From the back cover:

“The astounding success of How To Study Chess on Your Own made clear that there are thousands of chess players who want to improve their game – and do (part of) their training on their own. The bestselling book by GM Kuljasevic offered a structured approach and provided the training plans. Kuljasevic now presents a Workbook with the accompanying exercises and training tools a chess student can use to immediately start his training.

Kuljasevic wanted his exercises to mimic the decision-making process of a real game. His focus is on training methods that encourage analytical thinking. Most workbooks offer puzzles and puzzles only. But with this book, you will be challenged by tasks like:

- Solve positional play exercises

- Find the best move and find the mini-plan

- Play out a typical middlegame structure against a friend or an engine

- Simulation – study and replay a strategic model game

- Analyze – try to understand a given middlegame position

The Workbook is designed for self-study, but is also useful for chess coaches and teachers and can be applied in one-on-one lessons, as well as in study groups in chess clubs, schools or online classes. This first volume is optimized for chess players with an Elo rating between 1800 and 2100 but is very accessible and useful for any ambitious chess player.”

About the Author:

“Davorin Kuljasevic is an International Grandmaster born in Croatia. He graduated from Texas Tech University and is an experienced coach. His bestselling books Beyond Material: Ignore the Face Value of Your Pieces and How To Study Chess on Your Own were both finalists for the Boleslavsky-Averbakh Award, the best book prize of FIDE, the International Chess Federation.”

Before we continue you might like to inspect this preview from the publisher’s website (product page here), which will give you an idea of the layout and show you some of the exercises. If you prefer, you can see sample pages from the Kindle edition here.

A quick word first. I have a large backlog of books to review and little time in which to review them, so, in an attempt to catch up, I will be writing much shorter critiques on the titles in my in-tray than I have done in the past.

I reviewed the author’s previous volume with some enthusiasm here, so was eager to see this workbook, especially given that, in terms of rating, but not interest in improving my game, I’m within the book’s target range.

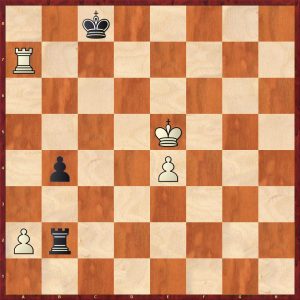

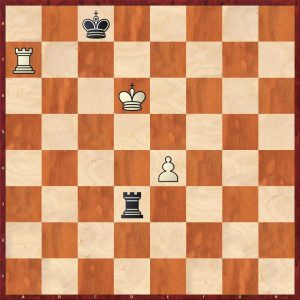

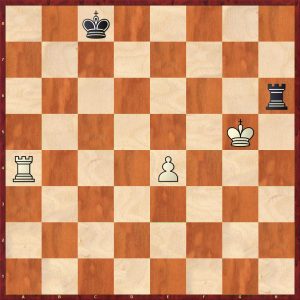

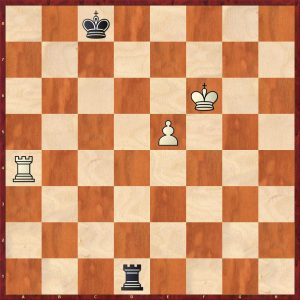

The main body of the book comprises fifteen sets of eight puzzles. We start with five sets on tactics, gradually increasing in difficulty, each set including six ‘find the hidden tactic’ exercises, followed by two ‘tactical analysis’ exercises.

This seems excellent to me. My impression has always been that, at my level, games are much more often decided by spotting or missing exactly this sort of tactical point than by brilliant combinations and sacrifices. The Hidden Tactic exercises present a position and a three-move sequence, in which you have to find the tactical opportunity that was sometimes missed over the board. The analysis questions invite you to analyse several different lines and decide which is best.

Then we have five sets on Middlegame Training. Here we have six positions where you have to find the correct mini-plan, followed by two simulation exercises where you play through part of a game and are awarded points, in the style of Daniel King’s How Good is Your Chess feature in CHESS, for finding good moves.

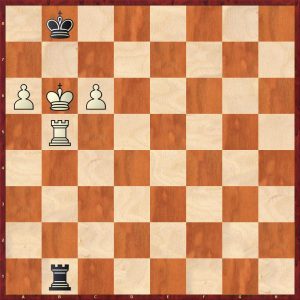

Finally, there are five sets on Endgame Training to test you on this most important phase of the game. Here, each set gives you four endgame analysis questions where you have to analyse several lines. Then you have two endgame simulation exercises, followed by two positions for you to play out against a training partner, coach or engine. I’m very much in favour of this and believe that playing out endgame positions should be an important part of every player’s training.

In my day, 50-60 years ago, reading books was, for most of us, just about the only option for chess improvement. Now, of course, there are many more options. As was clear from his previous book, Kuljasevic has put a lot of thought into the most efficient training methods, and into what works best within the framework of a book, and has done an excellent job in selecting material appropriate for his target market.

If you think this book might appeal to you, again I’d refer you to the previews linked to above.

As is usual from this publisher, production values are high. The layout could have been more generous and easier to follow, but this would have necessitated more pages and cost you more money.

If you’re rated between 1800 and 2100, ambitious to improve your rating, are prepared to take time out for serious study and enjoy reading books, I can strongly recommend adding this to your library. Further volumes for lower and higher rated players are promised: I look forward to reading these in due course.

Richard James, Twickenham 26th July 2024

Book Details:

- Softcover: 224 pages

- Publisher: New in Chess; Workbook edition (31 Jan. 2023)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:949325755X

- ISBN-13:978-9493257559

- Product Dimensions: 17.15 x 1.5 x 23.01 cm

Official web site of New in Chess.