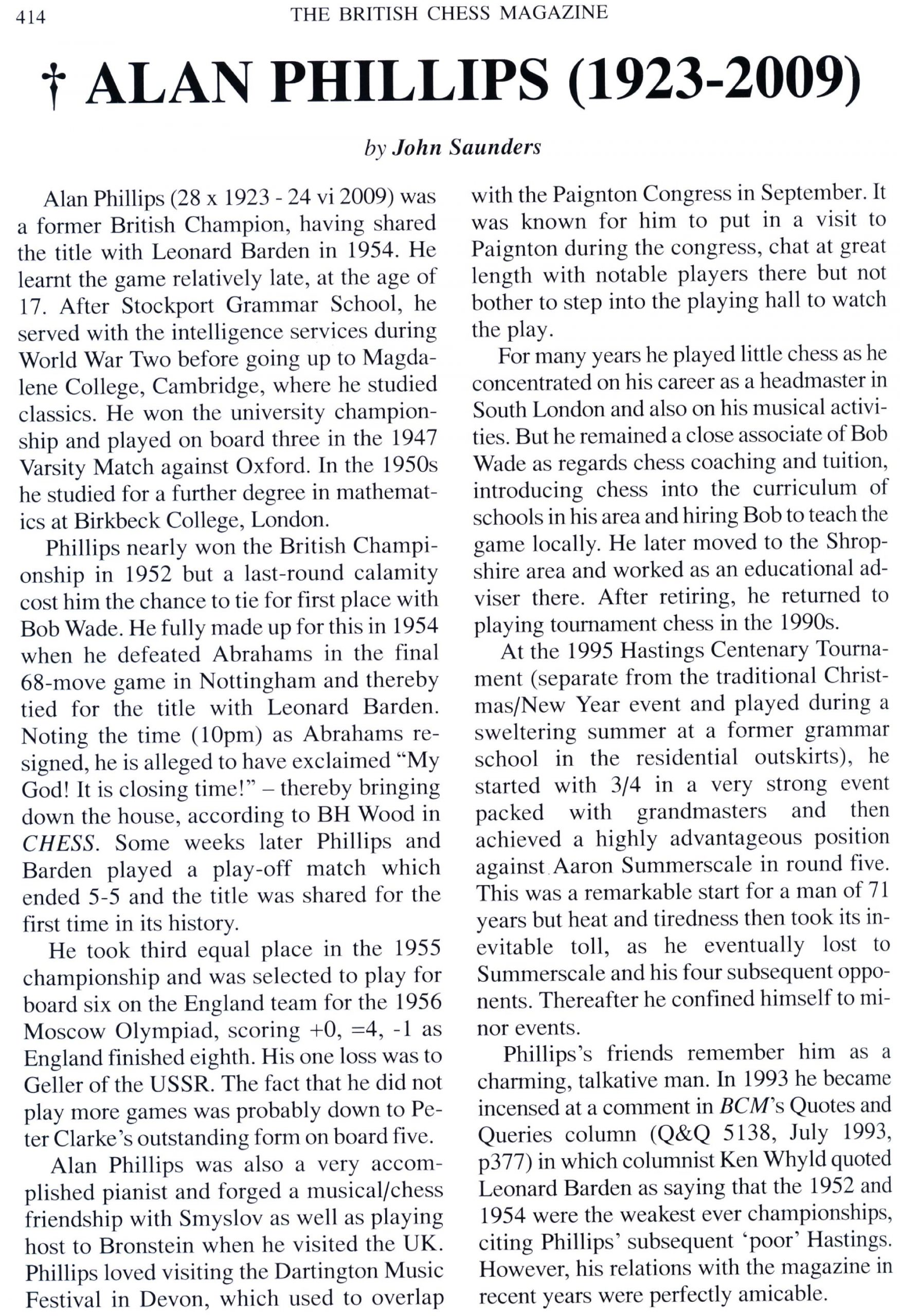

BCN remembers Alan Phillips (28-x-1923 24-vi-2009)

Here is his far too brief Wikipedia entry

From Chessgames.com :

“Alan Phillips, joint British Champion in 1954, was born in England in 1923. He was the author of Chess: 60 Years on with Caissa and Friends (Caissa Editions, 2003) and The Chess Teacher (Cadogan, 1995).”

Here is an item from the Shropshire Chess web site

Here is Alan Phillips autobiography from his own book, Chess: Sixty years on with Caissa & Friends

“Born in Stockport in 1923,I was playing pontoon in an air-raid shelter in the autumn of 1940 with a friend from our school, Stockport Grammar, when he suddenly announced that he knew a better game, being the school chess champion. Ostensibly studying for a Cambridge Scholarship with a view to reading Classics, I played about 200 games with Norman Stephens, emerging the victor perhaps because I studied Alekhine’s and Euwe’s games, obtained from the Public Library, whence I had been borrowing difficult piano works for the previous two years. When I got up to Magdalene in 1941, I found standing next to me in the University Chess Club Wykehamist James Lighthill, destined to become, arguably, our greatest applied mathematician of the second half of the last century; I played chess with him one evening a week and piano duets another, and as Match Captain and Hon.Sec. in my second year – shared top board, while now supposedly reading Italian, as a War Office scheme, and French, languages I unfortunately then considered beneath contempt, compared with the glory that was Greek.

Enrolled but not commissioned – the War Office having ratted on its promise to a large bunch of first-class linguists – in the Army Intelligence Corps from August 1943 to October 1946,I spent nearly three years abroad in Sicily and Palestine, riding a motor-bike – our American equivalents in the CIC were mostly majors or colonels and rode in Cadillacs – and playing, when stationary, much music with singers and violinists, especially in Palestine, and chess with the Captain of the Harbour in Sicily, a charming moustached Neapolitan who got about three draws in 300 games, and then in Haifa, Hadera and Jerusalem chess clubs, beating the youth champion of Palestine and Aloni when he played simultaneously, but losing to Porath, and enjoying ‘skittles’ in cafes with many other players of near-master rank. Demobilised and put, like the Goons, on the Z-reserve in autumn 1946, I went back to Cambridge to read Classics Pt II and found Peter Swinnerton-Dyer, as far as I know our best number theorist of the past fifty years, waiting for me – we tied for the University Championship having begun a series of trips to Hastings with Alan Truscott, and later continued to Birmingham for the Midland Championship, which I won in 1951.

I usually won prizes in increasingly strong sections at Hastings except in two Premiers, 1950-1 and 1954-5, when my emotions were otherwise engaged, as happened in the British Championship in 1952, when, after I had beaten all the best players and scored 7/8 with three rounds to go, a girl-friend turned up and I lost my last three games, refusing a draw in round nine in a not superior position, not out of arrogance, but in order to clinch the title.

Otherwise, with one or two exceptions, I only lost to the strongest players in the British Championships I played in, i.e. 1949-55 and 1961, tying for first place at Nottingham 1954 and coming third equal in a very strong Championship at Aberystwyth 1955, which earned me a place as Board 6 on the English team at the Moscow Olympiad in 1956, where I only drew against Luxembourg, and lost to Geller, but drew in two cases from bad positions with Johner, Sanguinetti and Ghitescu.

In l96l I moved up to Derbyshire, where – though playing top board for Manchester as well as the county – having switched to Maths teaching after several years part-time study at Birkbeck and acquired offspring as well as promotion, I also started annual visits to Dartington Summer School of Music, now totalling 38 out of a possible 40, all of which made it virtually impossible for me to play in tournaments, apart from the odd visit to Hastings or fairly strong week-end tournaments, e.g. Ilford, which I won for the second time in 1973, beating Basman. My responsibilities on my return to London as Head of Charlton School in 1967, where I got Bob Wade to teach chess as part of mathematics in the Lower School, and then of Forest Hill School, where we organised many tournaments, although I played generally as top board for Kent, whom I led twice to victory in the County Championship in 1975 and 1976, meant that I had even less time for tournament chess, except at Islington and in the Challengers, so that my real heyday ended there, with a final move to a ‘quiet’ county, Shropshire – as far as chess was concerned – as Adviser for Secondary Education and Area Adviser, 1976-82, in which capacity I avoided as much paper-work as I could and taught chess in the lunch-hour to all the primary and handicapped pupils I visited. I should say most of my successes at chess have been at County Level, where I played top board for Cambridgeshire and London University, as well as the counties mentioned, and in the very strong London League, as far as I can estimate I had a success rate of some 70% in those contests. In general the games in this book, with one or two exceptions for historical or anecdotal reasons, were played at high levels, and won by the right player, not suddenly lost by a blunder, like some games published nowadays because the blunder is perpetrated by a famous player.

With regard to the general assessment of players and tournaments, I have only one comment “Look at the games!” When even, or especially, David Bronstein wails “They give me a number”, I think it time to end a spuriously precise system and revert to the earlier English practice or the traditional Soviet one of putting players in classes, preferably according to a sufficiently large number of results in tournaments or strong club or county matches. And when players are inhibited, when the match is won, from offering an opponent, who has played well, a draw, that is a diminution of sportsmanship, so a draw, even with Kasparov, should not count in grading. Finally the use of seconds or computers once a game is started should be

regarded as totally unsporting, and players should be put on their honour, as bridge-players are in matters of cheating, not to use them.

I should like to dedicate this book to the memory of my good friends, David Hooper, Stuart Milner-Barry, and A.R.B.Thomas, men of integrity, humour, and many other talents, who brought to their chess the same qualities of courage and sportsmanship they showed in the rest of their lives.

Alan Phillips

British Master, Joint British Champion 1954

Thorn Cottage, Appleton Thorn, Warrington, Cheshire

September 2003″

Here is his obituary from The Times of London

I arrived at Dartington music summer school in 2007, having driven straight from the British at Great Yarmouth, where I had come joint second in one of the minor sections. In the café I found an elderly chap with a chess set. I offered him a game, thinking this wouldn’t take much time. I was right, but not as I had anticipated. After about a dozen moves he announced I was completely lost, which he went on to briefly demonstrate. It was only at that point he casually mentioned he had jointly won the British in 1954 ( two years before I was born). Suitably humbled, I then bought a copy of his book on post war British chess, which he produced from his bag. My only meeting with Alan Phillips.