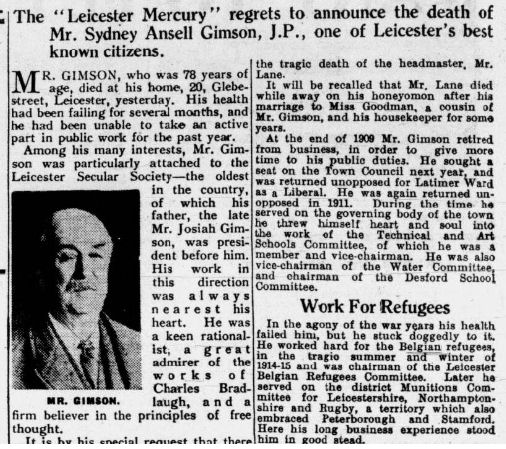

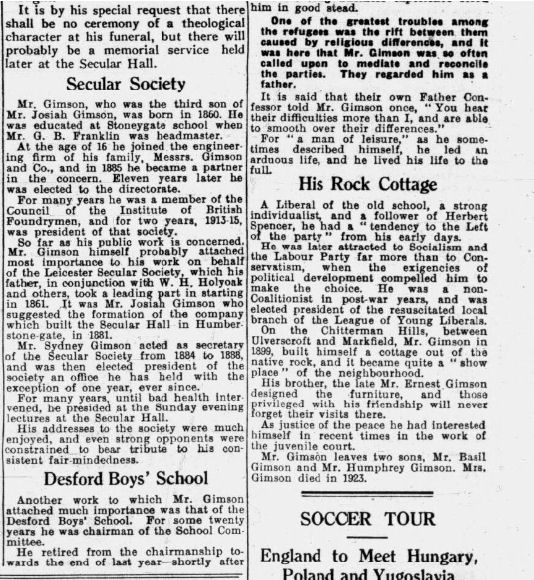

Last time I looked at chess in Desford Approved School in the 1930s, introducing you to the two men behind the project: school superintendent Cecil Lane and local politician Sydney Gimson.

Unlike most at the time, they took a ‘nurture’ rather than a ‘nature’ view of behaviour, believing that the boys in their care had had a difficult start in life, and, if they were treated well, the vast majority of them would go on to lead good lives. Indeed, Gimson claimed on several occasions that almost all their former students kept out of trouble on leaving Desford.

They would have understood the words of Phil Ochs in his song There But For Fortune three decades later:

I’ll show you a young man with so many reasons whyThere but for fortune go you or I

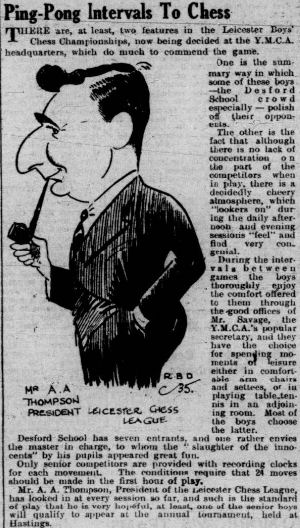

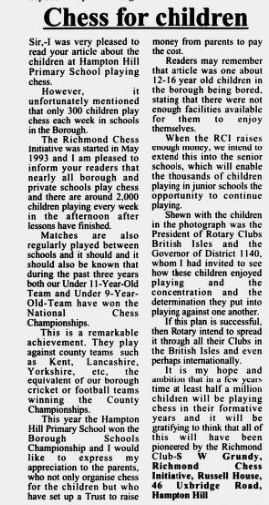

Chess played an important part in life at Desford, and was greatly valued within the school. It’s fashionable these days to promote chess in schools for its perceived extrinsic benefits, both cognitive and social, and there is also much great work being done promoting chess in prisons throughout the world. Lane and Gimson, you might think, were 90 years or so ahead of their time.

You can see how it might work, can’t you? At one level chess, along with similar games, is an exercise in decision making. If you want to make good decisions, in chess or in life, you have to control your impulses, consider your options, think about the effect of your choice on other people, and work out what might happen next.

If you make good decisions when you’re playing chess you’ll win your games. If not, you’ll lose your games. If you make poor decisions in life you might end up in Approved School or in prison.

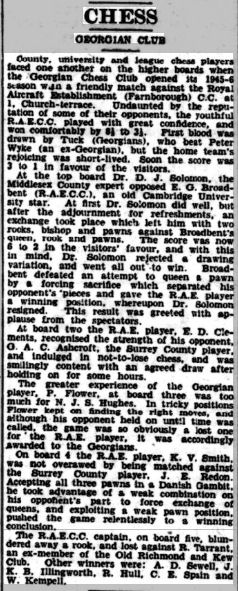

The régime in Desford was, as you saw in my previous article, very enlightened for its time, and, in some respects, enlightened even by today’s standards. The chess reports usually only gave the initials of the players, but in some cases we can find their first names from elsewhere, especially for those boys who reached the finals of the school’s annual boxing championship.

If they have distinctive names it’s possible, through sources such as censuses, electoral rolls, birth, marriage and death records and newspaper archives, to find out more about their circumstances and their lives after Desford.

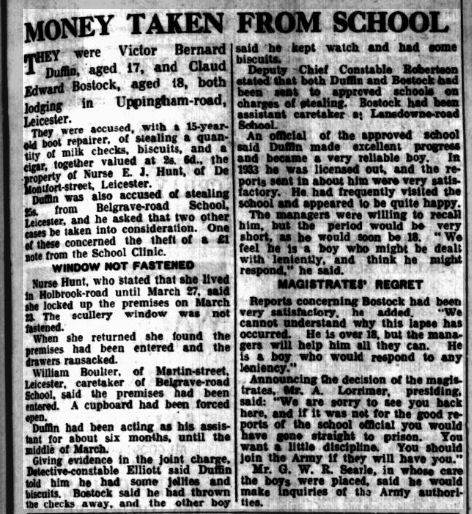

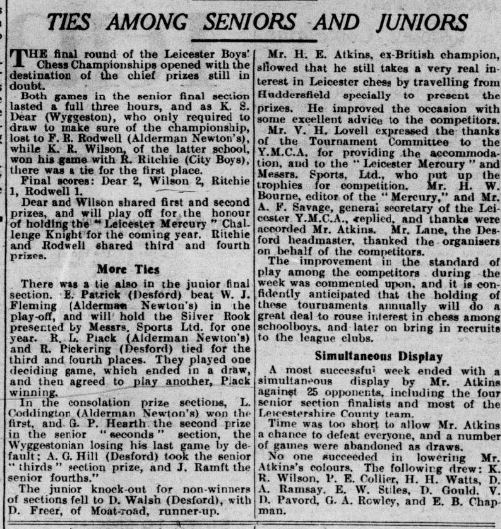

Take, for example, Victor Bernard Duffin, who played in the senior section of the 1933-34 Leicestershire Boys’ Championships.

Victor was the younger of two brothers from a seemingly respectable family from Biggleswade, born in 1917. Their father was a market gardener and seed merchant who hit financial problems and was declared bankrupt in 1920. On leaving Desford, Victor got a job as an assistant school caretaker in Leicester, but he was one of those who didn’t keep out of trouble.

In 1939 he married in Portsmouth, suggesting a possible Naval connection, with a daughter and a son being born there in 1942 and 1948. There’s also a record of an Army Cadet named Victor Bernard Duffin becoming a 2nd Lieutenant in the Artillery in 1945. Would he have been too old to have been a cadet?

After the war he became the landlord of a pub near Peterborough, remarrying in 1957. Although he was respected within his trade, becoming secretary of the Licensed Victuallers Association (I’d guess the local branch) he had further brushes with the law. He was fined for a parking offence in 1961, and, rather unluckily, for driving a car without insurance in 1956. (His team were returning from a dominoes match and he took over the wheel when his teammate felt unwell. Unused to the controls, he was stopped for driving unsteadily. He wasn’t insured for driving his friend’s vehicle: he was fined for driving without the correct insurance, and she was fined for allowing her car to be driven by an uninsured driver.) On another occasion in 1956 he was on the other side, when a customer in his pub paid for his drinks with a Bank of Funland fiver bought from a joke shop.

Victor died in 1983 at the age of 66. His brother Clifford also married twice, on both occasions to women named Doris. His second marriage took place in Market Harborough: Doris Mabel Plant was my 4th cousin once removed!

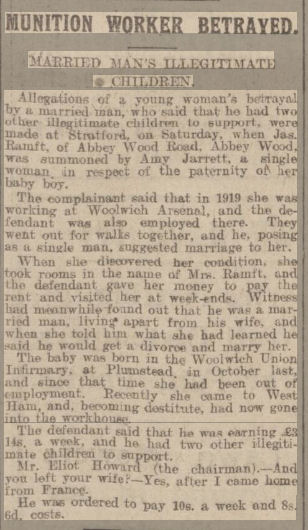

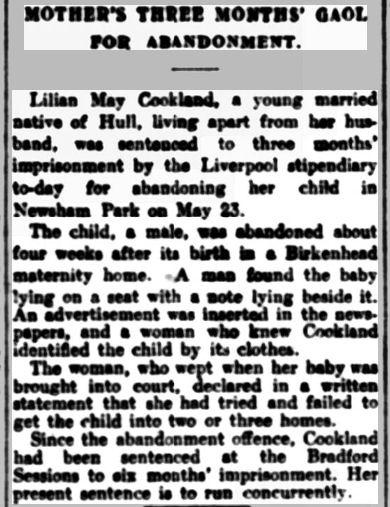

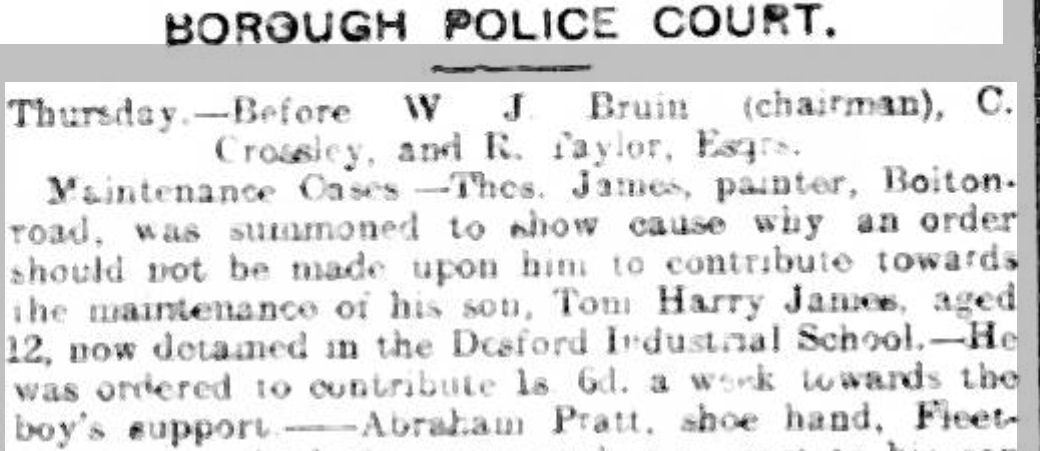

Another player we can identify from the same tournament is James Ralph Ramft. The Ramft family were originally from Germany but had been living in south east London for some time. There’s no obvious birth record for James, but this article seems to provide a clue.

It seems that he was born in 1919, so he was probably one of the two other illegitimate children mentioned here.

We pick him up in Desford at the end of 1928, taking part in the boxing tournament, so he’d been there some time. It’s possible he was taken in because his parents were unable to care for him rather than because of any criminal offence.

He made the papers through one of his chess games: two pieces down against the eventual winner, Keith Dear, he gave up his rook for a pretty stalemate.

It appears he returned to London, marrying a German girl in Woolwich in 1952 and moving to North London, marrying a second time in 1959, and, sadly, dying a few months later at the age of only 41.

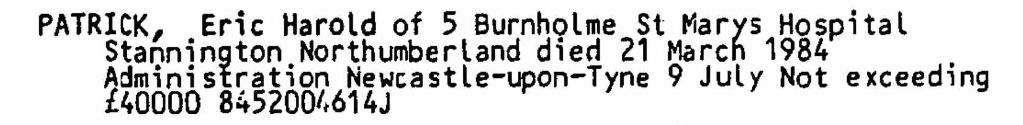

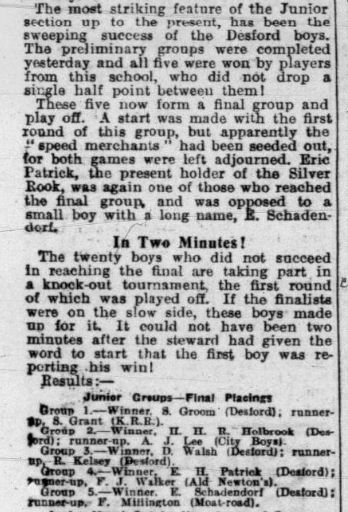

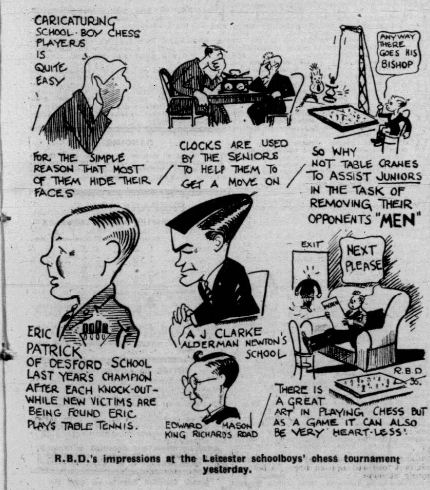

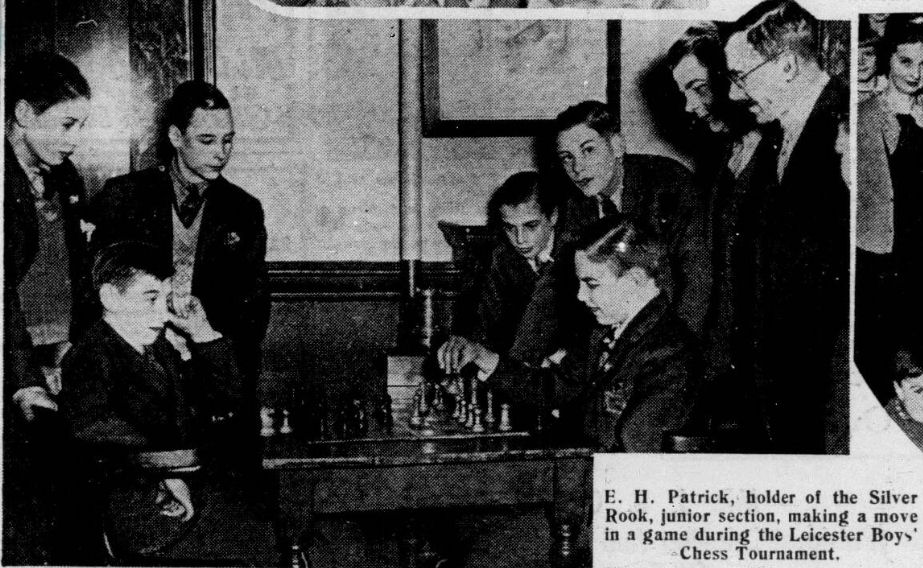

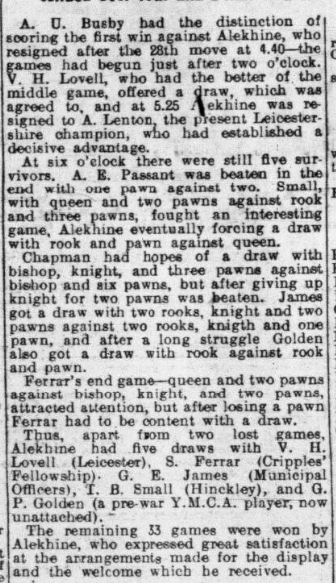

What, then, of our titular hero, Eric Harold Patrick? Last time we witnessed him winning the junior section of the Leicestershire Boys Championship in three consecutive years, and then moving on to represent the YMCA in the county league. You’d imagine a bright young man with a successful future ahead.

Unfortunately, this seems not to have been the case. There’s no sign of him in the 1939 Register, and we don’t pick him up again until 1948 when he marries Gladys Green in Northumberland. A son, named Terence after one of his uncles, is born in 1953 (he died, apparently single, in 2006). Nothing further is available until a death record in 1984. Here’s his probate entry.

St Mary’s Hospital Stannington was a mental hospital. You can find a two-part documentary on YouTube here and here.

How long had he been there? Was he there when he married Gladys in 1948? I can’t find any indication that he served in WW2 so he could well have been there most of his life. Were incipient mental health problems responsible for whatever had caused his admission to Desford? What a sad story.

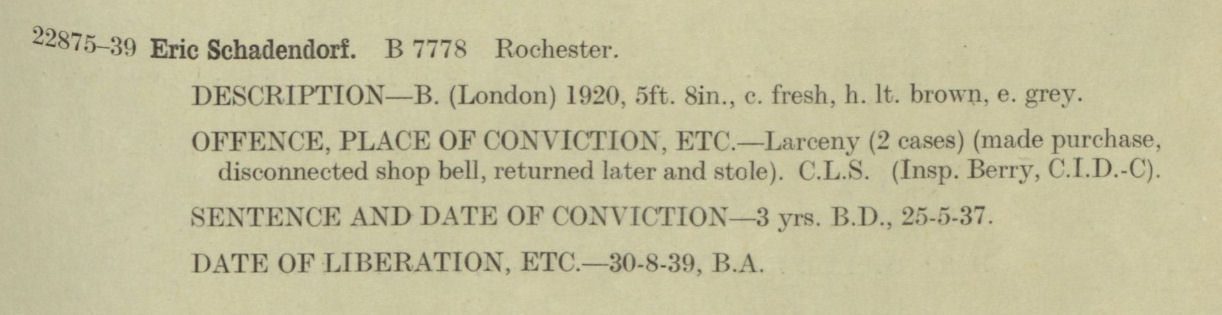

He wasn’t the only Eric playing chess at Desford. There was also Eric Schadendorf.

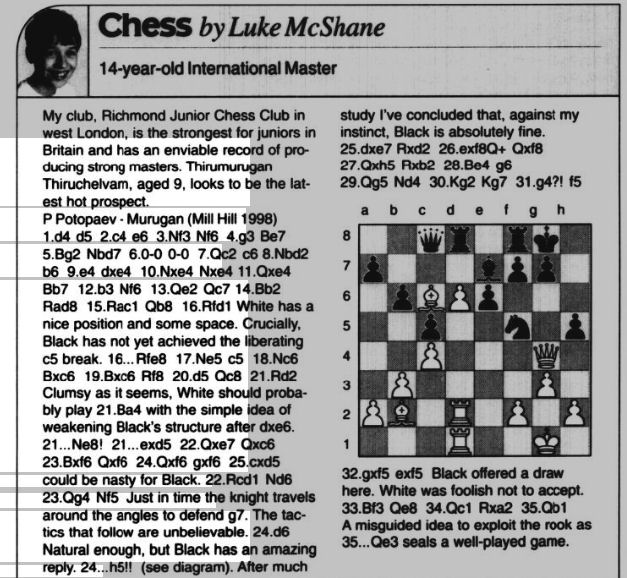

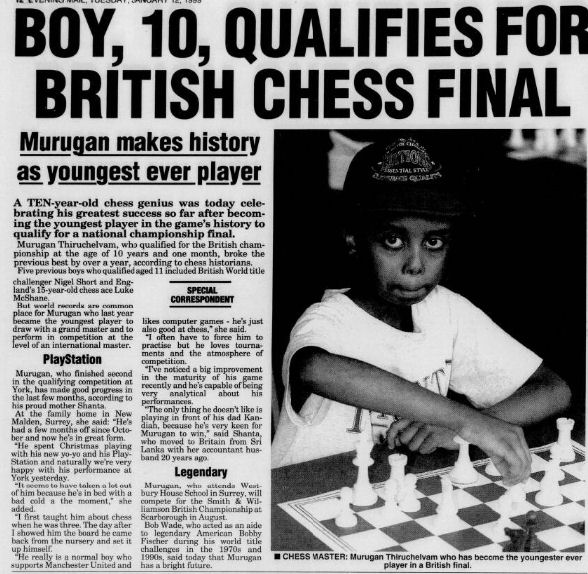

A small boy with a long name: I wonder what they would have made of Thirumurugan Thiruchelvam.

Eric, born in 1920, came from what was clearly a troubled family from South London, not very far from the Ramfts. His father, Hugo, was German, but may have been born in Belgium, and may also have had Polish connections. His mother, Pauline, was Polish. Hugo and Pauline went on to have another son, Leo, in 1928, but he died in 1929. Hugo himself died the following year at the age of only 29. Later the same year Pauline remarried: a daughter was born in 1936.

Given these circumstances it’s hardly surprising that young Eric got into trouble. Did his time at Desford help him mend his ways? Did his chess ability (he finished 3rd in the 1934-35 tournament) encourage him to think before he acted? Apparently not.

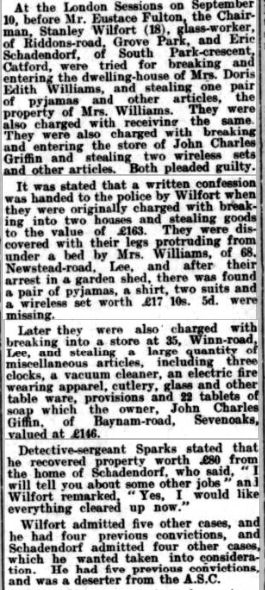

After his liberation, etc. he married Helena Wilfort, presumably a cousin, in 1940, but was soon in trouble again.

Stanley Wilfort was Eric’s uncle – his mother’s brother. The ASC was the Army Service Corps where he was working as a driver. His marriage, not unexpectedly, didn’t last.

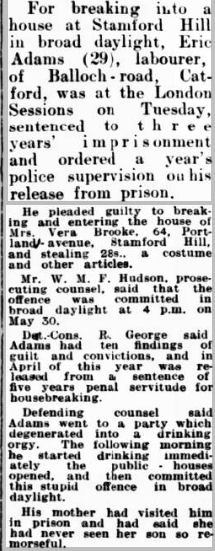

At some point he decided to change his name from Schadendorf to Adams, the name of his stepfather, but this didn’t keep him out of trouble.

It seems like he finally managed to resolve his problems, settling down with another woman in North London where they brought up a son and a daughter. He died in Islington in 1984 at the age of 63. I can only hope he found some happiness later in life.

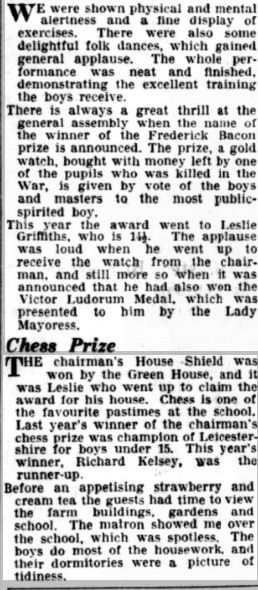

After Eric Patrick, the strongest Desford chess player seems to have been Richard Kelsey.

I’m pretty sure he was Richard Albert Kelsey, another Londoner, born in 1923 in Shoreditch, the fifth of seven children, if you believe the official records, of James William and Margaret Kelsey. His father served in the Royal Navy from 1909 to 1921 so wasn’t around much. The 1922 Electoral Roll includes no less than 11 electors in their house in Hoxton. By 1926 there were 12 electors there, including Margaret, but not James. One of them was Richard Albert Langley: it seems a reasonable bet that he was young Richard’s real father, not least because Margaret had already had another Albert. So this was a fairly large and dysfunctional family existing in very cramped conditions.

As far as I can tell, he returned to London on leaving Desford. We have a marriage in Hackney in 1944, another possible marriage in nearby Stepney in 1955 (no children from either marriage), and a death record in 1967 at the age of only 44.

Alan Wann, born in 1921, was a local boy from a working-class Leicester family who represented Desford in both the junior tournament and the league in the 1935-36 season. His later life wasn’t blameless. In 1947 he and his father were fined for stealing mushrooms from a field. In 1948 he was cited in the divorce courts when he was having an affair with a married woman. She was granted a decree nisi, later marrying Alan and having a large family. In 1958 he was fined for failing to pay his National Insurance contribution. He died in 1994: a relatively long life by the standards of the other Desford chess players.

Norman Reginald Bass (1925-1997) was only 11 when he first played in the county junior championships. He competed the following year as well, and was still in Desford at the time of the 1939 Register and taking part in the boxing in January 1940 before returning to York. Like so many of the Desford chess players he married twice, fathering six daughters.

D Bursey, who played in the 1936-37 championship, must have been Dennis Roy Bursey, born 1922 in Enfield, North London. His background was very different to that of most of the other Desford boys. His father had earlier served in the Navy, on at least one of the same ships as James William Kelsey, but by the time Dennis was born he seems to have been some sort of travelling salesman with family connections to both Canada and Australia. Returning to London after his time in the Approved School, it looks like he married three times, in 1944, 1974 and finally in 1985, shortly before his death the following year. It’s disturbing to notice how many of these boys married more than once, in times when divorce was a lot less common than it is today.

There can be few who had a less propitious start in life than Hubert Michael Cookland, as he later came to be known, but that didn’t stop him playing chess successfully at Desford.

The circumstances of his birth sound like an episode of Long Lost Family.

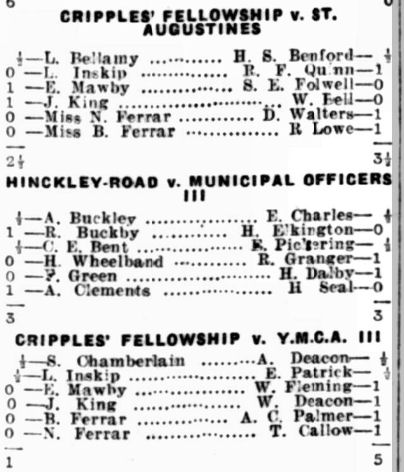

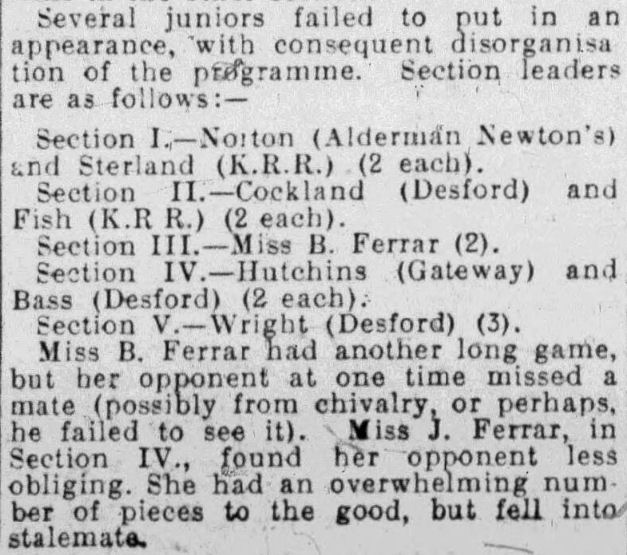

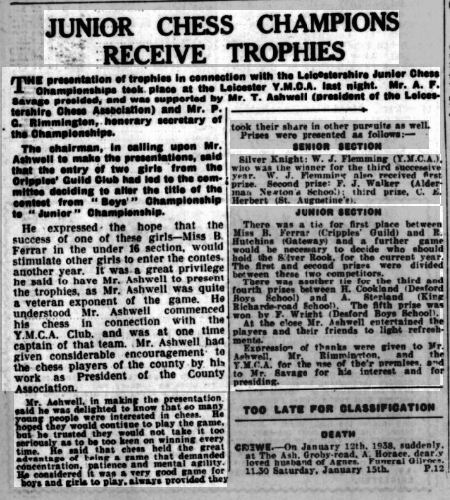

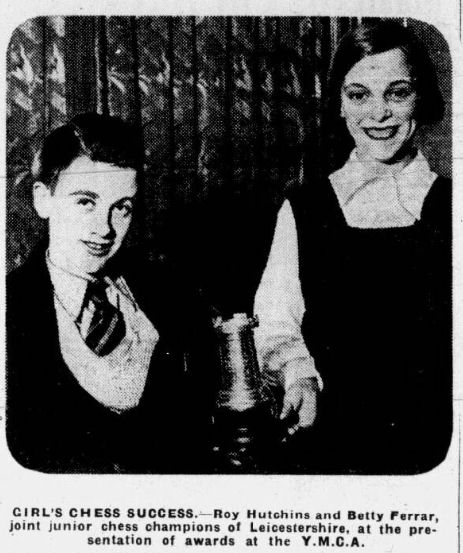

Given that sort of background it was perhaps unsurprising that he got into trouble, and also impressive that, in 1938, he was a good enough chess player to share third place in the younger section of the Leicestershire Junior Chess Championships, won, you might recall, by Miss Betty Ferrar. He was also a boxer, competing in the featherweight class at his school boxing championships the following year.

On release from Desford, Hubert took a job on a poultry farm, but, by the end of 1941, was again in trouble with the law. With the help of an accomplice, another former Desford boy, he took to stealing his employer’s hens and selling them to a chap he met in the pub. He was sentenced to six months imprisonment, and it was recommended that he should join the Navy on his release.

This is what he did, enlisting in the Merchant Navy, serving on the Arctic convoys in 1944. On leaving the Merchant Navy he returned to York, where he’d been brought up, taking a job as a driver, marrying in 1946, and bringing up two sons and a daughter. He later started working in the building trade, eventually becoming a building contracts manager. Hubert was in trouble again in 1957, for driving the wrong way down a one-way street, causing an accident in which a cyclist sustained serious injuries.

In spite of a difficult upbringing, Hubert Cookland seems to have made good in the end. Some of his story has been told by his granddaughter on an online family tree. He died in 1997 at the age of 75. I’d like to think he maintained his interest in chess, perhaps teaching his children and grandchildren.

Another Desford competitor in the 1938 tournament was Bernard Hugh Tedman, also born in 1924. Bernard, who came from South London, was another boy with a difficult family background. His father Bert, who had spent time in the workhouse as a boy, seems to have had at least six relationships as well as many different jobs. In 1919, after war service in the Royal Garrison Artillery, he was sent down for bigamy, the judge being Llewellyn Atherley-Jones, who was also a pretty strong chess player. Bernard may or may not have been the youngest of his many children.

There’s not very much more to be said: like Eric Patrick, Bernard developed mental health problems, dying at the age of 50 (his death record incorrectly gives his year of birth as 1927) in Warlingham Park Hospital, which, coincidentally or not, was where his father had been working at the time of the 1921 census. The above link demonstrates that draughts was popular there: maybe Bernard played. It took several years for his next of kin to be contacted for probate purposes.

One of Desford’s Leicestershire League players was C Mandley, more likely to by Cyril Ernest (born 1923) than his slightly older brother Charles Albert (born 1922). They were the second and third children of a large family from Northampton.

Cyril seemed to get into minor trouble at various times of his life. By 1939, he would have left Desford, but was now in another Approved School in Norfolk. After the war he settled down, fathering two daughters (I can’t find a marriage record, though). In 1947 he was fined for speeding, and in 1951 he was found guilty of stealing some scrap metal.

Reading some of these stories, you wonder whether Sydney Gimson’s frequent claim of a 90% success rate stood up. You might also have increased sympathy with his view that boys should have continued to stay at Desford until 16 rather than 15: that extra year, he thought, was all-important and he may well have been right. Although some of the Desford chess players eventually made good, we see a frequent pattern of re-offending, marital problems and mental health issues, and several premature deaths. While I’m all in favour of treating young people with kindness, perhaps today we might take a more nuanced approach.

If I travelled down the road to Feltham Young Offenders’ Centre, for example (it was Feltham Borstal when my father was an instructor there back in 1950, so we’re talking about more serious offenders) I’m sure I’d find young men from difficult family backgrounds, just as Cecil Lane and Sydney Gimson did at Desford. But I’d also find young men who might be diagnosed with learning difficulties or with conditions such as ADHD. I’d find young men who had problems with drink and drugs. Everyone is different and needs a different type of support. I’ve been thinking for years I should contact them to ask if they had any interest in chess.

But I have two more Desford stories to tell.

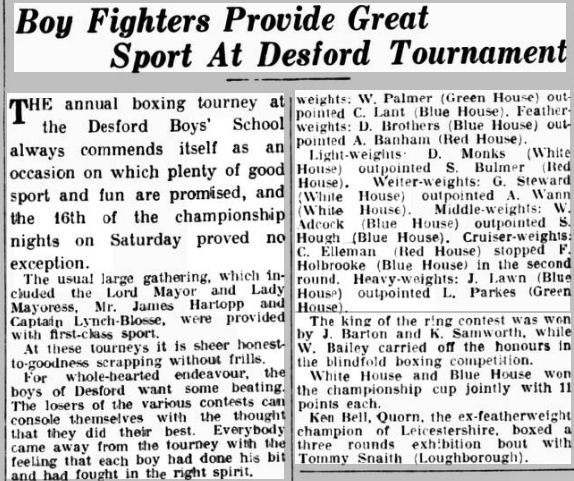

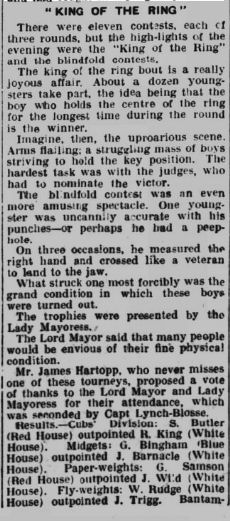

This report of the 1936 boxing tournament gives you some idea of how popular this annual event was in Leicester life at the time.

Look in particular at the cruiserweight result. Charles Elliman and Frederick Holbrooke. Charlie and Fred to their friends. Big boys for their age as well.

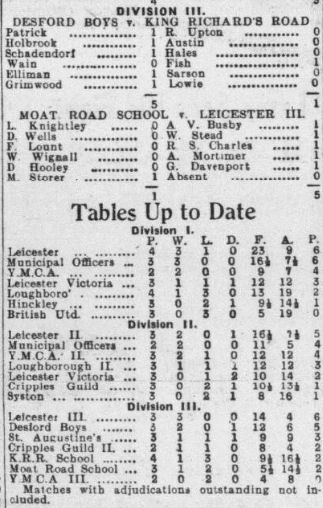

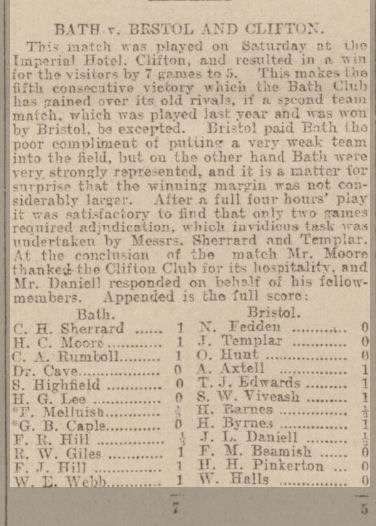

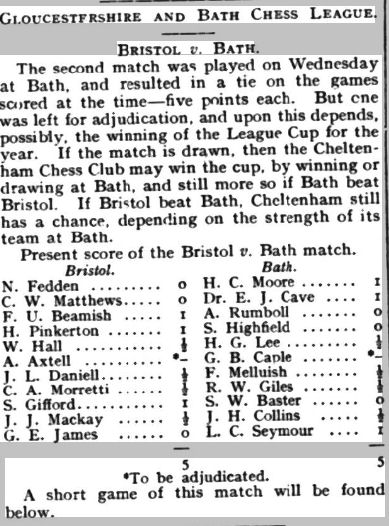

They were both chess players as well as boxers. While Charles was, at least on this occasion, the better boxer, Frederick was probably the better chess player. At the same time of year both boys were playing in the junior section of the Leicestershire Boys Championship. Frederick reached the final play-off before losing to Eric Patrick, while Charles was eliminated at an earlier stage.

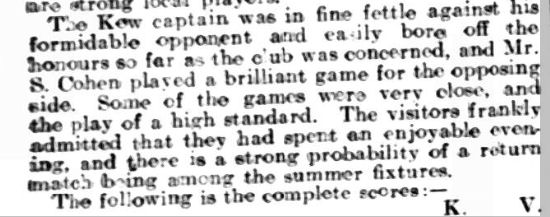

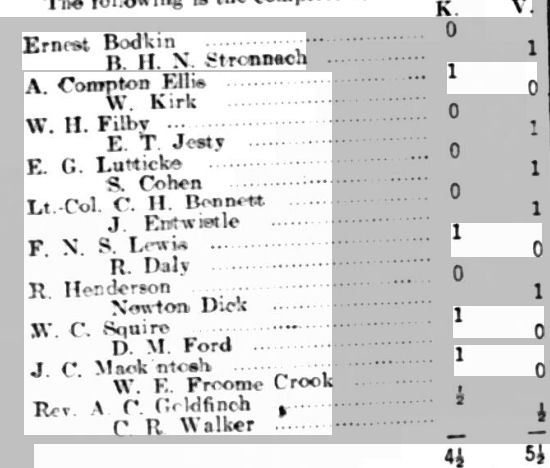

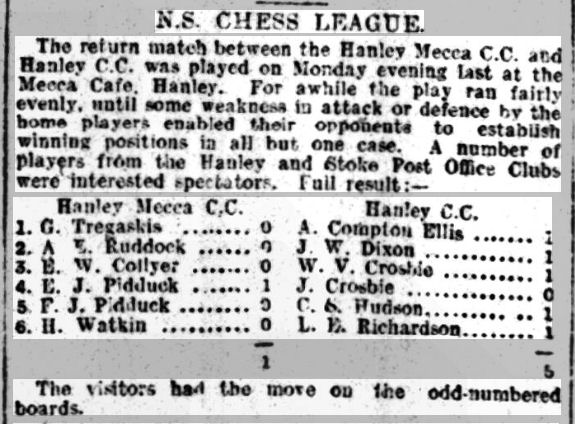

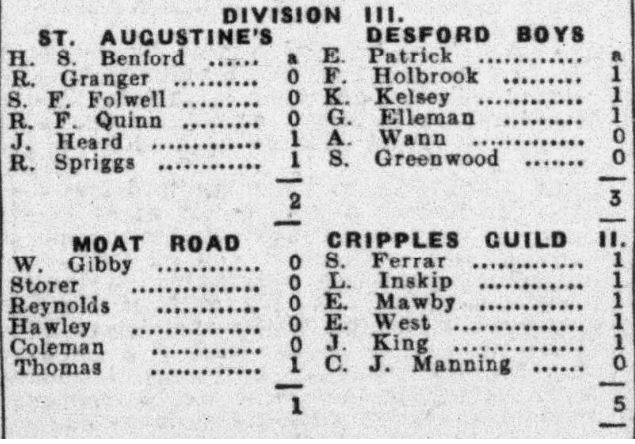

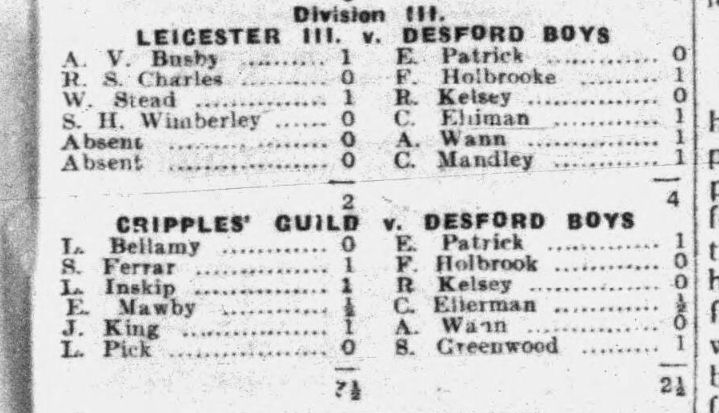

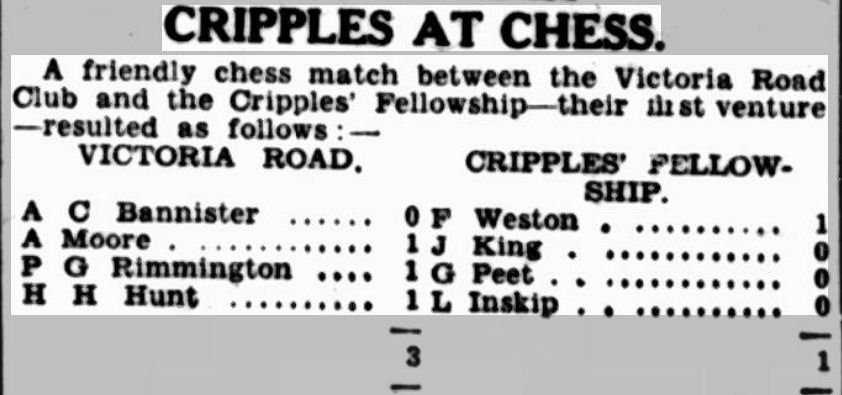

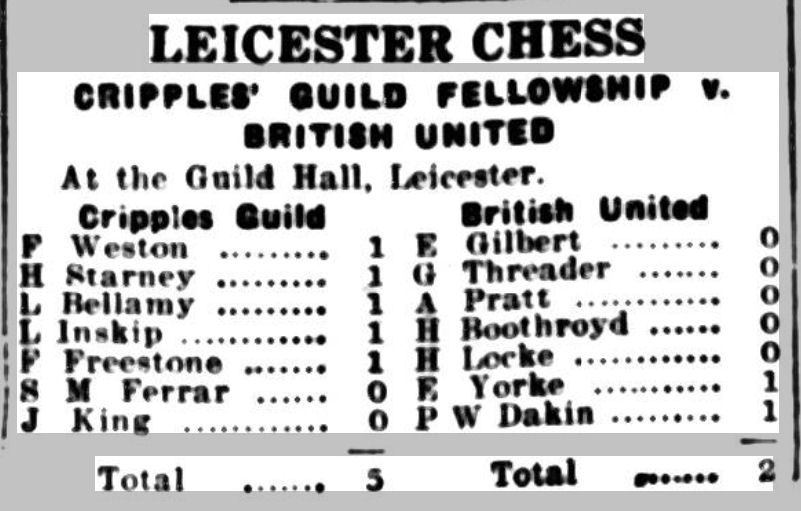

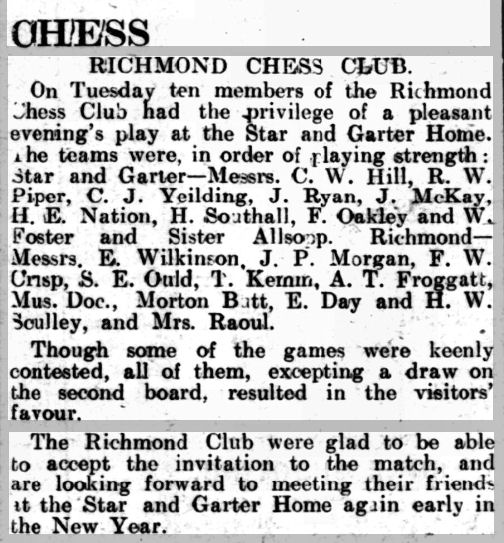

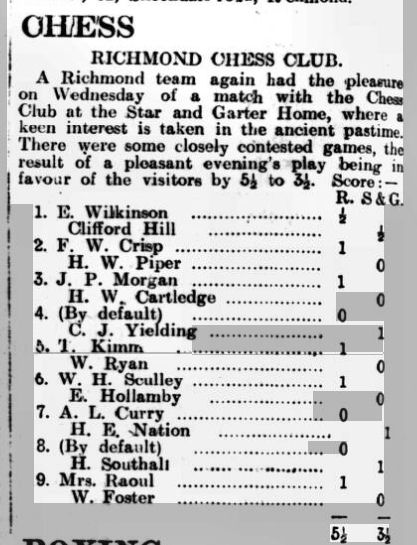

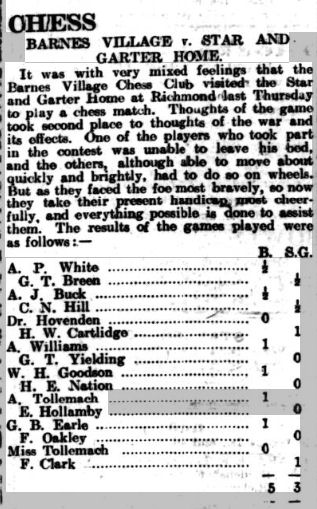

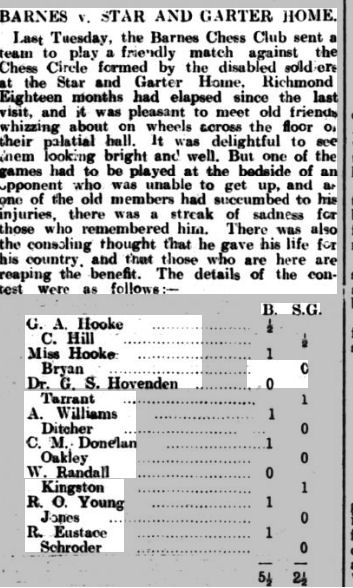

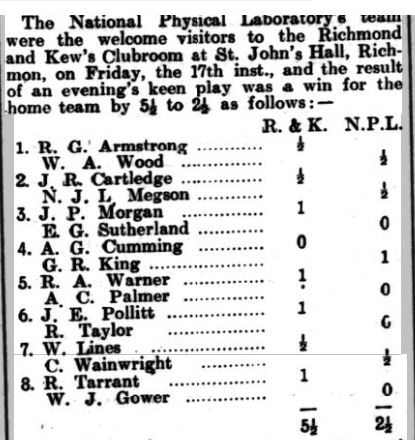

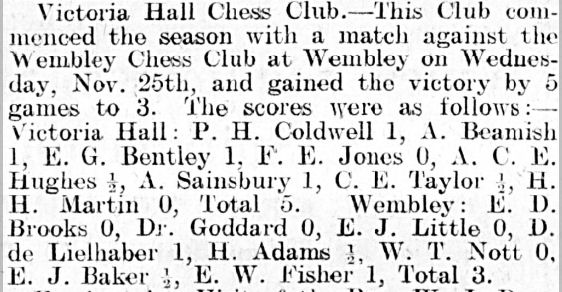

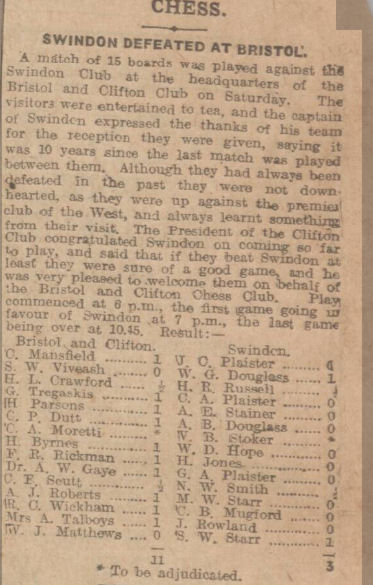

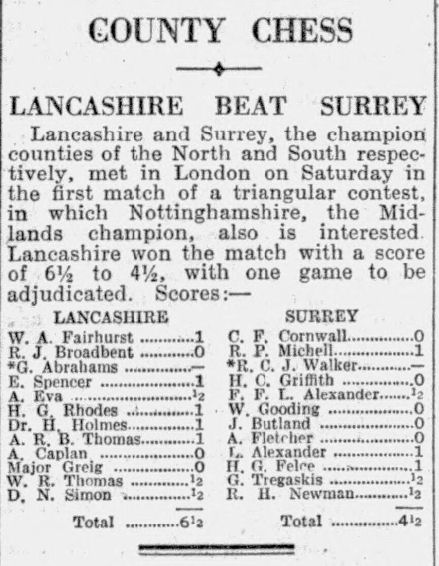

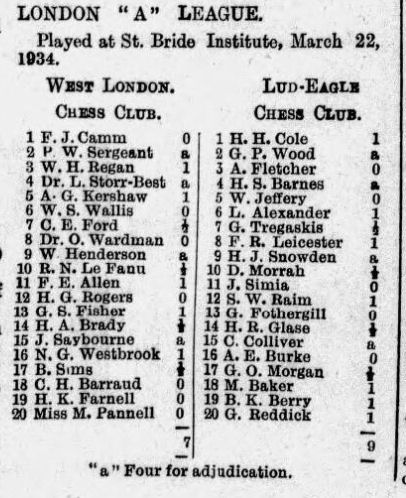

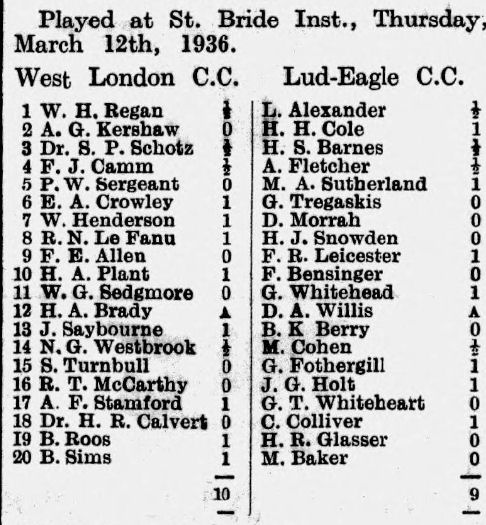

They were teammates as well as rivals over the chessboard: they were both successful, as was Richard Kelsey, in this match. (Misspellings were very common in this context – misreading handwriting I guess.)

Both boys also excelled at other sports. In the schools athletics championship that summer term, Frederick was second in the long jump while Charles was second in the 440 yards. In the schools swimming competition the previous September, Charles and Frederick had finished 2nd and 3rd behind Alan Wann in the Junior Speed Race, helping Desford to win the Ansell Trophy (any relation to Sydney Ansell Gimson?) for the third year in succession.

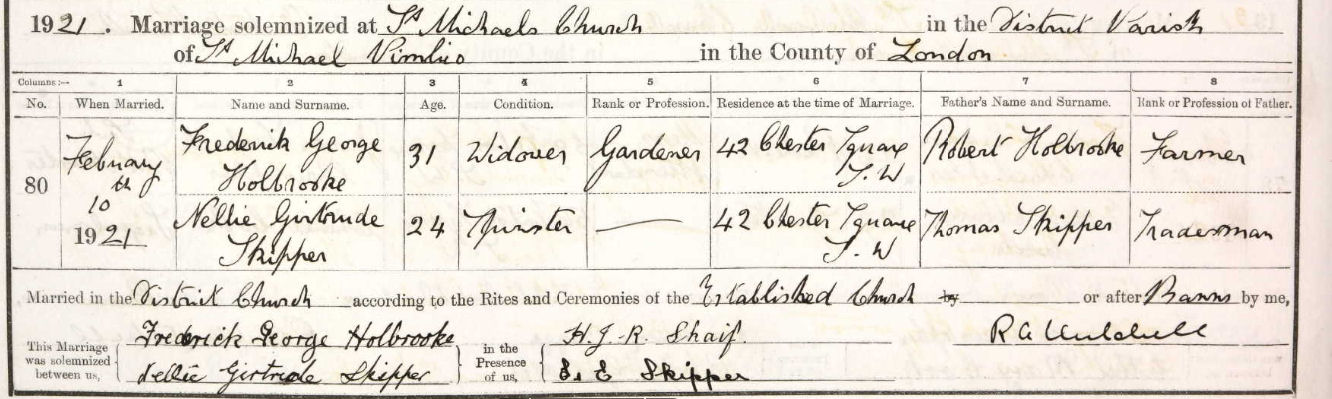

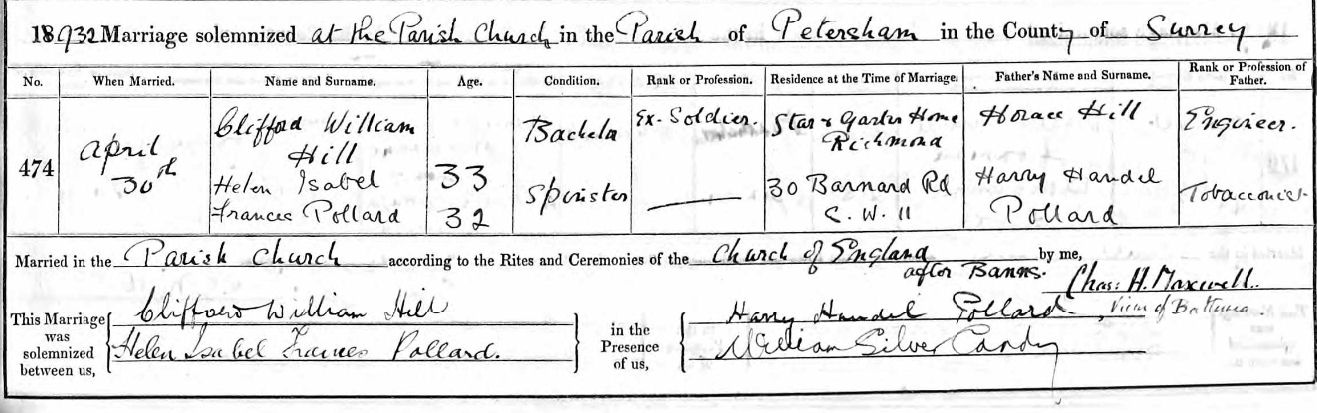

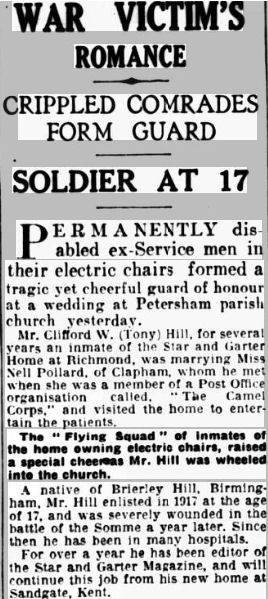

To find out who Frederick Henderson Robert Holbrooke was, let me take you to St Michael’s Church, Pimlico, in the year 1921. His name sounds rather posh, doesn’t it? And St Michael’s Church, in Belgravia, near Victoria Station, is one of London’s most exclusive areas.

Here’s a marriage certificate.

We can identify Nellie Gertrude Skipper, who came from Norfolk. However, I can find no birth record or previous marriage for Frederick George Holbrooke, nor any farmer named Robert Holbrooke.

42 Chester Terrace is presumably 42 Chester Square, immediately opposite the church, which, in 1921, was a boarding house, although there was only one boarder there in that year’s census.

It seems highly likely to me that Frederick George Holbrooke was not his real name. Perhaps, given his son’s name, he was really Henderson. Who knows? Nellie, already the mother of an illegitimate son, returned to Norfolk where Frederick junior was born a few months – or perhaps even weeks – later. Frederick senior disappeared from view until the first quarter of 1963, when his death was recorded in North East Surrey: he was buried in Merton.

Over the next two decades Nellie had several other relationships and several other children, so here, again, was a boy from a highly dysfunctional family. Again, it’s of interest that someone from that background could become a good chess player.

He would probably have left Desford in Summer 1936, and two years later he enlisted in the Royal Artillery, serving as a gunner. The following year, my father would also enlist in the Royal Artillery, seeing service in North Africa, Italy and Germany. Frederick, unlike my father, was unlucky. Killed in action in Tunisia on 3 March 1943, the reports said. He is remembered on the Medjez-el-Bab Memorial in Tunisia, and also on the War Memorial in the Norfolk village of Marsham.

Finally, we have Frederick’s friend, Charles Elleman. Charles was from Birmingham, the 6th of 15 children. The 1921 census records their mother at home with 5 children (Charles would arrive later that year) while their father was in Warwick serving with the Warwickshire Yeomanry Defence Force. In 1933, one of his older brothers was sent to prison after a series of thefts, his father also receiving a custodial sentence for receiving stolen goods. It would have been about this time that Charles was admitted to Desford Approved School.

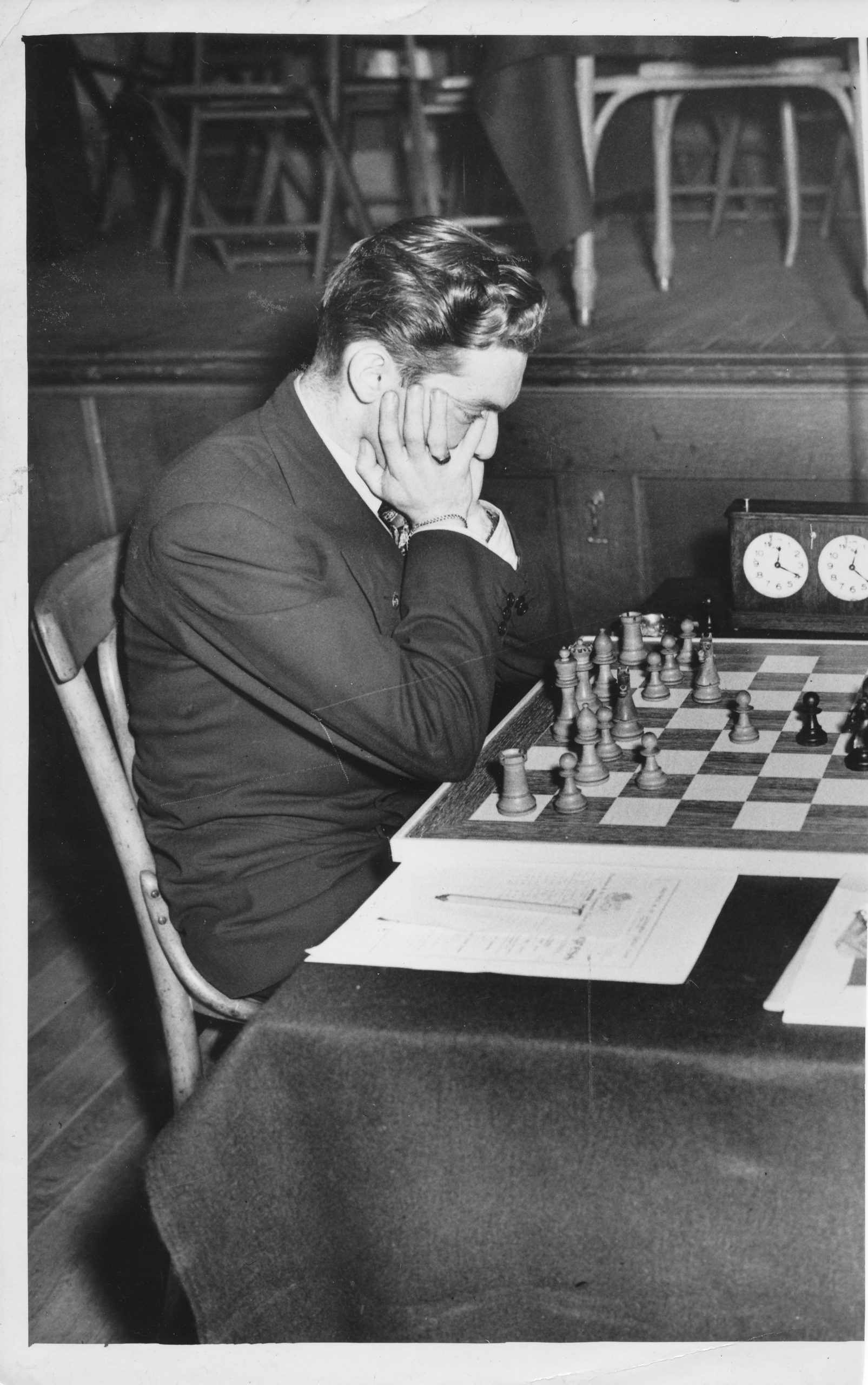

Although he wasn’t one of their strongest chess players, he took part in competitions and, in the 1936 prizegiving, won the Victor Ludorum trophy for his sporting successes. He also won the prize for the most public spirited boy in the school. Here he is, on the left, being chaired by his fellow pupils.

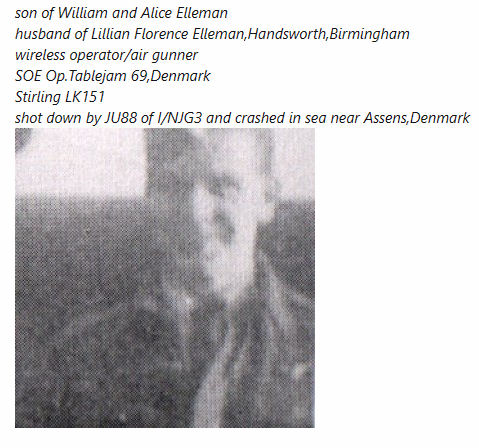

At this point Charles, like Frederick, would have left Desford to seek employment. The 1939 Register found him working as a waiter at the Grosvenor Hotel in Heysham, Morecambe. But, like the public spirited young man he was, he chose to serve his country when war was declared. It wasn’t the Army or the Navy for him, but the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve.

He returned to Birmingham in 1942 to marry Lillian Florence Hands, in a break from his job as a wireless operator in 138 Squadron Bomber Command. On 27 November 1944 his Stirling IV was shot down off the coast of Denmark, returning from dropping supplies to the Danish Resistance. Pilot Officer Charles Elleman died as he had lived his life in Desford Approved School, a true hero. A son, Thomas C Elleman, was born in the 4th quarter of 1944: whether before or after his father’s death I don’t know: he married Betty J Astle in Bristol in 1967. There’s an Australian biochemist with a lot of patents to his name called Thomas Charles Elleman: his wife is Betty Jean, so I think this is our man. His father would have been very proud of him, and he must also be very proud of his father.

Charles’s life is commemorated on Panel 211 of the Runnymede Memorial.

Two friends, then, opponents in the boxing ring and on the sports field, both opponents and teammates over the chessboard. Two friends who both lost their lives serving their country and the free world.

In the words of AE Housman:

They carry back bright to the coiner the mintage of man,

The lads that will die in their glory and never be old.

These lines of Lord Dunsany also come to mind (British Chess Magazine April 1943).

One art they say is of no use;

The mellow evenings spent at chess,

The thrill, the triumph, and the truce

To every care, are valueless.

And yet, if all whose hopes were set

On harming man played chess instead,

We should have cities standing yet

Which now are dust upon the dead.

Let’s drink a toast, then, to Desford war heroes Frederick Holbrooke and Charles Elleman. To poor Eric Patrick and Bernard Tedman, who ended their lives in mental hospitals. To Victor Duffin and Hubert Cookland, who, after difficult starts, found success and happiness, leaving behind fond memories for their children and grandchildren. To all the other Desford chess players as well. And let’s not forget the two men who made it possible, Cecil Lane and Sydney Gimson.

For those of us involved in junior chess administration, are there lessons we can learn here about the true purpose of chess at secondary school age? Apart from their strongest player, Eric Patrick, who continued for another year, none of them seemed to play any more competitive chess (although Victor was a competitive dominoes player). But perhaps that’s not really the point. Perhaps it brought some happiness to young people who had had a troubled start in life, and you shouldn’t expect any more than that.

If you were hoping to see some chess moves in this article, I can only apologise. I’ll introduce you to some Leicester chess players with longer careers in future Minor Pieces.

Acknowledgements and sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archive

Wikipedia

YouTube

Bethlem Museum of the Mind website

Special Forces Roll of Honour website

Other sources linked to or mentioned above

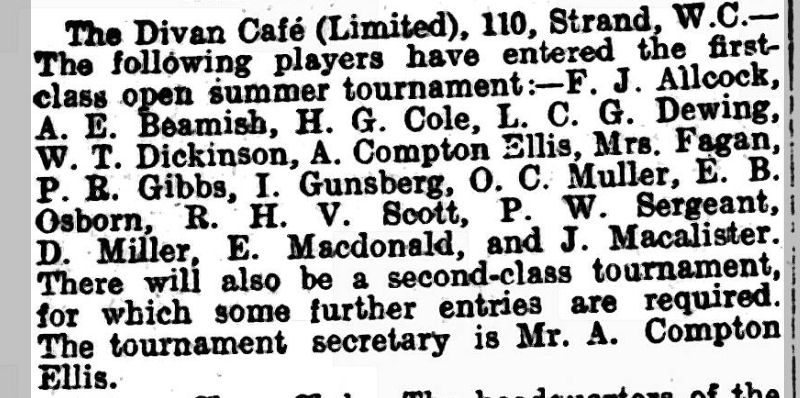

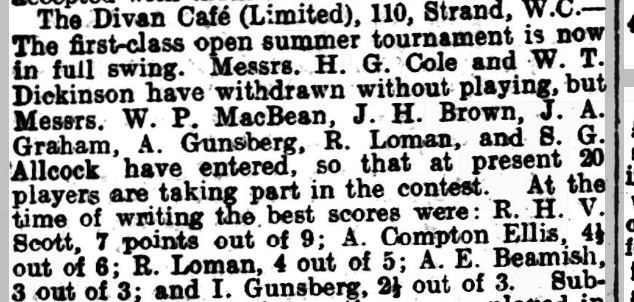

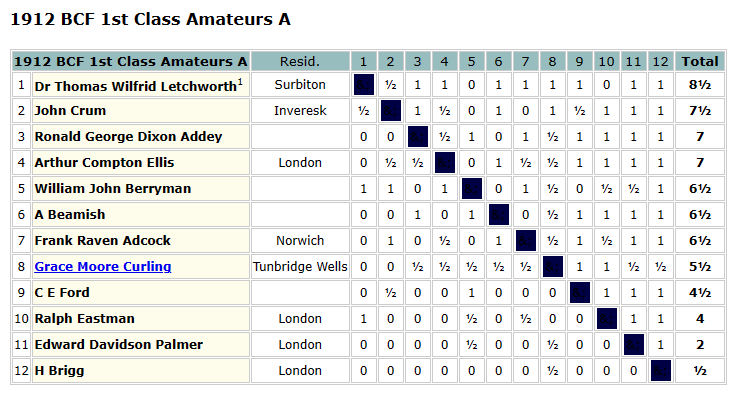

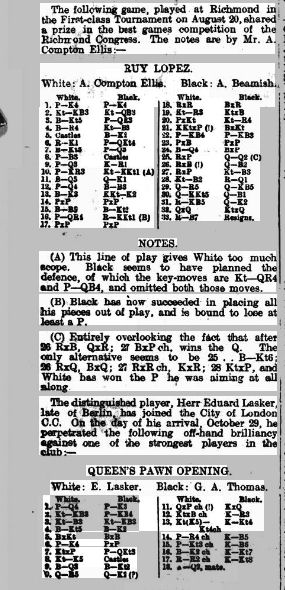

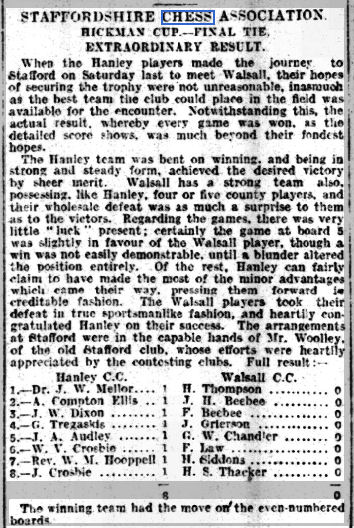

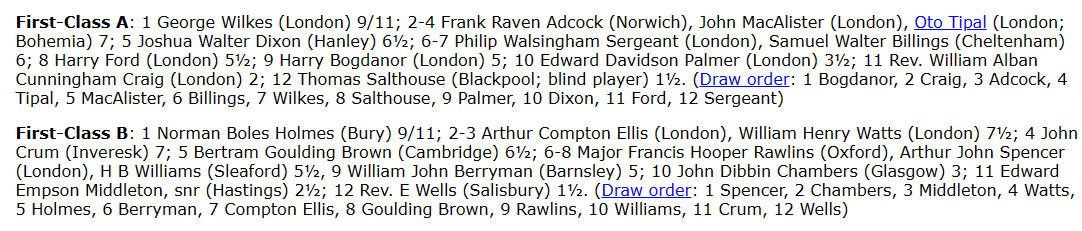

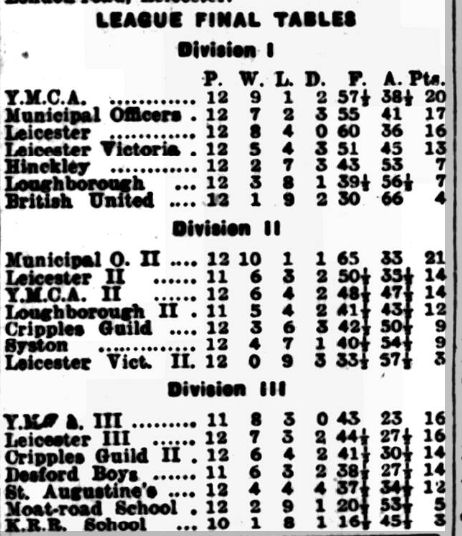

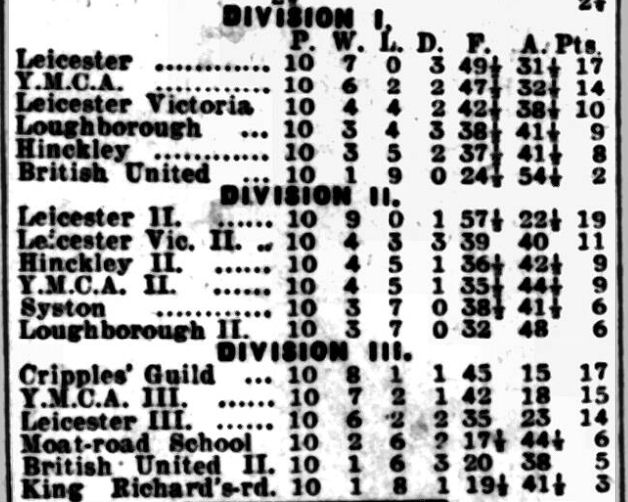

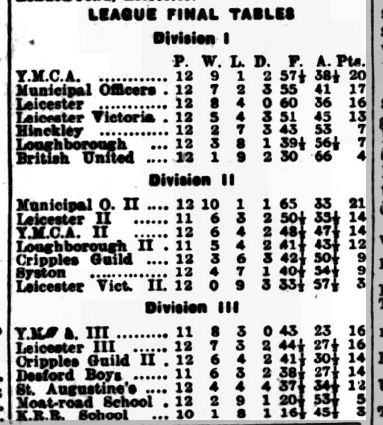

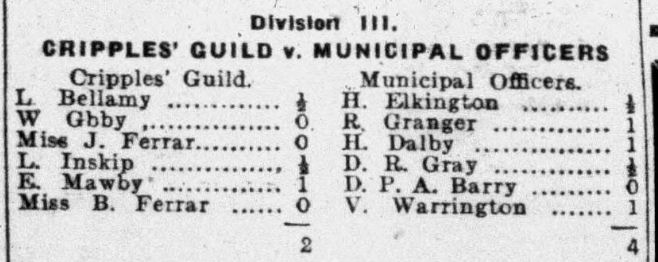

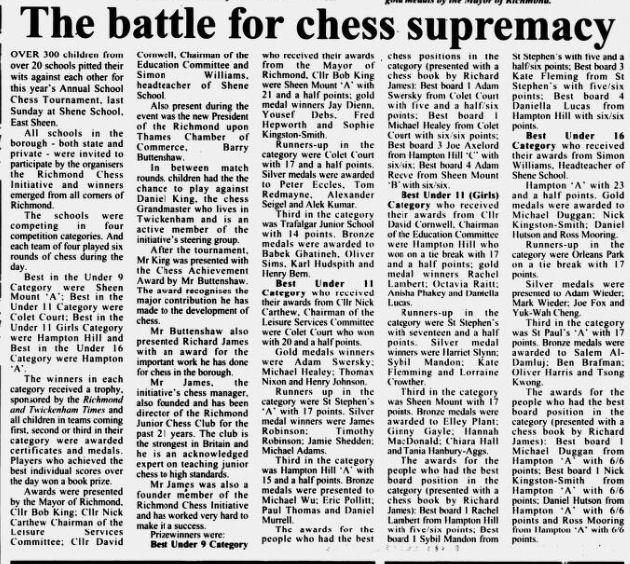

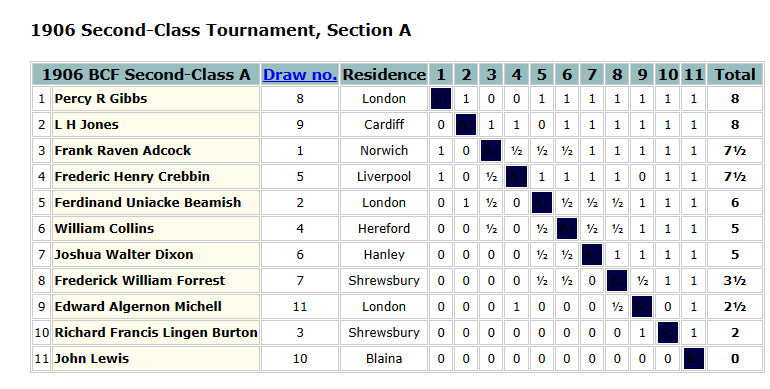

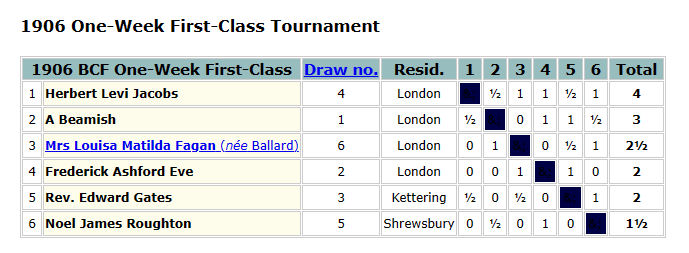

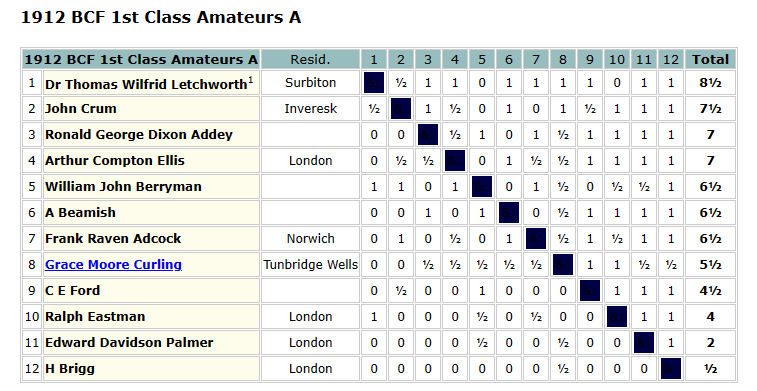

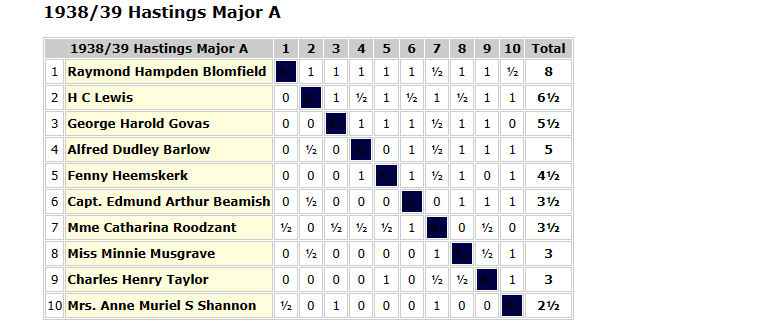

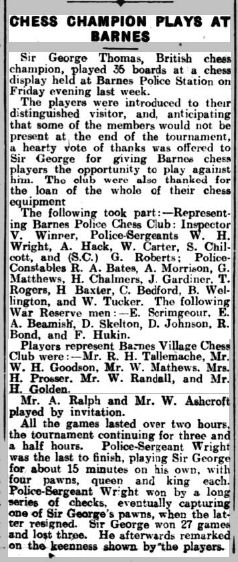

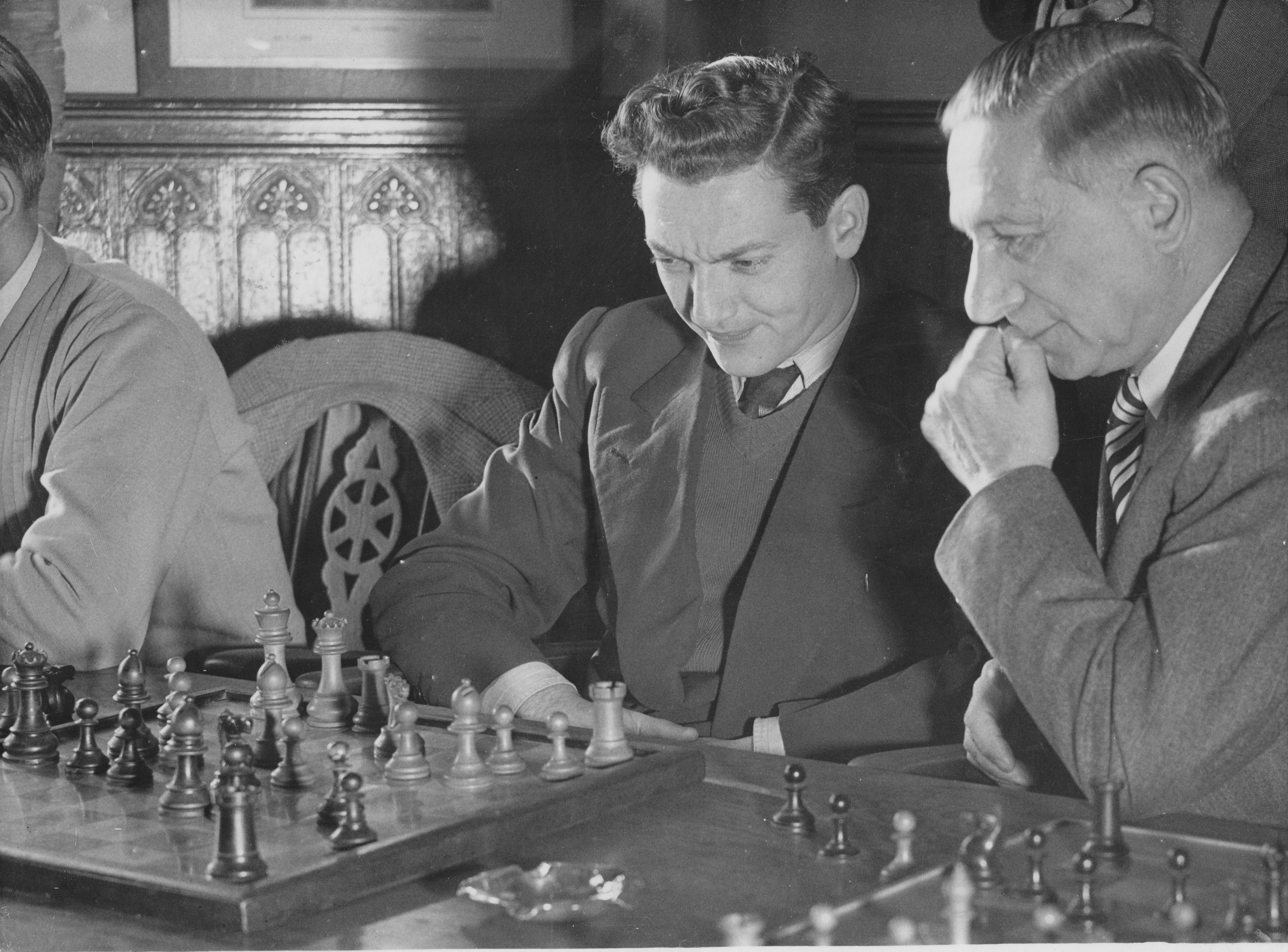

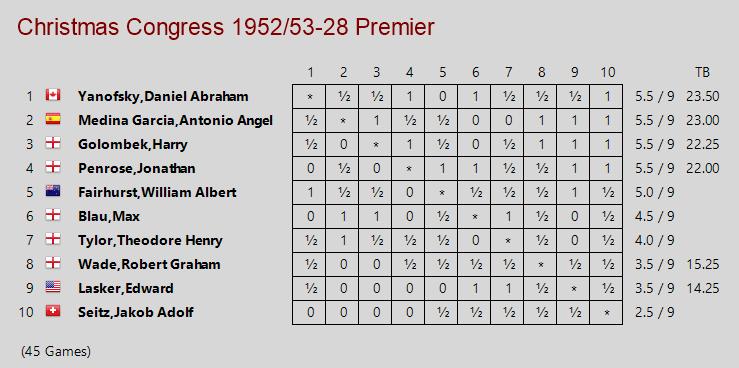

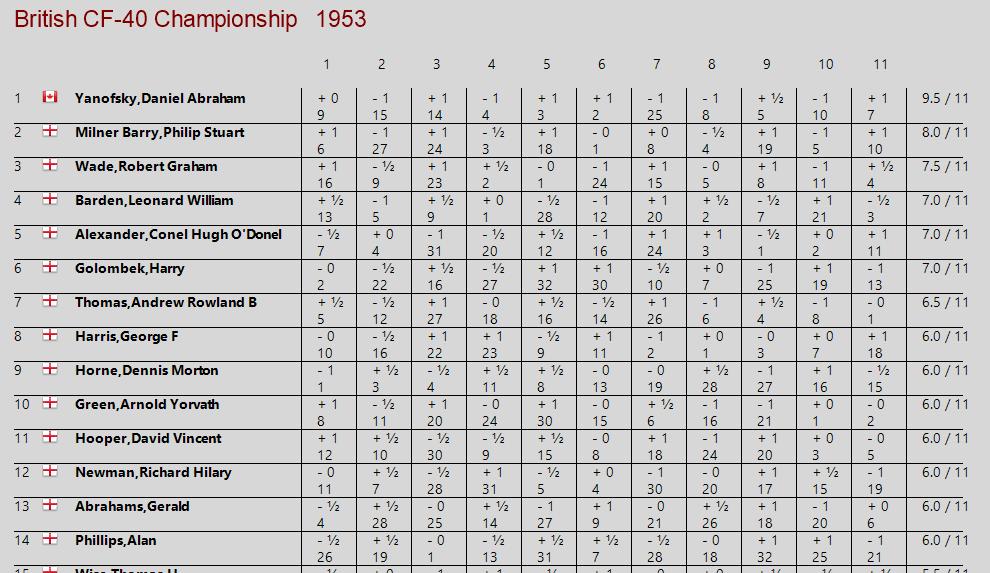

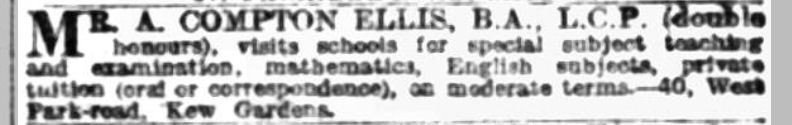

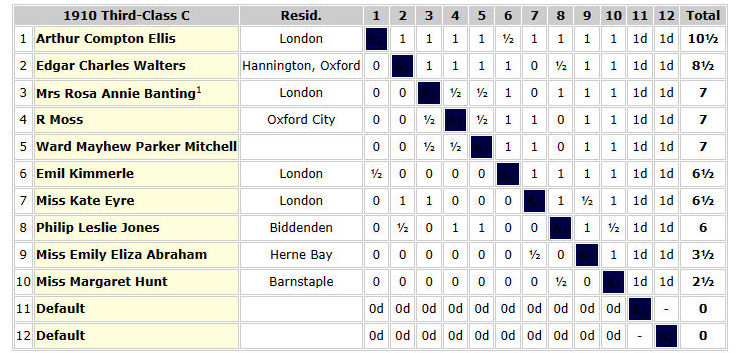

With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than

With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than