Here is his Wikipedia entry

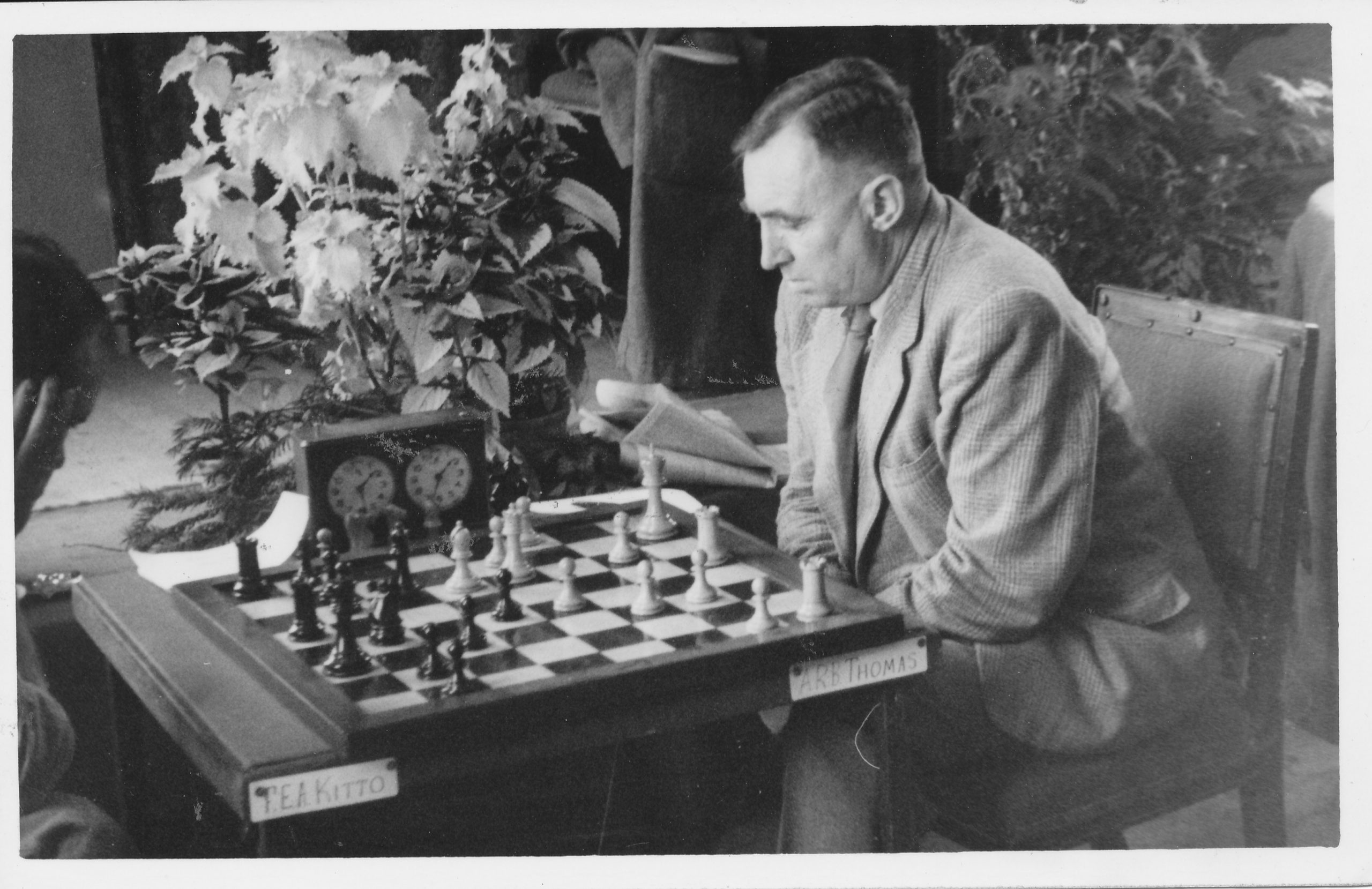

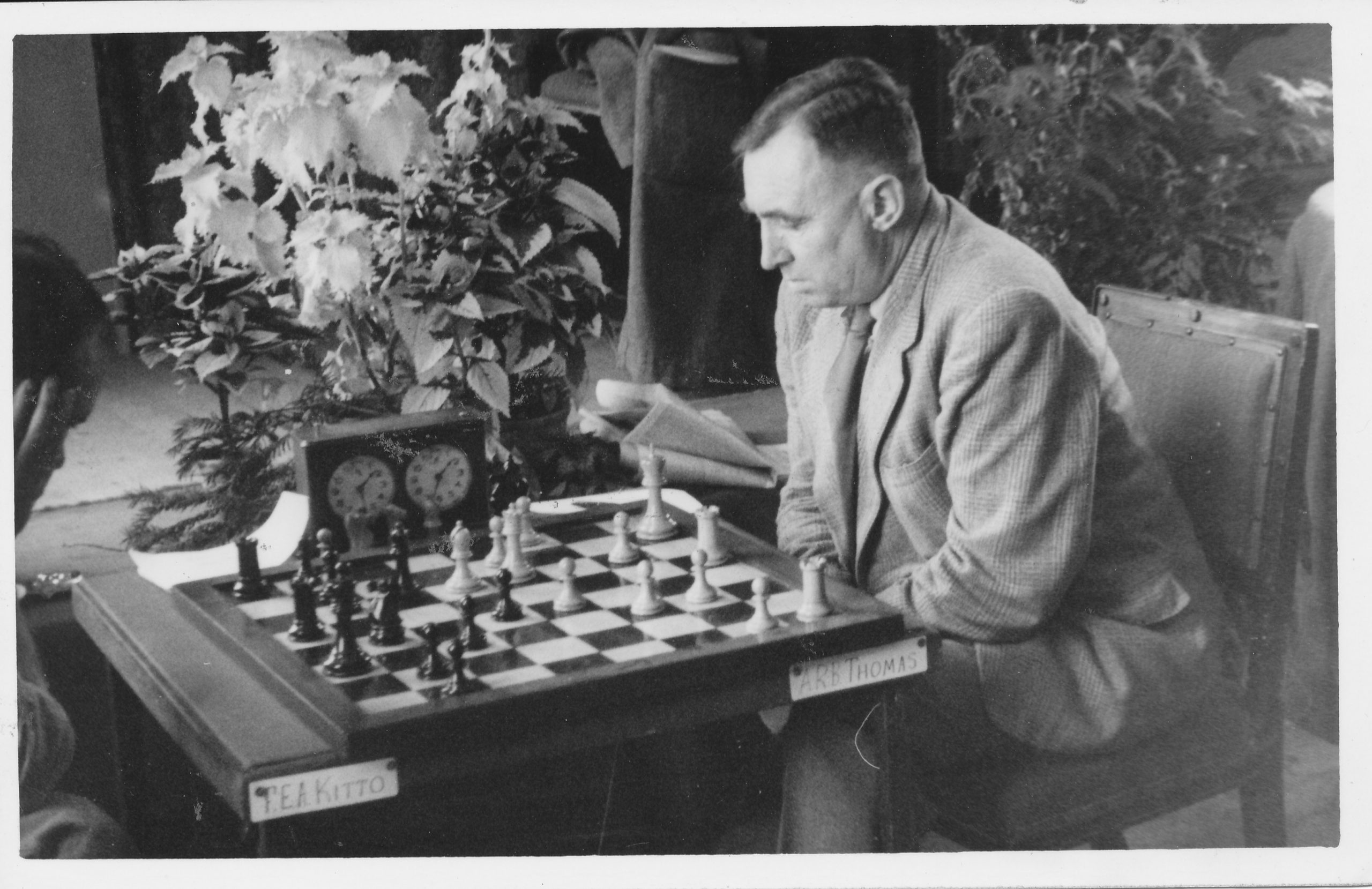

BCN remembers Andrew Rowland Benedick Thomas (11-x-1904 16-v-1985)

We cannot improve on this excellent article about ARBT on the Chess Devon web site

Here is his Wikipedia entry

BCN remembers Andrew Rowland Benedick Thomas (11-x-1904 16-v-1985)

We cannot improve on this excellent article about ARBT on the Chess Devon web site

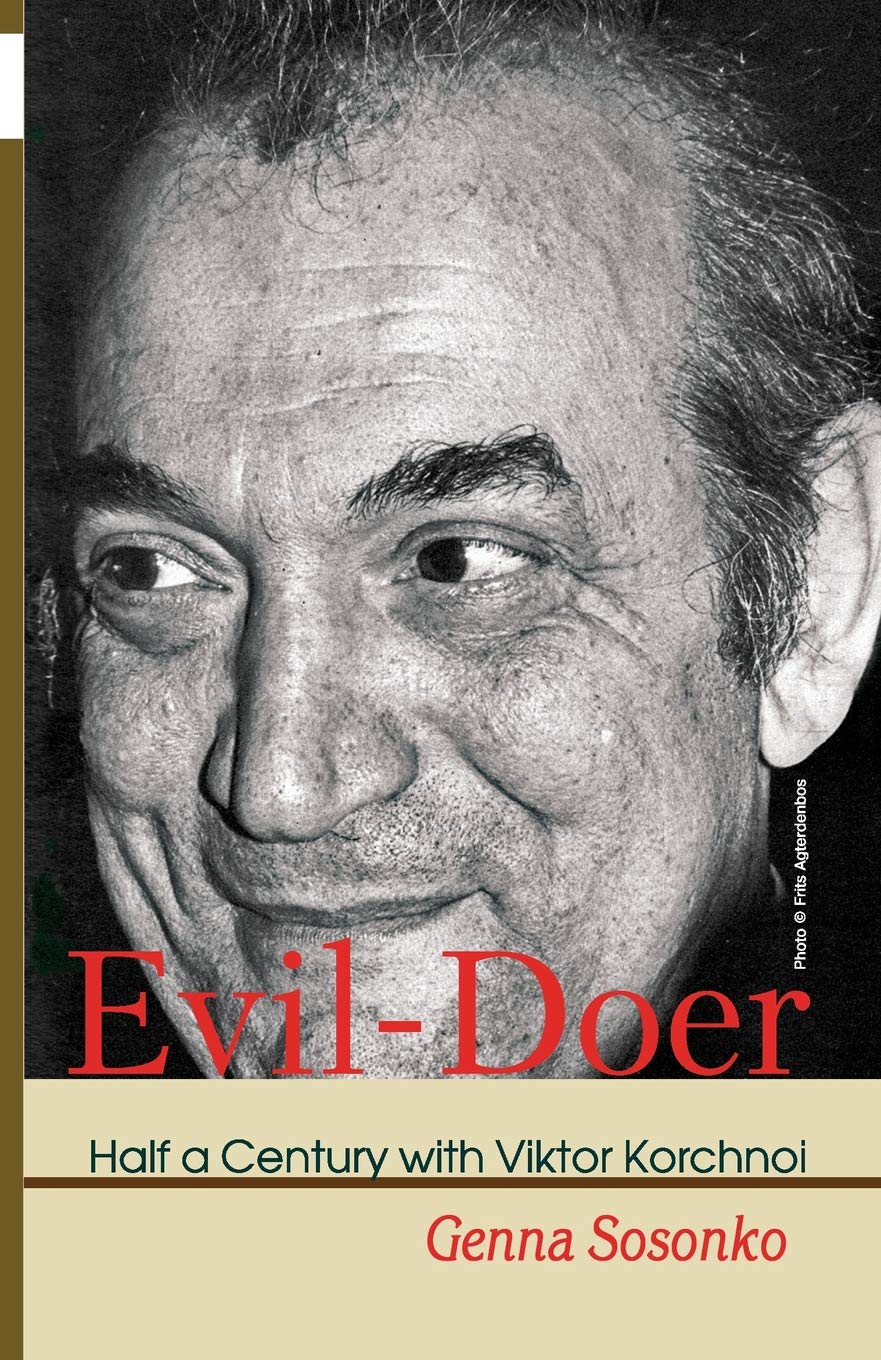

Evil-Doer : Half a Century with Viktor Korchnoi : Genna Sosonko

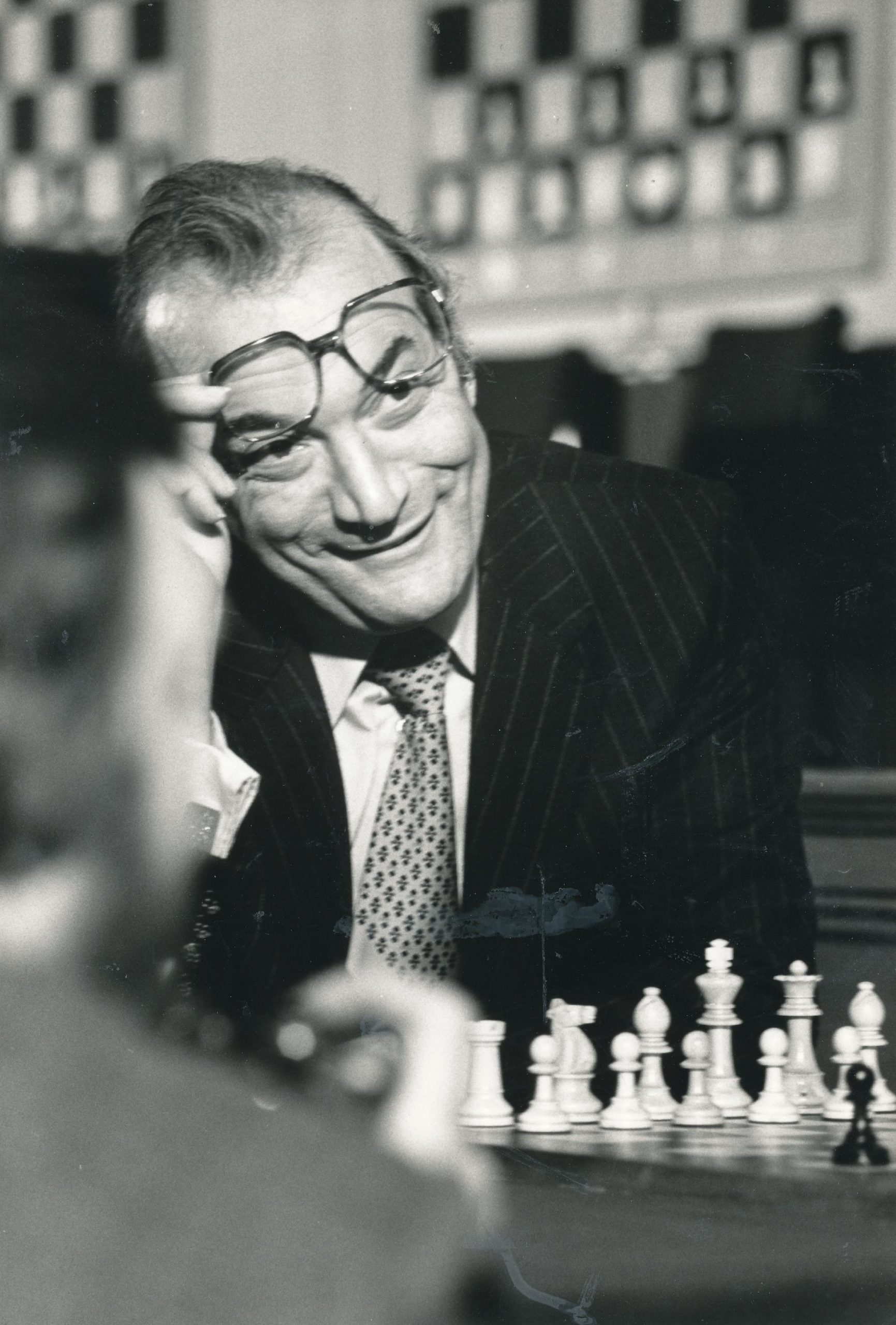

Genna Sosonko emigrated from the USSR to the Netherlands in 1972. For the past 20 years or so he’s made a career out of writing essays and books about chess in the Soviet Union, and interviewing many of the leading players from that period.

It was Saturday 17 January 1976. The height of the English Chess Explosion. Richmond Junior Chess Club had opened its doors for the first time just a few months earlier.

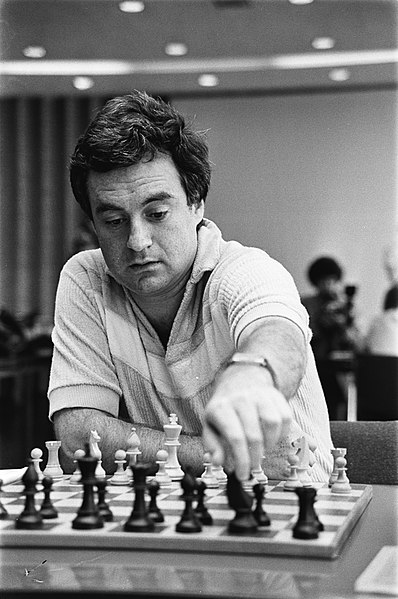

As was customary at the time, the visiting Soviet GMs who had been competing at Hastings played simuls against prizewinners from the London Junior Championships, which in those days attracted most of the country’s top young players. And so it was that I was there at a London school to witness two of the all-time greats, Bronstein and Korchnoi, taking on the cream of England’s up and coming chess talents.

The contrast was noticeable. Bronstein played fast, took some risks and finished quickly (+17 =9 -4). Korchnoi played slowly, taking every game seriously, and using 7 hours to complete his 30 games (+20 =9 -1), losing only to a certain N Short. He said at the time something to the effect that he wanted his young opponents to understand what it was like to play against a strong grandmaster.

This story sums up the difference between two men who had much in common but a very different attitude towards chess.

Bronstein was born in Ukraine, the son of a Jewish family. Korchnoi’s Polish Catholic father and Jewish mother had moved from Ukraine to Leningrad a few years before he was born. Both men were obsessed with chess while neither had great social and communication skills. Both, of course, came within a whisker of becoming world champion.

I’ve recently reviewed Sosonko’s memoirs of Smyslov and Bronstein: the book in front of me now is without doubt the most successful of the trilogy. Korchnoi and Sosonko had been close friends for half a century, although at one point not on speaking terms for some time.

Korchnoi could at times be rude, argumentative and bad-tempered, but that was part of the man, and his friends, such as Sosonko, accepted and perhaps even respected him for it. On reading an article in which Nigel Short, his young conqueror all those years ago in the London Juniors simul, described him as a ‘cantankerous old git’, he confessed that, although his English was pretty good, he was only familiar with one of the three words. Growing up as he did during the Siege of Leningrad, suffering his parents’ divorce and the death of his father, poverty, hunger and ill-health, you might think, along with Sosonko, that his difficult personality was understandable. You might also ask yourself whether it was, at least in part, something he was born with.

“I have problems communicating with other people”, he once said. “Therefore, I do what I like the most. Most of all I like chess, and, to be honest, I don’t know what else I could do.” (No, I don’t know when or where he said it, but that’s Sosonko for you. No sources, just lots of ‘he saids’, allegations and speculations.)

Korchnoi admitted and accepted his differences, while Bronstein, to use the current vogue word, masked his differences.

Bronstein peaked early, while Korchnoi peaked remarkably late. Bronstein seemed to play for fun, driven by fantasy and imagination, while Korchnoi was a dour and dogged defender who took every game seriously. But it was Bronstein who gradually fell out of love with chess, his obsession turning from the game itself to the perceived injustices he suffered. Korchnoi, in contrast, like Edith Piaf, regretted nothing and remained passionately devoted to chess right to the end of his life.

A long and eventful life it was, too. From wartime hardships to chess stardom, political asylum in the West, world championship matches against Karpov, and his final decades spent quietly (as if Korchnoi could ever be quiet) in Switzerland, it’s all here. Readers of Sosonko’s other books will know what to expect. There’s no chess in it at all, so, unless you’re inspired by Korchnoi’s determination, it won’t do anything to improve your rating. Nor is it an academic history: just memoir and anecdotes. I’m not convinced by the title: ‘evil-doer’ was how he was referred to by some Soviet players after his defection. It’s a title I might use about Hitler or Stalin, but Korchnoi, whatever his faults, didn’t do evil. But if you want 300+ pages about the man, written by a friend and admirer for half a century, you’ll enjoy reading this book.

Richard James, Twickenham 15th May 2020

Book Details :

Official web site of Elk and Ruby

BCN Remembers Charles Dealtry Locock (27-ix-1862 13-v-1946)

From chessgames.com :

“Charles Dealtry Locock was born in Brighton, England. He won the British Amateur Championship in 1887 (after a play-off) and passed away in London.”

From Wikipedia :

“Charles Dealtry Locock (1862 – 1946) was a British literary scholar, editor and translator, who wrote on a wide array of subjects, including chess, billiards and croquet.[1]”

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

The Locock Gambit is in the Philidor Defence, named after the English player Charles Dealtry Locock (1862 – 1946). The gambit is probably sound; Black should play 4…Be7 instead of 4…h6

Here are some studies from aarves.org

James Pratt informs BCN that CDL was an early trainer of Elaine Saunders. See here for more.

From The Chess Bouquet, (1897), page 212 : (taken from chessgames.com)

“Perhaps many players who are inclined to pooh, pooh the efficacy of problem training will be surprised to find that such an expert player, as Mr. Locock has proved himself to be, is equally at home in the sister art. Yet such is the case, and although his fame rests chiefly upon his many brilliant victories in cross-board encounters, the strategetic qualities of his compositions, and the ease and facility with which he penetrates the inmost recesses of problem, have secured him place in the foremost ranks of British problemists. Born in 1862, and educated at Winchester College and University College, Oxford, Mr. Locock early displayed fondness for chess, and for five years he played for Oxford v. Cambridge.

In 1887 he won the amateur championship tournament of the British Chess Association without losing game. In the Masters’ International Tournament, held at Bradford in 1888, he scored seven antl half games against very powerful array of talent. The Masters’ International Tournament, held at Manchester, in 1890, found him somewhat below par, but in 1801 he won the British Chess Club Handicap without losing game. In 1892 he tied with Bird for fourth prize in the National Masters’ Tournament. Emanuel Lasker (then rapidly forcing his way to the throne, so long and honourably held by Wilhelm Steinitz) won the first prize, with score of nine James Mason second, seven and half; Rudolph Loman third, seven and Messrs. Bird and Locock six and half each. Seven others competing.

During the past four years Mr. Locock has played some twenty-six match games without losing one. In team matches he has only lost one since 1886. These include the two telephone matches, British Chess Club v. Liverpool and also the cable match, British Chess Club v. Manhattan Club, 1895, when Mr. Locock, at board three, drew with Mr. A. B. Hodges; and the cable match, British Isles v. United States, March, 1896, when Mr. Locock again drew his game with Mr. E. mes on board five.

Partially owing to want of practice, Mr. Locock is gradually retiring from serious chess, although we trust many years will elapse ere he finally says good-bye to the scene of his triumphs. Life is generali) voted too short for chess, yet, in addition to the sterling work already alluded to, Mr. Locock has found time to edit the well-known excellent chess column in Knowledge, and enrich the already huge store ot problems with many stategetical positions. His “Miraculous Adjudicator” and Three Pawns ending, published in the B.C.M., having been greatly admired by connoisseurs.

Mr. Locock has favoured us with few humorous remarks on what he terms the vice of problemmaking,” and with these we conclude our sketch of perhaps the strongest living amateur player-problemist “

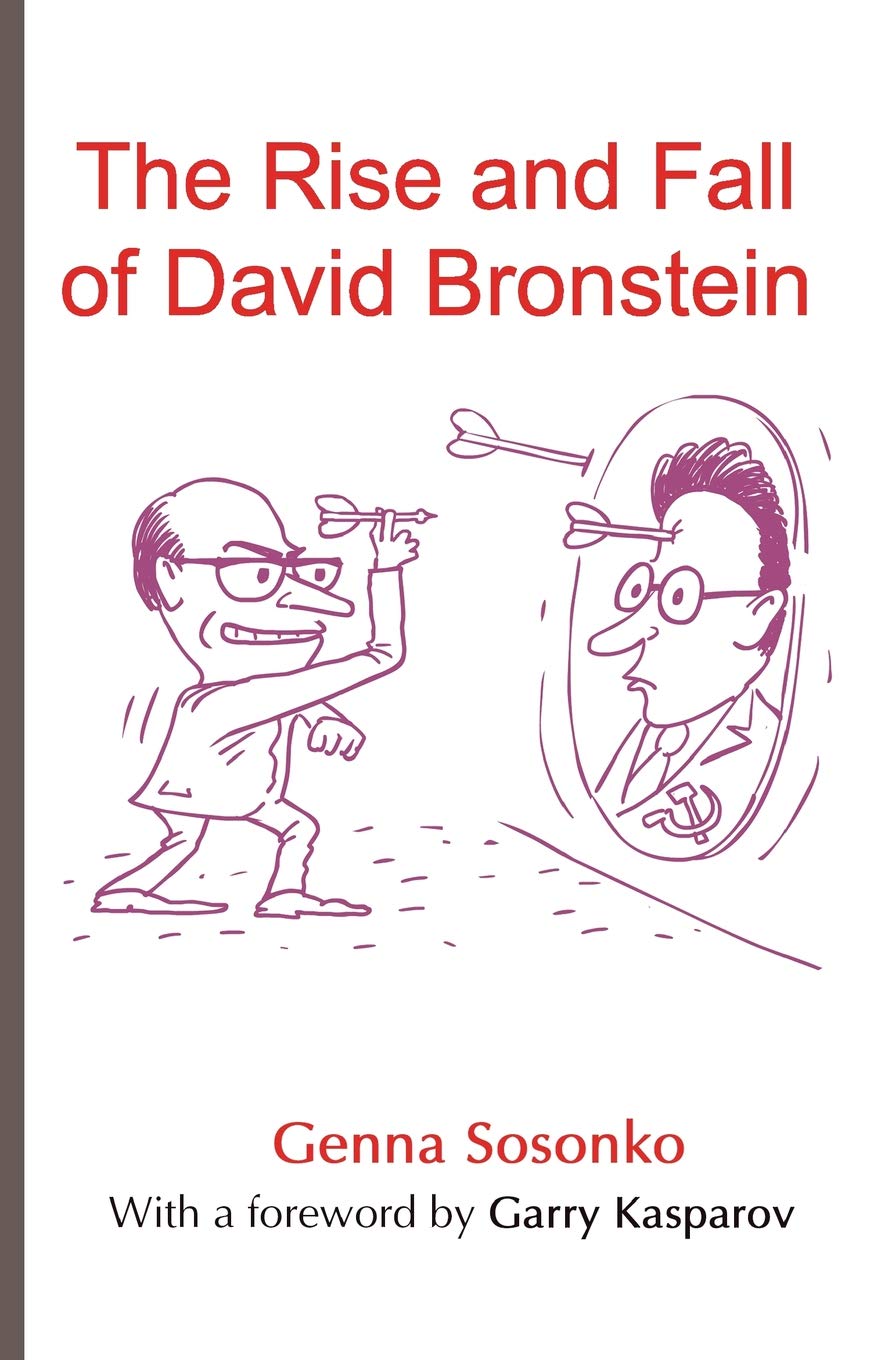

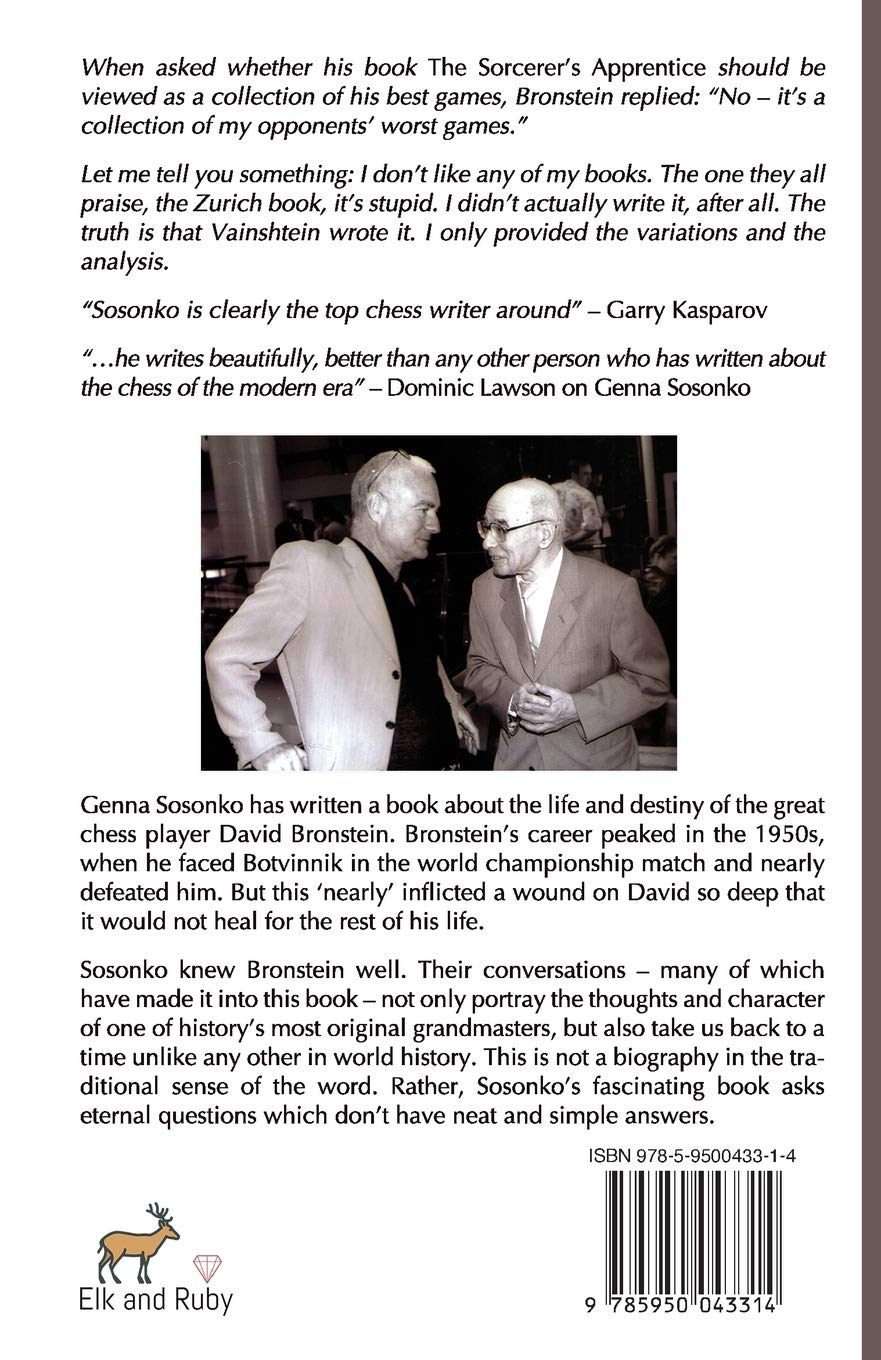

The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein : Genna Sosonko

Genna Sosonko emigrated from the USSR to the Netherlands in 1972. For the past 20 years or so he’s made a career out of writing essays and books about chess in the Soviet Union, and interviewing many of the leading players from that period.

This is the position at the adjournment (remember them?) of the 23rd game of the 1951 World Championship match between Mikhail Botvinnik (White in this game) and David Bronstein, the subject of this memoir by Genna Sosonko. A position that would haunt Bronstein for the rest of his life. He was a point up with just two games to play but if the match was drawn Botvinnik would retain his title. Bronstein had been at least equal at various times during the game, but, in this complex ending, had erred a couple of moves earlier, and, if Botvinnik had sealed Bb1 (Bc2 also does the trick) he’d have had a winning advantage.

But when the envelope was opened the next day, 42. Bd6 appeared. The game continued 42… Nc6 43. Bb1, when Na7, planning b5, would have drawn, leaving Bronstein only requiring a draw with White in the 24th game to become the 7th World Champion. Instead, though, he played Kf6, and Botvinnik eventually won, although Stockfish suggests that Black might still have drawn.

I’d always assumed that Bronstein, as befits his play, was a witty and charming man, but Sosonko paints a very different picture. An annoying eccentric who would never stop talking about his obsessions, notably Botvinnik and the above game, but who frequently contradicted himself as to whether or not he really wanted to become World Champion, and as to how much pressure he was put under by the Soviet authorities, both in that match and later. A man with a never ending stream of ideas about chess, some brilliant, but others crazy. (Perhaps this is not an uncommon trait amongst chess players – I can think of several friends who are very similar.) A man who, as he aged, became sad and embittered, regretting and resenting his chess career and wishing he’d done something else with his life.

At times I thought Sosonko was turning into Bronstein himself, as he regaled me with more and more anecdotes from other players telling similar stories about Bronstein’s oddities, and more and more conversations with him in his final years, all saying very much the same thing. “Shut up, Genna! You’ve made your point. Can’t we look at some chess instead?”

No, it seems we can’t. You won’t find any chess at all in this book. Even when a game is discussed, as in the above example, we don’t get to see the moves. Yes, most readers can do what I did and look them up, but having to do that is both frustrating and unnecessary.

An air of sadness pervades much of the book. While I agree that it’s important to know something of the personalities behind the moves, Bronstein, like, for example, Alekhine and Fischer, is best remembered by his games.

And yet – there’s a lot of interest here. A lot of material, admittedly anecdotal, about chess in the Soviet Union, and, in particular, about Bronstein’s éminence grise Boris Vainshtein. Sosonko calls him the Prince of Darkness, and I was very much reminded of Dominic Cummings, himself a chess player in his youth, who plays a similar role in the life of another Boris. Descriptions of Bronstein’s chess philosophy often made me stop and think anew about the nature and purpose of chess, and about my own chess philosophy.

With a firmer editorial hand this could have been an excellent book. Cut back on the repetitive anecdotes and the descriptions of his final years. Add the positions and moves when a game is being discussed. Perhaps expand the section on Bronstein’s chess philosophy. Nevertheless, for anyone interested in post war chess Sosonko’s book is still an essential read.

I’ll close, if I may, with a couple of personal thoughts. Even though he studied geography, not psychology, Sosonko likes to psychoanalyze his subjects, tending towards theories based on nurture rather than nature. These days most of us take a different view. A child presenting with his oddities today would probably receive various diagnoses and labels. For better or for worse? You tell me.

Finally, here’s Sosonko explaining why Bronstein, at the end of his life, was popular with children.

“People rejected by the adult world are often children’s best friends. They are not quite normal to other adults, but are full of charm for children: fully-grown charming eccentrics who never become proper adults.” Guilty as charged.

Richard James, Twickenham 10th May 2020

Book Details :

Official web site of Elk and Ruby

BCN remembers Dr. IM István (Stefan) Fazekas who passed away in Buckhurst Hill, Essex on Wednesday, May 3rd, 1967 and the death was recorded in the district of Redbridge.

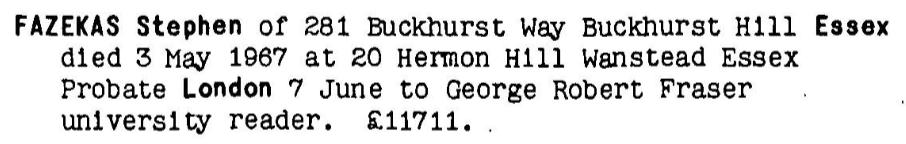

The probate record of June 7th, 1967 is thus:

István Fazekas was born in Satoraljaujhely, Hungary on Wednesday, March 23rd 1898. He adopted the name Stefan subsequently. Satoraljaujhely is very much on the Hungary – Czechoslovakian border and records for Fazekas variously show both countries as his country of birth.

The September 1939 register records Stephen Fazekas as being married, a refugee, and a general practitioner living with his wife Helen (born 17th July 1900) at 21, Old Gloucester Street, Bloomsbury, Camden, London WC1. The “household” had a total of fourteen residents and this building in 2021 appears to be part of the Mary Ward Centre and presumably was providing temporary accommodation.

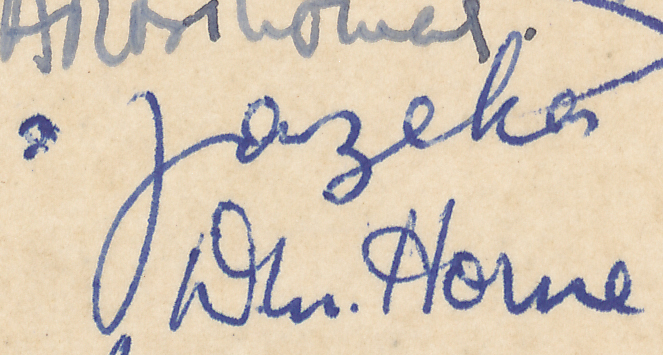

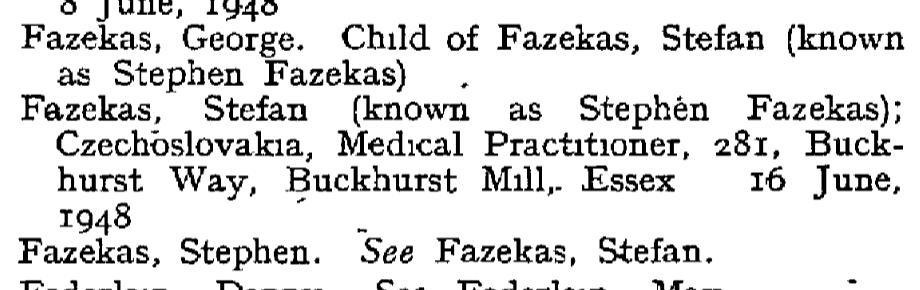

The 1948 London Gazette records that on June 16th he lived at 281 Buckhurst Way, Buckhurst Hill, Essex and that he and Helen had a son, George. On this day Stefan was granted UK naturalisation following the swearing of an oath of allegiance:

The above notice is further validated by the official record stored at The National Archive, Kew, reference HO 334/234/4061.

From British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXXVII, Number 7 (July), pages 195-6 we have an obituary written by Peter Clarke :

The death of Dr. Fazekas on May 3rd has deprived British chess of one of its leading and most colourful figures. Ever since he came to this country nearly thirty years ago he took an active part, in the game at all levels, from club to international, rarely missing the chance – even when not in the best of health- to test his strength in competition and express his ideas afresh.

Stefan Fazekas was born on March 23rd, 1898, at Sitoraljaujhely on the Hungarian-Czechoslovak border, but it was not until a few years after the Great War, in which he served and was wounded, that he got the opportunity to play serious tournament chess. By present-day standards, however, events were few and far between, and the game always had to take second place to his medical work.

The Doctor’s best international performances, for which he was later awarded the master title by F.I.D.E., came in the ‘thirties. In 1931, for instance, he was 2nd at Kosice, 3rd at Brno and 3rd at Prague. As it remained throughout his career, his play was excessively variable: fine conceptions were always liable to be ruined by blunders or impetuosity. The following game, played at Munchentratz in 1933, shows all going well; it earned inclusion in Le Lionnais’ anthology Les Prix de beauté aux échecs.

In 1939 Dr. Fazekas brought his family to England and established himself as a successful and much loved G.P. at Buckhurst Hill, Essex. He soon took a dominating part in county chess and went on to win the championship eleven times. In national events his inconsistency seemed too great a handicap, but at Plymouth in 1957, after so many tries, he astounded everyone by winning the British Championship in front of, among others, Alexander and Penrose.

(Ed. He was the oldest person to win the British Championship at 59 years of age.)

The next year fate struck him a cruel blow when he was left out of the B.C.F. team for the Munich Olympiad. Yet after returning the trophy in protest he overcame his bitterness and took his place once more in the championship tournament-he could not resist the thrill of the struggle.

(Ed. The Selection Committee was: RJ Broadbent (Chairman), CHO’D Alexander, RWB Clarke, WA Fairhurst, Dr. S. Fazekas, H. Golombek, JH van Meurs, and AF Stammwitz (Secretary).)

Knowing that his best over-the-board days were behind him, the Doctor decided to go in for correspondence chess in 1959, and he at once found himself surprisingly at home in it. Here his old weaknesses could be set aside and his vast experience put to good use. Moreover, his great love for chess enabled him to devote hours of work to the analysis of a single move if necessary.

His rapid successes in this field won him a place in the Semi-Finals of the 5th World Correspondence Championship (where he finished 4th out of 14) and led to his being chosen as Board 1 for the British team in the 5th Olympiad. On the results of these events he was awarded the title of international C.C. master. That he deserved it may be judged from this fine strategic win against a grandmaster (C.C.) opponent in the individual tournament.

At the time of his death Dr. Fazekas had made a score of 5 out of 7 in the Olympiad Final and was still engaged with Zagorovsky of the U.S.S.R., a performance which showed his correspondence play to be close to grandmaster standard. And to end one’s days actually playing a World Champion is a distinction which I am sure would have appealed to this Doctor’s rich sense of humour.

While Dr. Fazekas’ social work as a humanist was for the peace of the world, in chess he was noted as a great fighter, in some ways reminiscent of Lasker. There was no retirement for him.

At Ilford in 1965 and 1966 he eagerly took on and held his own with a generation fifty years his junior, and this year he had once again qualified to play in the British Championship. The tournament at Oxford will not seem quite the same without him. I and his many friends will miss his wit and ebullience, his generosity, his love of life and chess.-P. H. C.

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977), Harry Golombek OBE:

“International Master and British Champion 1957. A dangerous attacking player but weak in positional play. Fazekas was born at Satoraljaujhely on the Hungarian-Czechoslovakian border. In the earlier part of his career he was Czechoslovak. This period comprised his international career and he was awarded the title of international master many years later after he had emigrated to England in 1939.

It was his results in 1931 that gained him the title: 2nd at Kosice, 3rd at Prague and 3rd at Brno ahead of Honlinger, Mikenas, Noteboom and Rellstab.

In England he became much-respected general medical practitioner, and was therefore really an amateur at chess since he devoted himself to his profession. But he played much club and county chess and was eleven times champion of his county, Essex.

In 1957, almost out of the blue, he won the British Championship in a strong year that included Penrose and Alexander.

He played a number of times in the championship after that, but never looked like gaining the title since increasing years took their toll. He was in fact the oldest player ever to have won the British Championship.

In 1959 he took up correspondence chess and became an international correspondence chess master.”

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Robert Hale, 1970 & 1976), Anne Sunnucks:

“International Master (1953), International Correspondence Chess Master and British Chess Champion in 1957.

Fazekas was born in Satoraljaujhely on the Hungarian-Czechoslovakian border, on 23rd March 1898. He was awarded the title of International Master for his performances in the 1930s, which included 2nd at Kosice 1931; 3rd at Brno 1931 and 3rd at Prague 1931.

In 1939 he emigrated to England, where he practised as a general medical practitioner at Buckhurst Hill in Essex. Chess always took second place to his profession, and his tournament appearences were limited. He played regularly in county and club events and was 11 times champion of Essex.

In 1957, to everyone’s surprise, he won the British Championship, ahead of such players as Penrose, Alexander, Clarke, Wade and Milner-Barry. Shortly after this victory came a bitter blow to Fazekas when he was not selected as a member of the British Chess Federation team for the 1958 chess Olympiad at Munich.

Fazekas returned the championship trophy in protest at his exclusion and the controversy over whether he should or should not have been selected raged for many months.

Dr. Fazekas’s love of chess eventually overcame his resentment and he continued to appear regularly in the British Championship, but never again repeated his success.

In 1959, he took up correspondence chess and reached the semi-finals of the fifth World Correspondence Chess Championship and was selected to play on top board for the British team in the Fifth Correspondence Chess Olympiad. This event was still in progress at the time of this death. He died on 3rd May 1967, at his home in Buckhurst Hill.”

Dr. Fazekas was Southern Counties (SCCU) Champion twice in 1951-2 and 1952-53.

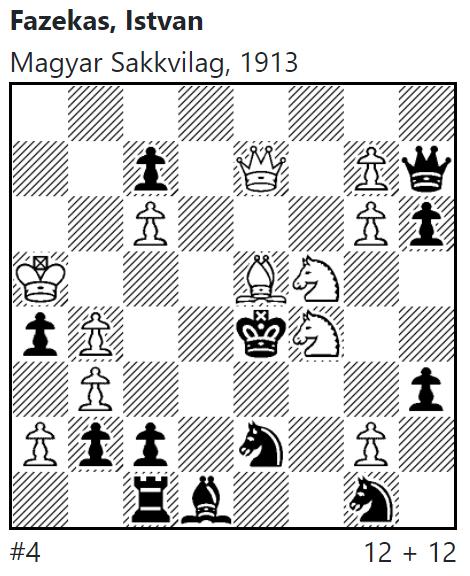

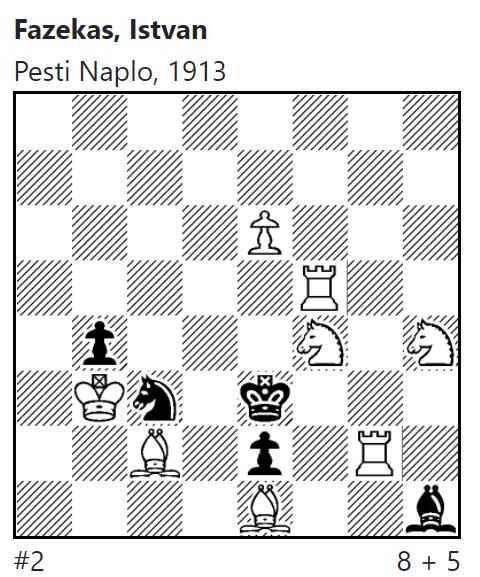

In his early days he was a successful composer of problems:

From Chessgames.com :

“Dr Stefan (ne Istvan) Fazekas was born in Satoraljaujhely, Hungary. Awarded the IM title in 1953 and the IMC title in 1964, he was British Champion in 1957 and is the oldest player ever to have won the title. He passed away in 1967 in Buckhurst Hill, Essex, England.”

In Edward Winter’s Chess Notes there is a note from Leonard Barden concerning SFs spoken English (under Chess Note #10361)

Here is his brief Wikipedia entry

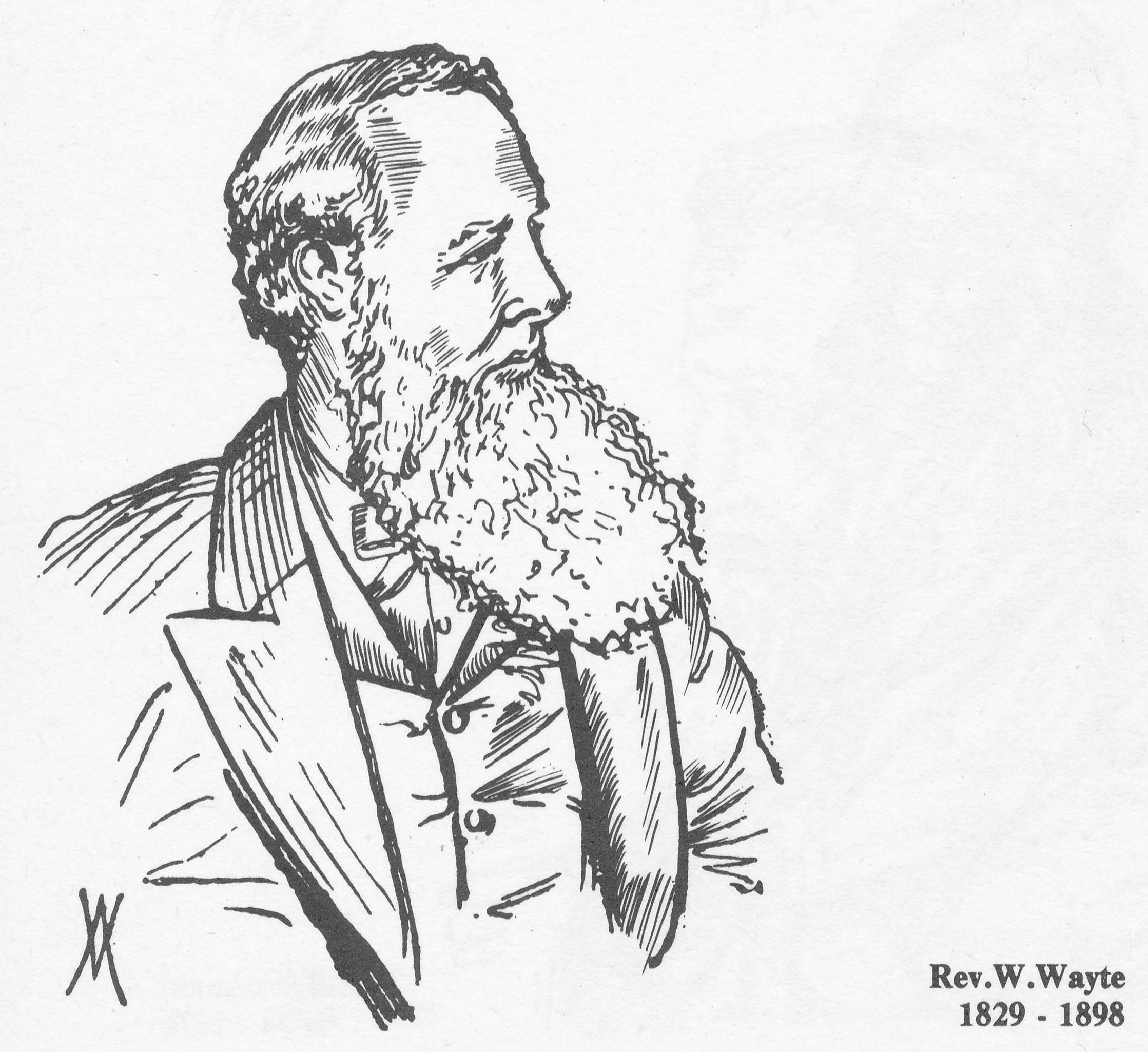

Remembering Reverend William Wayte (04-ix-1829 03-v-1898)

Here is his Wikipedia entry

See article by JS Hilbert in the June 2012 BCM, page 296

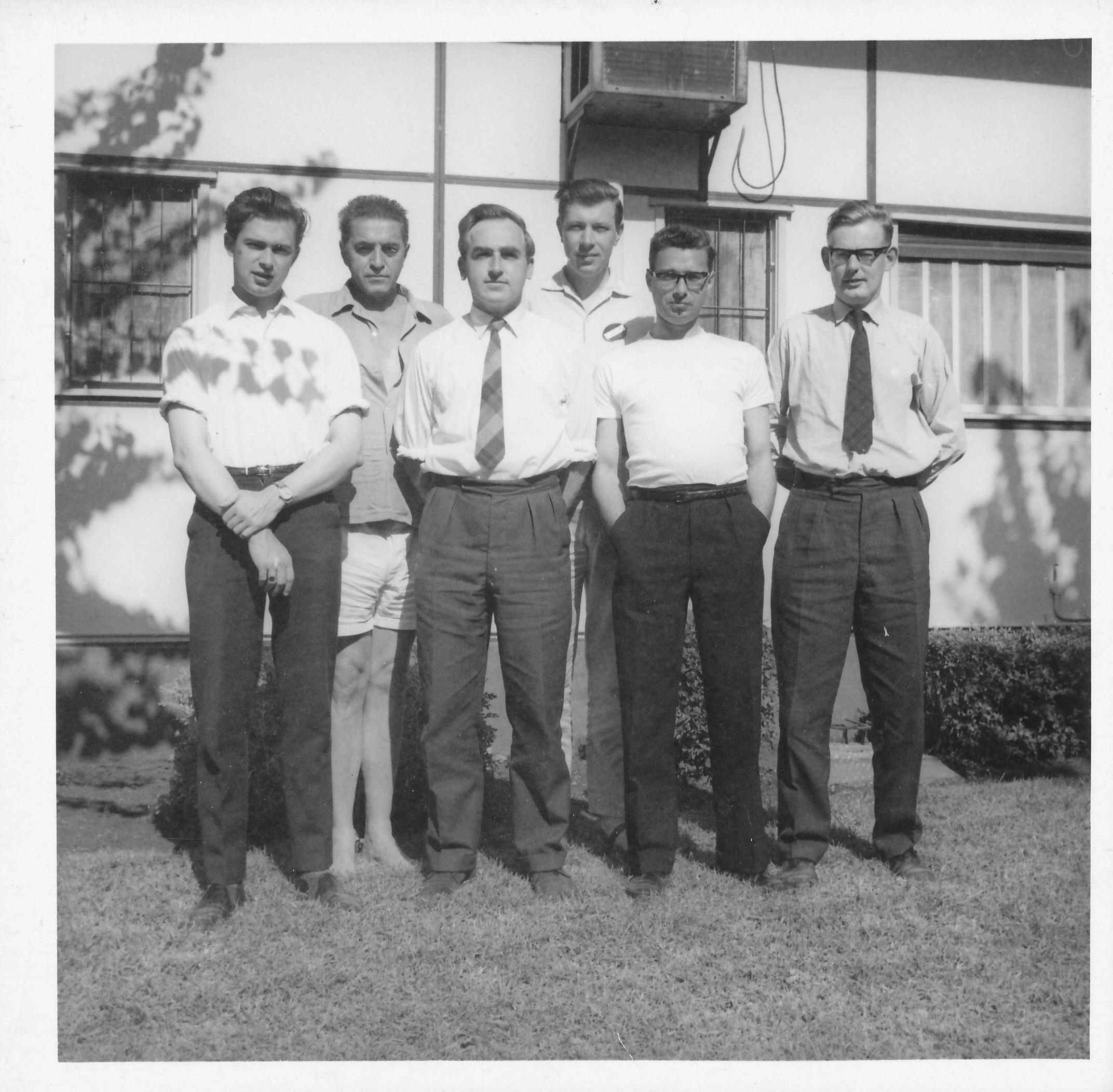

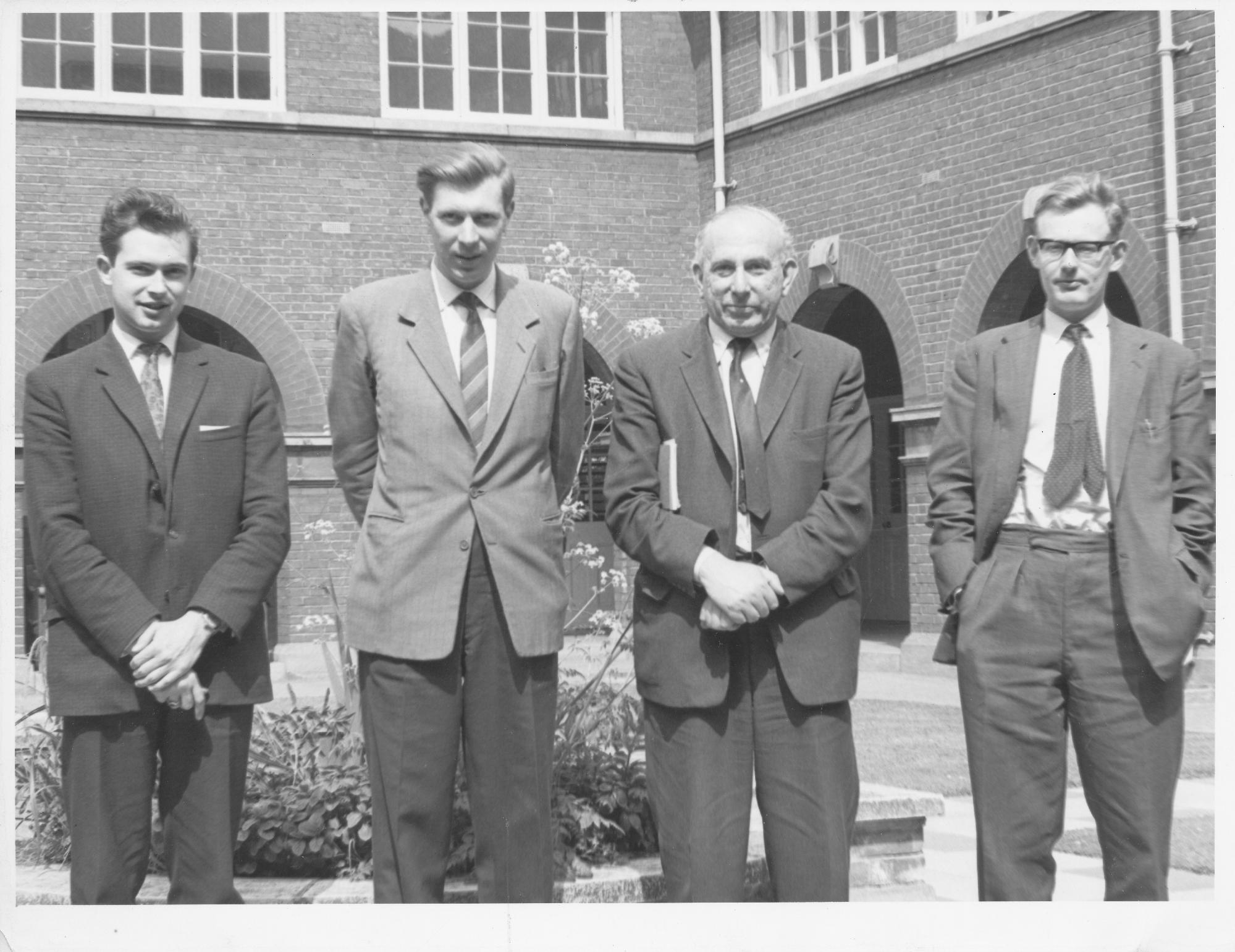

BCN remembers Norman Littlewood (31-i-1933 29-iv-1989)

From British Chess Magazine, Volume 109, June (#6), page 265 we have the following obituary which appears to have been lifted and used in the BCF Yearbook from 1989 – 1990, page 14, (editor Brian Concannon) with no acknowledgement :

“We were sorry to (announce the) hear of the death from cancer of Norman Littlewood of Sheffield(31 i 1933 – 29 iv 1989) who played with great force in British Championships of the 1960s.

Born into a working class family of 11 children, Norman played for England in the 1951 Glorney Cup, but did not make his debut in the British Championships until 1963 when he finished second to Penrose. He was then joint runner-up in the next three title contests, impressed at Hastings Premiers, particularly 1963-4 when he was the best of the English players, and represented England in the 1964 and 1966 Olympiads. By 1969, however, he was drifting away from play in the direction of problem and study composition, and his other interests such as bridge. He was also a skilled pianist, a true all-rounder.

A great impression was made on the top players at the 1964 British Championships when Norman won his first four games with his dynamic style. His victims included both Golombek and Clarke. Had he won his next game against Haygarth, as he deserved to do, he would have surely taken the title which fell to his Yorkshire colleague.

Norman was always a modest but assertive character, and with more management might well have challenged Penrose even more closely than he did. Our thanks to elder brother John Littlewood for some of the above information.”

Here is a splendid article from Yorkshire Chess History

See BCF Yearbook 1989-90, page 14.

BCN Remembers Michael John Haygarth (11-x-1934 27-iv-2016)

Here is an article from Yorkshire Chess History

Here is an obituary written by Steve Mann which was published on the ECF web site.

Death Anniversary of Malik Mir Sultan Khan (1905 25-iv-1966)

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld:

Perhaps the greatest natural player of modern times. Born in the Punjab, he learned Indian chess when he was nine, was taken into the household of Sir Umar Hay at Khan, and learned the international game in 1926, Two years later he won the All-India Championship and in the spring of 1929 his patron and master took him to London. Within a few months he won the British Championship, returning to India shortly afterwards. In Europe in May 1930 he began a brief career that included defeats of many leading players.

A striking figure, of dark complexion, with a lean face and broad forehead, his black hair usually turban tied, he sat at the board impassively, showing no emotion in positions good or bad. He did not believe he possessed any special skill, rather that the player applying the greater concentration should win. In events of about category 10 Sultan Khan came second to Tartakower at Liege 1930, third (+5=2-2) after Euwe and Capablanca at Hastings 1930-1, and third ( + 6=3—2) equal with Kashdan after Alekhine and Flohr at London 1932, In events of about category 9 he came fourth or equal fourth at Scarborough 1930, Hastings 1931-2, and Berne 1932 ( + 10=2-3). Sultan Khan won the British Championship again in 1932 and 1933 and played first board for the British Chess Federation in the Olympiads of 1930, 1931, and 1933. In match play he defeated Tartakower (+4=5—3) in 1931 and lost to Flohr ( + 1=3—2) in 1932. At the end of 1933 he went back to India at the bidding of his master. When Sir Umar died Sultan Khan was left a small farmstead near his birthplace, and there he lived out his days. Apparently he had few regrets, A friend visiting him in 1958 found him sitting quietly under the shade of a tree smoking his hookah, chatting with neighbouring farmers while the womenfolk did the work.

In the Indian game of his time the pieces were moved as in international chess but the laws of promotion and stalemate were different, castling was not permitted, and a pawn could not he advanced two squares on its first move. The game opened slowly with emphasis on positional play rather than tactics, and not surprisingly Sultan Khan became a positional player. He had few peers in the middle-game and was among the world’s best two or three endgame players, but he never mastered the openings which, by nature empirical, cannot be learned by the application of common sense alone*

When Sultan Khan first travelled to Europe his English was so rudimentary that he needed an interpreter. He suffered from bouts of malaria and, in the English climate, from continual colds and throat infections, often turning up to play with his neck swathed in bandages. Unable to read or write, he never studied any hooks on the game, and he was mistakenly put in the hands of trainers who were also his rivals in play. Under these adverse circumstances, and having known the international game for a mere seven years, only half of which was spent in Europe, Sultan Khan nevertheless became one of the world’s best ten players. This achievement brought admiration from Capablanca who called him a genius, an accolade he rarely if ever bestowed on anyone else.

R. N. Coles, Mir Sultan Khan (rev, edn, 1977) contains 64 games.

In the March issue of CHESS for 1963, (Volume 28, Number 427, pp.147-155) William Winter wrote this:

The most colourful figure of my time was unquestionably Mir Sultan Khan who appeared in the chess firmament in 1929, blazed like a comet for nearly five years, and then disappeared as suddenly as he had come.

His origins like his end were wrapped in mystery. As far as I could gather he came of generations of Indian peasants who played the native form of chess under a tree in some remote village in the Punjab. Taken under the protection of Sir Umar Hyat Khan he learned the European game, and scored an overwhelming victory in the first Indian championship in which he played. When his patron, Sir Umar, was appointed to an official position in England, he brought Sultan in his train with the object of pitting him against the leading players of the world.

Yates and I were engaged to put him through his paces. I remember vividly my first meeting with the dark skinned man who spoke very little English and answered remarks that he did not understand with a sweet and gentle smile. One of the Alekhine v Bogolyubov matches was in a progress and I showed him a short game, without telling

him the contestants. “l think” he said, “that they both very weak players.” This was not conceit on his part. The vigorous style of the world championship contenders leading to rapid contact and a quick decision in the middle-game, was quite foreign to his conception of the Indian game in which the pawn moves only one square at a time.

Yates and I soon discovered that although he knew nothing of the theory of the openings, his middle-game strategy showed great profundity and his endings were of real master class. In a small double-round tournament for him at the Gambit Café, in which the other players were Yates, Conde, and myself, he did badly, but his Indian record was sufficient to gain him entry to the British Championship held that year at Ramsgate. Few thought that he had a chance of reaching the top half of the table, particularly when he lost in the first round to the Rev. F. E. Hamond. Then however he had an astonishing run of successes and confounded his critics by coming in first. It must be confessed that he was extremely lucky. Drewitt, usually one of the steadiest players, put his queen en prise to a pawn; I allowed him to force a stalemate in an ending in which I was two pawns ahead, and other competitors made similar queer blunders.

A wit suggested that he exercised some oriental hypnotic powers over his rivals, only Hamond, as a parson, being superior to the malign influence. I certainly never remember a championship with so many blunders – probably due to the excessive heat. Sultan created a sensation at Ramsgate in other ways than his chess. He always appeared in flowing white robes and was accompanied by two attendants similarly clad, one to write down his score and the other to supply him with the lemonade which he drank continuously. The latter had to be withdrawn after spilling a glass of the noxious beverage over the trousers of one of the competitors.

The tournament was played in August when Ramsgate was filled with holiday-makers and it may be imagined that Sultan and his retinue were one of the centres of attraction, particularly to the juvenile element. Every day he was accompanied to the congress by a horde of yelling children who, unless the door-keepers were very vigilant, did not stop at the entrance. The noise occasioned by their expulsion from the playing room may have had something to do with the blunders.

Sultan soon showed that this was no flash in the pan for at the Hastings congress (1930-1931) he beat Capablanca, the first game the almost invincible Cuban lost in this country. At the Team Tournament at Hamburg (1930) he also did extremely well on the top board against the best continental opposition though his apparent lack of any intelligible language annoyed some rivals. “What language does your champion speak?” shouted the Austrian, Kmoch, after his third offer of a draw had been met only with

Sultan’s gentle smile. “Chess” I replied, and so it proved, for in a few moves the Austrian champion had to resign. (See a letter to CHESS from Han Kmoch at the end of this article).

From this time onward Sultan went from strength to strength. He won two more British championships and was also highly successful in international events, both in Team Tournaments and individual contests. His greatest achievement was probably his successful match against Tartakover. He soon put off his native dress in favour of more normal apparel but apart from that he remained to the end the inscrutable Oriental. What ideas, if any lay behind that dark impassive face? It was impossible to say, for all the time I knew him he never spoke of any subject but chess. He gradually acquired a knowledge of English and finally spoke quite well. In order to study the chess magazines he also learned to read, but writing was beyond him. I often wrote his letters for him including some to a girl friend whose acquaintance he had made in Hyde Park. The lady seemed to like them.

By 1933, when he won the championship for the last time, he must have been one of the first half dozen or so best players in the world. The highest honours seemed open to him and then ! – just as suddenly as he appeared, he vanished. His patron, Sir Umar, relinquished his post and returned to India taking Sultan with him, and nothing has been since heard of him. He may be dead, but in that case I think the news would have leaked out. I fancy myself that he can still be seen sitting under a tree in some remote village in the Punjab playing the game of his forefathers. If this is so I wonder if he ever dreams of his five years in the West.

and here is a letter from Hans Kmoch following Winter’s memoirs:

Not that it matters, nor that I would cast any blame on the later William Winter whom I knew as a perfect gentleman. It is only for the sake of curiosity that I ask permission to comment on Winter’s story concerning my game against Sultan Khan.

I never asked Winter or anybody else what language Sultan Khan spoke. Nor did I shout (I never do). Sultan Khan and I had met before. What little conversation there was between us was done in English of which we both had a command sufficient for the purpose.

Winter, being not asked, had no opportunity to reply “Chess” or anything else.

I did not offer a draw three times, nor did Sultan Khan, who never smiled, meet my offers with a smile. Nor again did I resign a few moves later. And ! was not the Austrian Champion (contests have not been held at all in my active time).

Sultan Khan had White: we played a Giuoco Piano. After a small number of moves, probably 18 or so, a position was reached which I considered as fully satisfactory for Black.

I offered a draw so as to gain time for my work as a reporter. (I used to be very strict in never offering a draw to anybody unless my position, to the best of my understanding, was fully satisfactory).

Sultan Kahn accepted my offer outright. The game ending in a draw is a provable fact.

New York, 17th April 1963

Hans Kmoch

(we believe Mr. Kmoch! – Editor)

Sultan Khan-Flohr 3rd match game 1932 Caro-Kann

Defence, Exchange Variation

Here is his Wikipedia entry

Here is an excellent article from chess.com