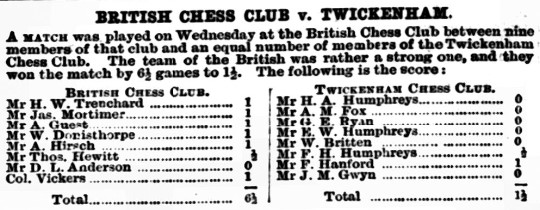

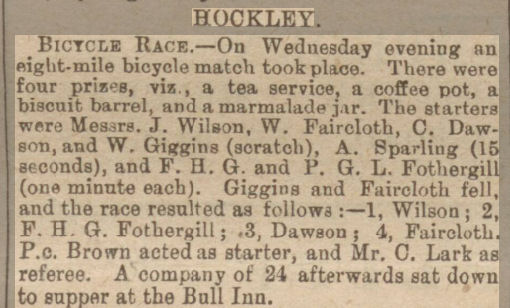

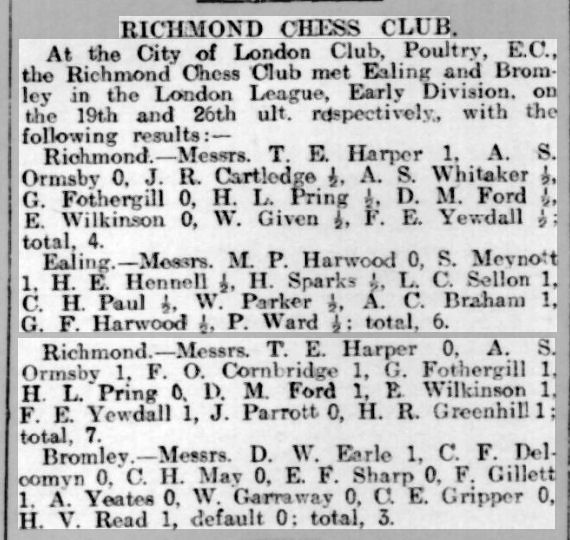

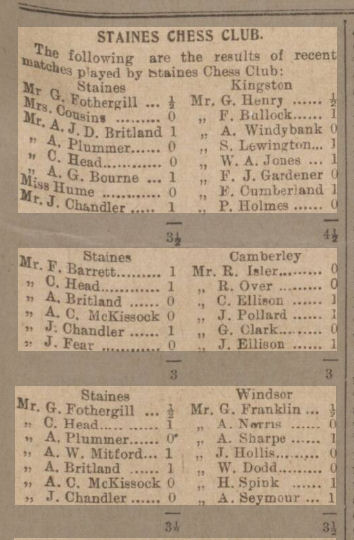

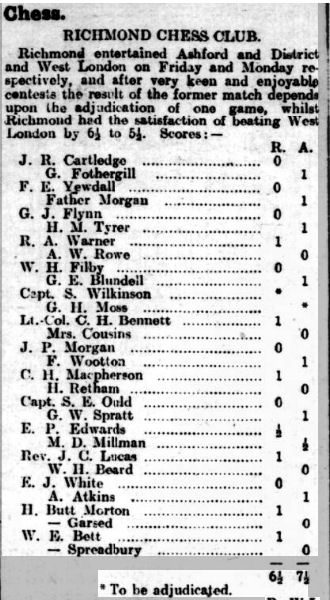

This scathing criticism of his play in Brighton didn’t stop him playing in club matches, such as this one against Twickenham.

You can read more about the Humphreys family here and about Guest’s opponent here.

He was also playing for Metropolitan, here losing a brilliancy against one of the ‘fighting reverends’. He really should have known his chess history, though. Wayte reached a winning position from the opening by transposing into a very well known predecessor.

By now Antony Guest had resumed his problem composing career, now without collaborators.

Problem 3. #3 A Guest Morning Post 1893

(Source given in MESON: however I wasn’t able to find it in a quick look to identify the date of publication.)

Problem 4. #3 A Guest Illustrated London News 25-08-1894

In 1895 he took part in the cable match between the British and Manhattan Chess Clubs, where he faced John ‘Paddy’ Ryan, capable, according to the press, of producing ‘startling brilliancies’.

Here, Ryan punted the speculative 21… Bxh3!?. What do you think? We’ll never find out what would have happened as at that point time was called and the game declared drawn.

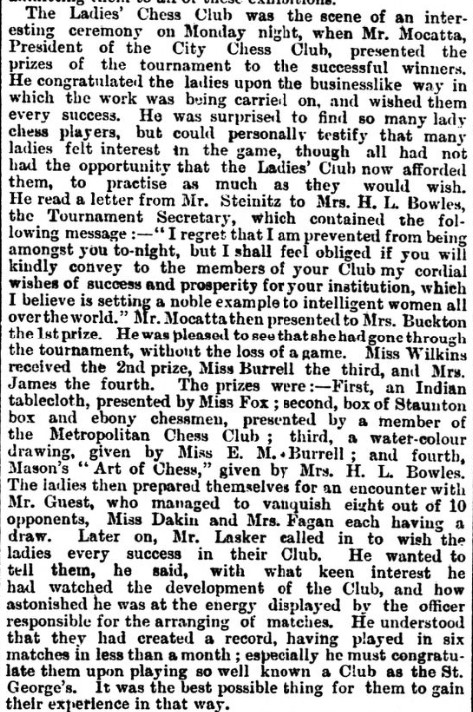

The Ladies’ Chess Club had been founded in January 1895, and Guest used his Morning Post column to promote their activities. He was invited to give a simul at their prizegiving ceremony.

Approaching his 40th birthday, it might have seemed like Antony Guest was a confirmed bachelor, but in 1896 he married Violet Harrington Wyman, some eleven years his junior. Violet’s brother Harrington Edward Hodson Wyman, was a knight odds player at the British Chess Club, later becoming vice-president of Ealing Chess Club. Her family firm were the publishers of Mortimer’s The Chess-Player’s Pocket Book.

In January 1897 Guest returned to tournament chess, playing in a ten-player selection tournament for that year’s Anglo-American cable match. Again he failed to complete the event, withdrawing after only three games, two losses and a win against Herbert Jacobs. Whether or not this was due solely to pressure of work is unclear.

This would be his last tournament, although he continued playing club chess. His performances, as you can see here (taken from EdoChess), show a steady downward trajectory after a promising start.

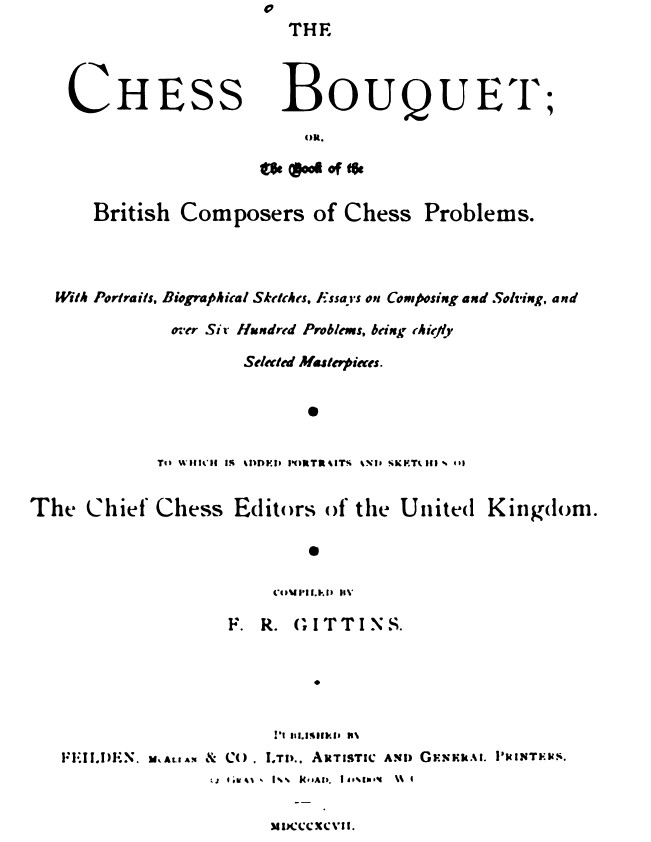

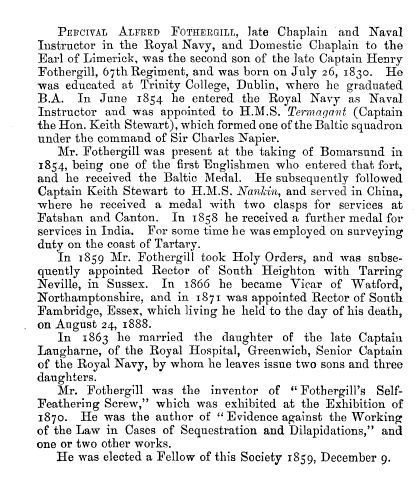

The year 1897 was significant for the publication of FR Gittins’ volume The Chess Bouquet.

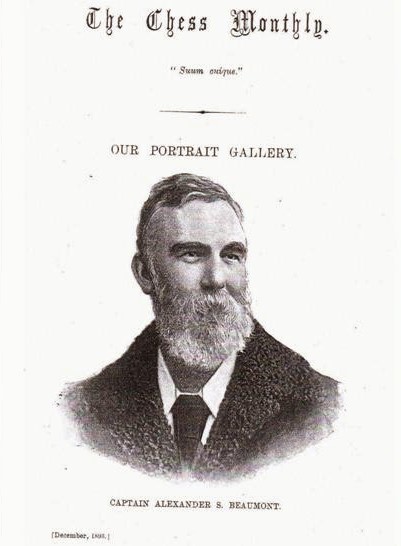

As one of the Chief Chess Editors of the United Kingdom, Guest certainly qualified for inclusion.

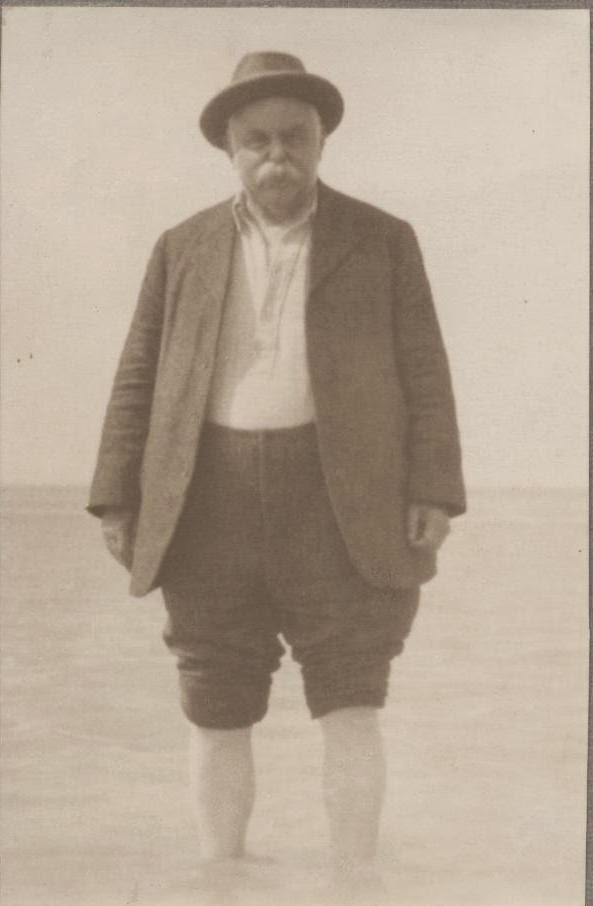

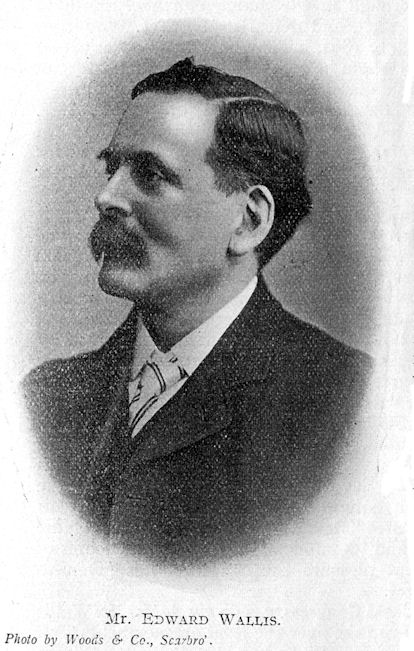

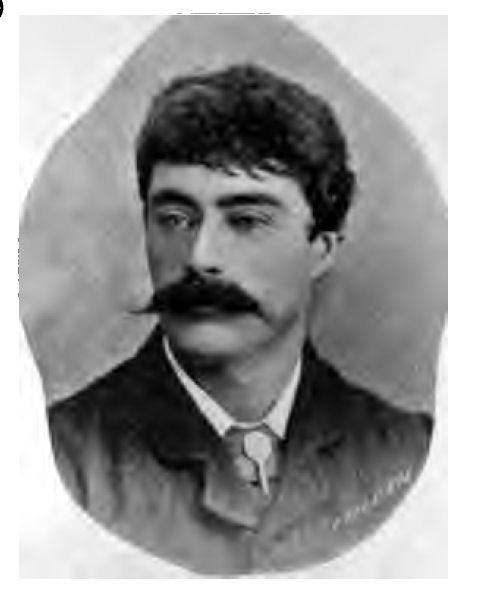

We’re offered a photograph, a biography, a game (against Pollock, see above) and two problems. Here’s how Gittins describes him.

Physically, Mr. Guest is a perfect giant, his towering form and splendid proportions being well in evidence at the recent Hastings Festival. Socially, he is one of the best, full of bonhomie and good humour.

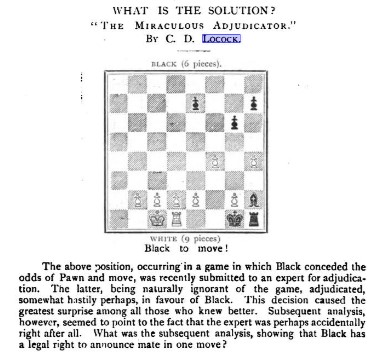

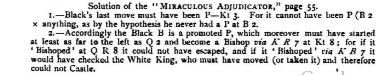

This is a charming mate in 2, which, unfortunately, had been anticipated by Conrad Bayer, who had published a mirror image back in 1865. It’s been reprinted on a number of occasions over the years.

Problem 5. #2 A Guest The Chess Bouquet 1897

The second problem, number 3 above, was unfortunately given with a missing pawn on c7, allowing an unwanted second solution.

He wasn’t the only Guest in The Chess Bouquet. There were also entries for Black Country problemists Thomas Guest and his son Francis Hubert Guest, who were not, as far as I can tell, related to Antony.

Here’s an exciting game played at Simpson’s against a French opponent.

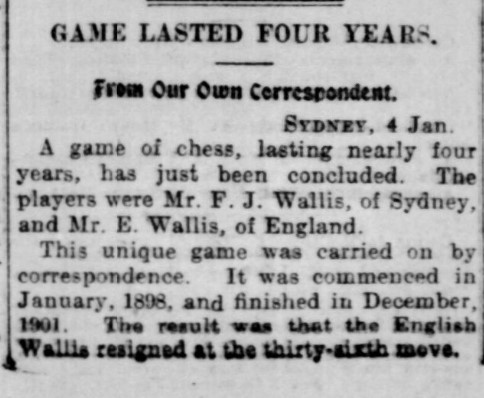

Although now retired from tournament play, Guest was still making occasional appearances in consultation games, and club and county matches, both over the board and by correspondence. He was also publishing the occasional problem, such as this one, from 1900.

Problem 6. #3 A Guest Morning Post 12-03-1900

Later that year, Guest wrote a very interesting article entitled Steinitz and Other Chess-Players, first published in The Contemporary Review, and later republished in the USA in The Living Age.

The last three paragraphs, which take a broader social view of the game, are those which interest me most.

Here he is, celebrating the increasing popularity of chess among the working classes.

The present extraordinary growth of the popularity of the game must surely have some significance. Many of the players are young men engaged in offices, shops and factories; that their numbers include several clergymen, doctors, lawyers and members of other professions is not so remarkable. What strikes me as important is that so many young clerks, and others of similar occupation, should find their chief recreation, at least in the winter months, in the game of chess.

And here again on the artistic side of chess.

But I believe that in most of us there is some kind of artistic instinct, some aesthetic tendency, that finds no outlet in the humdrum of everyday life. If this is true it would sufficiently account for the increasing popularity of chess, for it is an art as well as a game. Its intricacies and combinations are capable of affording aesthetic delight that may be compared with the emotions produced by poetry, pictures or music — different, no doubt, but, to many, similarly sufficing. One need not be an expert to enjoy the pleasure of play; to the beginner it is like a voyage through an unknown country teeming with beautiful surprises. Every sitting reveals some new and captivating feature, suggests some tempting path, or affords some hint as to the best mode of pursuing the journey.

They don’t write them like that any more, do they?

You can read the whole article, along with the chapter about Guest in The Chess Bouquet, in this excellent article by Batgirl (Sarah Beth Cohen).

In 1901 it was time for another census. Strangely, Mr & Mrs Guest were not together. Antony was lodging in Bayswater, while Violet and her parents were lodging in Hastings, perhaps on holiday together.

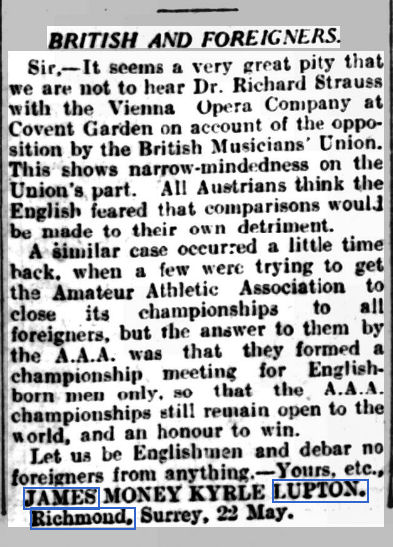

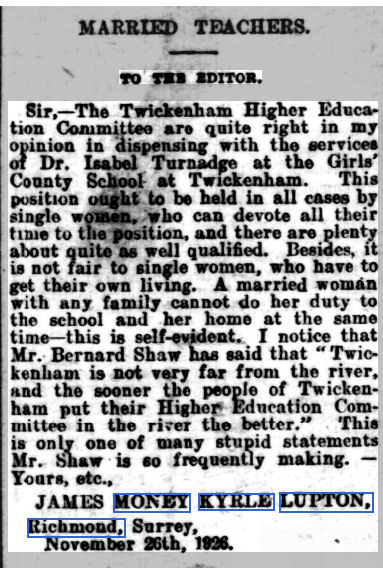

He returned to the social aspect of chess in a 1901 article explaining how chess can build friendships between people of different nationalities.

For a few years now, Guest seemed, apart from his column, to stop both playing and composing, only resuming in 1907.

In this game against G Freeman from a Surrey v Essex county match he built up a strong attack from the King’s Gambit Declined.

Black had just blundered and now the rather neat 23. Rf5! forced resignation.

Problem 7. #3 A Guest Morning Post 12-08-1907

His game annotations were also being syndicated across various newspapers.

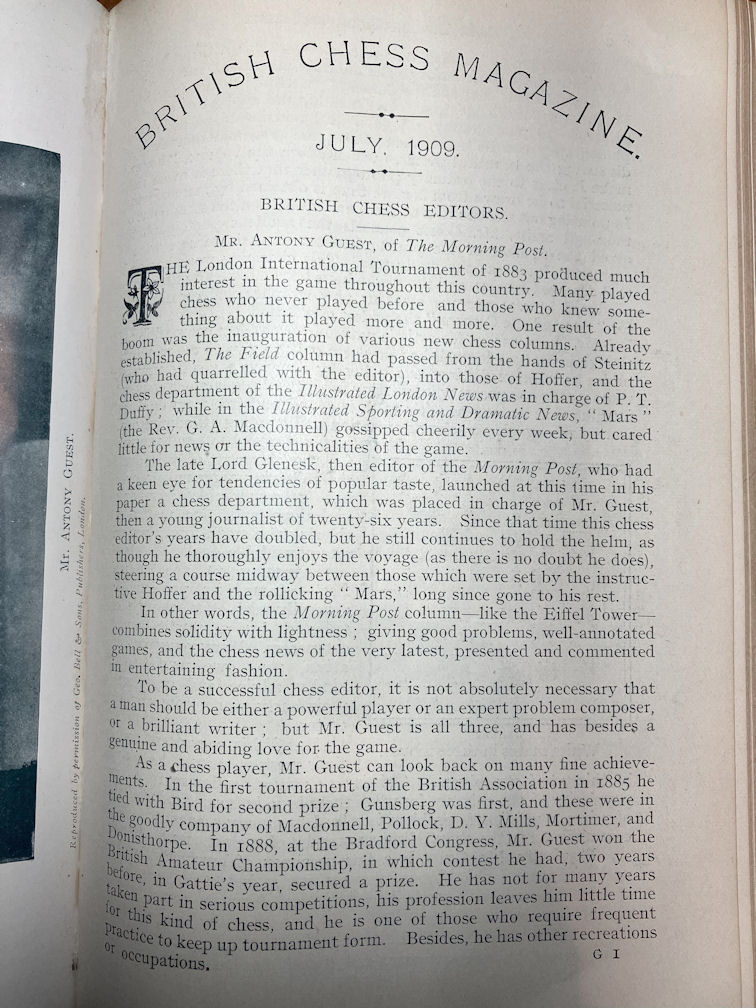

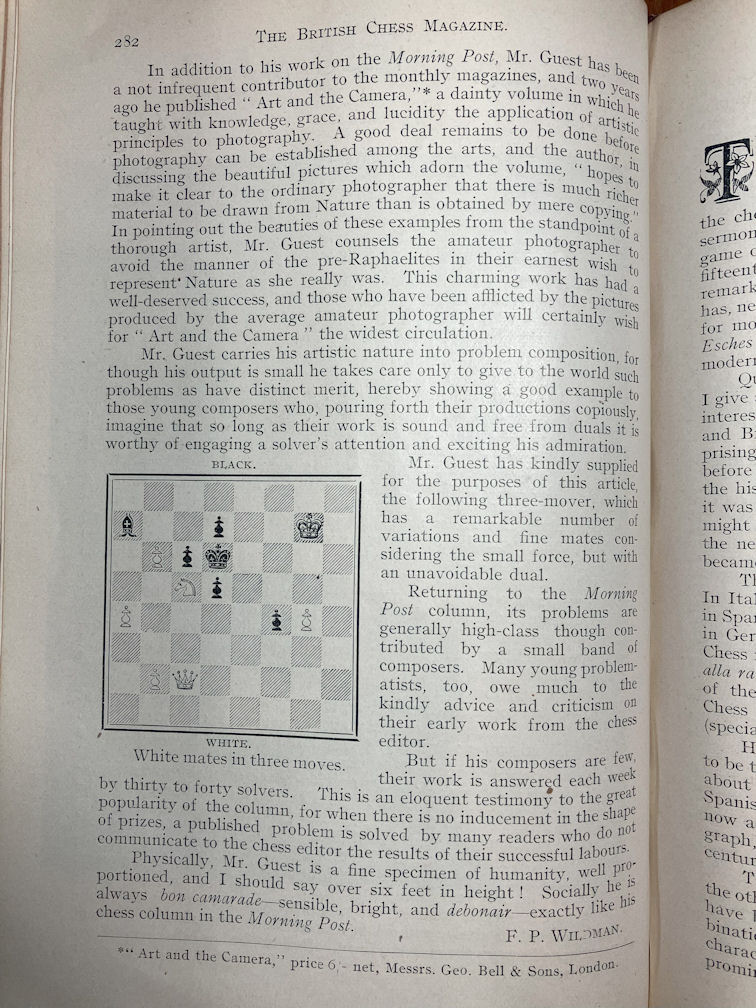

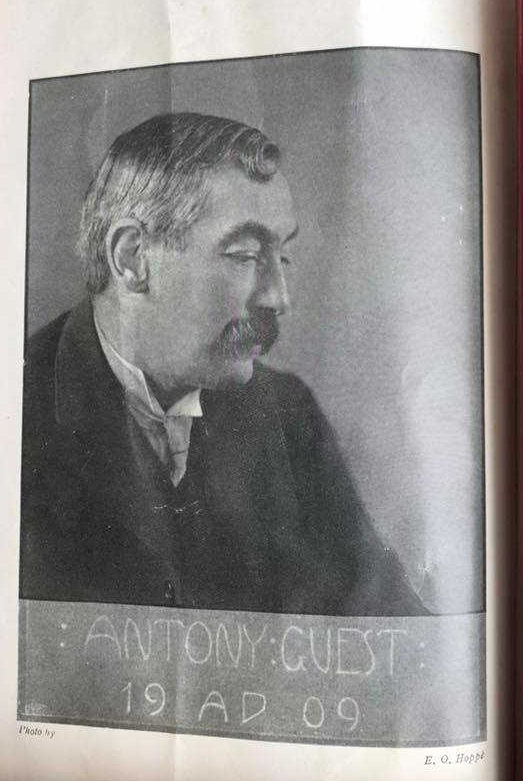

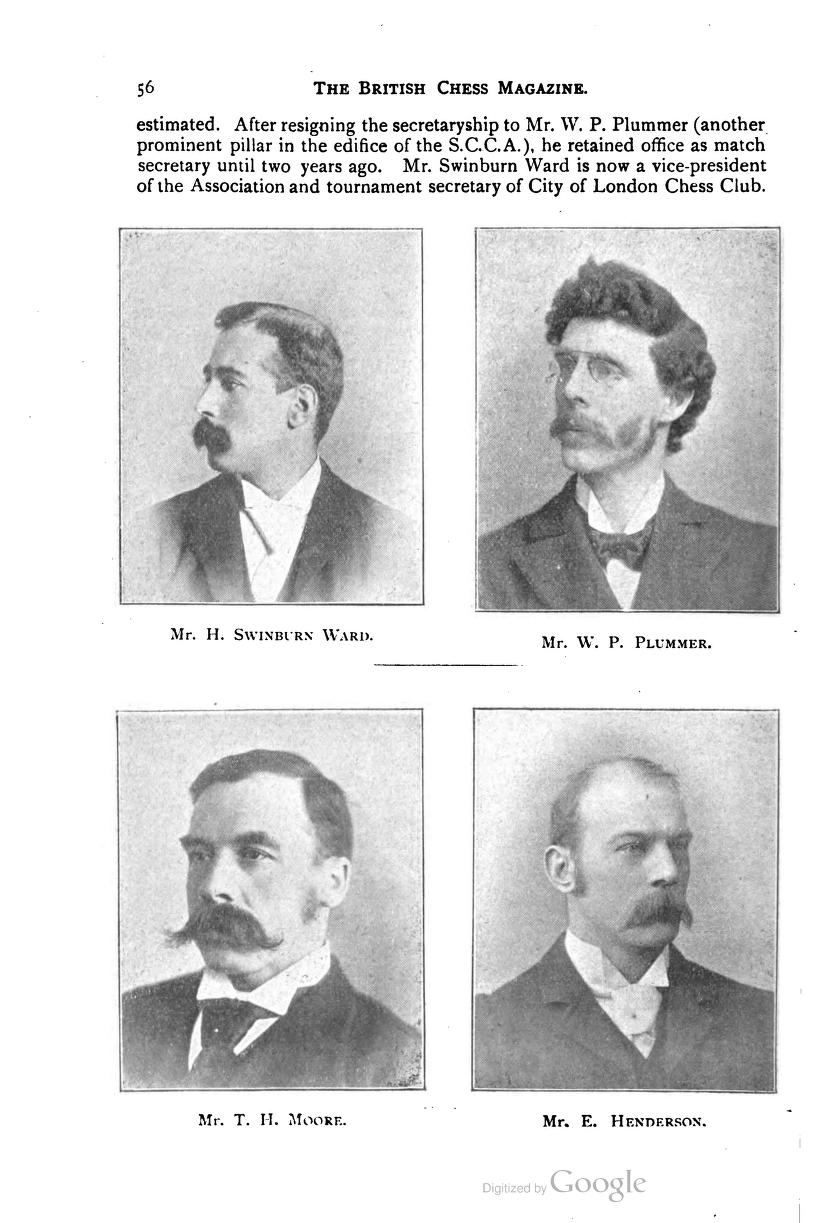

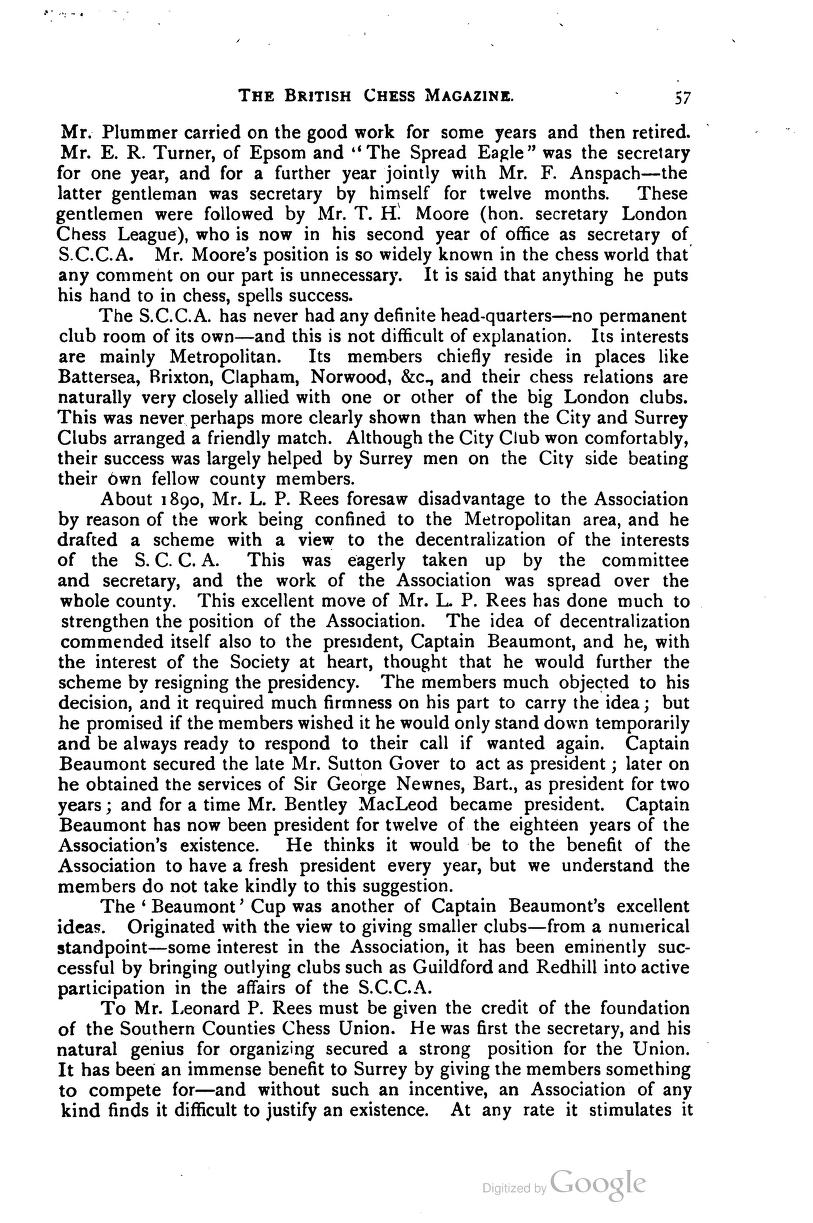

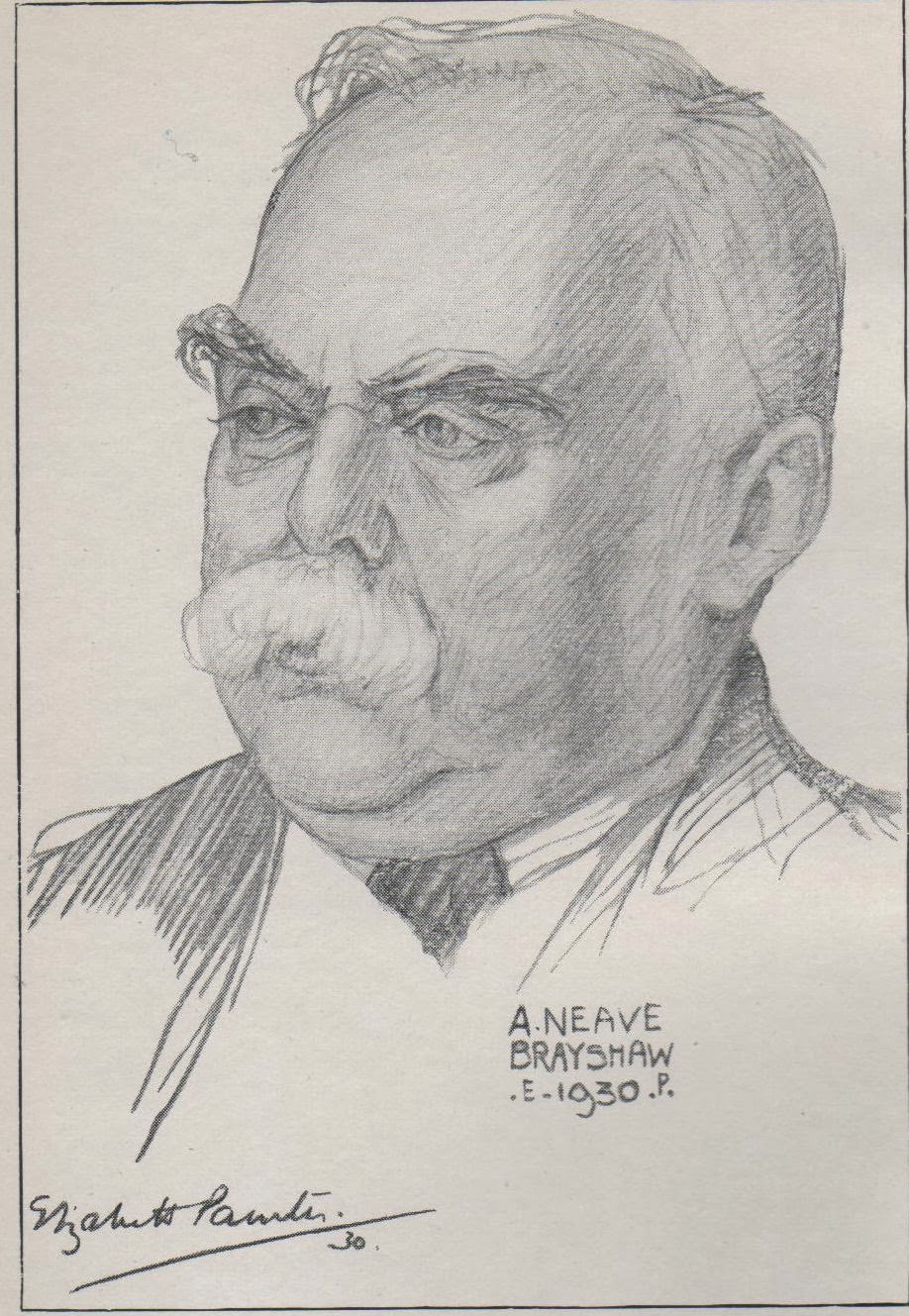

In July 1909 Antony Guest was honoured to be the subject of a feature in the British Chess Magazine, who published a photograph along with a biographical sketch contributed by Frank Preston Wildman.

Problem 8. #3 A Guest British Chess Magazine 07-1907

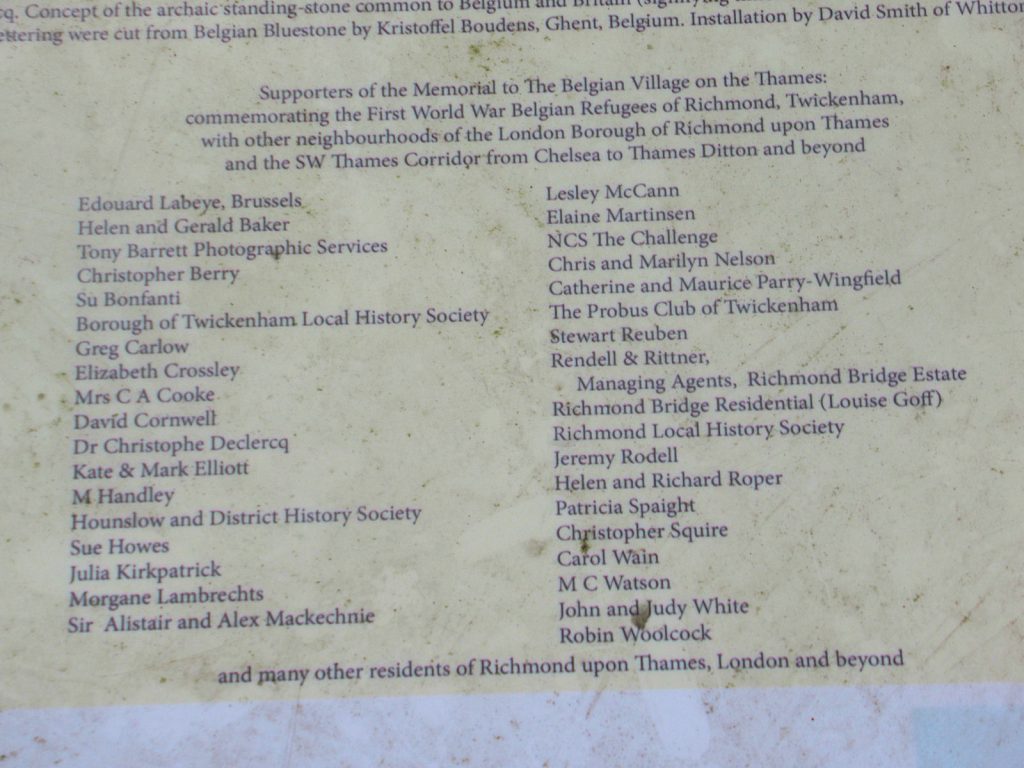

Here’s another photo from the same year taken by Emil Otto Hoppé (Wiki), who remarkably lived on until 1972. One of his publishers was Sampson Low, Marston & Co, founded by an ancestor and namesake of the current Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club Secretary.

At some point during this decade, Antony and Violet moved out to 1 Anglesea Road, Kingston, alongside the Thames half way between Kingston and Surbiton. This was a sizeable property, with 12 rooms excluding bathrooms. (I’m not sure whether or not it was the white building you can see behind the trees, which is now Anglesea Lodge, 28 Portsmouth Road.)

This is the view from the Barge Walk on the other side of the river.

The 1911 census found them there, along with two servants, William and Marie Wilkins, a married couple of about their age, and the Wilkins’ teenage daughter Elsie.

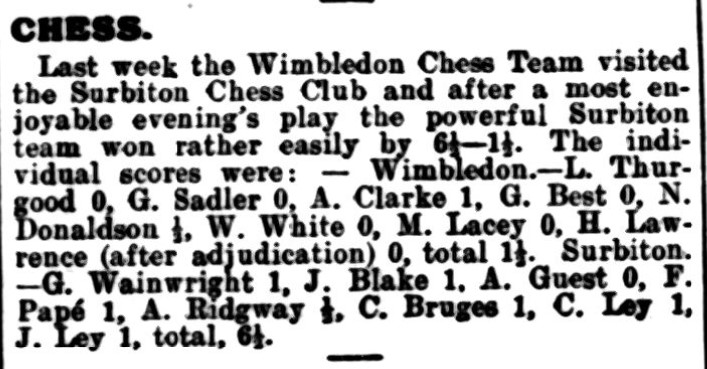

Guest decided to join Surbiton Chess Club, playing in this match against Wimbledon.

He was now becoming less active in the chess world, but in 1914 had the opportunity to express his views again on chess for schoolboys.

“In opening the way to friendships the practice of chess is very valuable to young men.”

I totally agree, although these days we might want to refer to young people instead. It worked for me, anyway.

Guest’s column continued through the war, although there was little chess action to report.

Here, he took the lack of competitive chess during the hostilities to promote the value of social chess in promoting friendship.

His wife Violet sadly died in February 1921. That June the 1921 census found him still the head of the household at 1 Anglesea Road, and still working as a journalist. There was a resident housekeeper, but most of the property was taken up by motor builder John Bambury, who ran his own business in Kingston, along with his wife and five children aged between 17 and 22.

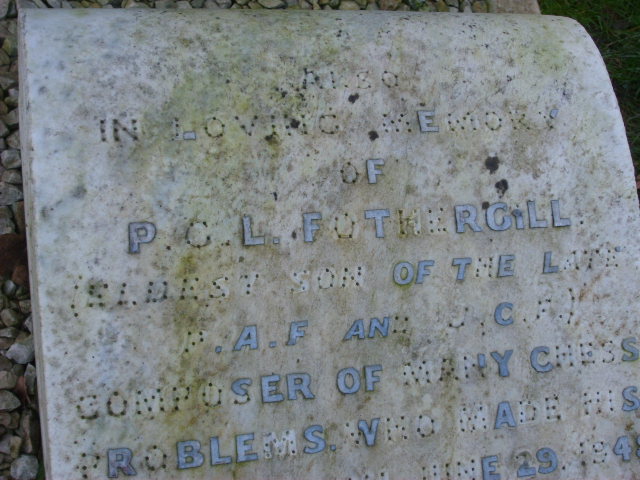

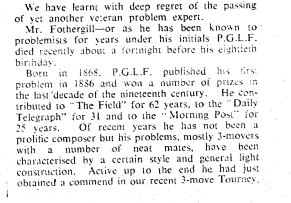

Guest was still seen regularly at major events such as Hastings and the British Championship, but by the 1924-25 Hastings Congress he was clearly in poor health and died after an operation on 29 January.

He didn’t leave that much money, compared to Hamilton Brooke Guernsey, one of whose administrators, Leslie Dewing, – one for coincidence lovers here – would have seen him at Hastings four weeks earlier, where he lost all his games in the Premier Section 1. (Coincidentally again, or perhaps not, there’s currently a marketing agency in Guernsey called Hamilton Brooke.)

The Morning Post was far from being Guest’s only chess outlet. At various times, according to Tim Harding in British Chess Literature to 1914, he also wrote columns for the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, the Daily News, Cassell’s Saturday Journal, Life and Tinsley’s Magazine.

Nor was chess the only subject on which he wrote. In 1891 Guest and barrister Sylvain Mayer co-authored Captured in Court, a novel with a legal setting. Some of the reviews were pretty harsh. “It is very unlikely to add to the reputation of either as story writers”, according to the Glasgow Herald. “… the bundle of incidents which does duty for a plot is as amateurish as the style”, proclaimed the National Observer. According to the Weekly Dispatch, “The plot is preposterous and the dialogue inane”. Preposterous plots and inane dialogues were perhaps more suitable for children’s literature, and, from 1895 onwards, he contributed to collections of short stories alongside such authors as E(dith) Nesbit, still much loved and remembered today for books such as The Railway Children.

In 1896 Antony Guest contributed an article on Some Old English Games to The Badminton Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, describing games such as Pall Mall and Shuffleboard, illustrated by Albert Ludovici., followed by More Notes on Old English Games a year later, this time including Bandy-Ball and Nine Men’s Morris.

In the early 20th century he developed (pun not intended) an interest in photography, and in 1907 his book Art and the Camera was published by G Bell and Sons, who of course also published chess books.

This time the critics were unanimous in their praise. Modern reprints are readily available should you wish to read it.

In 1910 he turned his attention from cameras to cancer.

It’s still a hot topic today, and the evidence is still inconclusive.

A man of many interests, as well as chess, then. Polymaths were probably more common then than now.

There are a couple of family issues to clear up.

Antony and Violet had no children. His sister (Isabella) Katherine married a wealthy man named Robert Edward McLeod in 1883. Robert’s brother Bentley was a chess player, representing Surrey, Brixton and Metropolitan, through the last of which he would have known Antony. Robert died in 1893, leaving his wife with two young children. Neither of them had children, so that was the end of Augustus Guest’s family. Katherine died, like her father, in a mental hospital, in Brighton in 1941.

To find Antony’s closest relations, then, we have to travel to Australia. Henry, whom you met at the start of this article, returned to England with some of his many children after his retirement. The family was hit by tragedy when his daughter Helen died in 1907. Helen and her older sister Ethel were very close, and, 18 months later, Ethel, suffering from depression as a result of the loss of her beloved sister, took her own life. There were mental health problems, then, on both sides of the Guest family.

Henry’s son Stanley later returned to Australia, married and had six children, the youngest of whom, Marisa, born in 1929, is still alive. Marisa, the closest surviving relation of Antony Guest, is the mother of Ralph Jackson.

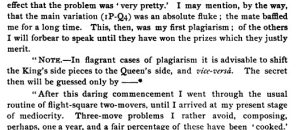

One of the wonderful things about chess is that, even if playing competitive chess doesn’t appeal to you, there are many other ways of living your life through your favourite game. For Guest’s contemporary and acquaintance Charles Dealtry Locock it was through problems, writing and, in the last period of his life, teaching. For Antony Guest himself, it was as a journalist and occasional problemist. His record of almost 42 years might pale in comparison with Leonard Barden’s records, but it’s still very impressive. You can see a lot in common: both strong players who, finding competition a little bit too stressful, concentrated on their, in both cases, excellent newspaper columns, and perhaps did far more good in promoting chess in that way than they would have done by just playing.

He was in many ways a man ahead of his time as well. Although he wrote for a conservative newspaper, he was always very keen to promote chess for ladies, for the lower middle and working classes, and for schoolboys (it would be left to Locock to include schoolgirls). He also promoted chess for recreational and social reasons, to establish friendships on a local, national and international basis. I couldn’t agree more. Ralph Jackson is very lucky to be able to count Antony Guest as a close relation.

Problem Solutions:

Problem 1:

Problem 2:

Problem 3:

Problem 4:

Problem 5.

Problem 6.

Problem 7.

Problem 8.

Acknowledgements and sources.

Ralph Jackson – private correspondence

Batgirl (Sarah Beth Cohen) articles on Guest and Donisthorpe at chess.com

Krone Family website here

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

ChessBase/MegaBase2023/Stockfish16.1

chessgames.com (Antony Guest here)

EdoChess (Antony Guest here)

British Chess Literature to 1914 (Tim Harding)

The Chess Bouquet (FR Gittins)

British Chess Magazine July 1909 (thanks to John Upham)

Wikipedia

Yet Another Chess Problem Database

MESON Chess Problem Database

Other sources referred and linked in the text.

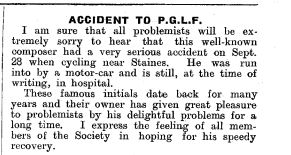

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

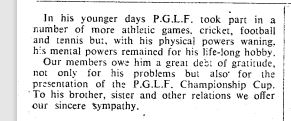

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.