If you’re travelling by train to visit the Chess Palace you’ll alight at Whitton station and turn left from where it’s a fine and fancy 20 minute walk – or you can take the crosstown bus if it’s raining or it’s cold.

If you turn right instead you’ll find yourself in Whitton High Street, with a turning into Bridge Way (named after the railway bridge, not the card game) on your right. If you walk along Bridge Way you’ll find two turnings on your left, Cypress Avenue and Short Way (not named after Nigel, but because it’s a short way), which leads into Redway Drive. Not many of its residents will be aware that it’s named after a chess player.

Much of what is now Whitton was built up in the interwar years on land which had previously been farms and market gardens. Twickenham’s international rugby stadium was known informally as Billy Williams’ Cabbage Patch because a man of that name had grown vegetables there. This explains the name of the Cabbage Patch pub opposite Twickenham Station, well known both as a rugby pub and a music venue.

The exception was the land adjacent to the Hounslow Gunpowder Mills, which is where you’ll find the Chess Palace, but that’s another story.

In this aerial photograph from 1931 you can see the railway line, the newly opened Whitton Station, the first shops in the High Street and, in the centre, Short Way, leading to Redway Drive, with trees behind it. It meets Nelson Road on the left and, at the junction with Short Way, curves to the right where it would, by 1933, meet the A316 Great Chertsey Road. The rugby ground can be seen in the distance.

Mr Redway gave his name not just to the road but to the whole estate, as you can see from this photograph from a few years later.

Here’s the road itself: typical 1930s suburban architecture, newly planted trees and a notable shortage of cars.

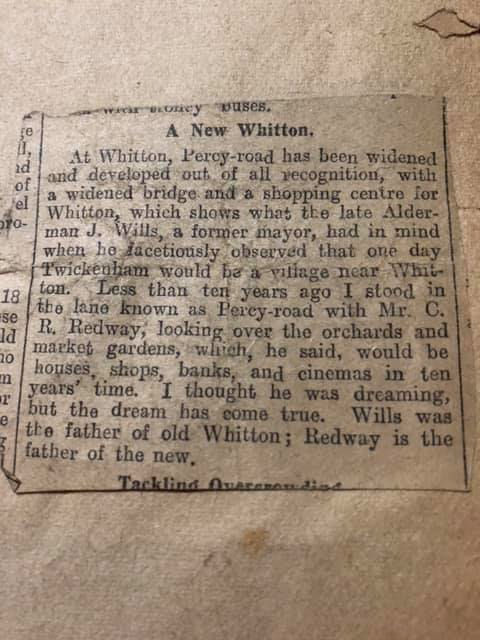

Here’s a cutting from, I guess, the mid 1930s: found on Facebook without attribution but probably from the Richmond & Twickenham Times. Typically, the local press got Mr Redway’s middle initial wrong: he was Charles Percy Redway (1885-1953).

Redway was a stockbroker by profession who had presumably bought up the land speculatively and sold it for housing. Perhaps the proceeds had enabled him and his family to move from St Margaret’s Road Twickenham to Grove House, Hampton in 1927. Very nice too. Lucky chap!

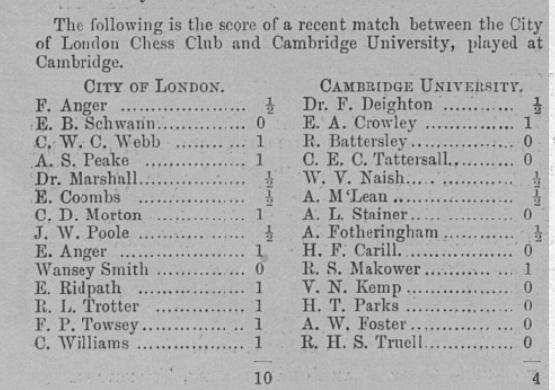

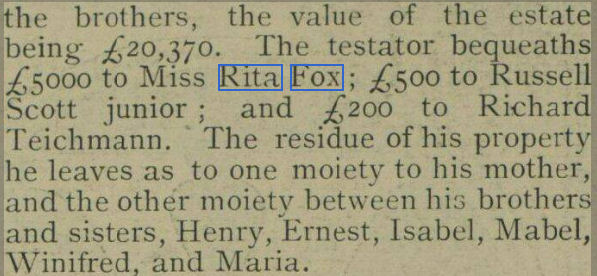

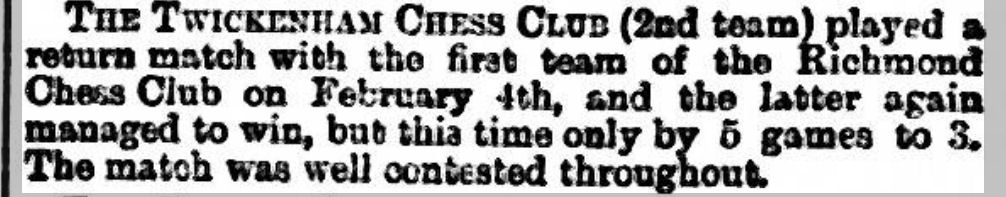

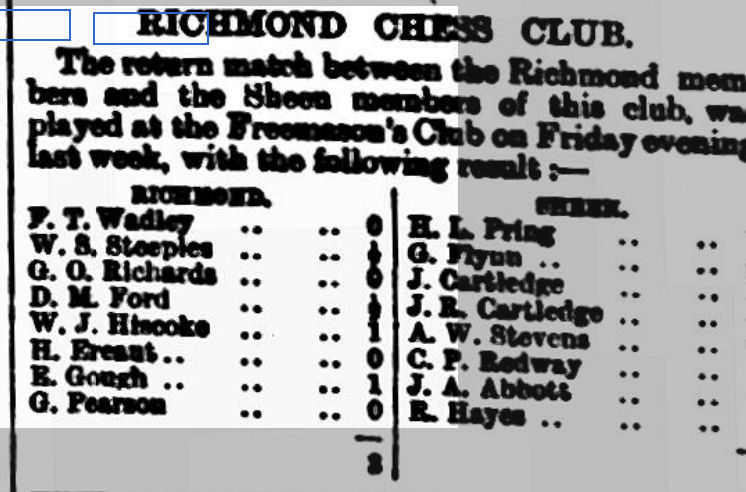

Back in his teens, Charles Percy was a chess player, but as with many young players, life got in the way. In 1904 he was a member of Richmond Chess Club, taking part in matches between the residents of East Sheen and the rest. Here’s an example in which he was successful.

These, I’d imagine, were more social events than serious matches: the players on the higher boards were also seen in competitive matches against other clubs, but the lower boards, such as young Charles Percy Redway, gained experience from events such as this. His opponent here may have been Herbert Ereault, a bank clerk from Jersey, only three years his senior.

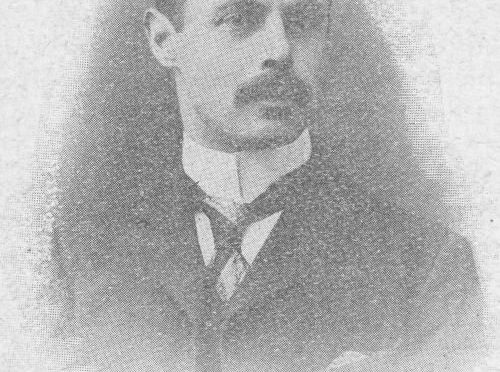

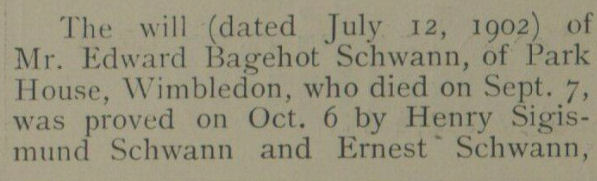

But Charles Percy Redway isn’t the real subject of this article: his father, plain Charles Redway, was a much stronger player, from a family involved in various chess related activities.

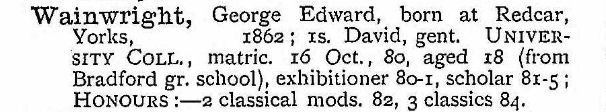

Charles Redway senior had been born in Paddington in the fourth quarter of 1861. His father, another Charles, had been born in Teignmouth, Devon and his mother, Mary Ann Richardson, near Corby in Northamptonshire. It looks like they had met while working in service in London. We can pick up our protagonist in the 1871 census: the family are living in Chelsea where his father is working as a butler. He is the second of five children at home: a sixth child would arrive later. By 1881 the oldest Charles is buttling for Scottish poet, biographer and translator Sir Theodore Martin in Onslow Square, Kensington, while Mary Ann is in the family home in Bywater Street, a 15 minute walk away, along with her father and six children: George, the eldest is a Publisher’s Assistant while Charles is a clerk and the only daughter, Mary Jane, a dressmaker.

The Redway family was clearly bookish as well as chess playing. Did this come from within the family or was their love of books inspired by Sir Theo? Where did the family’s love of chess come from?

Charles married Emily Jones in 1884 and by 1891 they were living in Elm Road, Mortlake, just round the corner from where you’ll now find the East Sheen branch of Waitrose, along with their four young sons (Charles Percy was the oldest), a 14-year-old domestic servant and Emily’s younger sister Ida. Charles’s occupation is given as an Assurance Clerk: he was employed by the Prudential Assurance Company.

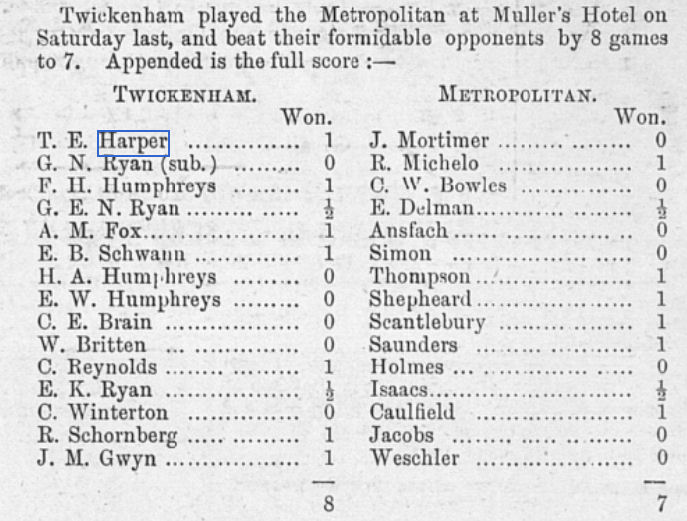

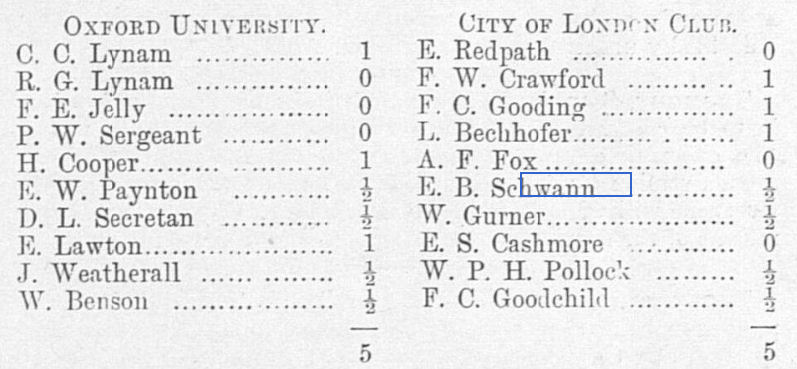

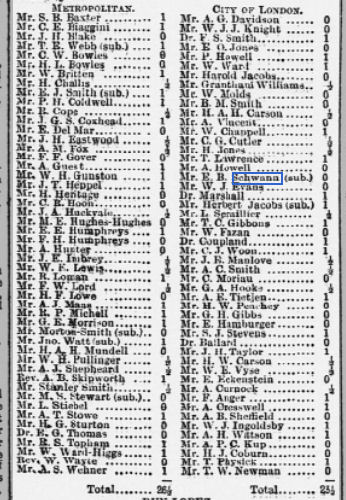

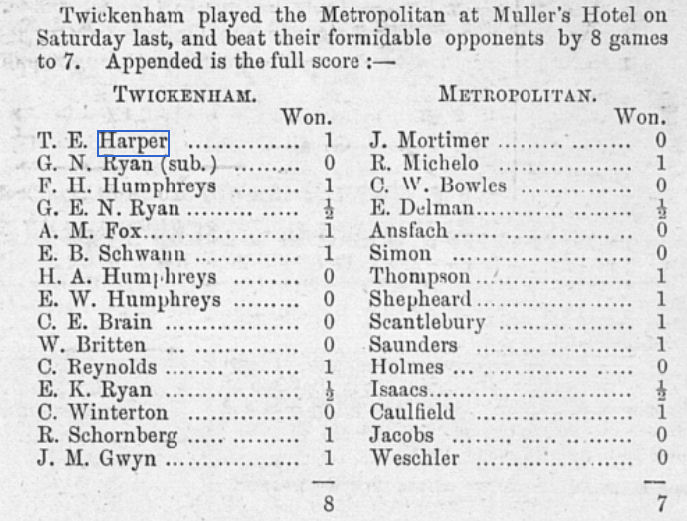

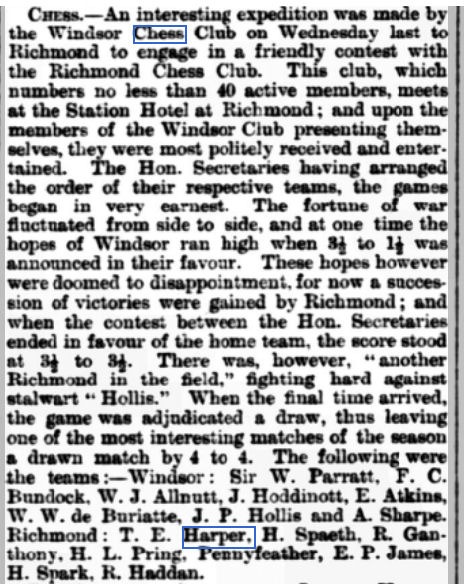

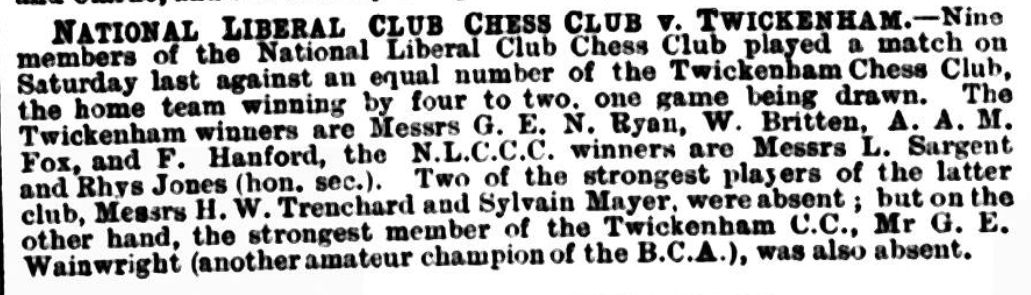

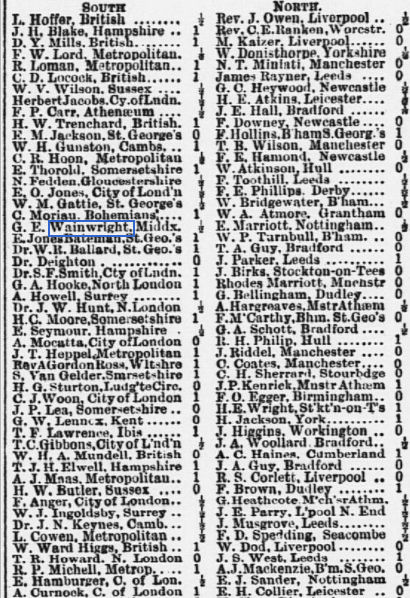

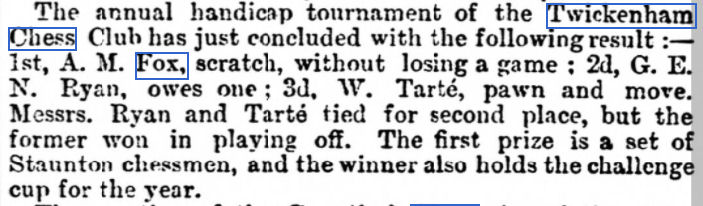

At some point in this decade he joined the young and ambitious Richmond Chess Club. His first sighting in the chess world seems to be in an 1896 match over 100 boards between teams representing the North and South of the Thames. Charles was on board 38, winning his game against a reserve, T A Bedford.

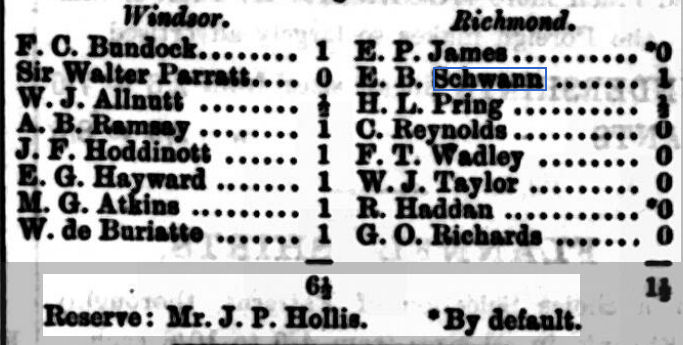

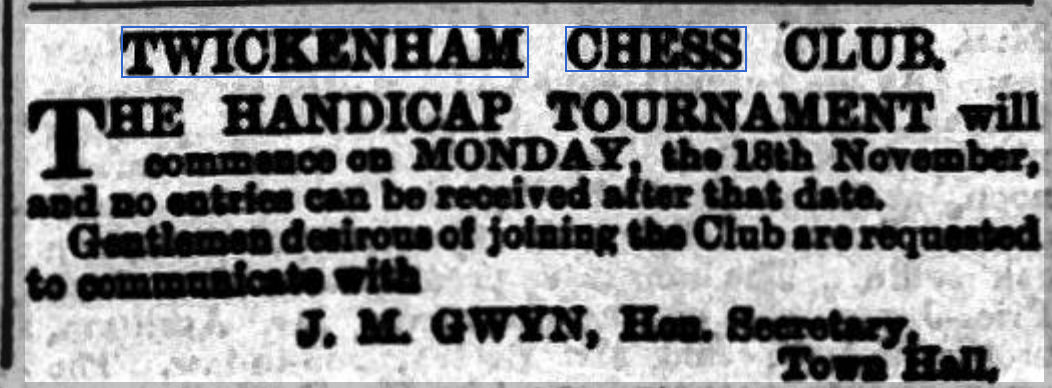

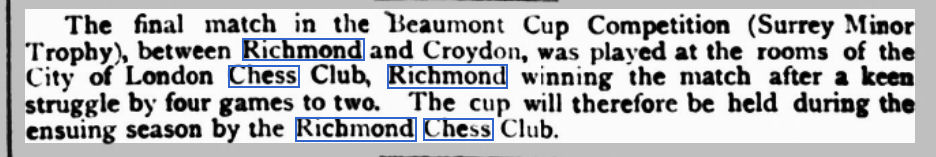

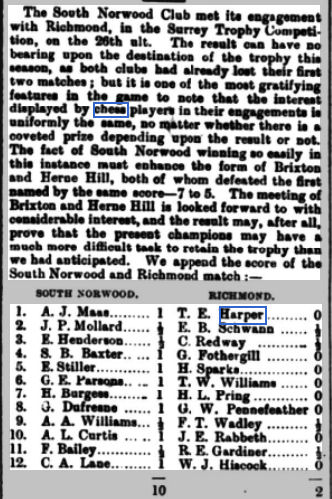

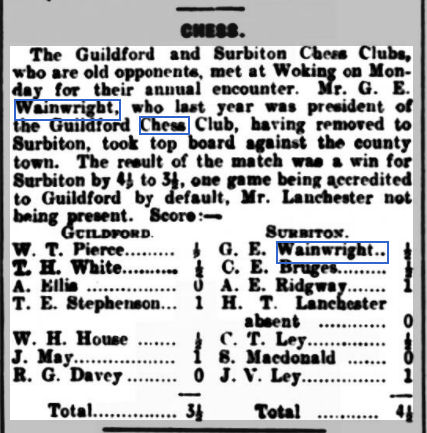

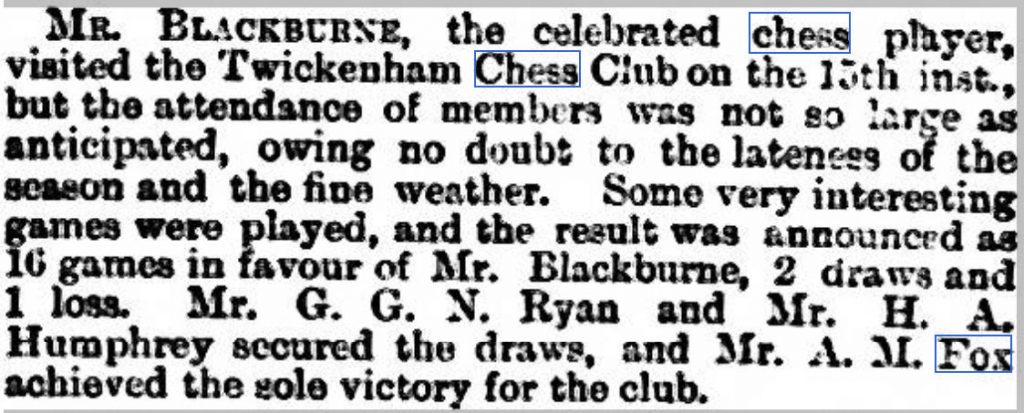

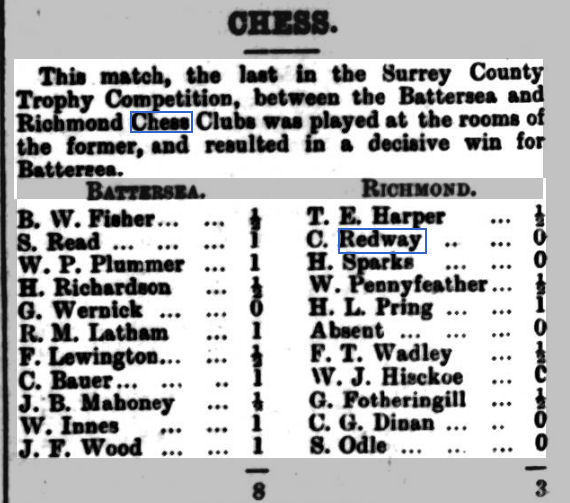

Here he is playing board 2 behind Thomas Etheridge Harper in a Surrey Trophy match against Battersea in 1898. Richmond were well beaten, not helped by a default, something that was only too common in their matches at this time. Their ambition in taking on top clubs like Battersea in the Surrey Trophy, when they could have opted for less demanding opposition in the Beaumont Cup, seems not to have been matched by their competence in making sure all their players turned up.

You’ll find an excellent article about the Battersea board 3 William Philip Plummer here on their club website, and more about their club history here.

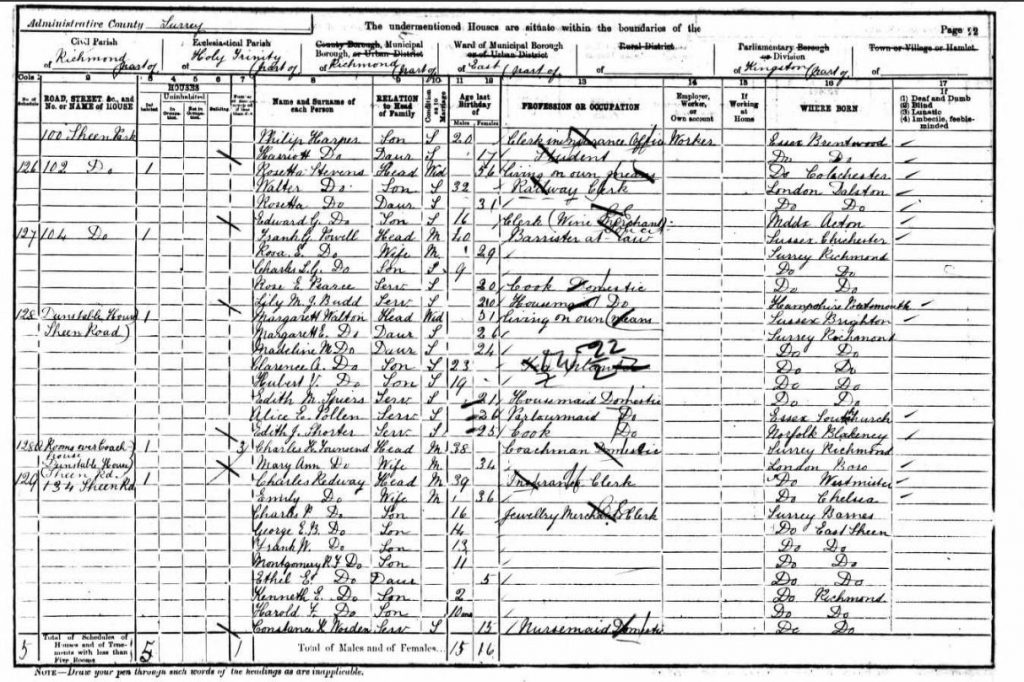

The 1901 census is interesting. Charles is still in the same job, living with his wife, six sons and a daughter, along with a domestic servant. Charles Percy is working as a Jewellery Merchant’s Clerk. They’ve moved along the road towards Richmond, though: their address is given as 134 Sheen Road (here on Google Maps, assuming the house numbers haven’t changed).

There, at the top of the same page, are Philip and Harriet Harper, and the previous page reveals that they’re the children of Thomas Etheridge Harper, who was living just round the corner from Charles Redway.

Perhaps it was Thomas who introduced Charles to Richmond Chess Club. You’d imagine they’d have got together to play chess on a regular basis, maybe, as was the habit in those days, over a glass of brandy and a fine cigar.

Over the next few years, he continued to play for Richmond on a high board, sometimes even on board 1, as well as being recorded turning up to club AGMs.

Here’s a game from the 1903 Surrey County Challenge Cup (presumably the county individual championship) against the artist Sir Wyke Bayliss. The opening was interesting: a Fried Liver Attack with an extra move for White. Black was able to play an immediate c6 so it’s not entirely clear whether or not White benefitted from the extra tempo. Anyway, Redway misplayed the attack and lost fairly quickly. (If you click on any move, a pop-up window will appear enabling you to play through the game.)

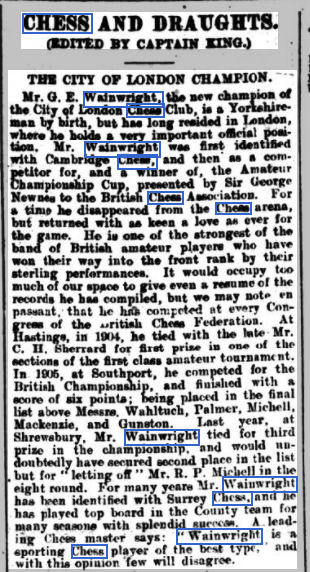

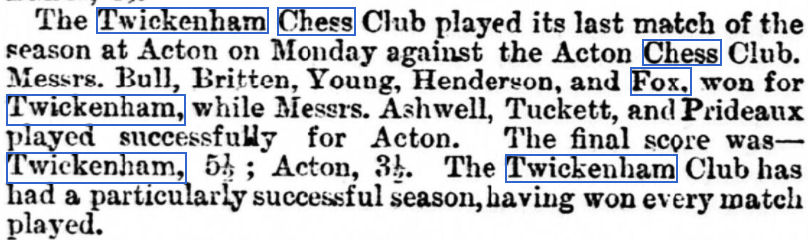

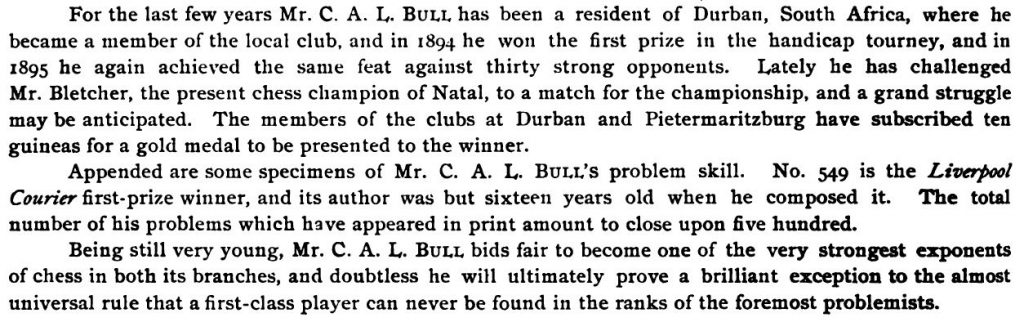

The British Championships took place for the first time in 1904, giving many amateurs the opportunity for a two week chess playing summer holiday. Charles took part in the First Class B tournament in Southport in 1905, scoring 4½/11, a pretty respectable result. He tried again at Tunbridge Wells in 1908, but his result in the First Class A tournament was a disappointing 2½/11. (Note that the A and B tournaments were parallel and of the same strength.) To be fair, this was a pretty strong tournament: the winner was Georg Schories, a German master resident in England who wasn’t eligible for the championship, and the young Fred Dewhirst Yates shared 4th place.

Earlier in 1908, Charles had taken part in a simultaneous display at Surbiton Chess Club against World Champion Emanuel Lasker, emerging with a highly creditable draw.

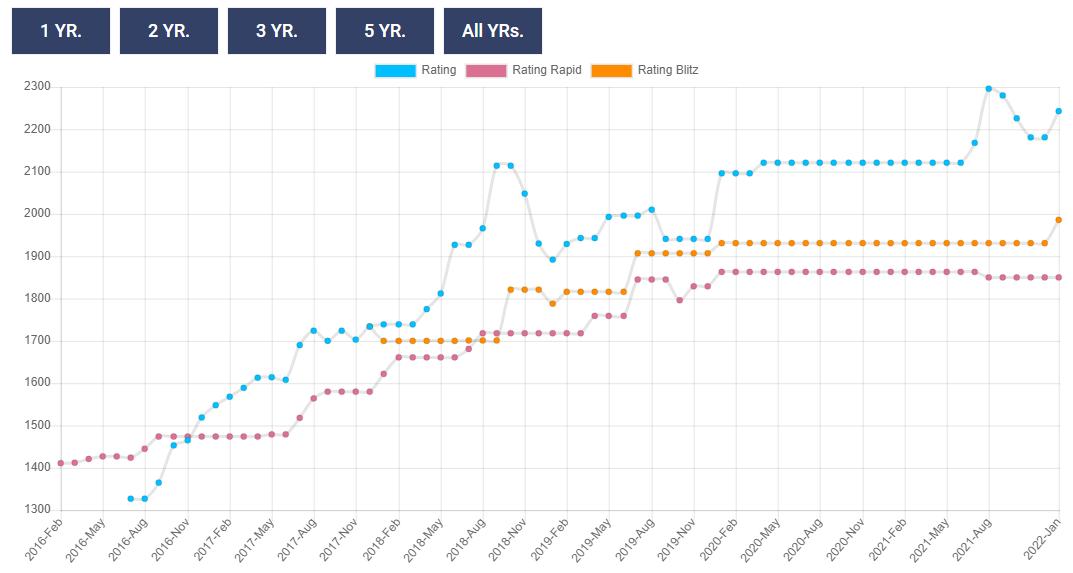

EdoChess estimates his rating as round about 2000: a strong club player but not of master standard.

One of their sons, Montague, had died in his teens in 1906, and, the following year, the family moved to Dryburgh Road, Putney, very close to Marc Bolan’s Rock Shrine. They’d remain for the rest of their lives. He continued to play up to the mid 1920s, for Ibis Chess Club in London, and in county matches for Surrey. The Ibis Chess Club was part of the Ibis Sports Club, for employees of the Prudential Assurance Company and particularly noted for its rowing. There are very few records concerning Richmond Chess Club available for this period (we should find out more once the Richmond & Twickenham Times is digitised), but perhaps he continued playing for Richmond as well.

He didn’t play in the 1912 British Championships in Richmond, but he did take part in a simul against visiting American champion Frank Marshall, winning his game.

Very little competitive chess took place during the First World War, but he returned to the board in 1919, playing in a 40-board simul against Capablanca in Thornton Heath. His club affiliation was given as Richmond rather than Putney, confirming that, in spite of moving out of the immediate area, he was still a member of Richmond Chess Club.

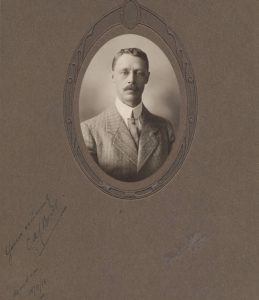

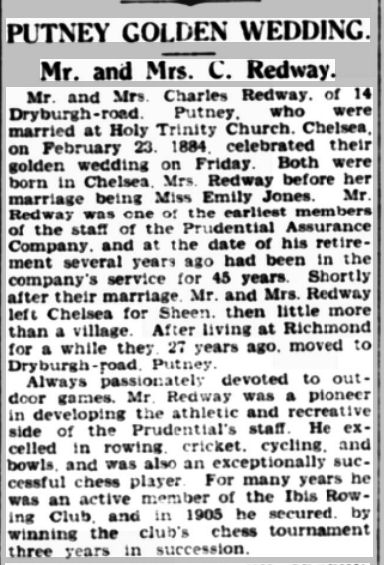

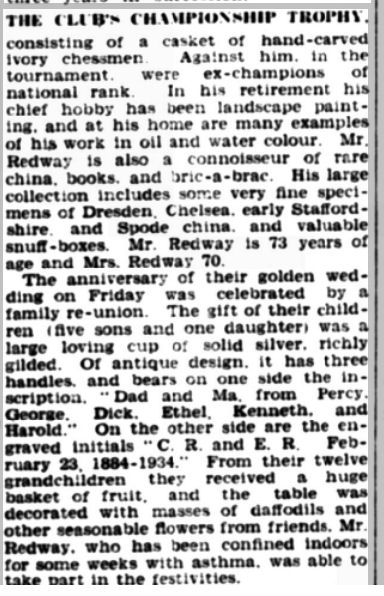

In 1934, with their family name now famous in Whitton, Charles and Emily celebrated their Golden Wedding. The report in the local press provides some interesting detail about Charles’s wide range of interests.

It’s sad that Charles was unable to take part in the festivities. He died just over a year later, on 7 March 1935. Emily survived another 21 years, into her 90s, outliving four of her sons and remaining at home until the end.

Charles wasn’t the only one of his siblings interested in chess, although he appears to have been the only active player.

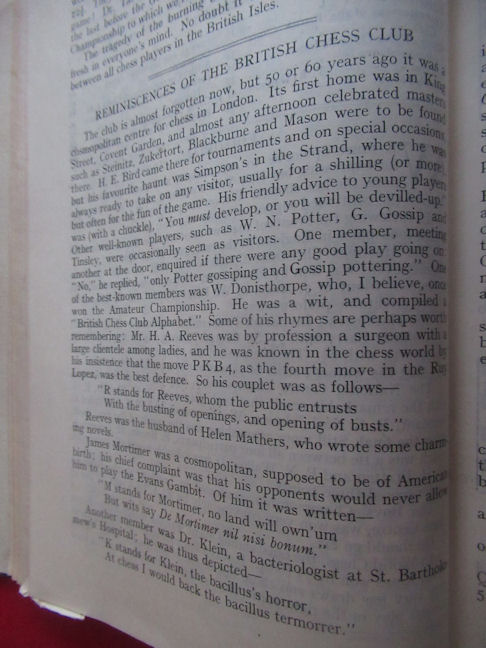

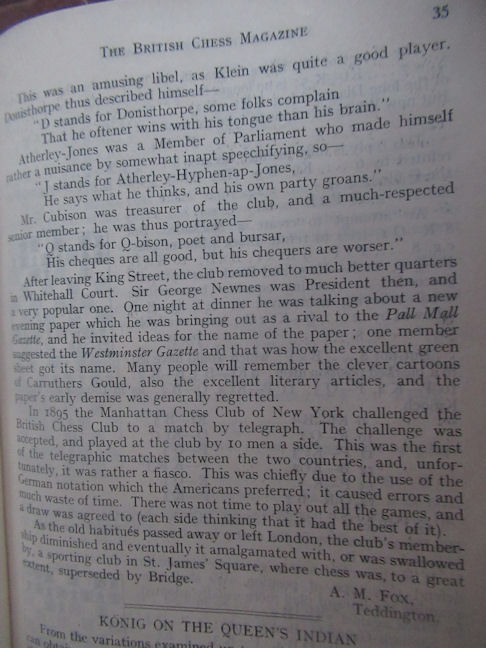

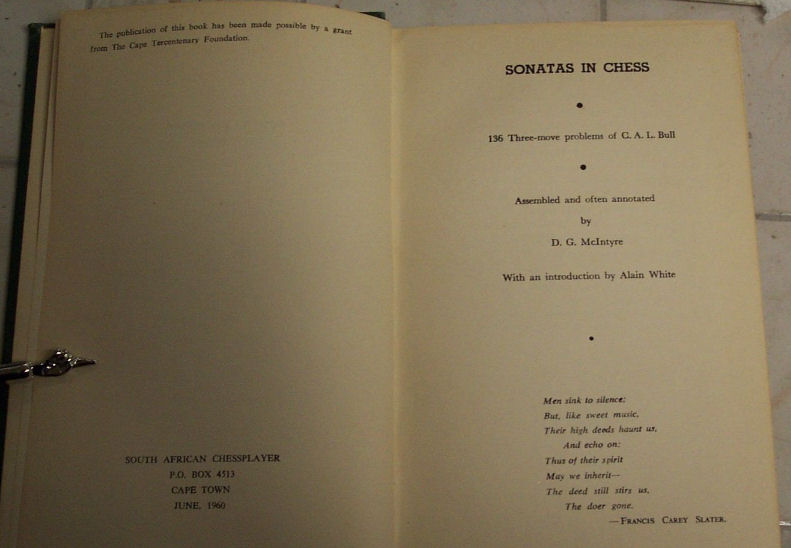

Readers of a certain age may recall a London chess book shop called Frank Hollings. One of Charles’s brothers, William Edward Redway (1865-1946), ran the business for about 40 years until his death, selling and occasionally publishing chess books. Edward Winter provides some information in this fascinating article.

Another brother, George William Redway (1859-1934), was also a bookseller and publisher, specialising in books on the occult. An announcement was made in 1895 that he was going to publish Lasker’s book Common Sense in Chess, but the arrangement, if indeed there was one, seems to have fallen through. The American edition was published by the New Amsterdam Book Company in 1895 and the European edition jointly by Bellairs & Co London, Mayer & Müller Berlin and the British Chess Company the following year.

You might wonder whether any current residents of Redway Drive are aware of the Redway family and their chess connections. Perhaps two of them are: when visiting the Chess Palace a few years ago, noted chess historian Jimmy Adams told me that his sister and her husband lived in Redway Drive (her husband is a rugby fan and wanted to be near Twickenham Stadium).

Here’s what the road looks like in 2022.

It’s a bit different, 90 years on from the photograph at the beginning of this article.

Here you have it – the road, and estate, named after Charles Percy Redway, whose father was one of our great predecessors in the early years of Richmond Chess Club. Join me again soon for some more Richmond Chess Club members from the first decade of the last century.

Acknowledgements and sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

‘Whitton Memories’ Facebook group

Wikipedia

Twickenham Museum website

britainfromabove.org.uk

chessgames.com

BritBase

EdoChess

Chess Notes (Edward Winter)

Lyrics from At the Zoo (Paul Simon)