Let me take you back 125 years, to the great London International Chess Tournament of 1899.

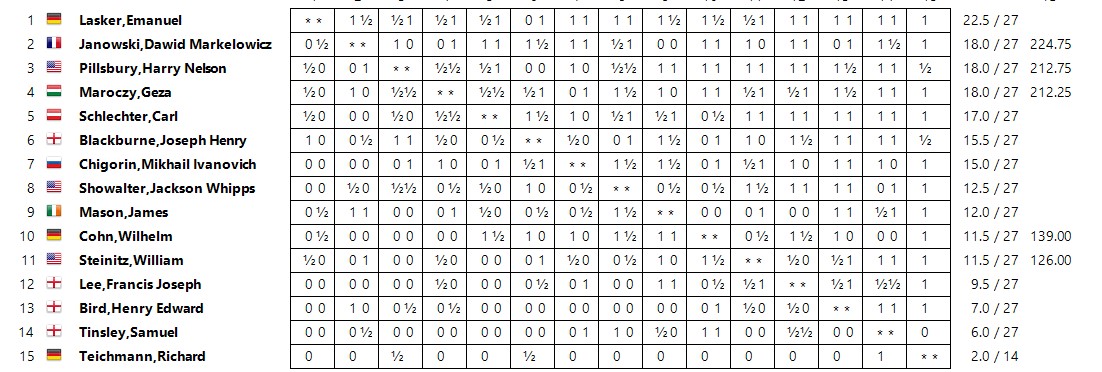

Most of the world’s strongest players were there: the first two World Champions, Steinitz and Lasker, Pillsbury and Chigorin, Maroczy and Schlechter, Janowski and Blackburne.

Here’s the cross-table.

There was also a second section, won by Marshall, ahead of the likes of Marco and Mieses, along with some local amateurs.

Two brilliancy prizes were awarded: to Lasker for his win against Steinitz and to Blackburne for his win against Lasker.

Here they are: click on any move for a pop-up window.

If you’re running such a prestigious event you’ll want some shiny new chess sets. The chipped and stained old pieces at the back of your equipment cupboard won’t do for the likes of Lasker and Steinitz.

But have you ever wondered what happens to those shiny new sets once they’ve been put away and the players have gone home?

It appears that, at some point after the end of the tournament, some sort of competition was held. I have no idea what the nature of the competition was, and how many sets were on offer. What I do know (or believe) is that one of the sets was won by a certain William Grasty.

William came from a working class family: his birth was registered in the first quarter of 1878 in Lambeth. His father, a stoker in a factory, died in 1884, and, by the 1891 census, young William was living with his aunt in Southwark. I don’t at the moment know whether he acquired this board immediately after the 1899 tournament, but by 1901 he was moving up in the world, living in lodgings in Wood Green and working as a commercial clerk.

He married Arabella Edith Attwood in 1904, but, tragically, their first child, William Arthur, born in 1909, died before reaching his first birthday. By now the family had settled in Lewisham, and the 1911 census found him still working as a commercial clerk. Later that year, another son, named Leonard Francis, was born. Soon afterwards the family moved to Islington, where a daughter, Muriel Florence, was born in 1913.

By 1921 the family had left London, moving to Southsea, where William was working for Weingarten Bros Ltd, Corset Manufacturers as an accountant. As well as William, Arabella and their children, the household included two boarders: the sisters(?) Dorothy and Elizabeth Kilby, both schoolteachers. At the time, Portsmouth was known as the corset capital of the world (who knew?) and they’re still made there now. Many of my relations were employed manufacturing corsets in Market Harborough, but that’s a story for another time.

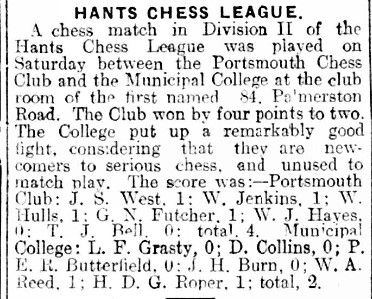

There’s no evidence that William ever played competitive chess, but his son certainly did. I guess they played at home using the board from the 1899 tournament, trying to emulate the play of Lasker and his colleagues. Between 1928 and 1931, Leonard was a student at Portsmouth Municipal College, playing on top board for their chess team. They started off with friendly matches against Portsmouth Chess Club before graduating to the second division of the local league.

In 1931 Leonard graduated with a BA General Degree with Honours and a First-Class Distinction in Maths awarded by London University and took a job as a Customs and Excise Officer. Like so many others before and since, on finishing his studies he stopped playing competitive chess.

We next meet him in Manchester in 1937, where he married a local girl, May Taylor Shaw, the daughter of a sheet metal worker.

By the time of the 1939 Register, Leonard and May, along, perhaps, with their chess set, had moved back south, now living in Stanmore, North London. They were blessed with three children, Barbara (1937), Robert (Bob) (1939) and Victor (Vic) (1943).

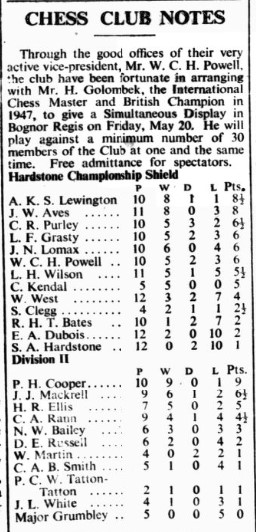

At some point the family moved down to Bognor Regis, on the West Sussex coast, not all that far from Portsmouth. It was there, in 1948, that Leonard returned to competitive chess, joining the local club. As it happens, the Bognor Regis Observer up as far as 1959 is available online. During this period they ran a regular column featuring local chess news, contributed by the pseudonymous King’s Pawn and The Rook, so we have a lot of information about his chess career over the next decade or so.

You’ll see that he soon established himself as one of their stronger players, although it must be said that Bognor were no match for the likes of Brighton and Hastings. What they did have, though, was some very effective and ambitious administrators. You might notice, for example, the name of Joseph Norman Lomax, who would do much to put his home town on the chess map.

Here they are, in 1949, inviting a very distinguished guest to give a simultaneous display.

In fact Harry Golombek took on 33 (or 34, depending on your choice of newspaper) opponents, losing two games and drawing six, including his game against Grasty. He stayed on overnight, the following day playing another simul against five teams of consultants, drawing two and losing one, against Grasty and his veteran partner Stephen Arthur Hardstone (1873-1952), a retired civil service engineer.

Golombek would give a number of simultaneous displays at Bognor over the next few years. Here’s a photo of one of them.

The games we have for Leonard Grasty in this period, sadly, don’t show him in a very good light. If he’d captured the bishop on move 13 in this game he’d have been fine rather than having to resign two moves later.

And here, in an equal position, he found one of the worst moves on the board, allowing a mate in one.

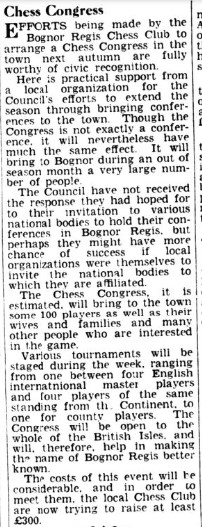

In 1952, the local organisers had a big idea.

In fact the first congress would be held the following year, run by Joseph Norman Lomax (later, after his second marriage he’d style himself Norman Fishlock-Lomax), continuing very successfully until 1969.

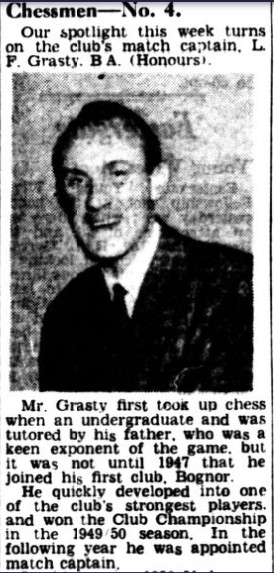

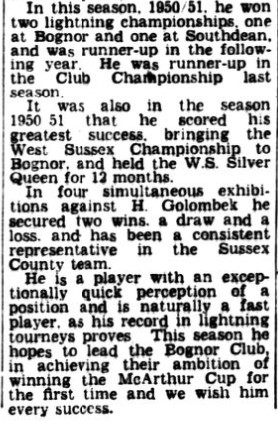

Later that year, Leonard Francis Grasty was the subject of a profile in the local paper.

Was his speed of play responsible for the careless mistakes he seems to have made? Perhaps someone should have advised him to slow down.

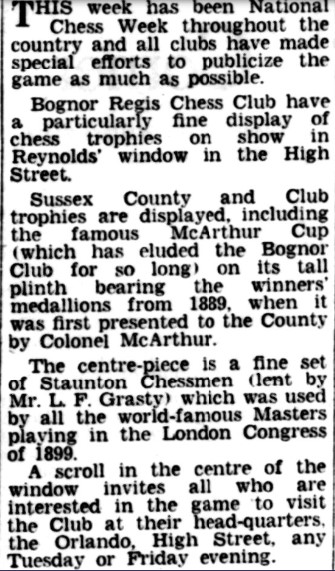

In 1954 Bognor Regis Chess Club put on a display of chess trophies in a local shop window for National Chess Week.

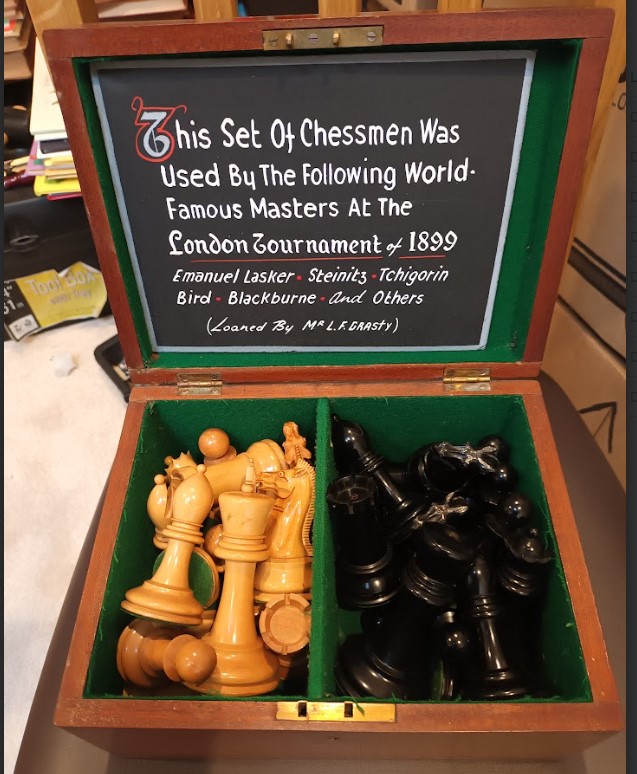

There you have it. Leonard had inherited the chess set which his father had won perhaps more than half a century earlier.

Here it is.

It didn’t help him in this game against one of Brighton’s young stars, where he had to resign after only nine moves, having fallen for a rather well known opening trap. The earliest example in MegaBase dates from 1908, but the variation itself dates back to Blackburne – Paulsen (Vienna 1882), where Black won after 8… Ng4.

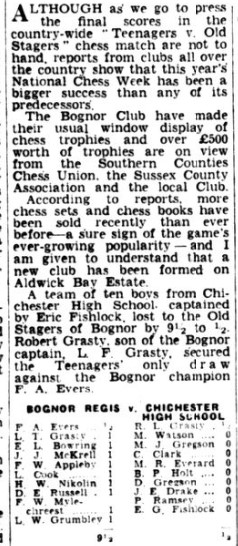

The following year’s National Chess Week also featured the display of chess trophies, along with a Teenagers v Old Stagers match in which Leonard and his older son Robert were on opposite sides.

A few months later, Bob took part in the Southern Counties Junior Championship, held as part of the 3rd Bognor Regis Congress, scoring 3/7. The other competitors included Michael Lipton, who would later achieve fame as a problemist. He returned the following year, when he managed half a point more, which was half a point less than the score achieved by Stewart Reuben.

Leonard continued his chess activity in Bognor throughout the 1950s.

Here’s a photograph from a club prizegiving from 1958, where Leonard shared the club championship with local journalist Alan Lawrence Ayriss (1934-2006), who, as it happens, has a very distant family connection with me (the 2nd cousin 2x removed of the husband of my 3rd cousin 2x removed). He’s holding a Bell book: The Art of Checkmate (Renaud & Kahn), which was published in that edition in 1955. The book is still within the family: an inscription inside reads “BOGNOR REGIS CHESS CLUB Presented to L.F. Grasty RUNNER UP LIGHTNING TOURNAMENT 1958. We can also see copies of Edward Lasker’s Chess for Fun and Chess for Blood in a 1952 edition and Reinfeld’s Improving Your Chess (1954).

This, captioned 1958, shows Bob seated second left, perhaps from the same event as the previous photo.

By December 1959 Leonard had been joined by his younger son, Victor, who was up for selection for a match against Worthing. But, at that point, the online run of the Bognor Regis Observer comes to an end, so I have, at the moment, little information about what happened next.

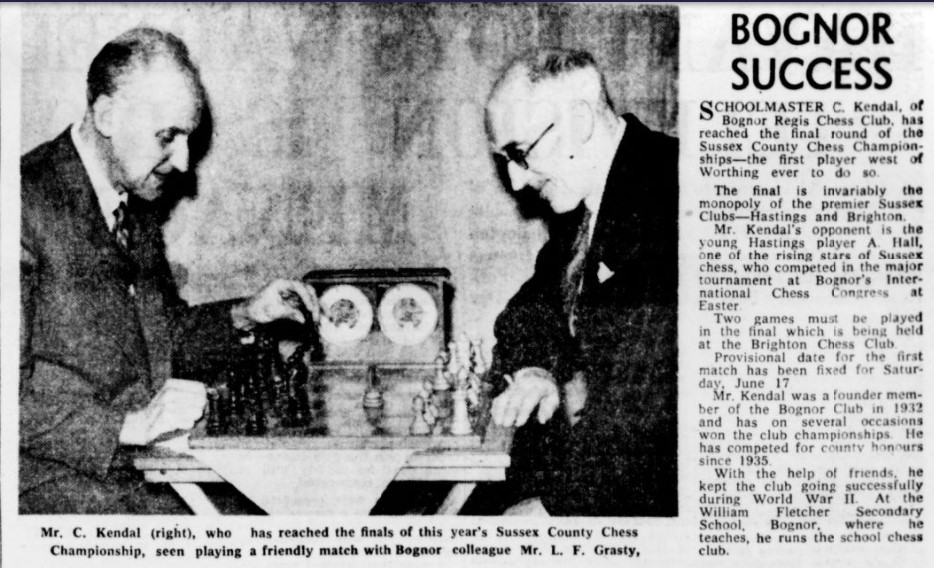

We do have a photograph from 1961 where he’s playing a friendly game against William Clifford Kendal (1902-1988).

In this game from 1966, he chose an unsuccessful plan in the early middle game, allowing his opponent to bring off a smart finish.

It’s unfortunate that the games of Leonard Grasty currently available have, so far, been rather unimpressive losses with the black pieces. Perhaps he played much better with white.

We do have a draw, from what must have been towards the end of his chess career, against a very strong opponent in Geoffrey James (no relation, but he played for my club, Richmond, for a few years in the 1970s). He was perhaps a bit lucky, though, as Geoffrey uncharacteristically missed a few winning chances.

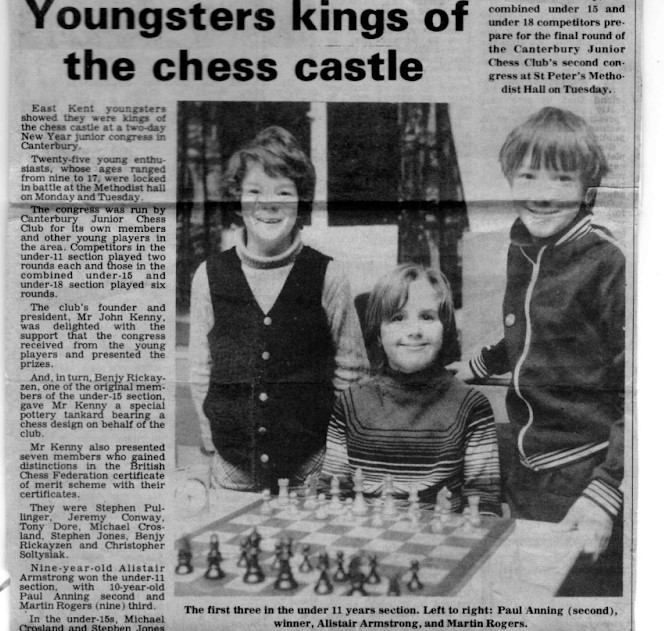

This was a family steeped in chess: they counted Harry Golombek as a family friend. Bob and Vic’s sister Barbara recalls (although the Guardian journalist doesn’t) once going on a date with Leonard Barden. Barbara later married a man named Michael Armstrong. Their son Alastair, born in 1967, continued the family chess playing tradition into a fourth generation.

Leonard must have been very proud of his grandson’s success. He died in 1981, when Alastair was still quite young, but he still has many very fond memories of his grandfather, who encouraged his early interest in chess.

It was only right, then, that it was Alastair who would eventually inherit his great grandfather’s London 1899 chess set.

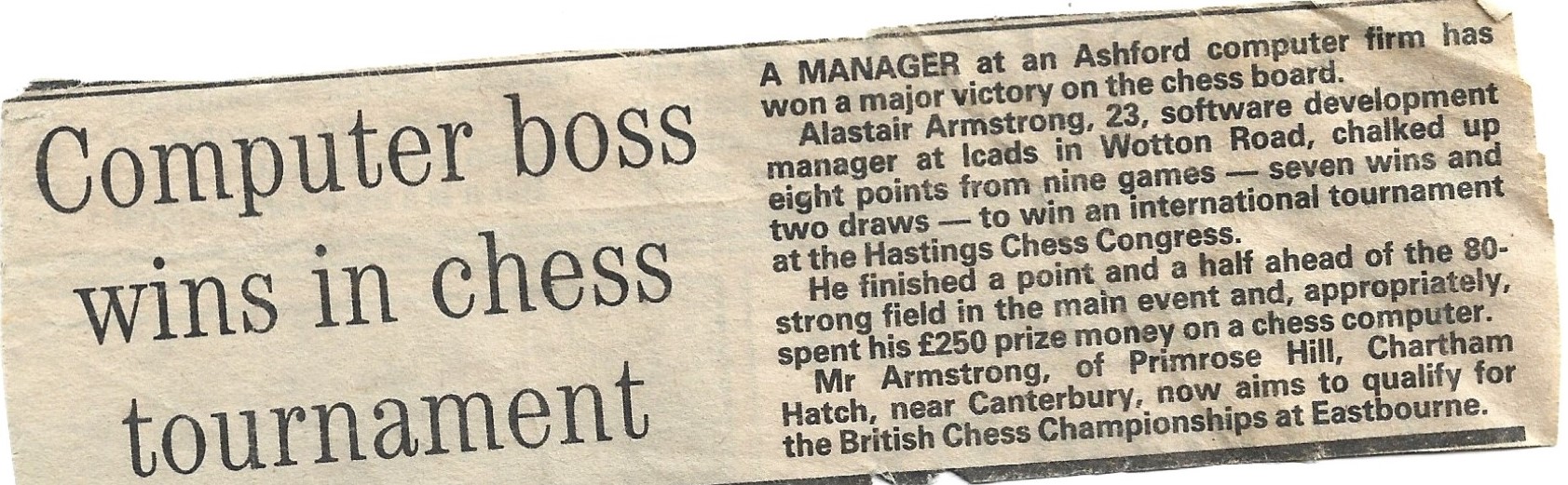

Here ‘s Alastair again, 13 years later, winning the Main A Section of the Hastings Congress (the Main A wasn’t the main event at the congress, but never mind).

Shortly afterwards, Alastair moved abroad, but, more than 30 years on, he’s now returned to England, deciding to take up chess again, and by chance living just round the corner from the Chess Palace.

He still has the 1899 chess set and board, and provided the photographs above. His son, though, shows little interest in the game.

So there you have it: the story of a chess set and board first played on, perhaps, by Emanuel Lasker, spanning four generations of the same family and 125 years.

Join me again soon when we’ll return to London in 1899.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

ChessBase/Stockfish 16 for game analysis

Alastair Armstrong and the Grasty family, for the story and photographs

Brian Denman for providing some of Leonard Grasty’s games

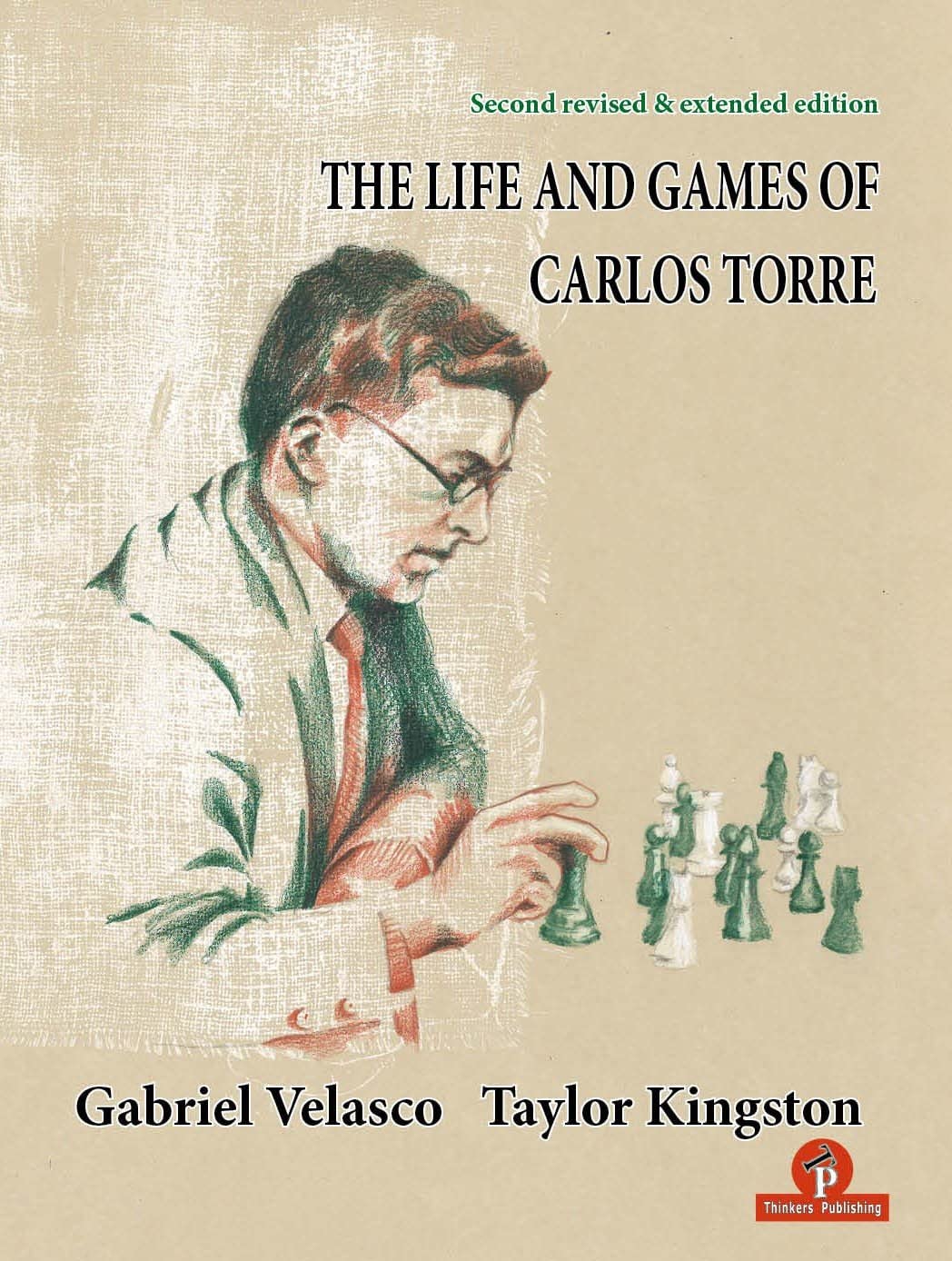

This is the starter book (0-500 range) explaining what a game of chess is really about. If you just want to learn the basics, this is for you.

This is the starter book (0-500 range) explaining what a game of chess is really about. If you just want to learn the basics, this is for you.