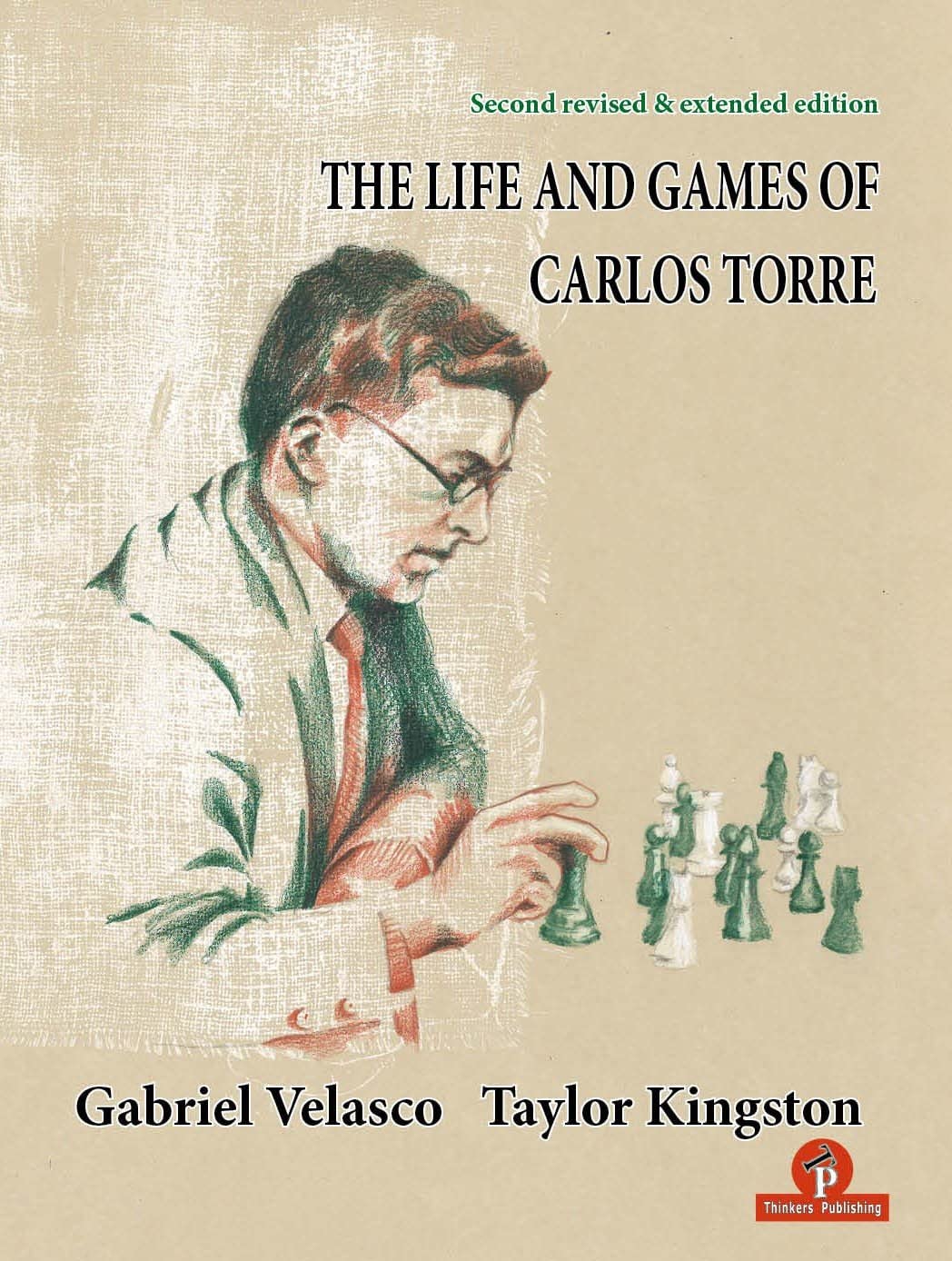

From the Publisher, Thinkers Publishing:

“The Grunfeld Defence is one of the most dynamic openings for Black.

The opening was developed by two famous World Champions, namely Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov.

While theory is far from being exhausted and still developing, our author Grandmaster Milos Pavlovic made a strange case and found new alternatives to battle White’s setups. On top this book cuts through the dense theory that surrounds this opening and establishes a total new repertoire based around consistent strategies, concepts and novelties.

This is a fully revised and seriously extended edition of the original book published in 2017.”

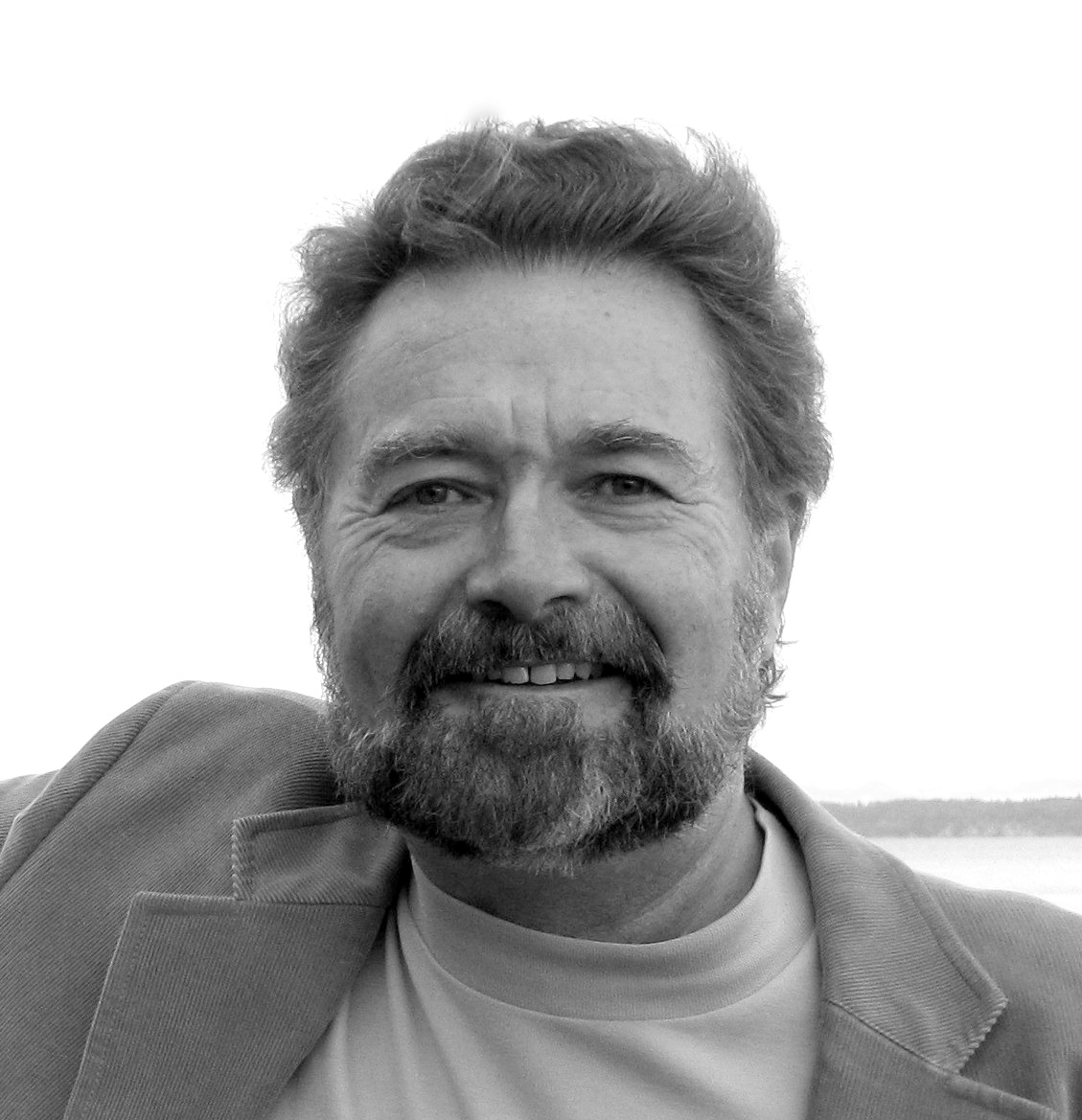

About the Author:

“Grandmaster Milos Pavlovic was born in Belgrade in 1964. He has won many chess tournaments worldwide including becoming Yugoslav Champion in 1992. A well-known theoretician, he has published many well-received chess books and numerous articles in a variety of chess magazines. This is his 14th book for Thinkers Publishing.”

This is the fifth title from Milos Pavlovic that we have reviewed. Previously we have examined: The Modernized Marshall Attack, The Modernized Scotch Game: A Complete Repertoire for White and Black, The Modernized Stonewall Defence and The Modernized Colle-Zukertort Attack

This heavy theoretical book has 14 chapters:

Chapter 1 – Exchange Variation 7.Bc4 – with 11.Rc1

Chapter 2 – Exchange Variation 7.Bc4 – Sidelines

Chapter 3 – Modern Exchange Variation – 8.Rb1

Chapter 4 – Modern Exchange Variation – 7.Be3

Chapter 5 – Modern Exchange Variation – 7.Nf3 c5 – Sidelines

Chapter 6 – Exchange Variation – Alternatives on move 7

Chapter 7 – Alternatives after 4.cxd5 Nxd5

Chapter 8 – 5.Qb3 – The Russian System

Chapter 9 – Early Qa4+

Chapter 10 – 4.Bf4

Chapter 11 – 5.Bg5 lines

Chapter 12 – 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.h4

Chapter 13 – 4.e3

Chapter 14 – Anti-Gruenfeld 3.f3

This theoretical tome is certainly a comprehensive guide to the contemporary opening theory of the Gruenfeld Defence from black’s point of view . It is certainly a repertoire book for black. There are pithy paragraphs that explain the ideas behind the moves but these are few and far between the dense variations. In my opinion, it is aimed at active 2000+ tournament players. This is in no way a criticism, but an inexperienced player wanting to learn the opening with just this book may be lost in a sea of variations without a mentor and/or a Gruenfeld primer book to explain the ideas.

In terms of layout, the book is easy to read, has sufficient accompanying text and plenty of diagrams to be able to get a good grasp of the lines. The chapter structure is logical with a strong bias toward the contemporary lines played at the top. This slant is perfectly reasonable as trendy lines trickle down to all levels.

This review will briefly summarise the suggested repertoire and highlight a few interesting variation choices from the author.

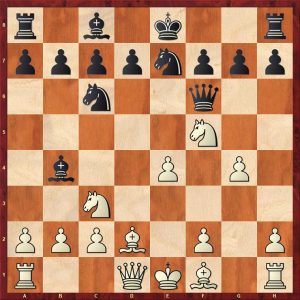

Chapter 1 covers the “old” Exchange after these moves:

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 5.e4 Nxc3 6.bxc3 Bg7 7. Bc4 c5 8.Ne2 Nc6 9.Be3 0-0 10.0-0 b6 11.Rc1

The author has recommended the modern 10…b6 which is the key line now. This supersedes the old 10…Qc7 of Fischer-Spassky days.

The last line covered in this chapter is 11…Bb7 12.Bb3!?

The main move here is 12…cxd4 but the author suggests 12…Na5!? as an improvement. 13.d5 e6 14.c4 exd5 15.exd5 Re8

The author gives 16.h3 (Stockfish suggests the irritating 16.Ba4 when 16…Re5 17.Qd3 17…a6 looks to equalise) 16…Bc8 a neat manoeuvre to rearrange black’s minor pieces to better posts 17.Ng3 Nb7 18.Qd2 Nd6 =

Back to the main line after 12…cxd4 13.cxd4 Na5 14.d5 reaching this position:

I like the author’s didactic comment on this position, explaining white’s positional idea with 14.d5:

“That’s the idea. White doesn’t care about his bishop on b3; he wants to trade the dark-squared bishops on d4 and play a middlegame with a strong knight against a poor bishop on b7”

14…Qd6 15.Re1!?N (15.Bd4 Ba6! ridding black of his poor bishop by exploiting the pin on white’s e2 knight which equalises as played by Gruenfeld expert Grischuk)

15…Rac8 16.Rxc8 (16.Qd2 Nxb3 17.axb3 f5! striking in the centre to equalise) 16…Rxc8 17.Bd4 Ba6 activating the prelate 18.Bxg7 Kxg7 19.Nd4!

White has achieved his goal of centralising his horse although black has activated his bishop and rook. White’s plan is now to advance the h-pawn: black must not faff about. Hence 19…Qb4 20.h4 Qc3! 21.h5 Bd3 with equality.

Chapter 2 covers the “sidelines” other than 11.Rc1 from Diagram 1 above. Sidelines is a slight misnomer as these lines are all important.

The three moves covered are the solid 11.Qd2, the greedy 11.bxc5 and the aggressive 11.h4.

After 11.Qd2 a main line continuation with typical Gruenfeld moves is: 11…Bb7 12.Rad1 cxd4 13.cxd4 Rc8 14.Bh6 Na5! 15. Bxg7 Kxg7 16.Bd3 Nc4 17.Bxc4 Rxc4 reaching a balanced tabiya position where both sides have their trumps:

The greedy 11.bxc5 is obviously critical as it wins a pawn but black has good positional compensation.

After 11…Qc7! the obvious 12.cxb6 axb6 winning a pawn is dismissed briefly with a couple of variations. I do not disagree with the author that this line gives white no advantage, but black players should study this line in more detail, as it is common response from white players.

After 11…Qc7 12.Nd4 Ne5 13.Nb5 Qb8! reaches a key position:

There are two critical lines, the greedy 14.Bd5 and the more popular, solid 14.Be2

Both lines are covered in detail showing adequate play for black to equalise.

11.h4 is extremely interesting and in the author’s opinion, the critical test of 10…b6.

Black should respond 11..e6 12.h5 Qh4

White has two main moves here, the reviewer will show a pretty line after the natural 13.hxg6 hxg6 14.f3 cxd4 15.cxd4 Rd8 16.Qd2

Black looks to be in trouble with 17.Bg5 threatened, however black calmly develops with 16…Bb7 offering a poisoned exchange, after 17.Bg5 17…Qh5 18.Bxd8 loses, after 18…Rxd8, the two bishops and white’s gapping black squares lead to defeat, for example 19.d5 Ne5 20.Rac1 Nxc4 21.Rxc4 Ba6 22.Ra4 Bh6 wins

13.Qc1 is much more dangerous, buy the book to find out how black neutralises this enterprising continuation.

Chapter 3 is all about the Modern Exchange variation with 8.Rb1.

As the author points out, this is a well-known weapon, and for a while, a few decades ago, created massive problems for the Gruenfeld opening. Its fangs have now been drawn; at the moment there are at least two decent variations that equalise for black. Several recent Gruenfeld books such as those by Delchev and Kovalchuk recommend 8…0-0 9.Be2 Nc6 (with 13…Bc7!) which has been known for a while to be perfectly viable for equality. The reviewer thinks that line is perhaps simpler for black, but both that line and the author’s suggestion require a significant amount of theoretical knowledge.

After 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 5.e4 Nxc3 6.bxc3 Bg7 7.Nf3 c5 8.Rb1 0-0 9.Be2 cxd4 10.cxd4 Qa5+

Pavlovic recommends the “old fashioned” Qa5+ taking the a2 pawn.

11.Qd2 is rather anaemic, leading to an equal ending.

After 11.Bd2!? Qxa2 12.0-0 Bg4! Quick development to put pressure on the d4 pawn, not worrying about the b7 pawn.

13.Rxb7 leads to equality although black has to be careful.

Now 13…Bxf3 14.Bxf3 Bxd4 15.e5 Na6! 16.Rxe7 Rad8 is ok for black, the pressure on the d-file makes it hard for white to generate a serious initiative.

The last two sub-variations in this chapter are in a very sharp line:

The author gives two lines for black to achieve equality: 14..g5! and 14…a5! The fact there are two good lines indicates that the line is clearly satisfactory for black.

Chapter 4 covers 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 5.e4 Nxc3 6.bxc3 Bg7 7.Be3 c5

This is a large chapter and one of the major white systems. There are many subtleties in the placing of white’s rook on c1 or b1. The author has 15 principal lines.

This is the position in the 10.Rb1 line viz:

Pavlovic recommends two different variations for black here:

- 10…cxd4 going into the queenless middlegame

- 10…a6 waiting and preventing Rb5

After 10…a6 white’s main move is 11.Rc1: white argues that 10…a6 has weakened black’s queenside.

Black again has two alternatives:

- 11…cxd4 going into the queenless middlegame

- 11…Bg4 keeping the queens on

If instead of 10.Rb1 white plays 10.Rc1, Pavlovic unequivocally recommends 10…cxd4 11.cxd4 Qxd2+ as this ending is definitely ok for black.

White can play Be3 and Qd2 before Nf3:

In this, the recommended line is to exchange queens with 10…cxd4 11.cxd4 Qxd2+ which lead to an interesting ending where black is holding his own.

Chapter 5 covers 7.Nf3 c5 sidelines

These variations include:

- 8.h3

- 8.Be2

- 8.Bb5+

I have never faced 8.h3 and have rarely met 8.Bb5+.

On the other hand, I have faced 8.Be2.

There is an exciting exchange sacrifice in this line viz:

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 5.e4 Nxc3 6.bxc3 Bg7 7.Nf3 c5 8.Be2 Nc6 9.d5 (9.Be3 is inept 9…Bg4! and black is at least equal) 9…Bxc3+ 10.Bd2 Bxa1 11.Qxa1 Nd4 12.Nxd4 cxd4 13.Qxd4

Black has two moves, the obvious 13…f6 preserving the material advantage and the probably safer 13…0-0

After 13…f6, the author is of the opinion that 14.Bc4! is exciting and dangerous

After 13…0-0 white can regain the exchange with the obvious 14.Bh6 but loses time and forfeits castling rights after 14…Qa5+ 15.Kf1 f6 16.Bxf8 Rxf8 – this is equal

14.0-0 is more ambitious when 14…Qb6! 15.Qa1!? Bd7 16.Bh6 f6 17.Bxf8 Rxf8 18.Rb1 (18.Qb1 leads to a drawn bishop endgame) 18…Qc7 leads to approximate equality

Chapter 6 covers alternatives on move 7 in the Exchange Variation:

The book shows the following four alternatives:

- 7.Ba3

- 7. Bg5

- 7.Bb5+

- 7.Qa4+

These moves are rare: in full length games, the reviewer only recalls facing 7.Ba3 once, 7.Bg5 once and has never faced the other two.

Pavlovic handles these lines well. It is interesting that his recommendation against Bb5+ is to play 7…c6 and then play for e5. Many books have suggested rapid queenside expansion for black.

Chapter 7 covers alternatives after 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5

The two lines covered are:

- The exotic 5.Na4

- The super trendy 5.Bd2 which is played at all levels

After 5.Na4

Pavlovic recommends the dynamic 5…e5 striking in the centre which is the top engine suggestion. This draws the teeth of this extravagant knight move. (5…Nf6 6.Nc3 Nd5 7.Na4 has been played as a silly repetition draw).

5.Bd2 is a different kettle of fish, the idea is to recapture the knight on c3 with the bishop:

The author recommends a straightforward approach from black viz:

5…Bg7 6.e4 Bxc3 7.Bxc3 0-0 maintaining flexibility & waiting to see which setup white adopts.

The two main lines here are 8.Bc4 and 8.Qd2 which the author covers in great detail. Shirov’s idea of 8.h4!? is covered very briefly with a variation given that is far from best play for white.

In the reviewer’s opinion this is a very important chapter, as this variation is so popular to avoid main line theory. Ironically, this setup now has a large body of practice.

Chapter 8 covers the Russian System. Pavlovic recommends the Prins Variation which is 7..Na6.

As the author points out, black can play this variation against many of white’s tricky move orders involving Qb3. The Prins Variation was often used by Garry Kasparov, so has an excellent pedigree. The reviewer loves this part of the repertoire as black avoids the Hungarian 7…a6 and 7…Nc6 which are both decent systems but very topical. Avoiding the most popular lines does have its advantages.

Chapter 9 covers Qa4+ ideas which is a short chapter. Qa4+ ideas are usually used as a move order trick to get black out of main line theory.

There are two really important positions in this chapter.

After 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.Qa4+ Bd7 6.Qb3 dxc4 7.Qxc4 0-0 8.Bf4

and after 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.Qa4+ Bd7 6.Qb3 dxc4 7.Qxc4 0-0 8.e4

White has played a move order to disrupt black’s development by giving him an extra move of Bd7. However, black can exploit the bishop on d7, to play 8…b5! in both positions gaining good play with this energic pawn sacrifice.

Chapter 10 covers the 4.Bf4 line which is very popular at club level and was played by Karpov against Kasparov.

The author gives three major sub-variations in the main line:

- 14.g4

- 14.Nxe4

- 14.Nd5

All these lines are well known and black has equality with care.

Pavlovic suggests a really interesting idea early in one of the main lines which I had not seen before:

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Bf4 Bg7 5.e3 c5 6.dxc5 Qa5 7.Rc1 Nbd7!?

Buy the book to find out about this excellent idea.

The idea is allied to another line:

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.Bf4 0-0 6.e3 c5 7.dxc5 Ne4! 8.Rc1 Nd7!

Chapter 11 is all about Bg5 ideas which occur on move 4 or 5.

Against 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.Bg5, Pavlovic suggests the traditional 5…Ne4 and against 4.Bg5 he also approves of the knight move to e4.

The solid repertoire here is pretty well known and respectable.

Chapter 12 is a brief chapter on 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.h4!?

The author recommends 5…c6 which is solid and sensible. The author states this is an important new line: it has been around for decades.

After these sensible developing moves 6.cxd5 cxd5 7.Bf4 0-0 8.e3 Nc6 9.Be2 Bg4 resembles a Slav Defence.

White has absolutely nothing here. A draw was soon agreed.

Chapter 13 is about 4.e3 which is a solid continuation, not generally played by the top players. It covers a topical line:

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.e3 Bg7 5.cxd5 Nxd5

Now white draws the black queen into the centre with 6.Nxd5 Qxd5 only to manoeuvre his other knight to gain time 7.Ne2 0-0 8.Nc3 8…Qd6

But it’s all too slow really. After 9.Be2 black can play 9…c5! sacrificing a pawn for loads of play 10.Nxe4 (10.d5 is the main line but leads to nothing for white) 10…Qc7 11.Nxc5 e5 12.0-0 Rd8 13,Nb3 Nc6 reaching this position:

White can retain his extra pawn with 14.d5, but 14…e4! gains space and after 15.Qc2 Rxd5 16.Qe4 Be6 black has excellent play for a pawn.

The author fails to cover 6.Be2:

This is a solid line that can lead to a reversed Queen’s Gambit, Tarrasch after 6…c5 7.0-0 cxd4. I have faced this as black, against an an IM, so perhaps it should have been covered. Of course, the author has to make a decision on what to include: as this is not a fashionable line, I can understand why the line was omitted.

The final chapter covers 3.f3, a popular anti-Gruenfeld system.

The author recommends the “old” main line with 3…d5 which some authors have eschewed in favour of other systems such as 3…c5 transposing into a kind of Benoni or simply going into a King’s Indian Defence.

The key tabiya is this:

The analysis given by the author is an excellent coverage of all the critical lines from this position and happens to very largely agree with my own investigations.

Here is one fascinating endgame that results after 16.d6 e4! 17.fxe4 Ng4 18.Bg5 Qe8 19.Nf3 Rf7! 20.Qe1 Bxc3! 21.bxc3 Na4 22.Rc1 Nc5 23.Bc4 Be6 24.Bxe6 Qxe6 25.Be7 Nd3 26.Qd2 Nxc1 27.Ng5 Qxa2+ 28. Qxa2 Nxa2 29.Nxf7 Nxc3+ 30.Ka1 Kxf7 31.d7 Ra8 32.d8Q Rxd8 33.Bxd8 Nxe4 34.Rxb7 Ne3 35.Rb2 Kd5

This is a draw as white’s rook and king are passive. This occurred in a correspondence game and the reviewer has had it in an on-line blitz game: white allowed a perpetual with the two knights in a few moves.

The only major variation that has been missed from the book is the Fianchetto Variation which is pretty popular as a solid, positional line. In the reviewer’s last game with the Gruenfeld, he did indeed face a Fianchetto Variation. This is a significant omission but does not spoil an excellent publication on the Gruenfeld Defence.

The reviewer notes a fair few typos in the book.

FM Richard Webb, Basingstoke, Hampshire, 12th May 2024

Book Details :

- Hardcover : 404 pages

- Publisher:Thinkers Publishing; 2nd edition (2 May 2024)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 9464201967

- ISBN-13: 978-9464201963

- Product Dimensions: 17.78 x 3.81 x 24.77 cm

Official web site of Thinkers Publishing