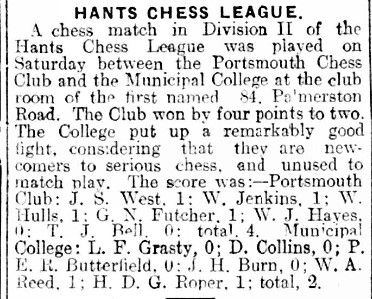

If you read anything about chess from the late 1880s through to 1909 you’ll often come across the name of FJ (Francis Joseph) Lee, a regular competitor in both national and international events during that period. He played pretty consistently at about 2350 strength, finishing below the genuine masters, but above the amateurs. Yet he had wins against the likes of Steinitz, Pillsbury, Chigorin, Blackburne, Mason and Atkins to his credit.

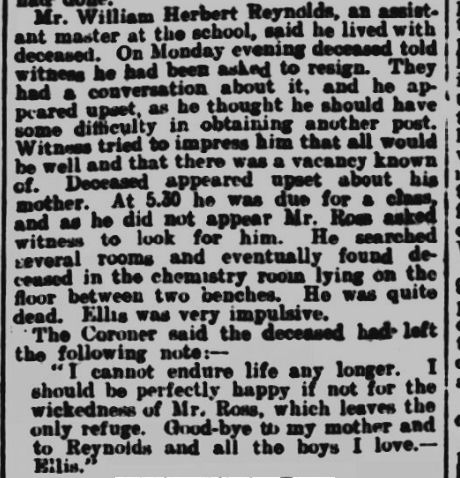

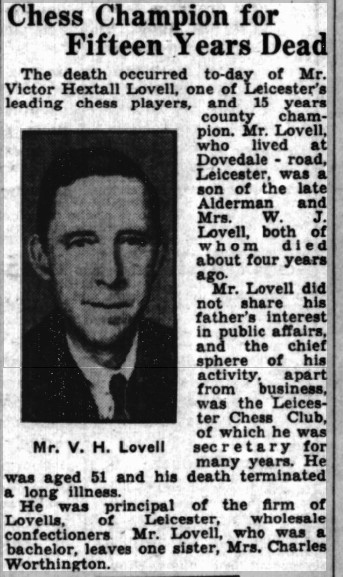

Here he is, pictured, I think, in 1893.

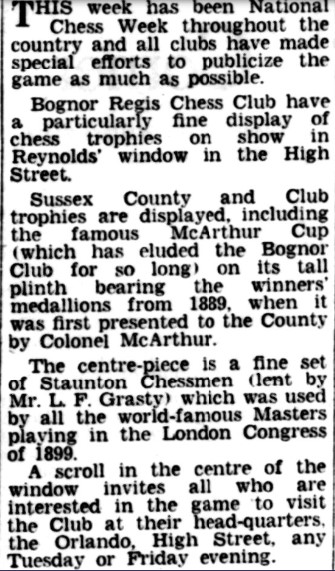

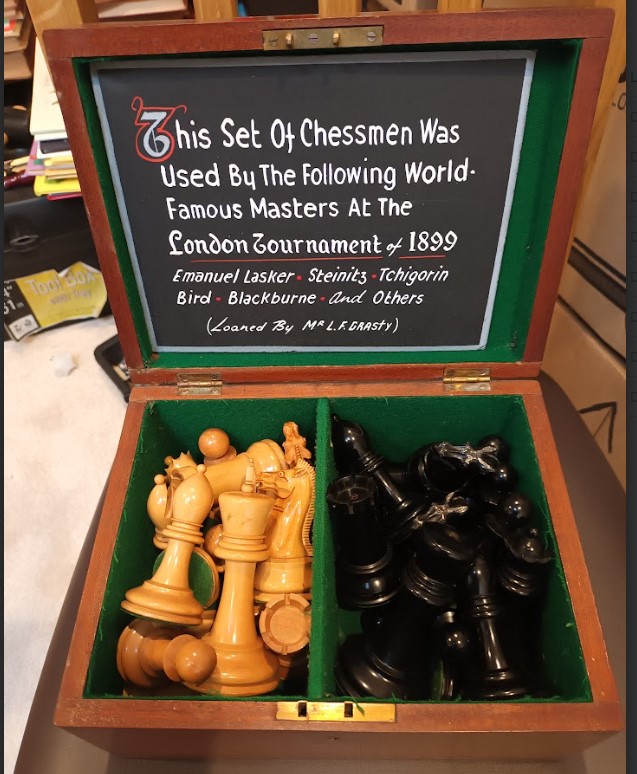

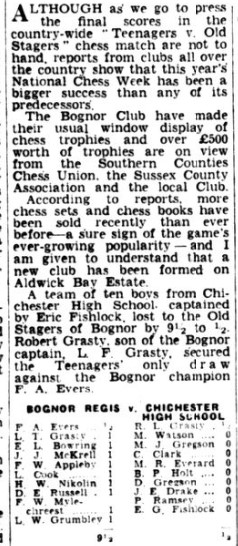

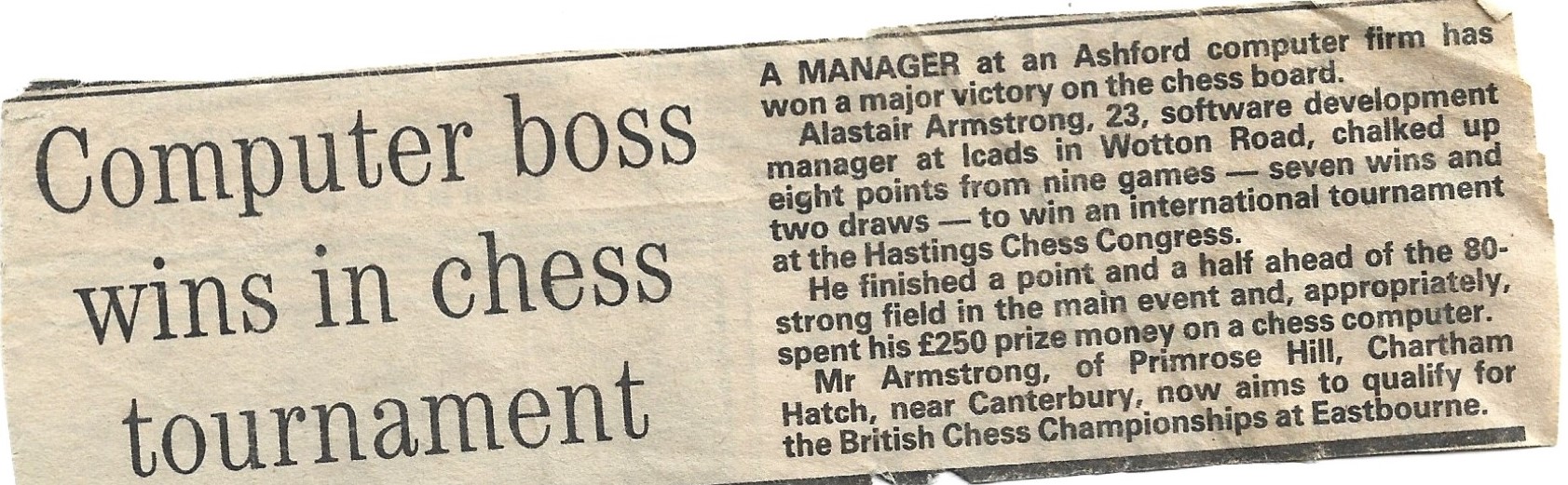

A decent player, to be sure, but I’ve seen very little written about him. As he might have used my friend Alastair Armstrong’s chess set when taking part in the 1899 London International Congress, I wanted to discover more about his life and games.

Francis Joseph Lee’s birth was registered in the first quarter of 1858 in Hackney. He was baptised at St Matthias Church, Stoke Newington, on 28 April that year. His father, Francis Goodale Lee’s profession was given as architect: as far as I can tell he was a minor church architect. He was also, although he didn’t play publicly, an enthusiastic chess player. His mother, more exotically, was Rosina Pereira Arnand, the daughter of a wine merchant, about whom I can find out very little. Pereira is a Portuguese name, and Arnand sounds French (perhaps it’s a version of Armand, which really is a French name). Many years later, Francis would tell how he was romantically affected by her tales, and also inherited her musical tastes. He had an older sister, Agnes, and two younger brothers, George and Arthur.

There’s no obvious trace of the family in the 1861 census, but in 1871 Francis and his brother George were recorded at Belmont House, Ramsgate, a boarding school for young gentlemen.

At this point we should perhaps mention a couple of other things. In 1874 a 16 year old named Francis Joseph Lee signed up for four years in the Merchant Navy. In an interview many years later he mentioned going to sea and visiting China, so I’d guess this was him. In 1885 a Francis Joseph Lee married Kat(i)e Elizabeth Jenner in Hackney, divorcing a few years later, but we can tell from the church records that this wasn’t our man – both his age and his father’s name were wrong.

By 1881 Lee was boarding in Hackney and working as a stockbroker’s clerk. He may have been playing chess at Purssell’s room by then, but the first time his name appeared in the press was in 1885 at Simpson’s Divan, losing a game against William Henry Krause Pollock, who gave odds of pawn and move. It must be round about this time that he decided the life of a stockbroker’s clerk was not for him, opting instead for the life of a chess professional. He wasn’t a strong enough player to make much money from tournament play.

He was a relatively late starter at this level, then, and, judging from this 1886 game he favoured the gambit style popular at the time.

As usual, click on any move on any game in this article for a pop-up window.

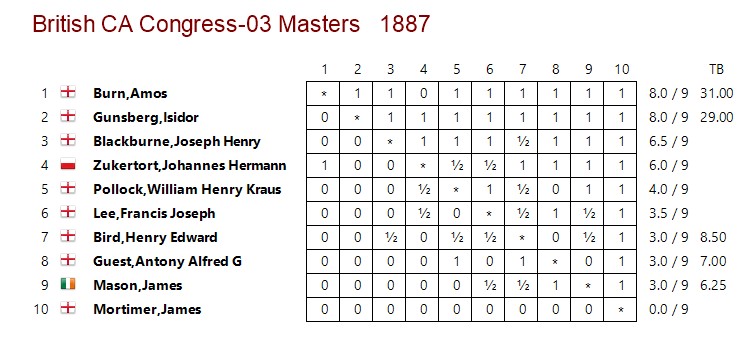

The following year he beat Pollock 6-1 in an odds match, establishing himself, almost from nowhere, as one of the country’s leading players, and earning an invitation to take part in the 3rd British Chess Association Congress Master Tournament in London in November.

A respectable performance, but it should be pointed out that Zukertort, coming to the end of his life, was in poor health, as, no doubt, was Mason.

Lee won a nice ending against chess journalist Antony Guest.

Here’s a position from his game against Zukertort.

In this position he missed the rather attractive 23… Rd3!, which would have won Zukertort’s queen (if the queen moves to safety there’s Qxh2+!): perhaps his tendency to make tactical errors led him to follow the increasingly popular trend for closed positions, already in evidence in this tournament.

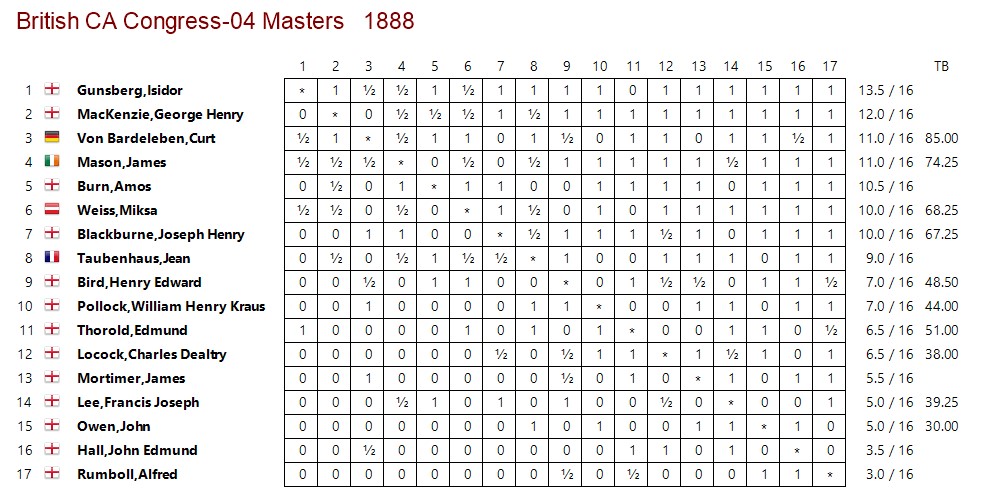

The following year, the British Chess Association Congress took place outside London for the first time, being held in Bradford. It was a pretty strong event as well, as you’ll see.

Lee’s result was slightly disappointing, but he did have the satisfaction of beating Burn and Blackburne.

Blackburne seemed ill at ease against Lee’s French Defence, and Black was able to liquidate into a winning ending.

Burn was also outplayed from a closed position.

In January 1889 Lee played a short match against Gunsberg, drawing two and losing three of the five games.

The 1889 British Chess Association Congress returned to London in 1889, with Bird and Gunsberg sharing first place on 7½/10, two points ahead of the field. Lee finished in the middle on 5/10. Very few games from this event seem to have survived.

We do have this one, though, where White moved his king to the wrong square on move 34.

1890 was a busy year for Lee. He scored his greatest success to date in the spring handicap tournament at Simpson’s Divan, with a score of 16½/18, well ahead of the likes of Bird, Tinsley and Mason.

This game against a Russian master demonstrates how effective he could be with the French Defence.

He spent much of the summer involved in a match against Blackburne, which he lost 5½-8½.

Here’s one of his wins.

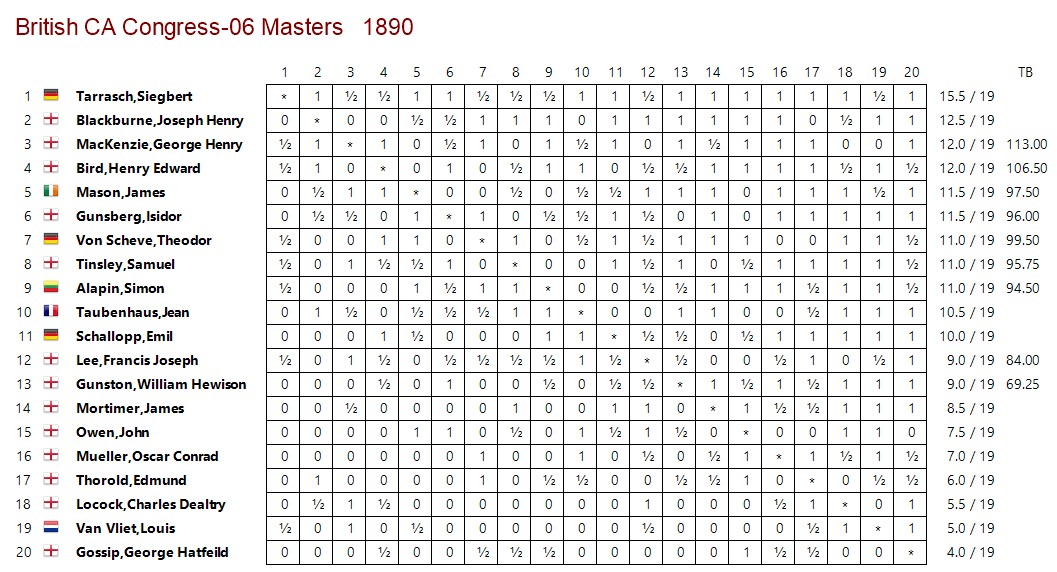

Following on from that match he travelled to Manchester, where the 6th British Chess Association Congress took place. This attracted a strong field of 20 players, including Tarrasch, arguably the world’s best player at the time.

Lee’s result was again respectable, finishing about as expected, but taking points off some of the stronger players, while faring less well against some of the weaker players.

I haven’t been able to find the scores of any of his wins from this event, although he certainly should have won with the black pieces against von Scheve.

In this position, instead of playing 38. Bxb7 (equal according to Stockfish), von Scheve tried Rxb7?, presumably thinking he was either promoting or mating, but he must have missed something. Undaunted, he played on a piece down in the ending, eventually reaching this position, with Lee to play.

Now 62… Rh2+ is mate in 7, but Lee fell for a stalemate trap by playing 62… Rg2? 63. Ra5+ Kf4 64. Rf5+! with a draw. A familiar enough idea now, but it would have been much less familiar back in 1890.

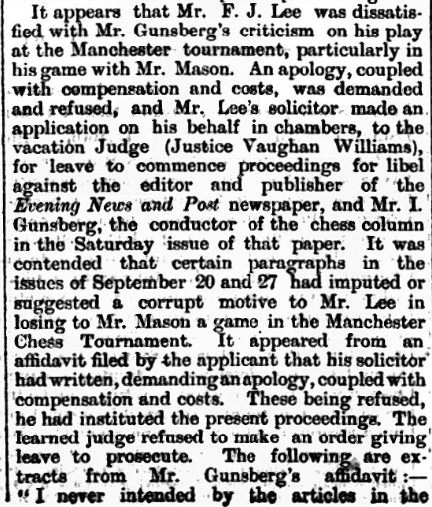

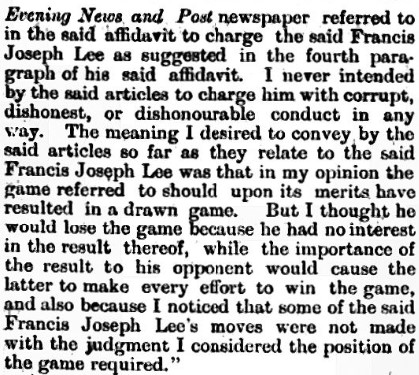

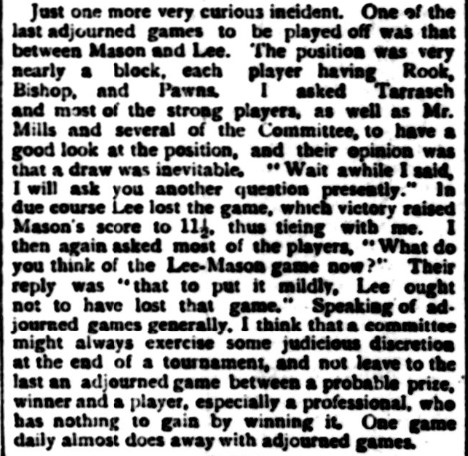

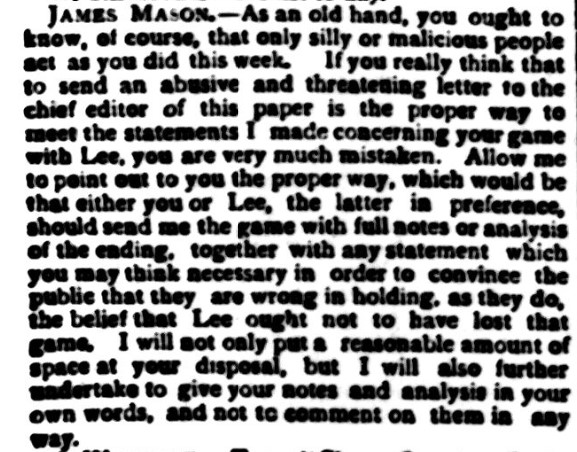

Lee was unhappy with Gunsberg’s annotations of his loss against Mason from this tournament, and attempted to sue him for libel, but the judge (Roland Vaughan Williams, whose nephew, the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, is one of my musical heroes) refused to allow a prosecution

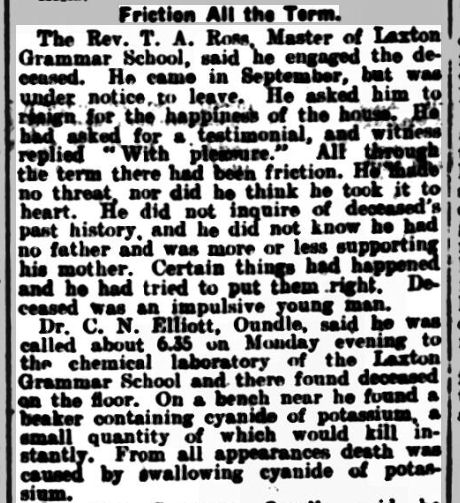

Here’s the paragraph from 20 September:

Both Mason and Lee were unhappy with this, Mason writing to the editor of the newspaper.

You can judge for yourself: here’s the critical position after a lot of rather tedious manoeuvring, with Lee (Black) to play his 71st move.

Stockfish suggests 71… Rc1 72. Kd4 Rd1+ 73. Kc3 Kb7, pointing out that 73… Bxc4, for instance, is also a draw. Lee preferred 71… Bxc4? 72. Rxc4 Rf1? (another poor move: Re1+ might have offered some drawing chances) 73. Rc6+, when Mason obtained two passed pawns, soon winning the game.

What do you think? Was Lee tired after a long game and a long tournament? Was the position too hard for him? Was he not trying too hard as there was nothing at stake for him, as Gunsberg thought, or did he deliberately throw the game, as he thought Gunsberg implied?

At the same time, Lee was branching out as a writer, taking over the regular chess column in the Hereford Times in September 1890.

In between tournaments he was travelling throughout the British Isles giving simultaneous displays, often being billed as The Young Master.

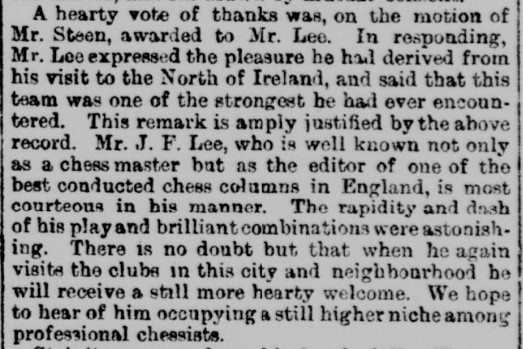

Here he is in Belfast in December 1890, feted for his courteous manner as well as his rapid and brilliant play. He had also, in September that year, taken over the chess column in the Hereford Times, which he continued until 1893.

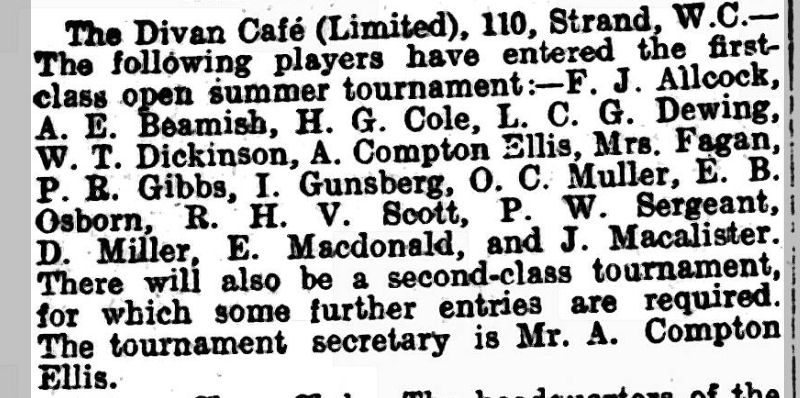

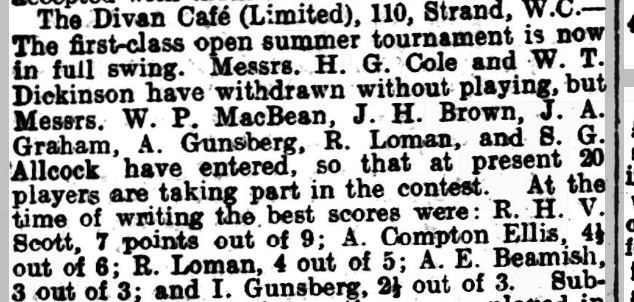

1891 was a quiet year, with no British Chess Association congress for him to take part in. There was a summer tournament at Simpson’s Divan, where he performed disappointingly, finishing in 9th place out of 10. The London based Dutch players Loman and van Vliet took the first two prizes. In August he arranged a match against up and coming German star Emanuel Lasker, drawing the first game, but, with the second game adjourned (Lasker was winning) was obliged to concede the match due to ill health. This may well have been the reason for his poor performance in the earlier tournament.

In the 1891 census he was lodging at 30 Manchester Street (now Argyle Street), St Pancras, giving his occupation as Chess Player and Editor (the word Author was added in) and his place of birth, curiously, as Ingatestone, Essex.

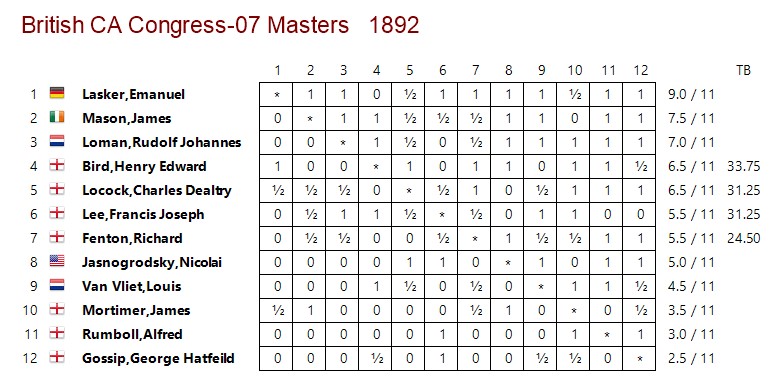

The 1892 edition of the British Chess Association Congress took place in London in March, with Lasker taking part, and, as expected, finishing comfortably ahead of the field. Lee’s 50% score was about what he would have expected.

Here’s his loss against Lasker, who sacrificed some pawns to get to his opponent’s king.

His win against Bird was a lively affair which won the brilliancy prize.

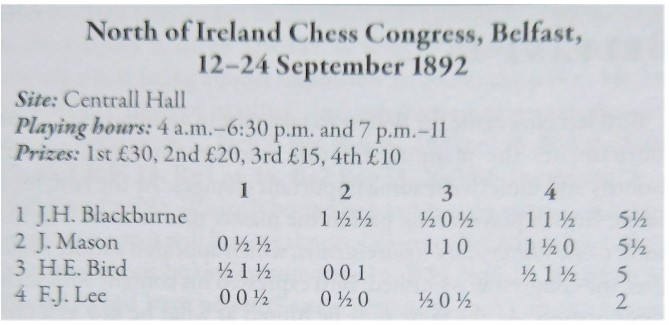

Next stop was Belfast, for a quadrangular tournament in which he was rather off form, finishing well behind his three rivals. According to a contemporary report he was unwell throughout the event. (One of the games, a featureless draw between Bird and Lee, is missing from MegaBase, but is readily available elsewhere.)

He remained in Ireland for several months after this event, visiting clubs and giving simultaneous displays.

This game, undated in my source, against Mary Rudge, the leading lady chess player of the time, may well have been played in one of these simuls.

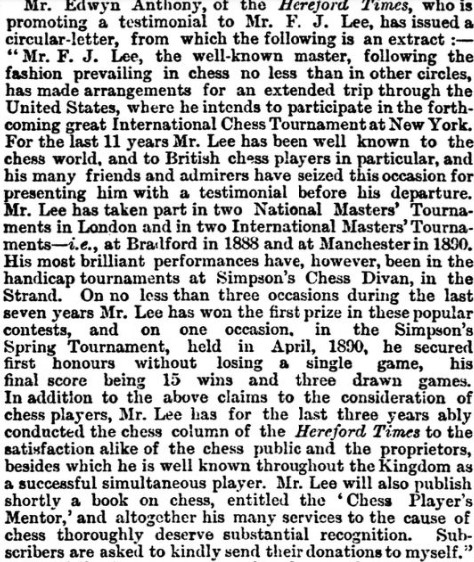

In June he had some important news to announce.

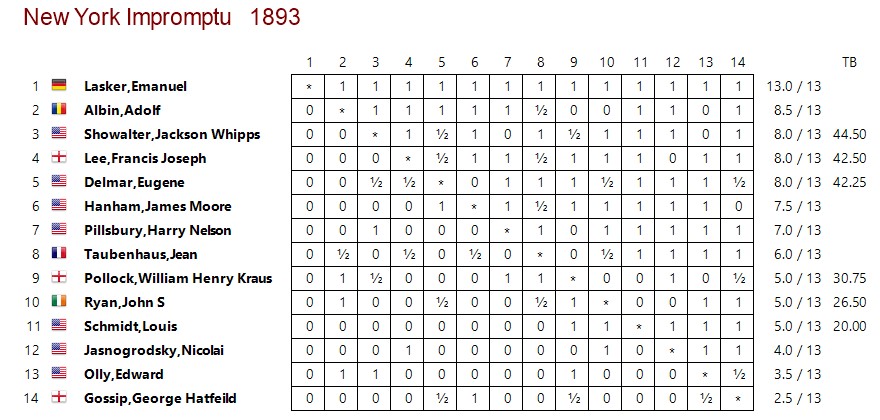

He crossed the Atlantic with his friends Gossip and Jasnogrodsky, but the intended tournament fell through. However, an impromptu tournament was organised as a partial replacement, attracting a lot of press coverage.

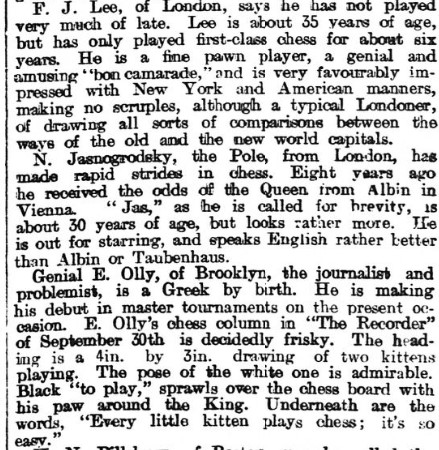

According to the Brooklyn Daily Standard Union:

The English player is about 40 years of age, of a German blocky build, which indicates the possession of physical strength to stand the strain of severe chess playing.

(He was actually 35, and I don’t think you’d get away nowadays with ‘German blocky build’, whatever that might mean.)

Reproducing the portrait (probably the one above) from the New York Sun, it added:

… makes him appear stouter than he really is; otherwise the likeness is good.

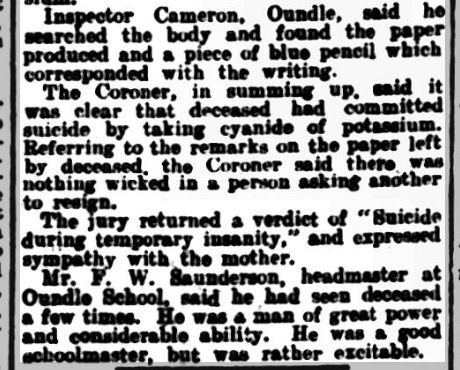

The Baltimore News provided brief and amusing descriptions of the participants, reprinted here in an English newspaper.

I think all chess columns should be headed by a picture of chess playing kittens. Don’t you?

Here, Lee performed well, sharing third place with two of the top American players, Showalter and Delmar, just behind Albin (of countergambit fame), but they were no match for Lasker, who posted a 100% score.

His Irish opponent in this game essayed the Pirc Defence long before it became popular and acquired a name.

Lee is standing fourth from the left in this group photograph from the tournament.

Lee remained in the Americas for two years after this event. In February and March he played a series of exhibition games against some of Cuba’s leading players in Havana.

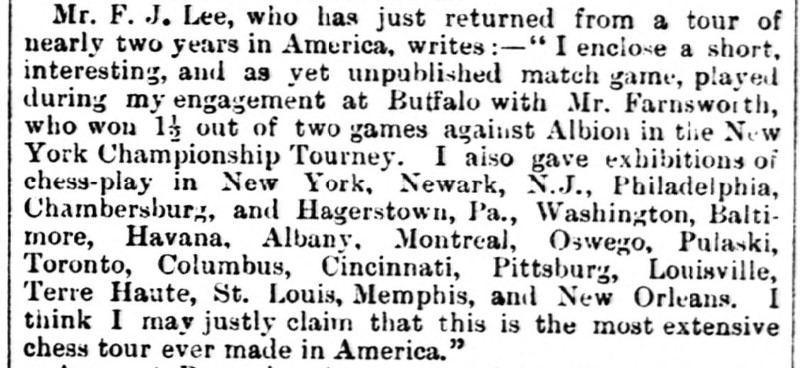

Later in the year he returned to North America, touring extensively, giving simuls and playing exhibition games.

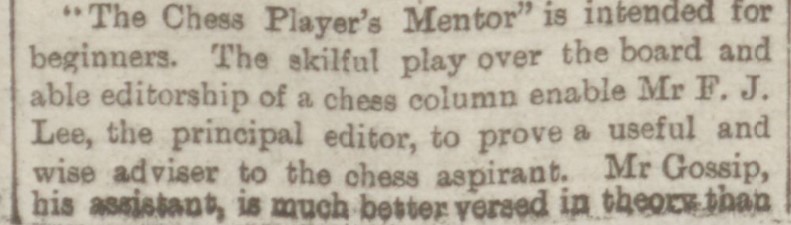

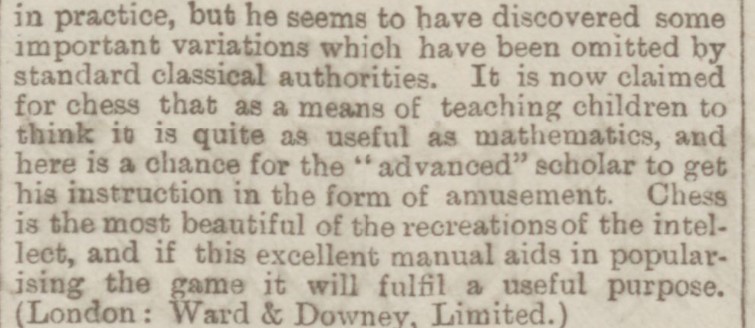

At the beginning of 1895 The Chess Player’s Mentor was finally published, offering, according to the advertisements, ‘an easy introduction for beginners’, along with ‘analyses of the most popular openings for more advanced players &c’.

The review in the Dundee Advertiser is notable for providing an early example of promoting chess for children for its claimed extrinsic benefits.

It was later republished together with three other books solely written by Gossip. You can read it online here via the Hathi Trust digital library.

Lee returned to England in July that year, but didn’t enter the great Hastings tournament. Perhaps he needed a break after his exertions.

I think it was Albin, rather than Albion, against whom real estate man George C Farnsworth (1852-1896) scored 1½/2

Here’s Lee’s win. Not all that interesting: White chose a poor 5th move and never really stood a chance.

This game shows Farnsworth in a much better light.

He spent the latter part of 1895 touring chess clubs throughout the country, but most of 1896 in London, where he was appointed secretary to the committee organising a tournament at Simpson’s Divan. His administrative role didn’t stop him achieving an excellent result, sharing second place with van Vliet on 8½/11, just half a point behind the winner, Richard Teichmann, who was based in London at the time.

Not many games from this event were published. Here, Dutch organist Rudolf Loman sacrificed a piece unsoundly.

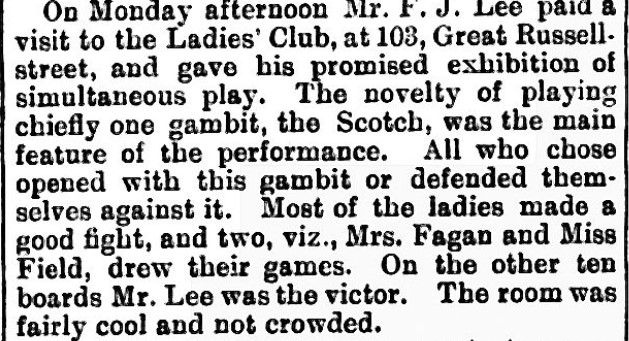

His displays in London included a visit to the Ladies’ Chess Club.

In December, Lee played a short match against Richard Falkland Fenton, winning two games, drawing two and losing one.

1897 was another quiet year spent in London, the only serious chess activity being a match during the summer against enthusiastic veteran Henry Bird, which he won by 8 points to 5.

1898 was even quieter, with just a summer match against Teichmann, which he lost 3½ to 5½. Lee suffered from gastric problems all his life: perhaps this was one reason for his relative lack of activity during this period.

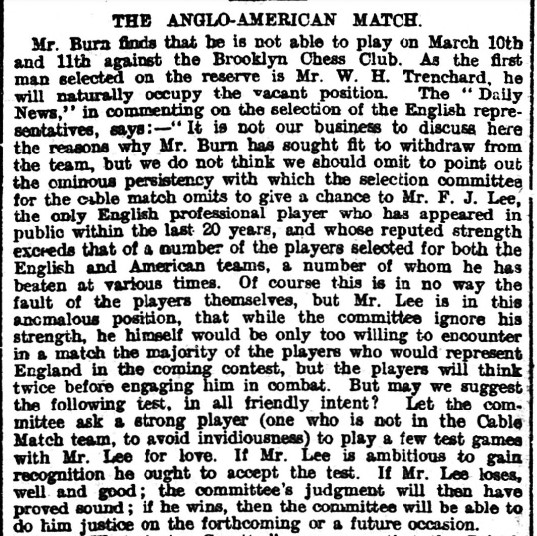

There had been some talk in 1897, and again in 1899, about why Lee wasn’t selected for the Anglo-American Cable Matches. Perhaps the selectors preferred to choose amateurs rather than professionals. Here’s an article from 1899.

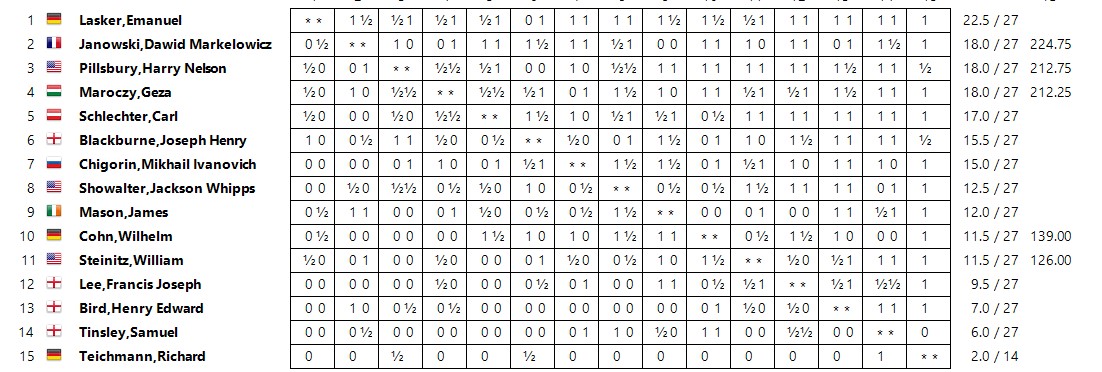

Finally, a few months later, he had an opportunity to prove himself at the top level. You will know, if you read my previous Minor Piece, about the great London International Chess Tournament of 1899. Lee was originally selected for the subsidiary single-round event, but when Horatio Caro (of Caro-Kann fame) withdrew at the last minute on health grounds he was promoted to the top section.

As you’ll see he found it hard going, but he did record wins against Steinitz and Chigorin, as well as two victories against Mason.

Let’s have a look at a few of his games from this event.

Playing his favourite Stonewall formation against Mason, his pressure on the half-open g-file was crowned with a sacrificial attack.

Lee’s win against Steinitz was also a Stonewall, but here he was rather lucky.

Steinitz had had the better of the opening, but Lee had managed to reach a drawn ending. If Black just waits with his knight White can make no progress, but the ailing former champion, close to the end of his life, seriously misjudged the position, playing 49… Ke4??, after which Lee’s e-pawn wasn’t for stopping.

The following day, black against Chigorin, he faced his opponent’s favourite anti-French move 2. Qe2, gaining a space advantage and giving up the exchange for a passed pawn, and winning one of his finest games.

At his best, Lee was a formidable positional player who could also, when the occasion demanded, display tactical ability. Someone who has, you might think, been unfairly neglected in chess literature.

As the remainder of the year – and the century, seems to have been uneventful for him, this must be a good place to break off.

Join me again soon to discover what the 1900s had in store for Francis Joseph Lee.

Sources and references:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archive

Wikipedia

chessgames.com: FJ Lee here

ChessBase/MegaBase 2024

Stockfish 16

EdoChess (Rod Edwards): FJ Lee here

Two articles on chess.com from Neil Blackburn (simaginfan):

Lee and Gossip. Three Brilliancies. – Chess.com

Belfast 1892. A Chess Tournament and A Grumpy Bird! – Chess.com

Zan Chess: article on New York 1893 here

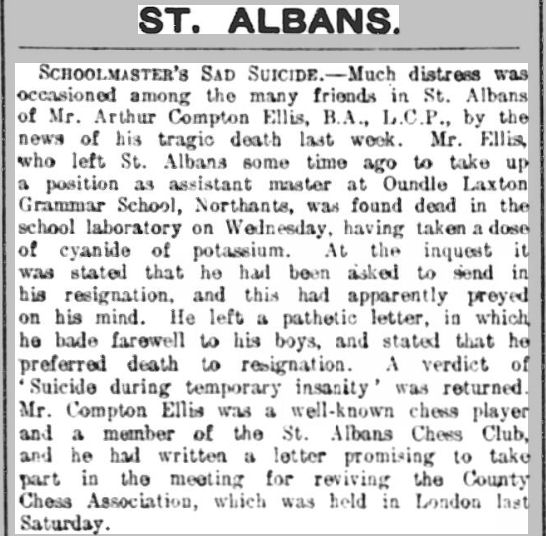

Again, from two years later:

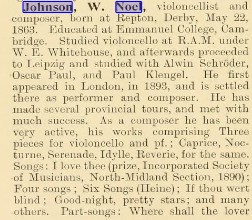

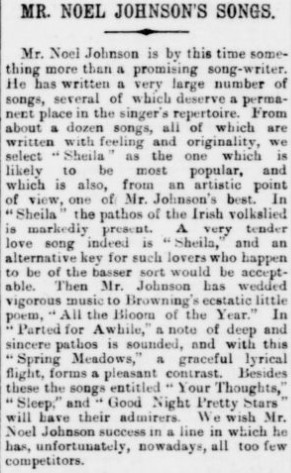

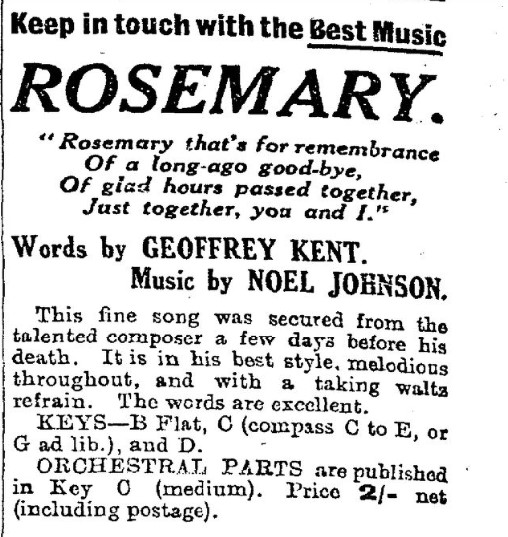

Again, from two years later:  Here we have a successful composer of music mostly for home consumption: songs, short pieces for cello and piano and so on. Music which, perhaps sadly, has now gone out of fashion: I haven’t been able to find any recordings of these songs, but a later work, comprising three short piano pieces, has been recorded for YouTube by Phillip Sear, a specialist in this type of repertoire.

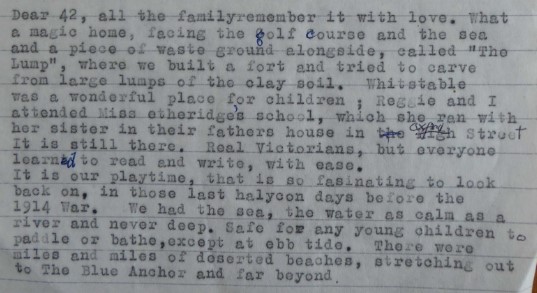

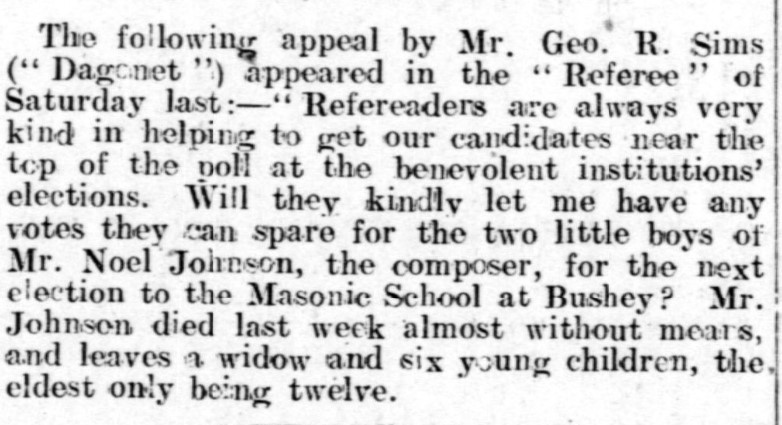

Here we have a successful composer of music mostly for home consumption: songs, short pieces for cello and piano and so on. Music which, perhaps sadly, has now gone out of fashion: I haven’t been able to find any recordings of these songs, but a later work, comprising three short piano pieces, has been recorded for YouTube by Phillip Sear, a specialist in this type of repertoire. But the family’s idyllic seaside life was shattered in January 1916 when William Noel Johnson, now living near Southend, died suddenly of pneumonia, leaving Rosie a widow with six young children.

But the family’s idyllic seaside life was shattered in January 1916 when William Noel Johnson, now living near Southend, died suddenly of pneumonia, leaving Rosie a widow with six young children.

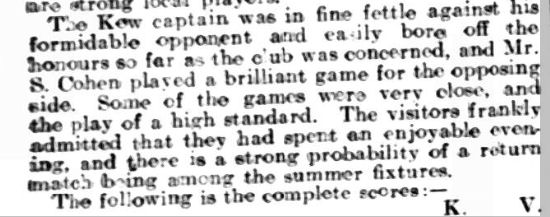

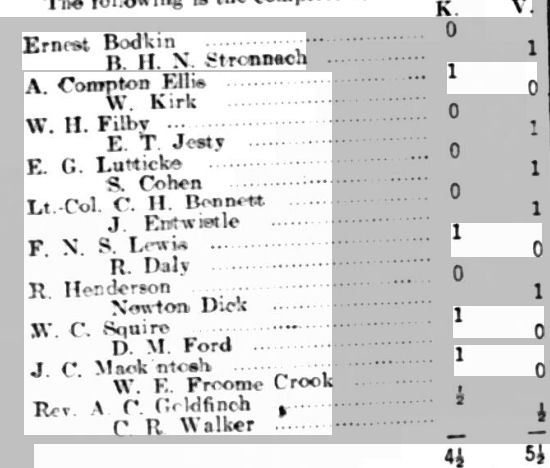

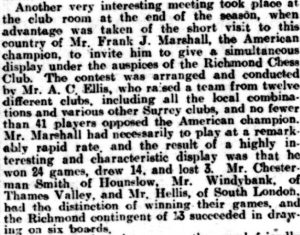

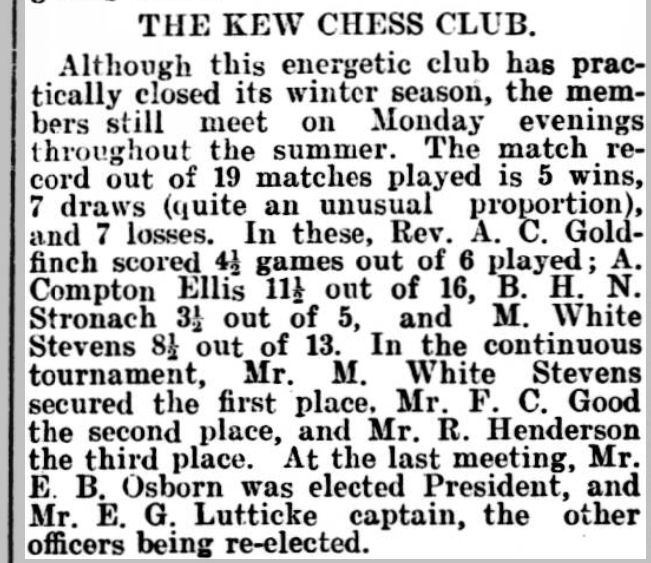

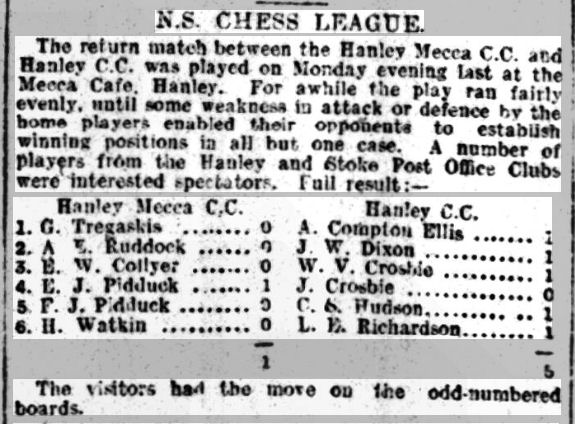

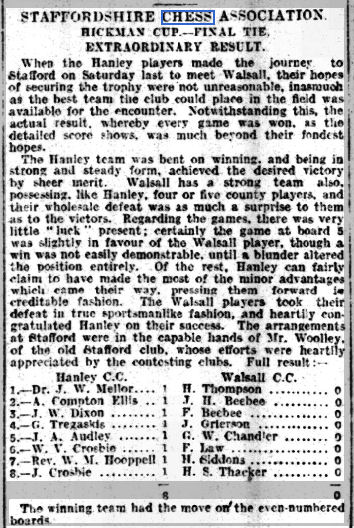

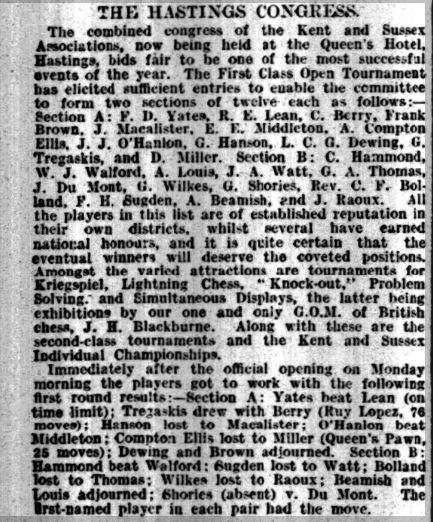

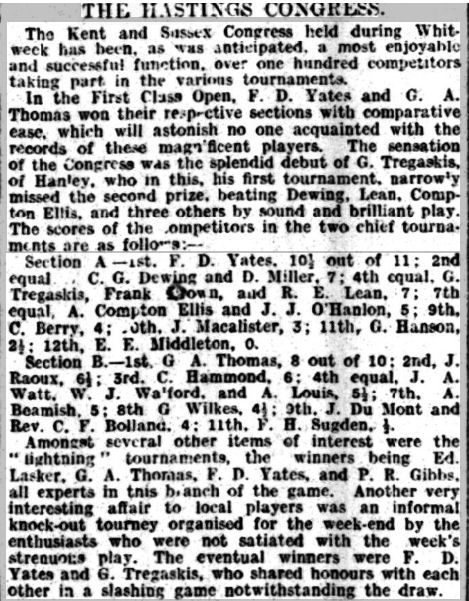

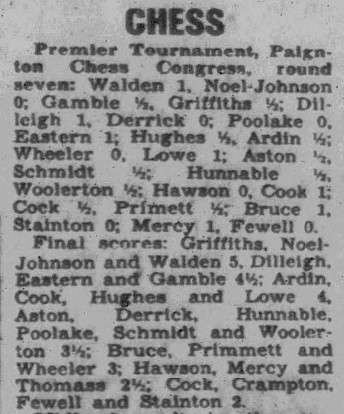

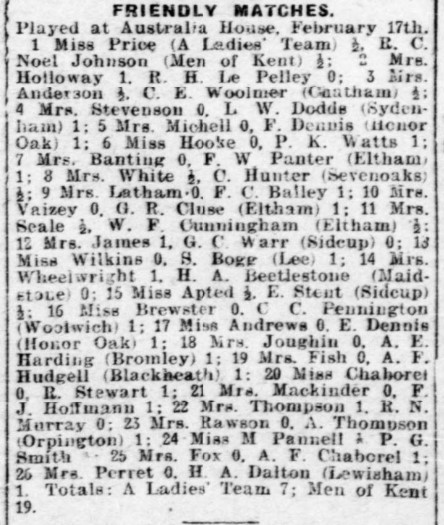

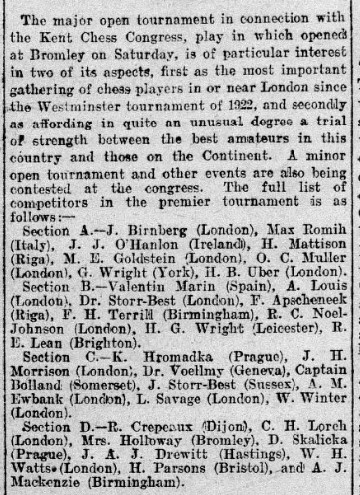

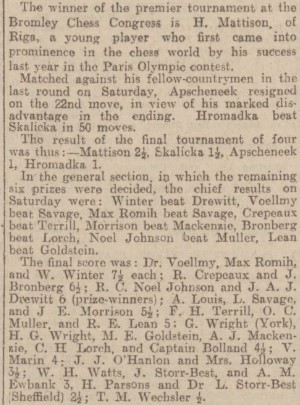

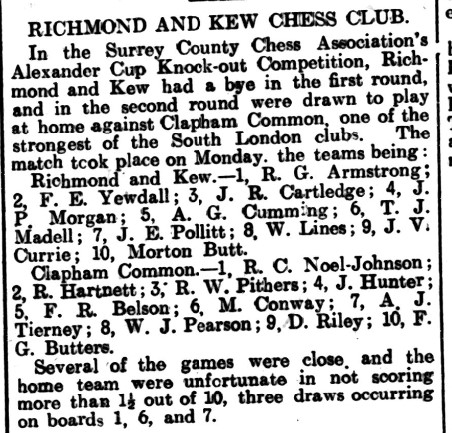

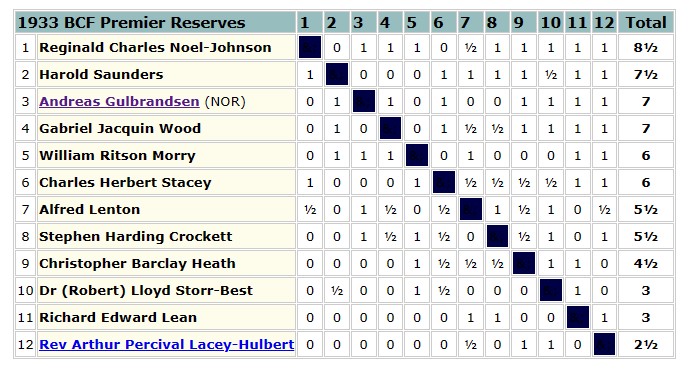

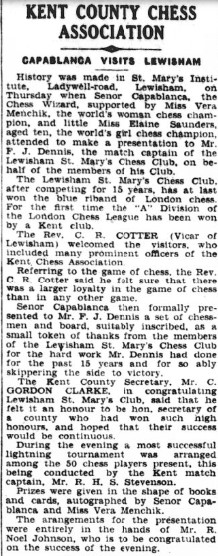

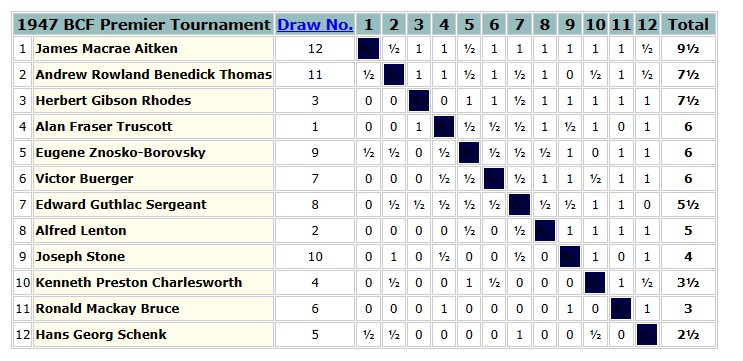

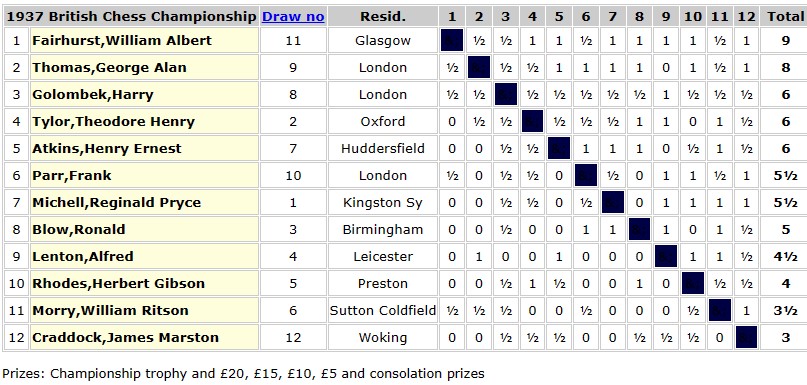

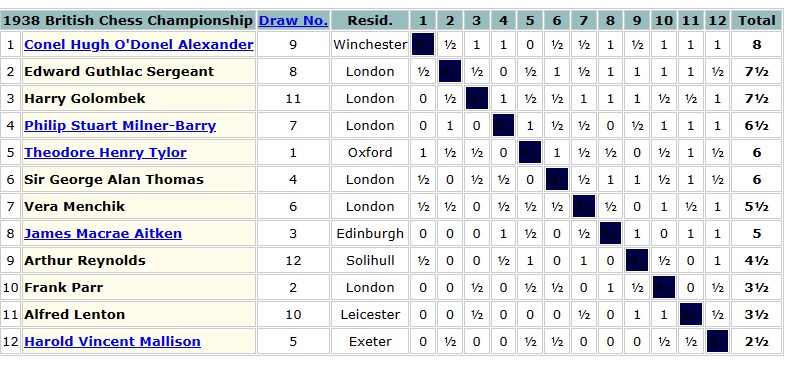

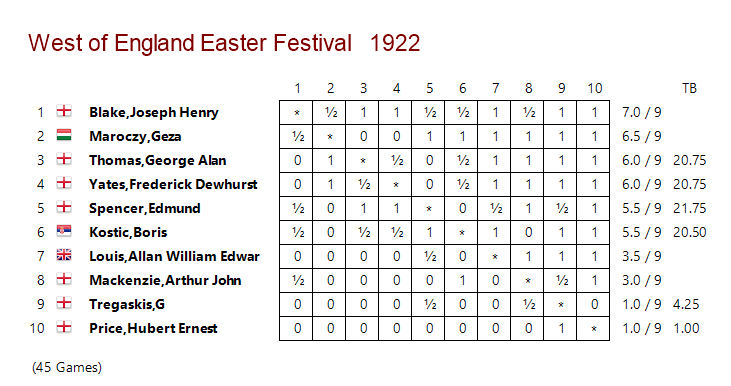

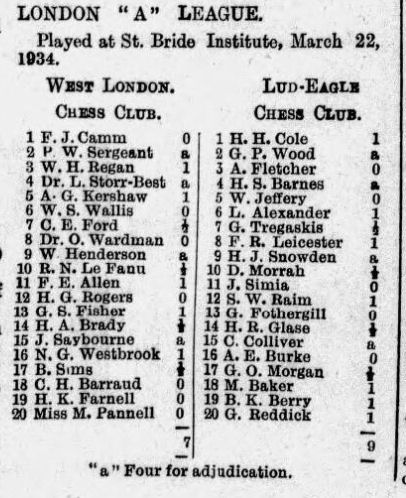

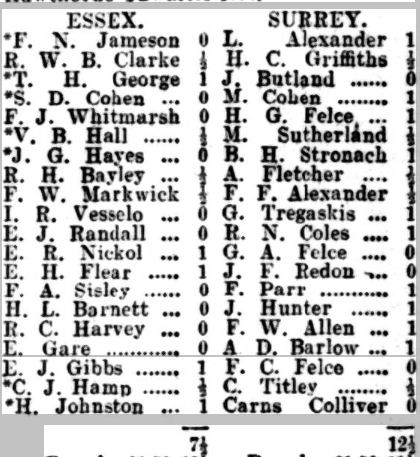

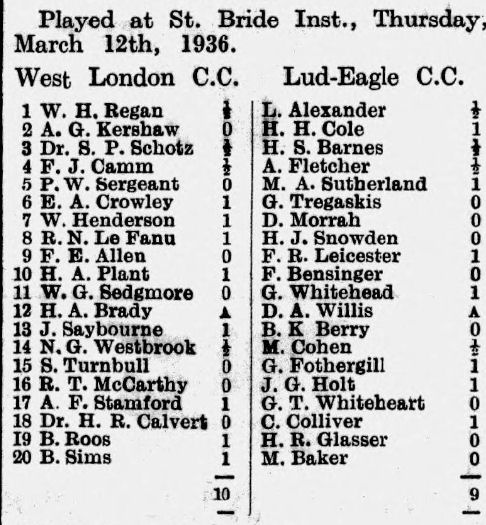

Tournament report

Tournament report

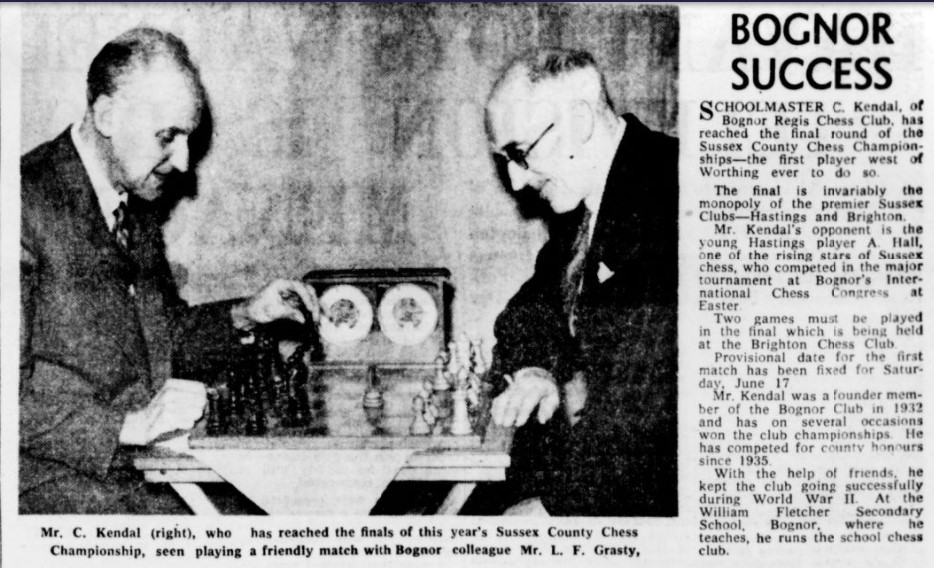

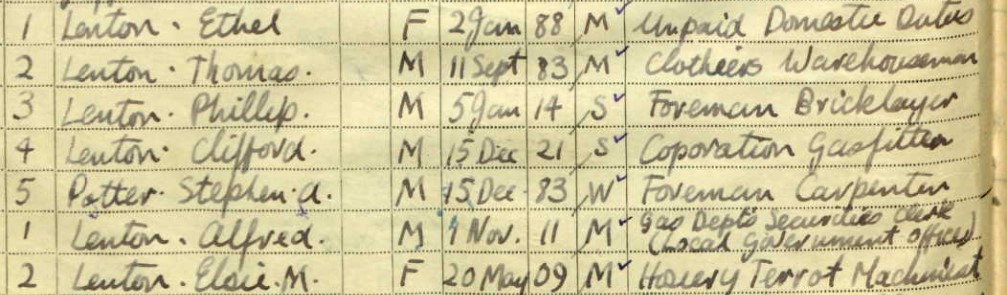

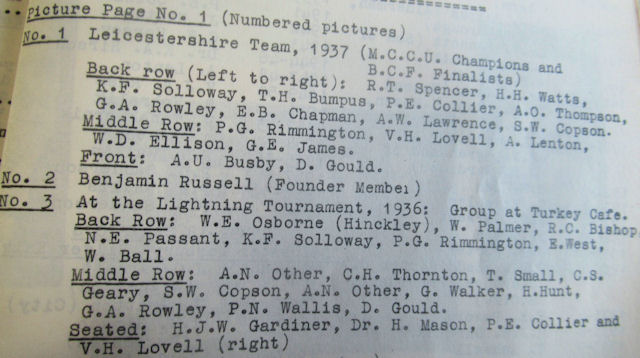

In 1910 this Thomas married Ethel Wood, born in 1888. Ethel was perhaps slightly higher up the social scale: her father, John, was a School Attendance Officer, although his background was also very much working class. Here he is, on the right. John and his wife Sarah had five daughters (Ethel was the fourth), the oldest of whom married into a branch of the Gimson family, followed by a son.

In 1910 this Thomas married Ethel Wood, born in 1888. Ethel was perhaps slightly higher up the social scale: her father, John, was a School Attendance Officer, although his background was also very much working class. Here he is, on the right. John and his wife Sarah had five daughters (Ethel was the fourth), the oldest of whom married into a branch of the Gimson family, followed by a son.

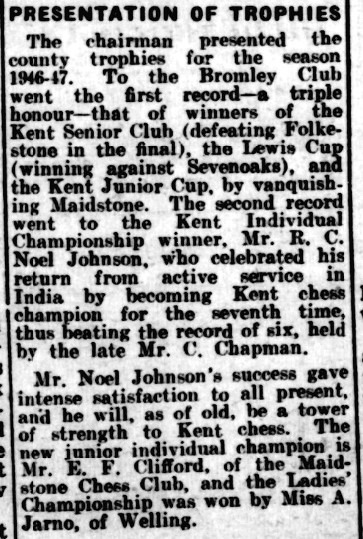

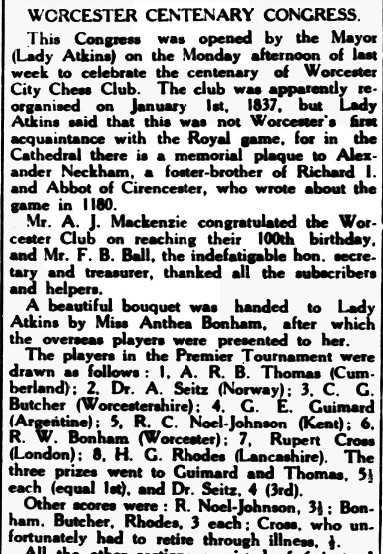

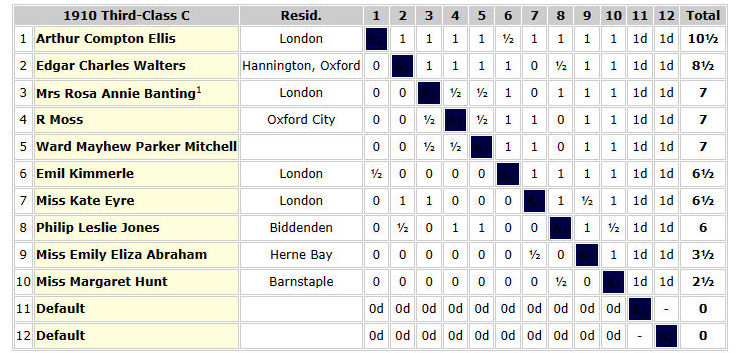

With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than

With a score of 10½/11, it was clear that he was improving fast, and should have been in at least the 2nd Class division. The prizes were presented by none other than