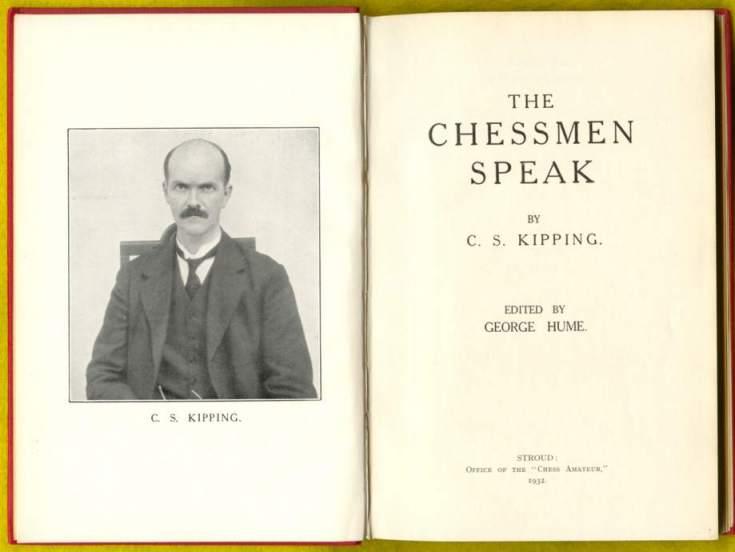

BCN remembers Cyril Kipping who passed away in Walsall on February 17th 1964 at the age of 72.

Cyril Henry Stanley Kipping was born on Saturday, October 10th, 1891 in 7 Milborne Grove, South Kensington, London, SW10 9SN.

His parents were Frederick Stanley Kipping (28) and Lillian Kipping (24, née Holland) : they married in 1888. Cyril was baptised on May 8th, 1892 in West Brompton, London. Frederick died on 30 April 1949 in Pwllheli, Caernarvonshire, at the age of 85 and Lilian passed away on 4 September 1949 in Pwllheli, Caernarvonshire, at the age of 82.

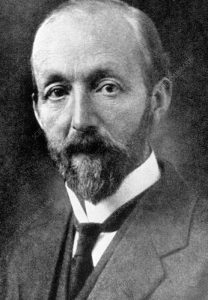

Frederick was Professor of Chemistry at The University of Nottingham. He undertook much of the pioneering work on silicon polymers and coined the term silicone. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1897.

In the 1901 census the family lived at Clumber Road West, Nottingham and brother Frederick Barry Kipping was born on April 14th 1901 and his sister Kathleen Esme was born on 3 May 1904 was also born in Nottingham. Kathleen died on 30 August 1951 in Pwllheli, Caernarvonshire.

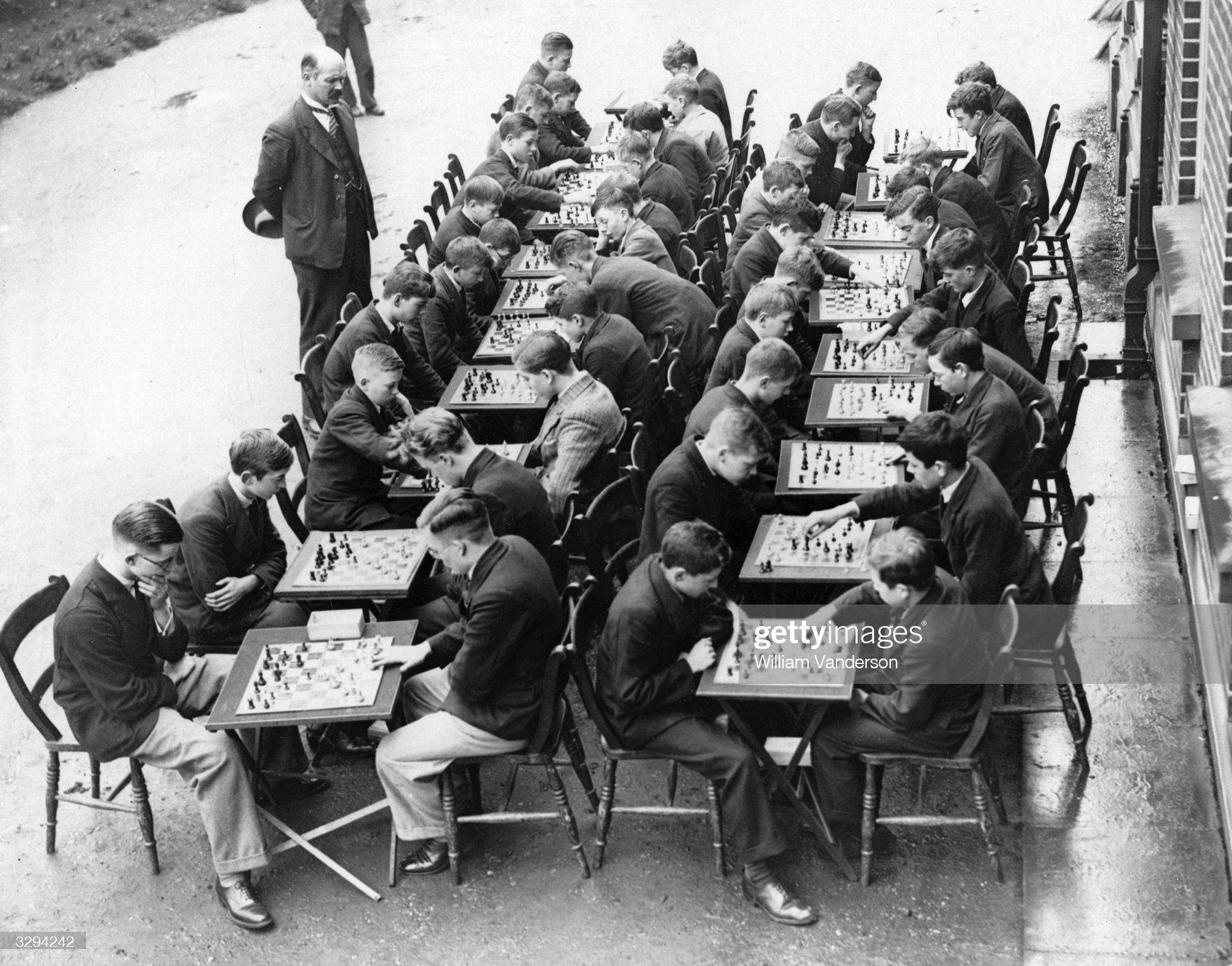

In 1902 Cyril started at Nottingham High School excelling in mathematics and science and in 1906 he obtained the Oxford and Cambridge Board’s Lower Certificate.

On March 2nd 1908 the Sheffield Daily Telegraph published a matriculation list for London University and CHSK was listed as being in the second division from Nottingham High School. Following that in 1909 Cyril obtained a Oxford and Cambridge Higher Certificate.

As of the 1911 census the household now included Cyril’s maternal Grandmother, Florence Holland (59) plus a parlourmaid, a housemaid, a cook and a nurse. Cyril was recorded as being a 19 year old science student and they lived at 40, Magadala Road, Nottingham which appears to have been replaced by residential flats. Curiously the address on the Census record was obscured by green insulation tape but insufficiently for it to readable.

According to Stephen C. Askey

“He left school in July 1910 and went to Trinity Hall in Cambridge where he read for the National Sciences Tripos. He played tennis for his college and launched into the composition of chess problems (1).

He obtained a First in Part I of the Tripos in 1912, a First in Part II in 1913, and was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Arts on 7 June 1913. He began researching in organic chemistry at Cambridge, but in September 1914 decided instead to take a teaching appointment at Weymouth College.”

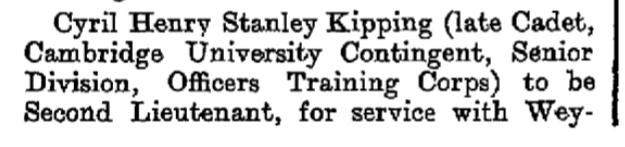

In 1914 The London Gazette announced that Cyril was promoted within the Chaplain Department of the British Army to Second Lieutenant with a service number of 10940.

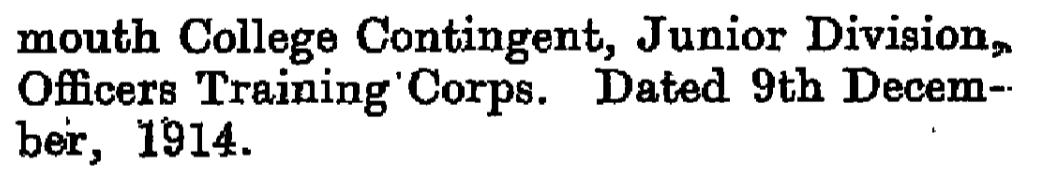

On December 23rd 1914 The London Gazette announced the following :

and

On the 9th October 1918 The London Gazette announced :

Again, According to Stephen C. Askey :

“In January 1919 he took his Master of Arts degree at Cambridge, and joined the teaching staff of Bradfield College in Berkshire. But by the summer of that year he became an assistant master at Pocklington School in Yorkshire, where he spent five happy years.

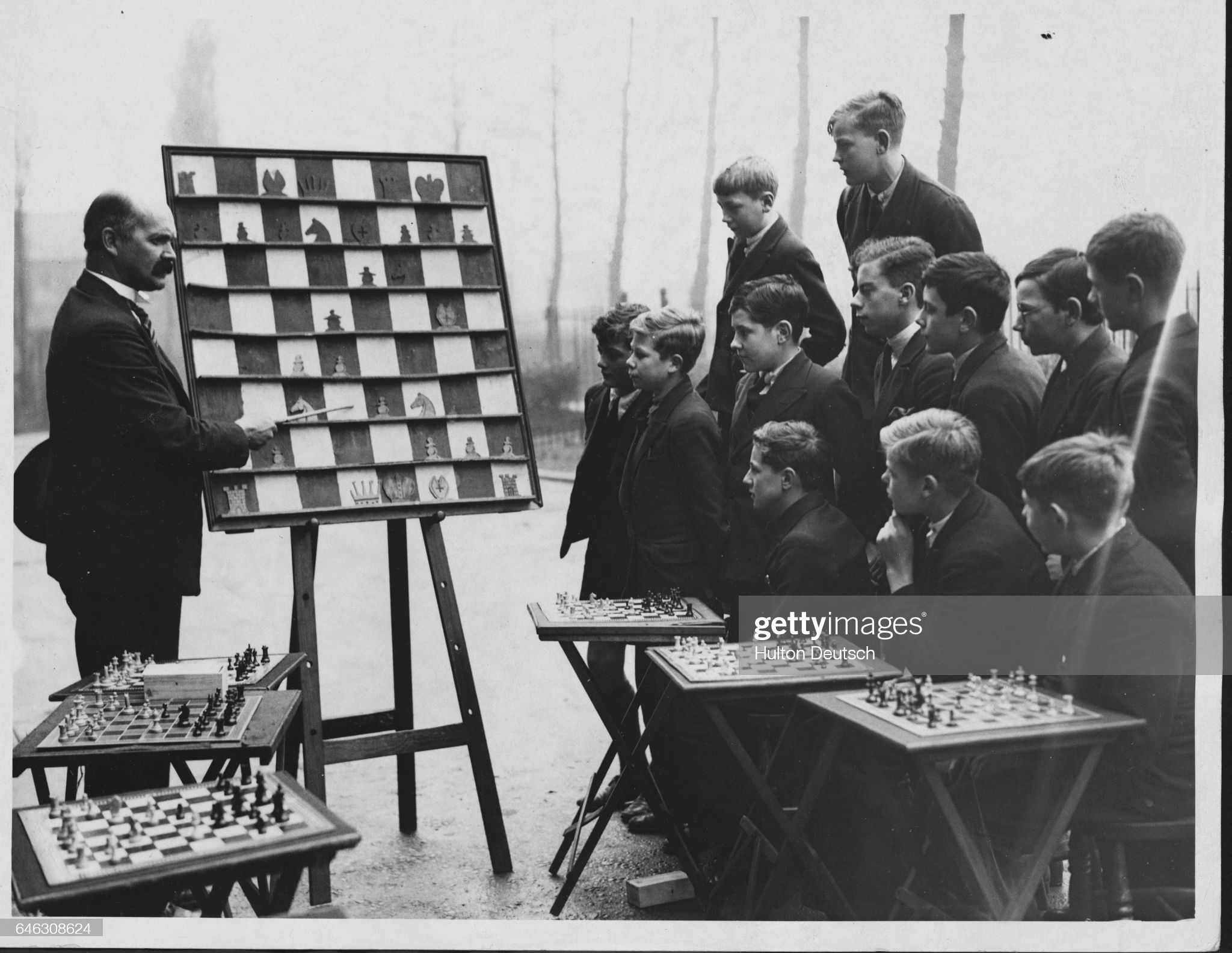

There he used his talent for juggling in 1920 to train a troupe of jugglers who gave a display at a school concert. This popular performance was repeated annually at Pocklington. Meanwhile be continued to compose chess problems and in 1923 published a book for beginners called The Chess Problem Hobby.”

In the 1939 register Cyril was recorded as residing at 67 Wood Green Road, Wednesbury, Staffordshire, England with Martha Partridge (born 29th June 1886) who was his Housekeeper.

His probate record appears in the England & Wales Government Probate Death Index 1858-2019 as :

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Robert Hale 1970 & 1976), Anne Sunnucks :

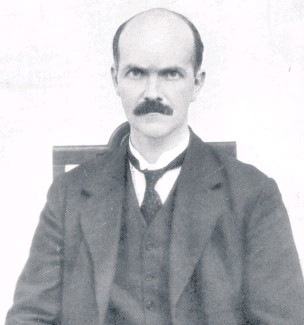

“International Master of the FIDE for Chess Compositions (1959) and International Judge of the FIDE for Chess Compositions (1957). Born on 10th October 1891. Died on 17th February 1964. Kipping was famous as a composer and an editor which he combined with is duties as Headmaster of Wednesbury High School from 1925 to 1956.

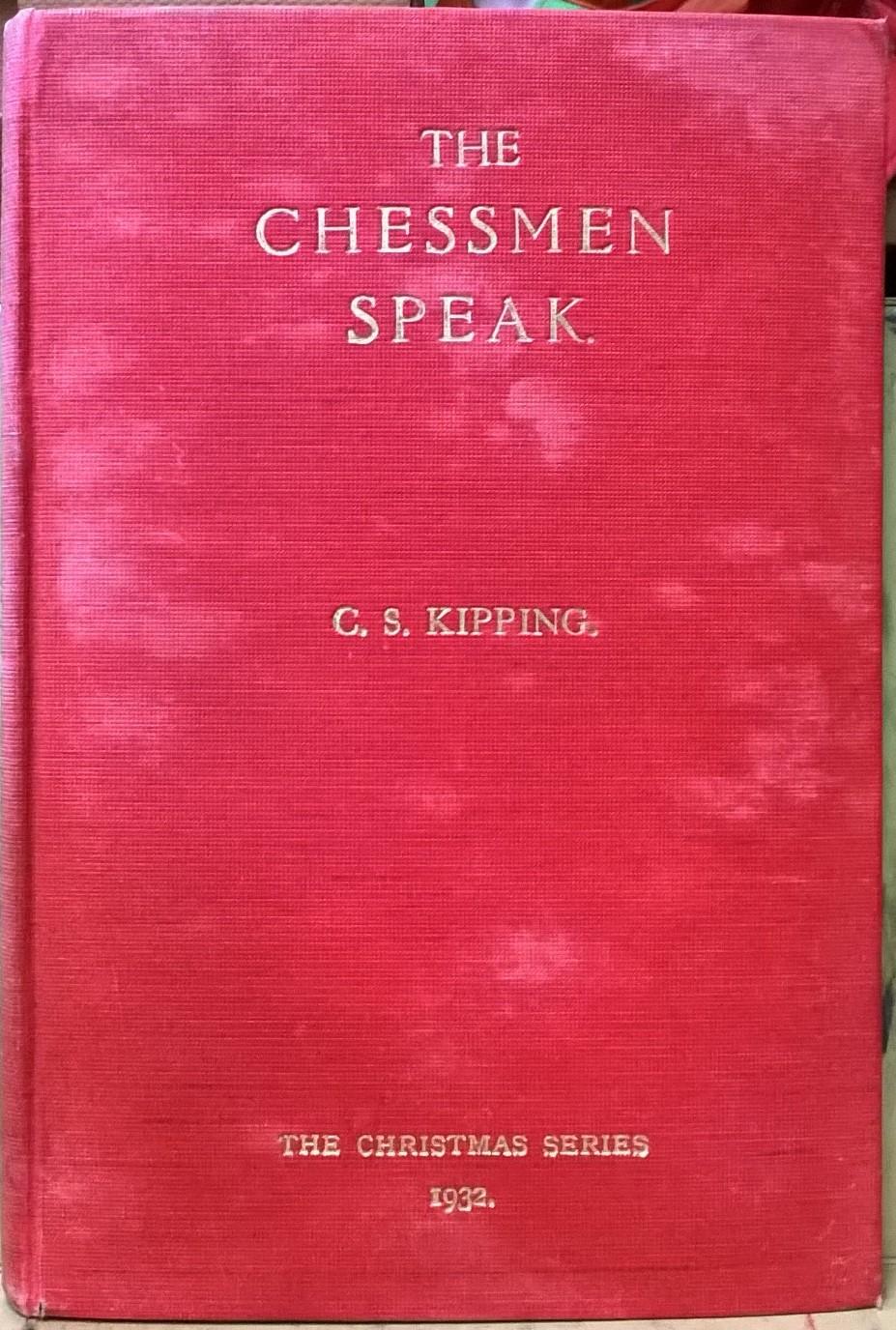

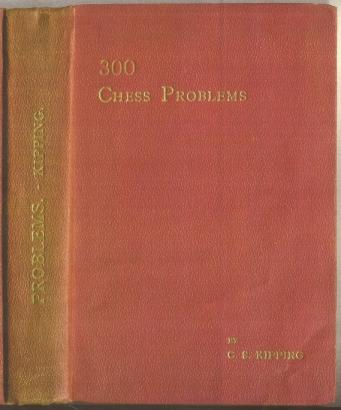

His editorial duties extended over more than forty years, and included the problem sections of Chess, Chess Amateur, and, for 32 years, the specialist magazine The Problemist from 1931. He was noted for his encouragement of beginners. His pamphlet ‘The Chess Problem Hobby‘ is an excellent beginner’s introduction. His other books included Chess Problem Science, The Chessmen Speak and 300 Chess Problems.

Kipping was one of the most prolific composers of all time, with over 7,000 problems to his credit. Many of his strategic three-movers have become classic. He was leading authority on halfpin two-movers. In his latter years, Kipping affectionately known as CSK – was Chairman of the International Problem Board which is now the FIDE Problem Commission.”

From British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXXIV (84, 1964), Number 4 (April), pp. 122-123 by John Rice:

“CS Kipping, one of the most famous of all British problemists, died during February at the age of seventy-two. As a composer, editor, writer and critic Kipping was without equal. It is impossible to do justice in only a few lines to his vast and unique contribution to chess problems: a few factual notes. most of them kindly supplied by RCO Matthews, must suffice.

Kipping was born in London on October 10th, 1891, After completing his studies, he took up teaching as a career, and in 1924 he was appointed the first headmaster of the newly-opened Wednesbury High School, which post he held until his retirement in 1956. He was a bachelor, and, especially during the later years of his life, his interests were centered mainly on the school and on chess problems.

Most readers will know of Kipping as the editor of The Problemist, the bi-monthly journal of the British Chess Problem Society. Before he took over The Problemist in 1931, he had been in charge of the problem section of the Chess Amateur, which he edited with great energy and enthusiasm. As well as The Problemist, he edited the problem pages of Chess from its first appearance. in 1936 until the section was suddenly discontinued without warning or explanation a few years ago. He also edited other columns at various times. He always took great care to help and encourage beginners, and it is probably true that every composer in this country below the age of about fifty came under his influence at one time or another.

As a young man, Kipping was a fierce avant-garde controversialist, championing the the cause of strategy in the three-mover in opposition to the then dominant model-mate school in this country. His attitude to the two-mover, as readers of The Problemist will know, was always a good deal more conservative; he would not tolerate at any price what he called ‘camouflage force,’ even in the modern problem. Yes, he appreciated the aims of the modern two-move composer much more than his writings on the subject suggest, being always ready to applaud excellence in any type of problem.

Kipping’s output numbered over 7,000 problems, probably a record. Many of his two-moves especially his ‘aspect’ tasks, were published under pseudonyms, of which the best was known was C.Stanley. He concerned himself little with artistic finish : once he had found a workable setting of a them he was engaged on, he would take little trouble over economy and presentation. Themes in which he interested himself include half-pin (in the two-mover), white King themes, interferences, and the grab theme (in the three-mover), and maximum tasks of all kinds, the subject of one of his books, Chess Problem Science. His other books include 300 Chess Problems (1916), and The Chessmen Speak (1932), in the AC White Christmas series.

In addition to all his other problem activities, Kipping was chairman of the International Problem Board, and curator of the half-pin section of the White-Hume Collection, which he took over on Hume’s death in 1936.

The majority of Kipping’s best problems were three-movers, three of the most famous of which are quoted here.”

Manchester City News, 1911

Mate in three

1 Ka5

First Prize

Dutch East Indies Chess Association Tourney, 1928

Mate in three

1 Ra3

First Prize

BCM, 1939 (II)

Mate in three

1 Be6

The first problem above was given in The Complete Chess Addict by Mike Fox and Richard James in the Desert Island Chess chapter. It is also given in a discussion of the Steinitz Gambit by ASM Dickins and H Ebert in 100 Classics of the Chessboard. Colin Russ on page 138 of Miniature Chess Problems from Many Countries gives the first problem as does John Rice on page 44 of Chess Wizardry : The New ABC of Chess Problems.

On a web site now only accessible vie the WayBack Machine there is a treasure trove of reminisces and memories of CHSK from himself, friends and pupils.

Anecdotes from former pupils.

A history from the Wolverhampton and District Chess League

Here is his Italian (only) Wikipedia entry.

Here is his entry on chesscomposers.blogspot.com