Last time, I introduced you to Edward Wallis, a Quaker chess player, problemist, writer and organiser from the Yorkshire seaside resort of Scarborough.

I gave you the chance to read his book 777 Chess Miniatures in Three, for which A Neave Brayshaw BA LLB provided hints for solvers. Who, I wondered, was A Neave Brayshaw?

It transpires his story is rather interesting. Like Edward Wallis he was a Scarborough Quaker, but, much more than that, he was also one of the best known Quakers of his time.

Alfred Neave Brayshaw was born on 26 December 1861, the first child of Alfred Brayshaw, a Manchester grocer, and Jane Eliza Neave. It was the custom of the time for Quaker families to intermarry, and to use surnames as Christian names. Hence, young Alfred was often referred to as Neave, and he had brothers named Stephenson and Shipley.

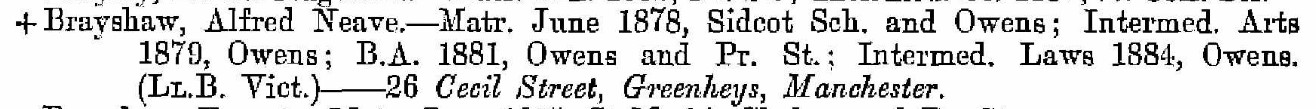

Neave was educated at Sidcot School in Somerset, and then at Owens College back home in Manchester, where he was awarded an external London University BA. He decided on a career in law, working in a solicitor’s office while continuing his studies, obtaining a Bachelor of Law degree in 1885.

He worked as a solicitor in Manchester between 1885 and 1889, while spending his evenings tutoring some of the younger students at Owens College. This experience convinced him that his real vocation was not law, but teaching, and he became an assistant master at Oliver’s Mount, a (preparatory?) Quaker boarding school in Scarborough.

It would likely have been in Quaker meetings in Scarborough that Alfred Neave Brayshaw met Edward Wallis and discovered a shared interest in chess.

Brayshaw’s particular interest was in chess problems, and his compositions were soon being published in the Illustrated London News. You can play through the solutions to the problems at the foot of this article.

Problem 1. #3 Illustrated London News 20 December 1890

Problem 2. #3 Illustrated London News 18 July 1891

In 1892 Brayshaw moved to Bootham School in York, which is still thriving today, remaining there for 11 years. Old Boys include historian AJP Taylor, farceur Brian Rix, and, briefly, drag artist Lady Bunny, along with many scions of the Rowntree family, with whom he was very much connected. Along with the Rowntrees – and Edward Wallis – he was part of the movement towards liberal Quakerism.

His next problem was a two-mover rather than a three-mover.

Problem 3. #2 Illustrated London News 27 May 1893

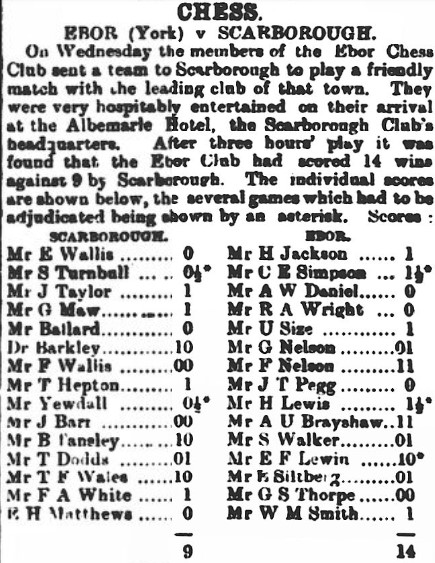

At this point, it seems that he embarked on a very short but successful career in over the board chess.

Here he is, visiting his former home town, for an away match. You’ll notice, if you’ve been paying attention, that there was a Scarborough player, CE Simpson, in the Ebor team. One wonders if Brayshaw and Wallis, perhaps along with Simpson, were involved in setting this match up.

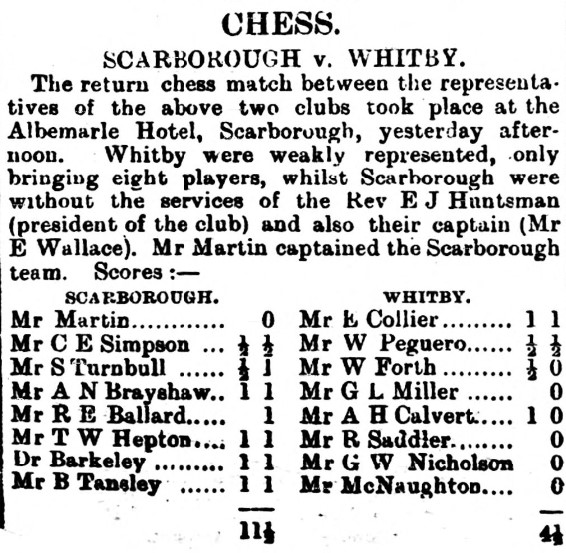

Perhaps he stayed in Scarborough for a bit: a few days later he represented them in a match against Whitby, again winning both his games.

Later that year he had a problem published in the Hackney Mercury.

Problem 4. #3 Hackney Mercury September 1894

But it seems that his brief involvement in chess playing and composition came to an end at about this time.

Alfred Neave Brayshaw remained in York until 1903, when George Cadbury established Woodbrooke, a new Quaker college in Birmingham, appointing him as a lecturer there. He still maintained his links with Bootham, though, and would do so for the rest of his life.

In 1906 he left Woodbrooke, moving back to Scarborough, re-uniting with Edward Wallis, temporarily returning to chess to help his friend with his book, to which he contributed three problems.

Problem 5. #3 777 Miniatures in Three #88

Problem 6. #3 777 Miniatures in Three #89

Problem 7. #3 777 Miniatures in Three #90

Alfred Neave Brayshaw, by this point, was working for the Society of Friends, based on the Yorkshire coast, but travelling the country lecturing on various aspects of his faith. The 1911 census found him visiting Southampton, and in 1921 he was in Chelmsford, where he would surely have lectured to some of Edward Wallis’s family friends. When he wasn’t lecturing he was writing: The Personality of George Fox was published in 1919 and The Quakers, their Story and Message in 1921, with revisions in 1927 and 1938. If you’re in the United States you can read them here.

A lifelong bachelor, from at least the end of the war onwards he was based in a central Scarborough apartment owned by Edmund (until his death) and Fanny Pearson. I wonder if he was aware that Pearson wasn’t their real name: they were actually Edmund Proctor and Fanny Anthony. After his wife disappeared Edmund had a relationship with Fanny, his housekeeper which produced three children.

In the 1920s, by now in his 60s, he also crossed the Atlantic to lecture in the United States on several occasions. He was a very busy man who probably spent little time in Scarborough.

Throughout all this time he visited Bootham School regularly to lecture to the older boys, and, every year from 1895 to 1939, broken only by the First World War, he took a party of boys from Bootham and other Quaker schools to Normandy for a summer holiday.

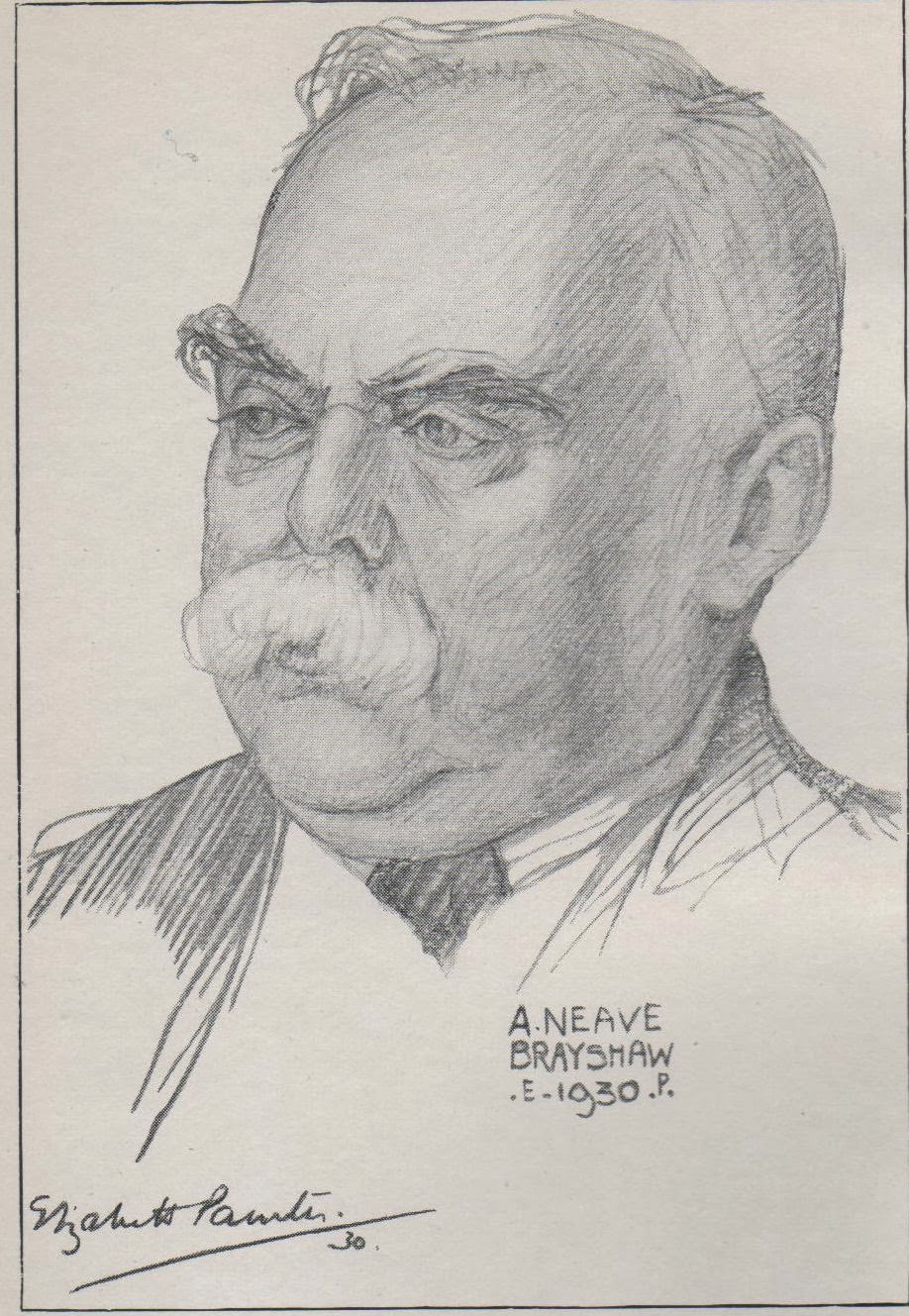

Here’s a caricature of him from 1930.

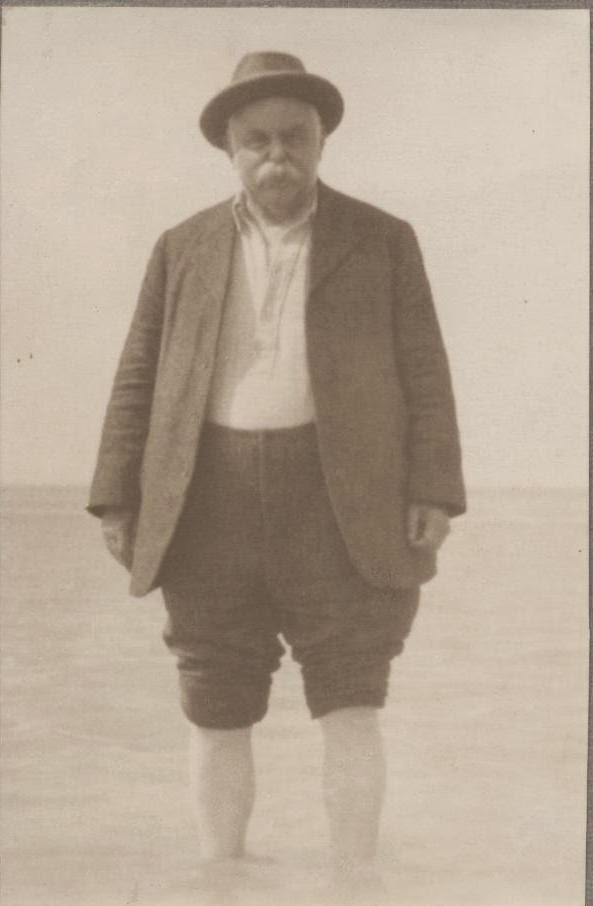

And here he is again, paddling in the sea, probably in Normandy.

By the time of the 1939 Register he was still lecturing regularly, and still living at the same address in Scarborough. But a few months later, during a blackout, he was hit by a car and died of heart failure a few days later.

30 years? More like 40 years, even if you exclude WW1. A Quaker “Mr Chips” sums him up well.

Alfred Neave Brayshaw was a remarkable man who devoted his life to his faith as a teacher, lecturer and writer. He was a pioneer of liberal Quakerism who had personal connections with both the Rowntree and Cadbury families, much respected and revered throughout the Quaker community both in Britain and abroad, and by generations of young men from Quaker schools across the country. It’s good that we can also count him a chess player and composer.

I’m particularly grateful to acknowledge this highly informative post by Quaker blogger Gil S of Skipton: many thanks.

Other sources and acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Archive

Wikipedia

Yet Another Chess Problem Database (Brayshaw here)

Yorkshire Chess History (Steve Mann) (Brayshaw here)

Solutions to problems (click on any move to play them through):

Problem 1.

You might consider this slightly unsatisfactory because there’s a short mate after 1… Kd6.

Problem 2.

Problem 3.

Problem 4.

I don’t quite see the point of this. White just creates a threat which Black has no sensible way of meeting.

Problem 5.

There’s a short mate here after 1… Ke6.

Problem 6.

Problem 7.

It’s rather unfortunate that, after 1… Kf4, there are two ways to mate in two more moves.