BCN remembers Gerald Abrahams who passed away in Liverpool on Saturday, March 15th 1980. He was buried in the Allerton Cemetery in the Jewish Springwood plot.

Gerald Abrahams was born in Liverpool on Monday, April 15th 1907. On this day the Triangle Fraternity was formed at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

His parents were Harry (b. 10th September 1880) and Leah (b. 12th March 1884) Abrahams (née Rabinowitz) who married in West Derby in the third quarter of 1903.

Gerald learnt chess at the age of ten during the first world war. He obtained an Open Scholarship to Wadham College, Oxford in 1925 reading PPE and earning himself an MA in Law in 1928. He became a practising barrister at Law.

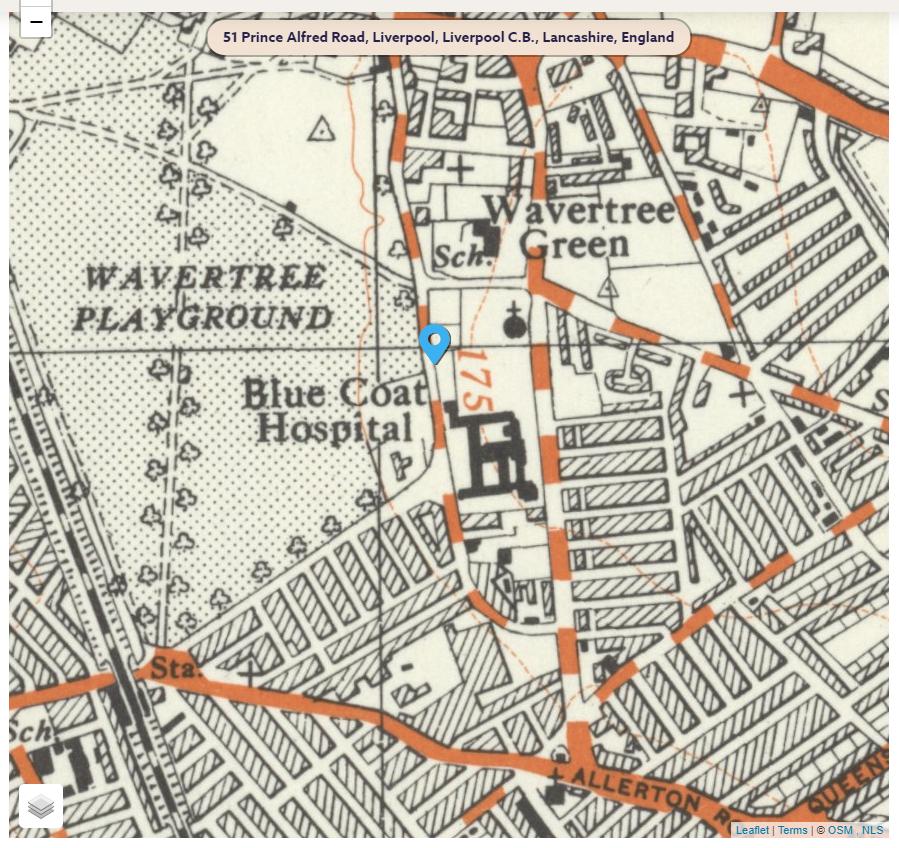

From the 1939 register we learnt that Harry was a Drapery manufacturer and Leah carried out “unpaid domestic duties”. Gerald was not an only child: the first born was Winnie (b. 22nd November 1903) who was a Secretary and Clerk Typist and factory assistant. Elsie Abrahams (b. 14th April 1905) helped her mother with “unpaid domestic duties”. Blanche was Gerald’s older brother and he was “General Assistant In Fathers Business Drapery Manufacturer”. Gerald is listed (aged 32) as a Barrister at Law and author. The family resided at 51 Prince Alfred Road, Liverpool, Lancashire (now L15 6TQ) and their original property has been since replaced.

We learn from “Philanthropy, Consensus, and broiges: managing a Jewish Community A history of the Southport Jewish Community

by John Cowell” of an incident in January 1942 that was to cause ripples in the community. The headline was

POLICE RAID DISTURBS CLUB CARD PLAYERS

The full list of people present seems to have been largely or entirely Jewish in religion or ethnicity: it included a famous chess-playing barrister from Liverpool, Gerald Abrahams, representing himself, who had taken a First in P.P.E. at Oxford, and later married Elsie Krengel, who had also been present, and with Leslie Black representing the rest of the defendants, apart from the hosts and Captain Lionel Husdan, who sent a letter to the court.

The full list of those present, charged with “resorting and playing in a common gaming house,” and bound over was as follows:- Mott Alexander, Fannie Finn, Maxwell Glassman, Kate Lippa, Myer Lister, Gertrude Mannheim, Joseph Mannheim, Rita Mannheim, Simon Mannheim, Harry Peters, Sadie Peters, Lily Leah Ross, Harry Sapiro, Benjamin Stone. Those charged with “resorting in a common gaming house” and bound over, were:- Gerald Abrahams, Joseph Appleton Bach, Samuel Myer Barnett, Herbert Solomon Isaacson, Elsie Krengel, Manuel Mannheim, Louis Michaelson, Abraham Ross, Bernard and Elsie Ross.

“Gerald Abrahams, the barrister charged, said he was interested to protect his reputation from being stigmatised by a conviction, and asked Sergeant Laycock about alcohol: the latter replied that none was being consumed. He submitted that the club was not a gaming house, and that draw poker had not been proved other than as a game of skill. Charges were dismissed against Henry, Eva and Marjorie Black, Myer Waldman, and Captain Lionel Husdan, of Ryde, Isle of Wight, all of whom had said that they were merely taking refreshments in the club, and had not played. David Platt said that he had not the slightest idea that they were breaking the law, and Mrs Platt said that it had not been a paying venture.”

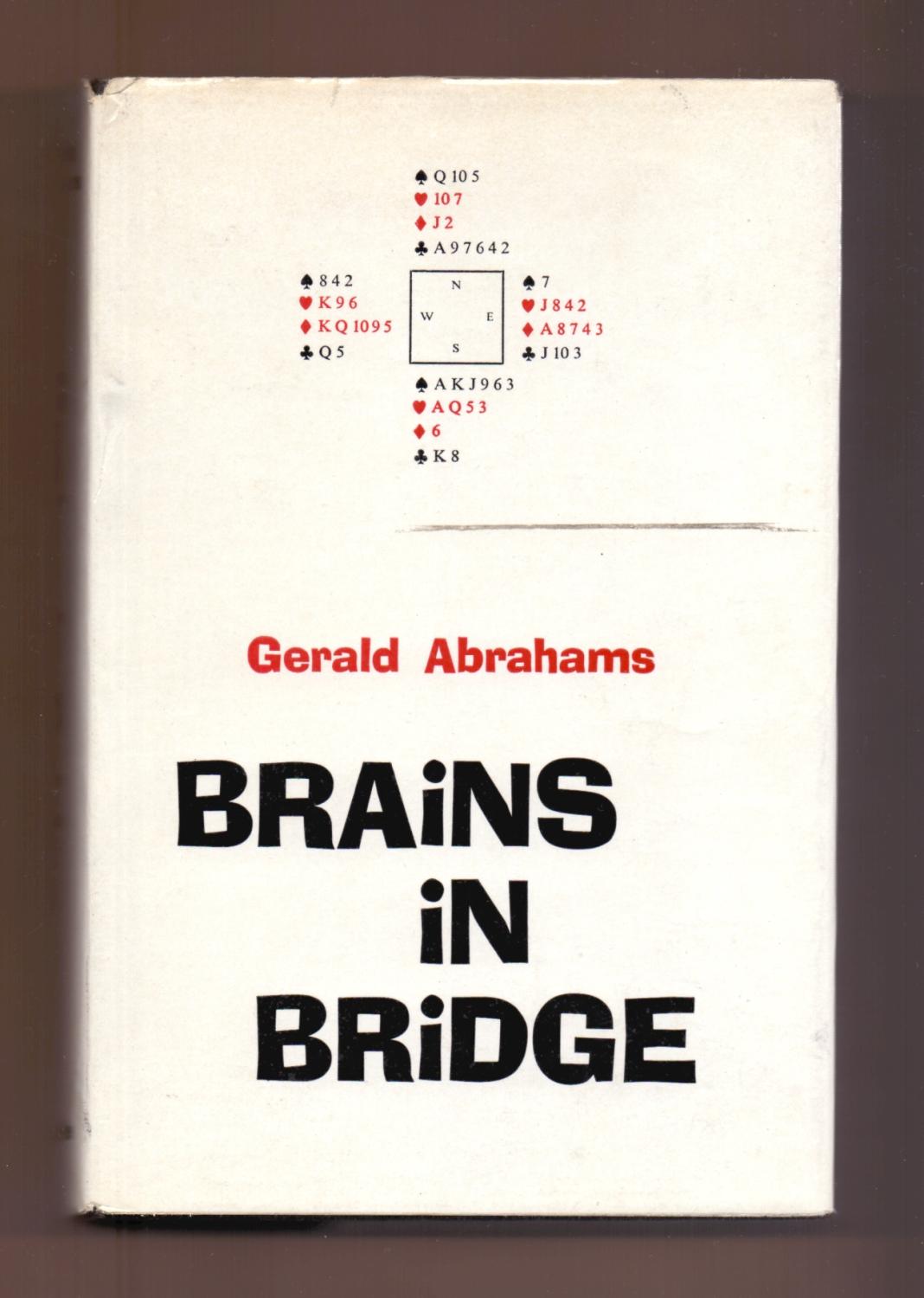

The Complete Chess Addict (Faber& Faber, 1987), Fox & James notes: that Gerald Abrahams as authority on bridge cast doubt on assertions that Emanuel Lasker “was good enough to represent Germany”

Gerald’s comparisons of chess and bridge are discussed by Edward Winter in Chess Facts and Fables (McFarland, 2005) page 130 in GAs 1962 book Brains in Bridge:

Gerald eventually married Elsie Krengel (born 15th January 1909) in the fourth quarter of 1971 in Liverpool at the age of 64. Elsie had lived in the Southport area for most of her life and her family was associated with the manufacture of handbags. They had known each other for many years (at least since 1942 as mentioned previously).

Leonard Barden modestly recounts :

“At the end of Nottingham 1954 Gerald claimed that Alan Phillips had accepted his draw offer so tieing Gerald for the British championship with some rabbit whose name escapes me. When Phillips strongly denied having accepted the draw, Gerald collapsed on the floor and had to be aided by his old enemy Dr. Fazekas.”

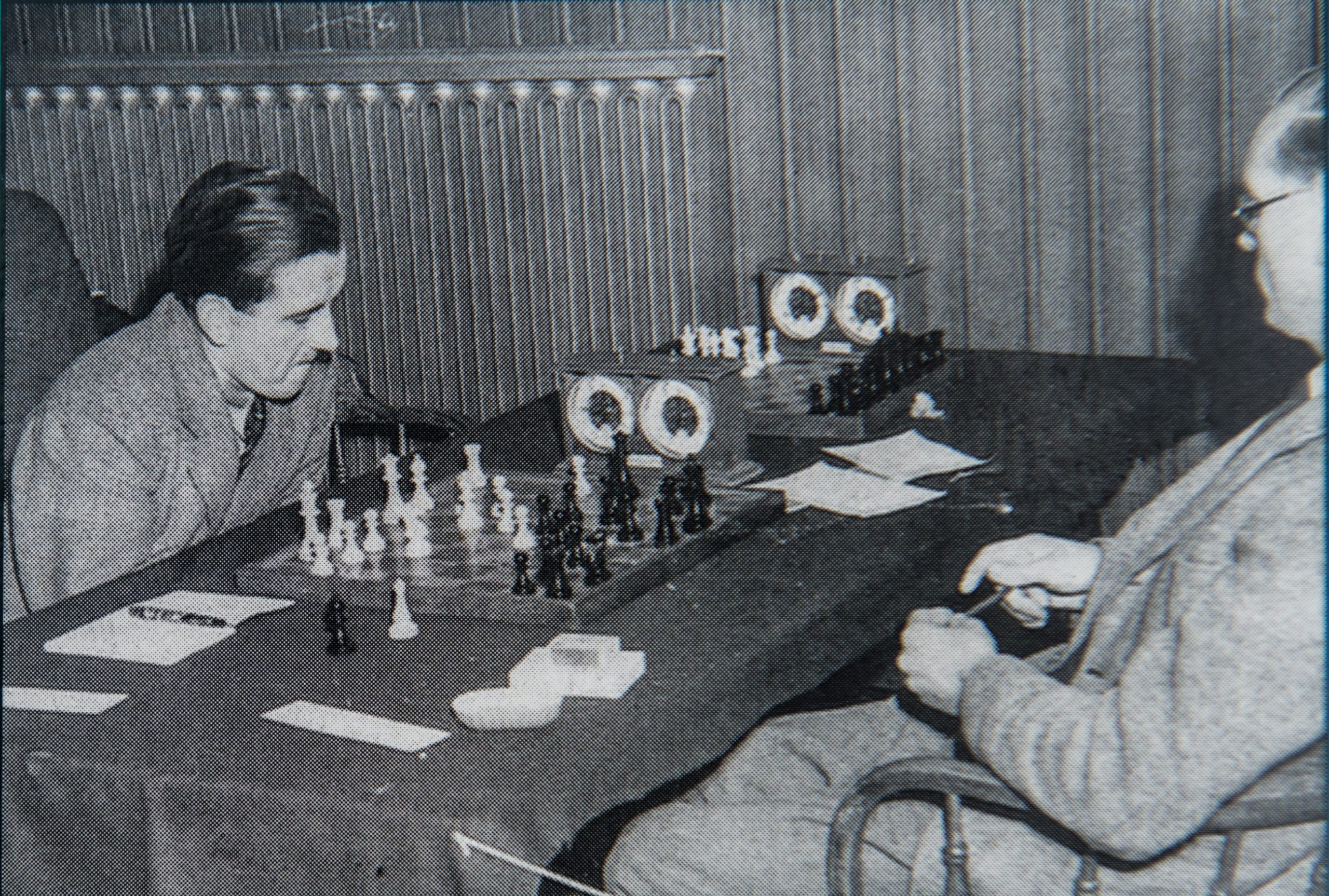

From The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match (1946) by Klein and Winter:

“G. Abrahams was born in Liverpool in 1907. He learned chess at the age of ten, and showed an early aptitude for tactical complications. He has played with varying success, his best performances being third and fourth with Rossolimo, behind Klein and Najdorf, but head of List at Margate, 1938, and fourth, fifth and sixth with Sir George A. Thomas and König in London, 1946. He has made two valiant bids for the British Championship.

A graduate of Oxford, he is a barrister by profession and has written several books, including some fiction. He has solidified his chess without allowing it to become dry. Indeed, most of his games sparkle with interesting complications.”

Harry Golombek OBE wrote (in The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977)):

“Brilliant British amateur who in the 1930s was playing master-chess. In that period he was the most dangerous attacking player in England.

He was in the prize-list (i.e. in the first four) in the British championship on three occasions 1933, 1946 and 1954. His best international performance was in the Major Open at Nottingham in 1936 where he came =3rd with Opocensky. Another fine result was his score of 1.5-0.5 against the Soviet Grandmaster Ragozin, in the 1946 Anglo-Soviet radio match.

He is the inventor of the Abrahams variation in the Semi-Slav Defence to the Queen’s Gambit: 1.P-Q4, P-Q4;2.P-QB4, P-QB3;3.N-QB3, P-K3;4.N-B3, PXP;5.P-QR4, B-N4;6.P-K3,P-QN4;7.B-Q2, P-QR4; 8.PxP, BxN;9.BxB,PxP;10.P-QN3,B-N2;

This is sometimes known as the Noteboom variation after the Dutch master who played it in the 1930s, but Abrahams was playing it in 1925 long before Noteboom.

He is a witty and prolific writer on many subjects: on law (he is a barrister by profession), philosophy, and chess; he also writes fiction. His main chess works are: The Chess Mind, London 1951 and 1960

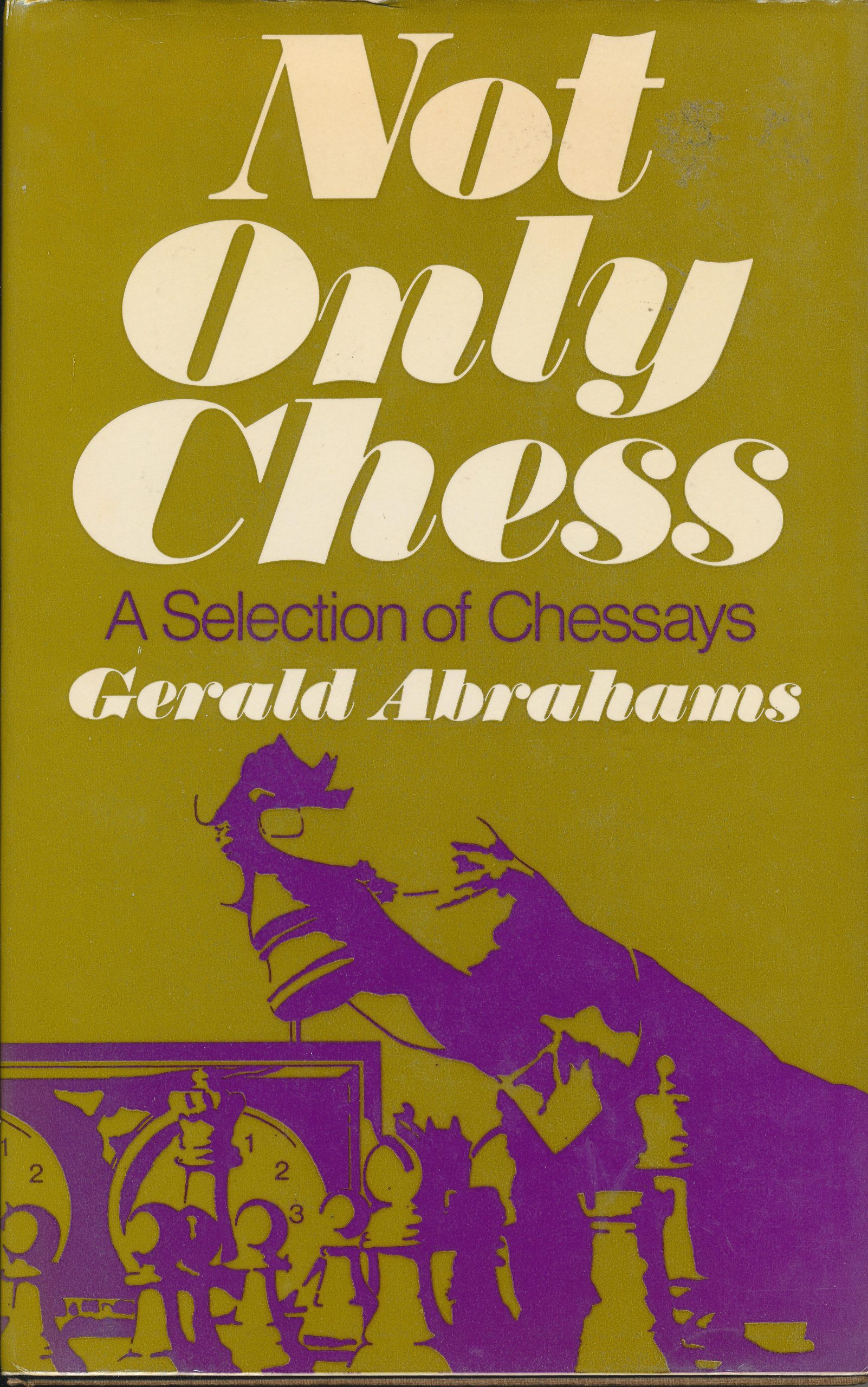

and here is a later cover:

and Not Only Chess, London 1974.

Edward Winter in Kings, Commoners and Knaves, cites the subtitle of the above book in his page 235 list of chessy words: “A selection of Chessays”.

From Not Only Chess we learn that GAs favourite game was played in 1930 against Edmund Spencer of Liverpool. “Edmund Spencer was a man who is remembered with affection by all players who ever met him, and who is remarkable in that his strength developed in what should have been hid middle life. When he died, lamentably early, in the 1930s, at about 53 he was at his best, and of recognised master status.

This game was played in 1930.”

and for an alternative view of the same game:

GA is amongst a rare breed of game annotators claiming the title of An Immortal for one of his own games. Edward Winter devotes a couple of column inches discussing exactly which year the game was played between 1929 and 1936. Here is the game:

For more of GAs excellent games see the superb article further on by Steve Cunliffe. Also, Not Only Chess in Chapter 28 (“A Score of my Scores”) contains a veritable feast of entertaining games of GAs).

Gerald famously fell out with Anne Sunnucks when he discovered she had omitted him from her 1970 Encyclopaedia of Chess. Despite this the 1976 edition was also devoid of a mention.

From The Oxford Companion to Chess (OUP, 1984 & 1996), Hooper & Whyld:

“The English player Gerald Abrahams (1907-80) introduced the move when playing against Dr. Holmes in the Lancastrian County Championship in 1925 (ed: January 31st in fact) . Abrahams played the variation against his countryman William Winter (1898-1955) in 1929 and in the same year Winter played it against Noteboom, after whom it is sometimes named. (Dr, Holmes was the favourite pupil of Amos Burn and a leading ophthalmologist).

The precursor, known from a 16th-century manuscript, was published by Salvio in 1604:

1.d4 d5;2.c4 dxc4;3.e4 b5;4.a4 c6;5.axb5 cxb5;6.b3 b4;7.bxc4 a5; 8.Bf4 Nd7;9.Nf3

Writing in 1617, Carrera made his only criticism of Salvio’s analysis in this variation. He suggested 8…Bd7 instead of 8…Nd7, or 9.Qa4 instead of 9.Nf3. Salvio nursed his injured pride for seventeen years and then devoted a chapter of his book to a bitter attack on Carrera. The argument was pointless: all these variations give White a won game.”

GA famously wrote :

Chess is a good mistress, but a bad master

and also

The tactician knows what to do when there is something to do; whereas the strategian knows what to do when there is nothing to do.

and

In chess there is a world of intellectual values

and

Good positions don’t win games, good moves do

and

Why some persons are good at chess, and others bad at it, is more mysterious than anything on chess board.

In the recently (February 25th, 2020) published “Attacking with g2 – g4” by GM Dmitry Kryakvin writes about Abrahams as follows :

“It is believed that the extravagant 5.g2-g4 was first applied at a high level, namely in the British Championship by Gerald Abrahams. Abrahams was a truly versatile person – a composer, lawyer, historian, philosopher, politician (for 40 years a member of the Liberal Party) and the author of several books. Of his legal work, the most famous is the investigation into the murder of Julia Wallace in 1931 in Liverpool, where her husband was the main suspect. As an alibi, William Herbert Wallace claimed he was at a chess club. Dozens of books and films have been devote to the murder of Mrs. Wallace – indeed, this is a script worthy of Arthur Conan Doyle or Agatha Christie!

Abrahams played various card games with great pleasure and success, but the main passion of the Liverpool resident was chess. Abrahams achieved his greatest success in the championships of Great Britain in 1933 and 1946, when he won bronze medals. The peak of his career was undoubtedly his participation in the USSR-Great Britain radio match (1946) where on the 10th board Abrahams beat Botvinnik’s second and assistant grandmaster Viacheslav Ragozin with a score of 1.5-0.5

Gerald Abrahams had a taste of studying opening theory, and made a distinct contribution to the development of the Noteboom Variation, which is often known as the Abrahams-Noteboom.

Ten years after he introduced the move 5.g2-g4 to the English public (1953), the famous grandmaster Lajos Portisch brought it into the international arena.”

Gerald was also a keen studies composer. Here are some examples of his work:

Gerald Abrahams, 1923

1/2-1/2

Solution: 1. Ra3! Ra3 […a1=q;2.Ra1 Ba1;3.d7 Kf7;4.d8=q];2.e8=q a1=q;3.Qd7

and

Gerald Abrahams, 1924

1-0

Here is an interesting article by Tim Harding on the naming of the Abrahams-Noteboom Variation of the Semi-Slav Defence

Here is an article about GA and a blindfold exhibition

Gerald Abrahams contributed to opening theory in the Queen’s Gambit Declined / Semi-Slav Defence with his creation of the Abrahams-Noteboom Defence as discussed in the following video :

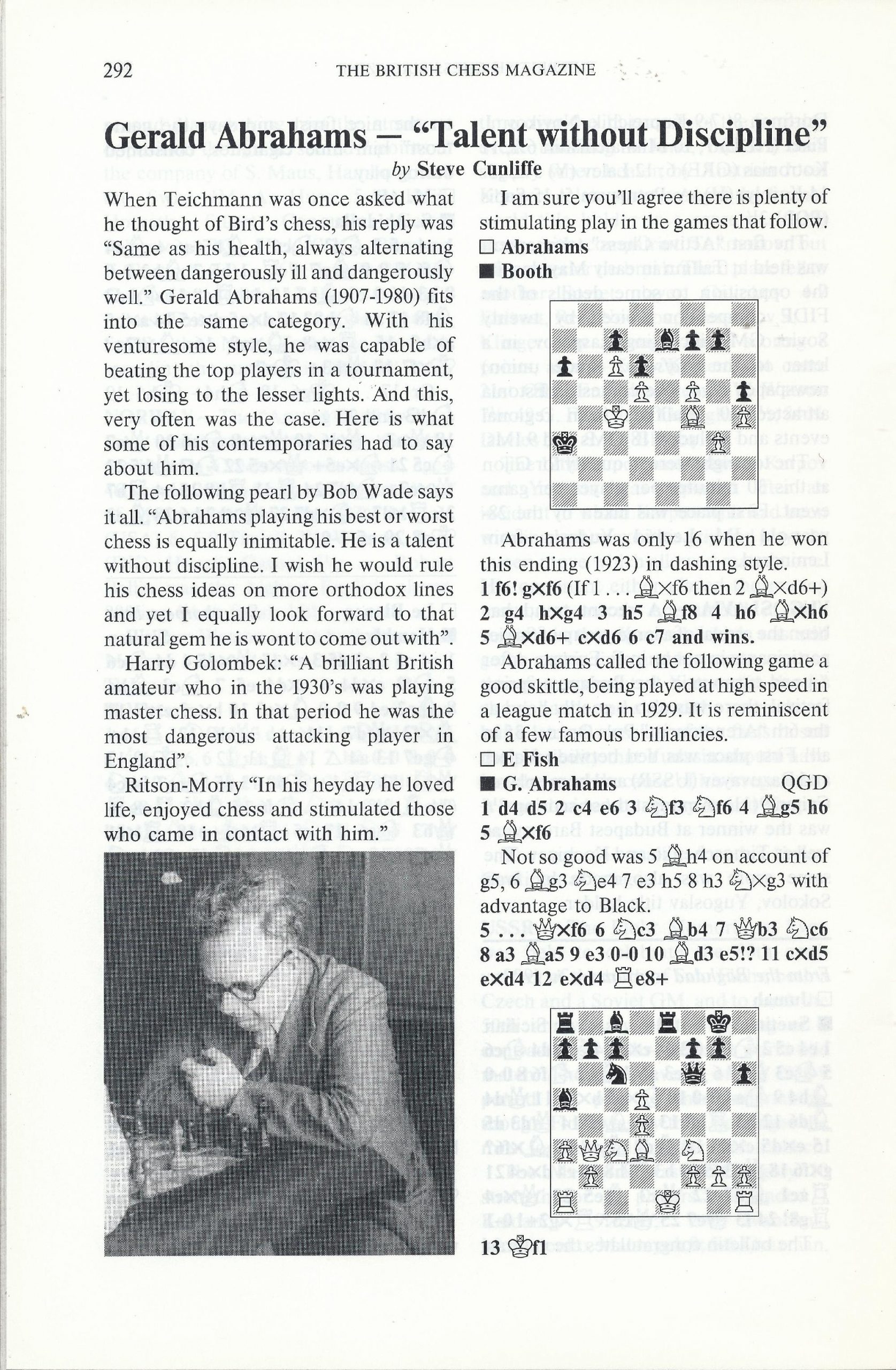

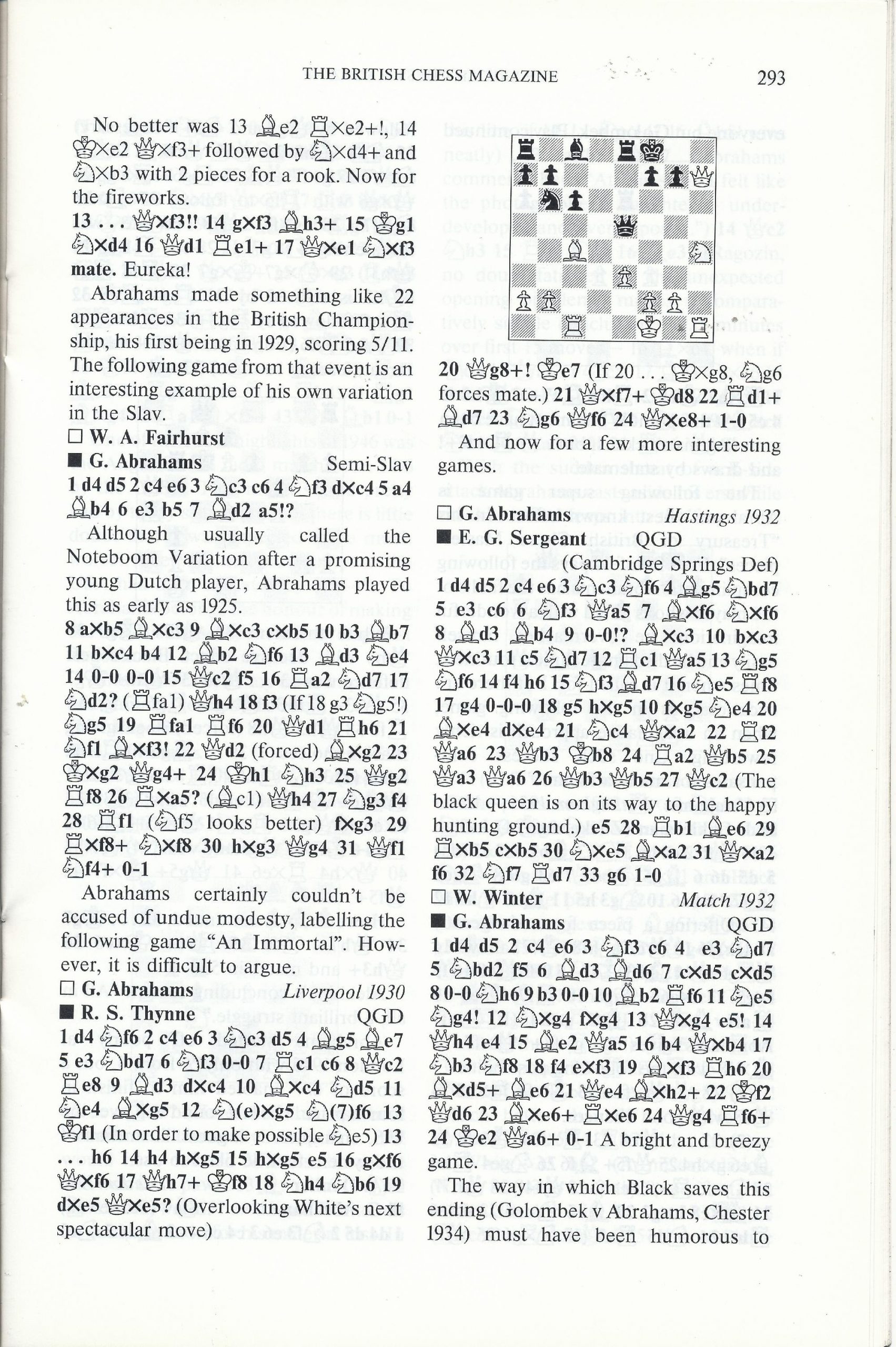

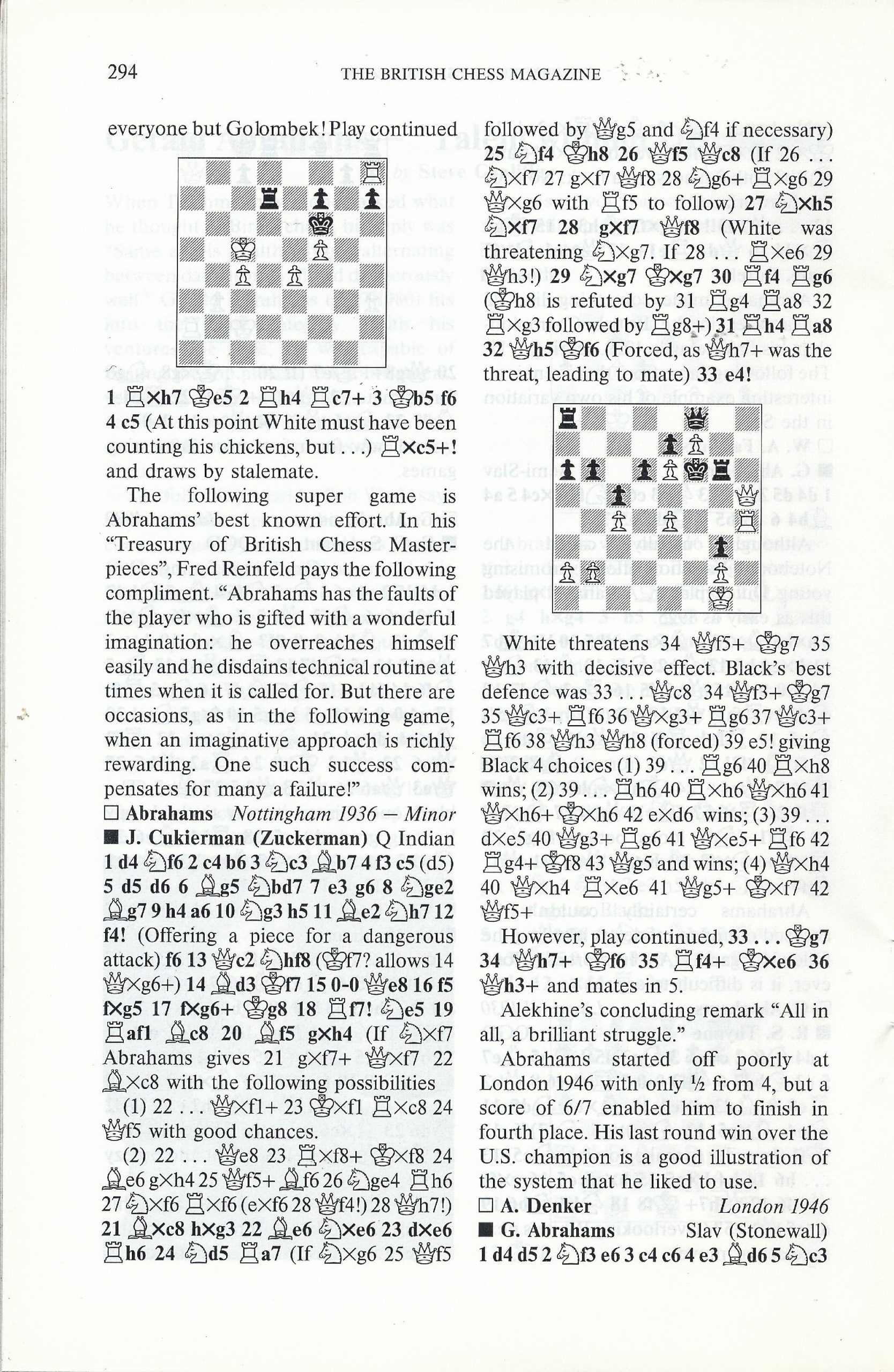

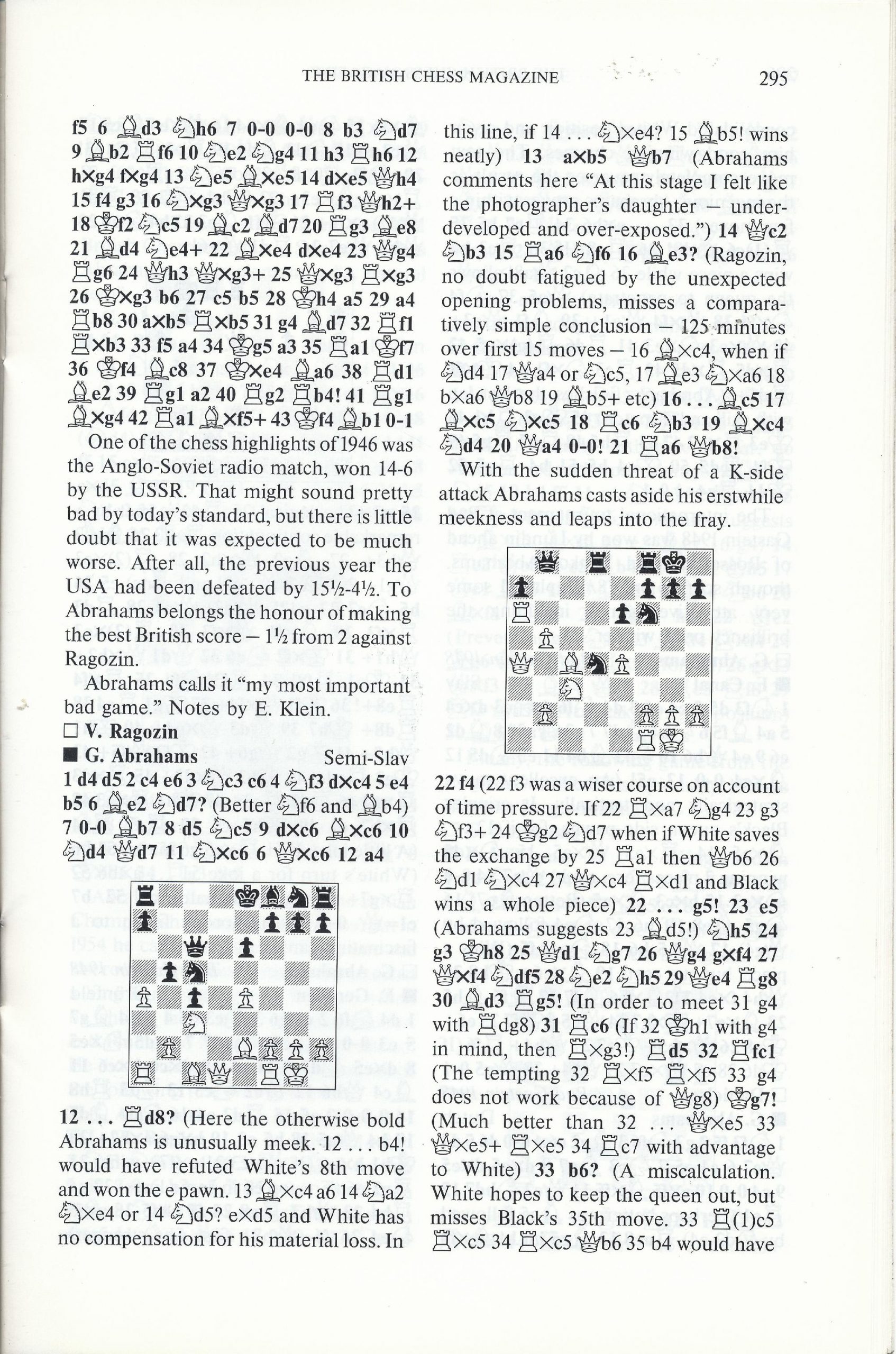

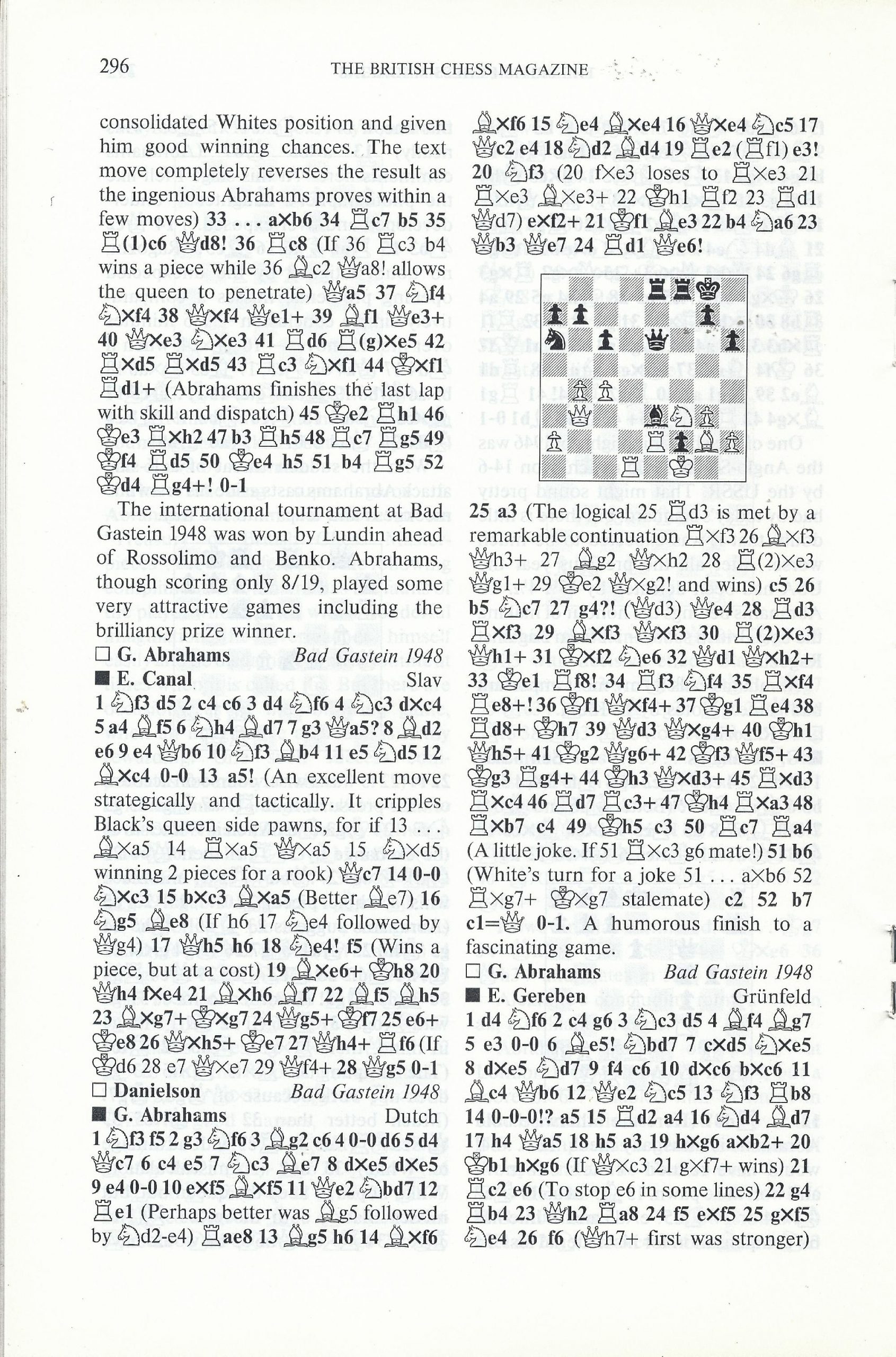

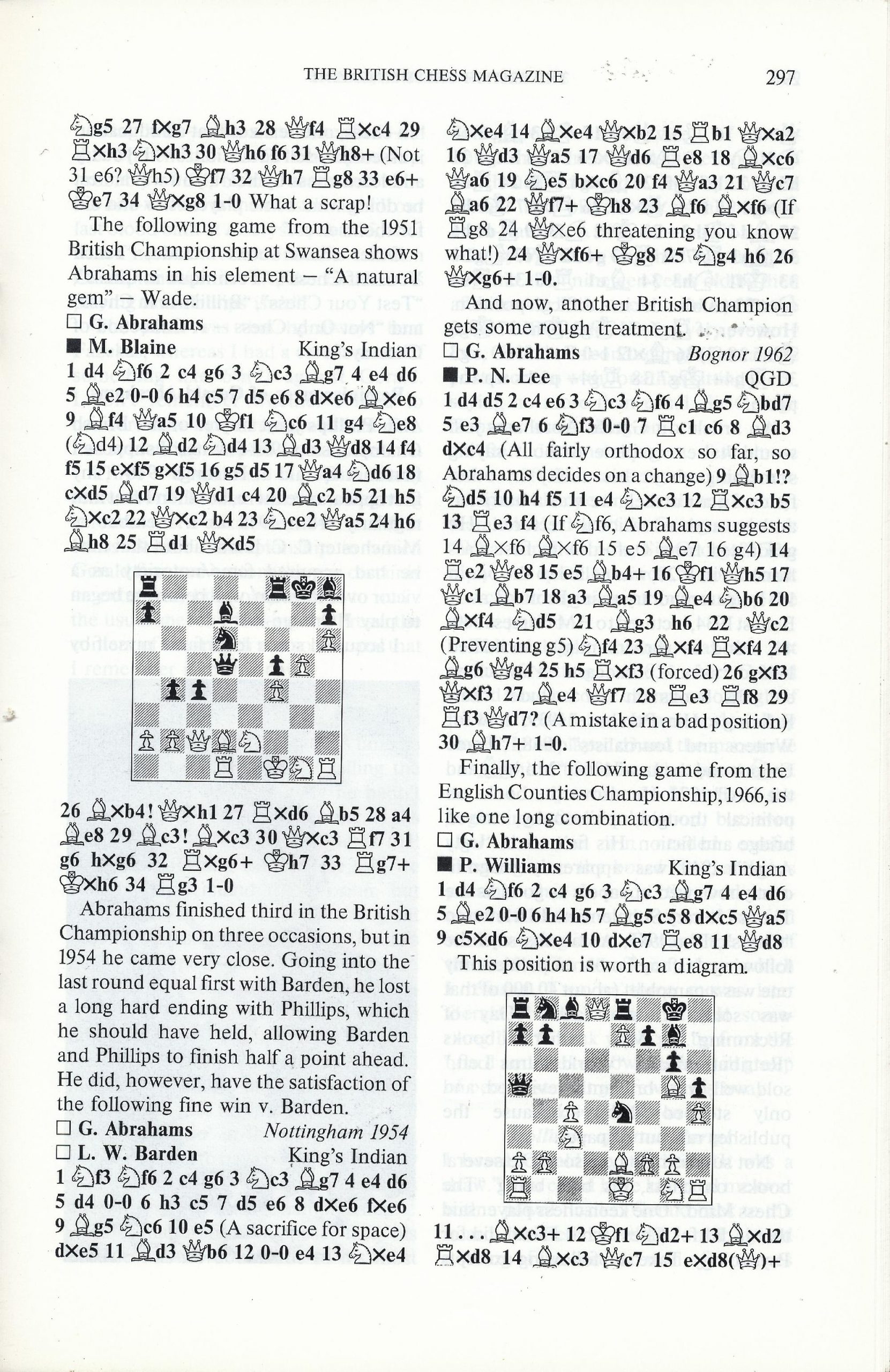

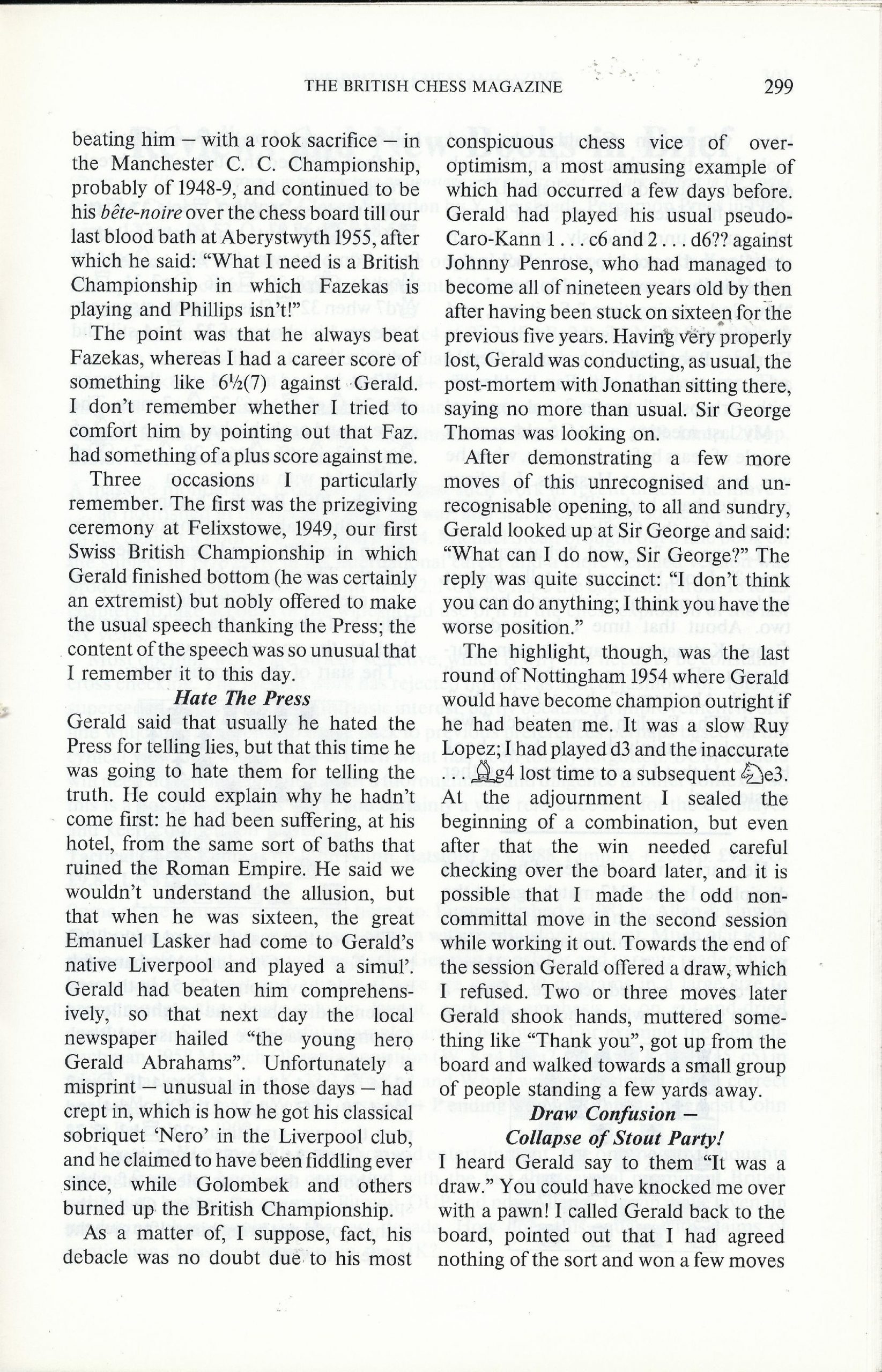

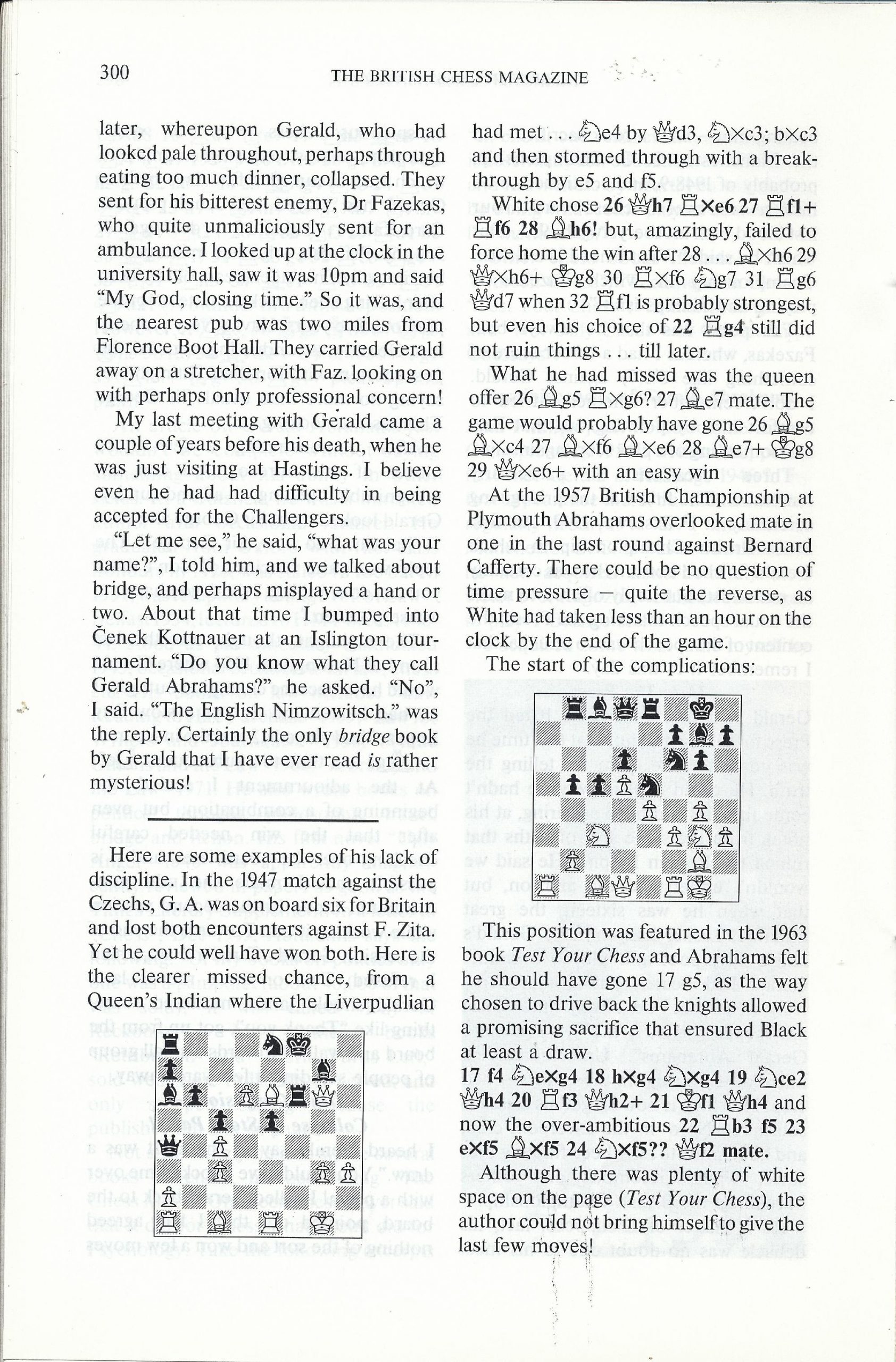

Here is a nine page article (Gerald Abrahams – Talent without Discipline) written by Steve Cunliffe that appeared in British Chess Magazine, Volume CVIII (1988), Number 7 (July), pp. 292-300:

Here is his Wikipedia entry

See his games at Chessgames.com