We remember Jacob Henry Sarratt who died 201 years ago today (November 6th) in 1819.

Chess historians will, of course, be familiar with JHS but the name is (probably) not well known outside these exalted circles.

Possibly his most obvious contribution to chess in England was in 1807 when he influenced the result of games that ended in stalemate. You may not know that in England prior to 1807 a game that ended in stalemate was recorded as a win for the party who was stalemated. JHS was able to encourage various major chess clubs so that the result be recorded as a draw. Much endgame theory would be different if it wasn’t for JHS !

Outside of chess, JHS was an interesting chap :

The content below has been copied (and we have corrected a number of typos along the way) from http://www.edochess.ca/batgirl/Sarratt.html

Also, http://billwall.phpwebhosting.com/articles/Sarratt.htm is worthy of consultation.

“Jacob Henry Sarratt, born in 1772, worked primarily as schoolmaster but was much better known for his advocations which, of course, included chess.

After Philidor’s death, Verdoni (along with Leger, Carlier and Bernard – all four who co-authored Traité Théorique et Pratique du jeu des Echecs par une Societé d’ Amateurs) was considered one of the strongest players in the world, especially in England. Verdoni had taken Philidor’s place as house professional at Parsloe’s. He mentored Jacob Sarratt until he died in 1804. That year Sarratt became the house professional at the Salopian at Charing Cross in London and most of his contemporaries considered him London’s strongest player.

There he claimed the title of Professor of Chess while teaching chess at the price of a guinea per game.

By any measure Surratt was not a particularly strong player, but he was able to maintain the illusion that he was by avoiding the stronger players as he lorded over his students who didn’t know better.

Sarratt’s most important contribution to chess was that he mentored William Lewis who in turn mentored Alexander McDonnell.

Surratt had a strange notion that chess culminated in the 16th century and that everything since then had been a step backwards. This odd notion had a positive side. Philidor was the darling of the English chess scene. Almost all books at that time were versions of, or at least based on, Philidor’s book. Surratt at least kept open the possibility that there were ideas beyond those of Philidor.

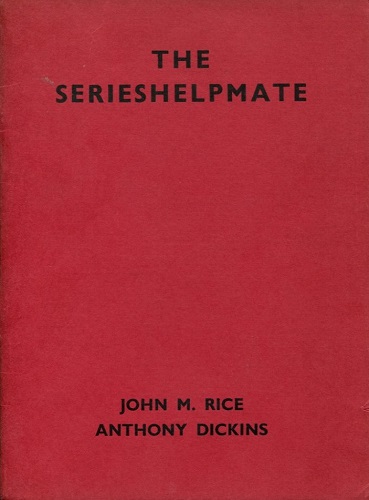

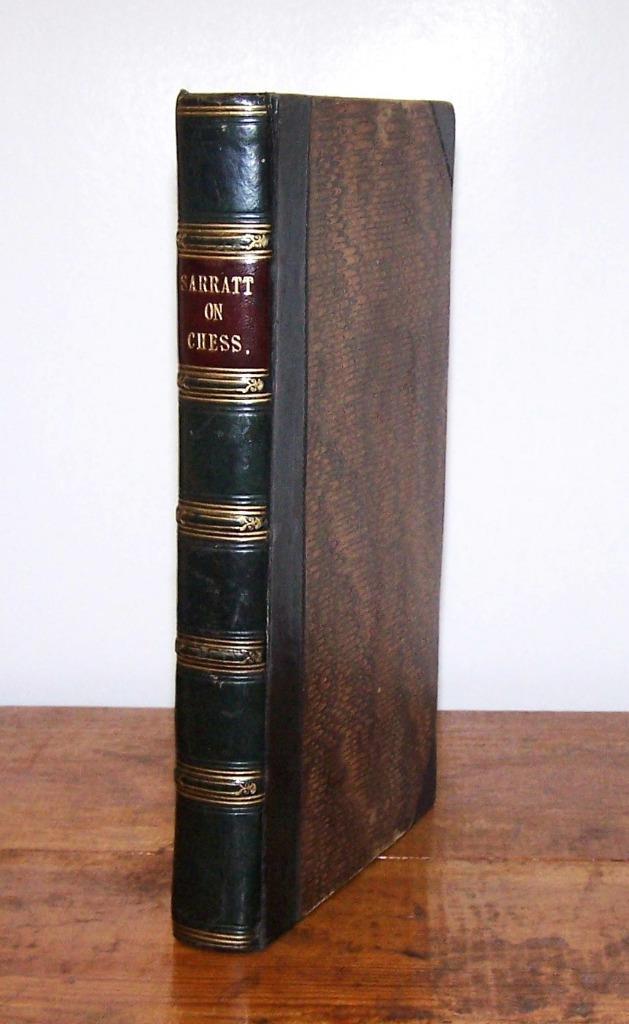

In 1808, true to his role as a teacher, Surratt published his Treatise on the Game of Chess, a book that mainly concentrated on direct attacks on the king which he lifted from the Modense writers.

He translated several older writers whom he admired (though his translations are not considered particularly good):

The Works of Damiano, Ruy Lopez and Salvio in 1813.

The Works of Gianutio and Gustavus Selenus in 1817.

In 1921 a posthumous edition of his Treatise, A New Treatise on the Game of Chess, was published. This copy covered the game of chess as a whole and was designed for the novice player. It also contained a 98 page analysis of the Muzio Gambit

In addition to his chess books, Surratt also published

[i]History of Man in 1802,

A New Picture of London[/i] in 1803

He translated Three Monks!!! from French in 1803 and Koenigsmark the Robber from German in 1803.

His second wife, Elizabeth Camillia Dufour, was also a writer. In 1803 (before they were married, which was 1804), she published a novel called Aurora or the Mysterious Beauty.

They were married the following year. His first wife had died in 1802 at the age of 18. Both his wives were from Jersey.

Contrary to what one might expect, Sarratt has been described tall, lean and muscular and had even been a prize-fighter at one point. He had also bred dogs for fighting. He was regarded as a very affable fellow and very well-read but with limited taste (Ed : surely this applies to everyone ?)

William Hazlitt, in his essay On Coffee-House Politicians wrote:

[Dr. Whittle] was once sitting where Sarratt was playing a game at chess without seeing the board… Sarratt, who was a man of various accomplishments, afterwards bared his arm to convince us of his muscular strength…

Sarratt, the chess-player, was an extraordinary man. He had the same tenacious, epileptic faculty in other things that he had at chess, and could no more get any other ideas out of his mind than he could those of the figures on the board. He was a great reader, but had not the least taste. Indeed the violence of his memory tyrannised over and destroyed all power of selection. He could repeat [all] Ossian by heart, without knowing the best passage from the worst; and did not perceive he was tiring you to death by giving an account of the breed, education, and manners of fighting-dogs for hours together. The sense of reality quite superseded the distinction between the pleasurable and the painful. He was altogether a mechanical philosopher.”

Somewhere along the way there must have come about a complete reversal of his fortunes because Surratt died impoverished in 1819, leaving his wife destitute. But the resilient Elizabeth Sarratt was able to support herself by giving chess lessons to the aristocracy of Paris.

She must have been very well liked. In 1843 when she herself became old and unable to provide for herself, players from both England and France took up a fund to help her out. She lived until 1846.

From The Oxford Companion to Chess (OUP, 1984 & 1992) by Hooper & Whyld :

Reputedly the best player in England from around 1805 until his death. As a young man he met Philidor. Subsequently he developed his game by practice with a strong French player Hippolyte du Rourblanc (d. 1813), with whom he had a long friendship dating from 1798, and with Verdoni, Sarratt’s first important contribution to the game was in connection with the laws of chess: he persuaded the London club, founded in 1807, to accept that a game ending in stalemate should be regarded as a draw and not as a win for the player who is stalemated. He became a professional at the Salopian coffee house at Charing Cross, London,

and in 1808 wrote his Treatise on the Game of Chess.

This, largely a compilation from the work of the Modenese masters, advocated that players should seek direct attack upon the enemy king, a style that dominated the game until the 1870s. An Oxford surgeon, W. Tuckwell, wrote that he learned chess ‘from the famous Sarratt, the great chess teacher, whose fee was as a guinea a lesson’. Lewis, who played many games with Sarratt from 1816, wrote in 1822 (after he had met both Deschapelles and Bourdonnais) that Sarratt was the most finished player he had ever met, Sarratt translated the works of several early writers on the game, making them known for the first time to English readers: The Works of Damiano, Ruy Lopez and Selenus (1813) and The Works of Gianutio and Gustavus Selenus (1817).

He died impoverished on 6 Nov. 1819 after a long illness during which he was unable lo earn a livelihood by teaching. Instead he wrote his New Treatise on the Game of Chess published posthumously in 1821, This is the first book to include a comprehensive beginner’s section: in more than 200 pages Sarratt teaches by means of question and answer. Another feature is a 98-page analysis of the Muzio gambit :

Had it been Sarratt’s ambition to become a chess professional there would have been scant opportunity during the lifetime of Philidor and Verdoni. A tall, lean, yet muscular man, sociable and talkative, he seems in his younger days to have had interests of a different kind, among them prize fighting and the breeding of fighting dogs. Hazlitt, who met Sarratt around 1812 wrote ‘He was a great reader, but had not the least taste. Indeed the violence of his memory tyrannised over and destroyed all power of selection. He could repeat Ossian by heart, without knowing the best passage from the worst.’

Sarratt’s early publications were History of Man (1802): translations of two Gothic novels, The Three Monks!!! (1803), from the French of Elisabeth Guénard (Baronne de Méré) , and Koenigsmark the Robber (1803), from the German of R. E. Raspe; A New Future of London (1803), an excellent guide that ran to several editions, the last in 1814, When war broke out with France in 1803 Sarratt became, for a short period, a lieutenant in the Royal York Mary-le-Bone Volunteers and published Life of Bonaparte * a propaganda booklet detailing Napoleon’s alleged war crimes, and warning of the desolation that would follow if he were to invade.

Not long after the birth of his second child in 1802 Sarratt’s wife died and in 1804 he married a Drury Lane singer, Elisabeth Camilla Du four. Tt would be difficult to find a more accomplished, a more amiable, or a happier couple than Mr and Mrs Sarratt’ – Mary Julia Young, Memoirs of Mrs Crouch (1806), Mrs Sarratt too was a writer contributing tales to various journals and publishing Aurora or the Mysterious Beauty (1803), a translation of a French novel. She survived her husband until 1846, ending her days giving chess lessons to the aristocracy in Paris. In 1843 Louis-Philippe and many players from England and France subscribed to a fund on her behalf. ”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (Robert Hale, 1970 & 1976), Anne Sunnucks :

“Self-styled ‘Professor of Chess’, Sarratt was the first professional player to teach the game in England. He was the author of a A Treatise on the Game of Chess, The (1808), The Works of Damiano, Ruy Lopez and Salvio (1813), The Works of Gianutio and Gustavas Selenus (1817) and a New Treatise on the Game of Chess (1821).

There is no record of Sarratt’s date or place of birth, He began his career as a schoolmaster and later taught chess at Tom’s Coffee House, Cornhill, London, and at the London Chess Club, and was in his day considered to be the strongest player in London.”

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (Batsford, 1983), Harry Golombek OBE :

“Leading English player of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Famed in his day as a teacher and author. Sarratt adopted the title of ‘Professor of Chess’, His writings include A Treatise on the Game of Chess, London 1808, The Works of Damiano, Ruy Lopez and Salvio (1813).

Sarratt is usually credited with introducing into England the Continental practise of counting a game ending in stalemate as a draw. (RDK)”

Some games by Jacob Henry Sarratt: