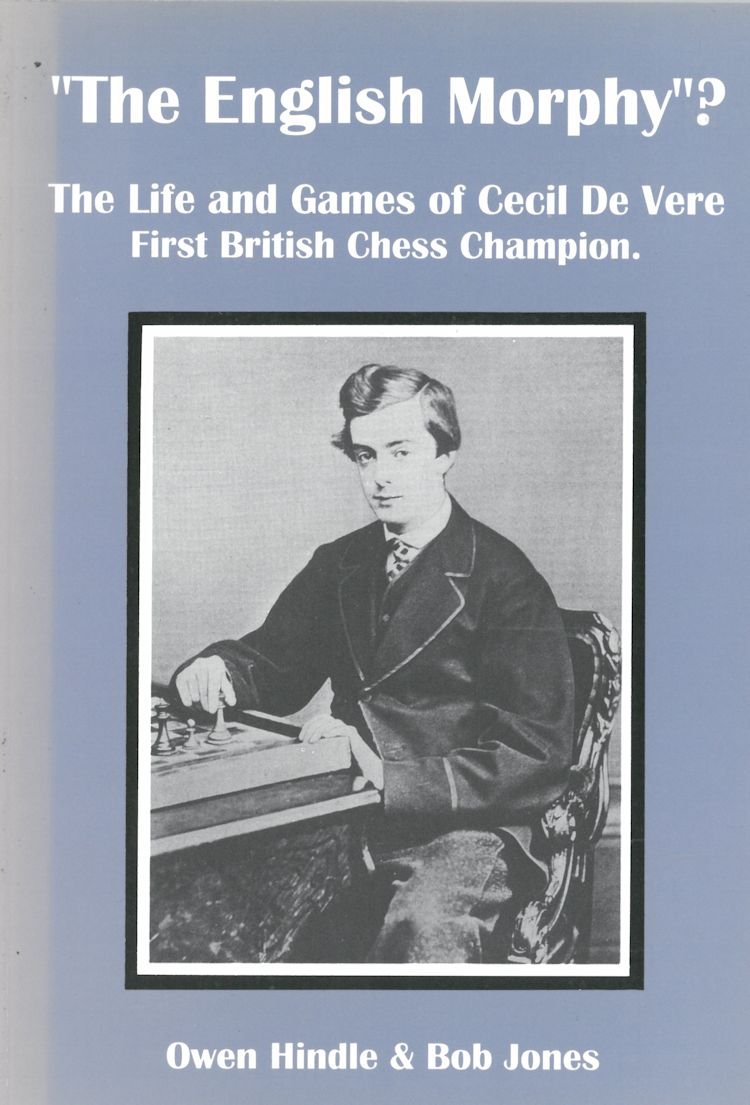

We remember Cecil Valentine De Vere (14-ii-1846 09-ii-1875)

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

Cecil Valentine De Vere, pseudonym of Valentine Brown, winner of the first official British Championship tournament organized by the British Chess Association in 1866. He learned the game in London before 1858 and practised with Boden and the Irish player Francis Burden (1830-82). De Vere played with unusual ease and rapidity, never bothering to study the books. His features were handsome (an Adonis says MacDonnell), his manner pleasant, his conduct polite. He “handled the pieces gracefully, never “hovered” over them, nor fiercely stamped them down upon the board … nor exulted when he gained a victory…in short, he was a highly chivalrous player.’ So wrote Steinitz who conceded odds in a match against De Vere and was soundly beaten, (See pawn and move.) De Vere’s charm brought him many friends.

At about the time that he won the national championship his mother died, a loss he felt deeply, “The only person who ever cared for me”.

Receiving a small legacy he gave up his job. which Burden had obtained for him at Lloyds the underwriters, and never took another. He entered some strong tournaments but always trailed just behind the greatest half-dozen players of his time. His exceptional talent was accompanied by idleness and lack of enthusiasm for a hard task. On the occasion of the Dundee tournament of 1867 he took long walks in the Scottish countryside with G. A. MacDonnell, who writes that a ‘black cloud’ descended on De Vere. It may have been the discovery that he had tuberculosis; more probably he revealed to the older man a deep-rooted despair, the cause perhaps of his later addiction to alcohol.

In 1872 Boden handed over the chess column of The Field to provide him with a small income; but in 1873 the column was given to Steinitz on account of De Vere’s indolence and drunkenness. At the end of Nov, 1874 his illness took a turn for the worse, he could hardly walk and ate little. His friends paid to send him to Torquay for the sea air, and there he died ten weeks later. He had failed to nourish a natural genius in respect of which, according to Steinitz, De Vere was “second to no man, living or dead*.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks :

First official British Chess Champion, Cecil de Vere was born on 14th February 1845 (in Montrose, Angus, Scotland : Ed.) and was taught to play chess when he was 12 by a strong London player, Francis Burden. By the time he was 15, he was a regular visitor to “The Divan” on a Saturday afternoon.

At the age of 19 De Vere played a number of games against MacDonnell winning the majority of them. So great was his promise that the City of London Chess Club raised a purse for a match between him an Steinitz, Steinitz giving the odds of a Pawn and a move. De Vere won.

In 1866 the first British Championship, organised by the British Chess Association was held. De Vere won, ahead of MacDonnell and Bird, and so became the first British Champion at the age of 21.

The following year in the Paris 1867 tournament, he was 5th out of a field of 13, and he tied for 3rd prize in the Dundee Congress, ahead of Blackburne, having beaten Steinitz in their individual game.

While he was in Dundee, De Vere learned that he was suffering from Tuberculosis. The news changed his whole life. Having recently inherited a few hundred pounds, he gave up his job at Lloyd’s and started living on his capital, determined to enjoy the few years he had left. He continued to play chess, but his performances were marred by his newly acquired addiction to the bottle.

De Vere was once described as “A Morphy without book knowledge”. His talent was great enough for him to be able to take on the leading masters of the day without any study or preparation, but more than that is needed to reach the top. De Vere lacked the strength of character and health to fulfill his early promise. He died a few days before his thirtieth birthday.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek :

The first official British Champion and a player of great promise who might well have attained world fame had he not be carried off by that nineteenth-century British scourge, tuberculosis, before he attained the age of thirty.

Most of the details of his life are to be found in the writings of G.A. MacDonnell, who met him when De Vere was fourteen and was so struck by his good looks as to refer to him as “Adonis”.

His first tournament success came in 1866 at the London Congress organised at the St. George’s Club in the first few days and then in other venues by the British Chess Association. De Vere played in two events, a Handicap tournament and a Challenge Cup event which was in fact the first British Championship tournament.

The Handicap tournament was run on the same lines as London 1851, i.e. it was a knock-out event with matches of three games, draws not counting. De Vere met Steinitz in round 1 and lost by 2-1.

The first British championship tournament was an all-play-all event in which the ties were decided by the first player to win three games and in which the championship went to the winner of the biggest number of games. De Vere was an easy winner with 12 wins, followed by MacDonnell and J.I. Minchin 6, H.E Bird 3 and Sir John Trelawney 0.

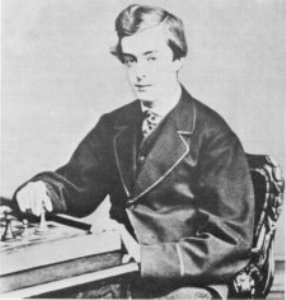

Thus De Vere was the first British Champion and at that age of twenty-one. A photograph of him about this time shows that he bore a remarkable likeness to the international master John Nunn, who won the European Junior championship a hundred years after De Vere’s death.

De Vere confirmed his position as a leading British player by coming first in another tournament in 1866 at Redcar in North Yorkshire. This was an event open to all British amateurs and among his opponents were Owen, Thorold and Wisker.

It was in the following year that he commenced his career in international chess. In the important double-round tournament at Paris he occupied an honourable fifth place out of 13 players. At Dundee (the third congress of the British Chess Association) he finished equal 3rd with MacDonnell, below Steinitz but beating him in their individual game and coming ahead of Blackburne.

It was during his visit to Scotland (he went to stay with relatives after the tournament) that he learnt he was afflicted with consumption. This knowledge, together with the death of his mother, drove him to drink which was to accelerate his end.

inheriting a few hundred pounds, presumably from his mother, he gave up his post at Lloyd’s and decided to live on his capital together with such additional sums as he could earn from chess.

In this respect his addiction to drink proved a handicap. For example, he held the post of chess editor of The Field in 1872 but lost it after some eighteen months through inattention to work.

Meanwhile he continued to show his great talent for the game. Defending the title of British Champion in a very strong field at the next British Chess Association congress (1868/9) he cam equal first with Blackburne but lost the play-off at the London Club in March 1869.

In 1870 at the very strong Baden-Baden double-round tournament, he came equal sixth with Winawer but was much outdistanced by Blackburne who came third with 3.5 more pints than De Vere. But already his illness was taking a strong hold on him. At his next and last appearance in a tournament of note. London 1872, he tied with Zukertort and MacDonnell =3rd out of 8 players. In the play-off for third and fourth prizes he lost to MacDonnell and scratched to Zukertort, Later in the year he did tie for first place with Wisker in a weaker British championship tournament and, with De Vere now clearly ill, Wisker had an easy victory in the play-off.

At his last appearance at a chess event, a match at the City of London Club between that Club and Bermondsey, he looked a dying man. A subscription was made to send him to Torquay but it was too late and he died within five days of his thirtieth birthday.

Here are some of his games at chessgames.com

The English Chess Forum contains a brief discussion initiated by John Townsend (Wokingham) of manuscripts attributed to CdV.

Here is his Wikipedia entry