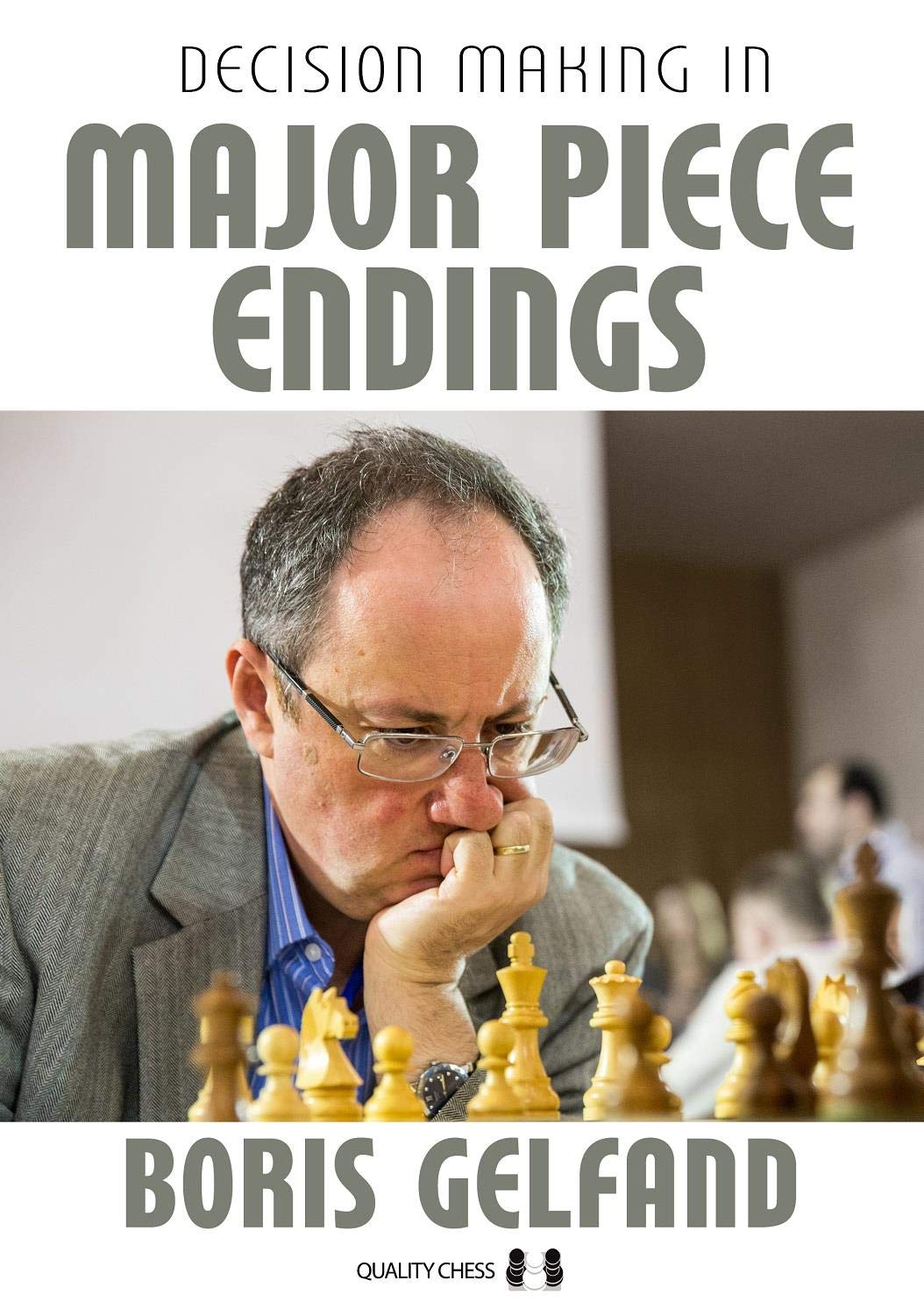

The Power of Defence and the Art of Counterattack in 64 Pictures : Nikola Nestorović and Dejan Nestorović

From Nikola’s web site :

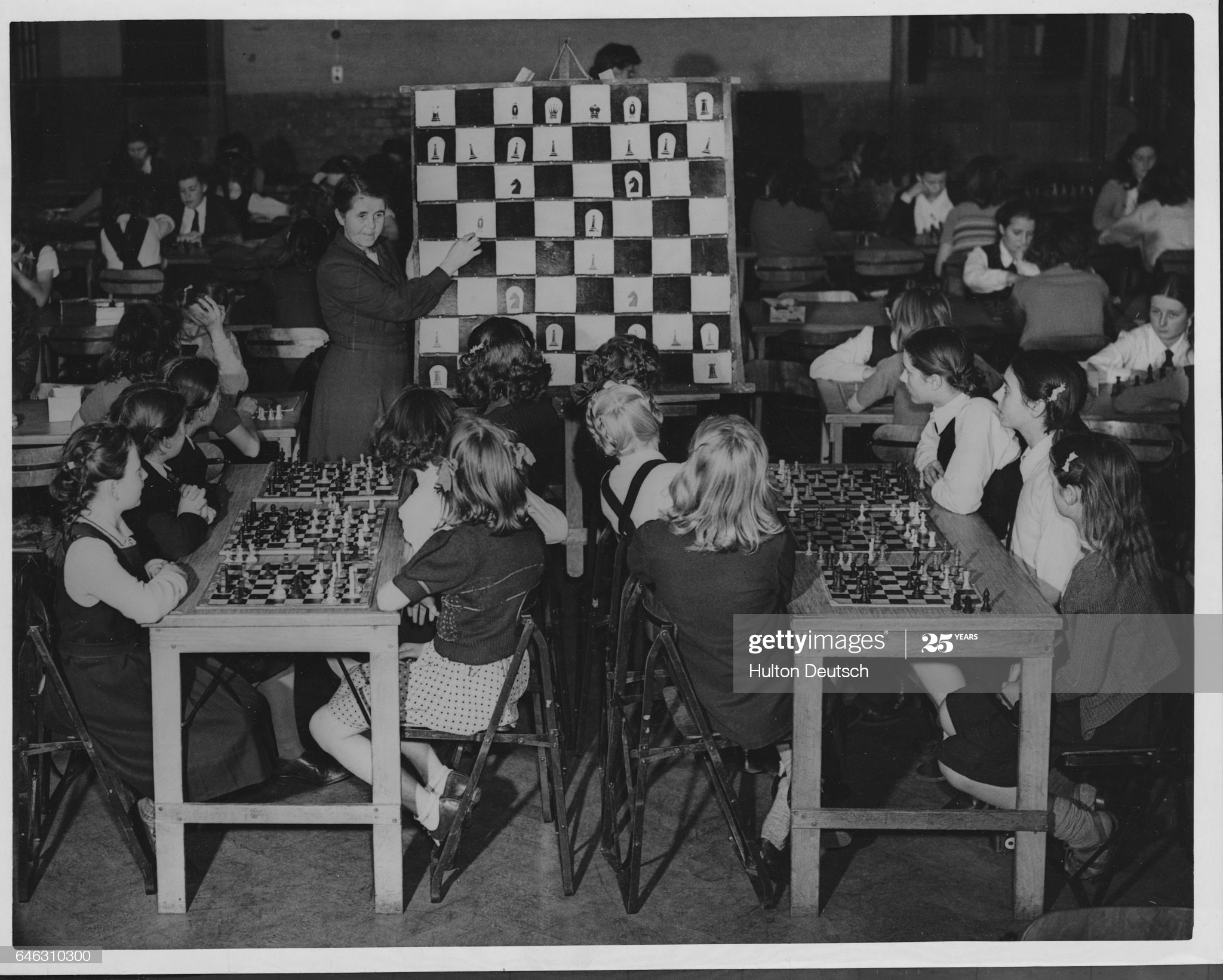

“My name is Nikola Nestorović and I have been playing chess for more than 20 years. During that time I managed to accomplish most of my playing career goals. The most important fact is that I became a Grandmaster at the end of 2015 and officially I became FIDE Chess Trainer in 2018. As I was growing up I realized that I really enjoy teaching so I decided that I am going to pursue that kind of a profession. Whether at school or at home I was always in the mood for teaching others and that feeling was very important in my chess coaching career. The connection between teacher and student need to be professional but friendly because only with this trust student can improve in a special way. So first, I want to make a special connection with my student – and then, chess will be very easy to learn! For years I worked on my special chess materials, so I can adjust my lessons to any type of player! And one very important thing – your age is not important, you can ALWAYS improve your chess play! So, If you love chess and you want to learn and improve in this beautiful game – I am sure that together – we can achieve your (our) goals! I am waiting for you! Cheers! Nikola”

From the publisher’s website :

“A tale of 64 magical squares in 64 shrewdly created pictures. Many a book delved deep into the vast oceans of tactics, positional play and strategy, but very few dared to enter and master a notoriously elusive realm of defence in chess.

In this highly instructive tome the authors tried to accomplish several demanding goals. To uncover many of the secrets that remain hidden so very often, to tackle the most difficult area of chess skill – defence, and finally to teach a great number of ambitious chess-players helping them to improve their knowledge in this important area of chess expertise.

We present you the book by GM Nikola Nestorović, and his father IM Dejan Nestorović with firm belief that you will appreciate many hours of their hard work and devotion to this intriguing topic. The games presented in this tome are both recent and older ones, played by the chess elite and their lower rated peers, but without exception instructive, deeply and diligently analysed for your reading and learning pleasure.

You learned to attack – now it is time to sharpen your defensive tools!”

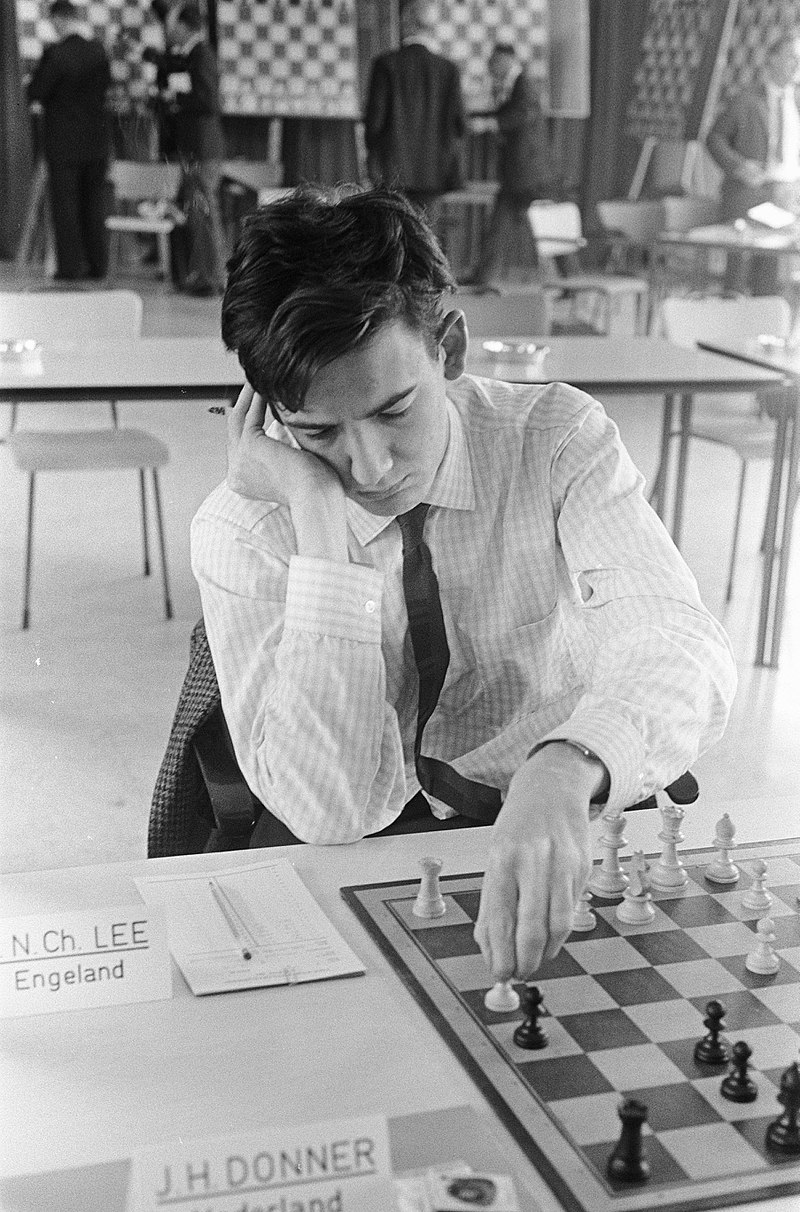

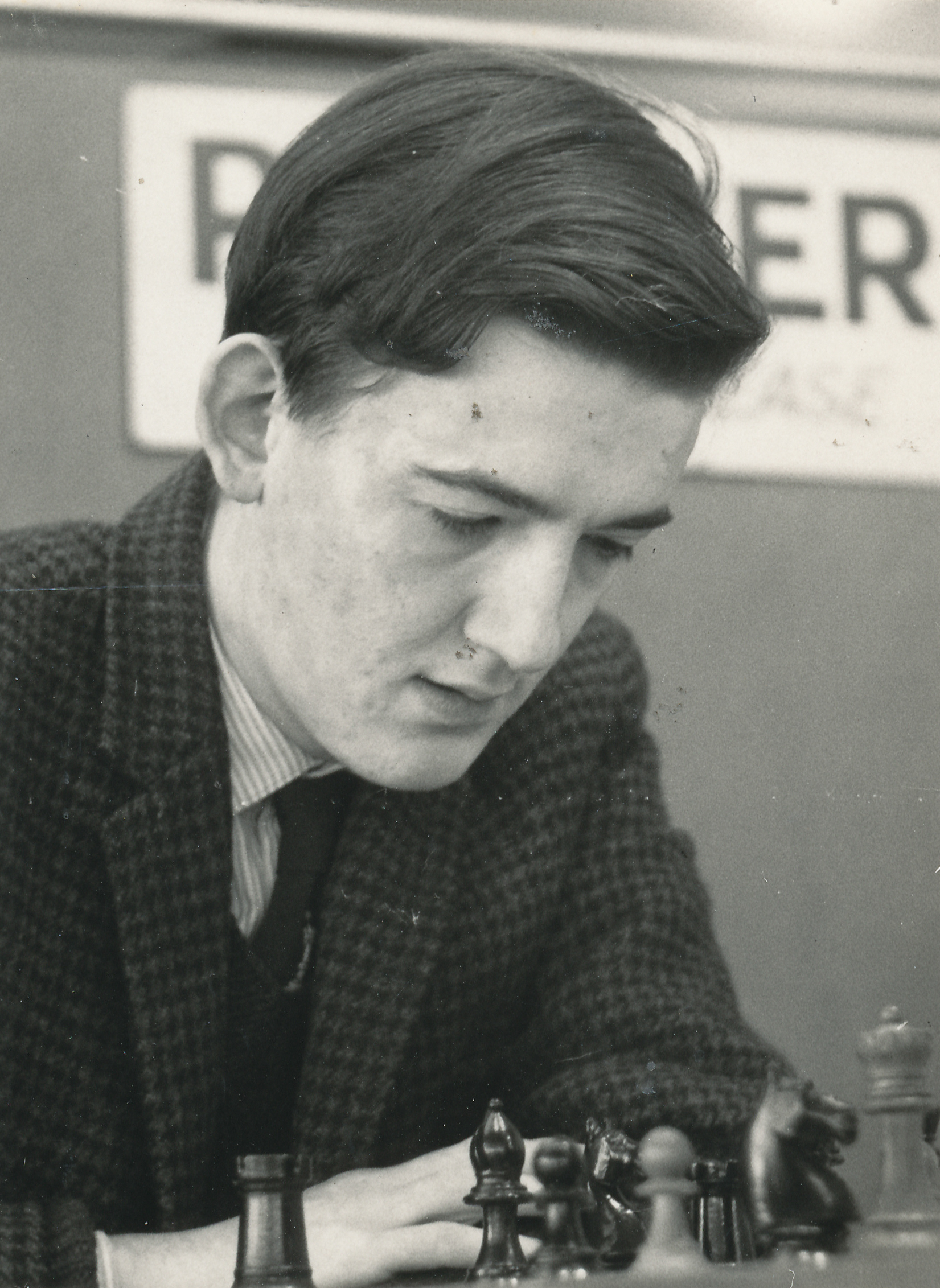

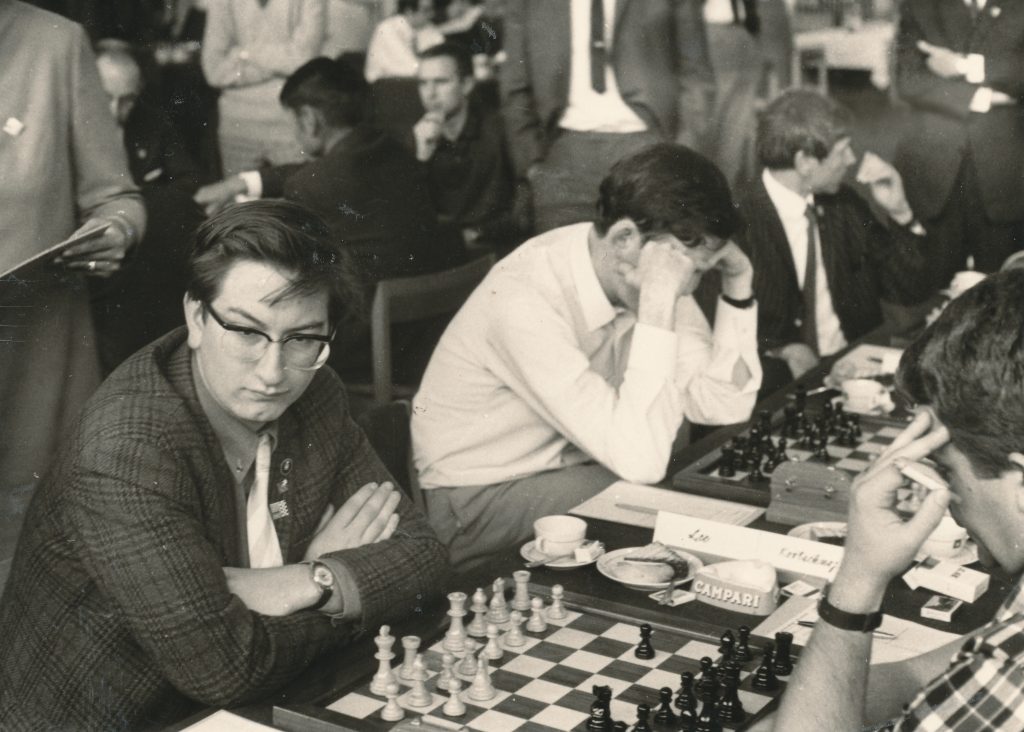

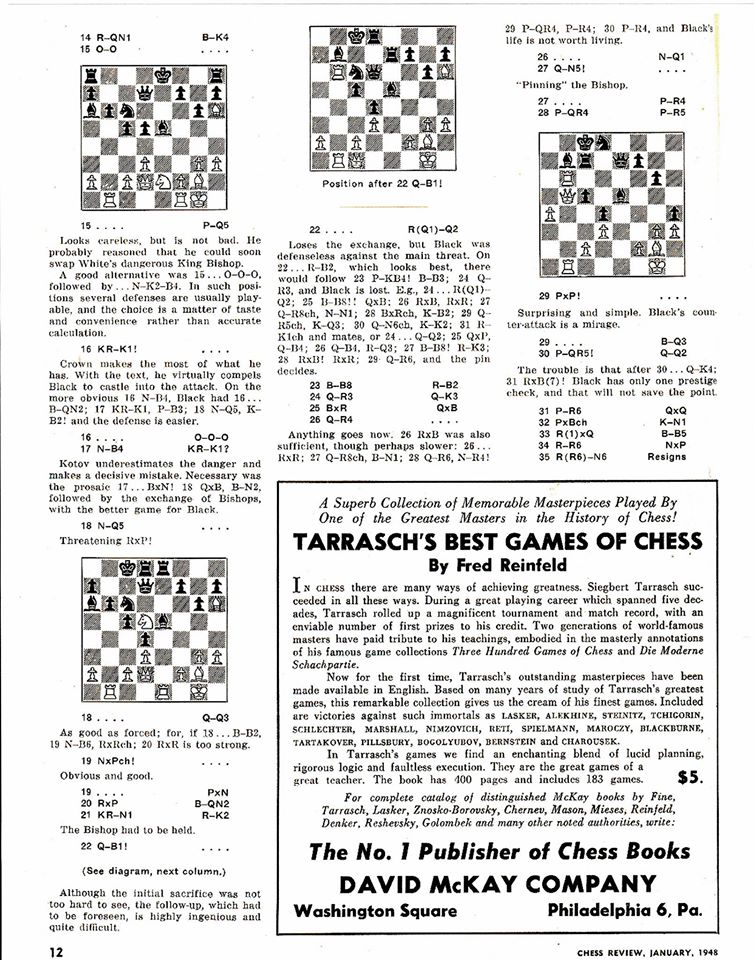

The first thing to notice is that this is a handsome hardback, complete with a bookmark, and enhanced by photographs of some of the players featured within. Unlike the previous book I reviewed from this publisher, it uses orthodox fonts for both text and diagrams.

When turning to the first game you’ll see a game from a tournament that is still, at the time of writing this review, unfinished. This is Grischuk – Alekseenko from the 2020 Candidates Tournament. The first section, Modern gladiators, features 19 games or positions from recent tournaments, working backwards from 2020 to 2017, featuring many of today’s leading players.

Knights of XXI century takes us back from 2016 to 2007 with another 19 examples. Then, Pearls don’t lose their luster offers ten more positions going back to Savon – Tal in 1971. A moment of glory gives us seven specimens from slightly less celebrated players, and finally, From the maker’s mind treats us to nine games from the authors themselves.

This is an advanced book covering a difficult topic, that of defence and counterattack, and probably most suitable for players above, say, 2200 strength. You’ll find a lot of exciting, double-edged games, demonstrating all that is best in contemporary chess. Many of the games feature positional sacrifices, so if you’ve read and enjoyed Merijn van Delft’s recent book, this might be a useful follow-up. But the analysis here is much denser: lots of presumably computer generated tactical variations for you to work your way through.

Let’s look at one of the shorter and simpler examples.

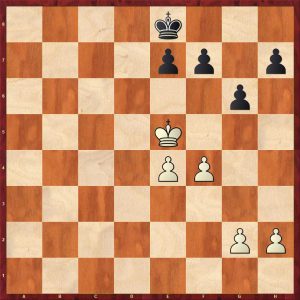

We join the game Kožul – Stević (Nova Gorica 2007) with White about to play his 31st move. (Informator’s house style is to omit capture and check signs: I’m following that here, but using letters for pieces instead of the book’s figurines.)

31. g3

“Kožul is resigned to the fact that he has to wait for his opponent’s mistake in the realisation because Black’s extra pawn on b4 along with excellent placement of his pieces don’t bode well for White.”

31… Rd3?!

“A mistake that wouldn’t have needed to drastically affect assessment and events in the game had the danger alarm made a sound in good time.

“31… Qd3!? After simple exchange of queens Black would have only minor technical problems in the realisation of his material advantage. 32. Qd3 Rd3 33. Rc6 Ba5 34. Rc8 Kh7 35. Kg2 g5 With further strengthening of the position.”

32. Rc8

“The only way to create a chance, of course. White is still waiting for his opponent’s help.”

32… Kh7?

“After Rd3 one could surmise that Stević overlooked his opponent’s threat and that he only expected a passive defence. 32… Rd8! after the rook returned to the eighth rank, the chance for salvation disappeared, at least at this moment.”

33. Ng5!

“A nice tactical stroke which immediately changed the situation on the board. This was an absolute shock for Stević! All of a sudden he had to deal with concrete problems. And as it is usually the case, one mistake follows another.”

33… Kg6

“33… hxg5?? 34. Qh5#”

34. Qe4

“After Qe4 good defence is required in order not to lose the game.”

34… f5?

“Now a fatal error which brings White closer to victory. Black has two responses after which his opponent would be forced to draw.”

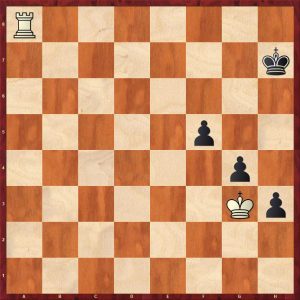

(Now there’s some analysis of Black’s drawing moves Kg5! and Kh5!, along with a diagram after Kh5, which I’ll omit here.)

35. ef6 Kg5 36. fg7!?

“36. Qe5! The safest path to victory. 36… Kg4 37. Qf4 Kh5 38. fg7+-”

36… Bf2

“A good attempt to create a counter-chance. 36… Qb1! The best practical chance. 37. Kg2 Rg3! 38. hg3 Qe4 39. Kh2 Qh7 40. g8Q Qg8 41. Rg8 Kf6 42. f4 There would still be some play here, although it can be said that White only needs to resolve some technical problems in the realisation of his material advantage.”

37. Kg2!

(There’s another diagram here: rather redundant as we’re only two half moves away from the previous one.)

“The game can still be lost for White: 37. Kf2?? Rd2 38. Kf1 Qd1 39. Qe1 Qf3 40. Kg1 Qg2#”

37. Rg3 38. Kf2 1:0

“Dangerous checks have disappeared. Black resigns due to the simple capture of the rook followed by promotion of the pawn to queen. Certainly, the key moments happened in time-trouble which is the period of the game when the side experiencing problems in the position should be concentrated and should seek its chance carefully.

“Kožul seized his chance while for Stević it can be said that he first missed a huge opportunity to win and then when he had to calculate where to go with his king and how o do it, he made incorrigible mistakes and suffered defeat.”

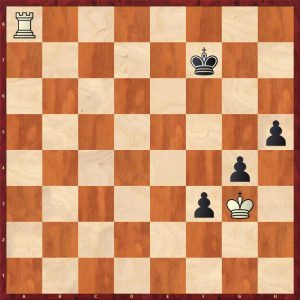

Here’s one of the authors in action in a very recent game: Todorović – N Nestorović (Smederevska Palanka (rapid) 2020).

“The position on the board shows us the moment when White has the opportunity to prevent a counterattack with a simple bc3 or enter calculations by playing tactical Ne8 where, at first glance, he wins material and easily promotes the e-pawn to queen.”

29. Ne8?

“29. bc3! (I’ve omitted the diagram) The simplest move! Now White is threatening to capture the rook on e8 and create the best defensive setup. 29… Qc4! 30. R4e3! After two simple defensive moves, Black’s hope vanishes. 30… Rc7 (30… Re7 31. Qa8! Capturing material.) 31. Qc7 And Black doesn’t have any possibility to create threats. 31… Qa2 32. cd4 Qa1 33. Kd2 Qb2 34. Kd1 Qb1 35. Ke2+-

“The king goes to the part of the board where there are no more checks and so the last threats will disappear.”

29… Qc4!!

(There’s another diagram here.) “The only way to create threats and shift the focus of play to the other side of the board.”

30. Qb8

“The most logical way to defend the white castling.”

(There’s a long note here demonstrating that 30. Nd6!? and 30. Qa5!? both lead to perpetual check, and again there’s a diagram after each of these moves.)

30… cb2 31. Kb2 Qc2 32. Ka1 Qc3

33. Qb2?

“Our desire to win sometimes gets us off the right path. 33. Kb1=

33… Nc2 34. Kb1

(Surely this diagram should be after, rather than before Black’s next move.)

34… Rb6!!

“A phenomenal way to end a counterattack!

“White resigns due to his inability to defend from checkmate!”

35. Qb6 Na3# 0:1

These extracts should give you some idea of the strengths and weaknesses of this book. There’s a lot of great chess here: exciting, creative and imaginative, as well as, as you’d expect in games of this nature, even at the highest level, a lot of mistakes as well. You certainly get a feeling of the inexhaustible riches of our beloved game. The subject of defence and counter-attack is not an easy one to teach, but the main point is well made. If you’re under attack you must meet immediate threats, but, beyond that, you should, if possible, avoid passive defence and look for opportunities to create active counterplay, even if this involves taking risks. Don’t be afraid to consider moves which may not be objectively best but will put your opponent under pressure.

The authors clearly have a keen eye for games of this nature and all readers will enjoy playing through and studying them.

However, you can probably also see some negatives. The translation, while mostly making sense, is a long way below professional standards. The layout of the book is poor and makes the games difficult to follow. You’d certainly need two boards and even then it wouldn’t be easy. There are lots of long tactical variations with embedded diagrams the same size as those in the main text. In some cases the game continuation is in the annotations while the book follows a more interesting line that wasn’t played. It all gets rather confusing, and the translation, along with the lack of capture and check signs, doesn’t help. It’s especially confusing when the actual game continuation is in the notes, while another variation, which would have led to a different result, is given as the main line.

Speaking as a 1900 strength player, I thought the book was pitched rather above me. I’d have preferred annotations with fewer computer generated variations and less verbose prose, and perhaps a puzzle section at the end to reinforce the lessons learnt from the examples, along with an improved layout and a better translation. The van Delft book mentioned above handles a similar subject in a much more appropriate way for players of my level, in terms of a more logical structure and more helpful annotations.

A qualified recommendation, then, for lovers of thrilling tactical games with vacillating fortunes played, mostly, at the highest level.

Richard James, Twickenham 22nd November 2020

Book Details :

- Hardback : 352 pages

- Publisher: Sahovski Chess (aka Chess Informant or Informator) 2020

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: ?

- ISBN-13: ?

- Product Mass : ?

Official web site of Sahovski Chess