If you walk up to the top of Richmond Hill, past one of the most famous views in the country, you’ll see an imposing edifice opposite the gate into Richmond Park.

You’ll also see it across Petersham Meadows if you walk along the Thames Path towards Ham, Teddington and Kingston.

This was, until a few years ago, the Royal Star and Garter Home for disabled former service personnel.

There was originally a hotel on the site, which closed down in 1906, and, for several years, plans for redevelopment came to nothing. The current building was constructed between 1921 and 1924 to a design by Sir Edwin Cooper based on a 1915 plan by the great and wonderful Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, providing accommodation and nursing facilities for 180 serious injured servicemen.

Most (but not all, as we’ll see) of the residents were wheelchair users as a result of injuries suffered in the First World War. In the days before parasports they were unable to access physical recreations so chess was a popular activity there. It wasn’t long before the members of Richmond Chess Club, just downhill, paid them a visit.

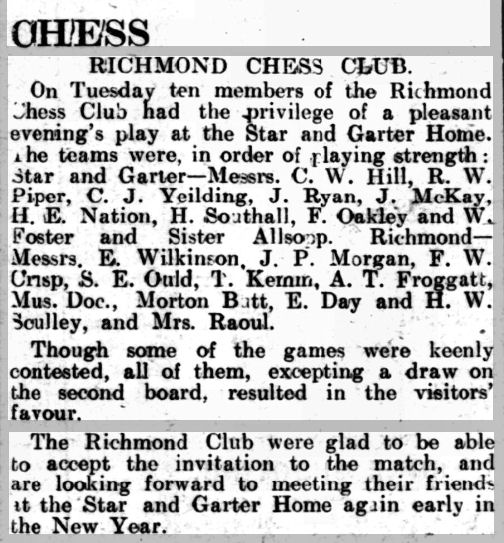

Their first match seems to have been in Spring 1926, and they returned in the Autumn.

Richmond Herald 27 November 1926

Richmond Herald 27 November 1926

It’s good to see both sides fielding a lady player: I presume Sister Allsopp was a chess playing member of the nursing staff.

This was, in effect, the club second team, but the following month their star player Wilfred Hugh Miller Kirk, visited to give a simultaneous display.

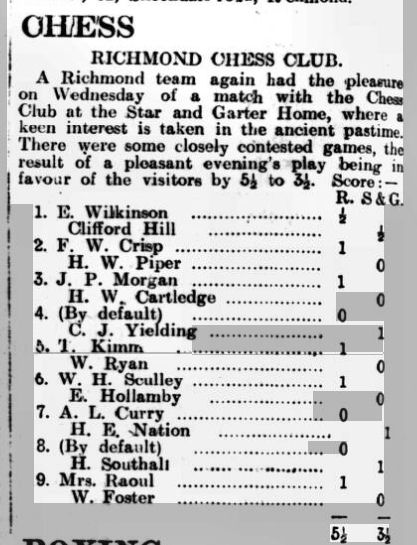

The results of their Spring 1927 match were published.

It was unfortunate (but typical for the time) that two of the Richmond visitors failed to put in an appearance. The Star and Garter top board, Clifford William Hill, did well to draw his game.

Other local chess clubs, such as the Old Richmondians, visited them for matches as well.

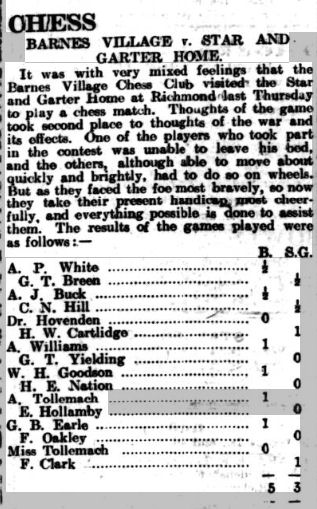

When the newly formed Barnes Village Chess Club paid their first visit they were understandably apprehensive: “Thoughts of the game took second place to thoughts of the war and its effects”. But when they got there they discovered that “as they faced the foe most bravely, so now they take their present handicap most cheerfully”.

Clifford Hill seems to have been a pretty strong player who rarely lost in these matches.

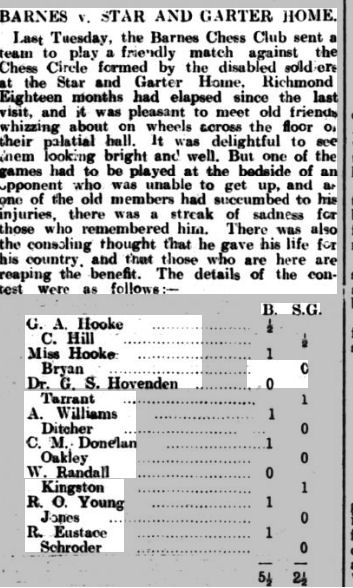

In 1931 he even secured a draw against the more than useful Barnes Village top board George Archer Hooke.

Perhaps we should find out more about him.

Clifford William Hill, known to his friends as Tony, was born (as William Clifford Hill) on 27 October 1898 in Brierley Hill, Staffordshire, an industrial town in the Black Country best known for its glass and steel works. His father, Horace Emmanuel Holloway Hill, was employed by one of the local ironworks before becoming a railway platelayer and then a gas fitter. A very different background, to be sure, from the middle class gentlemen he would have encountered in his matches against Richmond and Barnes Village chess clubs.

I can’t find any very obvious WW1 service records for him, nor can I locate him in the 1921 census. Secondary sources claim he signed up at the age of 17, was severely wounded at the Battle of the Somme, and spent time in a number of hospitals.

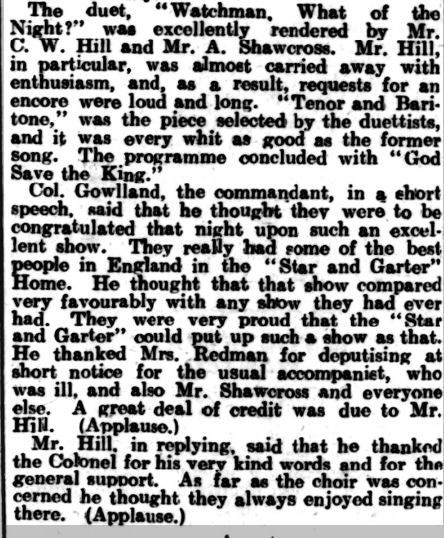

It turns out he was a rather remarkable man. Not only a more than competent chess player, but the editor of the Star and Garter Magazine and a multi-talented musician as well: singer (both alto and tenor), violinist and conductor.

Here he is, arranging, conducting and performing at a concert party.

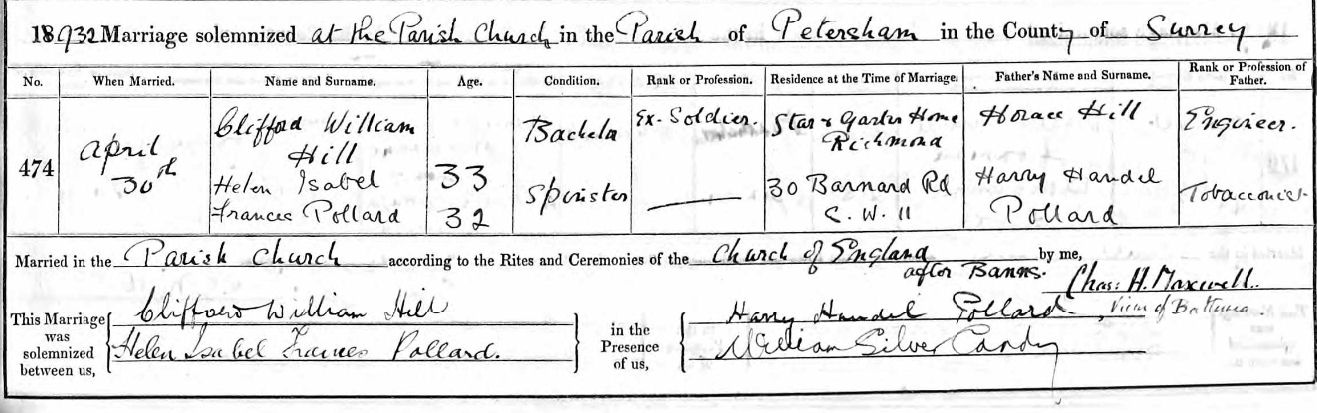

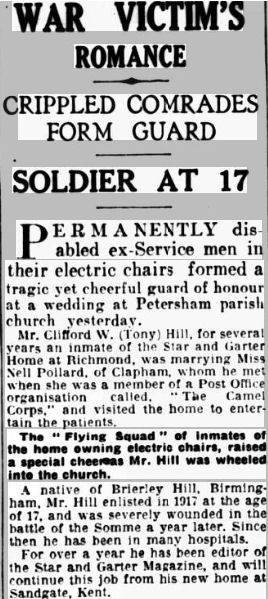

One of the many organisations providing entertainment to the residents was a Post Office group called the Camel Corps. One of their members, Helen Isabel Frances (Nell) Pollard, was smitten, and in 1932 they tied the knot in nearby Petersham.

Nell’s father’s middle name suggests a family interest in music, doesn’t it?

According to this article, they were moving to Sandgate, near Folkestone, where the Star and Garter had a seaside branch. It also appeared to mark the end of his chess career: his last mention seems to be earlier that year.

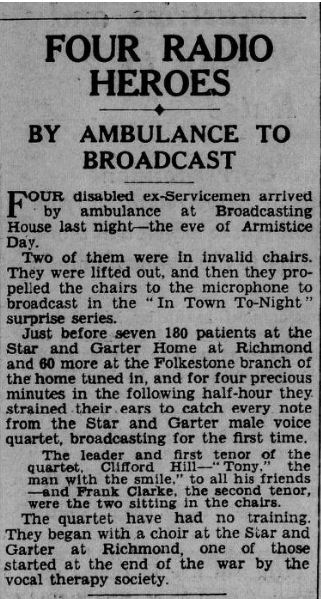

In 1934 Clifford (or should we call him Tony) and his friends achieved national prominence when they appeared on the wireless.

Tony, the man with the smile. How wonderful!

The 1939 Register found Tony and Nell in Brierley Hill with his parents, but by the time of the 1945 Electoral Roll they’d moved to Sir Oswald Stoll Mansions in Fulham a block of mansion flats right next to Chelsea FC providing supported living for disabled former service personnel.

Clifford William Hill died back at the Star and Garter on 13 March 1952, at the age of 53. A remarkable man from a very modest background who, despite being confined to a wheelchair, achieved much in his life. He would have been a popular and important figure in the Star and Garter, and deserves to be remembered today, not only as the man with the smile. I’m sure chess, along with music, and, of course, Nell, brought him much satisfaction.

By the time he’d moved on, another highly competent chess player had moved in. You can see him back in that 1931 team list. Step forward Reginald Aubrey Tarrant.

Reginald was very different. Unlike most of the residents, he had been too young to serve in the war, and he was in the Star and Garter through illness rather than injury.

He was born on 12 May 1909 in Banbury, Oxfordshire, the second son of Francis Llewellyn Tarrant and Ethel Agnes Best, but by 1911 the family had moved to Acton where his father was working as an oil merchant. This was a family which would have both problems and tragedies to contend with.

In 1912 their third son, Francis Llewellyn junior was born, but only survived a few months. The following year, their oldest son, Hugh Gordon Tarrant, aged 6, was knocked down and killed by a car. Reggie and Gordon were sitting on stones marking the boundary between Ealing, Acton and Brentford. A car travelling at an excessive speed swerved to avoid a horse and cart, and hit the two boys, killing Gordon and seriously injuring Reggie. The coroner’s court recorded a verdict of manslaughter and the driver was sent for trial at the Old Bailey, but at this subsequent trial he was cleared of all charges, one would imagine much to the parents’ distress.

Having lost two sons, one to a tragic accident which left their third son seriously injured, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Francis and Ethel’s marriage hit problems. By 1916 Francis had moved to Southsea, where he ran a business as a motor engineer and driving instructor, which, he claimed, exempted him from military service. Ethel was back in Ealing claiming maintenance arrears. Perhaps they got back together as a daughter, Dorothy May, was born in 1918 (or perhaps he wasn’t her father). But in 1921 Ethel was again claiming maintenance, while Francis made a counter claim on the grounds of her alleged adultery.

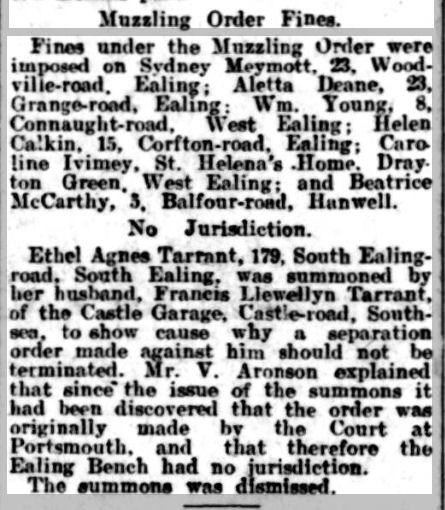

And just look who else was up before the magistrates at the same time. None other than Ealing Chess Club Treasurer Sydney Meymott, fined for not having his dog muzzled.

Meanwhile the 1921 census found Francis still in Southsea, apparently married to Florence May Tarrant (he’d later be ‘married’ to Harriet Grace Tarrant). Dorothy, although not yet three years old, seemed to be boarding at St Ethelburga’s convent school/orphanage in Walmer, Kent (the other pupils were aged between 5 and 19), with the census record claiming, incorrectly, that her father was dead. I haven’t been able to find a record for Ethel.

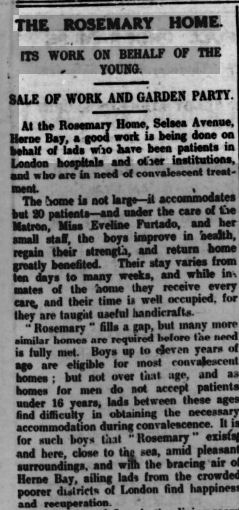

Reggie was a boarder at the Rosemary Home in Herne Bay, Kent. This was an outdoor convalescent home for boys, which suggests to me that he might possibly have had tuberculosis.

He made a good recovery, and in 1924, at the age of 15, joined the Royal Navy as an Arethusa Boy, where he trained as a telegraphist. He might well be one of the cadets in this film.

In 1928 he suffered a serious illness (heat stroke) and on 18 June 1930 he was invalided out due to organic heart disease. This must have been so severe that he was unable to live independently. It was at this point, or shortly afterwards, that he moved into the Star and Garter, where he rapidly became one of their strongest chess players. Did he learn chess there, or did he already know how to play?

By 1931, as we’ve seen, he was playing in the Star and Garter chess team, and he was soon invited to join Richmond Chess Club. It would be interesting to know how he travelled there. He was a decade or more younger than most of the other residents, and, also unlike them, probably not a wheelchair user. Walking downhill into the town centre might not have been a problem, but walking back up to the top of Richmond Hill might not be a good idea if you’re suffering from organic heart disease. Perhaps someone gave him a lift.

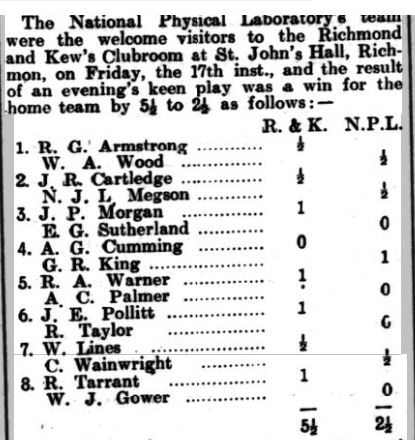

Here he is, in 1933, playing on bottom board against the NPL.

He was now making rapid progress. In the 1933-34 club championship he shared first place in his section with Wilfred Kirk, only losing the tie-break game, and also finished 3rd in the handicap tournament.

Tarrant continued to advance in the ranks, and by 1936 he was regularly playing on third board behind Wilfred Kirk and Ronald George Armstrong: I’d guess he was by now about 2000 strength: a strong club player.

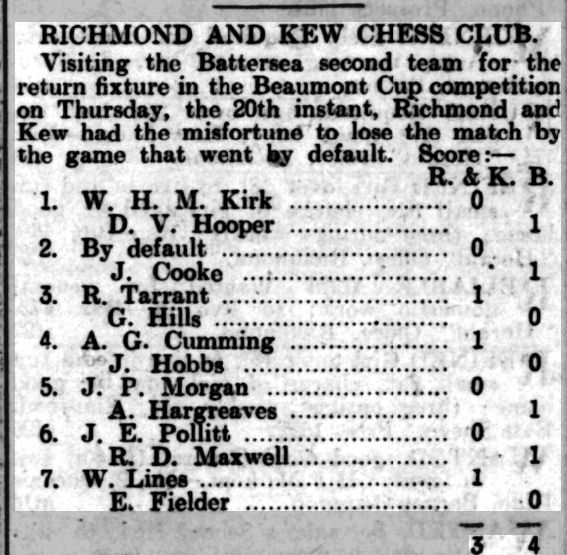

In this Beaumont Cup (then as now, the Surrey Second Division) match Armstrong presumably failed to turn up, while Kirk faced an interesting young oponent on top board.

David Hooper later became a distinguished writer and historian of the game, best known for co-authoring The Oxford Companion to Chess with Ken Whyld.

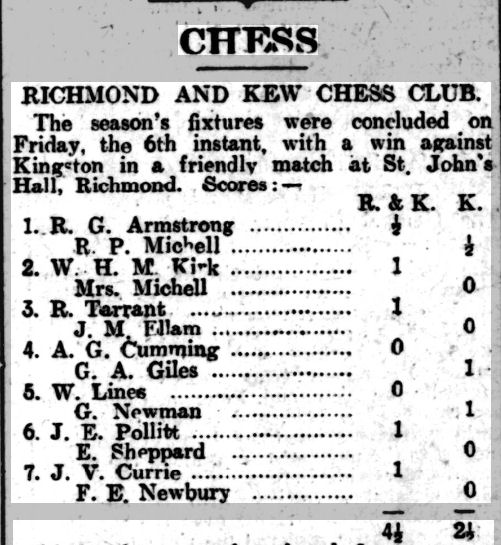

A couple of weeks later Richmond did well to win a friendly match against a strong Kingston team headed by Mr & Mrs Michell.

James Mcewen Ellam (1882-1965) would, a decade or so later, be one of the leading lights responsible for founding the Thames Valley Chess League. For many years a competition was held at the start of every season for a trophy named in his honour.

That season Reginald Tarrant (was he still known as Reggie, I wonder?) won both the handicap tournament and match prize (presumably for the best results in club matches: this was a pocket chessboard presented by the Surrey County Chess Association) as well as finishing half a point behind Kirk and Guy Fothergill in the club championship. He was also elected onto the committee at the 1936 AGM. When Kirk moved away in 1937, Tarrant now found himself on board 2 in club matches.

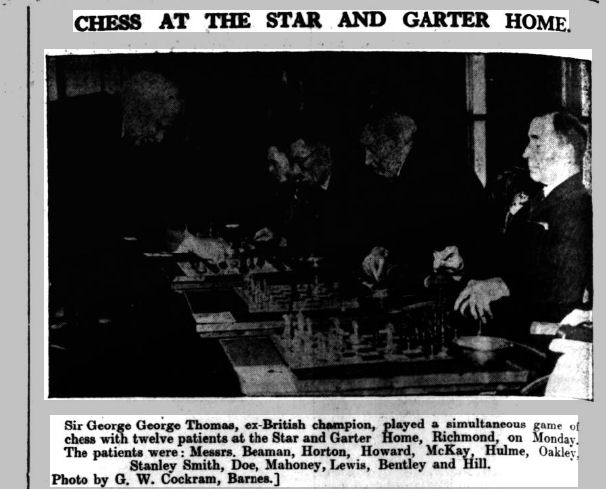

However, he wasn’t among the opposition when Sir George Thomas visited the Star and Garter to give a simul.

(Sir George George Thomas? So good they named him twice?)

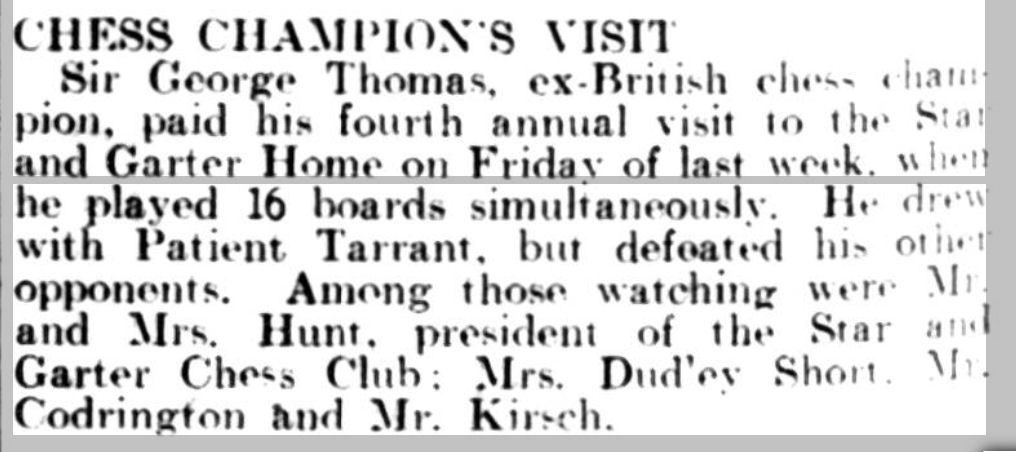

But when war broke out again, Richmond Chess Club, with an ageing membership, decided to close its doors for the duration. The 1939 Register recorded Tarrant in the Star and Garter, a Patient and Incapacitated: a decade or more younger than most of the other residents. He was still playing chess there. Here he is, in 1941, drawing with a famous visitor.

Mrs Dudley Short was herself a keen player: on the same page it was announced that the Richmond branch of the NCW (National Council of Women?) ran a fortnightly chess club: you could phone her if you wanted to join.

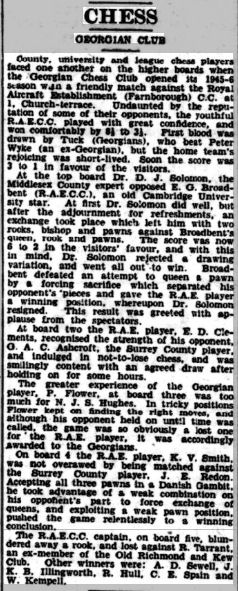

When the Second World War came to an end, a new chess club, the Georgian Chess Club, opened in Richmond. Reginald was one of its first members.

This would later become Richmond Chess Club, taking over the mantle of the ‘Old Richmond and Kew Club’, but that’s a story for another time. Reginald’s appearance here was his first, but perhaps also his last. A few months earlier he had married Peggy Dora Roberts. She’d been recorded as a Children’s Nurse in 1939 so it was quite possible that she was one of the Star and Garter nurses. I suspect that the happy couple moved in with his mother, who was living close to Kew Gardens.

Reginald and Peggy went on to have three daughters. There are birth records for Carol (1948) and Alison (1953), but, according to an old post by Carol on Genes Reunited there was another girl, Valerie. But shortly after Alison’s birth, on 4 September 1953, Reginald Aubrey Tarrant died at the age of 44.

Back at the Star and Garter, there seemed to be less interest in chess, with most local clubs closing during the war. I have a recollection of some contacts and perhaps friendly matches during the late 1960s, but chess was changing, and perhaps the Star and Garter was as well.

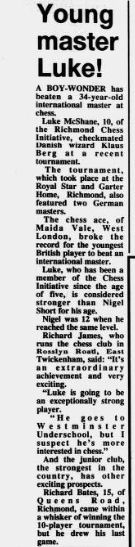

But in 1994 chess at the Star and Garter was back in the news when it hosted an international tournament as part of the Richmond Chess Initiative.

But that’s another story, which will be told in Part 4 of the history of Richmond Junior Chess Club, coming, with any luck, fairly soon.

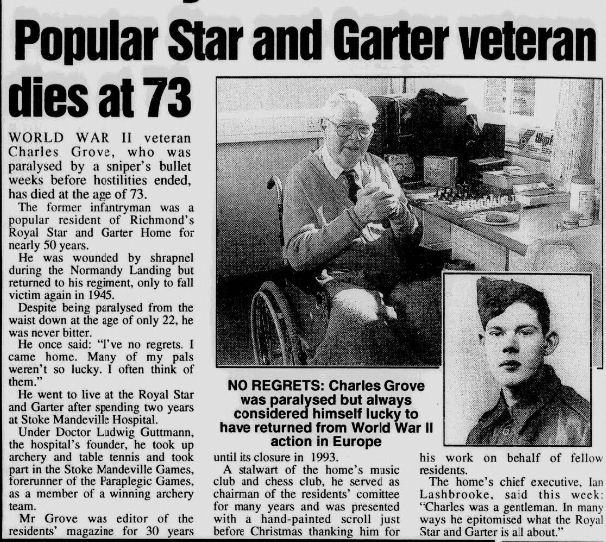

Although they were no longer playing regularly against outside clubs, chess remained popular with Star and Garter residents such as Charles Grove.

The Star and Garter home in Richmond closed several years ago and, sadly but inevitably, was converted into luxury flats. While the building had been designed specifically for wheelchair users, most of the residents were, by that time, elderly former service personnel with dementia, and the building was no longer fit for purpose. They decided their best option was to sell off the property and construct a new purpose-built home in Surbiton. You can find out more about their history here.

I’m sure both Clifford and Reginald gained much enjoyment from playing chess at the Star and Garter, and, in the latter’s case, also at Richmond Chess Club. They both had difficult lives: one, from a working class family, who was severely injured in the war, the other, from a more middle class but dysfunctional family, who was incapacitated by health problems. Chess is just as much for their likes as it is for prodigies, grandmasters and champions.

I’ve always been unhappy about the reasons given for promoting chess, on local, national and international levels. For me, we should be talking, no, shouting about the way chess can provide competition and friendship for those who are unable or unwilling to access physical sports. Richmond wasn’t the only place where, in the inter-war years, those with physical handicaps were encouraged to play chess. You’ll find out more in the next Minor Piece, which will take us to another part of the country.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archive

Wikipedia

childrenshomes.org.uk

YouTube

Star and Garter website