Remembering Reverend William Wayte (04-ix-1829 03-v-1898)

Here is his Wikipedia entry

See article by JS Hilbert in the June 2012 BCM, page 296

Remembering Reverend William Wayte (04-ix-1829 03-v-1898)

Here is his Wikipedia entry

See article by JS Hilbert in the June 2012 BCM, page 296

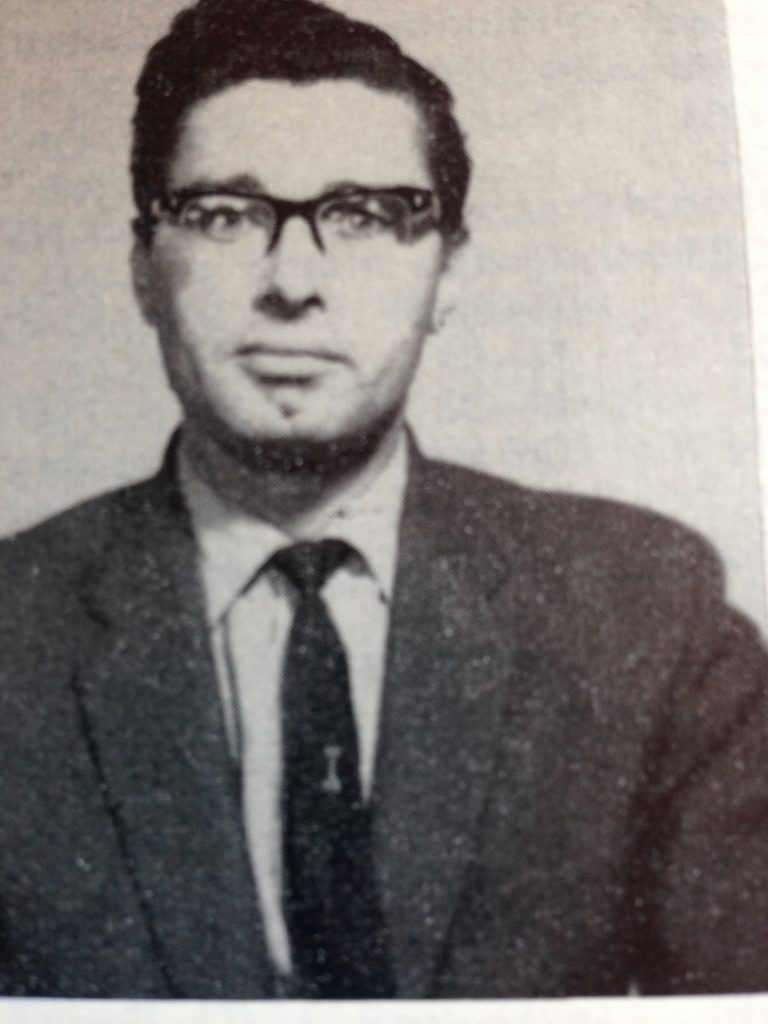

BCN remembers David Hooper who passed away in a Taunton (Somerset) nursing home on Sunday, May 3rd 1998. Probate (#9851310520) was granted in Brighton on June 24th 1998.

Prior to the nursing home David had been living at 33, Mansfield Road, Taunton, TA1 3NJ and before that at 5, Haimes Lane, Shaftesbury, Dorset, SP7 8AJ.

For most of the time between Reigate and Shaftesbury David lived in Whitchurch, Hampshire.

David Vincent Hooper was born on Tuesday, August 31st 1915 in Reigate, Surrey to Vincent Hooper and Edith Marjorie Winter who married in Reigate, Surrey in 1909. On this day the first French ace, Adolphe Pégoud, was killed in combat. He had scored six victories.

David was one of six children: Roger Garth (1910-?), Edwin Morris (1911-1942), Isobel Mary (12/01/1917-2009), Helene Edith (1916-1982) and Elizabeth Anne Oliver (1923-2000) were his siblings.

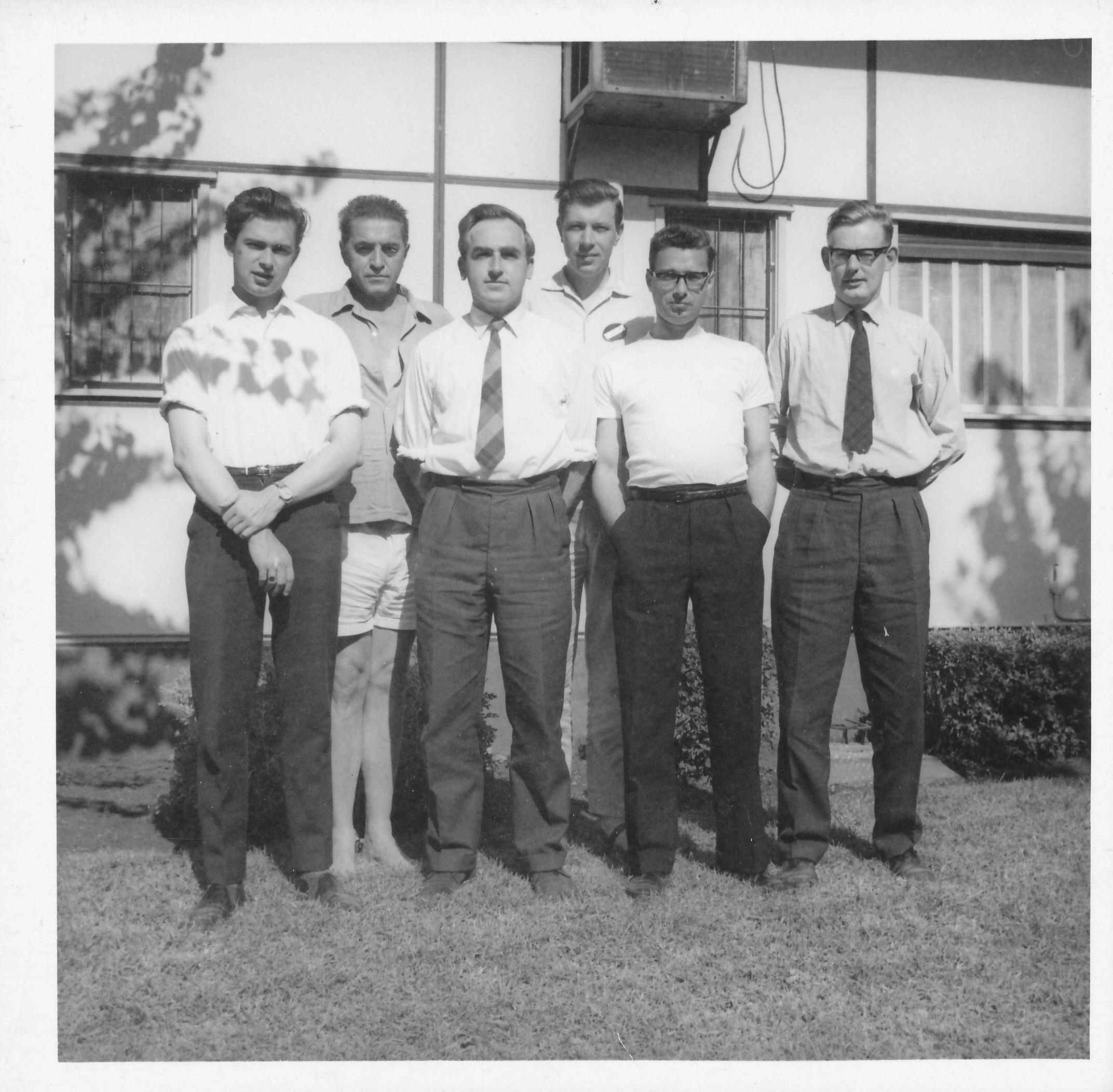

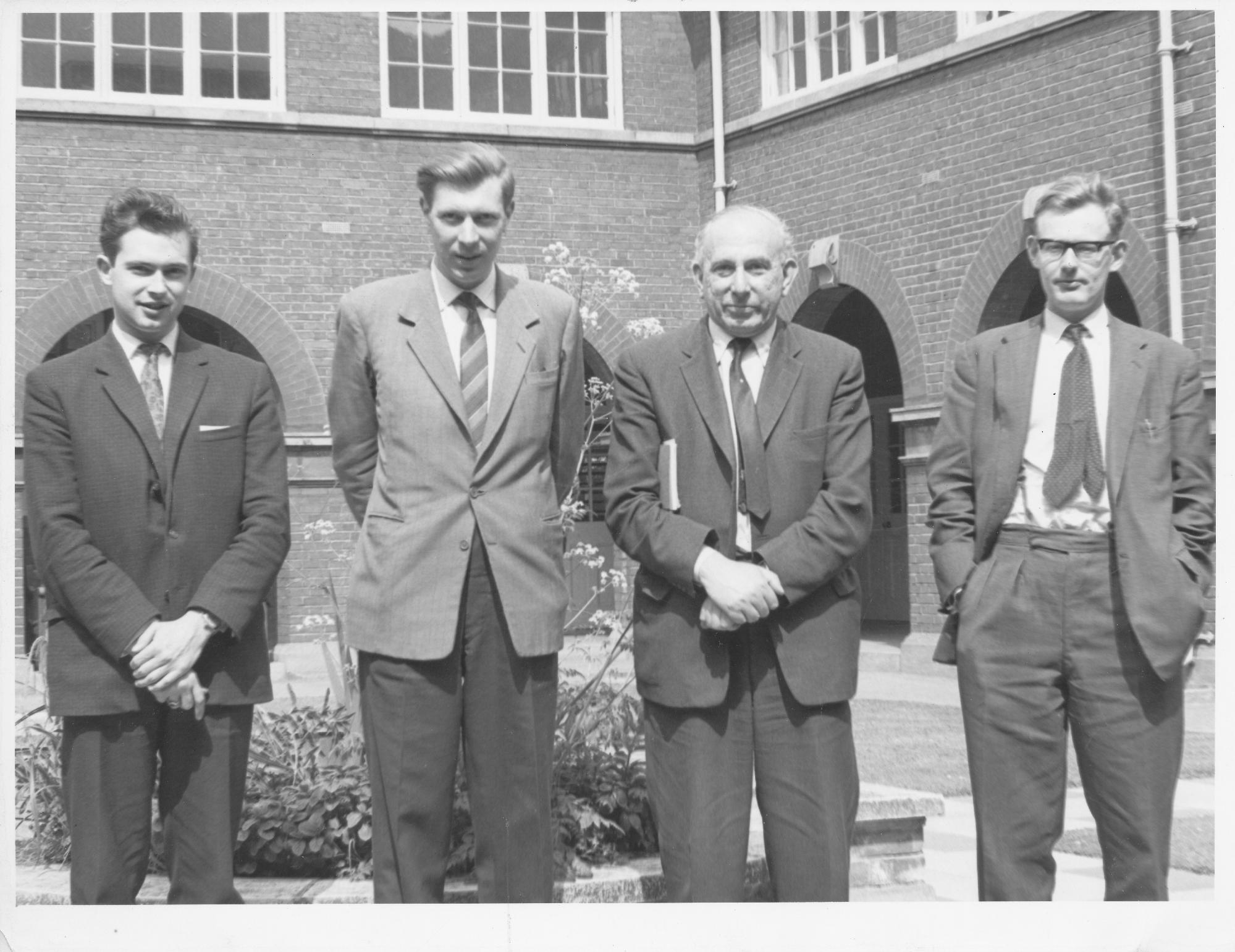

David attended Whitgift School, Croydon, and (thanks to Leonard Barden) we know that “although there was no chess played there in his time he was proud of later accomplishments and often wore an Old Whitgiftians tie, especially for posed photos including this article’s title image and the one in the Chess Notes article by Edward Winter (see the foot of this article).

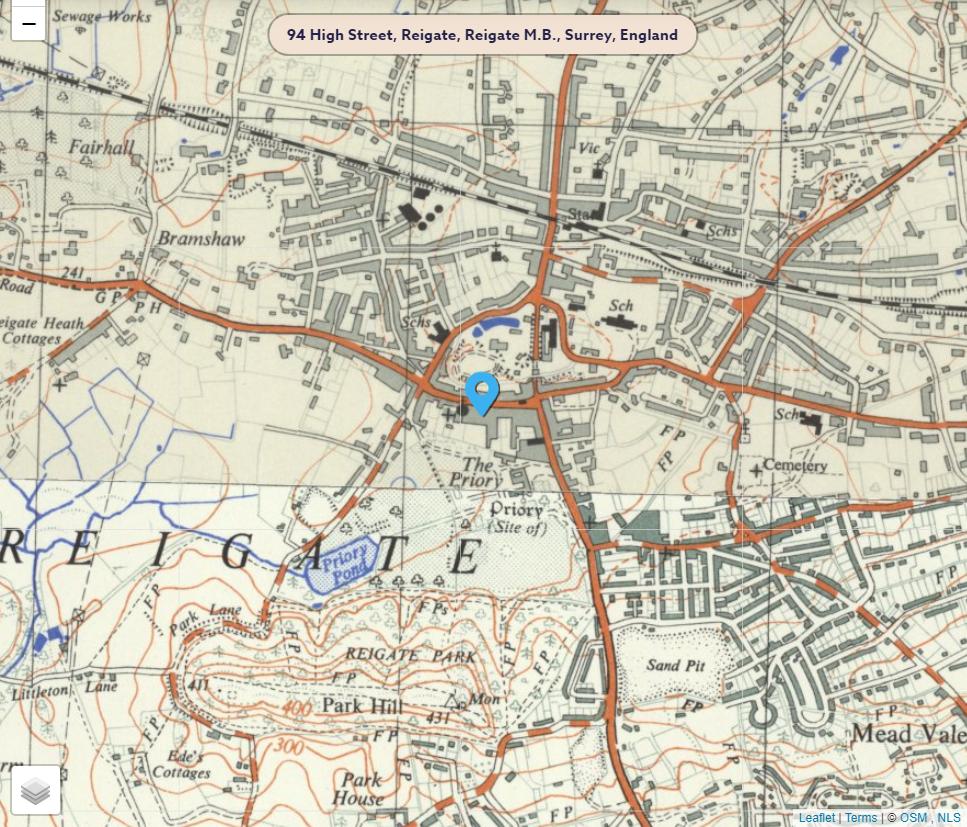

Recorded in the September 1939 register David was aged 24 and living at 94, High Street, Reigate, Surrey:

In 2021 this property appears to be a flat (rather than bridge) over the River Kwai Restaurant:

Living with David was his sister Isobel who was listed a “potential nurse”. David’s occupation at this time was listed as Architectural Assistant and he was single. We think that three others lived at this address at the time but they are not listed under the “100 year rule”. We know that David was also a surveyor and went on to attain professional membership of the Royal Institution of British Architects (RIBA).

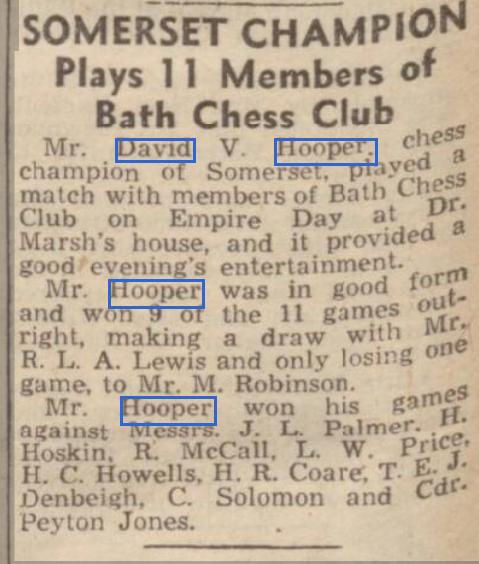

In the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette May 27th 1944 there appeared this report of a simultaneous display on Empire Day (May 24th) at Dr. Marsh’s house:

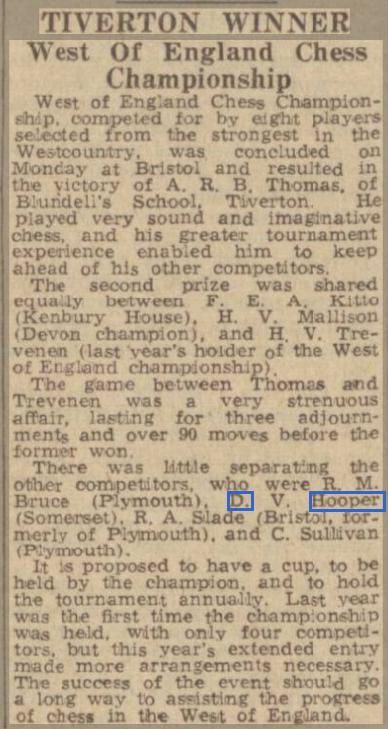

and from The Western Morning News, 9th April 1947 we have:

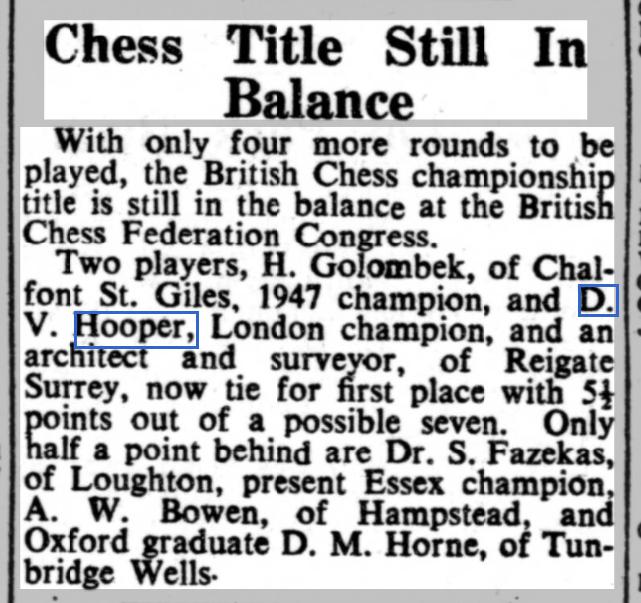

and then from The Nottingham Evening Post, 16th August 1949 we have:

In 1950 aged 35 David married Joan M Higley (or Rose!) in the district of South Eastern Surrey.

Leonard Barden kindly provided us with these memories of David:

“He liked to drive very fast while keeping up a stream of talk with his passenger. I recall his transporting me to the 1950 British Championship in Buxton and feeling in a state of low-key terror the whole journey. When we reached a sign Buxton 30 I felt a great sense of relief that the ordeal was nearly over. Returning two weeks later, some miles down the road we passed Milner-Barry and Alexander in a small car, slowly and carefully driven by M-B whose head nearly reached the roof. As we swept by David gave a celebratory hoot.

I thought this was just me being unduly nervous, but years later Ken Whyld told me he felt the same as a Hooper passenger and that so did most others. David was actually very safe and I don’t think he ever had an accident.

David worked in Middle East for some years and was the chief architect for the construction of a new airport at Aden.

A Guide to Chess Endings was 90% written by David, with chapters then looked over by Euwe and his chess secretary Carel van den Berg. All David’s endgame books are lucidly written and it is a pity where they are not available in algebraic.

When The Unknown Capablanca was published I asked for and received from David an inscribed copy for Nigel Short‘s ninth birthday., which I presented to him personally at an EPSCA team event. Curious to know how it was received, I phoned Nigel’s father (David) a couple of days later and was informed “He’s already on to Capa’s European Tour” (which is I think about 100 pages into the book).” – Thanks Leonard!

Ken Whyld wrote an obituary which appeared in British Chess Magazine, Volume 118 (1998), Number 6, page 326 as follows :

DAVID VINCENT HOOPER died on 3rd May this year in a nursing home in Taunton. He had been in declining health for some months. Born in Reigate, 31st August 1915, his early chess years were with the Battersea CC and Surrey.

He won the (ed. Somerset) County Championship three times, and the London Championship in 1948. His generation was at its chess peak in the years when war curtailed opportunities, but he won the British Correspondence Championship in 1944.

His games from that event are to be found in Chess for Rank and File by Roche and Battersby.

Also at that time, he won the 1944 tournament at Blackpool, defeating veteran Grandmaster Jacques Mieses.

David was most active in the decade that followed, playing five times in the British Championship.

His highest place there was at Nottingham 1954, when, after leading in the early stages, he finished half a point behind the joint champions, Leonard Barden and Alan Phillips.

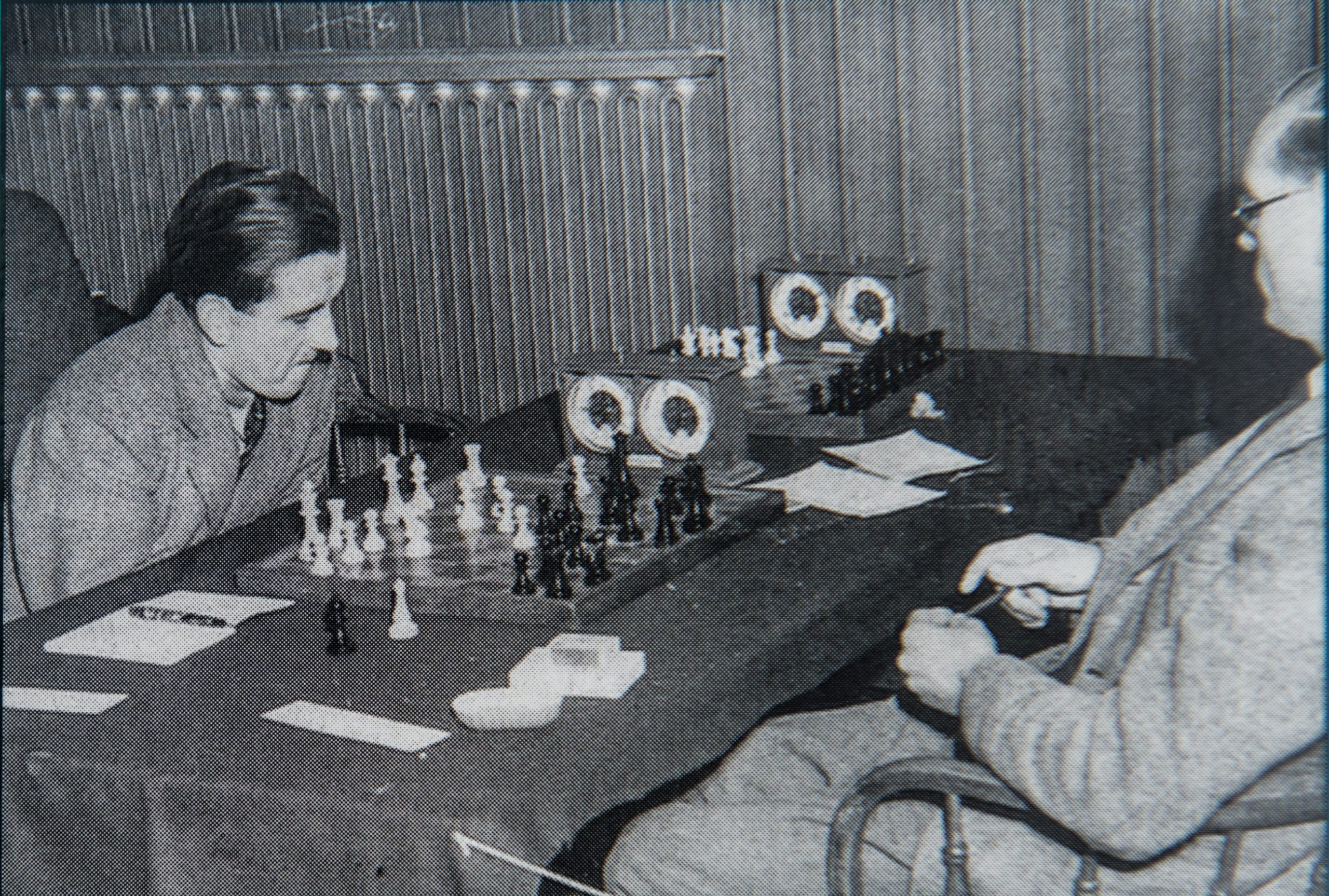

David was in the British Olympic team at Helsinki 1952, and in the same year accidentally played top board for England in one of the then traditional weekend matches against the Netherlands. British Champion Klein took offence at a Sunday Times report of his draw with former World Champion Dr. Euwe on the Saturday and refused to play on Sunday. Thus David was drafted in to meet Euwe, and acquitted himself admirably. Even though he lost, the game took pride of place in that month’s

BCM.

In the following game, played in the Hastings Premier l95l-2, he found an improvement on Botvinnik’s play against Bronstein in game 17 of their 1951 match, when 7.Ng3 was played because it was thought that after 7.Nf4 d5 it was necessary to play 8 Qb3.

In his profession as architect David worked in the Middle East for some years from the mid-1950s, and when he returned to England he made his mark as a writer. His Practical Chess Endgames

has an enduring appeal. Two of his books appeared in the Wildhagen biographical games series on Steinitz, and Capablanca. The last was written jointly with Gilchrist.

With Euwe he wrote A Guide to Chess Endings;

with Cafferty, A Complete Defence to 1.e4;

A Pocket Guide to Chess Endgames;

A Complete Defence to 1.d4;

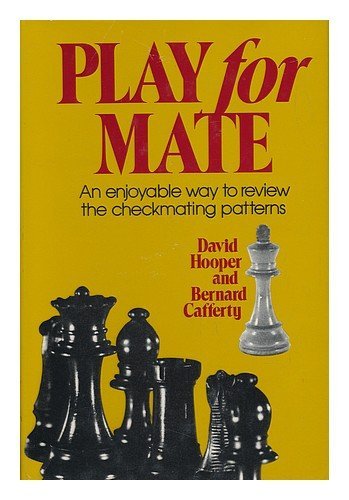

and Play for Mate;

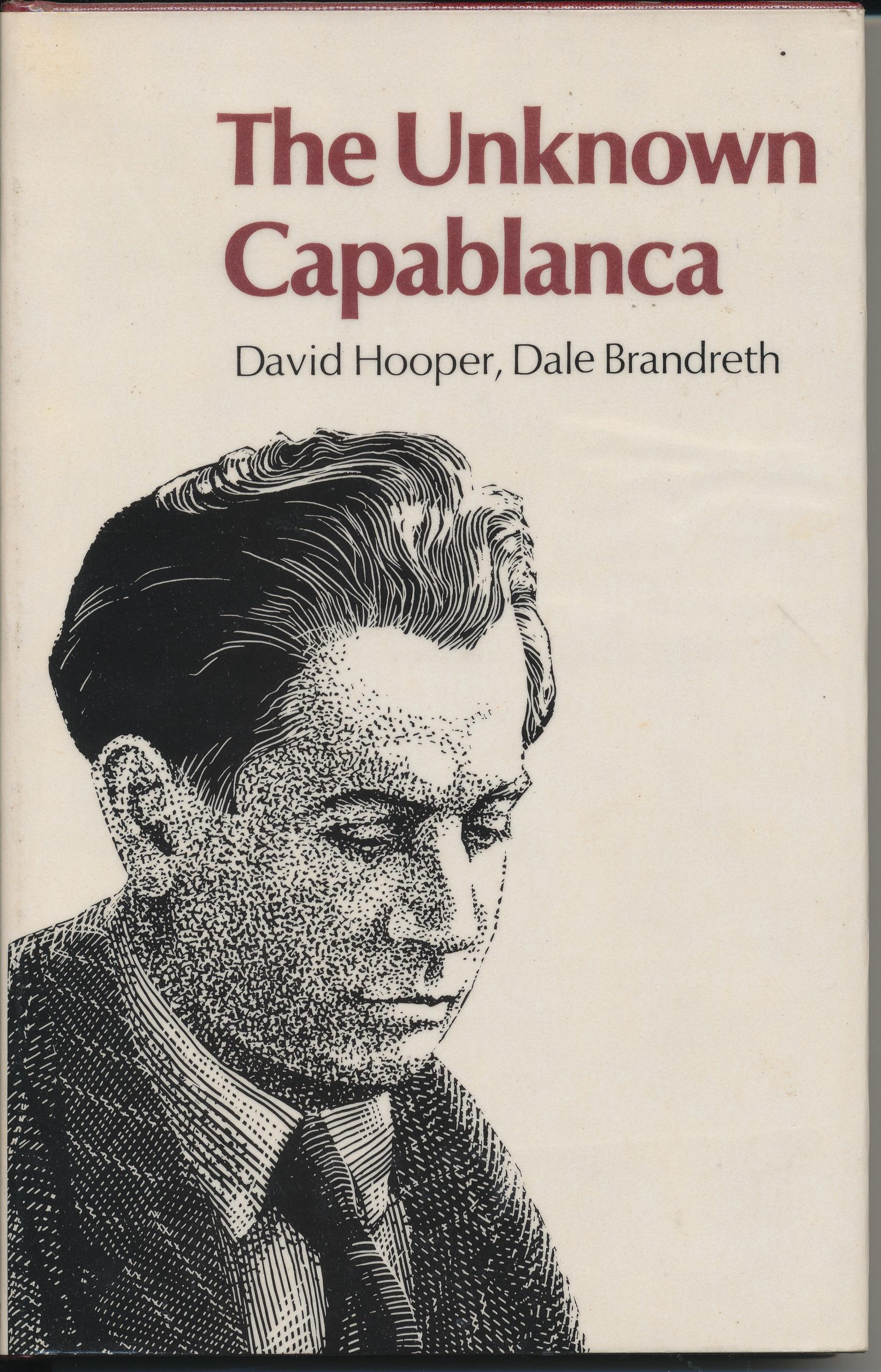

with Brandreth The Unknown Capablanca,

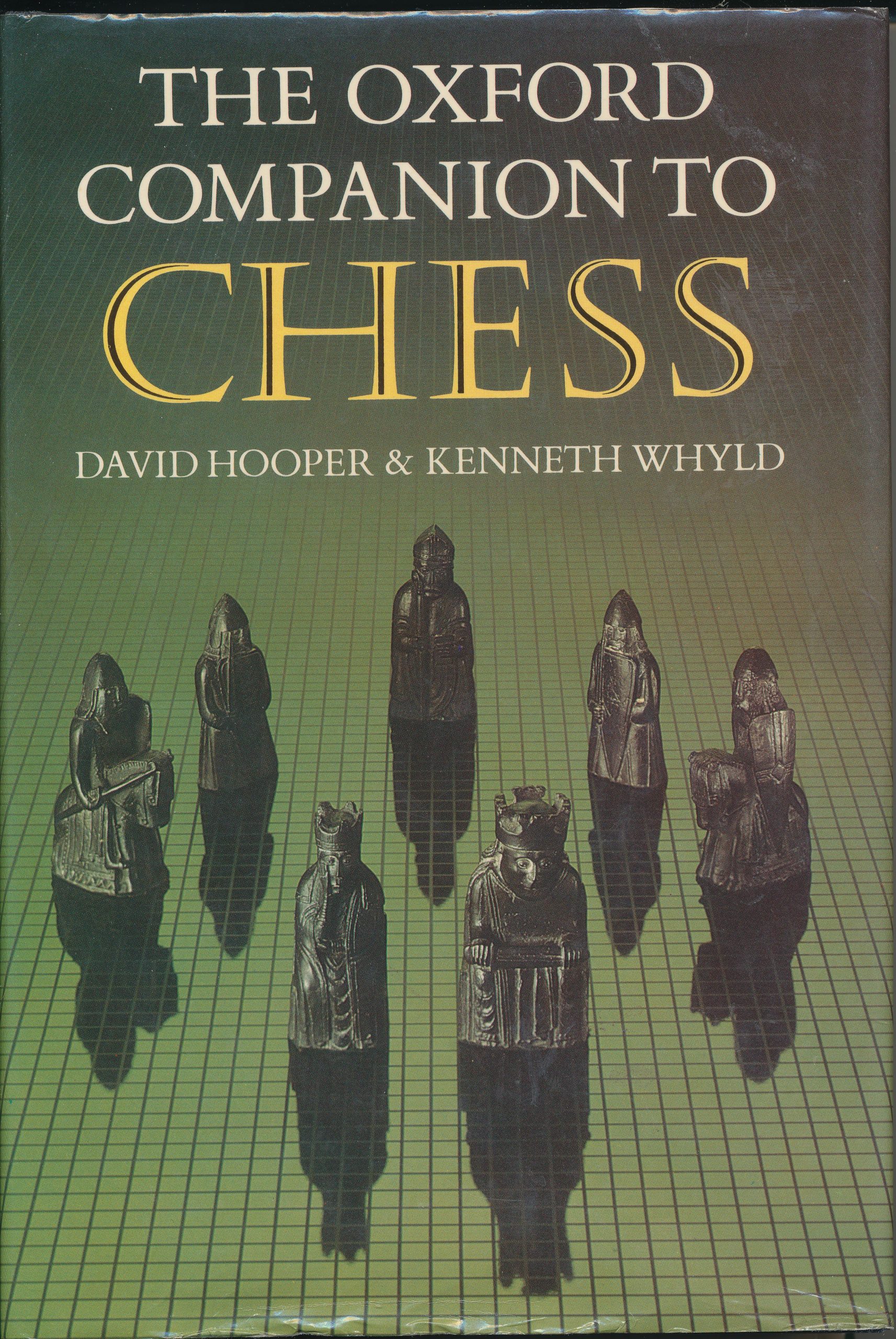

and with Ken Whyld, The Oxford Companion to Chess.

Ken Whyld

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

British amateur (an architect by profession) whose best result was =5 in the British Championship at Felixstowe 1949 along with, amongst others, Broadbent and Fairhurst.

Hooper abandoned playing for writing about chess and has become a specialist in two distinct areas. He is an expert on the endings and has a close knowledge of the history of chess in the nineteenth century.

His principal works : Steinitz (in German), Hamburg, 1968; A Pocket Guide to Chess Endgames, London 1970.

Here is an interesting article from Edward Winter

Here is his brief Wikipedia entry.

BCN remembers Norman Littlewood (31-i-1933 29-iv-1989)

From British Chess Magazine, Volume 109, June (#6), page 265 we have the following obituary which appears to have been lifted and used in the BCF Yearbook from 1989 – 1990, page 14, (editor Brian Concannon) with no acknowledgement :

“We were sorry to (announce the) hear of the death from cancer of Norman Littlewood of Sheffield(31 i 1933 – 29 iv 1989) who played with great force in British Championships of the 1960s.

Born into a working class family of 11 children, Norman played for England in the 1951 Glorney Cup, but did not make his debut in the British Championships until 1963 when he finished second to Penrose. He was then joint runner-up in the next three title contests, impressed at Hastings Premiers, particularly 1963-4 when he was the best of the English players, and represented England in the 1964 and 1966 Olympiads. By 1969, however, he was drifting away from play in the direction of problem and study composition, and his other interests such as bridge. He was also a skilled pianist, a true all-rounder.

A great impression was made on the top players at the 1964 British Championships when Norman won his first four games with his dynamic style. His victims included both Golombek and Clarke. Had he won his next game against Haygarth, as he deserved to do, he would have surely taken the title which fell to his Yorkshire colleague.

Norman was always a modest but assertive character, and with more management might well have challenged Penrose even more closely than he did. Our thanks to elder brother John Littlewood for some of the above information.”

Here is a splendid article from Yorkshire Chess History

See BCF Yearbook 1989-90, page 14.

BCN Remembers Michael John Haygarth (11-x-1934 27-iv-2016)

Here is an article from Yorkshire Chess History

Here is an obituary written by Steve Mann which was published on the ECF web site.

Death Anniversary of Malik Mir Sultan Khan (1905 25-iv-1966)

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld:

Perhaps the greatest natural player of modern times. Born in the Punjab, he learned Indian chess when he was nine, was taken into the household of Sir Umar Hay at Khan, and learned the international game in 1926, Two years later he won the All-India Championship and in the spring of 1929 his patron and master took him to London. Within a few months he won the British Championship, returning to India shortly afterwards. In Europe in May 1930 he began a brief career that included defeats of many leading players.

A striking figure, of dark complexion, with a lean face and broad forehead, his black hair usually turban tied, he sat at the board impassively, showing no emotion in positions good or bad. He did not believe he possessed any special skill, rather that the player applying the greater concentration should win. In events of about category 10 Sultan Khan came second to Tartakower at Liege 1930, third (+5=2-2) after Euwe and Capablanca at Hastings 1930-1, and third ( + 6=3—2) equal with Kashdan after Alekhine and Flohr at London 1932, In events of about category 9 he came fourth or equal fourth at Scarborough 1930, Hastings 1931-2, and Berne 1932 ( + 10=2-3). Sultan Khan won the British Championship again in 1932 and 1933 and played first board for the British Chess Federation in the Olympiads of 1930, 1931, and 1933. In match play he defeated Tartakower (+4=5—3) in 1931 and lost to Flohr ( + 1=3—2) in 1932. At the end of 1933 he went back to India at the bidding of his master. When Sir Umar died Sultan Khan was left a small farmstead near his birthplace, and there he lived out his days. Apparently he had few regrets, A friend visiting him in 1958 found him sitting quietly under the shade of a tree smoking his hookah, chatting with neighbouring farmers while the womenfolk did the work.

In the Indian game of his time the pieces were moved as in international chess but the laws of promotion and stalemate were different, castling was not permitted, and a pawn could not he advanced two squares on its first move. The game opened slowly with emphasis on positional play rather than tactics, and not surprisingly Sultan Khan became a positional player. He had few peers in the middle-game and was among the world’s best two or three endgame players, but he never mastered the openings which, by nature empirical, cannot be learned by the application of common sense alone*

When Sultan Khan first travelled to Europe his English was so rudimentary that he needed an interpreter. He suffered from bouts of malaria and, in the English climate, from continual colds and throat infections, often turning up to play with his neck swathed in bandages. Unable to read or write, he never studied any hooks on the game, and he was mistakenly put in the hands of trainers who were also his rivals in play. Under these adverse circumstances, and having known the international game for a mere seven years, only half of which was spent in Europe, Sultan Khan nevertheless became one of the world’s best ten players. This achievement brought admiration from Capablanca who called him a genius, an accolade he rarely if ever bestowed on anyone else.

R. N. Coles, Mir Sultan Khan (rev, edn, 1977) contains 64 games.

In the March issue of CHESS for 1963, (Volume 28, Number 427, pp.147-155) William Winter wrote this:

The most colourful figure of my time was unquestionably Mir Sultan Khan who appeared in the chess firmament in 1929, blazed like a comet for nearly five years, and then disappeared as suddenly as he had come.

His origins like his end were wrapped in mystery. As far as I could gather he came of generations of Indian peasants who played the native form of chess under a tree in some remote village in the Punjab. Taken under the protection of Sir Umar Hyat Khan he learned the European game, and scored an overwhelming victory in the first Indian championship in which he played. When his patron, Sir Umar, was appointed to an official position in England, he brought Sultan in his train with the object of pitting him against the leading players of the world.

Yates and I were engaged to put him through his paces. I remember vividly my first meeting with the dark skinned man who spoke very little English and answered remarks that he did not understand with a sweet and gentle smile. One of the Alekhine v Bogolyubov matches was in a progress and I showed him a short game, without telling

him the contestants. “l think” he said, “that they both very weak players.” This was not conceit on his part. The vigorous style of the world championship contenders leading to rapid contact and a quick decision in the middle-game, was quite foreign to his conception of the Indian game in which the pawn moves only one square at a time.

Yates and I soon discovered that although he knew nothing of the theory of the openings, his middle-game strategy showed great profundity and his endings were of real master class. In a small double-round tournament for him at the Gambit Café, in which the other players were Yates, Conde, and myself, he did badly, but his Indian record was sufficient to gain him entry to the British Championship held that year at Ramsgate. Few thought that he had a chance of reaching the top half of the table, particularly when he lost in the first round to the Rev. F. E. Hamond. Then however he had an astonishing run of successes and confounded his critics by coming in first. It must be confessed that he was extremely lucky. Drewitt, usually one of the steadiest players, put his queen en prise to a pawn; I allowed him to force a stalemate in an ending in which I was two pawns ahead, and other competitors made similar queer blunders.

A wit suggested that he exercised some oriental hypnotic powers over his rivals, only Hamond, as a parson, being superior to the malign influence. I certainly never remember a championship with so many blunders – probably due to the excessive heat. Sultan created a sensation at Ramsgate in other ways than his chess. He always appeared in flowing white robes and was accompanied by two attendants similarly clad, one to write down his score and the other to supply him with the lemonade which he drank continuously. The latter had to be withdrawn after spilling a glass of the noxious beverage over the trousers of one of the competitors.

The tournament was played in August when Ramsgate was filled with holiday-makers and it may be imagined that Sultan and his retinue were one of the centres of attraction, particularly to the juvenile element. Every day he was accompanied to the congress by a horde of yelling children who, unless the door-keepers were very vigilant, did not stop at the entrance. The noise occasioned by their expulsion from the playing room may have had something to do with the blunders.

Sultan soon showed that this was no flash in the pan for at the Hastings congress (1930-1931) he beat Capablanca, the first game the almost invincible Cuban lost in this country. At the Team Tournament at Hamburg (1930) he also did extremely well on the top board against the best continental opposition though his apparent lack of any intelligible language annoyed some rivals. “What language does your champion speak?” shouted the Austrian, Kmoch, after his third offer of a draw had been met only with

Sultan’s gentle smile. “Chess” I replied, and so it proved, for in a few moves the Austrian champion had to resign. (See a letter to CHESS from Han Kmoch at the end of this article).

From this time onward Sultan went from strength to strength. He won two more British championships and was also highly successful in international events, both in Team Tournaments and individual contests. His greatest achievement was probably his successful match against Tartakover. He soon put off his native dress in favour of more normal apparel but apart from that he remained to the end the inscrutable Oriental. What ideas, if any lay behind that dark impassive face? It was impossible to say, for all the time I knew him he never spoke of any subject but chess. He gradually acquired a knowledge of English and finally spoke quite well. In order to study the chess magazines he also learned to read, but writing was beyond him. I often wrote his letters for him including some to a girl friend whose acquaintance he had made in Hyde Park. The lady seemed to like them.

By 1933, when he won the championship for the last time, he must have been one of the first half dozen or so best players in the world. The highest honours seemed open to him and then ! – just as suddenly as he appeared, he vanished. His patron, Sir Umar, relinquished his post and returned to India taking Sultan with him, and nothing has been since heard of him. He may be dead, but in that case I think the news would have leaked out. I fancy myself that he can still be seen sitting under a tree in some remote village in the Punjab playing the game of his forefathers. If this is so I wonder if he ever dreams of his five years in the West.

and here is a letter from Hans Kmoch following Winter’s memoirs:

Not that it matters, nor that I would cast any blame on the later William Winter whom I knew as a perfect gentleman. It is only for the sake of curiosity that I ask permission to comment on Winter’s story concerning my game against Sultan Khan.

I never asked Winter or anybody else what language Sultan Khan spoke. Nor did I shout (I never do). Sultan Khan and I had met before. What little conversation there was between us was done in English of which we both had a command sufficient for the purpose.

Winter, being not asked, had no opportunity to reply “Chess” or anything else.

I did not offer a draw three times, nor did Sultan Khan, who never smiled, meet my offers with a smile. Nor again did I resign a few moves later. And ! was not the Austrian Champion (contests have not been held at all in my active time).

Sultan Khan had White: we played a Giuoco Piano. After a small number of moves, probably 18 or so, a position was reached which I considered as fully satisfactory for Black.

I offered a draw so as to gain time for my work as a reporter. (I used to be very strict in never offering a draw to anybody unless my position, to the best of my understanding, was fully satisfactory).

Sultan Kahn accepted my offer outright. The game ending in a draw is a provable fact.

New York, 17th April 1963

Hans Kmoch

(we believe Mr. Kmoch! – Editor)

Sultan Khan-Flohr 3rd match game 1932 Caro-Kann

Defence, Exchange Variation

Here is his Wikipedia entry

Here is an excellent article from chess.com

From The Encyclopedia of Chess(Robert Hale, 1970 and 1976) by Anne Sunnucks :

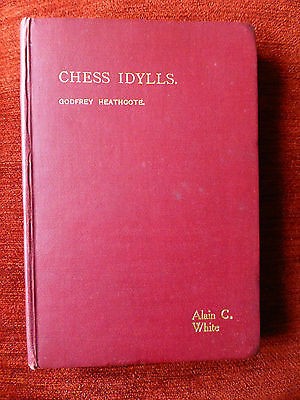

“Problem composer, and deemed to be on of the great masters of the art. Heathcote was born on 20th July 1870 in Manchester, and died on 24th April 1952. whilst in office as the President of the British Chess Problem Society. An advocate of the model mate, Heathcote was one of few composers with the power to combine model mates with strategy. In 1918 a collection of his problems appeared in the A. C. White Christmas series under the title Chess Idylls”

Here is an appreciation from chesscomposers.blogspot.com

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977), Harry Golombek OBE, John Rice writes:

“British problemist, generally regarded as the outstanding English composer of model-mate problems. President of British Chess Problem Society 1951-2.”

BCN Remembers George Walker (13-iii-1803 23-iv-1879)

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks :

“Leading organiser and chess columnist in the last century. Born on 13th March 1803. Founded the Westminster Chess Club in 1831. Published New Treatise on Chess in 1832 and Chess and Chess Players in 1850. Edited the chess column in Bell’s Life of London from 1835 to 1870. Died on 23rd April 1879.

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

“English chess writer and propagandist. Born over his father’s bookshop in London he later became a music publisher in partnership with his father. At a time when he was receiving odds of a rook from Lewis he had the temerity to edit a chess column in the Lancet (1823-4); the first such column to appear in a periodical, it was, perhaps fortunately, short-lived. He tried his hand at composing problems, with unmemorable results; but his play improved. In the early 1830s he was receiving odds of pawn and move from McDonnell, after whose death (1835) Walker was, for a few years, London’s strongest active player.

Walker’s importance, however, lies in the many other contributions he made to the game. He founded chess clubs, notably the Westminster at Huttman’s in 1831 and the St George’s at Hanover

Square in 1843. From 1835 to 1873 he edited a column in Bell’s Life , a popular Sunday paper featuring sport and scandal. Many of his contributions were perfunctory, but on occasion he wrote at length of news, gossip, and personalities in a rollicking style suitable for such a paper. As with many of his writings he was more enthusiastic than accurate. He edited England’s first chess magazine The Philidorian (1837-8). Above all, Walker published many books at a low price: they sold widely and did much to popularize the game. The third edition of his New Treatise (1841) was as useful a manual as could he bought at the time and its section on the Evans gambit was praised by Jaenisch, Walker established the custom of recording games, and his Chess Studies (1844), containing 1,020 games played from 1780 to 1844, has become a classic. For the first time players could study the game as it was played and not as authors, each with his own bias, supposed it should be played. Throughout his life Walker helped chess-players in need. He raised funds for La Bqurdonnais, Capt. W. D. Evans, and other players, and often for their destitute widows.

After his father died (1847) Walker sold their business and became a stockbroker, reducing his chess activities but continuing ‘his many kindnesses. With an outgoing personality he enjoyed the company of those, such as La Bourdonnais, whom he called “jolly good fellows’, an epithet which might well be applied to himself. He was occasionally at odds with Lewis, who was jealous of his own reputation, and Staunton, imperious and touchy; but it seems unlikely that the easy-going Walker, who believed that chess should be enjoyed, intentionally initiated these disputes. He left a small but excellent library of more than 300 books and his own manuscript translations of the works of Cozio, Lolli, and other masters. He should not be confused with William Greenwood Walker who recorded the games of the Bourdon-nais-McDonnell matches 1834, and died soon afterwards “full of years’.

Walker is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, also known as All Souls Cemetery, Harrow Road, Kensal Green, London Borough of Brent, Greater London, W10 4RA England.

The Walker Attack is a variation of the Allagier Gambit :

Here is his Wikipedia entry

Remembering Theophilus Harding Willcocks (19-iv-1912 14-iv-2014)

An innovator in both mathematics and fairy chess.

Here is a short article from chesscomposers.com

A short mention by Michael McDowell

Willcocks, Theophilus Harding

Die Schwalbe, 1967

Prize

What was Black’s previous move?

Here is an excellent article on squaring.net

An article from matplus.net

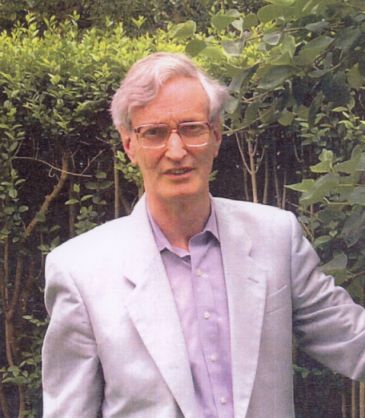

BCN remembers Timothy George Whitworth (31-vii-1932 17-iv-2019)

Here is an excellent article from Brian Stephenson

and here is an appreciation by John Beasley

Here is an obituary from The Guardian