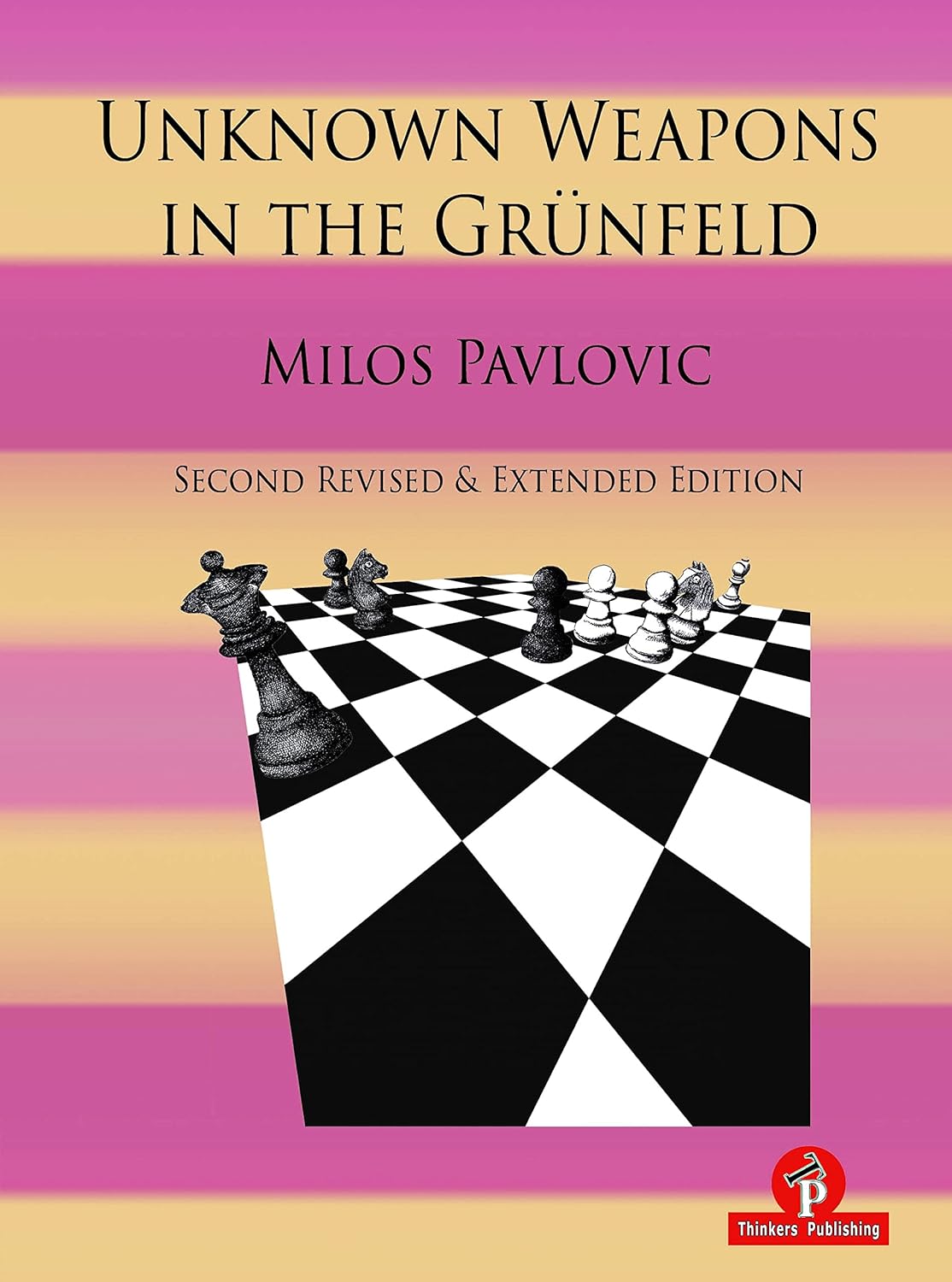

I’ve long been intrigued by this match played on board a liner in 1930.

There’s much to be written about the Imperial Club, which played an important part in many aspects of London chess between its foundation in 1911 and the outbreak of the Second World War. It provided a venue for social chess for both Londoners and those from other parts of the British Empire who happened to be passing through, but it was also far more than that. The club was founded by the extraordinary Mrs Arthur Rawson (Ella Frances Bremner): I’ll tell her story, and more of the club’s story in future Minor Pieces.

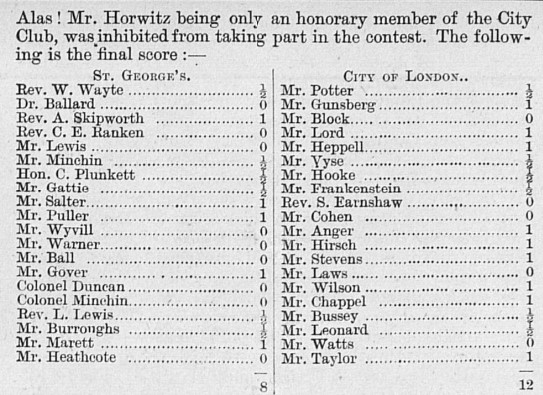

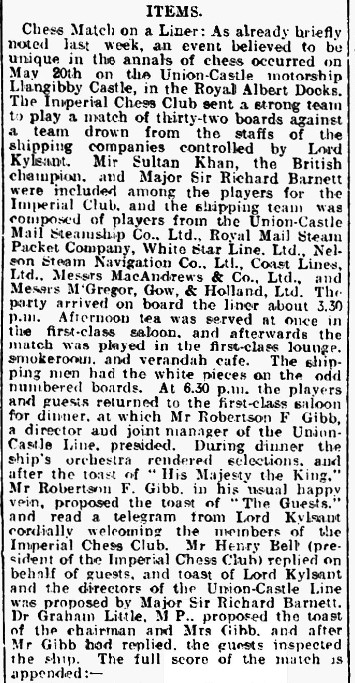

The list of their players in this match provides a snapshot of their membership, and, more generally, tells us something of the social status of chess in the inter-war years.

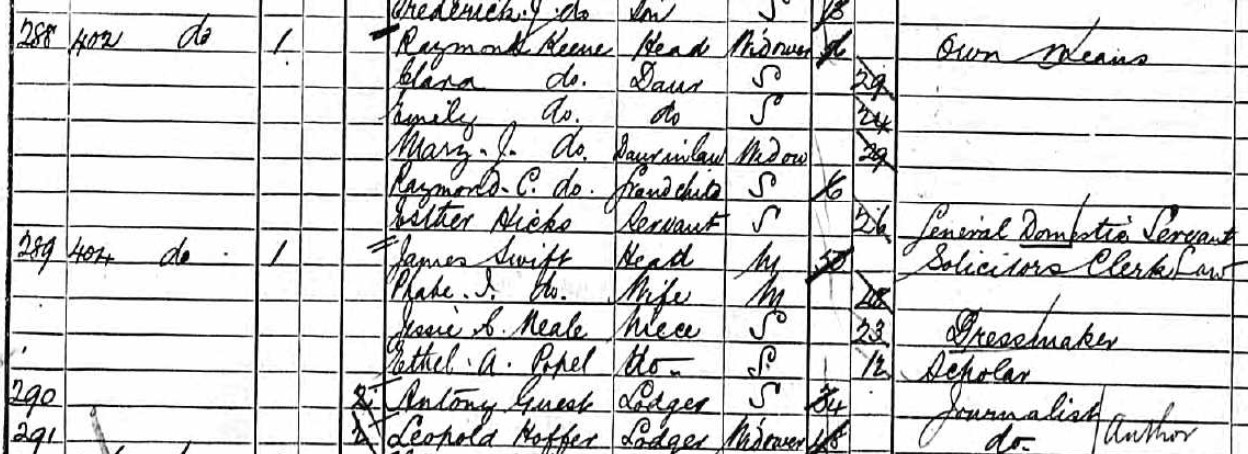

Board 1: Sultan Khan (1903-66: Mir, along with Malik, is an erroneous honorific which shouldn’t be considered part of his name) needs no introduction. In this match he could only draw with the little-known W Veitch, although it’s quite likely the result was diplomatic.

Only seven months later he won a Famous Game against none other than Capablanca. For this and all games in this article, click on any move for a pop-up window.

Here he is, on the left, playing against his patron (board 18 in this match).

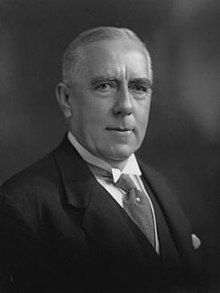

Board 2: Major Sir Richard Whieldon Barnett (1863-1930) – Irish barrister, sportsman (shooting), volunteer officer and freemason, Irish chess champion 1886-89, Conservative and Unionist MP 1916-29. Most of his constituency now comes under Holborn and St Pancras, represented today by Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer. He died just a few months later, on 30 October 1930, following an operation. You can read an extensive obituary published by the BCM here (scroll down to ‘Barnett’).

Here’s his game from this match, which also looks like a diplomatic draw as he was a pawn up with a probably winning advantage in the final position.

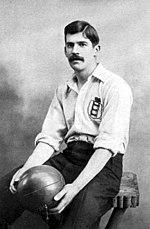

Board 3: Charles Wreford-Brown (1866-1951) – amateur footballer (one of the best of his day, captaining his national team) and cricketer. He didn’t play a lot of competitive chess, but what he did was at a high standard, taking part in the unofficial chess olympiad of 1924 (he lost to Marcel Duchamp in an unlikely encounter between two very different celebrities) and playing in the 1933 British Championship, where he unfortunately had to withdraw for health reasons having won and drawn his first two games. A few years ago I met one of his cousins in a school chess club and was able to show him this game.

Here he is, wearing his England football shirt.

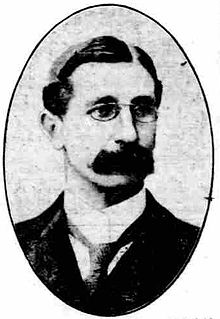

Board 4: Vickerman Henzell Rutherford (1860-1934), politician and doctor. The Imperial Chess Club attracted many politicians, mostly from the Conservative Party, but the splendidly named VH Rutherford was an exception, representing the Liberal Party as an MP before switching allegiance to the Labour Party. The current incarnation of his Brentford constituency, now Brentford and Isleworth, is currently represented by Ruth Cadbury, very distantly related to the Secretary of Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club.

In 1925 Barnett and Rutherford played in the two parallel sections of the First Class tournament at the British Championships in Stratford, both scoring 6/11, suggesting that they were both strong club standard players. EdoChess gives Rutherford’s rating at the time as about 2000. Judge for yourself from this game.

Board 5: Colonel E Marinas: not certain about his identity but there was a Spanish (?) naval officer named Eugenio Marinas around at the time so it might possibly have been him.

Board 6: Edward Harry Church (1867-1947), a pharmaceutical chemist from Cambridge, was a leading light in local chess circles, being President of his club for many years and would later (1938-39) be elected President of the Southern Counties Chess Union. He must have had occasion to spend time in London as well.

Board 7: JG Bennett. I’m uncertain as to the identity of this player. There were two JG Bennetts loosely involved in chess: James George Bennett (1866-1952) was a journalist from Grantham in Lincolnshire: quite a long way from London, but he could have been there on business. There was also a JG Bennett involved in administration and occasionally playing in Kent, perhaps in the Canterbury area, but I haven’t been able to identify him further.

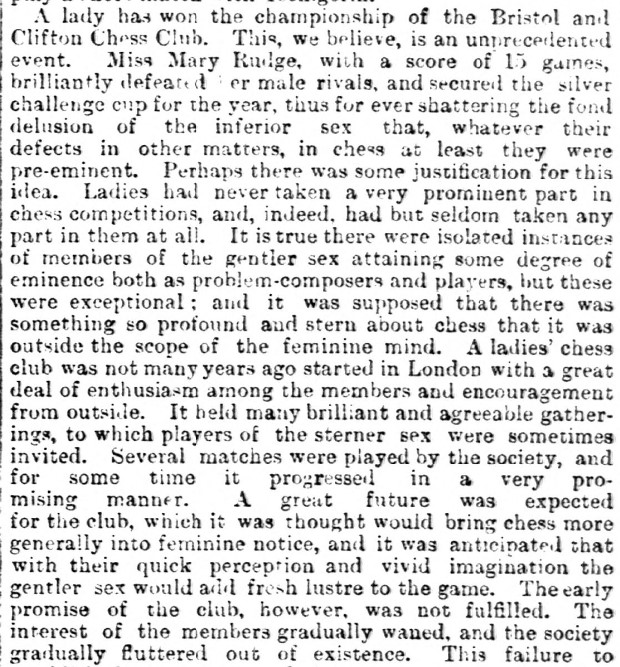

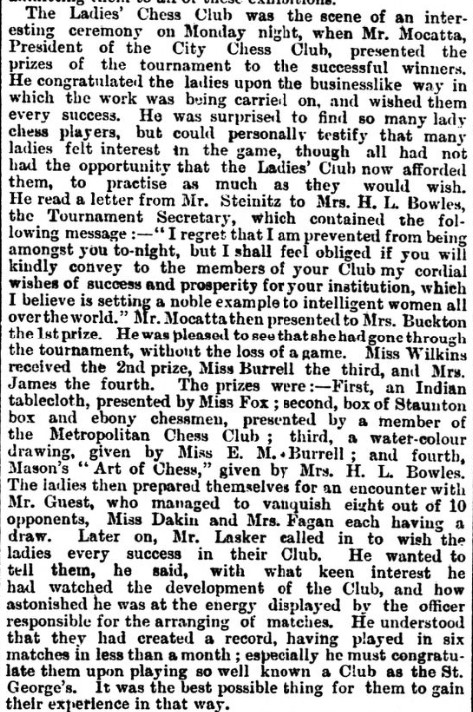

Board 8: Miss Kate (Catherine) Belinda Finn (1864-1932) had been active in Ladies’ chess circles, being a founder member of the Ladies’ Chess Club in 1895, as well as winning the British Ladies’ Championship in 1904 and 1905. For further information see John Saunders here.

She’s on the right here, playing in the 1905 British Ladies Championship.

Board 9: this must be John Goodrich Wemyss Woods (1852-1944), a retired schoolmaster (second master and mathematics teacher at Gresham’s School, Norfolk) and amateur artist. The only other chess reference I can find for him is helping to provide some annotations to a game played by a fellow Imperial member some years earlier.

Here’s one of his paintings.

Board 10: Hon. Arthur James Beresford Lowther (1888-1967) was a barrister who served in the First World War (see here), After the war he became Assistant Commissioner for Kenya (1918-20) and later Aide-de-Camp to the Governor of Southern Rhodesia in 1923. On his return to England he took up competitive chess, finishing runner-up in the 2nd Class tournament in the 1927 British Championships.

Board 11: Miss Alice Elizabeth Hooke (1862-1942), who has featured in earlier Minor Pieces here and here. She was a chess player and organiser, sharing first place in the 1930 and 1932 British Ladies Championships.

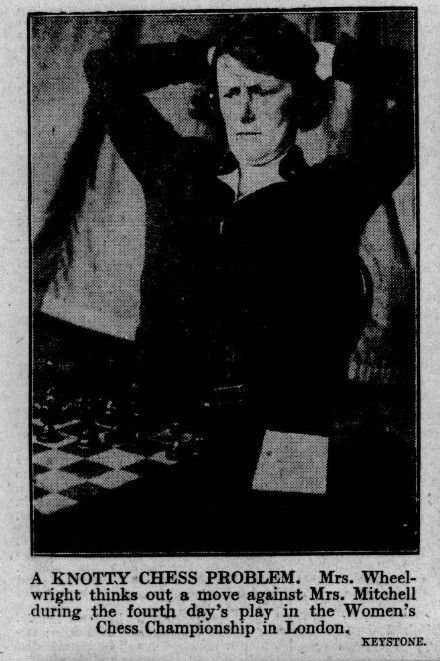

Board 12: Mrs Amy Eleanor Wheelwright, née Benskin (1890-1980), another of the strongest lady players of the period, sharing first place in the 1931 British Ladies Championship, and taking the runner-up spot in 1933. Here she lost to the tournament winner, a member of Sir Umar Hayat Khan’s entourage.

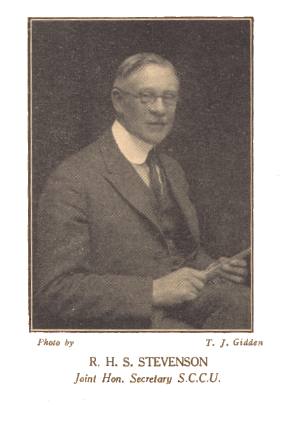

Board 13: Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson (1878-1943), later the husband of Vera Menchik and Hon. Secretary of the BCF, was one of the most important figures in British chess in the inter-war years as an administrator and also a promoter of women’s chess. He was also a regular competitive player, winning the Kent championship in 1919: a result which probably flattered him as I suspect the stronger players in the county didn’t take part.

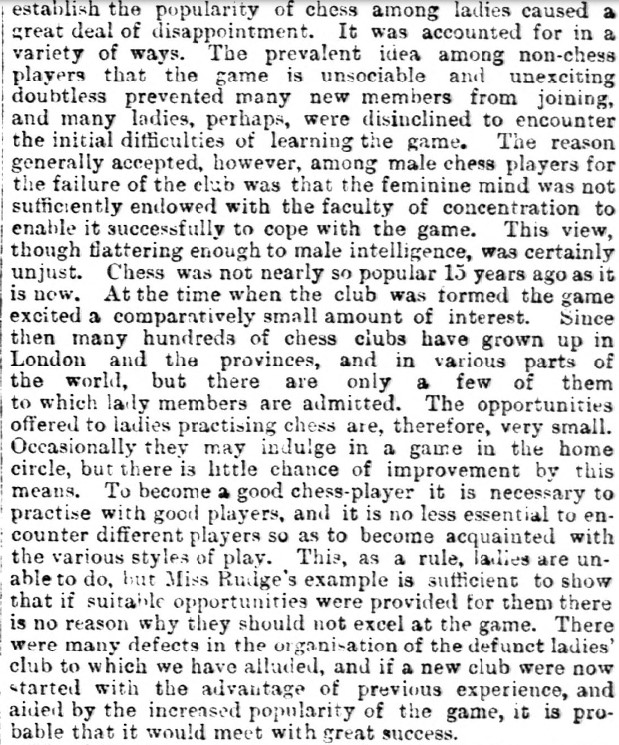

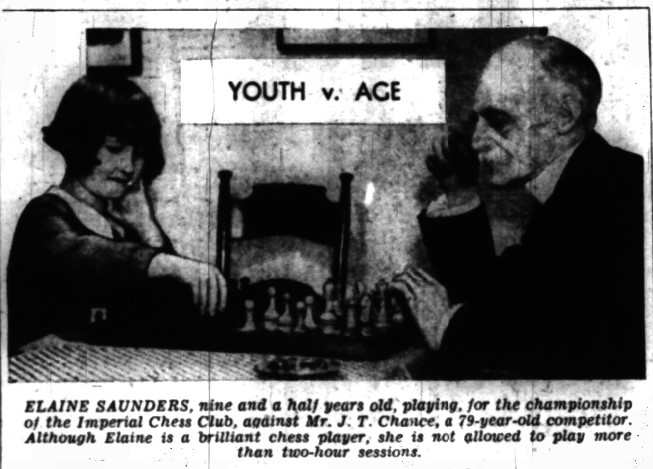

Board 14: James Frederick Chance (1856-1938) came from a prominent family of glass manufacturers in the Black Country but later devoted his life to the study of history. In 1911 he was in Offchurch, near Leamington Spa, visiting his sister Eleanor and her husband, a retired clergyman named William Bedford. They were living next door to the vicarage where James Agar-Ellis employed my great aunt Ada Padbury as a cook. He was a long-standing member of the Imperial Chess Club, serving as president from 1934 until his death. His obituary in the BCM described him as being a chess player of medium strength.

Here he is, in 1935, playing the young Elaine Saunders.

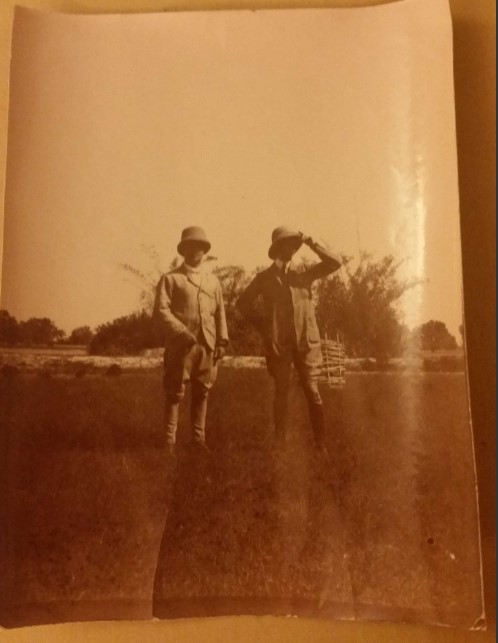

Board 15: Julian Veitch Jameson (1880-1932) came from a family with Irish and Scottish connections as well as links to both India and Kenya. In 1891 he was living in Bowden Hall, Great Bowden, near Market Harborough, where he might, I suppose, have met some of my father’s relations. He later worked as an indigo planter in India. His middle name came from his grandmother Mary Jane Veitch, so he may have been distantly related to Sultan Khan’s opponent. He was active in chess circles for the last few years of his life, scoring 50% in the 2nd Class B section at the 1929 British Championship in Ramsgate, when he was living in Chalfont St Giles, but later moving to Folkestone, where he drew with Yates in a 1931 simul. His son Thomas played cricket for Hampshire.

This photograph from an online family tree shows Julian with a friend.

Board 16: Miss Mary Ann Eliza Andrews (1863-1954) was born on the island of Jersey, but her family later moved to Brighton. Her brother, William Richard Andrews, was a prominent Sussex player. She later worked as a schoolmistress. In 1921 she was living in New Cross, South London, in the same road as Jack Redon and his family, but teaching at Halley Road School in Limehouse, north of the Thames. She only seems to have taken up competitive chess on her retirement, playing in the British Ladies Championship in 1923, 1926, and in 8 consecutive years from 1928 to 1935. Her best scores were 8/11 in 1934, and 7/11 in 1930, 1931 and 1932. In 1928 she shared first place in the 2nd Class B section of the West of England Championships (well ahead of Arthur Lowther), but lost this game to the other joint winner, who was killed by a Japanese sniper in Burma in 1944.

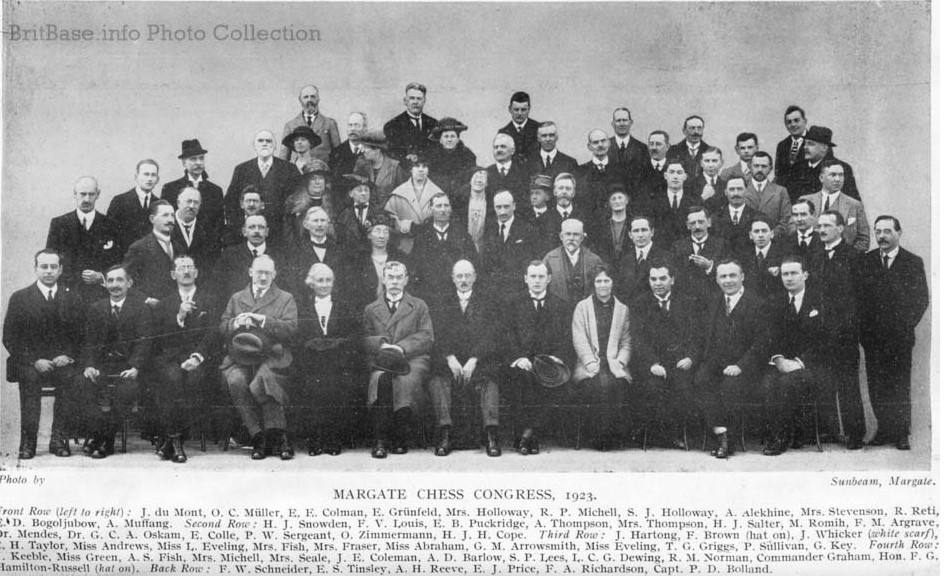

Miss Andrews is the lady wearing what looks like a fur stole centre left, with Lilly Eveling next to her. Lilly’s sister Clara is further along the same row towards the right. If you visit BritBase here you can hover over the faces to identify the names.

Board 17: FH George. I have no information about this player. Seemingly not connected to TH George of Ilford, who would have been on a much higher board. There was a player of that age who lost all his games in a junior tournament in Ramsgate in 1929. There was a Frank Harold George from London (1870-1940) who was, intriguingly, a Comedian in 1911, and working for Harrods as a Clerk in the Counting House in 1921. This might, I suppose, have been him.

Board 18: Major General Nawab Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana (1874-1944) was a soldier of the Indian Empire, one of the largest landholders in the Punjab, and an elected member of the Council of State of India, who had brought Sultan Khan to London and promoted his chess career. He must also have been a reasonably strong player himself.

Board 19: Mrs Latham is something of a mystery. She played in the 1907 Ostend Ladies tournament, then joined the Ladies club in London, moving on, like many of her clubmates, to the Imperial Chess Club, where she played at least up to this match. She can be seen in a photograph of a reception held for Alekhine in 1932, but she was never awarded even an initial, let alone a first name. Can anyone out there help identify her?

Mrs Latham is the lady seated on the left, with Mrs Arthur Rawson next to her. You’ll then spot Vera Menchik and Alekhine, with Sultan Khan on the floor on the right. Other participants on the liner included RHS Stevenson (2nd left top row), C Wreford-Brown (4th left top row), next to him Sir Ernest Graham-Little, and then Sir Umar Hayat Khan. Edward Winter provides the full list of names here (you’ll have to scroll down a bit). Note that A Rutherford is not related to VH Rutherford.

Board 20: Mrs M Healey is another mystery. She played in some tournaments in the late 1920s when she was living in South Croydon, and again in the late 1930s by which time she had moved to Hastings. She won a prize at Hastings in 1938 for the best score by a lady in the Second Class section. It’s not clear whether M was her or her husband’s initial.

Board 21: Arthur Newton Streatfeild (1859-1956) was secretary of the Carlton Club for many years. He doesn’t appear to have been a competitive chess player. A member of a distinguished family (note the spelling) who would therefore have had a family connection with his teammate on Board 13.

Board 22: most likely to be Harry Norman Hunter (1883-1966?), a music salesman/publisher originally from Sunderland. In 1921 he was working for Francis, Day & Hunter: the Hunter comes from the music hall composer and performer Harry Hunter, whose real name was William Henry Jennings, and seems to have had no connection with Harry Norman Hunter. I can’t find any other record of him playing chess.

Board 23: Miss Lilly Eveling (1867-1951) came from a prosperous family of drapers in Kent. She played competitively from 1913 up to the second world war, but with little success, scoring only 1/11 in both her appearances in the British Ladies Championship, in 1930 and 1931. Her sister Clara was also a chess player.

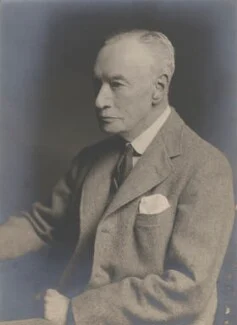

Board 24: Henry Bell (1858-1935) was a banker and financier, rising to become general manager of Lloyds Bank, and also a Director until his retirement in 1924. In that year he unsuccessfully stood for parliament representing the Liberal Party in a by-election for the City of London constituency. He was also the President of the Imperial Chess Club for several years.

Board 25: Sir Thomas William Richardson (1865-1947) was a former civil servant and High Court judge in India, who, on returning to England, was very much involved with promoting the development of municipal housing in Fulham.

Board 26: Mrs Fitzgerald. The full name and dates of this player are currently unknown to me.

Board 27: likely to be Miss Marion Isabella McCombie (1866-1936), the daughter of a quill merchant. I have no further information about her chess.

Board 28: Mrs Yuill The full name and dates of this player are again currently unknown to me.

Board 29: Mrs Ella (Ellen on her birth record) Frances Rawson (née Bremner) (1856-1942) was the founder of the Imperial Chess Club and a promoter of chess for women and girls. Born in Glasgow, she emigrated to New Zealand where she married Arthur Rawson. Her husband died in 1894, and in about 1909 she moved to London, where she founded the Imperial Chess Club. I’ll write more about this in a future Minor Piece. Although purely a social player herself she was a very important figure in London chess in the inter-war years.

Board 30: Florence Mary (Miles-)Bailey (née Hobson) (1866-1952), daughter of a master builder and widow of a stockbroker, who achieved some fame by playing chess on long-distance aeroplane flights (see here). Although some of her games took place at a high level, her standard of play was probably at a relatively low level.

Board 31: Sir Ernest Gordon Graham Graham-Little (1867-1950) was a dermatologist and Independent MP for London University from 1924 to 1950. If he’d stood for election there in 1922 or 1923 he’d have faced the novelist and chess enthusiast HG Wells, who unsuccessfully represented the Labour Party. Although not a strong player himself, Sir Ernest was a great patron of chess who rarely missed an opportunity to support his favourite game.

Board 32: Hon Mildred Dorothea Gibbs (1876-1961), known as Minnie in her family, was a daughter of the 2nd Baron Aldenham, a Conservative politician from a famous banking family.

From a family website: Quartermaster of London Voluntary Aid Detachment No. 30 of the British Red Cross Society, 1910; commandant of No. 116, 1913. Served with Bulgaria Red Cross Society in Kirk Kilisse 1912-13 (decorated by the Queen of Bulgaria). In the Great War, amongst other V.A.D. services in London, was in 1915 successively a Nurse at Westminster V.A.D. Hospital, in charge of a Belgian Refugee Convalescent Hostel, and on Air Raid duty; and, from October 1915 to November 1918, Head of the Posting Department of County of London Branch of the Bulgaria Red Cross Society. Attached to the Westminster Division of the B.R.C.S. October 1919, sometime temporary secretary and vice-chairman, chairman 1926-8. Resigned V.A.D. 1929. ‘Member’ 1918, ‘Officer’ 1919, of the Order of the British Empire. Member of the Church of England National Assembly from 1925.

She’s the girl on the right in this charming family photograph.

You’ll immediately notice a few things about the Imperial team. Most obviously, there are 13 ladies amongst the 32 players, although mostly on the lower boards. They’re all from upper middle class or even minor aristocratic backgrounds. They’re mostly older, with many born back in the 1850s and 1860s. Apart from Sultan Khan, the youngest was Amy Wheelwright, born in 1890.

And here they all are: the players from both teams: you can see a larger version, thanks to Edward Winter, here.

I can add a little about the top three players in Lord Kylsant’s team.

Board 1: William Veitch (1877-1957) was born in Kincardineshire in the East of Scotland, which is where his surname originates. His family moved down to Hampshire, where he played for Southampton and Hampshire in the years before the First World Wat, then moving to the Lewisham area of London, where, in the 1939 Register, he was described as a Ship Owner’s Clerk. Playing on a high board for his club and a lower board for his county, he was a decent above average club standard player.

Board 2: Leslie Alec Seymour Howell (1900-1959: Alec Leslie on his birth record) was a shipping accounts clerk from the Edmonton/Tottenham area of North London, working for the Royal Mail Line. I have no other record of him playing competitive chess, but he was clearly a decent player. Here he is, pictured with his wife, Hilda.

Board 3: David(?) Storrar. Another rather unusual surname, again from the East of Scotland, so it shouldn’t be too hard to track him down. Here we hit a problem. D Storrar from Plaistow was solving chess problems in the Daily News in 1904. There was a D Storrar living in Islington in 1911, born in Perth in 1889, but he worked in banking, not in shipping. There was also a David Storrar on the electoral roll in East Ham (adjacent to Plaistow but some way from Islington) in 1913 and 1915. These three may be all the same person, or two or three different people. The 1911 Islington Storrar is apparently the same person as the David Duncan Storrar who married in Westminster in 1933, and died in Kampala in 1944, having worked for the National Bank of India. We can also pick him up in Aberfeldy, Perthshire, in the Scottish 1921 census, again described as a banker. If this is our man he must have been a ringer. Perhaps the East London 1904/1913/1915 David Storrar is a different, chess-playing, shipping person but I can’t find him on any census records or family trees. Who knows?

As a result of my problems with Mr Storrar, I decided not to go any further down Lord Kylsant’s list. None of the names looks familiar: I presume that, apart from Veitch, who had played competitively 20 years earlier, they were purely social players.

But what of Lord Kylsant himself. I’m sure you want to know more.

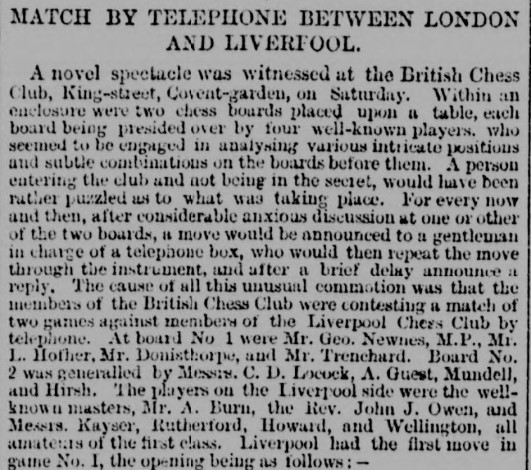

He was Owen Cosby Philipps (1863-1937), who had been a Liberal MP from 1906 to 1910, and then, switching allegiance, a Conservative MP between 1916 and 1922. His family also ran a shipping company, and he became involved with the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, of which he became managing director in 1902. They gradually took control of various other shipping companies, including the Union-Castle Line, whose ship the Llangibby Castle, which had only been launched the previous year, served as the venue for this match.

All was not well with the company, though. In 1928 investigations began looking into financial irregularities, and this match may well have been part of a charm offensive to garner favourable publicity before the trial took place. The nub of the issue seems to have been that they were accused of misleading potential investors about the company’s financial health.

When the trial took place in 1931 Kylsant, despite the efforts of his defence team led by Imperial Chess Club Vice-President Sir John Simon, was found guilty on one charge, and sentenced to a year’s imprisonment, of which he served 10 months in Wormwood Scrubs. Large companies these days get away with far worse crimes.

If you have any corrections or further information about any of the players in this match, especially about those I’ve been unable to identify, please let me know.

There’s a lot more to write about the Imperial Chess Club: there will be further posts going backwards and forwards in time and introducing you to more of their members.

But first, taking a different view of the social function of chess in the inter-war years, there’s a significant anniversary to celebrate later this month.

Join me soon for another Minor Piece.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

BritBase/John Saunders

Chess Notes/Edward Winter

British Chess Magazine

chessgames.com

ChessBase 18/Stockfish 17

Gibbs, Jameson, Howell and Hooke websites/family trees

Kingston Chess Club website

Other sources linked to above