Jack Redon was one of the elder statesmen at Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club for the first 20 years or so of my membership. On completing my studies in 1972 I joined the committee and got to know him well.

Jack was a pretty strong player who was known for his artistic interests. He was a commercial artist by profession, designing things like LP sleeves, but had a particular interest in amateur dramatics and seemed to be involved with every artistic society in the area.

He seemed to live a life of some affluence, sharing a large Victorian house near Richmond Bridge with his wife and sister. Richmond Junior Chess Club would later spend many years in another large house on the same estate, which had been converted into a community centre.

(I also visited the house regularly years later, to teach a chess pupil whose name, coincidentally, was also Jack.)

If you have an interest in 19th century domestic architecture it’s well worth a stroll round these roads. You can also read more about the Twickenham Park estate here and here.

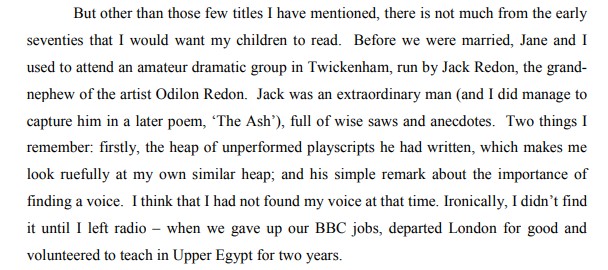

The distinguished poet John Greening also knew Jack very well at about this time, describing him well in a memoir.

He was indeed an extraordinary man, full of wise saws and anecdotes. He did tend to repeat them time and time again at every committee meeting, but, given his age and seniority within the club, we forgave him his eccentricities. He generously made his residence available for these meetings in the mid 1970s, and, when one of our younger members suggested we might meet in a pub instead, he didn’t take kindly to the idea.

While John Greening recalls the unperformed playscripts, I recall the skirting boards being lined with paintings, which, like his plays, were created for his own pleasure rather than for profit. My recollection is that they may well have been in the style of Odilon Redon: and he also told us that he was Odilon’s great nephew. But was it true?

Almost certainly not. Odilon (Wiki) came from a wealthy slave-trading family and, although born in Bordeaux, was conceived in New Orleans, like Paul Morphy the son of a Creole mother. Jack’s family background was very different. It has little to do with chess, so if you want to see some moves you’ll have to jump ahead, but if you’re interested in social history you’ll want to read on. Or even Redon!

Redon is a rather unusual French surname specifically associated with the South West of the country. But let me take you back more than 300 years, to 1722. We have a record of a clandestine marriage for one Peter Redon, a weaver living in Stepney. If you see a weaver with a French surname in that part of London at that time you’ll probably assume that he was a Huguenot. Maybe, but Jack’s ancestors later embraced the Jewish religion, calling their children Elias, Abraham and Reuben, Leah, Esther, Rachel and Rebecca.

By 1798 the Redons had crossed the river to Southwark, where Elias (a labourer) and his wife Rachel were accused of running a brothel. In 1839 Abraham Redon, perhaps a son of Elias and Rachel, was on the other side of the law, a victim of a crime. He was working as a toll collector at the Cambridge Heath tollgate in Hackney and, while he was sleeping, two of his assistants, Henry Walker and John Hollingshead, stole his takings. Both were found guilty at the Old Bailey and sent to prison.

In the 1841 census we have John and Leah Redon, along with their children Alfred (20) and Esther (15), living in Woolwich, with John working as a toll collector. Alfred’s occupation is not legible, but certainly not ‘toll collector’. Woolwich is not all that near Hackney. Alfred was actually Abraham Alfred, so was John actually Abraham John, or were Abraham and John brothers sharing an occupation?

Esther, who had an illegitimate daughter, spent much of her later years in and out of the workhouse, their records describing her as a Jewess. Abraham Alfred, showing the first sign of artistic talent in the family, worked as a painter and signwriter. He married Rose Sawyer in about 1854 (or perhaps he didn’t: I haven’t been able to find a marriage record), but, tragically, none of their first six children lived to see their seventh birthday. Their two youngest sons did survive, though: John Edward, born in 1867 (baptised in the Church of England) and Reuben Alfred, born in 1869. Rose died in 1887, and by the time of the 1891 census Abraham Alfred, unable to look after himself in old age, was in the workhouse, where he died the following year.

So far, the Redon family history is one of poverty and tragedy, very different from the affluent environment in which their namesake Odilon grew up. But Jack gave the impression of being fairly affluent himself. What happened to change the family’s fortunes?

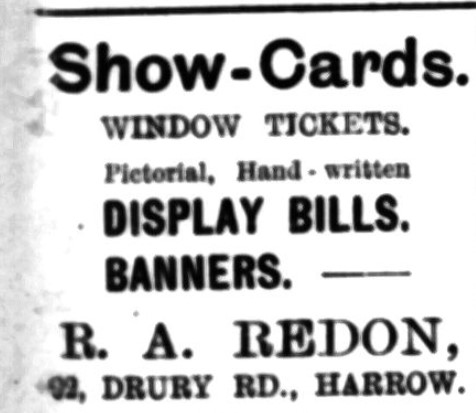

Reuben Edward Redon, continuing the family’s artistic tradition, making a living first as a glass embosser (in 1901 he was living in the road running alongside my old school, Latymer Upper), and later as a designer of showcards, running a business in Harrow for several years.

He was married, but had no children, and died, by that time living near his brother in Peckham, in 1927.

We need to follow John Edward Redon and see what happened in his life. In 1871 he was in Manor Place, Walworth (just south of Elephant and Castle) with his parents, brother and aunt. In 1881 the family were still at the same address: John had left school and was working as an office boy. In 1891, his mother having died and his father in the workhouse, the two brothers were living in a boarding house near the Old Kent Road, the cheapest place on the Monopoly board. John was now, following in his father’s footsteps, working as a signwriter.

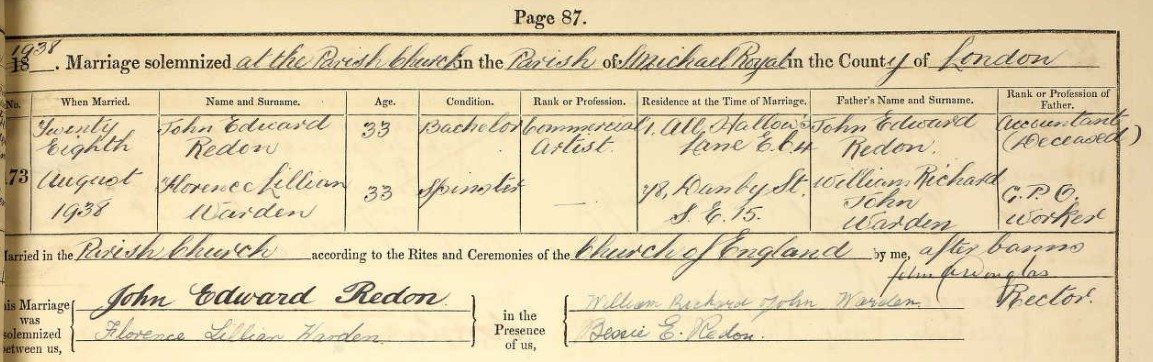

By the 1901 census John was working as a clerk for London County Council, and boarding just south of Waterloo Station, right by Westminster Bridge. Also there was a dressmaker named Bessie Emma Varney, and, in October that year they married. Bessie’s family seems to have been London working class, and, her mother having died when she was only 5 years old, she and her younger sister were brought up by relatives. John and Bessie had three children, René Bessie (1902), John Edward, named after his father, who would always be known as Jack (1905) and Reuben Ernest (1908-1912).

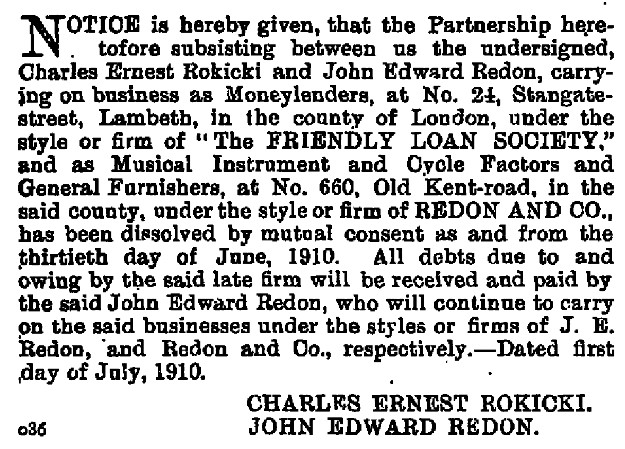

At some point, I’d guess from circumstantial evidence, round about 1903, John left his job with the council and formed a partnership with Danzig born Charles Ernest Rokicki. They started two companies, a moneylending business based at John’s home address in Lambeth, and a shop in the Old Kent Road.

In 1907, John, like his grandfather before him, fell victim to a robbery when a habitual criminal named Reuben Vaughan (there are a lot of Reubens in this story) paid for a gramophone and 46 records using a forged cheque, receiving a sentence of six years penal servitude.

Their partnership was dissolved in 1910, with John apparently buying his partner out.

The family business of Musical Instrument and Cycle Factors and General Furnishers must have been successful. In 1911 they were living above their Old Kent Road shop. John, perhaps no longer involved in the moneylending business, was described as a Dealer in Musical Instruments (Gramophones), while Bessie was assisting in the business. They were able to afford to employ a Domestic Servant (Mother’s Help) to give Bessie a hand in looking after the children. Young Reuben, sadly, would die the following year.

Within the space of two decades the family had gone from workhouse poverty to employing a servant. At some point between 1911 and 1921 they moved their shop to 185 Queen’s Road, Peckham.

During the First World War John was called upon to serve his country as a clerk in the Admiralty: he was still there in 1921. Bessie, who seems to have been a remarkably strong and ambitious woman, was running the business on her own, describing herself in the 1921 census as a Music Seller. René had no occupation recorded, although I’d guess she was helping out in the shop, while 16-year-old Jack was a part-time art student.

As well as studying art, Jack was becoming interested in the Art of Chess, joining Battersea Chess Club.

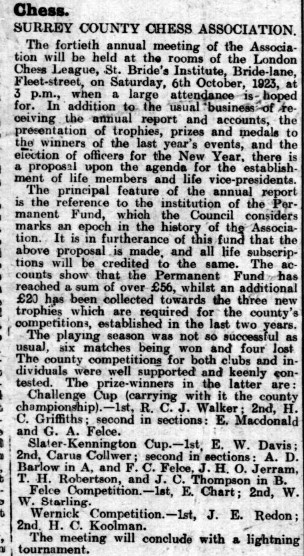

Here he is, in 1923, becoming the second ever winner of the Wernick Cup, which is still, more than a century on, the fourth division of the Surrey individual championship. In 1962 the name of another promising young player, RD Keene would be engraved on the trophy. It’s easy to forget that, in these days of preteen grandmasters, a century ago it was relatively unusual for teenagers to take part in competitive chess against adults.

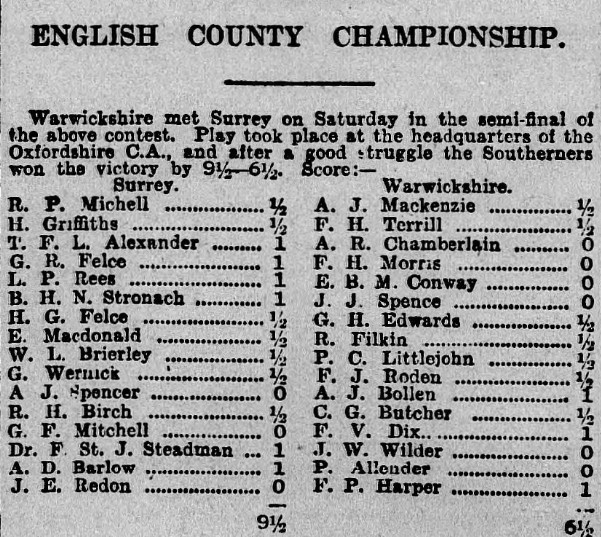

His would be a solid rather than a meteoric chess career, though, developing into a strong club player who, by 1926, was good enough to be selected for an important county match.

He lost his game, but Surrey’s greater strength on the higher boards saw them through. Crossword addicts will notice an anagram on the other side.

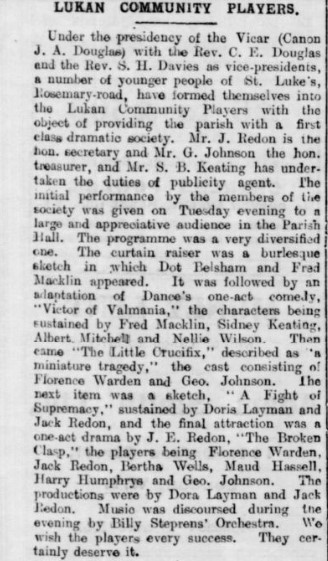

While he continued playing chess, Jack soon took up a new interest, in amateur dramatics, setting up a group in his local church. (By now the family were very much Church of England.)

You’ll note the name Florence Warden, also known, from what I recall, as Flossie, who was living with her grandmother and step grandfather, having lost her mother in childbirth when she was only one year old.

John died in early 1931, and it’s quite possible that Jack now had to take a greater role in running the family business. He still had time to play chess, though, and by 1935 had reached top board for Battersea.

He had also reached the top section of the county championship, but in this game from 1937 he was out of his depth against a strong opponent. (For this and all games in this article, click on any move for a pop-up window.)

In this county match game from the same period against an electrician from Brighton, he played an opening gambit and probably didn’t have enough for the pawn, but when he threatened a queen sacrifice his opponent carelessly overlooked it.

and probably didn’t have enough for the pawn, but when he threatened a queen sacrifice his opponent carelessly overlooked it.

The amateur dramatics must have been going well too, as in 1938 he married his fellow thespian Florence Warden.

You’ll immediately note Jack’s artistic signature, appropriately for a member of a family involved in signwriting. There are two other things to note as well. The marriage took place not locally but in the City of London, at St Michael Paternoster Royal, a church associated with Dick Whittington, which had been rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren after the Great Fire. He gave an address nearby, which, I suspect, was a dummy address enabling him to marry there. You’ll also see that his late father’s occupation was given as Accountant, which doesn’t tie in with other records. Perhaps he did the accounts for the family shop, or maybe it was a euphemism for Moneylender.

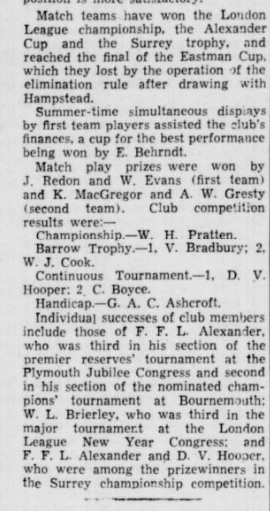

His marriage certainly didn’t stop his chess career: at this point he was very active in both club and county chess, winning a prize for one of the best performances in the Battersea first team. If you look at some of the other names here you’ll observe that it was a very strong club at the time.

Although marriage didn’t stop Jack playing chess, the war did. Just three days before this report appeared, and with war just having broken out, a national registration of the civilian population was taken.

Bessie, now in her late 60s, was still running her shop in Peckham, selling gramophone records, musical instruments and cycles. Jack and Florence were living there as well, as was Florence’s elderly grandmother Matilda, an old age pensioner. Florence had a temporary job operating an Elliott-Fisher bookkeeping machine. Jack was described as a designer of sight tests on glass, etching and stencil cutting.

Most of London’s chess clubs, including Battersea, closed for the duration, so there was little opportunity now for Jack to play chess. Matilda died in 1942, and Bessie in 1943. I presume Jack and René would have inherited the business, selling it and moving, along with Florence, to their new home in Twickenham. They must have done pretty well for themselves: not only were they able to afford a large house in a desirable area, but it seems that they no longer needed to work for a living. Not quite Old Kent Road to Mayfair, but still pretty impressive.

Jack threw himself enthusiastically into his theatre and chess hobbies, which would dominate the rest of his life. In 1944 he was a member of the Twickenham Community Players, writing and producing plays for them, just as he had done back in Peckham. They even met for rehearsals at his house (was he the founder, I wonder), but sought larger premises at the new Georgian Club in Richmond.

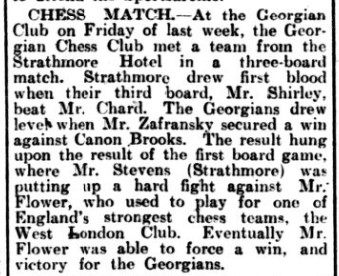

Jack joined Kingston and Thames Valley Chess Club, which, like Barnes Village, continued meeting during the war. He also rejoined Battersea, who resumed their activities in 1945, where he would win their club championship in 1960. There was now no active chess club in Richmond or Twickenham, though, and this was something he wanted to change. He started a chess section at the Georgian Club, which had modest beginnings.

Retired schoolmaster Phillip Flower, who lived round the corner from Jack, had been strong enough to play in the Major Open at the 1911 British Championships, as well as the First Class in 1921 and 1922, where his victims included future stars Fairhurst and Buerger. Jacob Zafransky ran (or at least he did in 1939) a radio and cycle shop again just round the corner from Jack: there might have been a work connection as his business was very similar to that of Jack’s family.

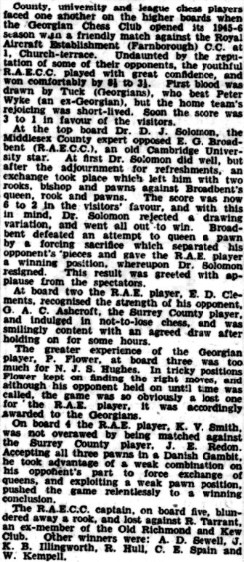

By the following year they were able to raise a dozen players for a match against an established club.

Jack had managed to recruit two very strong players for the top boards: eccentric philosopher, schoolteacher and much else Dr JD (John David) Solomon, and civil servant Geoffrey Ashcroft, who, although he lived in East Sheen, was a friend and colleague from Battersea Chess Club. It’s pleasing to see that Reginald Tarrant (and it was lovely to hear from his son-in-law recently) provided a link with the ‘Old Richmond and Kew Club’.

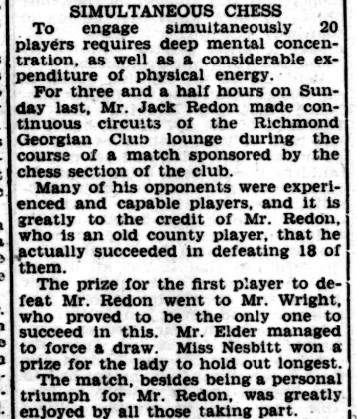

The following March, Jack gave a simultaneous display, which proved very successful.

The prizewinning Miss Nesbitt must have been Violet Ella Nesbitt Kemp, an architect’s daughter, who would, some three decades later, rejoin what was by that point Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club. Remarkably, being born in 1888 and dying in 1992, she lived to the age of 103 . I was led to believe she was an actress, but perhaps only on an amateur basis, which might have been where she met Jack.

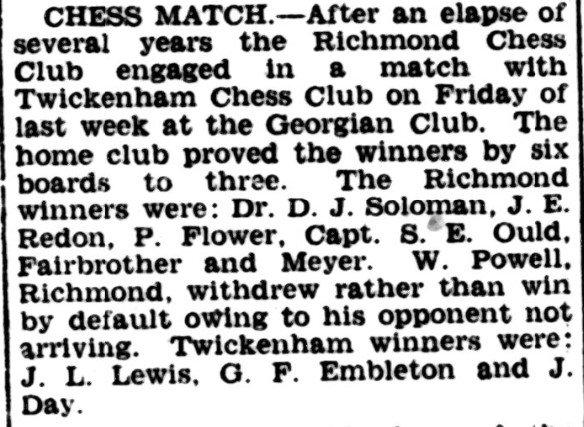

In 1947 a match was played against Twickenham Chess Club, which had recently reformed, the previous club of that name having folded some years previously. Richmond seem to have dropped ‘Georgian’ from their name, now established as Richmond Chess Club.

Captain Samuel Ould (a civil servant in 1939, although he always used his military rank from the First World War) provided another link with the previous Richmond and Kew Chess Club, while Ted Fairbrother would remain a member into the 1970s.

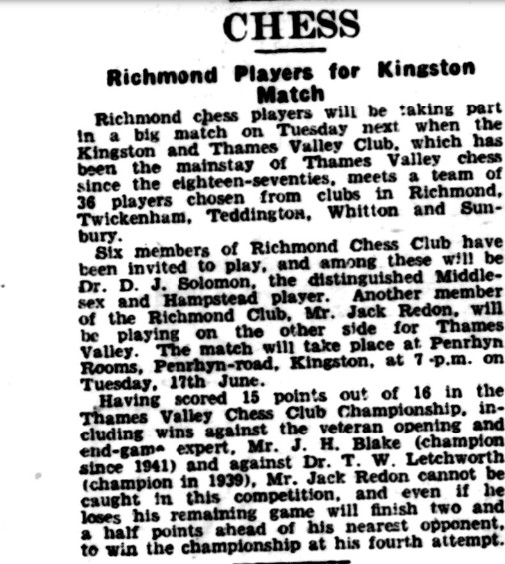

A few months later Kingston and Thames Valley Chess Club staged a megamatch against a combined Richmond and Twickenham team (just as they did again in 2022). The Teddington club would have been the NPL, the Sunbury club British Thermostat and the Whitton club perhaps Old Latymerians.

You’ll see that Jack, as their club champion, represented Kingston on this occasion. By beating Blake, who had, many decades earlier, beaten Rev John Owen, who had beaten Morphy, this gave him a Morphy Win number of 3.

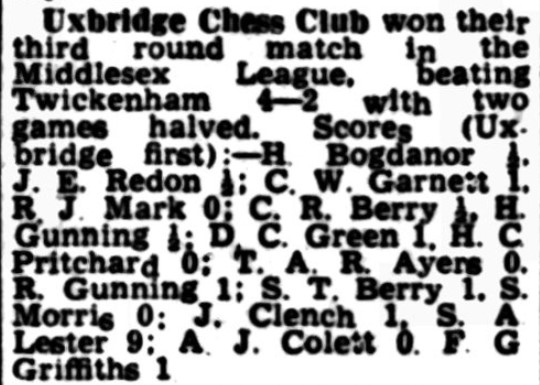

Being a member of three chess clubs wasn’t enough for Jack Redon. He also played for Twickenham in the London and Middlesex Leagues. (I haven’t found any online information about the founding of the post-war Twickenham Chess Club, but I suppose he might have been involved.)

Here he is, playing in a match against Uxbridge in 1950.

His opponent here, Harry Bogdanor, was a rather dodgy pharmacist (see discussion here) and the father of political scientist (and David Cameron’s tutor) Vernon Bogdanor. FG (Griff) Griffiths was still involved with Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club into the early 1970s. I also have an interest in SA Lester, who, I hope, was precision tool maker and amateur musician Sydney Arthur Lester. At any rate he was the only SA Lester I’ve been able to find in the Twickenham area at the time. Perhaps I’ll tell you more in a future article.

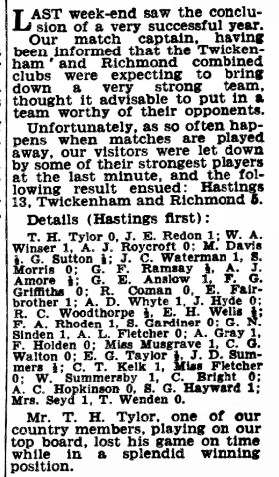

Richmond and Twickenham Chess Clubs were clearly working closely together, in 1952 sending a combined team down for a friendly match at Hastings. Jack scored a fortuitous win on top board against an English international.

You’ll notice endgame study expert John Roycroft on Board 2. I ‘m sure AL Fletcher was L Elliott Fletcher, author of Gambits Accepted, and Miss Fletcher his daughter Lesley, who would later marry Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club’s Robert Pinner. I lose to George Anslow in the corresponding fixture in 1974.

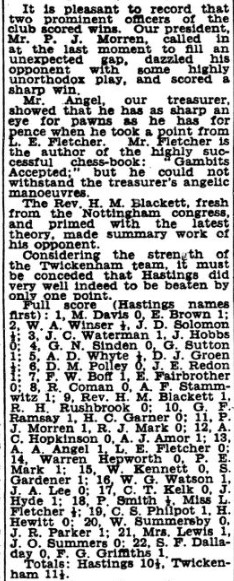

In 1954 the team visiting Hastings, although billed just as Twickenham, was quite a lot stronger, seeming to have recruited some players from other Middlesex clubs rather than Richmond for the match.

I don’t know much about Edgar Brown, whose club was sometimes billed as Wembley & Hampstead. He won the RAF Championship and 1944 and shared 1st place in the 1950-51 British Correspondence Championship. Another Twickenham player in this match was was chess administrator and bigamist Alan Stammwitz (see this thread).

Playing on second board in the 1956 Hastings v Twickenham match he defeated a highly respected opponent with an original sacrifice in the Max Lange Attack. Although it wasn’t quite sound, his opponent, a bank official who, like all the best chess players at the time, had retired to Hastings, was unable to cope, rapidly going down in flames.

Throughout this time, Jack remained very active in amateur dramatics. He never had the looks of a leading man, but excelled in comic and character roles. In 1946 his portrayal of Sir Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night was ‘handled with a delightful touch and never over-played’, while in 1949 he was ‘well cast as the cowardly Oswald’ in King Lear. I’m not sure whether that was a compliment or an insult.

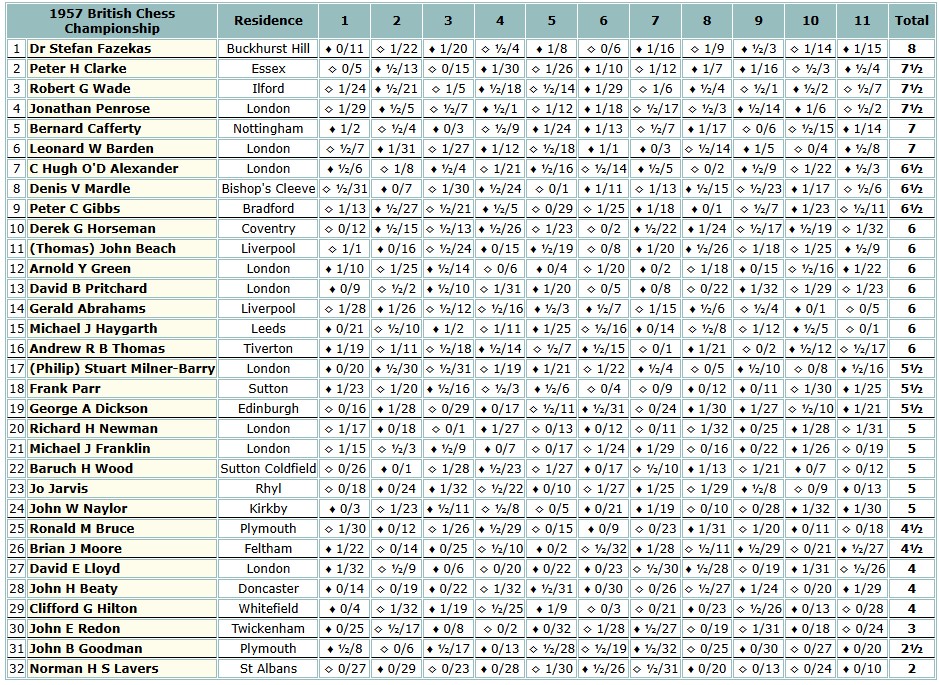

Although he was an enthusiastic participant in club and county chess, tournaments were, with one exception, not for him. In 1957 he successfully entered the qualifying tournament for the British Championship, held that year in Plymouth.

In 1956 he’d appeared in the BCF Grading List at 5a, about 2050 Elo, and remained round about that level for several years – a pretty strong amateur who could – and did – hold down a high board in club matches and a low board in county matches.

Here, he found the going tough, finishing on just 3 points out of 11.

He was well beaten in this game, where his opponent exploited his space advantage with a central breakthrough.

He demonstrated his tactical skills in this game, winning with a powerful kingside attack.

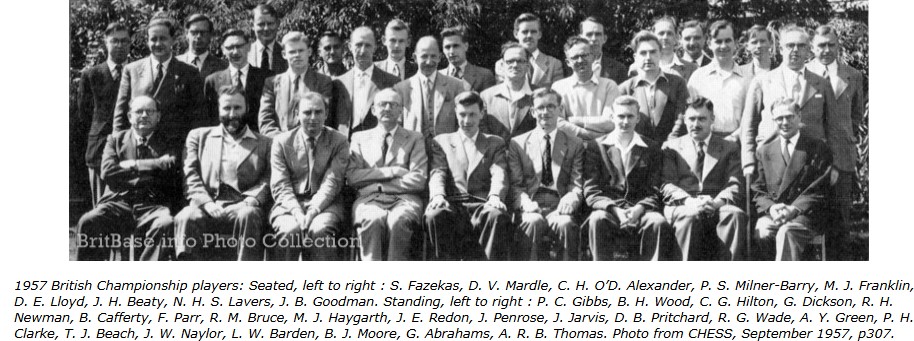

You can see him here, the bald-headed gentleman standing in the centre, with Milner-Barry and Franklin seated in front of him

1958 saw a merger between Richmond and Twickenham Chess Clubs. The result, Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club, is still thriving today. I’m not sure what part Jack played in the merger, but he must surely have been involved and given his blessing.

I’m not sure whether or not he was playing for Richmond & Twickenham in this game, a clash between the 1923 and 1962 winners of the Wernick Cup.

A few years later, Ray would treat the opening in more restrained fashion. Here, he gave Jack some difficult chances, but he was unable to take advantage.

It was only a few years later that Keene would publish his first book, Flank Openings, which I bought and eagerly devoured. It influenced my choice of opening when I faced Jack in the 1969 Richmond & Twickenham Club Championship. I called this system, a cross between a Réti and an Orangutan, the Yeti Opening.

It worked well here (I think the opening was never Jack’s strong point) and soon won a piece, but didn’t want to win hard enough against such an illustrious opponent and let him escape with a perpetual check. (If I’d won, as I should have done, it would have given me a Morphy Win number of 4, although I may well have beaten him in a casual game at some point.)

You might assume that chess players with artistic interests would play artistic chess, while those with scientific interests would prefer scientific chess. It doesn’t always work, but it was certainly true of Jack Redon. From the small sample of games here we can see someone who, at least with the white pieces, favoured dashing gambits and sacrifices, which, while not always sound, often worked over the board.

By now well into his sixties, there was inevitably some decline in his playing strength, but he continued to take part in club matches as well as serving on the club committee. In 1981 he designed a new logo for what was then the British Chess Federation.

His beloved wife Florence died in 1985, but he remained on the grading list until 1988, his clubs listed as Richmond Community Centre as well as Richmond & Twickenham. Suffering from dementia, he eventually moved to a care home in nearby Hampton Hill, where he died in 1994 at the age of 89. It appears, although there are some inconsistencies in the records, that his sister René died in Hastings in 1996, bringing an end to that branch of the Redon family.

Jack may not have been, as he believed, or wanted us to believe, the great nephew of Odilon, but I think he was something far more interesting. A man who was fortunate enough to be able spend the last fifty years of his life indulging in his favourite hobbies. He was a very good, but perhaps not brilliant, actor, playwright and artist, but he wrote plays and painted pictures not with the intention of making money but for the sheer joy of doing so. He played chess for many decades for the same reason: not a great player, but certainly a good enough player: champion of Kingston and Battersea, British Championship contender, achievements not to be taken lightly. Perhaps many of us can learn from the way Jack lived his life.

But more than that, he contributed an enormous amount to the local community in Richmond and Twickenham by founding and organising clubs and societies so that others had the opportunity to share his passions, and, through them, form friendships and enhance their lives. I believe that hobby clubs, whether chess, theatre or a thousand and one other wonderful things, are of vital importance for social cohesion, mental health and many other reasons. All of us at Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club have reason to be grateful to Jack Redon, who might justifiably be seen as the club’s founder. I hope he’s looking on benignly, delighted that, many years later, the club is still thriving.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archives

chessgames.com

BritBase

ChessBase/MegaBase

Surrey County Chess Association website

Battersea and Kingston Chess Club websites

Brian Denman

John Saunders