From the back cover:

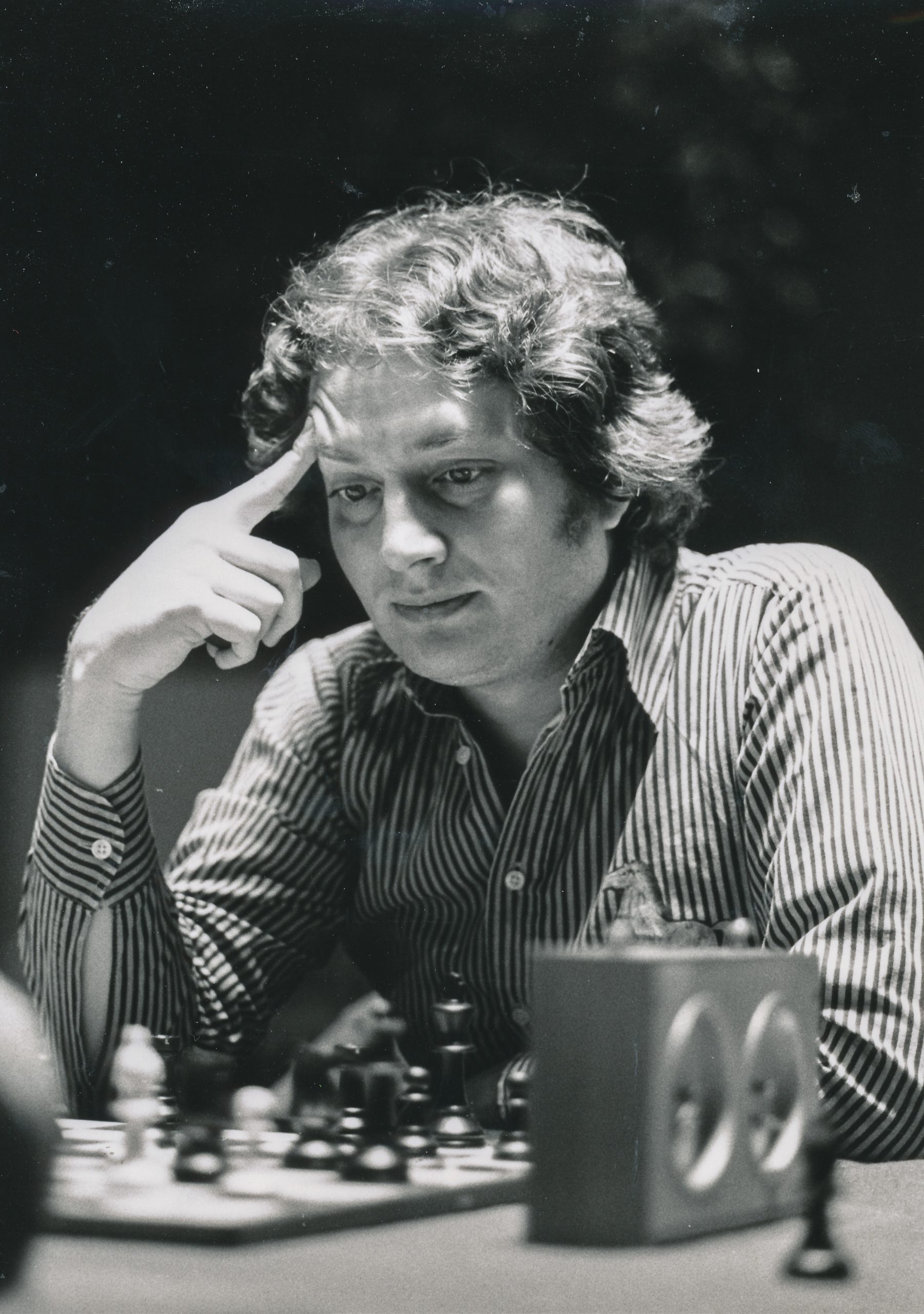

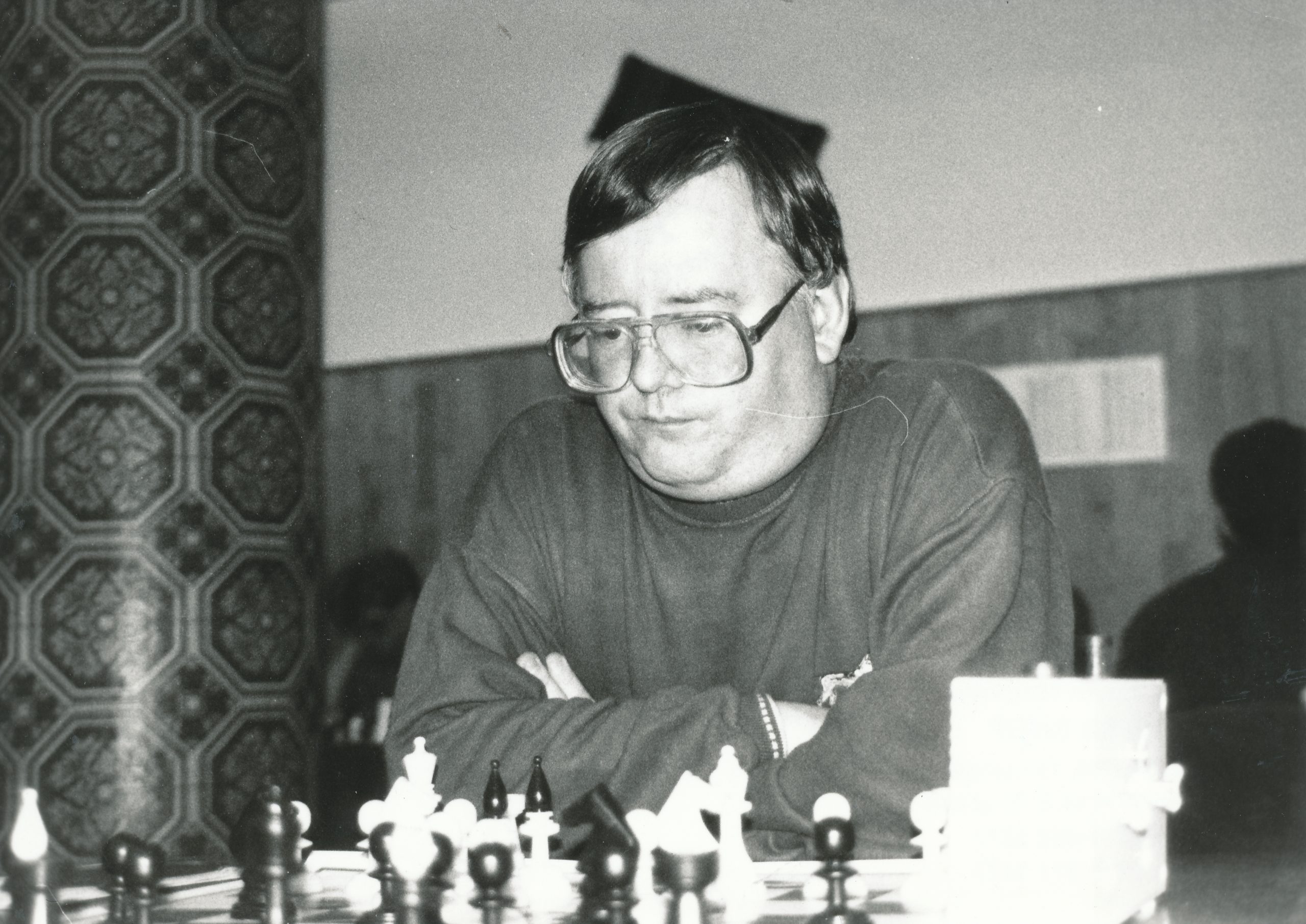

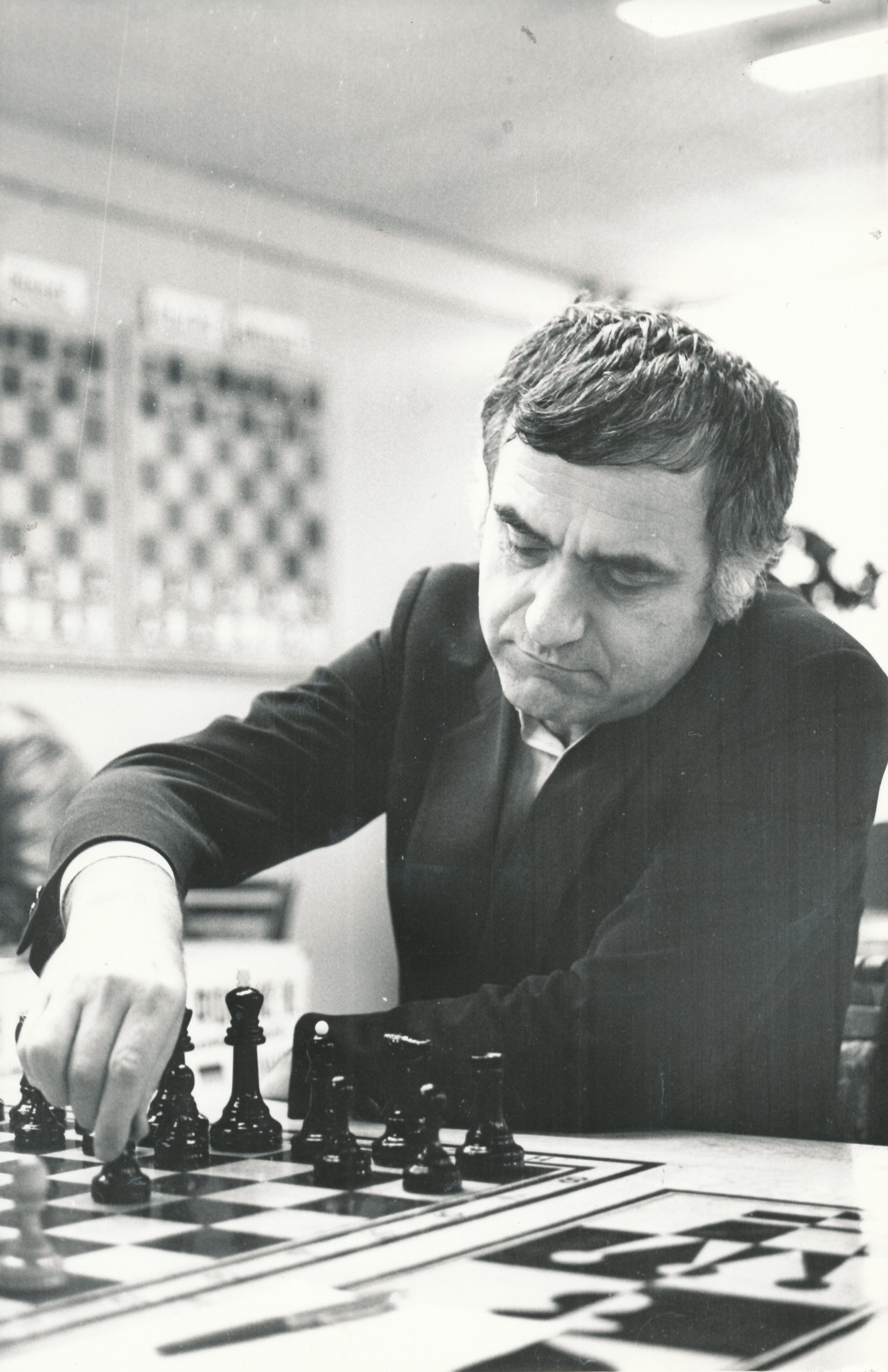

“Sergei Tiviakov was unbeaten for a consecutive 110 professional chess games as a grandmaster, a record that has only been broken by World Champion Magnus Carlsen. Who better to teach you rock-solid chess strategy than Tiviakov. He was born in Russia and trained in the famous Russian chess school. In his first book, he explains everything he knows about the fundament of chess strategy: pawn structures.

If chess players trust that their knowledge of opening theory and tactics is enough to survive in tournament play, they are mistaken. Once you settle down for your game and the first moves have been played, you will need a deeper understanding of the middlegame. And one of the most challenging questions is: how to navigate different pawn structures?

Sergei Tiviakov gives you all the answers in this first volume of his highly instructive series on chess strategy. ‘Tivi’ is famous for his deep chess knowledge and rock-solid positional play. He has gathered a rich collection of strategic lessons he has been teaching worldwide, drawing mainly from his personal experience. The examples and exercises will improve your chess significantly and are suitable for any reader from club player to grandmaster level.”

About the Author:

“Sergei Tiviakov is a grandmaster, winner of an Olympic Gold Medal, three times Dutch Champion, and European Champion. Yulia Gökbulut is a Women’s FIDE Master, chess author and sports writer from Turkey.”

Before we start, you might liked to inspect sample pages

This book has its origins in a recent series of lectures given by Tiviakov. His co-author was responsible for shaping the material into a book.

We start with a long introduction about the difference between human and computer chess, which is interesting in itself, but not directly relevant to the subject of the remainder of the book.

What you don’t get is a complete guide to pawn structures: if you want that you’ll need to look elsewhere. Instead, you get something very much based on Tiviakov’s own repertoire. In general you’d expect positional players to prefer queen’s pawn openings, just as Tivi’s hero Tigran Petrosian did, while tactical players will be more likely to choose king’s pawn openings. Tiviakov, though, has been almost exclusively a 1. e4 player throughout his career. With White he makes little attempt to secure an advantage, just aiming to reach a pawn formation he understands better than his opponent.

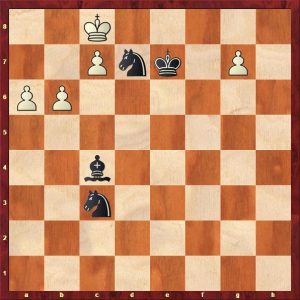

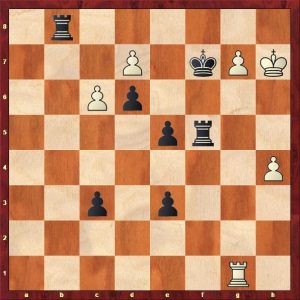

In the first chapter we look at positions with a pawn majority on one flank. Something like this formation, which Tiviakov often reaches after 1. e4 c5 2. c3, or 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nd2 c5 4. exd5 Qxd5.

He comments that he’s unaware of any book dealing specifically with this sort of position, and neither am I. If you’re likely to reach this sort of pawn formation in your games you’ll find this material very helpful and instructive.

In this position, from a game Tiviakov – Romanov (White to play), he discusses the idea of deciding, even this early in the game, which pieces you want to trade off for the ending. His conclusion is that ideally you should retain the dark squared bishops, so that you can attack Black’s queenside pawns, and try to trade everything else off. He managed to realise his plan successfully in this game, where he compared his style to that of Petrosian, Karpov and Carlsen.

I’ve thought for many years that perhaps the topic which, more than anything else, needed a book was that of doubled pawns. Naturally, I was delighted to see that Tiviakov devotes two chapters to this. Some of the examples were an eye-opener for me.

Here, he uses his game against Igor Efimov (Imperia 1993: it’s not in MegaBase) to demonstrate how he plays against the Trompowsky.

At first glance you might think that Black’s bishop on e6 looks like a rather useless Big Pawn, but Tiviakov explains that it’s actually more useful than its white counterpart.

But it’s important to understand that in chess a piece is labelled ‘bad’ or ‘good’ not by how it stands, whether it is blocked by pawns or not, but on its role in the actions that its army will carry out.

He explains that Black plans to swing his knight to e4, followed by b6 and c5, and, if White does nothing, by c4, b5, b4, Qd6 and Rb8.

A very instructive game, he claims, but you’ll have to buy the book to find out why.

It’s grandmasterly insights such as this, sprinkled liberally throughout, which make this book worthwhile.

Here’s another example. Tiviakov used to favour the Scotch against 1… e5, but dropped it after a loss against Mamedyarov in 2006.

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4 exd4 4. Nxd4 Bc5 5. Nxc6 Qf6 6. Qd2 dxc6 7. Nc2 Bd4 (obligatory to prevent Qf4 according to Tivi) 8. Bc4 Be6! 9. Bxe6 fxe6

Black has gone in for a deterioration of his pawn structure. From the viewpoint of classical chess strategy, he should stand worse, because of the doubled pawns, the isolated pawn on e6 and in general the three ‘islands’ against two for White. But in concrete dynamic play, Black is not worse. This is something you should understand.

We now move on to positions with semi-open files in the centre.

This sort of pawn formation can arise from very many openings, for example the Caro-Kann or Tiviakov’s favourite Scandinavian.

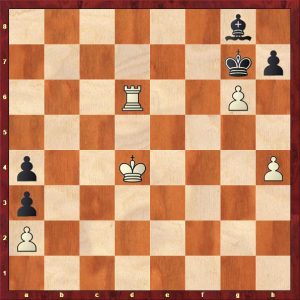

Here’s another instructive example, with White to play in the 2006 game Godena – Tiviakov. A Qd6 Scandi has resulted in an equal position. Now White chose the apparently natural (to me anyway) 22. c4.

It is possible to place the pawns side by side on c4 and d4, if White has definite dynamic prospects or if the opponent cannot organize an attack on them. In this concrete example, I can prevent the pawn advancing to d5 and organize an attack on it.

After White’s 32nd move this position was reached. Objectively it’s completely equal, but in practice it’s Black who’s pressing.

Tiviakov again:

After the exchange of rooks, the queen and knight are stronger than the queen and bishop team, because Black has certain secure squares available to him. For example, the queen can come to d4 and then manoeuvre such that he can switch the attack between the white king, the queenside pawns and the pawn on f2.

White’s position is very unpleasant.

Another insight into how a strong grandmaster will perceive a position which a club player like me would think of as just being equal.

The next chapter is about positions with seven pawns each and an open d or e-file.

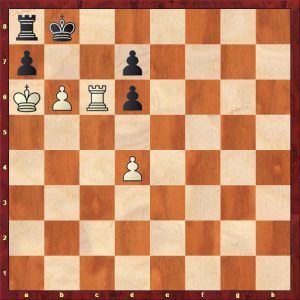

In this position from a Tiviakov – Kasimdzhanov game, we can deduce from a piece comparison that White stands slightly better. His dark squared bishop is clearly superior, especially after a future f3 and Bf2. It’s perhaps less immediately obvious that his light squared bishop is also better than its opposite number as it’s looking at Black’s slightly vulnerable queenside, while the bishop on b7, once White’s played f3, will be ineffective. Furthermore, White has a potential square on d5, while Black doesn’t have an equivalent square on d4.

Moving on again, we have, logically enough, Two Open Files in the Centre.

Here’s a position from Tiviakov – Ibrahim (2015), with White to play.

If I had a position like this I’d be thinking about offering a draw and heading to the bar, but in fact White is much better here. Black already has a weakness on d5, and by playing Bg4+ now (as it happens Stockfish thinks the immediate Re1 is preferable) and provoking f5, he creates additional weaknesses on e5 and e6.

The final chapter is rather different, looking at the way Tiviakov defends against flank openings, using a double fianchetto system. Again, interesting, but it doesn’t quite fit in.

Summing up, we have four chapters, 1, 4, 5 and 6, which fit together logically, and three chapters, 2, 3 and 7, which, although equally instructive and interesting, don’t really fit in, as well as a long introductory chapter of only tangential relevance. Although it might not make a coherent whole, the quality of the material is very high.

However, contrary to Tiviakov’s claim in his preface that the book is aimed at players of all strengths, from beginner to Grandmaster, it really isn’t. At lower levels games are usually decided by tactical oversights rather than subtle positional advantages of the type we see in this book. I’d say it was suitable for players of, say, 1750 upwards. Again, if you favour kingside attacks, sharp tactics or heavy opening theory this might not be the book for you. But if you’re a strong player with a preference for positional chess, and especially if you share some of his opening choices, this is a book you really don’t want to miss. A second volume has now been published, which I look forward to reading in due course.

Production values are well up to this publisher’s usual high standards, even though a final read through by a native English speaker might have helped. As usual with books for New in Chess, active learning is encouraged: the reader is asked questions every few moves.

Perhaps this isn’t a book for everyone, but the content is excellent throughout, and, if you’re strong enough to appreciate grandmaster level positional concepts, the book can be highly recommended.

Richard James, Twickenham 12th August 2024

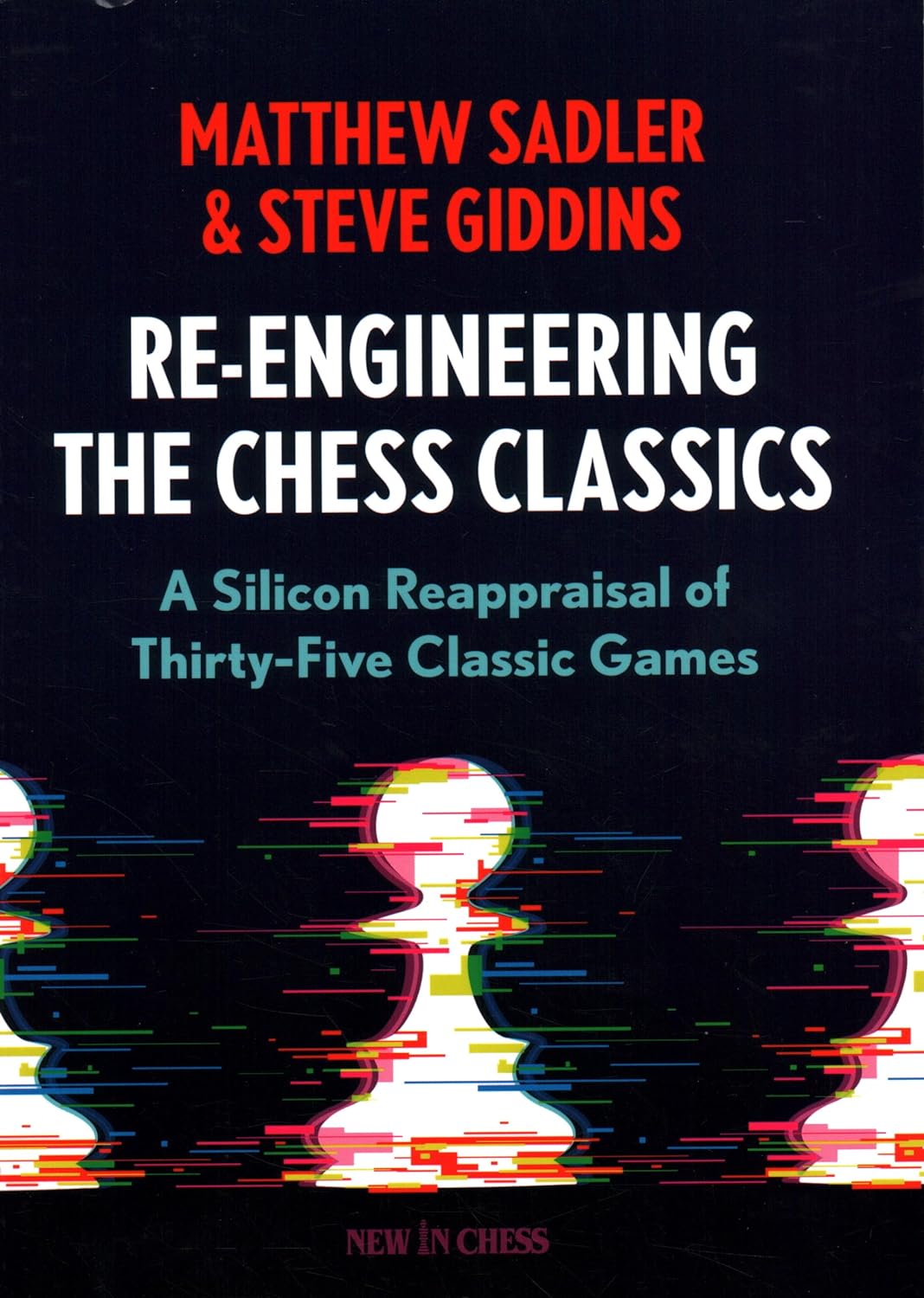

Book Details:

- Softcover: 264 pages

- Publisher: New In Chess; 1st edition (31 Jan. 2023)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9493257851

- ISBN-13:978-9493257856

- Product Dimensions: 17.22 x 1.65 x 23.01 cm

Official web site of New in Chess.