The chess players of Richmond and Twickenham had more than two decade to wait before another club arose in their area.

A chess club in Twickenham opened its doors for the first time, probably in Autumn 1880. This is the first of a series of articles looking at some of their members between 1881 and 1906.

I should point out here that there will probably be a lot more information available online once the Richmond & Twickenham Times is digitised. I’m not the only local historian who’s been waiting years for this. But we still have quite a lot of information about who their members were and what they did, both at the board and in the rest of their lives. A pretty interesting bunch they were as well, with some even more interesting relations.

The early 1880s were times of great change in the English chess world. Over the next couple of decades chess clubs would be transformed from somewhere for gentlemen to play their friends over a glass of brandy and a fine cigar to something resembling the evening chess clubs we know today, competing in leagues against other clubs in the vicinity. One early sign of change was the foundation of the British Chess Magazine in 1881.

It’s in the first volume that we find the first readily available mention of the new Twickenham Chess Club.

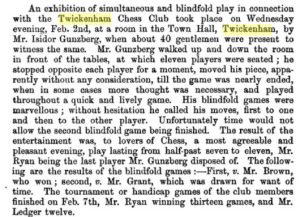

We have a report of a simultaneous display by Isidor Gunzberg (sic), an up and coming London-based Hungarian, who, within a few years, would be considered one of the world’s strongest players.

It was quite impressive, I guess, for a new club to welcome such an illustrious guest.

Simultaneous displays were very popular at the time, and so were handicap tournaments, in which stronger players would give a material handicap to their weaker clubmates.

We read that Mr Ryan, who would be a significant figure in the story of Twickenham Chess Club, won the handicap tournament and was also the last to finish against Gunsberg.

We need to find out more about him.

When I’m travelling by bus to the Roebuck, I usually take the 481 to Princes Road, Teddington, from where it’s a 10 minute walk, passing, if I choose, the residence of GM Daniel King, to reach the former venue of Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club.

As I turn into Princes Road I pass this rather impressive residence at No. 1: it was previously known as Fulwell House.

Let’s knock on the door and see who’s at home.

We’re going to meet George Edward Norwood Ryan and his family.

George was an Irishman, born on 29 July 1825 (a day earlier and he’d have been a century and a quarter older than me) in the delightfully named village of Golden, County Tipperary, half way between Tipperary itself and the town of Cashel. The Ryans are still there now: if you visit Golden today you’ll find Eamonn Ryan Family Butcher and Conor Ryan Car Detailing. Are Eamonn and Conor related to George? Or to each other? Who knows? George was the son of Francis John Ryan, an army officer, but he would choose a different career.

His father died when he was very young, and, at some point, he moved to London where, in 1855, he married Mary Anne Wilkes. They would have a large family, seven sons, two of whom died in infancy, and five daughters.

He’s elusive in the 1851 and 1861 censuses, but in 1871 he’s living in Belgravia with his family and three servants, employed as a ‘précis writer’. Within the next year or two he moves out of the smoke to leafy Teddington, to the house pictured above.

The 1881 census tells us he’s ‘engaged on parliamentary blue books’, which are reports of proceedings in parliament, so presumably he’s writing précis of parliamentary debates for these books. A skilled job, and one which must have paid very well. And, when not engaged in his parliamentary work, he’s playing chess at the new Twickenham Chess Club.

Ryan would continue his active involvement until at least 1896, by which time two of his sons, E Ryan (probably Ernest Keating Woods Ryan rather than Edward Francis Maxwell Ryan, who had married and moved out of the immediate area) and George Norwood Ryan, were also playing. George junior would later cross the river to Kingston and change his allegiance to Surbiton Chess Club in the first decade of the 20th century. George Edward Norwood Ryan would eventually die at the age of 90, after a long and successful life, leaving effects to the value of £4224 14s.

George junior and Ernest are both of some interest. No, sadly Ernie didn’t become a milkman, and nor did Edward, under the name two-ton Ted from Teddington, drive a baker’s van. Instead, Ernest was an accountant and company secretary, who married and had two daughters. His younger daughter, Honor, married James de la Mare, a nephew of Walter, and the oldest of their three sons, another James, would marry Diana Street-Porter, sister-in-law of Janet.

Talking of Walter de la Mare, his house in Twickenham, South End House, at the end of the rather lovely Montpelier Row, is currently on the market. It’s yours for a trifling £10.5 million. Me, I think I’ll have two of them. Across the road at the other end of Montpelier Row, you’ll find, appropriately enough, the site of North End House, the home of Henry George Bohn.

George Norwood Ryan has a sadder story to tell. His marriage to Isabella Anderson would produce three sons, Lionel, Warwick and Edward, and one daughter.

Here’s Warwick:

Warwick John Norwood was the second son of George Norwood Ryan (Merchant’s Shipping Clerk) and Isabel Ryan (nee Anderson).

He became a 2nd Lieutenant 19 Dec 1914 having been a private in Inns of Court Officer Training Corps. He went to Gallipoli in October 1915 with the Dorset Yeomanry (Queens Own) and following this he continued service in the Middle East in the Imperial Camel Corps. He was reported Killed in Action 5 Sep 1916.

And here’s Edward, who lost his life just three weeks before the end of the war:

Date of Birth: –/–/1896 — Place Of Birth: Kingston-Upon-Thames — Father: George Norwood Ryan — Mother: Isabella Ryan — Siblings: Leonel Ryan, Warwick John Norwood Ryan, Isabel Ryan — Date of Death: 22/10/1918 — Cemetery: Harlebeke New British Cemetery — Rank: Captain — Service Type: Army — Battalion, sub-unit or ship: 12th Battalion — Regiment/Unit: East Surrey Regiment — Service Record: Won the Military Cross — Census Years: 1901, 1911

Source: People | Surrey in the Great War:

The citation for his award of the Military Cross:

T./iCapt. Edward St. John Norwood Ryan,

12th Bn., E. iSurr. R.

During operations on 14th October, 1918, north of Menin, he showed great gallantry and fine leadership whilst commanding a

company. He led his men forward to the final objective through a dense fog, maintaining perfect direction and touch throughout, and consolidating the position. His company captured several strong points, many prisoners, and a quantity of war material.

Source: data.pdf (thegazette.co.uk)

It’s often assumed that the upper class officers kept themselves safe while leading their lower class troops to their death. In fact:

Very large numbers of British officers were killed. Over 200 generals were killed, wounded or taken prisoner; this could only have happened in the front line. Between 1914-18, around 12% of the ordinary soldiers were killed. The figure for officers was around 17%.

Their older brother, Lionel, survived the war, and, like his father, became a ship broker. His employment with Canadian Pacific took him to Hong Kong.

He was interned by the Japanese after the fall of Hong Kong and was the 111th person to die in the Stanley Internment Camp. He died on February 27th 1945 and is buried in the Stanley Cemetery.

Source: Lionel Ernest Norwood Ryan | Christ Church, Oxford University

So George Norwood Ryan, chess player from Twickenham and Surbiton clubs, lost his two younger sons in World War 1 and his oldest son as a result of World War 2. He lived on until 1959, reaching the age of 94. His daughter also lived a long life, but, like all five of her aunts, never married. I know from personal experience that they weren’t the only unmarried sisters in Teddington.

The two Georges, father and son, were fortunate to have fought their wars over the chequered board rather than the bloody battlefield. As the Ryan family knew only too well, real wars are bad, but pretend wars are good.

We’ll be meeting George Edward Norwood Ryan again as we continue our exploration of Twickenham Chess Club in future articles.