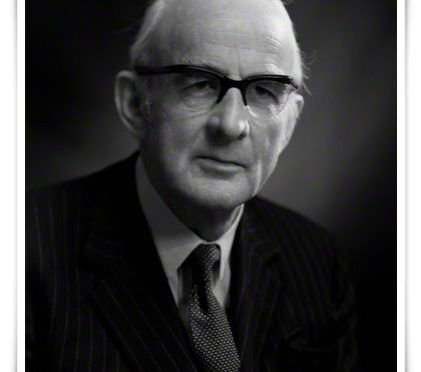

BCN remembers Sir Stuart Milner-Barry KCVO CB OBE who passed away on Saturday, March 25th, 1995 in Lewisham Hospital, London aged 88. He was laid to rest in the Great Shelford Cemetery, Cambridge Road, Great Shelford, Cambridge CB22 5JJ.

A memorial service was held for him at Westminster Abbey on 15 June 1995.

Philip Stuart Milner-Barry was born on Thursday, September 20th 1906 in Mill Hill in the London Borough of Barnet. Mill Hill falls under the Hendon Parliamentary constituency.

Parents

His parents were Lieutenant-Commander Edward Leopold (1867-1917) and Edith Mary Milner-Barry (born 17th May 1866, died 1949, née Besant). Edward was in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, H.M.S. “Wallington.” Prior to his war service his father was a professor of modern languages at the University of Bangor and Edith was the daughter of Dr. William Henry Besant, a renowned mathematical fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge University.

Stuart was the second born of six children, There was an older sister Alda Mary (18th August 1893-1938) and four brothers Edward William Besant (?-1911) , Walter Leopold (1904-1982), John O’Brien (4 December 1898 – 28 February 1954) and Patrick James . Many of the Milner-Barry family were laid to rest in the Great Shelford churchyard.

Stuart learned chess at the age of eight and his autobiographical article below goes into more depth.

He was educated at Cheltenham College, and won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he obtained firsts in classics and moral sciences.

On leaving Cambridge in 1927 he went to work at the London Stock Exchange (LSE).

According to the 1928 and 1929 electoral rolls he was living with his mother Edith and his brothers Walter and John O’Brien at 50 De Freville Avenue, Cambridge CB4 1HT:

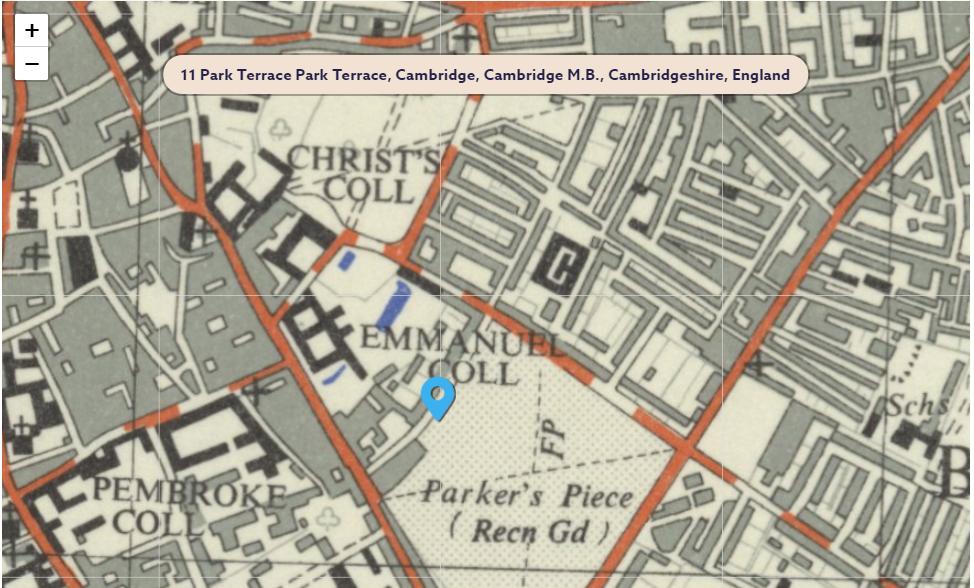

In 1931 the family had relocated to 11, Park Terrace, Cambridge which is nearby to Emmanuel College. Now living with the family was brother Patrick James.

He discovered that he did not enjoy his LSE work and switched careers to became chess correspondent of The Times in 1938.

At the time (September 29th) of the 1939 register he (aged 33) was living as a journalist in a household of three with his mother Edith who carried out “unpaid domestic duties” and sister Alda who was of “private means”.

Honours

In 1946 Stuart was awarded the OBE from the Civil Division in the New Years Honours . The citation reads that was “employed in a Department of the Foreign Office”. A modern translation of this was he was engaged in Top Secret work at Bletchley Park alongside Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman and Hugh Alexander and was thus honoured for his war work. More on this later…

After the war he worked in the Treasury, and later in 1966 administered the British honours system where he helped to facilitate the award of honours to other chess players ultimately retiring in 1977.

As well as the OBE he was made Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) in 1962 and Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCV0) in 1975.

A conference room was named after him at the Civil Service Club, 13 – 15 Great Scotland Yard, London SW1A 2HJ.

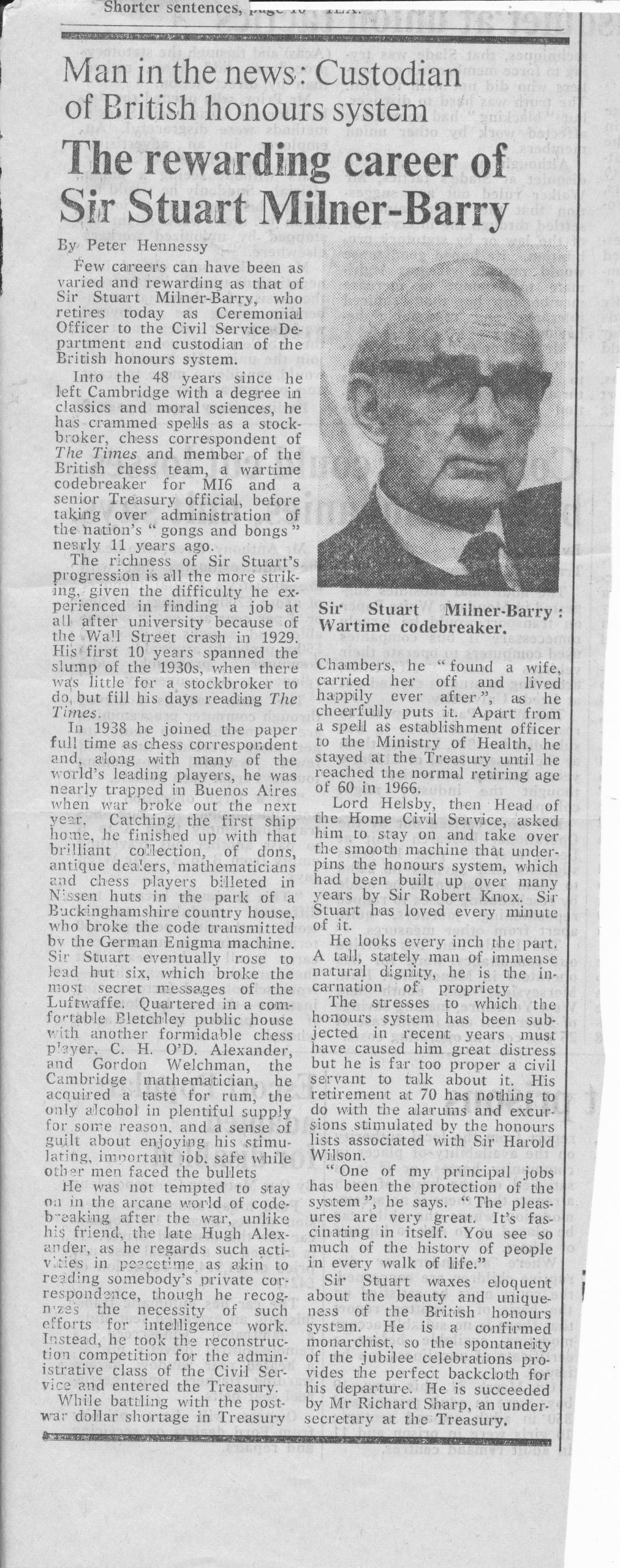

Peter Hennessy* and The Rewarding Career of Sir Stuart Milner-Barry

*Peter Hennessy is a renowned historian and journalist. The following was originally published in The Times in 1977 following PSMBs retirement.

“Few careers can have been as varied and rewarding as that of Sir Stuart Milner-Barry, who retires today as Ceremonial Officer to the Civil Service Department and custodian of the British honours system.

Into the 48 years since he left Cambridge with a degrees in classics and moral sciences, he has crammed spells as a stockbroker, chess correspondent of The Times and member of the British chess team, a wartime codebreaker for MI6 and a senior Treasury official before taking over administration of the nations “gongs and bongs ” nearly 11 years ago.

The richness of Sir Stuart’s progression is all the more striking given the difficulty he experienced in finding a job at all after university because of the Wall Street crash in 1929. His first 10 years spanned the slump of the 1930s, when there was little for a stockbroker to do, but fill his days reading The Times.

In 1938 he joined the paper full time as chess correspondent and, along with many of the world’s leading players, he was nearly trapped in Buenos Aires when war broke out the next year (ed. should be month rather than year). Catching the first ship home, he finished up with that brilliant collection of dons, antique dealers, mathematicians and chess players billeted in Nissen huts in the park of Buckinghamshire country house, who broke the code transmitted by the German Enigma machine.

Sir Stuart eventually rose to lead hut six, which broke the most secret messages of the Luftwaffe. Quartered in a comfortable Bletchley public house with another formidable chess player, C. H. O’D. Alexander, and Gordon Welchman, the Cambridge mathematician, he acquired a taste for rum, the only alcohol in plentiful supply for some reason, and a sense of guilt about enjoying, his stimulating, important job, safe while other men faced the bullets.

He was not tempted to stay on in the arcane world of code-breaking after the war, unlike his friend, the late Hugh Alexander, as he regards such activities in peacetime as akin to reading somebody’s private correspondence, though he recognizes the necessity of such efforts for intelligence work. Instead, he took the reconstruction competition for the administrative class of the Civil Service and entered the Treasury.

While battling with the post-war dollar shortage in Treasury Chambers he “found a wife, carried her off and lived happily ever after”, as he cheerfully puts it. Apart from a spell as establishment officer to the Ministry of Health, he stayed at the Treasury until he reached the normal retiring age of 60 in 1966.

Lord Helsby, then Head of the Home Civil Service, asked him to stay on and take over the smooth machine that underpins the honours system, which had been built up over many years by Sir Robert Knox. Sir Stuart has loved every minute of it.

He looks every inch the part, a tall stately man of immense natural dignity, he is the incarnation of propriety. The stresses to which the honours system has been subjected to in recent years must have caused him great distress but he is far too proper a civil servant to talk about it. His retirement at 70 has nothing to do with the alarums and excursions stimulated by the honours lists associated with Harold Wilson.

“One of my principal jobs has been the protection of the system”, he says. “The pleasures are very great. It’s fascinating in itself. You see so much of the history of people in every walk of like”.

Sir Stuart waxes eloquent about the beauty and uniqueness of the British honours system. He is a confirmed monarchist, so the spontaneity of the jubilee celebrations provides the perfect backcloth for his departure. He is succeeded by Mr. Richard Sharp, an under-secretary at the Treasury.”

Below is the original article:

Marriage to Thelma

In the third quarter of 1947 Stuart married Thelma Tennant Wells in Westminster. A consequence of the “rules of the day” of the marriage was that Thelma had to resign her post in the Treasury immediately. (Ed: this somewhat antiquated view of life was finally corrected in 1972 when the Civil Service dispensed with this rule).

Lady Thelma was to support Stuart in his chess activities for their married life. She also served as the first UK Director of Women’s Chess and made many lasting friendships in the chess world. She was buried together with Stuart in 2007. Stuart himself was President of the British Chess Federation between 1970 and 1973 as well as being Director of International Chess following his presidency.

Stuart and Thelma had three children, one son and two daughters: Philip O. (born 1953), Jane E (born 1950) and Alda M (born 1958).

Stuart was knighted on January 1st 1975 for his role as the “Ceremonial Officer of Civil Service Department” between 1966-77. Technically the knighthood is known as a KCVO.

Milner-Barry was Southern Counties (SCCU) champion for the 1960-61 season.

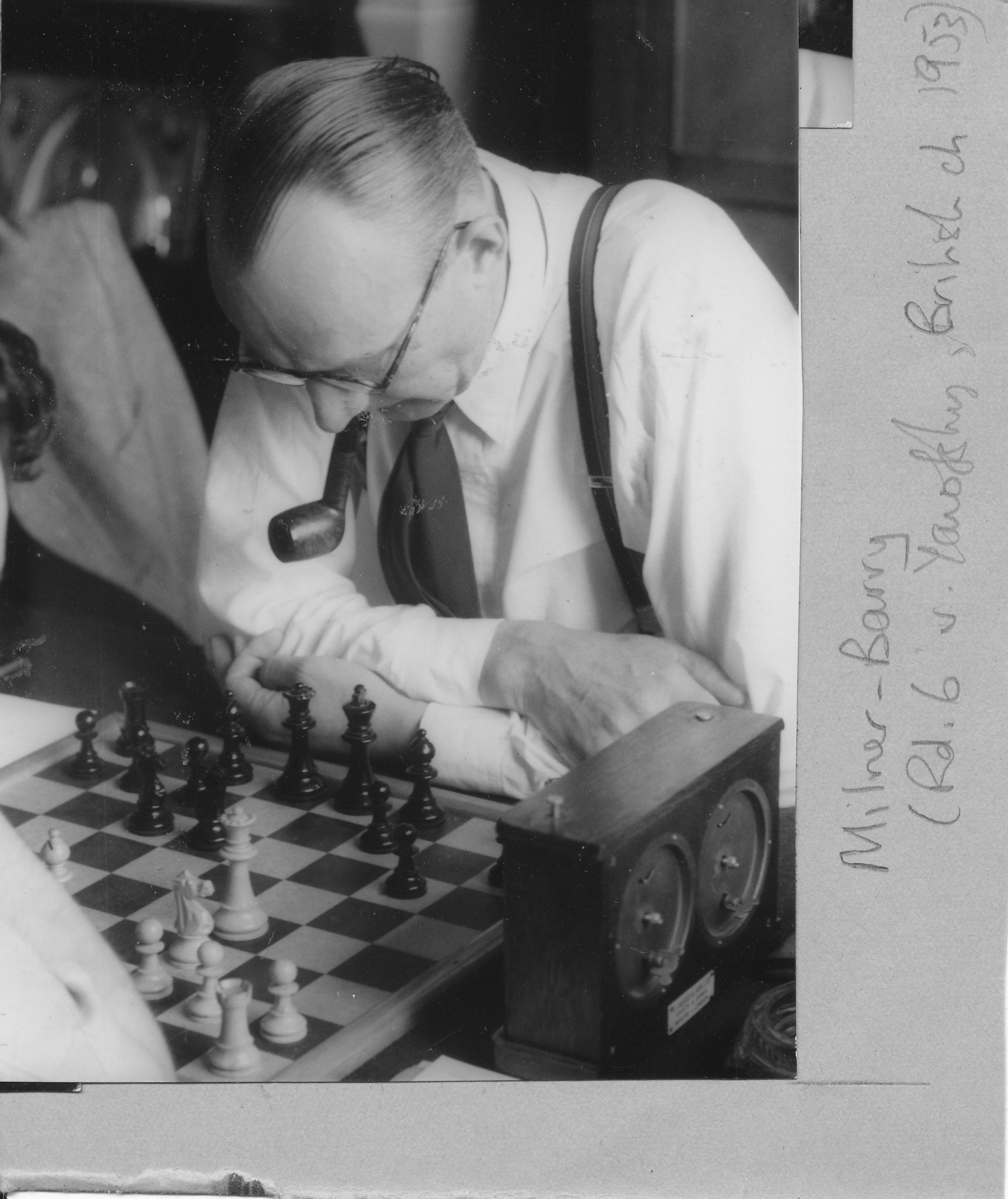

He first competed in the British Championship in 1931 and made regular appearences as late as 1978: a span of 47 years!

In their retirement years Stuart and Thelma lived at the salubrious location of 43 Blackheath Park, Blackheath, London SE3 9RW.

Autobiography

In June of 1933 at the age of 27 Stuart wrote an autobiographical piece for British Chess Magazine to be found in Volume LIII (53, 1933), Number 6 (June), pp. 241-2 as follows:

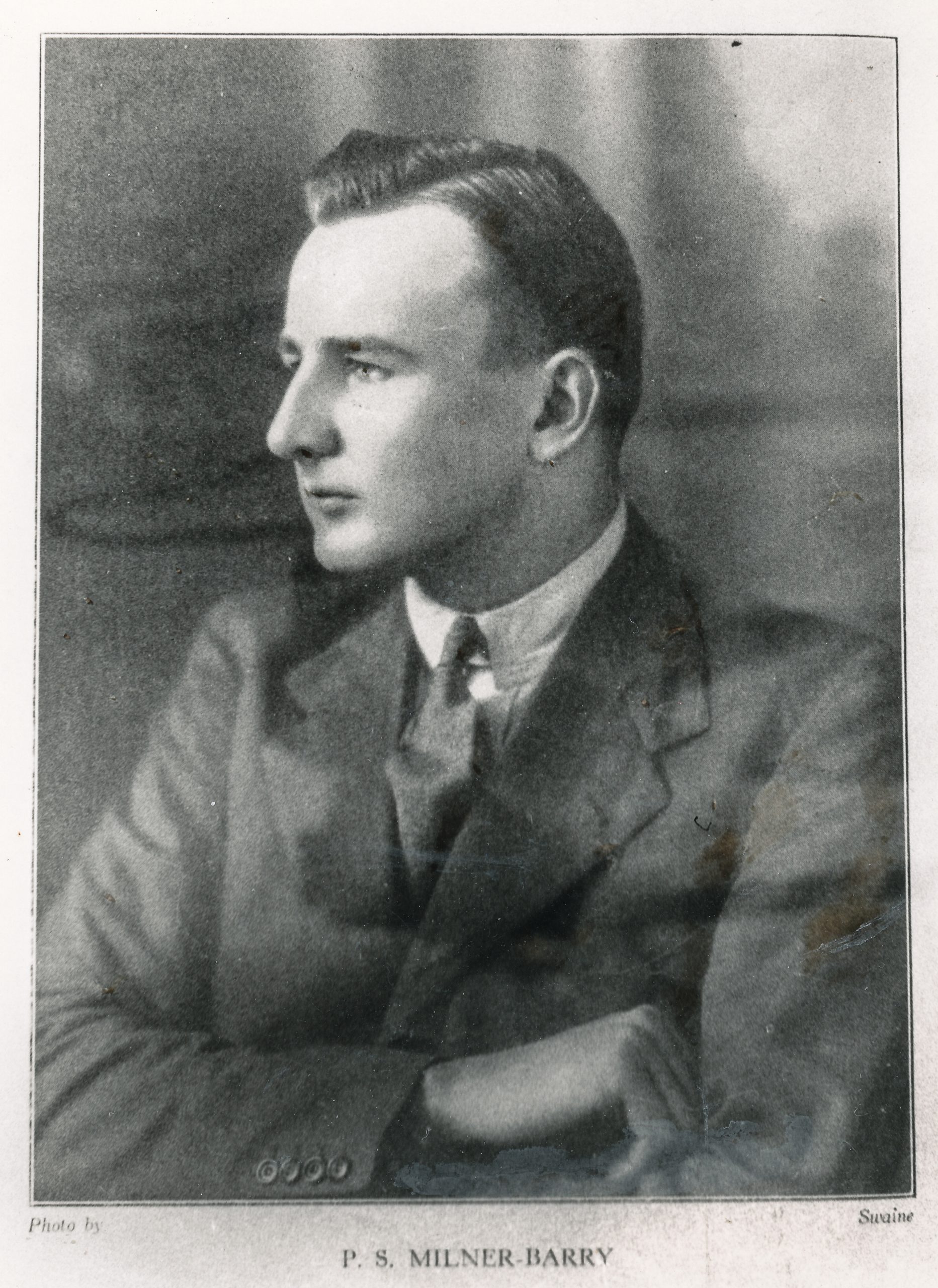

P.S. Milner-Barry

Champion of the City of London Chess Club

I learned chess at the age of eight and played regularly after that with members of my family. My first-class practise (with due respect to my family) began at fourteen, when Mr. Bertram Goulding Brown and started a series of serious friendly games which has continued ever since, almost without interruption. The vast majority of these games were begun with 1 P-K4, P-K4, and as we both eschewed the Lopez and the Four Knights, we have acquired a fairly extensive knowledge of the older forms of the King’s side openings – King’s Gambit (all sorts), Vienna, Guioco Piano, Evans’s Gambit, Danish Gambit, Bishop’s Opening, etc. These games have undoubtedly born the most important influence in my development, apart from which the serious friendly game is to me much the most enjoyable form of chess. We each have runs of success, and there has never been much to choose between us.

(An aside : Stuart wrote a extensive obituary of Bertram Goulding Brown which appeared in British Chess Magazine, Volume LXXXV (85, 1965), Number 12(December) pp.344-45 in which he noted:

B. Goulding Brown was my oldest and closest Cambridge friend, I started playing with him in 1920, and we have played ever since, though, alas, not nearly so often since the War as in the 1920s and 1930. Our last games, when he was eighty three, were played about a year ago in the same book-congested upstairs study at Brookside as all the others had been. Both were cut-and-thrust draws: a Kieseritzky Gambit from myself and Two Knights’ (with 4.P-Q4 for White) were typical of the openings we adopted. We were planning another this Autumn, but he died suddenly and peacefully at the end of August, )

I have also been very fortunate in playing a good deal with C.H.O’D. Alexander. Our games have taken the form of a series of short matches (first player to win three games) played with clocks. Alexander was already stronger than me when he came up to Cambridge, and he won the University Championship from me in his first year and my fourth.

All three matches have been won by him, the first easily and the last two by the narrowest possible margin; a fourth now in progress looks like coming to an early and ignominious conclusion (Score 0-2-2). These results have neither surprised nor disappointed me : I would not back any player in England to do better.

(ed. For more detail on PSMBs matches with Hugh we refer to you our article on Hugh).

In 1923 I won the first Boy’s Championship at Hastings, but lost badly the following year (ed. Alexander won).

Since then I have competed twice at Hastings, once tieing with Miss Menchik in the Major Reserve for the first place and once for the last, in the Major. In between I played in the Major Open at Tenby, and came out fifth, with my first important win against Znosko-Borovsky.

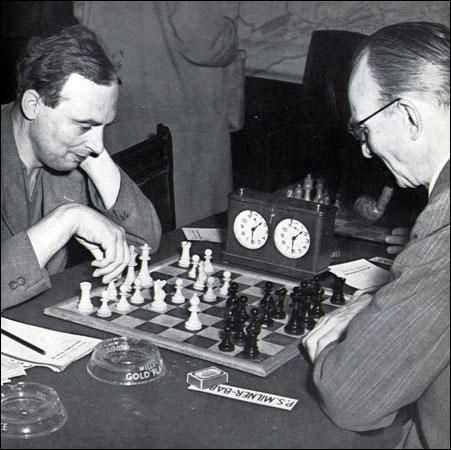

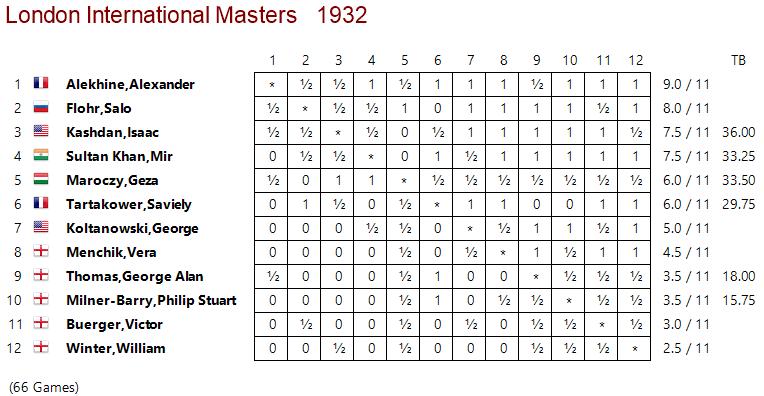

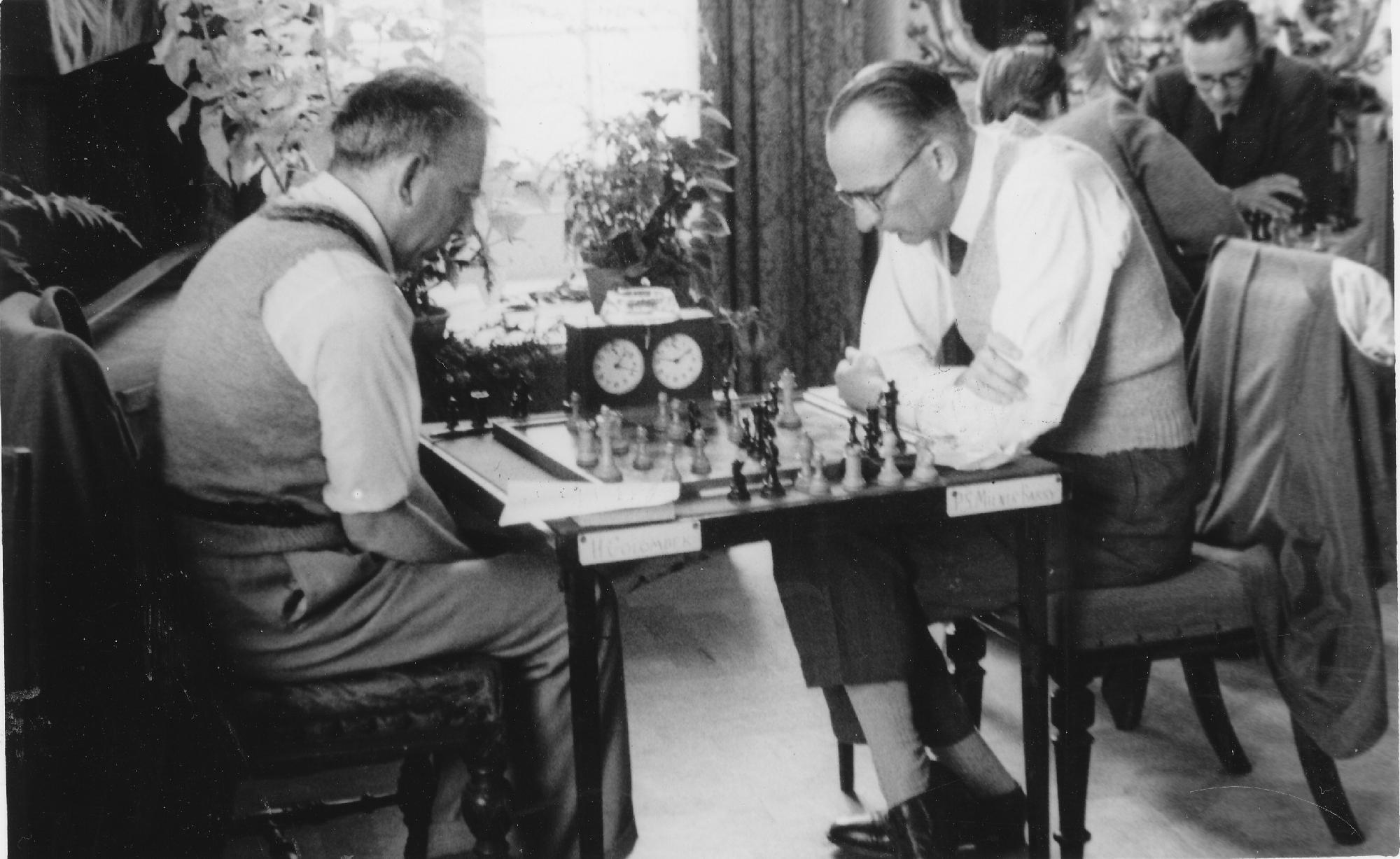

Meanwhile I played four years against Oxford, with somewhat chequered results. The first year I won against G. Abrahams, the second and third years, I played K.H. Bancroft and scored a (very fortunate) draw and a win, while finally I permitted Abrahams to fork my King and Queen with a Knight, a performance unhappily repeated by R.L. Mitchell in the following year (his Queen was pinned by a Bishop). Since then the spell has been broken. In 1931 I played in the British Championships at Worcester, and was quite satisfied with my form, though my score of 5 out of 11 was nothing to write home about. In February 1932, I have the great good fortune to fill a vacant place in the Sunday Referee* London International Tournament, an extremely exhausting but very valuable experience which I greatly appreciated.

*The Sunday Referee was a newspaper of the time which was adsorbed into The Sunday Chronicle in 1939.

My score of 3.5 out of 11, equal with Sir George Thomas and above W. Winter and V. Buerger, was quite as good as I expected. After this came the Cambridge Tournament, which, though a very delightful little congress, was a fiasco from my point of view. Three of my opponents were unkind enough to show their best form against me, and two other games I spoilt by clock trouble.

I do not expect to play much serious competitive chess in future. I admire sincerely the business man who is ready, after a hard day at the office, to undergo a further four hours of strenuous mental exertion; and who is also prepared to spend his all too brief holidays in the same exhausting pursuit. Moreover, while many players find the atmosphere of match and tournament play a stimulus or an inspiration, it only renders me nervous, and though this does not affect my play it certainly interferes with my enjoyment. As long as I can play my week-end games with B.G.B., and inveigle Alexander from Winchester to add another to his monotonous series of victories, I shall not much mind if I can only occasionally take part in congresses. ”

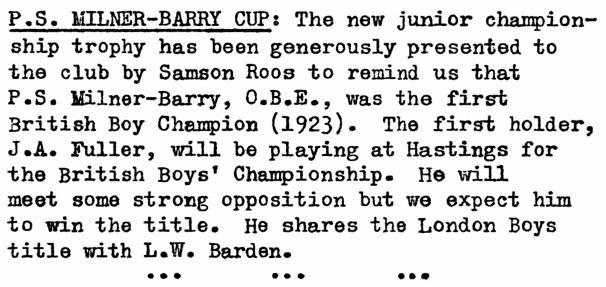

PS Milner-Barry Cup

In issue #53 (April 1946) of West London Chess Club’s Gazette we have a news item concerning a newly inaugurated trophy called the PS Milner-Barry Cup:

Sergeant on Milner-Barry

Writing in A Century of British Chess (Hutchinson, 1934), PW Sergeant records in Chapter XXI, 1925 to 1934:

The City of London C.C.’s Championship Tournament which ended this (1933) spring deserves special mention; for it introduced an entirely new name on the list of champions, that of P.S. Milner-Barry, formerly of Cheltenham College and of Cambridge University. Ten years previously he had won the first boys’ championship at Hastings.

Now, he won the City of London Championship with a score of 11 out of 14, followed by the bearers of such noted names as R.P. Michell (10 points), Sir George Thomas (9), and E.G. Sergeant (8.5). It caused some surprise, therefore, when it was found that he was not selected as a British representative at Folkestone.

Golombek on Milner-Barry

Surprisingly and disappointingly there is no direct entry in either Hooper & Whyld or Sunnucks for Sir Stuart but (as you might expect) Harry Golombek OBE does not let us down in The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977):

“British master whose chess career was limited by his amateur status but whose abilities as a player and original theorist rendered him worthy of the title of international master.

Born at Mill Hill in London, he showed early promise and in 1923 won the British Boys Championship, then held at Hastings.

He studied classics at Cambridge and developed into the strongest player there. At the university he was to meet (ed. three years later) C. H. O’D. Alexander with whom he played much chess.

Though nearly three years younger, Alexander exerted a strong influence over him and both players cherished and revelled in the brilliance of play in open positions.

By then along with Alexander and Golombek, he had become recognized as one of the three strongest young players in the country. Whilst not as successful as they were in tournaments as the British championship in which stamina was essential, he was a most formidable club and team match player, as he had already shown in 1933 when he won the championship of the City of London Club ahead of R. P. Mitchell and Sir George Thomas.

He played in his first International Team tournament at Stockholm 1937 and was to play in three more such events : in 1939 at Buenos Aires where, on third board, he made the fine score of 4/5 ; in Helsinki 1952; and in Moscow 1956 where, again on third board, he was largely responsible for the team’s fine showing.

In 1940 he shared first prize with Dr. List in the strong tournament of semi-international character in London and then, like Alexander and (later) Golombek, helped in the Foreign Office code-breaking activities at Bletchley Park for the duration of the Second World War. Staying in the Civil Service afterwards, he rose to the rank of Under-Secretary in the Treasury and was knighted for his services in 1975.

Below is footage (start at 1′ 55″) of Sir Stuart discussing the talent of Malik Mir Sultan Khan:

After the war, too, he had some fine results in the British championship, his best being second place at Hastings in 1953.

Hartston on Milner-Barry

The following article is sourced from November 1995 edition* of Dragon, the Cambridge University Chess Club magazine:

(*Edited by Jonathan Parker)

“I first met Sir Stuart Milner-Barry when I was fifteen years old (1962) playing in a tournament in Bognor Regis who played some rustic king’s pawn opening against me, sacrificing a pawn for nothing in particular and then astonished by writing “castles” in full on his scoresheet. I think he used “kt” for a knight too. I thought I had discovered a true relic from a bygone age and the more I got to know him I realised the more correct that judgement was.

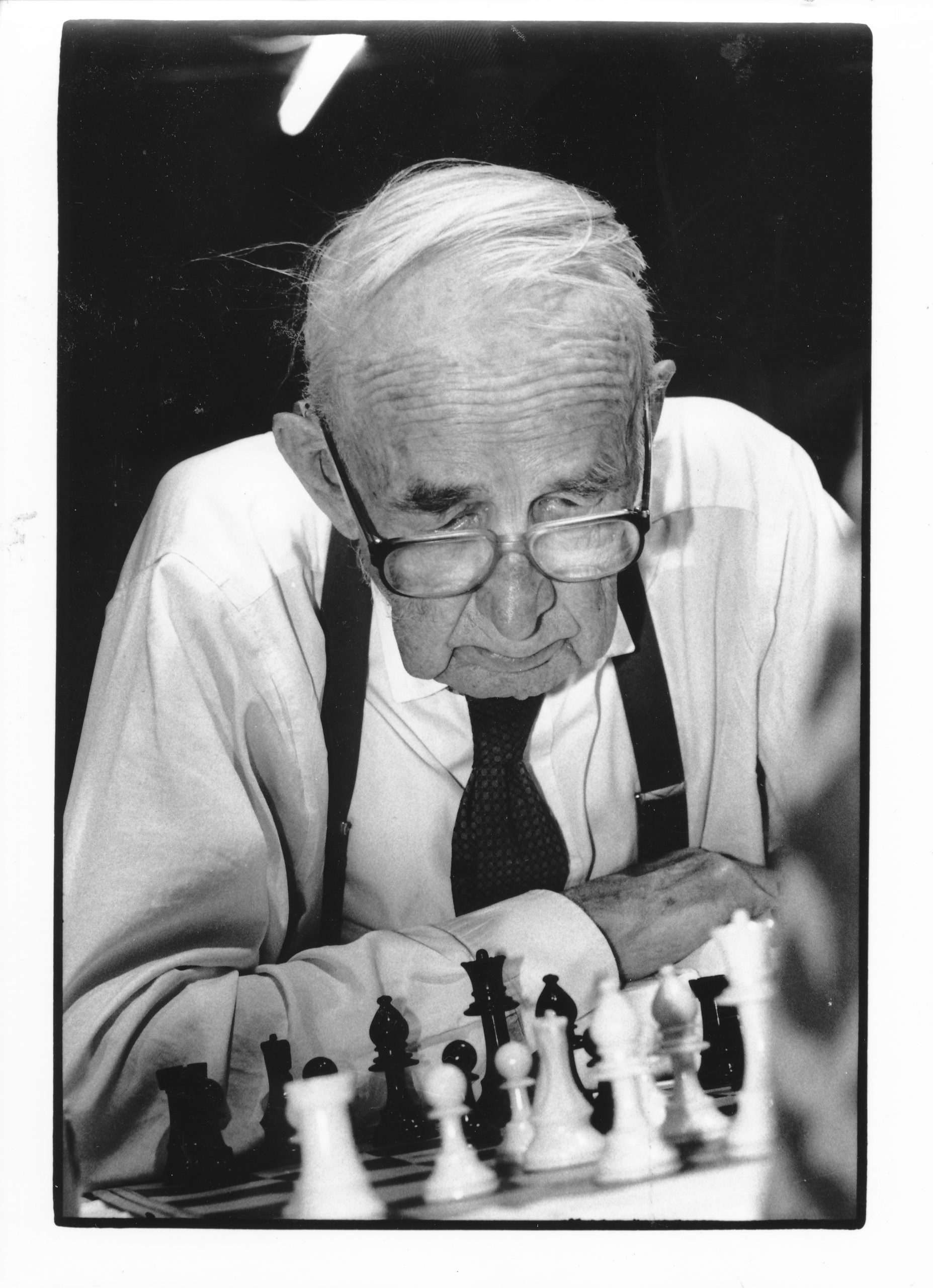

Milner-Barry was the last of the true gentlemen amateurs and was one of the few people I have ever met who played chess for the sheer love of the game.

A few typical incidents may give a flavour of his unique personality. First and most typical was the way he would resign: with a firm handshake, a smile and a booming whisper of ‘You are far too good for me I’m afraid!’ When I first heard those words I was totally taken aback : What was this, a chessplayer acknowledging that his opponent was better than him? Impossible!

Once, at close of play in a county match against Milner-Barry I had the extra pawn in a difficult queen and pawn ending. We analysed a little with most variations suggesting I was winning. It was the kind of position you would send for adjudication even if you are convinced it is lost. It avoids having to resign anyway and the adjudicator may always discount the pawns. But, Sir Stuart never thought like that. After ten minutes analysing he extended his hand and congratulated me.

Finally there was the splendid incident in Moscow during the (Ed. 6th) European Team Championships in the late 1970s (Ed. 1977) Stuart was then the President of the BCF and took up an invitation of his old friend the British Ambassador to the USSR (Ed. Sir Howard Smith) to visit the event. Since he was staying at the Embassy he had a KGB tail assigned to him to follow him everywhere. On one of his morning walks Sir Stuart got lost and was not certain which bridge he should be on to get back to the Embassy. So, he turned around and walked back to the not very secret policeman, followed him and asked for directions! For the rest of his stay they walked practically hand-in-hand.

Whilst most of us knew Stuart as an amiable old gent who played for Kent and in the Lloyds Bank Masters who could still play brilliant attacking games in his eighties most knew little of his distinguished career in real life.

We suspected with some justification that in his civil service career he was responsible for doling out all those OBEs to chess players in the 70s and 80s when he was in charge of the honours list.

It was the wartime work at Bletchley Park that was Milner-Barry’s greatest achievement. As everybody knows the allies won the Second World War mainly because of the brilliant code-breaking work of the Cambridge quartet of Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman, Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry. Turing and Welchman were mathematical geniuses, Milner-Barry was the supreme administrator and Alexander straddled the gap with great talents in both areas. The group of four were known as “The Wicked Uncles”

The astonishing achievement at Bletchley was not so much in breaking enemy codes as maintaining complete secrecy of the entire operation for the duration of the war. Only with such people as Milner-Barry and Alexander in charge could such a large operation be run so successfully without anybody knowing about it.

Milner-Barry’s importance in the running at Bletchley may be judged from the fact that he personally delivered the note to Winston Churchill stressing overriding importance of their work asking for more funds.

Compared with that the invention of the Milner-Barry Gambit and the Milner-Barry variation of the Nimzo-Indian are minor achievements.

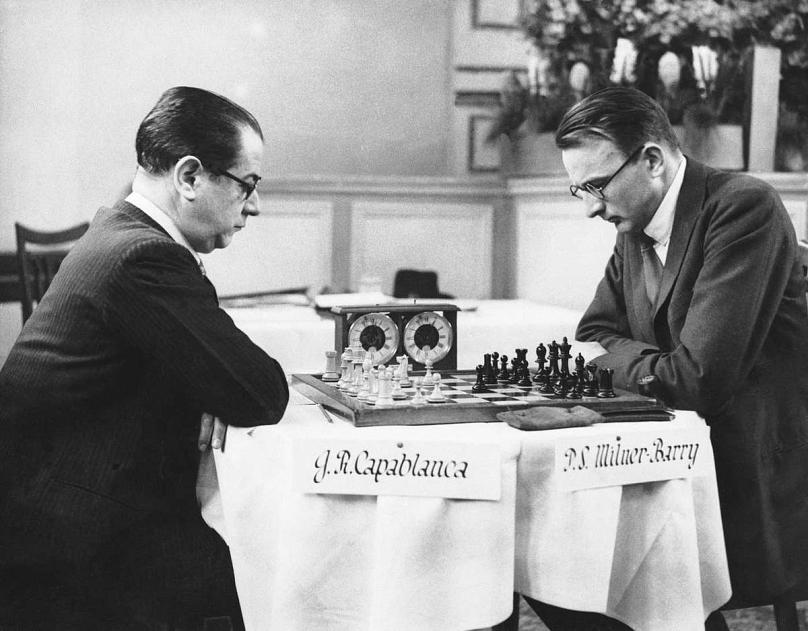

Sir Stuart was proof that nice guys can be chess players although one cannot help suspecting he would achieved even better results if he had even a slight streak of nastiness about him. He would surely have not let Capablanca off the hook in Margate in 1938 when the attacking player secured a winning position against the ex-champions dragon variation and he would have surely also not let the British Championship slip from his grasp in 1953 when he finished as runner-up after losing his last two games.

He always performed well when playing in Olympiads (or Team Tournaments as they were known then) for England during the 1930s and 50s. He was, after all, one of the most naturally gifted players this county has produced. What other Englishman has two opening (or even just one) named after him?

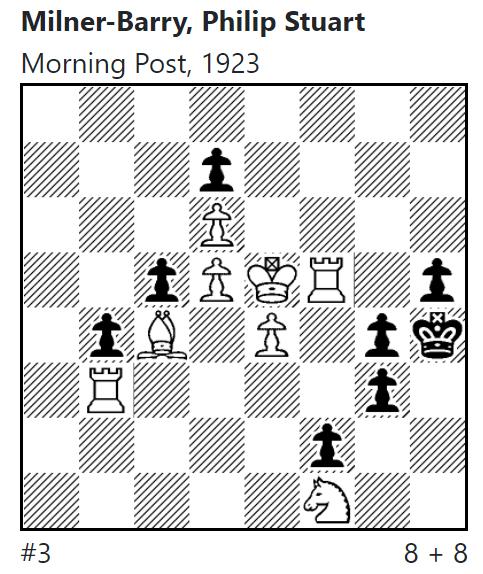

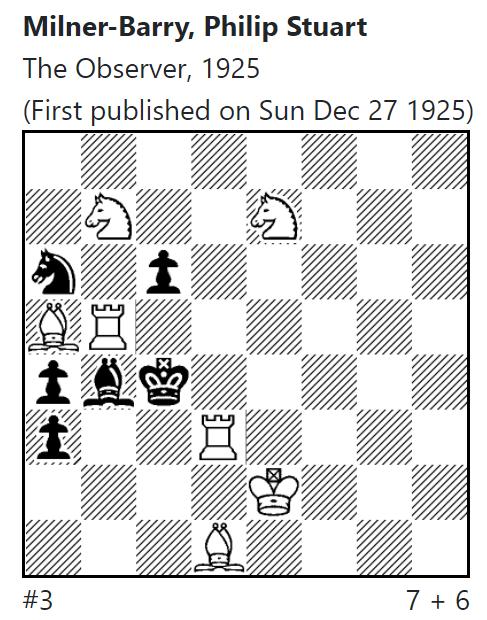

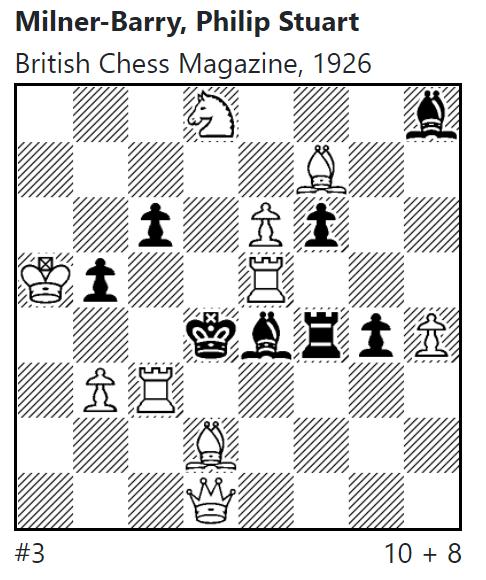

While at Cambridge while he won the University Championship in 1928, losing to Alexander in the following year, Milner-Barry composed some fine problems, a frivolity he never returned to later in his life.

An excellent though infrequent writer on the game, he wrote a fine memoir of C.H.O’D. Alexander in Golombek’s and Hartston’s The Best Games of C.H.O’D. Alexander, Oxford, 1976.”

An Obituary from Bernard Cafferty

From British Chess Magazine, Volume CXV (115, 1995), Number 5 (May), pp. 258-59 we have this obituary by Bernard Cafferty:

“Sir Philip Stuart Milner-Barry KCVO CB OBE (20 ix 1906 – 25 iii 1995) was the oldest of the British chess masters who came to prominence in the 1930s, He was always thought of in conjunction with his great friends Hugh Alexander and Harry Golombek who both predeceased him. The length of Stuart’s career is amazing – he was inaugural British Boy Champion in 1923 and was still playing for Kent first team in the Counties Championship of recent years, thus spanning a period of seven decades! Botvinnik spoke of him to me on my 1994 visit to Moscow.

Yet Stuart, who never gained the IM title, was always the true amateur and genuine English gentleman, whose sense of duty and tradition was very great. It speaks volumes of him that he agonised over whether he should attend the Times Kasparov-Short match of 1993, in a private capacity. He would have liked to watch the play, but as a former British Chess Federation President, 1970-73, he felt it was his duty not to lend any extra recognition to the contest other than that assigned it by the BCF.

Before the war, after graduating from Cambridge in Classics, he took some fine scalps including those of Tartakower and Mieses and should have beaten Capablanca at Margate 1939.

He worked, rather unhappily, in a stockbroking firm up to 1938 and it is in that capacity that his name appears on the official document that set-up the British Chess Magazine as a limited company in 1937.

During the war he played his part in the Bletchley Park code-breaking undertaking along with Alexander and Golombek, and after the war went into the Civil Service where he had a distinguished career at the Treasury. Then his career was extended as he spent his final working years in the patronage department that sifted recommendations for the honours list.

I recall asking him in 1981 if there was any chance that Brian Reilly could qualify for an award. Stuart’s diplomatic answer was to the effect that he was now retired but would drop a word in the right quarter.

Stuart represented England at the Olympiads or 1936, 1939, 1952 and 1956. At the last of these he played particularly well on fourth board. He was conscious that his old friend Hugh Alexander could not take part in Moscow because of the sensitive nature of his work in the Intelligence Service.

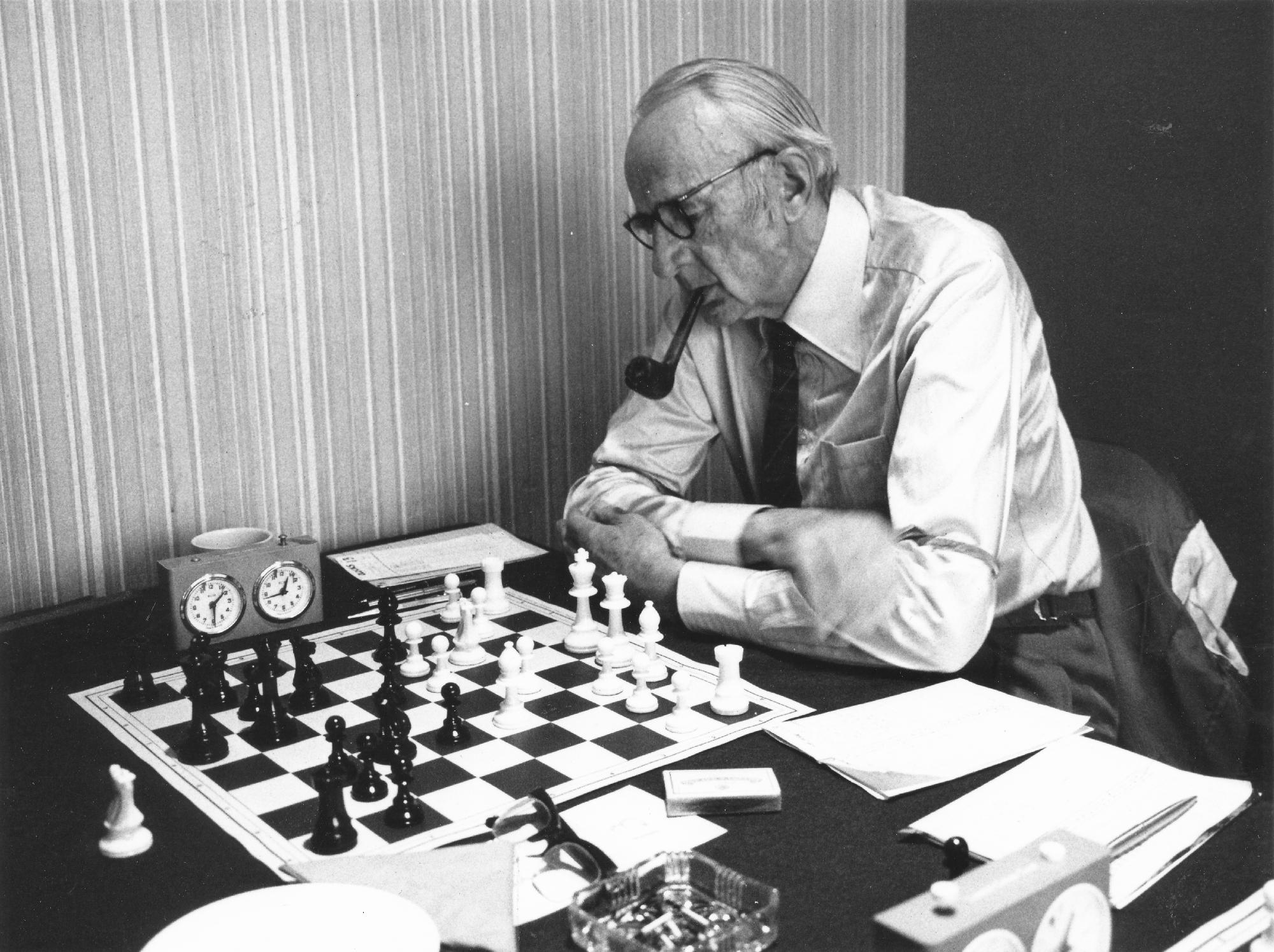

In playing style Milner-Barry, a tall gaunt figure, delighted in an open tactical fight.

He was The Times correspondent 1938-45, resigning the post to let Harry Golombek take over. His best result after the war, apart from the 1956 Moscow Olympiad, was probably his second place in the British Championships of 1953 at Hastings. The abiding impression of his opponents over the years must have been that here was a player who greatly enjoyed the game, win, lose or draw.

Certainly, that was my idea of him in the tussles we had from the British Championship of 1957 up to county matches in the 1980s.

We shall not see his like again. The England that formed his character is no longer with us.”

Kenworthy on Milner-Barry

Sir Stuart as a student was taught by his lecturer friend Gordon Welchman, later 1940 his Head of Hut. They were firm friends, a band of brothers, as per the rest of the chess players and mathematicians from the Interwar years at Cambridge University.

His studies were obviously well aligned to be a stockbroker in the City, plus the tedious details of Blotters and Order Management registration.

Obvious exceptions to this University circle was Dr Jacob Bronowski who was given the suspected 5th columnist treatment by authorities in Hull. Obviously, he would have been excellent.

Exception also according to John Hevriel was if you were also from Sidney Sussex, like Staff Sgt. then an RSM Asa Briggs, who was more Contract Bridge with this all friends crossword addicts team. Asa Briggs felt that Sir Stuart was initially badly rewarded leaving Hut 6 in 1945 for HM Treasury.

Sir Stuart was a noted top cribster, his crosswords, German and thinking from how the Nazi operator would think from his side of the board, obviously helped with Bombe cribs. He always played down his role and abilities in a diplomatic way. He was the facilitator and mentor to many, especially back to Gordon Welchman in his troubled times from 1974 onwards. Sir Stuart was not happy about the proposed book of the Hut 6 Story.

He was the bureaucrat who cared for the welfare of his staff, especially on tedious protract tasks which was the norm. He was into ethics, Quadrivium, logic and rhetoric, philosophy and his knowledge of German poets and Great German thinkers would have been invaluable in solving the Enigma puzzle and how might his opposite number blunder and be sloppy in procedures.

Milner-Barry Variations

Though never at home in close(d) positions, he was an outstanding strategist in the open game and it is significant that his most important contribution to opening theory was the Milner-Barry variation of the Nimzo-Indian Defence which is essentially as attempt to convert a close position into an open one (1.P-Q4, N-KB3; 2.P-QB4, P-K3; 3. N-QB3, B-N5; 4.Q-B2, N-B3).

Hooper & Whyld (1996) note:

“Sometimes called the Zurich or Swiss variation, this is a line in the Nimzo-Indian Defence introduced by Milner-Barry in the Premier Reserves tournament, Hastings 1928-9. This line became more widely known when it was played at Zurich 1934.”

Two famous opening lines are named after him – 4…Nc6 in the Nimzo-Indian (as above), and the gambit in the French Defence: 1.e4 e6;2.d4 d5;3.e5 c5;4.c3 Nc6;5.Nf3 Qb6;6.Bd3 cxd4;7.cxd4 Bd7;8.0-0 Nxd4;

Stuart played this line both in correspondence and over-the-board play. If Black takes the pawn with 10…Qxe5, White gets a fierce attack by 11,Re1 Qd6 (else 12.Nxd5) 12.Nb5.

There is also a sub-variation of the Caro-Kann which is named after Sir Stuart viz:

which is a Blackmar-Diemer style pawn sacrifice.

There is also a Milner-Barry variation in the Falkbeer Counter Gambit to the King’s Gambit thus:

which is an ancient line that he revived at Margate 1937.

and finally, there is a Milner-Barry Variation in the Petroff Defence:

giving a total of five named variations. How many English players have that many?

Problems and Compositions

Stuart developed an interest in problem composition in the 1920s

Further examples may be found on the excellent Meson Database maintained by Brian Stephenson

Milner-Barry on The English Chess Explosion

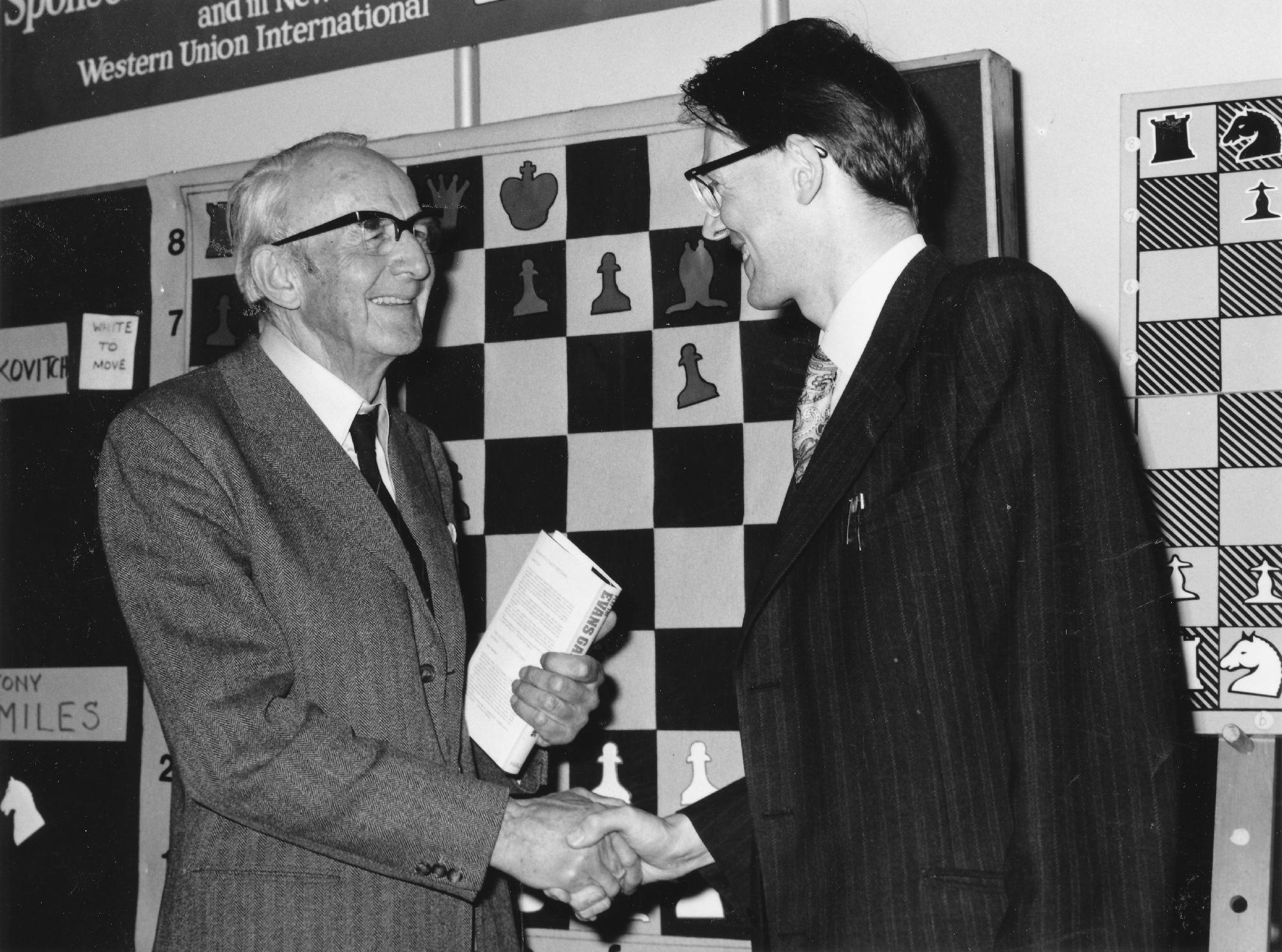

Stuart was a great supporter of the development of British chess. Nothing would have given him more pleasure than to witness the meteoric advances of English players in the 1970s. Indeed, he wrote the foreword to the English Chess Explosion (Batsford, 1980) by Murray Chandler and Ray Keene:

“It gives me great pleasure to have been asked to write a foreword for this book. Nothing has given me more satisfaction than the flowering of British chess talent that has taken place in the past few years.

Between the wars, though we had some splendid players like H. E. Atkins, Sir George Thomas and F. D. Yates, we were a second rate power at chess: in the great Nottingham tournament of 1936, for example, our quartet brought up the rear, and that was where, with occasional shining exceptions, our representatives in international tournaments tended to find themselves. Similarly, after the war in the 1950’s and 1960’s, in spite of Alexander and Penrose, we seldom achieved a really creditable place in the Olympiads.

Alexander who retired early from the arena because of the exacting demands of his profession, must have had rather a depressing time as non-playing captain.

I myself date the renaissance from the Spring of 1974 when we won a closely contested match against West Germany at Elvetham Hall.

Thereafter we went from strength to strength, with the appearance year by year of highly talented, original and adventurous young men from the Universities – Keene and Hartston, closely followed by Miles, Stean, Nunn, Mestel, Speelman, and a still younger generation of schoolboy prodigies like Nigel Short.

The peak of our performance so far has been the third place (after the USSR and Hungary) last winter in the finals of the European Team Tournament at Skara (compared with our eighth and last place at Moscow in 1977).

How did all this come about in the short space of six years? The Spassky-Fischer match of 1972 was a watershed. Since then, and the first time, it has been possible for able young men from universities to consider chess seriously as a full-time profession, or at least as a career to which they devote the major part of their time and interest, Secondly, the fruits were being reaped of the unobtrusive but devoted spadework in junior training pioneered by Barden, Wade and many others. Lastly, no doubt, sheer good fortune smiled upon us in the simultaneous emergence of a group of brilliant enthusiastic and likeable young men, five of them already grandmasters and others likely to become so before long.

It is sad that Alexander, who did so much to uphold the prestige of British chess in the doldrums, did not survive to witness the transformation. I would like to wish the BCF President, David Anderton, and Alexander’s successor as captain, all possible success for the future.”

In the March issue of CHESS for 1963, (Volume 28, Number 427, pp.147-155) William Winter wrote this:

P. S. Milner-Barry is a close friend of Alexander’s and plays like him, though not quite so well. So far the Championship has always eluded him, though he seemed to have it within his grasp at Buxton where he played superb chess for nine rounds and cracked in the last two. I fancy that the physical strain of these long Swiss tournaments

is rather too much for him. Like Alexander he has a most attractive style and one or two of his combinative games will certainly live after him.

More from Bletchley Park

(The original may be found here)

A brief biography, formerly displayed in the ‘Hall of Fame’ in Bletchley Park mansion. Stuart Milner-Barry had achieved fame as a champion chess player when he came to Bletchley Park early in 1940. He led the ‘cribsters’ team in Hut 6 from its opening in January 1940, becoming head of the Hut in March 1944. The work of Milner-Barry and his team lay at the heart of the triumph over the German Luftwaffe & Army Enigma codes. After the war he had an outstanding career in the civil service. Philip Stuart Milner-Barry was born on 20 September 1906 in London; He went to Cheltenham College and on to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he achieved a first in both the classical and moral sciences triposes. He became a not-notably enthusiastic stock broker, though it was chess that filled his life. He had been boy chess champion of England in 1923, playing for England before and after the war. He was chess

correspondent of the Times from 1938 and throughout the war. It was Gordon Welchman, a friend from their days at Trinity together, who persuading Milner-Barry to join Bletchley Park.

He arrived in January 1940 joining the newly created Hut 6, and was encouraged by Welchman to study the decrypts that were beginning to emerge from the Zygalski sheets being operated by John Jeffreys. Welchman wanted Milner-Barry to develop an intimate knowledge of the German cipher clerks and radio operators. When the Germans dropped the use of the repeated indicator, as they did on 1 May 1940, Hut 6 would have to rely on its knowledge of the traffic to find suitable cribs to enable the Bombes to operate, and in the meanwhile to make use of the careless procedural habits of some of the German operators.

Milner-Barry had noted that the cipher clerks tended to use addresses and signatures that were both long and stereotyped, providing a fruitful source for cribs. A crib had to be a phrase of about 13 characters long that was very likely to be found in certain easily identified messages, but also had to have linguistic features that provided good ‘closed loops’ for the bombe menus. The use of ‘kisses’, cribs derived from suitable decrypted messages from other keys, often provided the first break into a new key. Milner-Barry organised a team of wizards, as Welchman called his cribsters, who eventually were able to provide good keys for Hut 6 to be able to break into most of the Luftwaffe keys and then some of the Army keys. Milner-Barry became recognised as Gordon Welchman’s deputy, and when Welchman left in March 1943, to become responsible for mechanisation projects, it was Milner-Barry who became Head of Hut 6. Milner-Barry signed the Turing letter in October 1941 and it was he who took the letter directly to Downing Street. It drew Churchill’s attention the extreme shortage of support personnel in the Enigma huts. His powers of smooth administration now became clear as Hut 6 grew, reaching over 550 in total, one of the largest teams in Bletchley Park.

Milner-Barry was a quiet, undemonstrative, highly effective leader who believed in delegation and was always to be seen sporting a very large pipe. His reports show that he was totally unflappable, in the midst of the problems for Hut 6 created by the tightening of German cipher security in 1944, which they largely overcame. Stuart Milner-Barry was recruited to Whitehall in June 1945. He rose rapidly, becoming the ceremonial officer in the Civil Service Department. He received an OBE in 1946, a CB in 1962, and a knighthood in 1975. He married Thelma Wells in 1947 and they had three children. He died in Lewisham on 25 March 1995. He had repeated his visit to Downing Street in October 1991, with a letter signed by 10,000, asking for Bletchley Park to be preserved as a monument to the great war-time work.

Further Material

An obituary from The Independent by Bill Hartston

An article from Spartacus Educational

Here are his games from chess.com

More on his time at Bletchley Park

The papers of Sir Stuart Milner-Barry

Here is his Wikipedia entry

According to Edward Winter in Chess Notes PSMB lived at these addresses :

- 11 Park Terrace, Cambridge, England (Ranneforths Schachkalender, 1938, page 78).

- 43 Blackheath Park, Blackheath, London SE3 9RW, England (letter reproduced in C.N. 3809).

Edith Milner-Barry’s maiden name sounded vaguely familiar in another connection, so I did a bit of looking-up. Found that her uncle Frank Besant was the husband of Annie Besant (1847-1933), political activist and a prominent member of the Theosophical Society. Not a blood-relation, but an interesting link all the same.