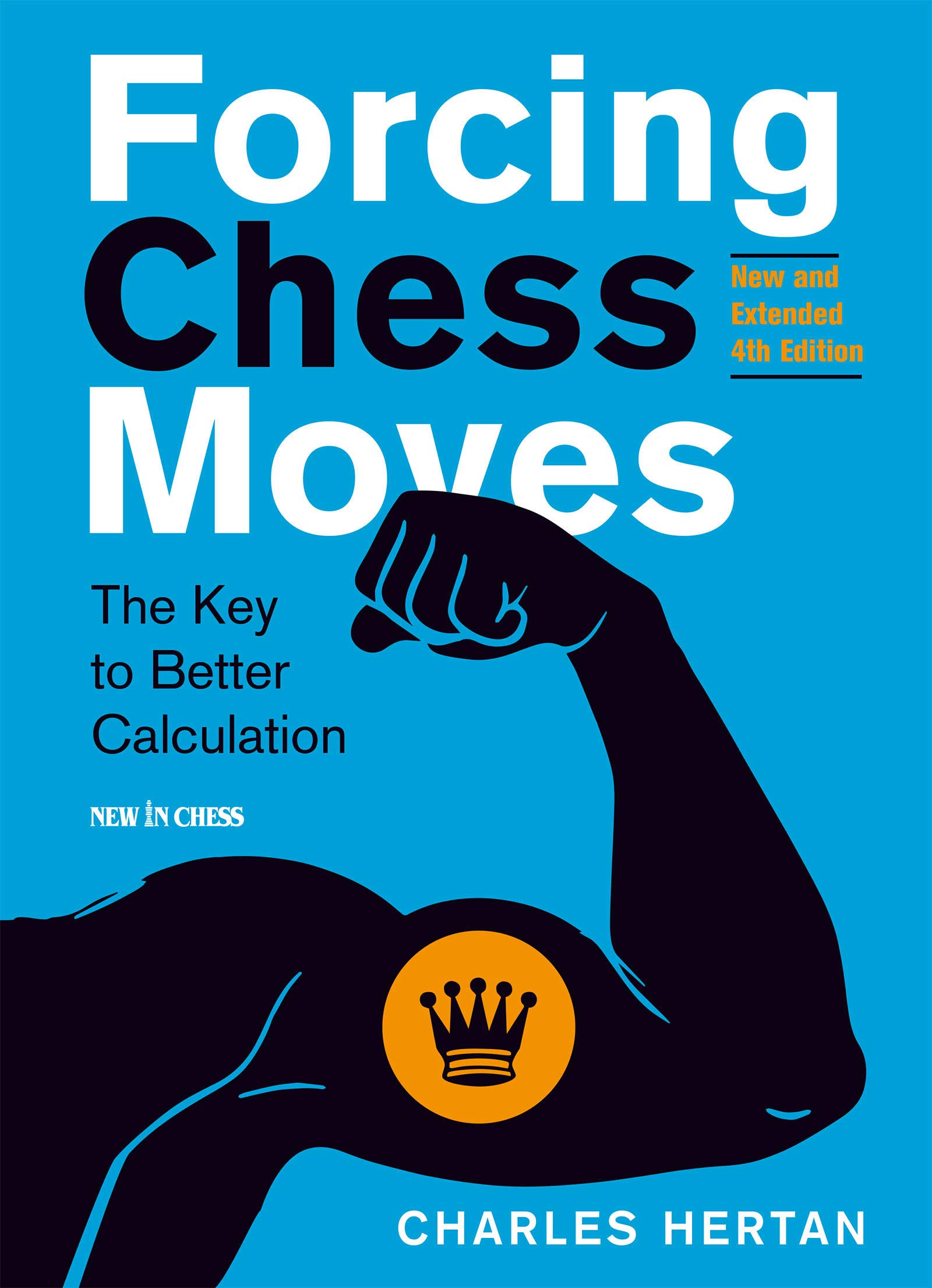

Forcing Chess Moves : The Key to Better Calculation : Charles Hertan

From the publisher :

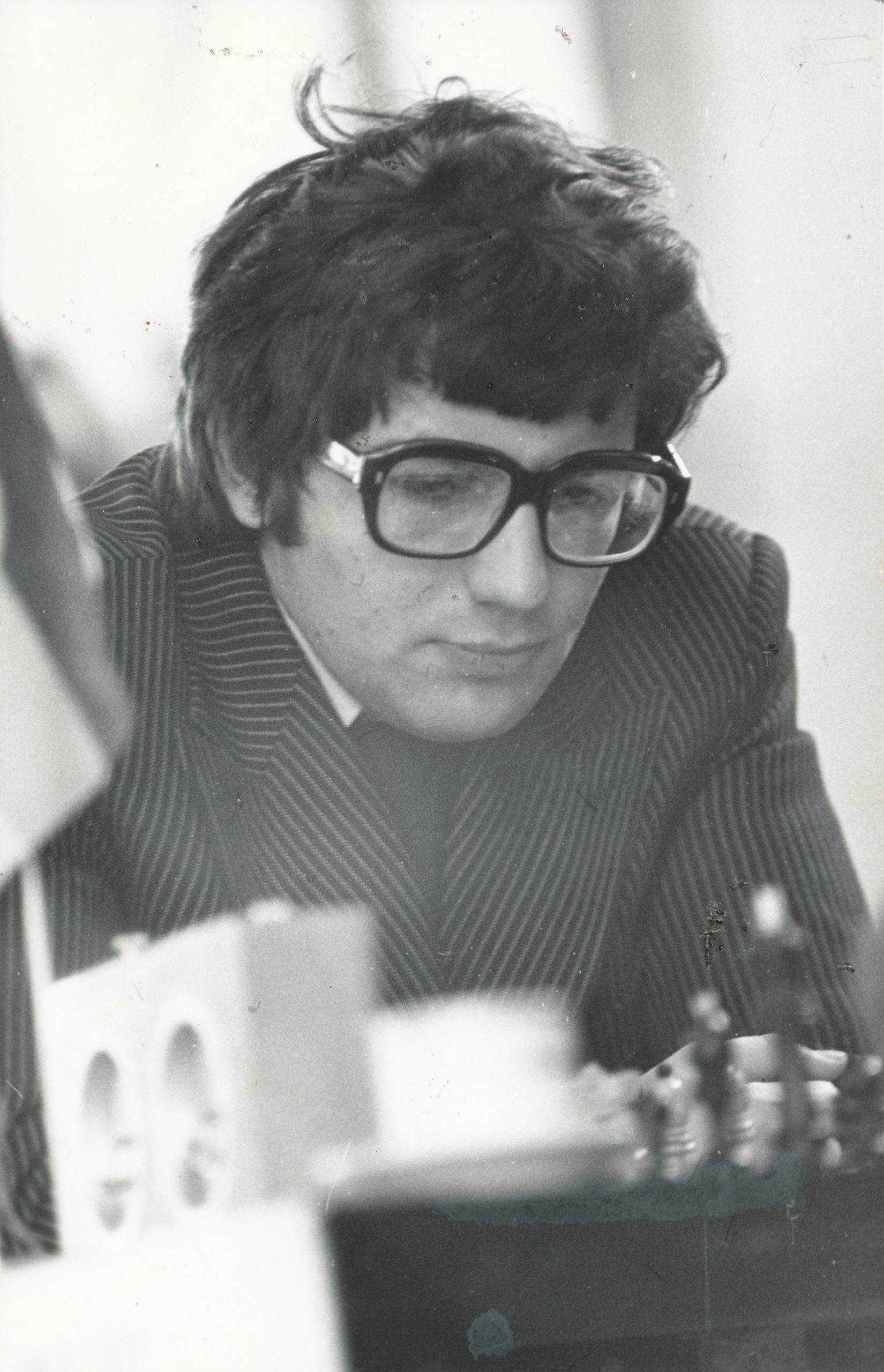

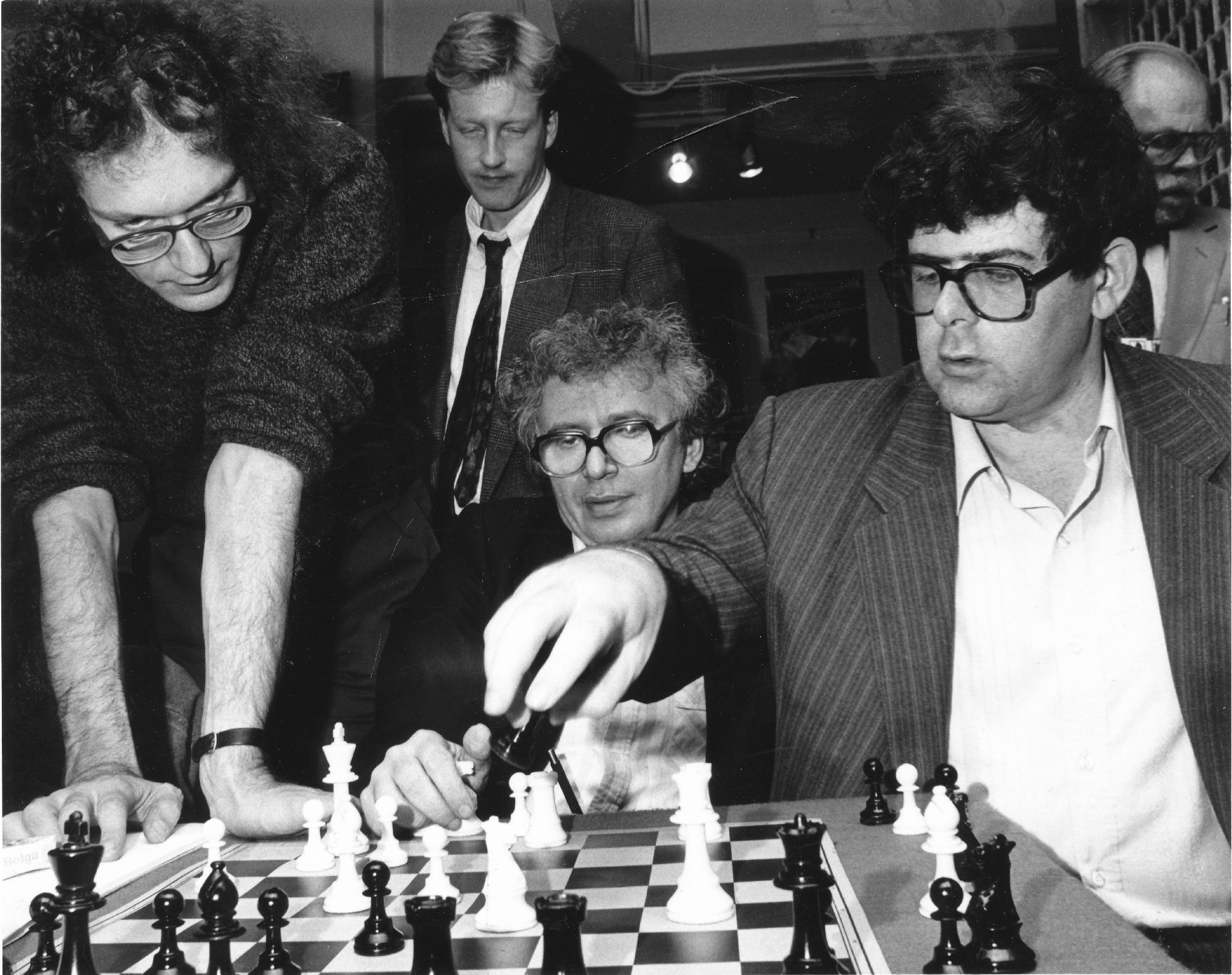

“Charles Hertan is a FIDE master from Massachusetts with several decades of experience as a chess coach. He is the author of the bestselling Power Chess for Kids series. Joel Benjamin broke Bobby Fischer’s record as the youngest ever US master. He won the US Championship three times and has been a trainer for more than two decades. His book Liquidation on the Chess Board won the 2015 Best Book Award of the Chess Journalists of America (CJA). His latest book is the highly acclaimed Better Thinking, Better Chess.”

From the book’s rear cover :

“Why is it that the human brain so often refuses to consider winning chess tactics? Every chess fan marvels at the wonderful combinations with which famous masters win their games. How do they find those fantastic moves? Do they have special vision? And why do computers outwit us tactically? Forcing Chess Moves proposes a revolutionary method for finding winning moves.

Charles Hertan has made an astonishing discovery: the failure to consider key moves is often due to human bias. Your brain tends to disregard many winning moves because they are counter-intuitive or look unnatural. Its a fact of life: computers outdo us humans when it comes to tactical vision and brute force calculation. So why not learn from them? Charles Hertan’s radically different approach is: use COMPUTER EYES and always look for the most forcing move first.

By studying forcing sequences according to Hertan’s method you will: Develop analytical precision; Improve your tactical vision; Overcome human bias and staleness; Enjoy the calculation of difficult positions; Win more games by recognizing moves that matter. This New and Extended Fourth Edition of Hertan’s award-winning modern classic includes 50 extra pages with new and instructive combinations.

There is a foreword by three-time US chess champion Joel Benjamin, and a special foreword to this new edition by Swedish Grandmaster Pontus Carlsson. Charles Hertan is a FIDE master from Massachusetts with several decades of experience as a chess coach. He is the author of the bestselling Power Chess for Kids series.”

You might think a chess puzzle book is just that, but there are many ways of going about it.

Are you going to write a text book or an exercise book? Or perhaps a text book with exercises to reinforce the lessons in the text?

Are you going to deal with puzzles winning material, checkmate puzzles, or perhaps positional sacrifices?

Are you going to provide practical advice to your readers about how to find tactics in their own games, or are you simply content to let the positions you demonstrate serve as an inspiration?

How are you going to order it? By tactical device? By level of difficulty? By pieces sacrificed? By squares on which sacrifices are played? Alphabetically: by player? Chronologically: by date?

What level are you aiming it at? Novices? Club players? Experts? Masters?

Most importantly, perhaps, what’s your USP? How are you going to stand out from the crowd?

This is the fourth edition, so Charles Hertan’s book has certainly proved popular (I’d previously read the first edition) and rightly so as well. Everyone enjoys a good puzzle book and this is one of the best on the market.

Let’s take a look inside.

Chapter 1 is about Stock Forcing Moves.

It’s immediately clear that readers should already be very familiar with basic tactical ideas: forks, pins, discovered attacks, deflections and so on. They should also be aware of the concept of what Hertan calls Stock ideas: common ideas which you will gradually become aware of as you look at more and more tactical exercises.

So it’s very much a book for club standard players rather than a book for novices.

This, for example is a common idea. White won with 1. Rxf7+!! Rxf7 2. Qxh6+!! Kg8 3. Qh8+! when White emerges two pawns up (Gallagher – Curran Lyon 1993).

At the end of every chapter you’ll find some puzzles to test your growing tactical skills.

Chapter 2 moves onto Stock Mating Attacks . The same sort of thing, but this time we’re mating our opponents rather than just winning material.

Chapter 3 is Brute Force Combinations. Hertan rightly observes that tactical skill combines two elements, depth and breadth of vision, a point missed by many authors and teachers. This chapter is about depth of vision. “Accurate brute force analysis”, according to the author, “is the single most important chess skill”. I wouldn’t disagree: I’d just add that you will often need to be able to assess the final position accurately: analysis = calculation + assessment.

This is where things start getting difficult.

A typical example.

Here’s Hertan’s commentary on the conclusion of Alatortsev – Boleslavsky (Moscow 1950).

“Black is able to parlay a fleeting advantage in activity into a stunning brute force win:

1… Bh3! 2. f4!

The natural 2. Rfe1 fails to 2… Rxf2! 3. Kxf2 Qe3#.

2… Bxf1!!

Since 2… Qc5 3. Rf2 holds, Black had to seek a creative solution, maintaining the initiative.

3. fxg5 Rxe2 4. Qc3 Bg2! 5. Qd3

There’s no time for 5. Re1 Bh3! and, at the right moment, … Rxe1+ and Rf1+! with a winning ending.

5… Bf3!

Not 5… Rff2 6. Re1!.

6. Rf1

White has no good answer to 6… Rg2+, e.g. 6. Kf1 Rxh2; or 6. Qd4 Rg2+ 7. Kf1 c5 8. Qxd6 Bc6+ 9. Ke1 Rg1+ 10. Ke2 Rxa1 11. Qe6+ Rf7.

6… Rg2+ 7. Kh1 Bc6!

A beautiful quiet forcing move; not 7… Rd2? 8. Rxf3 with drawing chances.

8. Rxf8+ Kxf8 9. Qf1+ Rf2+ 0-1”

You’ll see that some of the examples aren’t easy to solve from the diagram. You need what Hertan calls excellent ‘computer eyes’ to calculate accurately that far ahead.

The remainder of the book is devoted to improving your move selection by overcoming human bias. The point is sometimes made that the difference between experts and masters is not so much that they think further ahead, or that they consider more moves, but that they consider better moves. Hertan believes that we often miss the best moves because of cognitive bias. Computers, of course, don’t have this problem.

Chapter 4 looks at Surprise Forcing Moves. These fall into two categories: moves that look impossible and moves that appear unusual or antipositional.

This is from Vetemaa – Shabalov (Haapsalu 1986).

Here, Black found the ‘impossible’ 1… Qb5!!, leaving the queen en prise to two pieces, but spotting that, if either piece takes, the other is pinned so 2… Nb3 is mate.

White has to prevent Qb2# and 2. b4 loses to Nb3+. The game continued 2. Rd2 Nxc3 3. Qxc3 Nxb3+ 0-1.

Chapter 5 is about ESTs: Equal or Stronger Threats. When your opponent makes a threat it’s natural only to consider defensive moves. Sometimes your best option will be to create an equal or stronger threat, but cognitive bias makes these moves hard to find.

Chapter 6 looks for Quiet Forcing Moves, which are again easy to miss. I’m not sure that I’d call a move threatening mate ‘quiet’, though. I guess it all depends what you mean by the word.

Chapter 7 brings us onto Forcing Retreats. Again, when you’re attacking, human bias tend to lead you towards looking at forward rather than backward moves.

From Filguth – De la Garza (Mexico 1980):

“Are your computer eyes sufficiently trained to find the wondrous shot 1. Qh1!! and the two brute force variations that make it the strongest attacking move on the board?”

1… Qh5 would be met by g4 as the h-pawn is guarded, while 1… Qf6, the move played over the board, was met by 2. Bg5! 1-0 because, after 2… hxg5 hxg5, the white queen breaks through to h7.

You’ll realise at this point that there’s considerable overlap between chapters: Qh1 might be seen as a Surprise Forcing Move or a Quiet Forcing Move as well as a Forcing Retreat.

Chapter 8 offers Zwischenzugs: intermediate moves in which, instead of playing an automatic recapture, you find something stronger to do first. There are similarities here with ESTs here: again, human bias will lead you towards taking back without stopping to think about it.

Defensive Forcing Moves are the subject of Chapter 9: these might be moves using tactical force to refute a dangerous but unsound attack, or counterattacking moves, where the defender suddenly turns into the attacker.

Chapter 10 brings us to Endgame Forcing Moves, although Hertan’s definition of endgame is not the same as mine, including, as it does, positions where each side has queen, rook and minor piece.

Chapter 11, Intuition and Creativity, sums everything up. According to Hertan there are five factors which will enable you to develop master intuition: a strong knowledge of stock tactics, hard work in calculating variations, creativity, courage and practical experience and wisdom.

Chapter 12 is a final set of exercises, and Chapter 13 gives you the Hertan Hierarchy, a tool for teaching better calculation skills, which you might see as a flowchart to help you find the best move.

This isn’t the only way to write about tactics, and I’m not convinced that Hertan’s methods are as revolutionary as the publisher claims. Teaching students to look for checks, captures and threats dates back, I think, to Reinfeld and Purdy in the 1930s. I’ve always taught my pupils to use a CCTV to look at the board: look for Checks, Captures, Threats and Violent moves. What he adds, and I’m not sure how original this is, and whether it’s any more than common sense, is to advise you to analyse the most forcing moves first, no matter how foolish they might appear. The idea of using protocols to find the best move and avoid missing tactics dates back at least to Kotov in Think Like a Grandmaster. Some players, including this reviewer, find protocols helpful in some situations, but others strongly dislike the whole idea.

You might also find the continual repetition of the phrase ‘Computer Eyes’ rather grating, and the language at times over hyperbolic. On the other hand, many readers like this style of writing.

But everyone loves tactics books full of beautiful, surprising, creative and imaginative moves, and this book is perhaps the best on the market in that respect. The author has spent decades collecting positions of this nature, and his experience and enthusiasm shines through every page.

It’s not a book for novices. You need a basic grounding in tactics and thinking skills, along with the understanding that most tactics don’t involve sacrifices or surprise moves, that most sacrifices you’ll consider in your games will be unsound, and that, at least at amateur level, more games are lost by unsound sacrifices than won by sound sacrifices (although many games at all levels are won by unsound sacrifices). But anyone from, say, 1400 or so upwards, will be enchanted and inspired by the hundreds of examples of spectacular play to be found here. They’ll also enjoy the exercises and find at least some of the advice, particularly, perhaps, about avoiding cognitive bias when selecting moves to analyse, helpful.

While the teaching methods might not suit all readers, you won’t be disappointed by the contents.

Richard James, Twickenham 1st December 2020

Book Details :

- Paperback : 432 pages

- Publisher: New In chess; New and Extended 4th ed. edition (16 Aug. 2019)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 9056918567

- ISBN-13: 978-9056918569

- Product Dimensions : 16.94 x 2.77 x 23.67 cm

Official web site of New in Chess