Last time you met, amongst other chess playing Leicester Ladies, Elsie Margaret Reid, a British Ladies’ Championship contender, and witnessed her marriage to Alfred Lenton.

It’s now time to meet her husband.

Perhaps you’ve see Michael Wood’s 2010 documentary series Story of England. If you have, you’ll be aware that it tells its story from the perspective of Kibworth, seen as being a typical village in the middle of the country. In fact it’s two villages in one, owned by different families in the Middle Ages. Kibworth Harcourt is north of the railway line, and, the more significant part, Kibworth Beauchamp (just as Belvoir is pronounced Beaver, Beauchamp is pronounced Beecham), where the shops are, is south of the railway line. There used to be a school there too: a Grammar School founded in about 1359, but in 1964 it migrated to the Leicester suburb of Oadby. You’ll meet one of the new school’s most distinguished former pupils next time.

The Lenton family had been prominent in the village for centuries, perhaps arriving there from the area of Nottingham bearing that name. There’s a brief mention in one of the Story of England episodes, but they don’t seem to have educated their children at the Grammar School.

Join us now on 28 December 1744, when, between the Christmas celebrations and the dawn of the new year, the community welcomed the arrival of Robert Lenton, who was baptised that day. We know his father’s name was Richard, but it’s not entirely clear whether this was Richard the son of Robert, born in 1710, or Richard the son of Richard, born in 1719. I suspect they were cousins, but there’s no way of telling for certain from the extant parish registers. There are reasons to believe – and hope – that it was the older Richard who was Robert’s father.

Robert was a butcher by trade: a significant member of the local community. His youngest son, William, was born in 1787. He married a girl from Bedworth, Warwickshire, in 1811. Maybe he had moved there to seek work, or perhaps she was in service in Leicestershire. They soon returned, settling in Smeeton Westerby, a small village just south of Kibworth Beauchamp.

The first census as we know them today was taken in 1841, and we can pick William up there in both the 1841 and 1851 censuses, where his occupation is given as FWK – Framework Knitter. This was a very common occupation in the East Midlands at the time: William and his family would have been working at home using mechanical knitting machines. By 1851 his oldest son, also named William, had moved into Leicester, but was still working as a framework knitter. In 1853 he married a widow, adopting her children and presenting her with two more sons, William and Thomas.

His younger son, Thomas, very typically for his place and time, spent his working life in the footwear industry, involved in various aspects of making shoes. So here we see a very common pattern of men and their families moving out of villages and into cities where there was plenty of factory work available. His oldest son, another Thomas, also sought factory work, but rather than on the manufacturing side, he worked as a warehouseman for the clothing company Hart & Levy. Sir Israel Hart, one of the company’s founders, was Mayor of Leicester 1884-6 and 1893-94 and President of Leicestershire Chess Club. between 1894 and 1896.

In 1910 this Thomas married Ethel Wood, born in 1888. Ethel was perhaps slightly higher up the social scale: her father, John, was a School Attendance Officer, although his background was also very much working class. Here he is, on the right. John and his wife Sarah had five daughters (Ethel was the fourth), the oldest of whom married into a branch of the Gimson family, followed by a son.

In 1910 this Thomas married Ethel Wood, born in 1888. Ethel was perhaps slightly higher up the social scale: her father, John, was a School Attendance Officer, although his background was also very much working class. Here he is, on the right. John and his wife Sarah had five daughters (Ethel was the fourth), the oldest of whom married into a branch of the Gimson family, followed by a son.

In the 1911 census Thomas and Ethel, not yet able to afford their own house, were living with Thomas’s widowed father and two brothers. He was described as working in the tailoring industry.

On 1 November that year, their first son, Alfred, was born, followed in 1914 by another son, whom they named Philip.

In this family photograph, taken in about 1917, you can see the proud parents with their two boys.

By 1921 the family were living at 27 Halkin Street, north of the city centre (the door of this very typical two up two down Victorian terraced house is open to welcome us in). I would have passed the end of the road regularly in my first year at what was then the Leicester Regional College of Technology, when I was living in digs in Thurmaston. Ethel’s mother had died a few months earlier, and her father was now living with them.

By now Ethel was expecting a third child, and another son, named Clifford was born later that year.

Alfred, a bright, bookish and perhaps rather quiet boy, won a place at Alderman Newton’s Grammar School, where he was a contemporary of the historian Sir John Plumb and a few years below novelist CP Snow, a member of Leicestershire Chess Club during the 1923-24 season.

This was a time when chess was becoming popular amongst teenage boys, and it was when he was 15 that young Alfred learnt the moves. The earliest appearance I can find is in December 1928, at the age of 17, losing his game on bottom board for the Victoria Road Institute (I’d encounter his son playing chess for Leicester Victoria more than four decades later.)

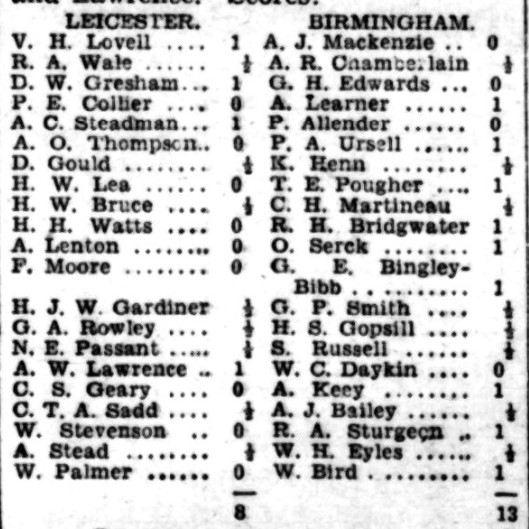

At the Victoria Road Institute, Alfred received some instruction from their top player, building contractor Herbert William Lea, soon making rapid progress. By early 1930 he’d come to the attention of the county selectors, and was one of the promising young players they tried out in a match against Birmingham.

By 1931 Lenton was playing on top board for Victoria Road, taking a high board in the county team and participating in the county championship. Here was a talented and ambitious young man who was clearly going places.

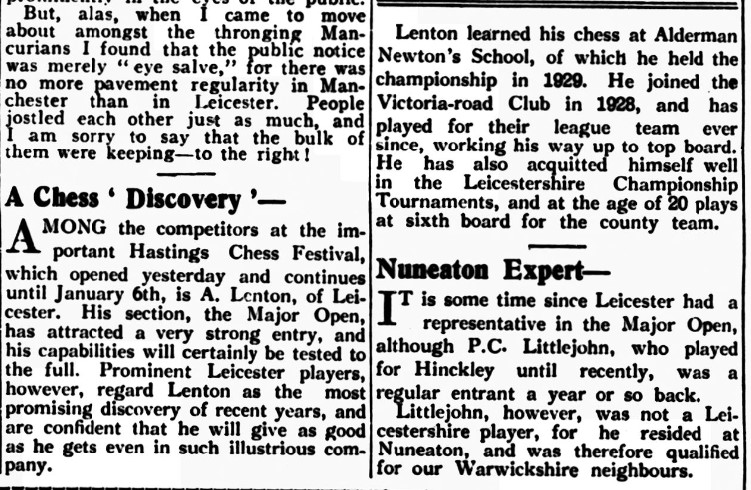

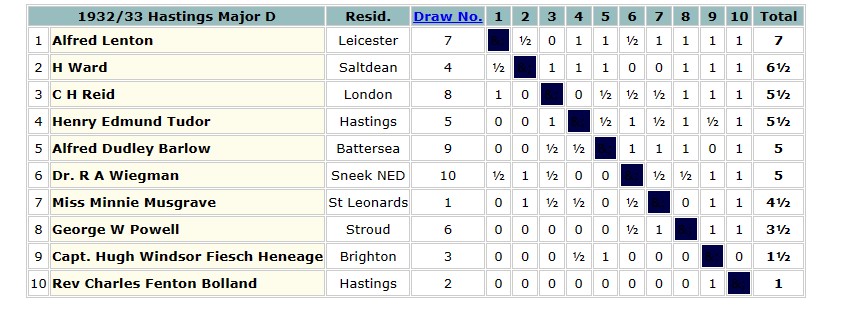

If you’re an ambitious chess player, one of the places you’ll go to is Hastings, and, at the end of that year, he travelled down to the south coast where he was placed in the Major B section.

Here’s what happened.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

This was a whole new experience for him, and it’s not surprising that he found the going tough. In this game his hesitant opening play soon got him into trouble when he was paired against a creative tactician who unleashed a cascade of sacrifices. (Click on any move of any game in this article for a pop-up window.)

Alfred learnt from this experience that he needed to take the game more seriously: in an interview many years later he explained that, at this point, he was studying chess for three hours a day.

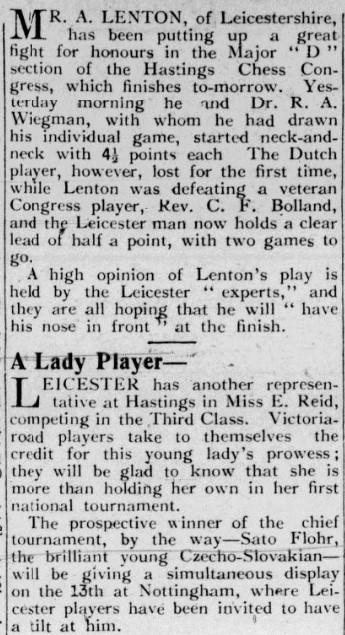

The following year he returned again – and seems to have brought a friend along with him – as you might remember from last time.

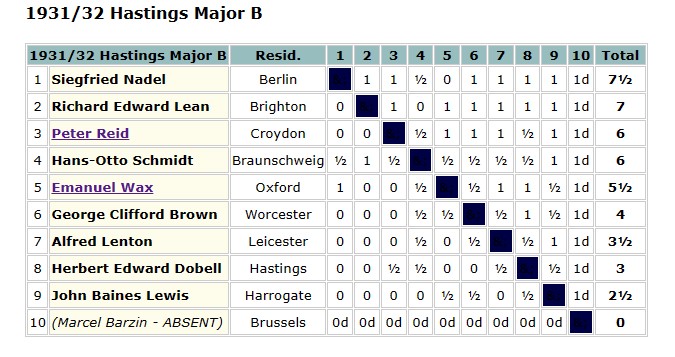

He did indeed maintain his lead to the end of the tournament, as you can see here. Perhaps the opposition was slightly weaker than the previous year, perhaps his hours of study were paying off, or perhaps it was Elsie’s presence that was responsible for his success.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

(As far as I can tell, C(ecil?) H(unter?) Reid, Peter Reid, whom he played the previous year, and Elsie Margaret Reid were totally unrelated.)

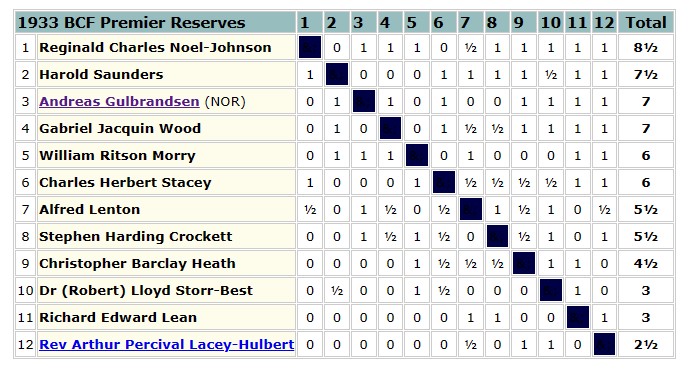

In 1933 the British Championship was held separately from the remainder of the congress, which took place in Folkestone at the same time as the Chess Olympiad.

Alfred was one of a number of promising young players in the Premier Reserves, the second section down: you’ll meet some of them in future Minor Pieces. His 50% score was a good result in such a strong field.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

This game demonstrates that he’d been working on his openings since his first tournament appearance, and concludes with a neat tactic.

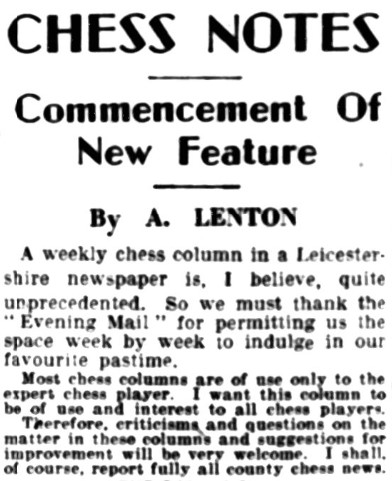

The following month the Leicester Evening Mail had some important news.

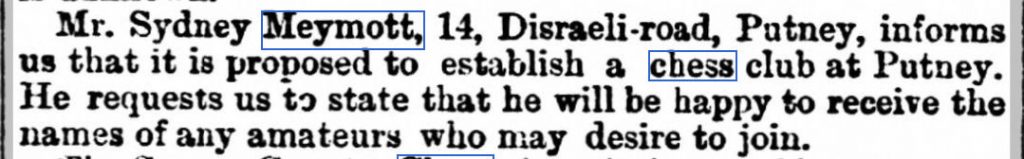

Alfred had got himself a column in a local paper. Each week there would be the latest chess news, a game, which could be of local, national, international or historical interest, along with a puzzle for solving. He was a young man who enjoyed both reading and writing.

Here’s a powerful win against the stronger of the Passant brothers, slightly marred by his 17th move, giving his opponent a tactical opportunity which went begging.

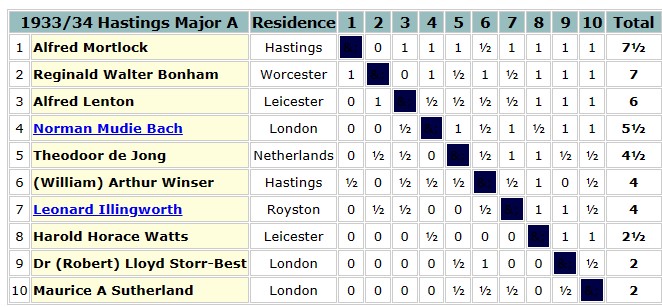

By now established as his county’s second strongest player behind Victor Hextall Lovell, he returned to Hastings after Christmas, where he scored an excellent third place with only one defeat, well ahead of his Leicester Victoria clubmate Watts and former Leicestershire player Storr-Best.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

In this game he missed a win against his Dutch opponent.

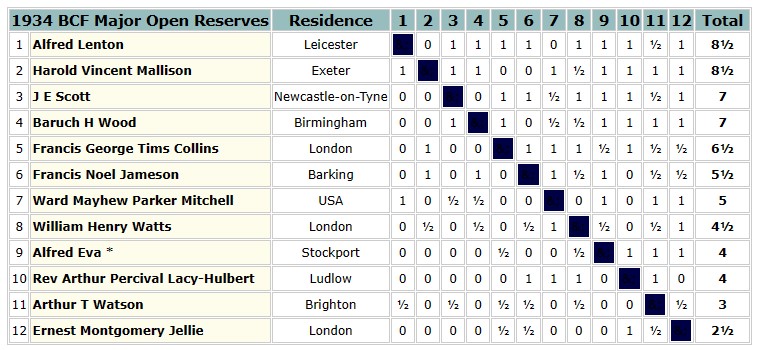

The 1934 British Championships took place in Chester, when Alfred was places in the Major Open Reserves, in effect the third division, while his future wife Elsie (were they engaged at this point?) played in the British Ladies’ Championship.

Lenton was essentially a positional player, but here he unleased a very different weapon when Black against 1. d4 – the dangerous and, at the time, fashionable Fajarowicz variation of the Budapest Defence. It proved rather successful against his clergyman opponent (you can read about him here) in this game, where his opponent miscalculated a tactical sequence, overlooking a queen sacrifice.

His opponent in this game, another talented young Midlands player, will need no introduction.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

You’ll see that he was extremely successful in this event, sharing first place. Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

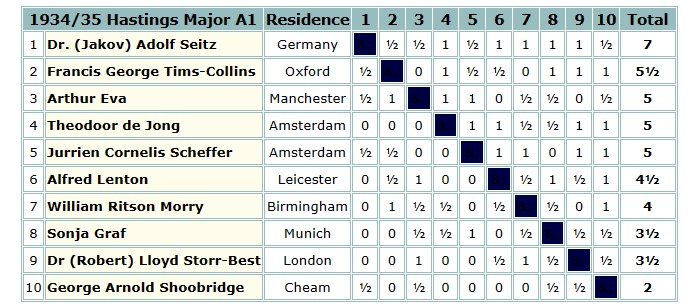

He was rather less successful at Hastings that winter, as you’ll see below.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

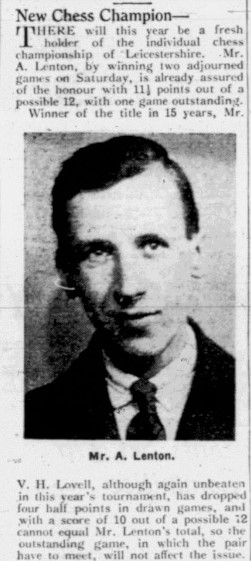

On the home front, though, he was more successful.

Don Gould, in Chess in Leicestershire 1860-1960, sums him up at this stage of his career:

The new champion had left Alderman Newton’s School only six years previously. He was a fine all-round player, with a particularly good grasp of positional play. Unlike Lovell, he had been entering for national tournaments, and profiting by the better practice obtained thereat. Later on he twice won the Midland Counties Individual Championship, and finished in a tie for second place in the British Championship. At that time, he favoured the Reti Opening and the Buda-Pest Defence. Lenton for some years ran a chess column in the local press.

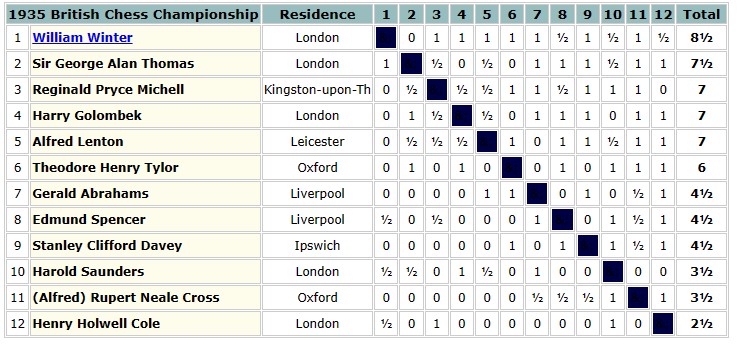

This result (he’d repeat his success the following year) established him as the strongest player in Leicestershire, and, in the 1935 British Championships, held in Great Yarmouth, he was selected for the championship itself.

In this game Lenton displayed his endgame skill after his opponent missed an opportunity on move 17.

Endgame skill, along with hypermodern openings, were the key to his successes at this time of his life. His opponent here was unable to cope with the opening.

Admittedly it wasn’t the strongest renewal of the British, but this was still an outstanding performance, which would have been even better but for a moment of tactical carelessness in the last round.

At this level you can’t afford to give your opponent an opportunity like that.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

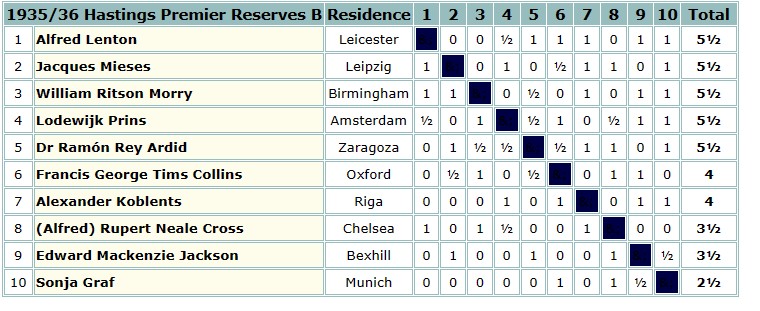

Now top board for his county, and with a new job as a local government officer (he’d transferred his chess allegiance from VIctoria to NALGO) he returned to Hastings over the Christmas holidays. There were so many entries for the Premier Reserves that the organisers decided to run two sections of equal strength, with Alfred in the B section.

He used his favourite variation of the Caro-Kann in this game, grabbing a hot pawn early on (sometimes you can get away with Qxb2) and surviving to dominate the enemy rook in the ending.

You’ll see from the tournament table this was another great success for the Leicester man. It’s perhaps significant that, while all three of his losses were published, the only win I’ve been able to find was the game above.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

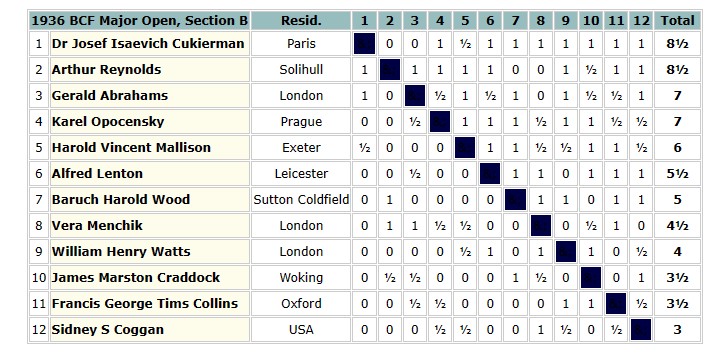

1936 was the year of the famous Nottingham tournament, which took place in August. The British Championship itself took place separately, in Bournemouth in June.

Again, many of the top players were missing, and Sir George Thomas, who would probably have been considered the most likely winner, was out of form. Would Alfred improve on his shared third place the previous year?

Here, he was outplayed in the opening, but his Birmingham opponent miscalculated the tactics, leaving him two pawns ahead in the ending.

He only needed 11 moves to defeat his Ipswich opponent in this game. White’s catastrophic error would be a good candidate for a Spot the Blunder question in the next Chess Heroes: Tactics book.

As you’ll see above, he equalled his previous year’s score, which, this time round, was good enough for a share of second place. There were a lot of talented players in their mid 20s around at the time, and Lenton seemed at this point to be as good as any of them.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

Meanwhile, Alfred had reached the final of the Forrest Cup, the Midland Counties Individual Championship, where he faced future MP Julius Silverman. A rather fortuitous win brought him the title.

Nottingham in August was only a short journey. The Major Open was split into two equal sections, both in themselves fairly strong international tournaments.

This time his performance was slightly disappointing. The three games I’ve been able to find include two losses and this game, where he did well to survive and share the point.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

After the tournament, Alekhine visited Leicester to give a simultaneous display, winning 33 games, drawing 5 and losing 2, one of which was to Lenton.

Alfred’s marriage to Elsie Margaret Reid was registered in the fourth quarter of 1936. They both decided to give Hastings a miss that year.

His favourite Réti Opening wasn’t always successful against stronger opposition, but it could be devastating against lesser lights, as shown in this game from a county match.

In May that year, Alfred made his international début in the inaugural Anglo-Dutch match, scoring a win and a draw (he was losing in the final position) against Klaas Bergsma. He also won the Forrest Cup for the second time.

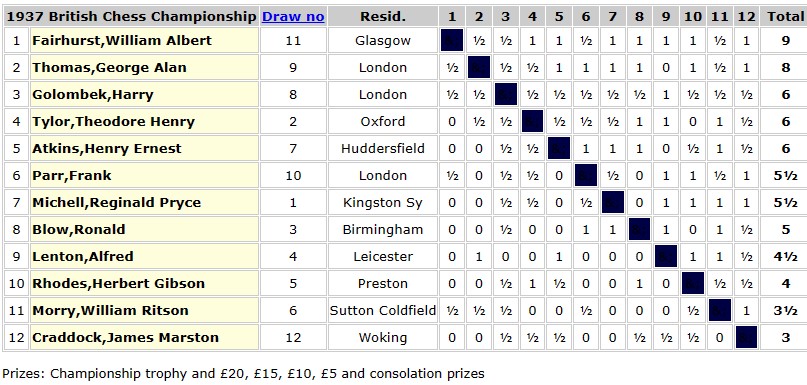

Then it was on to Blackpool for the British Championship. Would he improve on his performances in the two previous years?

It was soon clear that the answer would be no. Something was clearly wrong in the first week, when he lost his first five games. Was he unwell? Who knows? But he fought back well to score 4½ points from his last six games, including wins against two venerable opponents.

Winning this game against a man who must have been one of his heroes, 9 times British Champion and Leicester’s finest ever player, now in the twilight of his career. A powerful pin on the e-file proved decisive.

Against the tournament runner-up he demonstrated his knowledge of Réti’s hypermodern ideas: note the queen on a1. His position wasn’t objectively good, but it seemed to leave Sir George confused.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

Two games from this period demonstrate again how lethal his queen’s bishop could be in his favourite double fianchetto set-up. You might want to see them as a diptych: both being decided by a Bxg7 sacrifice.

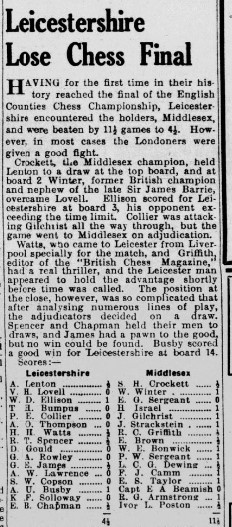

In 1937 Leicestershire reached the final of the English Counties Championship.

We have two photos and a report.

Now into 1938, Alfred won the Forrest Cup for the third time, his final game producing another sacrificial finish.

He again scored 1½/2 in the 1938 Anglo-Dutch match, this time paired against Chris Vlagsma. His opponent was doing well here before ill-advisedly opening the f-file.

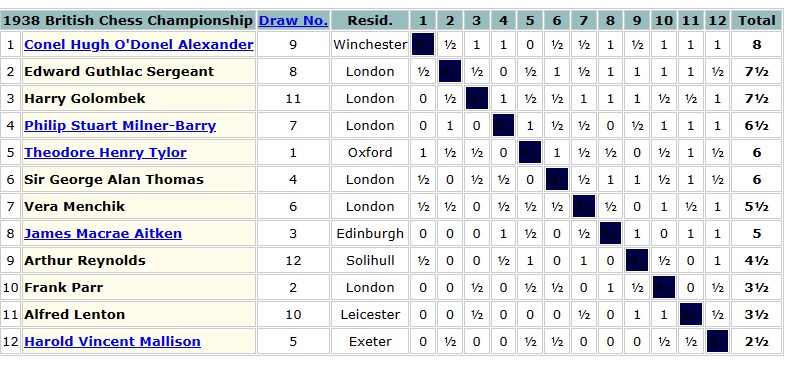

Then it was down to Brighton for the 1938 British Championship, which proved to be another disappointment.

The low point was a loss in only 9 moves against Tylor.

In the very next round, though, switching from his usual Réti, he won in 13 moves when Frank Parr got his queen trapped. This time capturing his opponent’s b-pawn with his queen wasn’t a good idea.

It’s not clear what had happened to his chess here. I suspect that, with the twin demands of his job and married life, he was no longer putting in the three hours study every day.

Here, from Battersea Chess Club’s obituary of Parr, is a photograph, with Lenton on the right considering his move.

And here, as you see, he finished in a share of 10th-11th place, quite a comedown from his results of 2 and 3 years earlier.

Full tournament report (and larger format crosstable) here.

In spite of this result, he was selected for the 1939 Anglo-Dutch match, where he was up against Carel Fontein, drawing one game and losing the other.

How strong was he during this period? EdoChess gives his rating peaking at 2250 in 1936, so, although he finished high up in the British on two occasions, he was only, by today’s standards, a strong club player. A player with considerable ability, both tactical and positional, but also with some weaknesses.

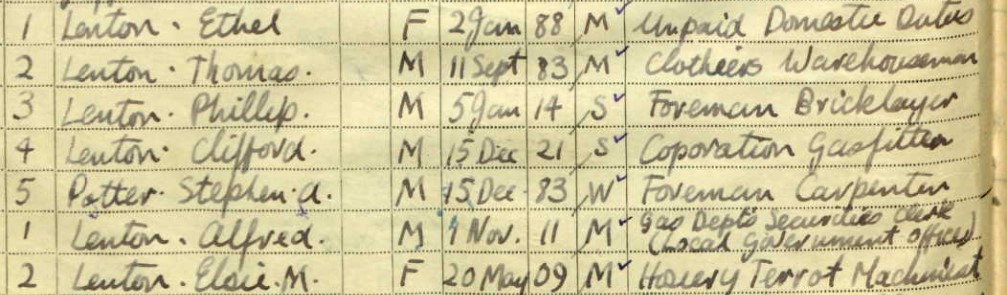

Storm clouds were gathering over Europe, war was declared on 1 September 1939, Lenton’s chess column was wound down, perhaps anticipating a paper shortage. A register was taken on 29 September listing all residents, for the purpose of producing identity cards and ration books.

Alfred and Elsie were recorded two miles east of the city centre, at 65 Copdale Road, Leicester (on the left here), living next door to his parents and brothers at number 63 (with the blue van up the drive: looks like it might have been rebuilt). The family had moved up in the world since 1921.

While Elsie is knitting socks with her circular machine, Alfred is a Gas Department Securities Clerk, working for the local government office.

At this point it’s almost time to break off our story, just noting that our hero had won his third county championship, receiving the trophy in October. “A worthy champion, who will be British Champion one day”, said the county President Robert Pruden on presenting the trophy. You’ll find out how accurate that prediction was in our next Minor Piece, when we look at what happened next in Alfred’s life.

But first, let’s return to Kibworth Beauchamp, where our story began. We met Robert Lenton, born in 1744, who might have been the son of Richard born in 1710. He had a brother named Mark (a very popular name in this family) who moved to the nearby village of Thorpe Langton. We travel down the generations, another Mark, Henry, and his daughter Ann, baptised on 27 July 1794. On 2 December 1816 Ann married Thomas James, from the small village of Slawston, a few miles further east. We travel down the generations again, another Thomas, who moved back to Thorpe Langton, John, Tom Harry, and to the youngest of his 18 children, Howard, who was my father.

Which makes Alfred possibly my 6th cousin twice removed, or if Robert’s father was the other Richard, my 7th cousin twice removed (I think).

Another golden chain. Even though I didn’t inherit his talent, I’m delighted to be a kinsman of someone who finished =2nd and =3rd in two British Championships.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

BritBase (John Saunders)

John Saunders also for providing me with his Lenton file

ChessBase/Stockfish 16

chessgames.com

EdoChess (Rod Edwards)

Google Maps

Wikipedia

Chess in Leicester 1860-1960 (Don Gould)

Battersea Chess Club website

shropshirechess.org