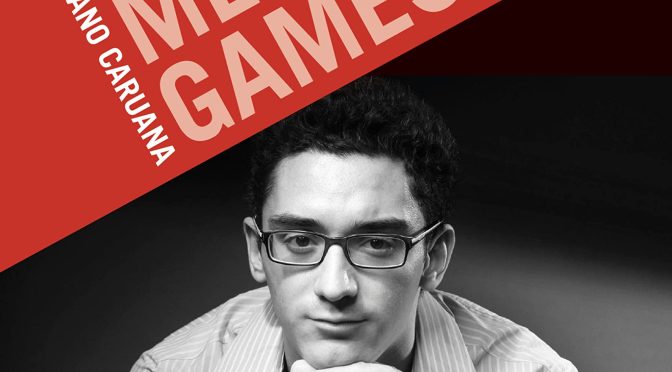

From the Batsford web site:

“Following on from the enduring success of one of the most important chess books ever written, Bobby Fischer: My 60 Memorable Games, and the recently released Magnus Carlsen: 60 Memorable Games, celebrated chess writer Andrew Soltis delivers a book on Fabiano Caruana, the Grandmaster set to rival current world champion Magnus Carlsen.

This book details Caruana’s remarkable rise from chess prodigy to one of the best chess player in the world, exploring how he acquired the skills of 21st-century grandmaster chess over such a short period of time.

This book dives into how he wins by analysing 60 of the games that made him who he is, describing the intricacies behind his and his opponent’s strategies, the tactical justification of moves and the psychological battle in each one.”

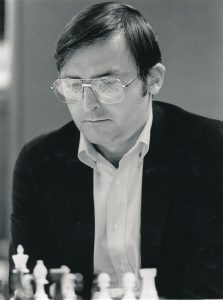

About the Author:

“International Grandmaster Andrew Soltis is chess correspondent for the New York Post and a very popular chess writer. He is the author of many books including What it Takes to Become a Chess Master, Studying Chess Made Easy and David Vs Goliath Chess.”

If you’ve read and enjoyed the companion volume on Carlsen, you’ll want this as well. Many readers collect games collections, and will be eager to add a book on one of today’s leading practitioners to their shelves. This isn’t the only book on Caruana available: there’s one, for example, by Lakdawala, a writer with a very different style. If you like Soltis’s annotations you may well not like Lakdawala’s, and vice versa. They’ve both been doing what they do for a long time and understand their readership.

Here, then, we have sixty of Caruana’s most interesting games, not all of them wins, mostly from the last decade, but a few earlier, starting with a game from 2002. Most are standardplay games, but there are also a few rapid, blitz and internet encounters.

In his introduction, Soltis looks at what makes Caruana different from other top players.

And if he had a celebrity personality – that of a Magnus Carlsen, a Bobby Fischer or a Garry Kasparov – his story would be known well beyond chess circles. But Caruana is Caruana. “He is shy and modest, like a conservatory student”, one of his teachers said. He is content to let his moves do most of the talking.

He identifies several traits in Caruana’s play.

- He’s a concrete player, relying on calculation more than intuition.

- He doesn’t only rely on computer analysis, using curiosity and self-discipline to investigate the secrets of a position.

- He believes the board and the pieces, playing the way the pieces tell him to play regardless of the tournament situation.

- He is able to manage his nerves and emotions.

- He chooses moves that push his opponents out of their comfort zone.

- He is very patient, often playing quiet ‘little moves’ which slightly improve his position.

- He employs deep opening preparation, much more than, for example, Carlsen.

- An occasional flaw in his play is that he sometimes fails to deliver the knockout blow.

- He has emotional stamina: he can deal with his mistakes and knows how to react when things go wrong.

The introduction also tells about Caruana’s early life in New York, and about the influence of the Soviet Chess School on his studies there.

Then we have, yes, sixty memorable games, each prefaced with a catchy title and a brief introduction. Just like another book of 60 Memorable Games.

The best way to describe this book, is, perhaps, to show you a few examples of Soltis’s style of annotations.

This is from Caruana – Aronian (Sao Paulo 2012).

Members of Caruana’s generation grew up with computers and Kasparov games. Many of them had little interest in games played before 1990.

Hikaru Nakamura called the classic books “a waste of time” and complained to his father, “Why do I have to study dead people?”.

Caruana studied them. He understood how White can benefit from d4-d5 in this pawn structure, as Bobby Fischer had in a celebrated game against Viktor Korchnoi.

16. d5

But in another textbook game (Tal – Panno Portoroz 1958) White scored with the alternative plan e4-e5. Here 16. e5! dxe5 17. dxe5 opens the b1-h7 diagonal. This does a better job than 16. d5 of exploiting the diversion of Black’s bishop to h5.

Black cannot protect his knight after 17… Nd5 18. Be4! with Be6.

Also unfavourable for him is 17… Nd7 18. axb5 axb5 19. Be4.

What do you think? Helpful? Informative? Instructional? Interesting?

This is from another Caruana – Aronian game, this time played in the Sinquefield Cup in 2014. Caruana has just played 13. Bd2.

The pawn structure created by 11. Bxe6 gave Black a choice of four basic policies:

(a) Leaving the pawn structure intact. He could pursue a kingside plan such as 13… Qe8 and … Qh5/… Ng6.

(b) Change it by trading knights with 13… Nd4. His pieces would be freed a bit by 13… Nd4 14. Nxd4 exd4 15. Ne2 c5. This would expose his queenside to greater pressure after 16. a4 and Qb1 – b3.

(c) Attack the queenside. Thanks to 13. Bd2, White can respond to 13… Qd7 14. Na2 a5 with 15. c3. Black can add 15… d5 into the mix, with uncertain prospects.

13… d5

Aronian chooses (d), Gain space with this move, followed by … Qd6 or … Bd6 and potentially … d4/… a5.

The reader learns from this how to create plans based on the pawn formation, specifically with regard to this position, and perhaps also more generally.

Do you like this style of annotation, or would you prefer something rather less dry? Perhaps you’d go to the other extreme, hoping to sees long computer-generated variations to demonstrate these plans.

Finally, another Sinquefield Cup game, this time with Caruana playing white against Nakamura in 2018, and considering his 26th move.

It was time for long-range thinking:

White could try for e4-e5 after offering an exchange of queens: 25. Qf4.

But even after 25… Qe7 26. e5 Bd5 it is not clear he is making progress.

For instance, 27. Nxd5 exd5 28. Rxd5 c3 or 28… Qb4.

If e4-e5 isn’t a good plan, what about a kingside pawn march?

This would show promise after 25. g4 Be8 26. h4.

For example, 26… Bc6 27. g5! hxg5 28. hxg5 and Qh4/Rh1.

But the attack abruptly halts if Black swaps rooks, 26… Rd8! 27. g5 Rxd2 28. Rxd2 hxg5 29. hxg5 Rd8 30. Rxd8 Qxd8.

Then White’s knight has few good squares. But Black’s queen does (31. Qc5 Qd2 or 31. Qf4 Qd4).

25. Qc5!

Psychologically, the best move.

It gives Black a choice of playing an inferior endgame – which is likely to be drawn – or giving up a pawn he might lose anyway.

Nakamura mistakenly went for the inferior ending and eventually lost.

Did you find this clear and easy to follow, or confusing and hard to follow? Or just about right?

Whether you’ll enjoy this book, then, is very much about whether you like Soltis’s style of annotation. Me, I’ve been a long-term fan so I enjoyed the book very much, but it’s very much a matter of taste, isn’t it?

If you appreciate annotations of this nature, you won’t want to miss this. You can, of course, be sure that you’ll get 60 top class games from recent elite GM praxis, expertly selected and with commentary from one of the most experienced writers in the business.

Games collections such as this are popular with many readers, and all chess book collectors with an interest in contemporary grandmaster chess will want at least one book about Caruana on their shelves. If that describes you, you’ll certainly want to consider this book.

You might well ask how much a club standard player can learn from the games of someone 1000 or so points stronger. It’s a good question, but I think Soltis does a pretty good job of making the games both accessible and instructive.

The book is well produced to Batsford’s usual standards, although one or two diagram and notation errors escaped the proofing. I don’t care much for the title of this or the companion Carlsen book, which some might consider disrespectful to Fischer, but I guess the publishers choose the title they think will sell most copies.

If the extracts I’ve presented appeal, you won’t be disappointed. An excellent book from a highly respected author recommended for competitive players of all standards, for connoisseurs of fine chess, and for all interested in chess culture.

Richard James, Twickenham 25th February 2023

Book Details :

- Paperback: 442 pages

- Publisher: Batsford; 1st edition (3 Mar. 2022)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:184994721X

- ISBN-13: 978-1849947213

- Product Dimensions: 15.24 x 3.49 x 23.5 cm

Official web site of Batsford