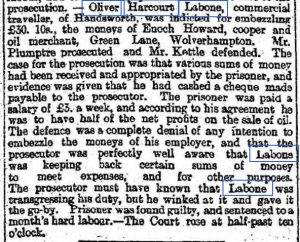

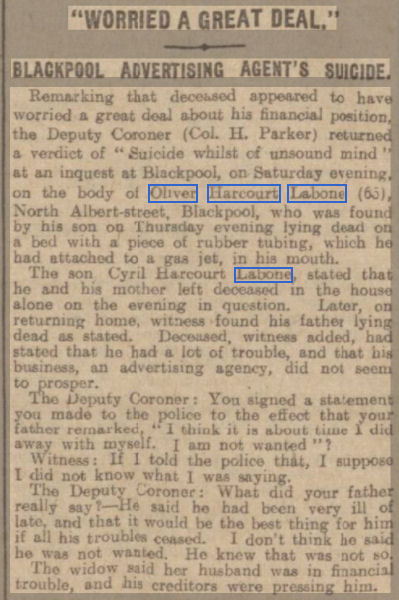

Last time I wrote about Oliver Harcourt Labone. Further research has revealed more information about his mother and both his (probable) biological and step-fathers, along with further coincidences. No chess, this time, I’m afraid, but some great stories.

Let’s start with Richard Austwick Westbrook. He was a solicitor, born in 1815: his father, also Richard, would, on at least two occasions, hit financial problems. He married in 1841 and had four children, but his wife died in 1852.

At that point he employed Anne Topley, the daughter of a canal agent from Long Eaton, Nottinghamshire, as a governess for his children, bought another house and instructed her to bring up the children there while also running it as a boarding house. At some point, Richard and Anne started an affair. On 20 May 1854, an Arthur Westbrook, son of Richard Austwick and ‘Annette’ was baptised at St Mary’s Paddington, but there’s no matching birth record and no further evidence of him. On 18 May 1855 they married clandestinely at St Paul’s Hammersmith, and two sons were born: Rowland Martin in 1857 and Oliver Harcourt in 1858.

At some point things started to go wrong. Richard moved into lodgings with Janette Cathrey while Anne took an interest in one of the lodgers in her boarding house: a Greek merchant named Nicholas Demetrio who had moved there in 1857. It’s possible, I suppose, that Nicholas rather than Richard was Oliver’s biological father.

The Demetrio family, it seems, had been running dodgy businesses for years. The company was started by Nicholas’s father and seemed to involve his brother Antonio, perhaps another brother, Gregory, and possibly another brother as well. They apparently had branches in Trieste and Cairo as well as London and Liverpool. Looking at passenger lists of ships coming into England, there are various Demetrios there, including a Demetrio Antonio Demetrio, who might have been either Antonio or their father, claiming various nationalities including Italian and Austrian. It’s quite possible, as we’ll see, that they were using various pseudonyms as well, perhaps including Labone.

In August 1859, however, Demetrius Antonio di Demetrio was declared bankrupt, ‘having carried on business as a merchant, in the Greek trade, under the title of Messrs. A. di Demetrio and Sons. It’s not at all clear to me exactly how many Demetrios there were.

Meanwhile, Nicholas encouraged Richard to move up to Liverpool to start a company there which would bear his name, but would actually be run by the Demetrios. While he was away, ‘intimacy took place’ between Nicholas and Anne, and in 1860 a son, Clement Leslie, was born, with the birth record giving false surnames for both parents.

And then, at the end of March 1860 there was an extraordinary court case held just down the road from me in Kingston. If you have access to online newspaper sites I’d encourage you to look up Whitmore and others, Assignees, v. Lloyd. The reports make hilarious reading. Basically, the Demetrios’ creditors were trying, unsuccessfully as it would turn out, to get their money back. It was claimed that Antonio and his brother Nicholas were setting up bogus companies in various names such as Lebous (not all that far from Labone), Dalgo (not all that far from Clement’s birth surname Dalba) and Lambe. Likewise, the company Richard Westbrook was setting up in Liverpool was equally fraudulent. Anne Westbrook was involved in all this, as was a friend of hers named Mary Anne Bridget Martin, both of whom gave evidence in the case. I can find nobody of that name in that area in the 1861 census or anywhere else, so she might also have been a fraud. We’ll meet her again later.

Neither Antonio nor Nicholas was present at the hearing: both had apparently disappeared without trace. Of course we now know that Nicholas was, by 1861, living in Glasgow under the name Labone.

Moving swiftly forward, we reach June 1861, when the divorce courts heard the case Westbrook v Westbrook and Demetrio. Richard was suing Anne for divorce because of her adultery with Nicholas. He, it was believed, had left the country (yes, he was in Scotland) and did not appear. As always in those days the court decided it was the woman’s fault and granted Richard a decree nisi. Nicholas’s name appears in court reports as ‘Nicolas Antonio di Demetrio’ which prompts the question of whether Nicholas and Antonio were the same person.

About this time Anne must have moved up to Glasgow with Rowland, Oliver and Clement to join Nicholas, where they lived as husband and wife. Anne was now calling herself Annie Mary Labone, and giving her maiden name as Copley rather than Topley. Nicholas set up business as a Professor of Languages, teaching French, German and Italian, and in 1862 their daughter, Flora, was born. Again, things didn’t work out: in November 1863 he was declared bankrupt, and worse was to come when their baby son Gregory, named after one of his possible brothers, was born prematurely and died after only 36 hours.

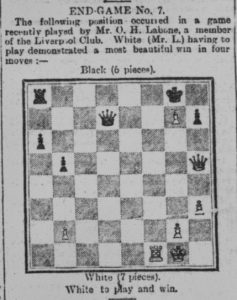

We find the family in the 1871 Scottish census, by which time Nicholas had joined Glasgow Chess Club and, apart from playing on a high board, was very much involved in the club’s administration. But at some point fairly soon afterwards they split up and, separately, moved down to the Liverpool and Manchester areas. At some point he might have resumed his chess career: a player named Demetrio represented Manchester against Liverpool in 1881 and 1883.

Annie now came up with a new idea to make money: for thirty years she would send begging letters to newspapers and magazines asking for charity for her elderly and infirm friend, Miss Mary Ann Bridget Martin – the friend from the 1861 court case – and selling various quack remedies. In 1879 she was running a seminary for young ladies in Birkenhead. A professor of languages at the school, one Charles M Grabmann, was accused of assaulting an elderly cook who had refused to make pea soup, but the case, predictably, was dismissed. I can’t find anything else about Grabmann, whoever he was. Perhaps yet another fraud. In 1882 she was declared bankrupt, described as a widow and former schoolmistress.

But she wasn’t a widow at all: Nicholas was still alive and well. He was living in Barrow-in-Furness, where, also in 1882, he married a teenage girl named Ellen or Helen Bowkett. (In those days Ellen and Helen were interchangeable, which reminds me of another Minor Piece I intend to write at some point.) He’d also changed his name again, to Demet, a shortened version of his real surname. Shortly after the marriage they moved to Manchester. According to the birth records they had four sons between 1885 and 1891, followed by a daughter in 1897. The 1891 census lists an older son, Broderick, born in about 1883 but there’s no birth or any other record for him. He claims to be aged 53 (he was certainly several years older), a Professor of Languages and born in Versailles (who knows?). He was still there and still in the same occupation in 1901, but by 1911 he wasn’t at home. Helen was there, claiming to be married rather than widowed, and telling us they’d had six children, all of whom were still alive, but there’s no sign of Nicholas and no death record has yet been found. Anne, meanwhile, had died in Liverpool in 1899.

Returning to London and the year 1861, just a few weeks after the divorce, Richard, during an argument at the kitchen table following a visit to the opera, threw a table knife at Janette Cathrey, ‘an extremely portly woman’ with ‘a protruding belly’, who may or may not have been his mistress, hitting her in the abdomen and causing a fatal injury. A first trial found him guilty of manslaughter, but a second trial cleared him. Just a year later he married again, to Emma Louise Shipman, who was more than twenty years his junior. Richard and Emma had two sons, Henry and Alexander.

In 1881, Henry was a law student: it must have been intended that he would follow in his father’s footsteps, but he would eventually choose several very different careers. By 1891 he’d moved to, guess where?, Leicester, where he and Alexander were running a pub. Alexander had married and had three young children. In 1901 Henry was still in Leicester, but now working as a printer’s clerk. He’d married a widow with two young children, but Alexander and his family are nowhere to be found. Perhaps they were abroad.

By 1911 Alexander and his family were in Brixton. He was now working as a Variety Agent, with his son helping him and his two daughters employed as dancers. They were doing well enough to afford two domestic servants. Henry was still in Leicester, and in the same business as his brother. He was described as a Music Hall Manager, and was living with his wife, his step-daughter and his widowed mother.

If you check his address, he was just half a mile, or thereabouts, away from Oliver Harcourt Labone, his presumed (assuming Richard was indeed his father) half-brother. Quite a coincidence. I presume neither of them had any idea. If either of them had walked a mile or so to the south, they could have visited the Victorian terraces of Sheridan Street, the home of Tom Harry James. He was a house painter living with the five youngest surviving children of his first wife (there were 12 in total). He’d just remarried and would go on to have another six children, the youngest of whom, Howard, was my father.

And there’s more. Henry Westbrook’s first wife died in 1913, and in 1920 he married another widow, Matilda Manger, who had been born Matilda Cort in Market Harborough. Now Cort has always been a common surname in the Leicester and Market Harborough areas, and there are many in my family tree. One particularly interesting branch, related to me by marriage, for example, goes back to Benjamin Cort who was born in nearby Great Bowden in 1644. Now Matilda was the daughter of Charles Cort, who was in turn the son of Robert. At the moment I can’t take this back any further as there were several Robert Corts born in Market Harborough at about the same time. But it’s reasonable to assume that Matilda was from the same family as the Corts who married into my family at various points. So perhaps I can claim a connection, via a couple of marriages or so, to Henry Westbrook, and therefore also to Oliver Harcourt Labone.

It’s quite a story, isn’t it? All three of them, Richard, Anne and Nicholas, seemed to be crooks, fraudsters, con artists, liars and more, and all regularly in financial trouble. You really couldn’t make it up. It’s hardly surprising that Oliver had so many problems in his life.

Nicholas, for all his faults, was clearly a highly intelligent and well educated man, fluent in several languages and also a reasonably proficient chess player. Perhaps it required the skills of a chess player to set up the elaborate fraud upon which his first business was based. Anne seemed to have a knack of falling for unsuitable men. Richard was, among other things, a violent, if unintentional, killer.

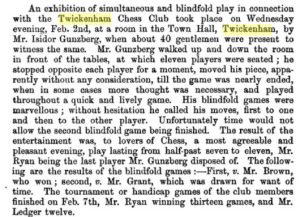

You’ll meet my grandfather’s family again another time, but for now it really is time to return to Twickenham, and perhaps some more chess.

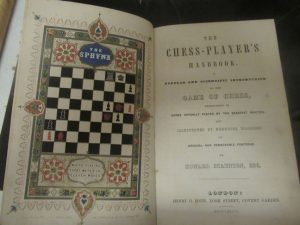

If you’ve read my article about

If you’ve read my article about  There are also two inscriptions. The second is ‘Peter Elliott’: there were several people of this name in this area, none of whom mean anything to me.

There are also two inscriptions. The second is ‘Peter Elliott’: there were several people of this name in this area, none of whom mean anything to me.