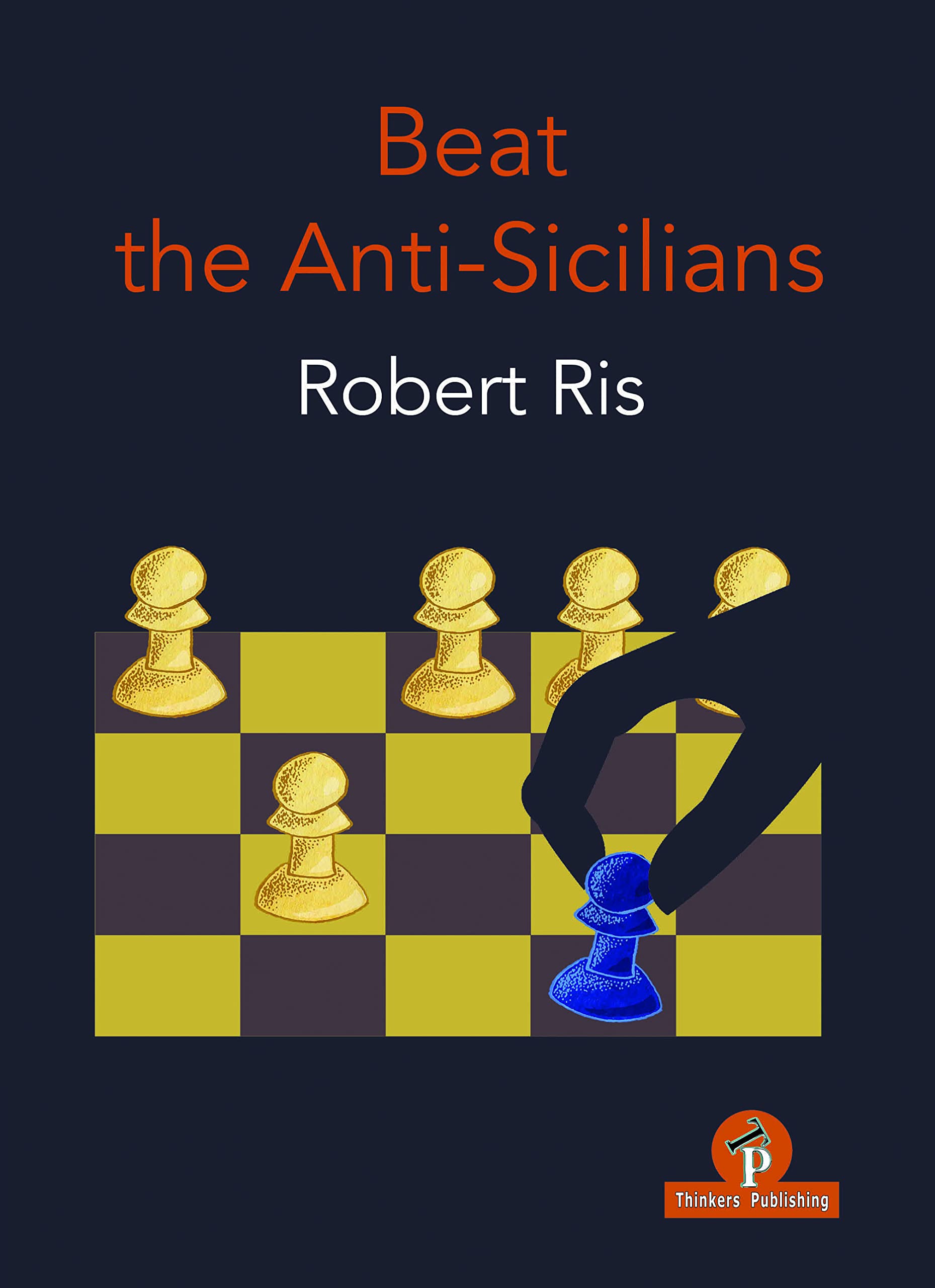

From the publisher:

“I have aimed to find a good balance of verbal explanations without ignoring the hardcore variations you have to know. In case you find some of the analyses a bit too long, don’t be discouraged! They have been included mainly to illustrate the thematic ideas and show in which direction the game develops once the theoretical paths have been left. That’s why I have actually decided to cover 37 games in their entirety, rather than cutting off my analysis with an evaluation. I believe that model games help you to better understand an opening, but certainly also the ensuing middle- and endgames.”

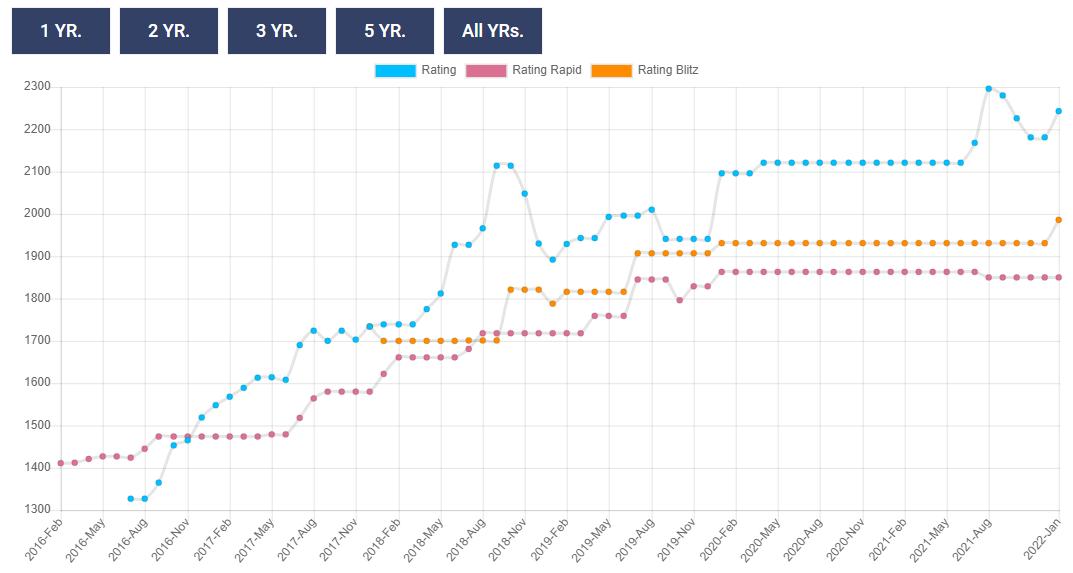

“Robert Ris (1988) is an International Master from Amsterdam. He has represented The Netherlands in various international youth events, but lately his playing activities are limited to league games.

Nowadays he is a full-time chess professional, focusing on teaching in primary schools, coaching talented youngsters and giving online lessons to students all around the world. He has recorded several well received DVDs for ChessBase.

Since 2015 he has been the organizer of the Dutch Rapid Championships. This is his fourth book for Thinkers Publishing, his first two on general chess improvement ‘Crucial Chess Skills for the Club Player‘, being widely appraised by the press and his audience.”

End of blurb.

In July 2021 we reviewed The Modern Sveshnikov by the same author and publisher. Robert sees his new book as a companion volume to the Sveshnikov volume. Indeed these two volumes taken together form a Black repertoire against 1.e4 using the Sicilian Sveshnikov.

This of course raised an issue with the book’s title. When we first received this book we were puzzled that only 2…Nc6 was considered (and why not 2…e6, 2…d6 etc.) which would be odd for a book suggesting it was for the second player dealing with the non-open Sicilian lines. The Preface clarified our confusion.

As with every recent Thinkers Publishing publication high quality paper is used and the printing is clear. With this title we return to the matt paper of previous titles. (You might have noticed from previous reviews that we encourage the use of the more satisfying glossy paper!)

Each diagram is clear and the instructional text is typeset in two column format, which, we find, enables the reader to maintain their place easily. Figurine algebraic notation is used throughout and the diagrams are placed adjacent to the relevant text. The diagram captions have returned.

There is no full Index or Index of Variations (standard practise for Thinker’s Publishing) but, despite that, content navigation is relatively straightforward as the Table of Contents is clear enough. However, we welcome an Index of Games.

Here are the main Parts:

- Rossolimo Variation

- Alapin Variation

- Anti-Sveshnikov Systems

- Odds and Ends

and here is an excerpt in pdf format.

A small plea to the publishers: Please consider adding an Index of Variations! We say this because of highly detailed level of analysis.

So, the first thing to bear in mind is that Black wishes to play the Sveshnikov Variation and therefore will play 2..Nc6 if possible. Chapter 1 therefore starts with:

- 4.Bxc6

- 4.0-0 Bg7 5.Re1

- 4.0-0 Bg7 5.-

- 4.c3

We note an error in the above entry in the Table of Contents which has 4…g6 instead of 4…Bg7 and the publishers acknowledge this error. 4.0-0 is the most popular alternative and then the capture and 4.c3 trails in third place.

The treatment of the material (for all Parts and Chapters) is by way of 36 (the Preface states 37) complete model games analysed in depth until around move 20 – 25 at which point the remainder of the moves are given without comment. This pattern is repeated throughout and is a successful one.

It might have been entertaining to pitch these chapters against the recent Rossolimo work by Ravi Haria but you will have to buy both books to amuse yourself in this way!

(from the aforementioned title:

Section 5 covers 3…g6 which is arguably the critical continuation. The author offers two different systems against this line: either capturing on c6 immediately or playing 4.0-0 and 5.c3.

so clearly both authors agree and identify 3…g6 4.bxc6 and 4.0-0 as the lines for student study.

Having examined the Rossolimo, which occupies the bulk of the content, we move onto the perhaps less critical but popular Alapin variation in Part II which, following,

is subdivided into three chapters viz:

- 4.Nf3 Nc6 5.d4

- 4.Nf3 Nc6 5.Bc4

- Other Systems

The “Other Systems” include a) d4 cxd4 5.Qxd4 and 5.Bc4 plus

b) 4.g3

Curiously the third most popular fourth move of 4.Bc4 (a favourite of Mamedyarov) is not given independent treatment but this omission is probably not too troublesome.

Part III, Anti-Sveshnikov Systems consists of four chapters:

- Various Anti-Sveshnikov

- Grand Prix Attack

- 2.Nc3 Nc6 and 3. Bb5

- Closed Sicilian

with Chapter 8, Various Anti-Sveshnikov breaking down into:

- a) 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d3

- b) 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Nc3

- c) 2.Nc3 Nc6 3.Nge2

of which a), The King’s Indian Attack is more likely to be seen at club level.

Again, an interesting exercise would be to take some of content of this book and put it up against the suggestions of Gawain Jones in his Coffeehouse Repertoire 1.e4 Volume 1. An exercise for the student! We’ve always imagined a tournament based on books ‘playing’ each other could have some academic merit.

Finally, we find ourselves in Part IV, Odds and Ends which covers exotic 2nd move (after 1.e4 c5) alternatives for White namely:

- 2.g3

- 2.b3

- 2.b4

- 2.a3

- 2.Be2

with a model game each. One could be picky and ask about 2.Ne2, 2.d3 but these are fairly transpositional.

However, for a repertoire book arguably there is at least one glaring omission and that is 2.d4, The Morra Gambit. We looked in the Alapin section for potential transpositions but without luck.

This book is a welcome addition to the author’s companion volume and provides a fine repertoire based around the Sveshnikov. As a bonus players of the Accelerated Dragon and Kalashnikov variants will also find material of benefit. More than that players of any flavour of Sicilian will find useful material in Part IV.

Enjoy!

John Upham, Cove, Hampshire, 26th January, 2022

Book Details :

- Hardcover : 248 pages

- Publisher: Thinkers Publishing; 1st edition (11 Jan. 2022)

- Language:English

- ISBN-10:9464201363

- ISBN-13:978-9464201369

- Product Dimensions: 17.15 x 2 x 23.5 cm

Official web site of Thinkers Publishing