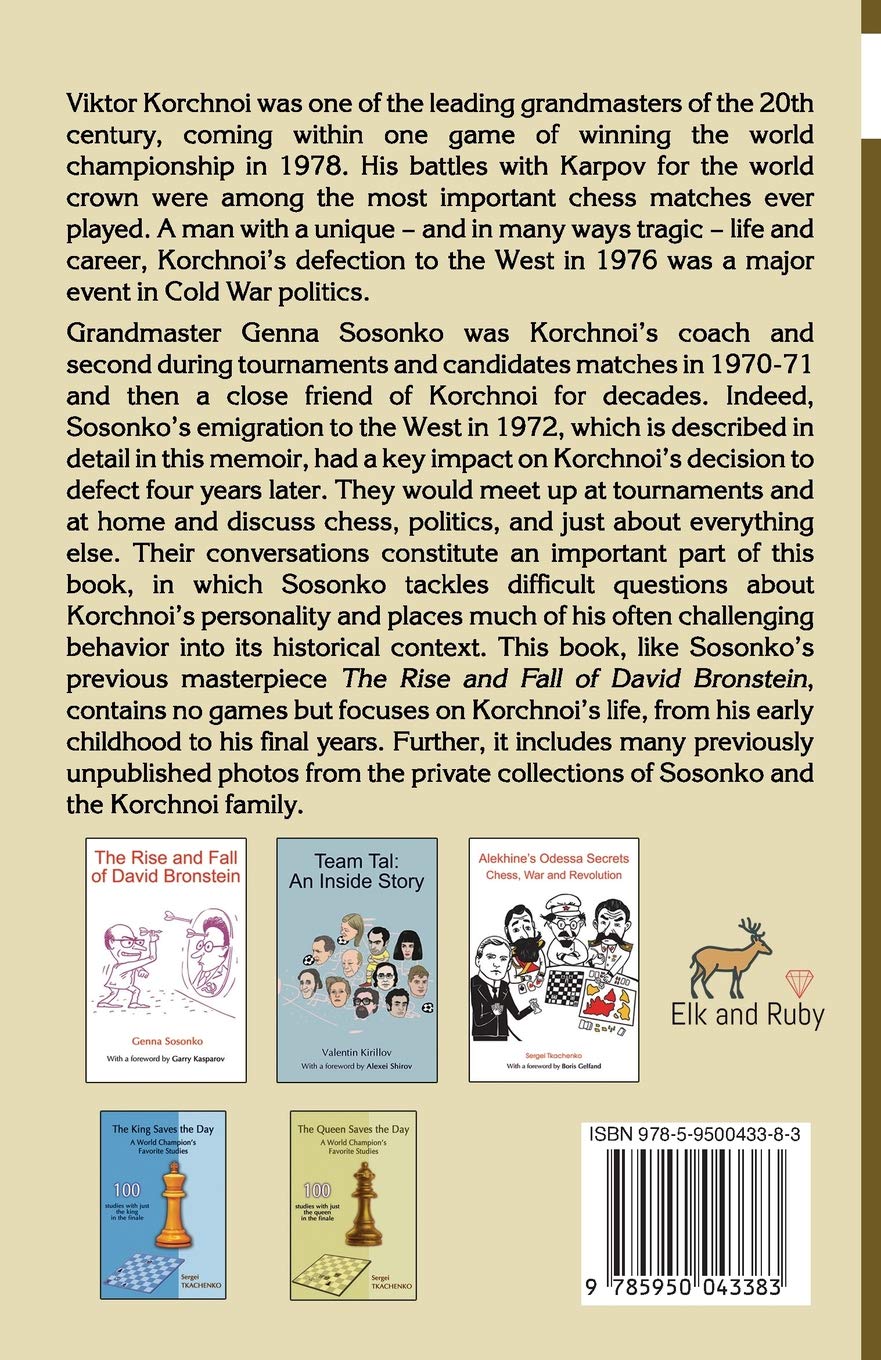

From the rear cover :

“A winning streak in chess, says Cyrus Lakdawala, is a lot more than just the sum of its games. In this book he examines what it means when everything clicks, when champions become unstoppable and demolish opponents. What does it mean to be “in the zone”? What causes these sweeps, what sparks them and what keeps them going? And why did they come to an end?

Lakdawala takes you on a trip through chess history looking at peak performances of some of the greatest players who ever lived: Morphy, Steinitz, Pillsbury, Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Botvinnik, Fischer, Tal, Kasparov, Karpov, Caruana and Carlsen. They all had very different playing styles, yet at a certain point in their rich careers they all entered the zone and simply wiped out the best players in the world.

In the Zone explains the games of the greatest players during their greatest triumphs. As you study and enjoy these immortal performances you will improve your ability to overpower your opponents. You will understand how great moves originate and you will be inspired to become more productive and creative. In the Zone may bring you closer to that special place yourself: the zone.

“Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master and a former American Open Champion. He has been teaching chess for four decades and is a prolific and widely read author. His Chess for Hawks won the Best Instructional Book Award of the Chess Journalists of America (CJA). Other much acclaimed books of his are How Ulf Beats Black, Clinch It! and Winning Ugly in Chess.”

Most of you will be aware of Cyrus Lakdawala’s style of writing. You’ll know that he polarises opinions: some love his books while others hate them. From what I’d read, I’d always thought his books weren’t for me: I’ve never bought one, although a friend gave me a copy of his recent book on the French Defence last year.

So I could write a very brief review. If you’re a Lakdawala fan, and there are many around, you’ll certainly want to read this book. If you’re not a fan you should stay well clear.

I guess you’re expecting me to say more, and there’s quite a lot to say.

This is an excellent and original idea for a book. We meet some of the greatest players from Morphy onwards and look at their peak performances. You get a broad view of chess history over the past 160 or so years, witness how chess knowledge has accumulated and how styles have changed over that time. You also get to see a lot of great chess, with some very (too?) familiar games being contextualised by their juxtaposition with less familiar games played by the same player in the same event. It might even inspire you to get ‘into the zone’ yourself in your next tournament, whenever that might be.

The chapters feature:

- Morphy 1st American Chess Congress 1857

- Steinitz match v Blackburne 1876

- Pillsbury Hastings 1895

- Lasker New York 1924

- Capablanca New York 1927

- Alekhine Bled 1931

- Botvinnik World Championship Tournament 1948

- Fischer 1963/4 US Championship

- Tal Riga 1979

- Kasparov Tilburg 1989

- Karpov Linares 1994

- Caruana Sinquefield Cup 2014

- Carlsen Grenke Chess Classic 2019

In total there are 120 games: some complete, some just the conclusion, almost always won by the heroes of each chapter, all annotated in Lakdawala’s trademark lively style. As a highly experienced author and teacher, he knows just how to get the balance right between words and variations, and has used a modern engine to check the analysis. You’ll find lots of Exercises (for you to solve), Principles (to help you improve) and Moments of Contemplation (to think about an interesting position).

This has always been one of the author’s favourite games, but you’ll have to buy the book to read the annotations.

Cyrus Lakdawala is clearly some sort of crazy (to use one of his favourite words) genius. I’m in awe of his productivity, his work ethic, his imagination, his general knowledge, his wide range of references. It’s well worth listening to this interview on Ben Johnson’s excellent Perpetual Chess Podcast in which he explains how and why his brain doesn’t work like anyone else’s.

But – and, for me, at any rate, it’s a very big but, he comes across as a writer who rushes to complete the book without double checking everything, and who lacks any awareness as to whether or not his light-hearted asides and fanciful analogies are helpful or appropriate. He’s also, by no means uniquely among chess authors, a lot stronger writing about contemporary players than about historical figures.

There are various mistakes which might not be important, but are unnecessary and, at least for this reader, annoying. Blackburne’s first names appear at various points as ‘Joseph Henry’, ‘Henry Joseph’ and ‘Henry’. In the heading of a game between Lasker and Marshall, Emanuel’s name becomes Edward, confusing because they both played at New York 1924. In Fischer’s Famous Game against Robert Byrne the heading is correct, but a few lines further down Robert turns into his brother Donald, who, again, was playing in the same event. These errors should really have been picked up by the editor or proofreader.

Then there’s the hyperbole. “Paulsen routinely took eight full hours to make his moves.” “Marshall’s normal temperament was that of a belching, gurgling volcano…” “Alekhine destroyed every stick of furniture in his hotel room, in a near psychotic rage.” Sentences like this would induce a near psychotic rage in several chess historians I could mention.

Most seriously, many of the more frivolous asides might be considered by some to be in poor taste. We have throwaway references to Jeffrey Epstein, Michael Jackson and, on several occasions, the British Royal Family. Then, what do you make of this? “Blunders like this one are a first-rate reason why no sane person should voluntarily take up chess as a hobby. It’s basically like marrying a spouse who beats you up on a daily basis.” Or this, after mentioning that Raymond Weinstein has been in a psychiatric hospital since 1964? “Thanks a lot, Ray! This does a lot to help eradicate the stereotype that we chess players are just a touch crazy!” You might think domestic abuse and mental illness are inappropriate subjects for levity in a book of this nature.

Now I don’t want to knock the author, any more than I’d knock Reinfeld and Chernev. I’m all in favour of people whose brains work in a different way. I’m all in favour of teachers and writers whose communication skills enable them to share their passion and enthusiasm for chess. There’s always a place within the chess world for authors who can bring our game to a wider audience, and Lakdawala’s colourful writing style, although not for chess and linguistic purists like me, offers a lot of pleasure to a lot of people.

On the other hand, he can easily go over the top, and perhaps it’s the responsibility of his publishers to be more proactive. With a pair of scissors to remove the pointless and sometimes tasteless analogies and a red pen to correct the mistakes and typos this could have been an excellent and – 50 pages shorter – addition to chess literature. Nevertheless, if you’ve enjoyed Lakdawala’s previous volumes and can live with the faults, you’ll like, and perhaps learn a lot from, this book.

Caveat Emptor.

Richard James, Twickenham ?th September 2020

Book Details :

- Paperback : 400 pages

- Publisher: New in Chess (7 Aug. 2020)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 905691877X

- ISBN-13: 978-9056918774

- Product Dimensions: 17.15 x 1.91 x 23.5 cm

Official web site of New in Chess