Back in 1975 I played in a weekend tournament celebrating the centenary of Kingston Chess Club. I’m still in touch with two of my opponents, Kevin Thurlow and Nick Faulks, today. They both post regularly on the English Chess Forum and I also see Nick at Thames Valley League matches between Richmond and Surbiton.

Kingston are in the early stages of preparing celebrations for their 150th anniversary in 2025, and asked me if I’d seen anything confirming 1875 as the year of their club’s foundation.

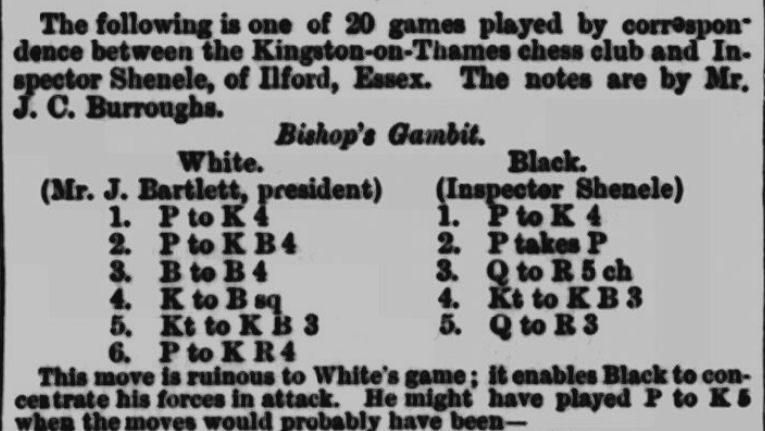

Well, there are all sorts of questions concerning, amongst other things, continuity, but I’ll leave that for another time. The Surrey Comet and Croydon Guardian and Surrey County Gazette (which carried a lot of chess news) for those years have been digitised, but searching for ‘chess Kingston’ doesn’t come up with anything. There are some earlier matches in which clubs in the area played competitions including chess along with other indoor games, but nothing obvious concerning 1875. Having said that, the OCR search facility is far from 100% accurate, so I’d have to look through all the papers for that year to check I hadn’t missed anything. The nearest I’ve found so far is this, from 1881.

We have three names here. Most important, for my Kingston friends, is that of Mr J Bartlett, President of Kingston-on-Thames chess club. I consulted the 1881 census which lists a number of J Bartletts in Kingston, but none of them seem to be obviously presidential material.

I suspect the annotator was FC (not JC) Burroughs: Francis Cooper (Frank) Burroughs (1827-1890) was a Surrey county player, a solicitor by profession. He never married and had no relations with the initials JC.

As Mr Burroughs’ initials appear to be incorrect, it’s entirely possible that Mr Bartlett’s initial was also given incorrectly. I haven’t been able to find any other chess playing Bartletts in the area as yet, but I’ll keep looking.

Here’s the game in full. Click on any move for a pop-up board.

Two weeks later, another game was published, with Bartlett again losing with the white pieces against Shenele.

We’re told that Inspector Shenele was playing by correspondence against Kingston, but there’s no indication of how many Kingston players were involved. He played two games against Barrett, but playing black in both cases. I wonder what the format was. Perhaps he played four games, two with each colour, against each of five opponents. Looking at the games, the Kingston President’s play, especially in the first game, doesn’t make a very good impression, considering he would have had plenty of time for each move.

As he was blessed with a highly unusual surname as well as a title, it wasn’t difficult to find out more about Inspector Shenele. If you’ll bear with me for straying away from Kingston, not to mention Richmond and Twickenham, his is an interesting, although sadly rather short, story.

He was born Peter Shenale on 22 March 1843 in the village of Mary Tavy, near Tavistock in Devon, the youngest child of James Shenale and Tamzin Parsons Pellew. Most of his family spelt their name in this way, but Peter preferred Shenele. He also referred to himself as PS Shenele, although I can find no record of a middle name in any official documents. The surname has its origins in Devon and Cornwall. By the 1851 census the family had moved to Gunnislake, the other side of Tavistock and just over the border in Cornwall, where James was working as a copper miner. His wife and three sons were at home: James junior was also a copper miner, while William and Peter were at school. According to Wikipedia: “The village has a history of mining although this industry is no longer active in the area. During the mining boom in Victorian times more than 7000 people were employed in the mines of the Tamar Valley. During this period Gunnislake was held in equal standing amongst the richest mining areas in Europe.” Tin and copper were the main metals mined there.

In 1861 Peter was still living there with his parents, along with a mysterious 14-year-old granddaughter, and now, like his father, mining copper. In 1867, still in the same job, he married Eliza Ann Kellow in nearby Plymouth.

At that point he (or perhaps Eliza) decided that the life of a miner wasn’t for him. If you’re a copper miner and don’t want to be a miner any more, I guess that makes you a copper, and that’s exactly what Peter did. He moved to London and joined the Metropolitan Police. By 1871 he was living in Knightsbridge with Eliza and their 5-year-old son Henry. Another son, Frederick, had died in infancy. A daughter, Ellen, would be born later that year, followed by Emma, who would also die in infancy, and William, by which time the family had moved to Chelsea.

But where did the chess come in? His background seems very different from most of the chess players we’ve encountered in this series. I’m not sure that chess was especially popular among the Devon and Cornwall mining community, but you never know. Perhaps he became interested after seeing a problem in a newspaper or magazine column.

In 1876 his name suddenly started appearing (as PS Shenele) in the Illustrated London News as a solver of chess problems.

It wasn’t long before he tried his hand at composing as well. You’ll find the problem solutions at the end of this article.

#2 Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News 11 November 1876

But at home all was not well. Peter may have been good at solving both crimes and chess problems, but his marriage had hit a problem with only one solution. On 18 April 1879 he filed for divorce, citing his wife’s adultery with a man named Charles J Reed. Perhaps Eliza had had enough of Peter spending so much time at the chess board and had sought satisfaction elsewhere. The courts found in Peter’s favour (in those days it was always considered the woman’s fault): he was awarded a decree nisi on 20 November 1879 and a final decree, along with custody of Ellen and William, on 1 June 1880.

A son, Charles Frederick Shenale, was born in Plymouth, the town where Eliza and Peter had married, on 20 August 1879 and died the following year at the age of 9 months. His parents were listed as Peter and Annie (as Eliza preferred to be called): might one assume that Charles Reed, whose first name he was given, was actually his father, and that his mother had returned to Devon to give birth?

Here’s another problem Peter composed at about this time.

#2 Preston Guardian 1880

Not content with solving and composing problems, Peter took up correspondence chess as well.

In this postal game against Irish astronomer and philosopher William Henry Stanley Monck, he concluded his attack with an attractive queen sacrifice for a smothered mate. It was published in the Illustrated London News on New Years Day 1881.

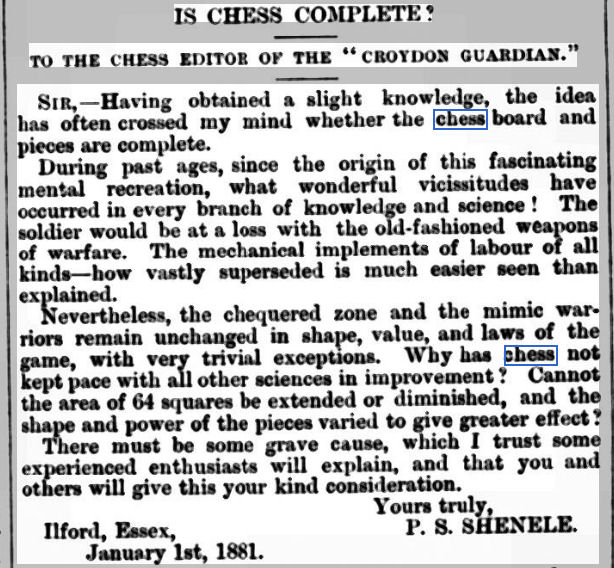

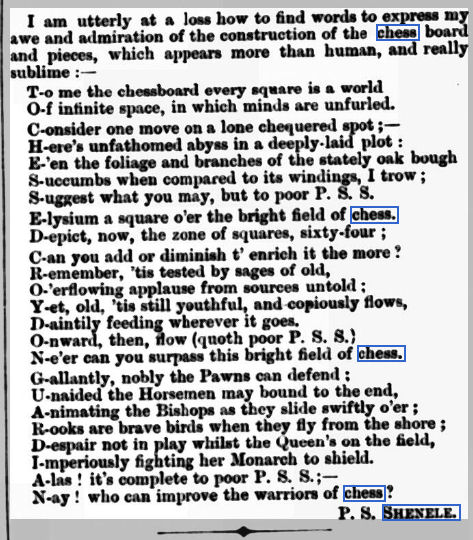

He had also taken up another unlikely interest: poetry. Also on New Years Day 1881 he wrote to the Croydon Guardian.

He also submitted this poem which, in the fashion of the day, is an acrostic. The first letter of each line spells out a message.

By this time he’d been promoted to the rank of Inspector, and had moved out, as you can see above, to Ilford, where, when the 1881 census enumerator called, he was living with young William. Emma wasn’t at home: she might, I suppose, have been away at school. Henry was living in the Devonshire Club in Piccadilly, working as a page boy.

It was about this time, also that he played the correspondence match against Kingston-on-Thames Chess Club. I’ve yet to discover exactly how this came about: quite possibly via his connection with the Croydon Guardian, the main source for Surrey chess news at the time.

Chess and policing weren’t the only things on Peter’s mind in 1881. On 31 January 1882 he married a local girl, Sarah Jane Seabrook, who, it seems, was pregnant with their daughter Ethel Emily, whose birth was registered in the first quarter of that year. This didn’t stop his chess activities: he entered a correspondence tournament run by the Croydon Guardian.

This correspondence game was played in 1893 against Horace Fabian Cheshire. Both players demonstrated knowledge of contemporary Evans Gambit theory, but our hero went wrong shortly after leaving the book. Thanks to Brian Denman for providing this game, which was published in the Southern Weekly News (8 Sep 1883).

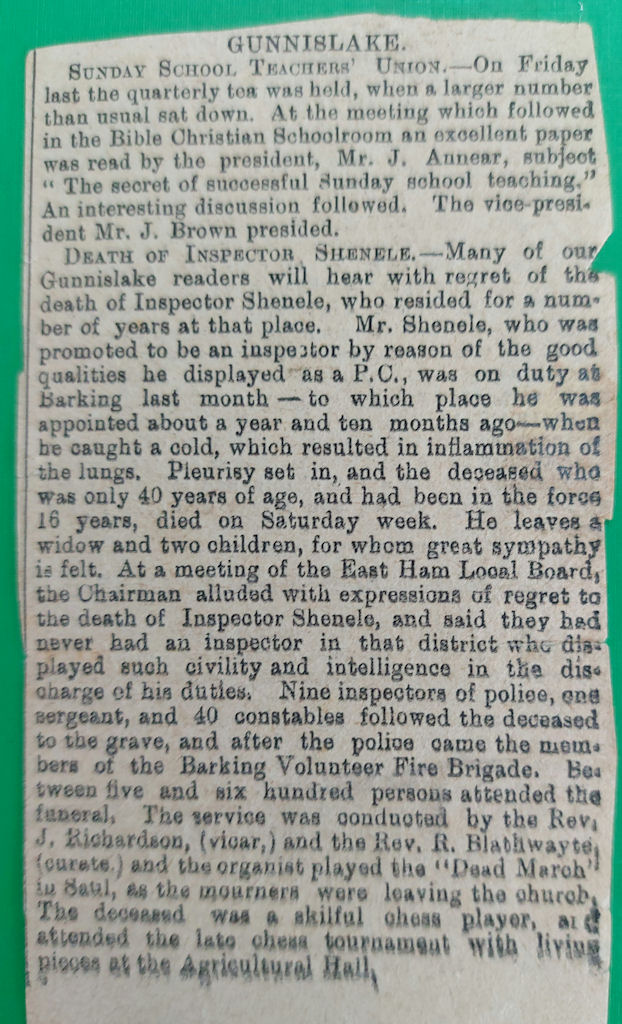

But then, in the same year, tragedy struck. A son, named Albert, was born in September, but died 5 days later: the third child he’d lost in infancy. He then caught a cold, which developed into pleurisy. On 10 November 1883, at the age of only 40, Peter Shenele died after a short illness. A local paper back in Cornwall published this tribute.

You can see some parallels, can’t you, with James Money Kyrle Lupton, from a later generation. Both were problem solvers and composers who liked to see their name in print, and both were also police officers in London. But while James, from a privileged background, only became a constable, Peter, a man of relatively humble origins, became an inspector.

As always, I’m sure you want to know what happened next. Eliza Ann (Annie) remarried in 1893, not to Charles Reed, but to a widower named James Trump (no relation to Donald), a plasterer by trade. Ellen sadly died in 1894. Sarah Jane moved in with her brother Frederick, like their father a publican, and the family later emigrated to New York. It’s not clear what happened to Ethel. There’s a burial record for Ethel Emily Seabrook in Newham, East London in 1898, which might have been her.

Peter’s younger surviving son, William, joined the Royal Navy, then became a clerical officer in the Civil Service, marrying but not apparently having any children, and living on until 1968.

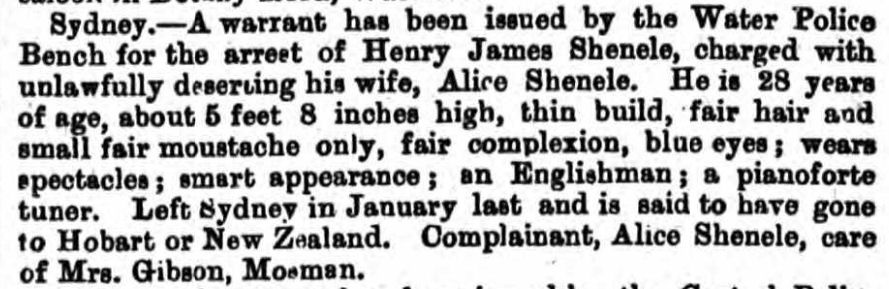

Peter’s oldest son, Henry, emigrated to Australia in 1885. In 1891 he married Alice Huxley, and, in the same year, a son, George Leslie Shenele, was born. But then things started to go wrong. In 1895 a warrant was issued for his arrest.

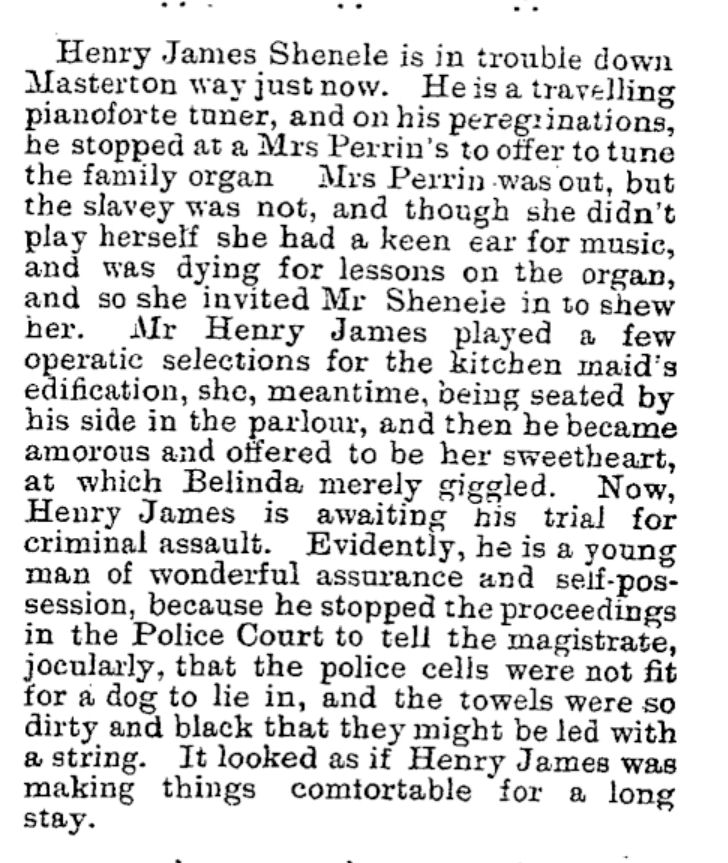

He did indeed go to New Zealand, to Masterton, near Wellington, where, in April that year, a month before the above announcement, he was put on trial for rape. What exactly happened between Henry James and Belinda the slavey I don’t know. Offering to tune the family organ indeed!

It was later reported that the Grand Jury threw out the bill. As always in those days (and you might think things haven’t changed much) he got away with it. (Thanks to Gerard Killoran for this information)

After that the trail goes cold. What happened to the police inspector’s son, the seemingly mild-mannered, bespectacled piano tuner? I’d imagine he changed his name, but no one seems to know.

George Leslie settled in Campsie, a suburb of Sydney, married, had two children, Ilma and Cyril, but his wife died young. He worked on the railways, eventually becoming an inspector, the same rank, but not the same profession, as his grandfather. Guess what happened to Cyril. He followed (was he aware?) in his great grandfather’s footsteps, becoming a policeman, rising to the rank of (at least) Detective Sergeant.

And that is the story of Peter Shenele, copper miner, police inspector, chess problem solver, composer and correspondence player, who provided a random distraction from my investigations of chess players of Richmond, Twickenham and surrounding areas. I’ll try to find out more about the early history of chess clubs in Kingston: if I come across anything interesting I’ll let you know.

Sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

MESON chess problem database

Brian Denman/Hastings & St Leonards Chess Club website

Gerard Killoran/Papers Past (New Zealand)

Problem 1 solution:

1. Qg1! threatening Nfd4# or Nh4#. 1… Qg3/Qg2/Qxg1 2. Bd7# 1… exf3/e3 2. Bc2#

Problem 2 solution:

1. Qc6! threatening N mates on g6 as well as two queen mates. 1… Rxc6 2. Nf7# 1… Re6 2. Qxe6#