From the Siles Press web site:

“Silman’s Chess Odyssey is International Master Jeremy Silman’s homage – part instruction, part history, part memoir – to the game he loves. The book opens with with behind-the-scenes tales of tournament life. Then it profiles the lives and careers of eleven legendary players-Adolf Anderssen, Ignatz Kolisch, Johannes Zukertort, Siegbert Tarrasch, Wilhelm Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, Frank Marshall, Rudolf Spielmann, Alexander Alekhine, Salo Flohr, and Efim Geller-with the help of diagrams and analysis of over 275 games. After that it delves into accounts of criminals who were talented chess players, discusses a memorably odd series of games in a historic interzonal tournament, and memorializes some of Silman’s friends in the chess world. It concludes with material on openings, imbalances, tactics, and psychology, and FAQs”

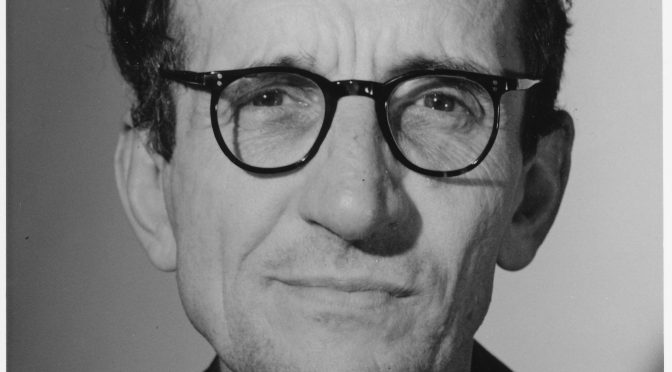

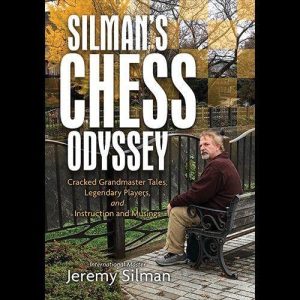

About the Author:

“Jeremy Silman is an International Master and a world-class teacher, writer, and player who has won the American Open, the National Open, and the U.S. Open. Considered by many to be the game’s preeminent instructive writer, he is the author of over thirty-seven books, including Silman’s Complete Endgame Course, The Amateur’s Mind, The Complete Book of Chess Strategy, and The Reassess Your Chess Workbook. His website (www.jeremysilman.com) offers fans of the game instruction, book reviews, theoretical articles, and details of his work in the creation of the chess scene in the movie Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.”

From the author’s preface:

As I sit down to write this preface I find myself at a loss for words. Why? I’ve been writing about chess for over fifty years (as well as teaching and playing), but every paragraph I start to write seems as f I’ve written or said it a thousand times before.

I ask myself what are my current thoughts on chess. For example, computer chess engines are monsters. Humans have no way to beat them, and they will get better and better.

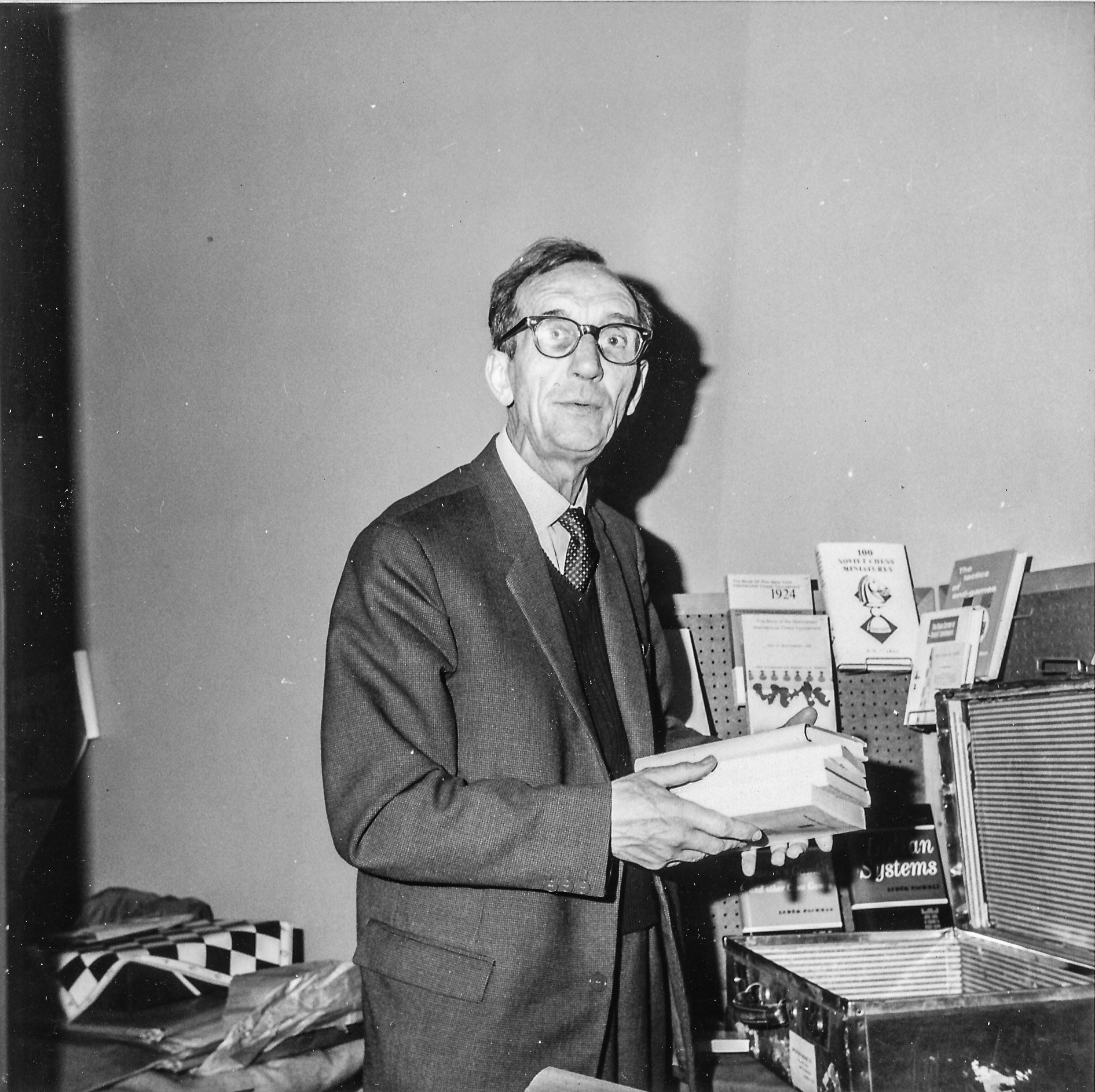

Chess continues to be a part of everyday as I must feed my habit? I very much enjoy the game when I play blitz against other masters. Sadly, several of my close friends (my chess posse) have died: Igor Ivanov, Walter Browne, Pal Benko, Steve Brandwein (I can still hear Steve chanting, “I came, I ate, and I left”), and John Grefe, and I miss there banter. I enjoy chess teaching (if the student is really engaged) and I have a handful of students. But mostly I love, love, love chess books.

Fantastic: so do I. Wait a minute, though. ‘I miss THERE banter’? While I’m at it, I’m not sure what that question mark is doing at the end of the first sentence in that paragraph. Although I share Jeremy’s love of chess books, I hate, hate, hate spelling, grammatical and factual errors (especially those in my own books and reviews).

To be fair, it does get a lot better: perhaps the preface was written after the grammar checker had read the rest of the book.

Jumping forward a bit:

I love chess history. For example, Gioacchino Greco – he was the best chess player in the world circa 1620. You must look at his games (see part four)! Greco was a master of tactics, positional play, and openings – he did everything! I Greco knew “imbalances” (which I created) he would be a chess god. As for Philidor (in the 1700s), Greco would destroy him.

Interesting, and perhaps a controversial opinion, quite apart from the question as to whether Greco actually played the games in his book. If you’re a historian of early chess, what do you think?

Further again:

And I am constantly amused by the endless stories. One of my favorites is the account Steinitz wrote following his physical battle with the hard-drinking Joseph Henry Blackburne (who was also known as the Black Death).

“After a few words Blackburne pounced upon me and hammered at my face and eyes with fullest force about a dozen blows … but at last I had the good fortune to release myself from his drunken grip, and I broke the windowpane with his head, which sobered him down a little.”

I laugh every time I look at this, as I hope you do when you read some of the stories squeezed in between the history and instruction within these pages.

There are so many sides to chess: You can have fun with it. You can study for long hours every day and become a strong player (that was my path). You can be a bad player, but just love the game and feel joy when you sit down at the board. You can be a five-year-old kid (boy or girl), or a ninety year old that plays every day.

I hope that every chess player will find some part of this book that speaks to them.

Here we have, then, an author with a distinguished record of writing instructional books, but who also has a passionate love of chess. If you share that passion you’ll want to read this book.

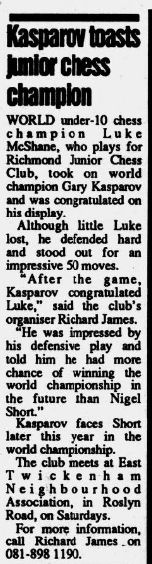

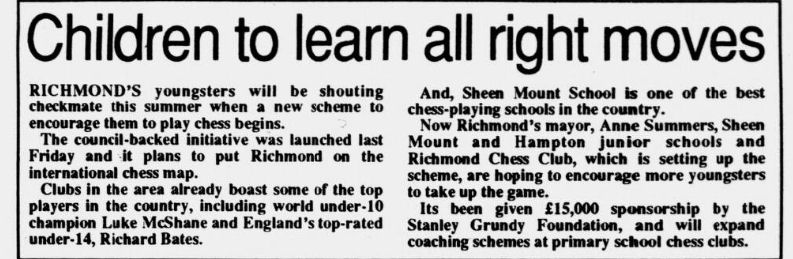

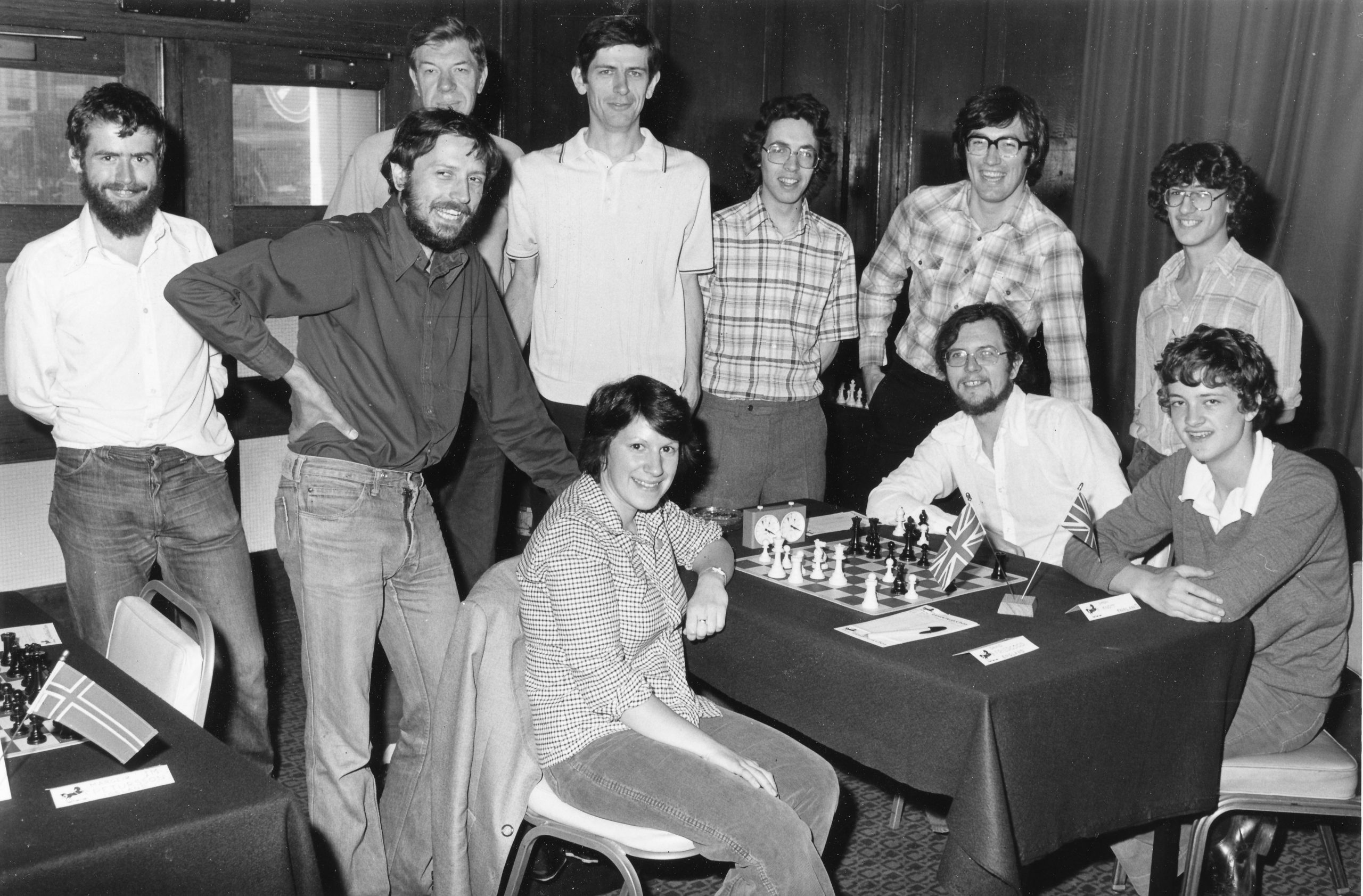

The first part, taking you up to page 56, offers Cracked Grandmaster Tales, amusing anecdotes which Jeremy himself either witnessed or was part of.

Here’s Filipino GM Balinas drinking a cup of honey mixed with tea – and losing horribly. Here’s Tal visiting Disneyland (his favourite ride was Pirates of the Caribbean). Here’s Najdorf, well, being Najdorf. Here’s Larsen, well, being Larsen and telling his favourite stories. All great fun, although I’m not sure everything would pass a sensitivity reader.

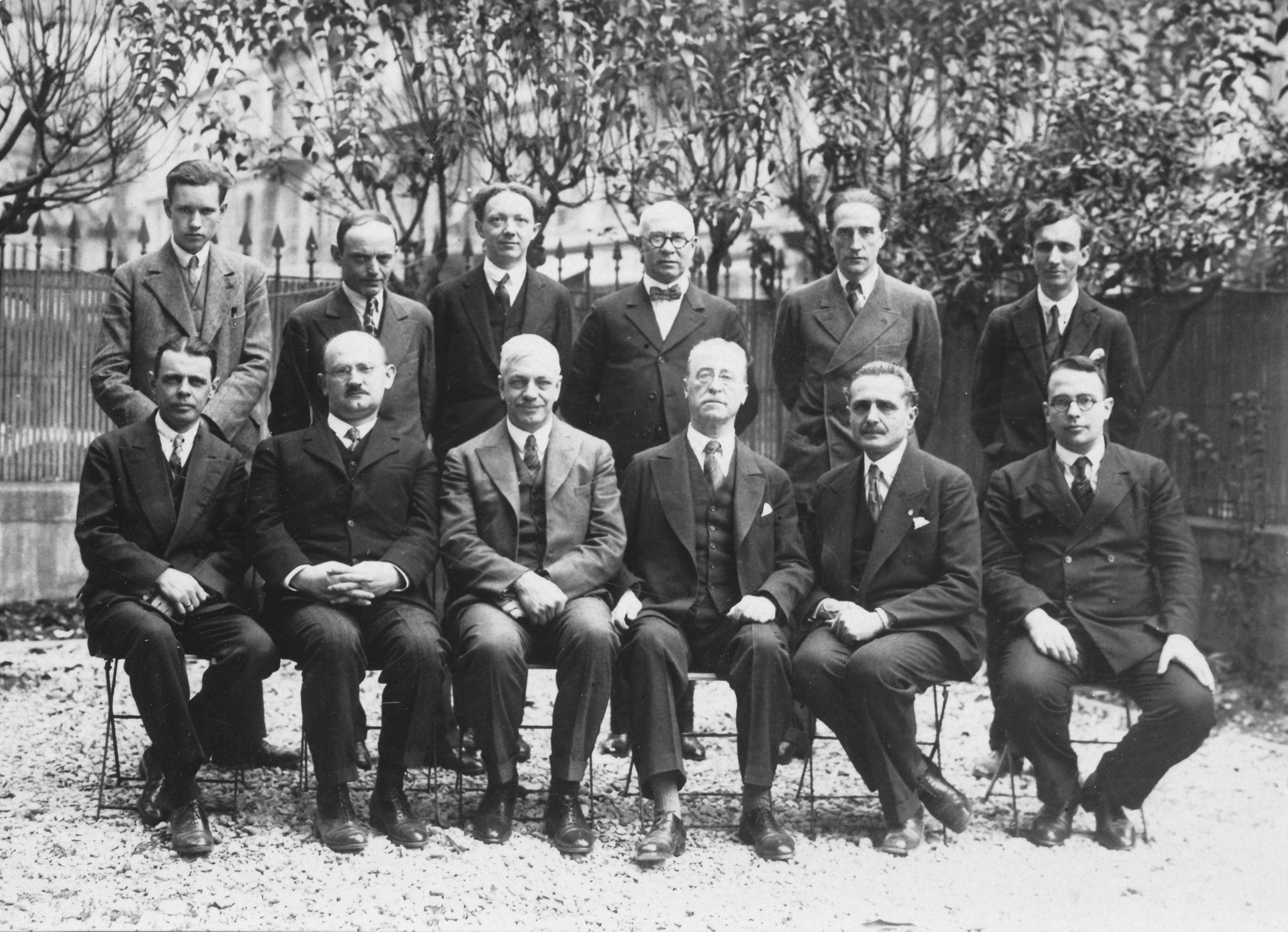

The bulk of the book, up to page 376 is taken up by Part 2, where Silman introduces you to his 11 favourite players of all time, mostly from the 19th and early 20th centuries. A pretty eclectic bunch they are as well, but with tacticians predominating: Anderssen, Kolisch, Zukertort, Tarrasch, Steinitz, Lasker, Marshall, Spielmann, Alekhine, Flohr, Geller). There’s a lot of variance in the number of pages allotted to them. Poor Zukertort only gets six pages, compared to Lasker’s 50, Marshall’s 67 and Alekhine’s 72.

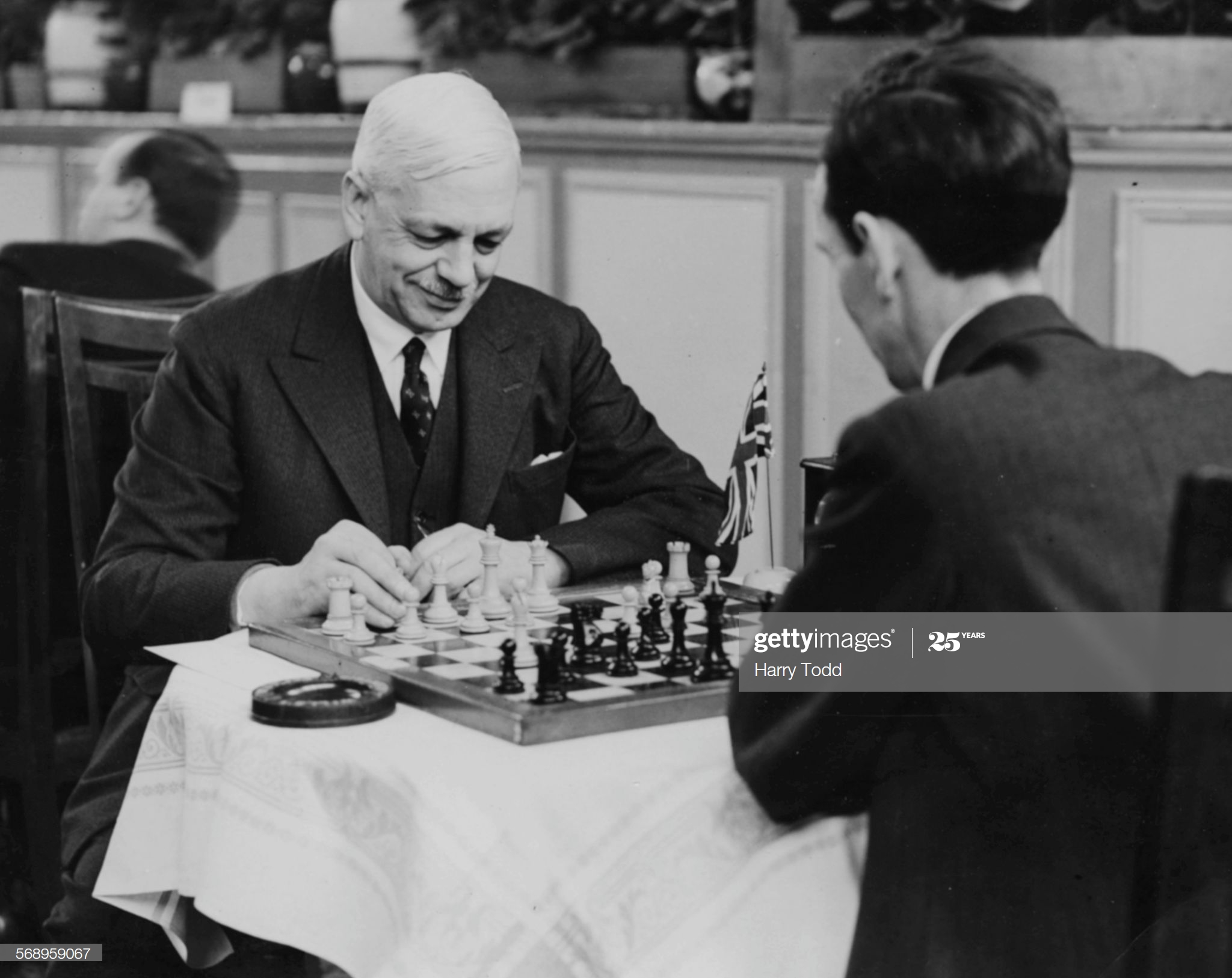

Marshall’s chapter is, as you would expect, hugely entertaining. Silman offers us a lot of games, a few with Marshall’s annotations, some lightly and often amusingly annotated by Silman, and others without annotations, as well as a run-through of his career record.

He describes this rather inaccurate game, against Janowski, as a thrilling battle. As always in my reviews, click on any move for a pop-up window.

The annotations aren’t entirely accurate, either, if you consult Stockfish, or, for the last few moves, tablebases. The rook ending is certainly worth your attention if you like that sort of thing.

The chapter on Alekhine is also fun, although some readers will have seen some of the games many times before.

This game has a British interest, although I have a slight quibble. Milner-Barry was usually known by his middle name: Silman only gives his first name here.

There’s a more serious problem when we reach 1938.

Silman presents this Famous Miniature, but mistakenly attributes the black pieces to Rowena rather than her future husband Ronald Bruce.

This mistake still appears in some online sources, and earlier versions of MegaBase had it wrong, but it’s correct in the current version. This article sets the record straight.

Silman also fails the Yates test: he was just Fred, not Frederick (and MegaBase, frustratingly, still hasn’t picked this up). Silman is a lover of chess history, but, like many others, not a historian. You might equally well argue, I suppose, that not all chess historians actually love chess history, being interested in facts at the expense of character.

Part 3 is entitled Portraits and Stories. Here we have some chess-playing criminals such as Norman Whitaker and Claude Bloodgood, who will be familiar to readers of The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict.

Silman also pays tribute to a few of his departed friends. Here, I was struck by his memories of Steve Brandwein, an exceptionally strong blitz player who played very little over the board.

Here’s one of his games.

Part 4 is a real miscellany: Musings, Theory, Instruction, and FAQs. You’ll find all sorts of things here, including this classic game. It taught me a lot in my early teens, and improved my positional understanding by leaps and bounds. Perhaps, with Silman’s annotations, it will improve your positional understanding as well.

There’s so much more here: the aforementioned Greco games, chess psychology, some opening theory, answers to questions such as ‘Can Anyone Become a Grandmaster?’ – and the Greatest Amateur Game of All Time.

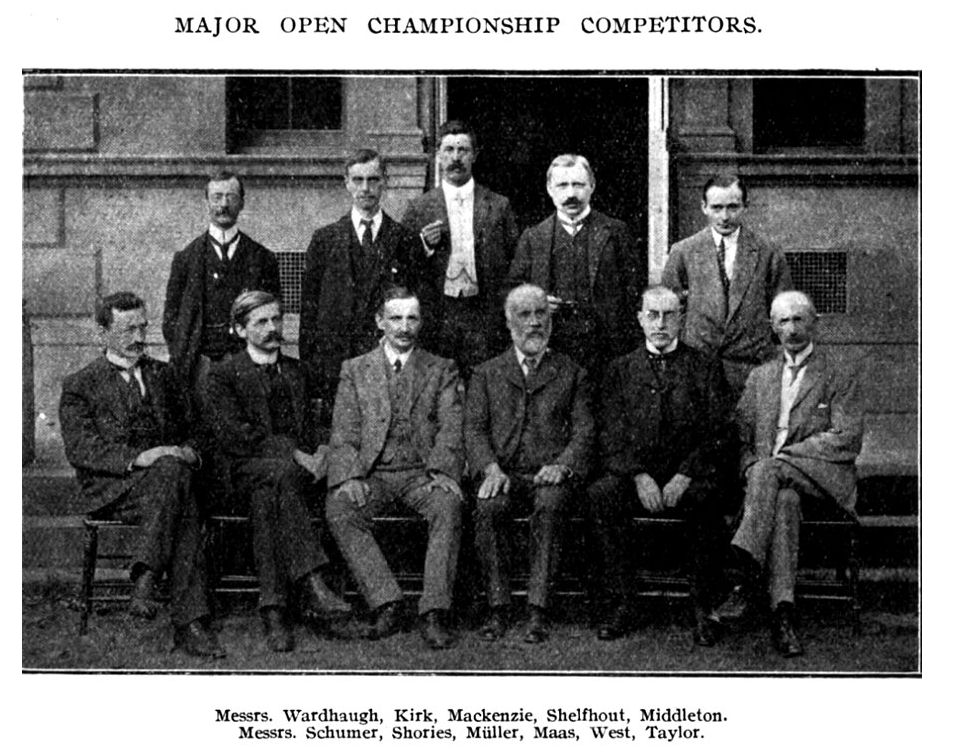

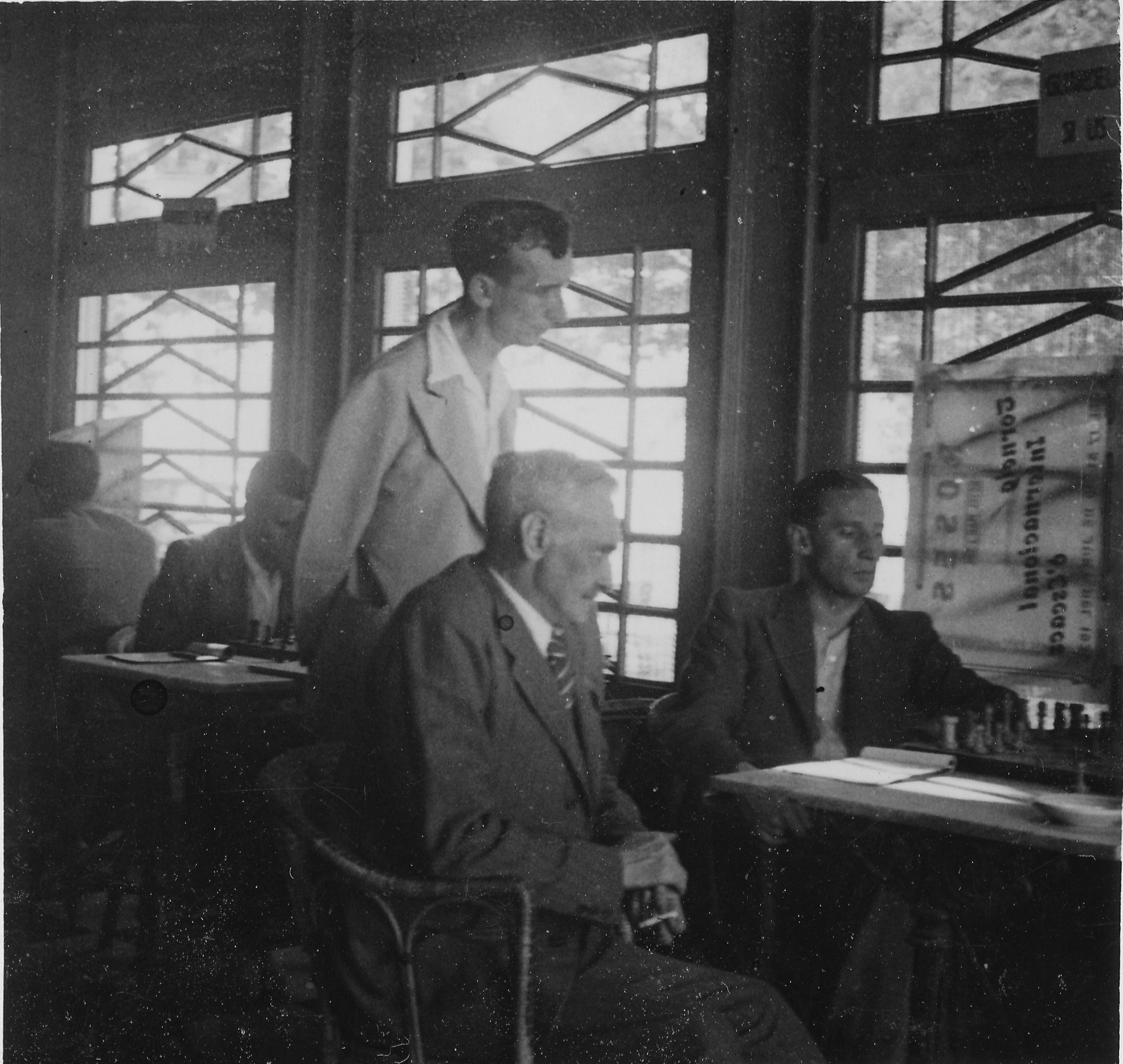

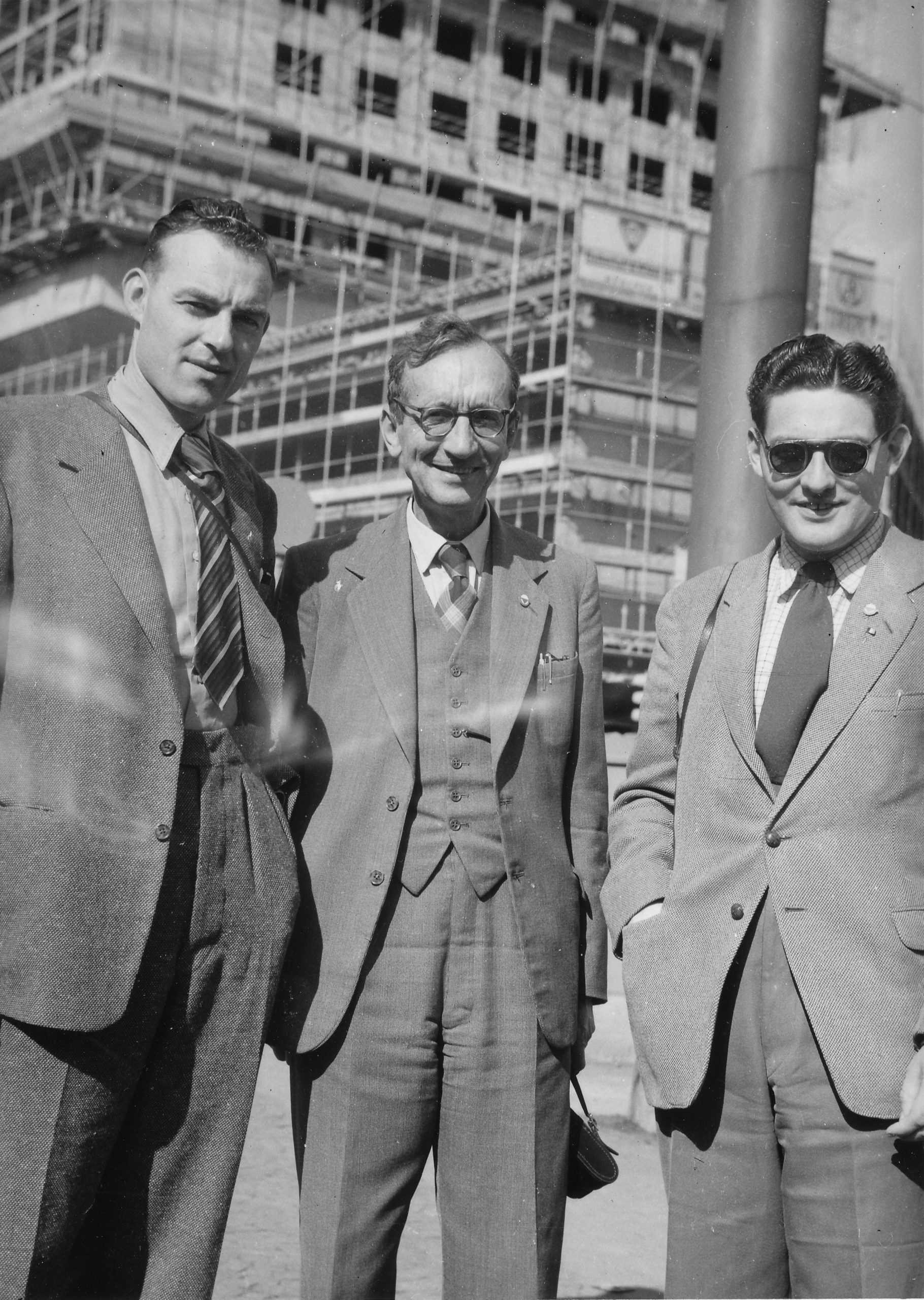

You might think there are at least two books struggling to escape from this heavy, well produced, entertainingly written and beautifully illustrated (a wide range of great photographs throughout the book) volume. Part 2, Silman’s First Eleven, might be compared with Chernev’s Golden Dozen, while Parts 1, 3 and 4 would make a great collection of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess. And, yes, I think I can see the great Irving’s shade smiling down in approval.

You might see it as a bran tub, a lucky dip. Turn to any page at random and you’ll find something to amuse, inform or instruct.

Despite some avoidable errors, which will probably annoy you less than they annoy me, this book is highly recommended to all true chess enthusiasts, whatever their rating. It’s Jeremy’s love letter to the game that has meant so much to him throughout his life, a paean to the beauty and excitement of chess. If anyone out there thinks chess is a dull game, or chess players are dull people, this is the book to disabuse them.

In his chapter on Geller, Silman writes:

In my mind, if you don’t know all the greats from the past, then you’re missing the heart and soul of what chess is about. So many wonderful games. So many stories; some funny, some crazy, some very, very sad.

I’m in complete agreement: what sets chess apart from other games is its history, heritage and culture. If you agree as well, or if you’d just like to investigate further, then you should certainly read this book.

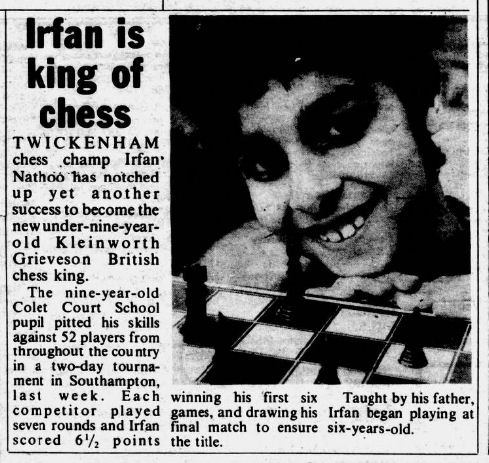

Richard James, Twickenham 7th February 2023

Book Details :

- Paperback: 550 pages

- Publisher: Siles Press (US) (31 May 2022)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:1849947511

- ISBN-13:978-1890085247

- Product Dimensions: 17.78 x 3.81 x 25.4 cm

Official web site of Siles Press