I’ve just returned (on the eve of publication of this article) from a concert in which the distinguished baritone Roderick Williams performed a song composed by Sally Beamish. A few weeks ago I was at a gig where one of the musicians talked about drinking Beamish at the Cork Jazz Festival.

If you’re in Dublin you drink Guinness: if you’re in Cork you drink Beamish. Whether Sally drinks Beamish I don’t know, but she comes from the same family.

William Beamish and William Crawford founded the Cork Porter Brewery in 1791, beginning brewing the following year. William Beamish came from a distinguished family of English settlers.

Several of their family were competitive chess players in the first half of the last century. The unfortunately initialled FU Beamish was active in the Bristol area in the years leading up to the First World War, and A (or sometimes AE) Beamish was playing in London at the same time. Then there was Captain EA Beamish, who was a tournament regular for a decade or so either side of 1940.

There is some confusion about AB/AEB and EAB which I hope this article will resolve.

One of William’s many children was a son named Charles, born in 1801 (Sally is descended from his brother Richard): it’s his branch of the family who were chess players. Charles and his first wife, Louisa Howard, had four children: Ferdinand, Albert, Victoria and Alfred. He had another four children by his second wife, but, apart from noting that one of his daughters was named, with a distinct lack of political correctness, Darkey Delacour Beamish, they needn’t concern us.

Ferdinand was born in France in 1838, married Frances Anne Strickland at St John the Evangelist, Ladbroke Grove, London in 1876, then moved back to Cork where their children were born: Ferdinand Uniacke (1877), Walter Strickland, Francis Bernard, Gerald Cholmley and finally their only daughter, Agnes Olive.

It was Ferdinand Uniacke Beamish, unfortunately initialled, yes, but also splendidly named, who was our first chess playing Beamish. But it’s also worth looking at his sister, usually known as Olive, suffragette, communist and Cambridge graduate; and not the only unexpectedly radical woman you’ll meet in this article.

By 1901 the family had moved to Westbury on Trym, near Bristol, at which point FUB was working as a mechanical engineer, although the family would later run a farm.

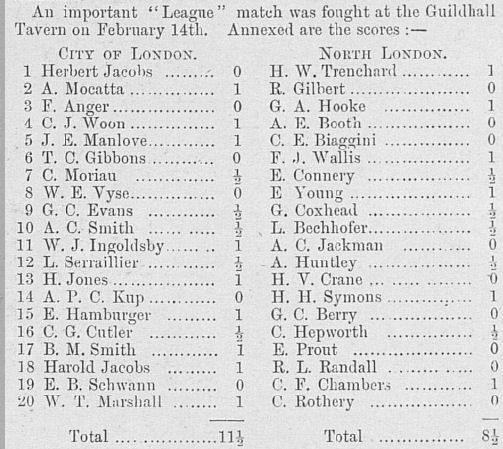

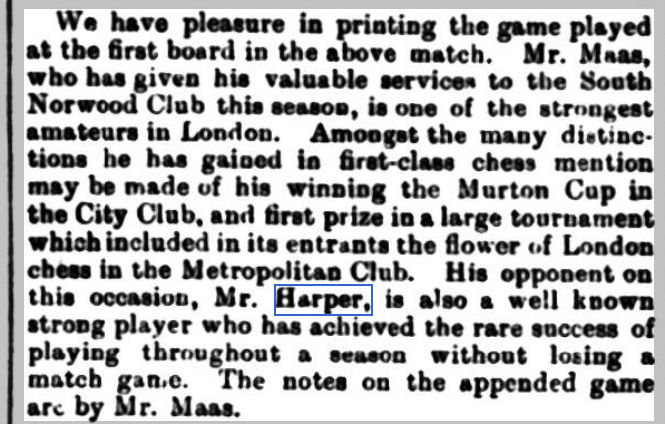

Our first sighting of him at a chessboard is in November 1901, losing his game on a low board in a match in which Bristol and Clifton fielded a ‘very weak team’.

At the age of 24, then, he was very much a novice, taking his first steps in the world of competitive chess. He was soon elected club secretary, and won a game in a simul against Francis Lee. In October 1902 he was one of a group of organisers instrumental in founding a Bristol Chess League. Here was an ambitious young man, very active as both a player and an organiser.

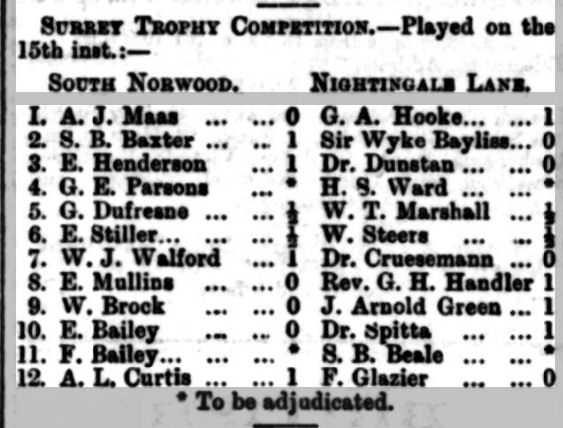

He was improving fast as well, and by 1903 was playing on board 5 for his county team, drawing his game in a match against Surrey.

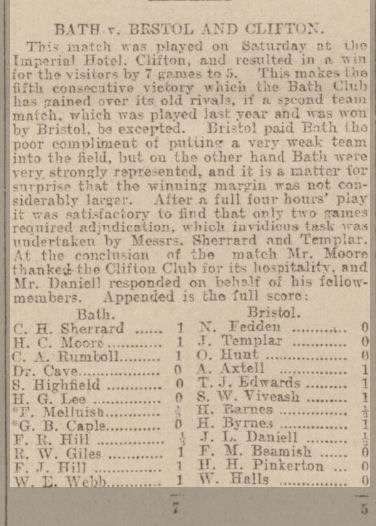

There seems to have been some internal politics going on at the time: it was reported that FUB had resigned from Bristol and Clifton, because he had left the area, but, as well as continuing to play in county matches he was playing for Bristol Chess Club: I don’t know exactly what the relationship was between the two clubs, or indeed between the Bristol Chess League and the Gloucestershire and Bath Chess League, in which this 1906 match took place.

The short game published below was this one, against Bath veteran Alfred Rumboll. Black’s opening repertoire seems to have been sadly deficient. FUB preferred 6. d4 to the Fried Liver Attack, and won quickly against his opponent’s poor defence. Click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up window.

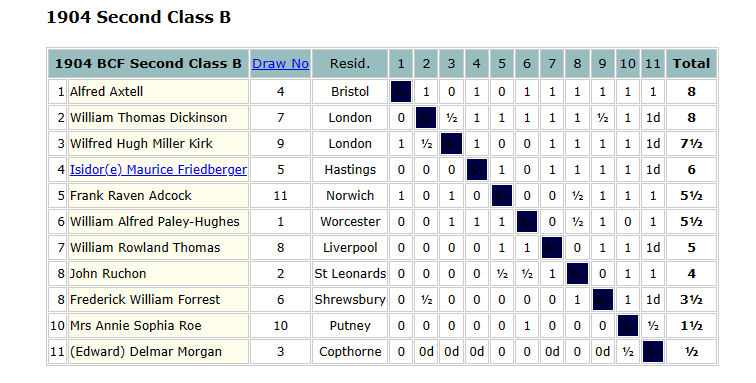

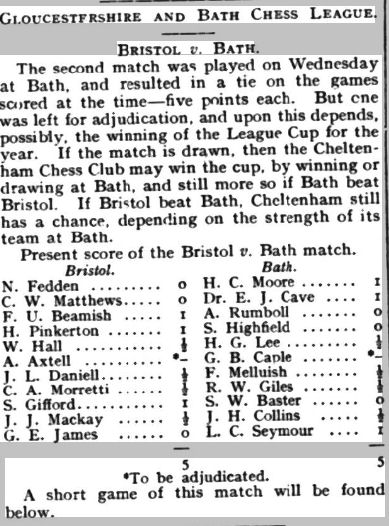

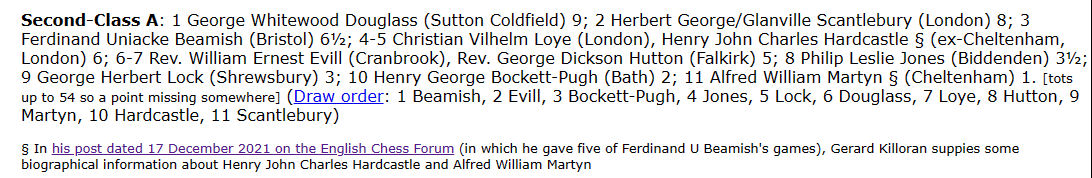

In 1906 he decided to take part in the 3rd British Chess Championships, which took place that year in Shrewsbury. He was placed in Section A of the Second Class Section, scoring a highly respectable 6 points from 10 games.

Confusingly, FUB was also playing for Clifton Chess Club, winning their club championship, and was also taking a high board for his county in correspondence matches, such as this one against Norfolk, where he defended the Evans Gambit against a Norfolk clergyman.

By this time, he was also playing a lot of correspondence chess, not only for Gloucestershire, but also for Ireland and in their national correspondence championship. In this game from a county match Ferdinand gains control of the centre against his opponent’s rather feeble opening and launches a rapid kingside attack.

In 1911 he reached the finals of the county championship, losing the play-off against the ill-fated Samuel Walter Billings.

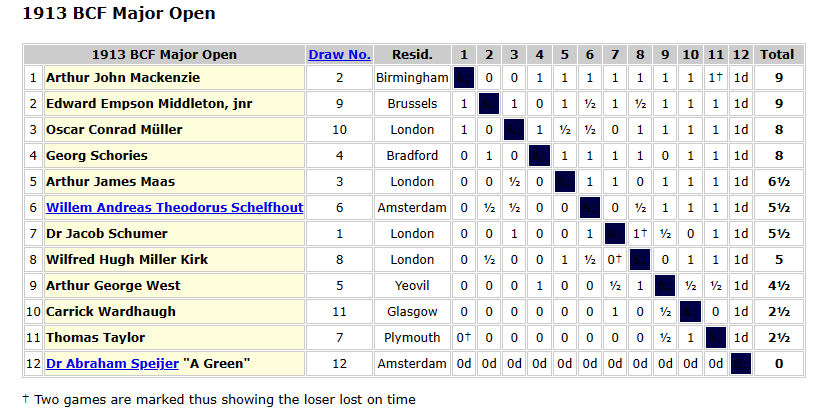

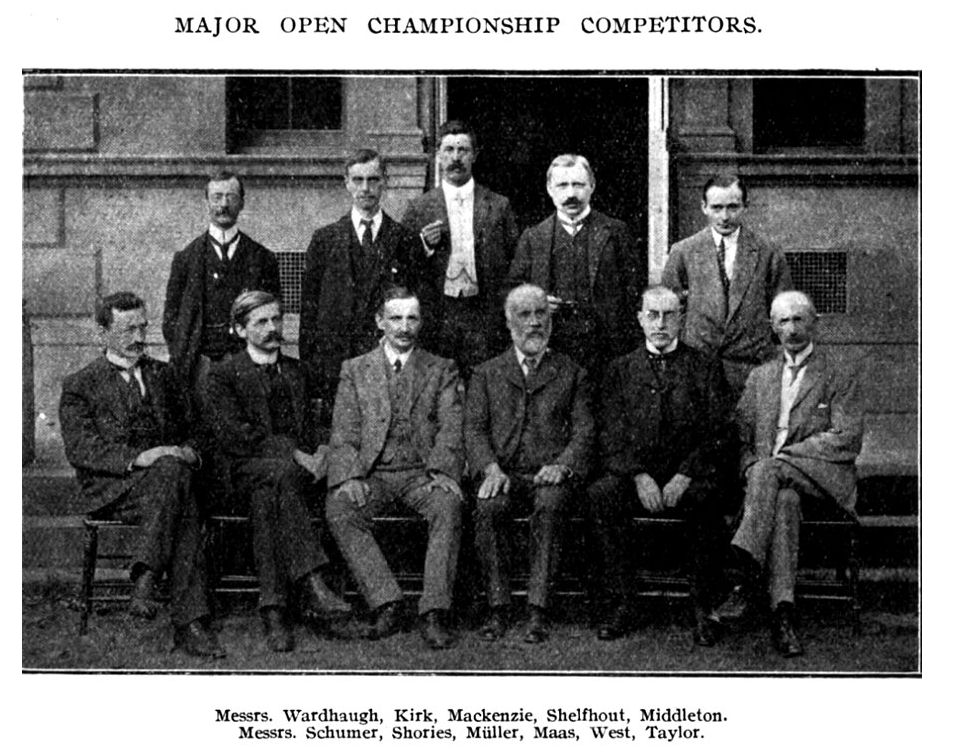

The 1913 British Championships took place in nearby Cheltenham, and FUB returned to the fray, again taking part in the 2nd Class A section, finishing 3rd with 6½/10.

The Cork Weekly News published several of his games: perhaps he submitted them himself so that his friends and relations in his family’s home city would see them.

In this game he quickly gained an advantage against his opponent’s unimpressive opening play.

Superior opening play in this game again gave him the opportunity to demonstrate his attacking skills.

His opponent in this game was, amongst other things, one of the founders of the Gloster Aircraft Company. There’s more about the family firm here.

The dangerous Albin Counter-Gambit was just becoming popular at this time, but Ferdinand knew how to deal with it.

From these games you get the impression of a player much better than his second class status would suggest, with a good knowledge of the latest theory along with a fluent attacking style and tactical ability. But quite often things went wrong, and when they went wrong they went very wrong.

He was on the wrong end of a Best Game Prize winner here against a Danish opponent. As soon as he ran out of theory he blundered into a stock checkmating tactic.

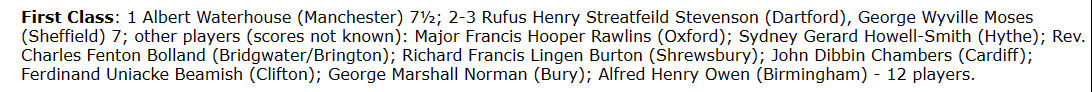

The 1914 British Championships took place in Chester, and this time Ferdinand Uniacke Beamish was promoted to the 1st Class section, but with the UK having declared war against Germany a few days earlier, the players’ minds would have been on other battlefields.

Three games are available: losses to Moses and Stevenson, and this perhaps rather lucky win against George Marshall Norman, who had an impressively long and successful chess career.

He continued playing for Bristol, now with George Tregaskis as a teammate, through 1915, and the last record we have of him is a correspondence game from 1917.

It seems like he gave up chess at this point to concentrate on running the family farm. The 1921 Census found him, living with his elderly mother and a servant, at Dennisworth Farm, Pucklechurch, a village to the east of Bristol. He married in 1924, but it ended in divorce a few years later. In the 1939 Register he was still there, giving his occupation as Dairy Farmer. In 1941 he emigrated to New Zealand, where, according to the 1949 Electoral Roll, he was again working as a Dairy Farmer. He died there in 1957, four decades after his last competitive game of chess.

To resolve the question over the identity of Ferdinand’s London contemporary A/AE Beamish, we need to consider Charles’s youngest son, Alfred, who was born in Cork in 1845 or thereabouts.

We first pick him up in England in 1878, where he marries Selina Taylor Prichard in Hastings. Selina had previously been married to the much older Surgeon General William White, who had left her with a daughter named Jessie Mabel.

Mabel (she preferred to use her middle name) is worth a detour. Despite her military background she was a committed pacifist. Her husband’s name was very familiar to me, given my background in Anglican church music, but may not be to you. Percy Dearmer was a socialist priest best remembered, at least by me, for editing The English Hymnal along with one of my musical heroes, Ralph Vaughan Williams. Their elder son, Geoffrey, was a poet who lived to the age of 103.

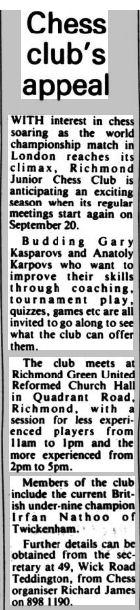

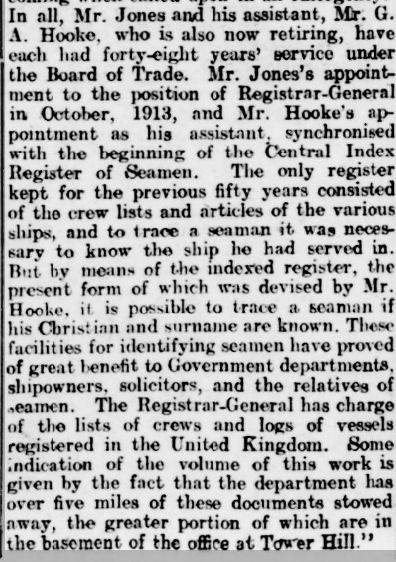

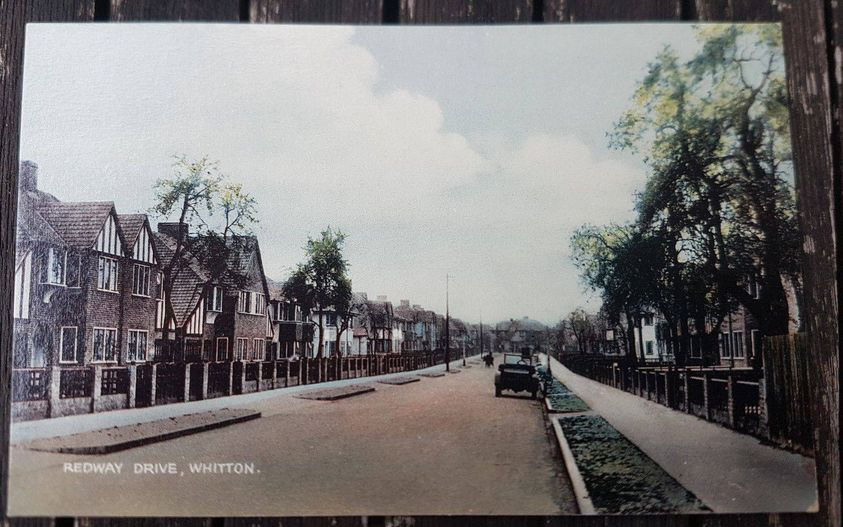

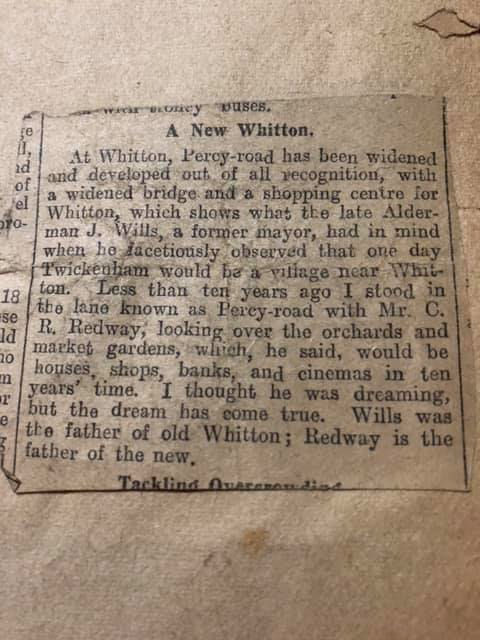

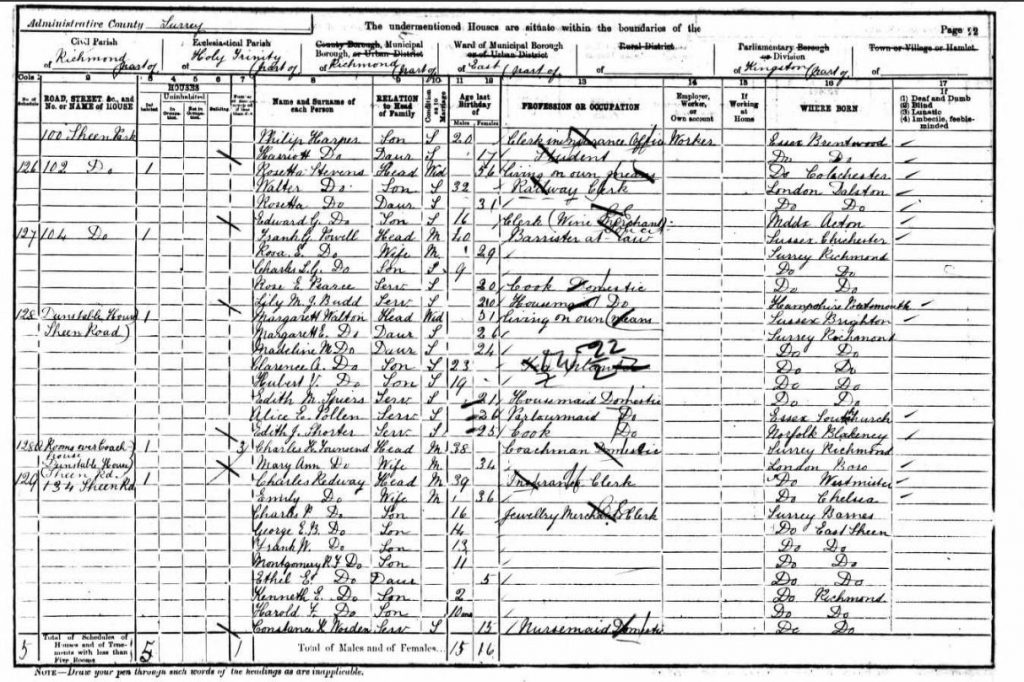

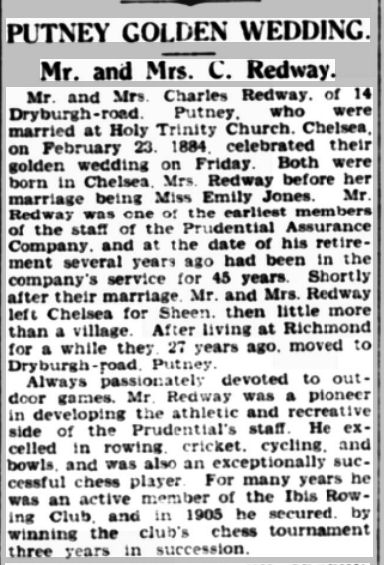

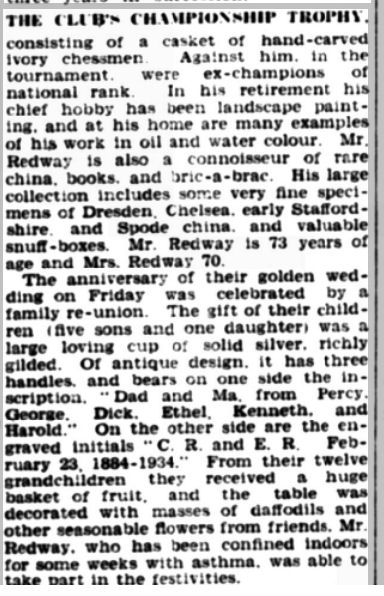

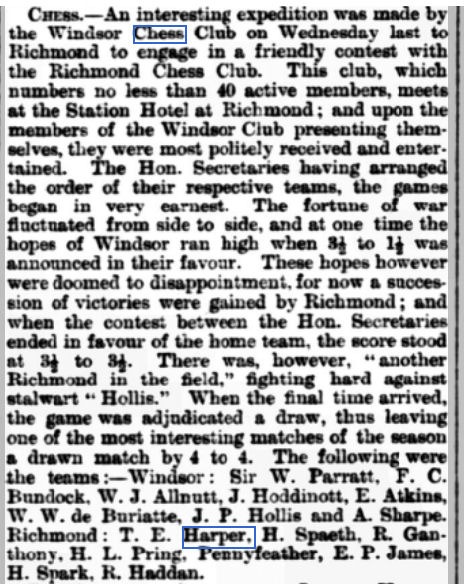

Alfred was a barrister and solicitor, and after his marriage he and Selina settled in Richmond, where their two sons, Alfred Ernest (1879) and Edmund Arthur (1880) were born. We can pick them up in the 1881 census at 13 Spring Terrace, Marsh Gate Road, Richmond. Spring Terrace, now in Paradise Road, is an impressive row of Georgian houses. The family were clearly very well off, employing four servants, a housemaid, a nurse, an under nurse and a cook.

By 1891 they’d moved to 115 Church Road, a large house near the top of Richmond Hill, just as you approach St Matthias Church. Alfred senior, Selina, Mabel and their older son were there. It’s not clear where the younger boy was: perhaps away at school.

Alfred and Selina had decided that their sons should be educated at Harrow as day boys, and so, a few years later, they moved up to North West London, although it would seem that they also retained possession of their Richmond house. Alfred senior died in Harrow in 1898, and the 1901 census found Selina and her sons there, along with two servants. Neither of their sons had a job: the family was so well off that they had no need of paid employment.

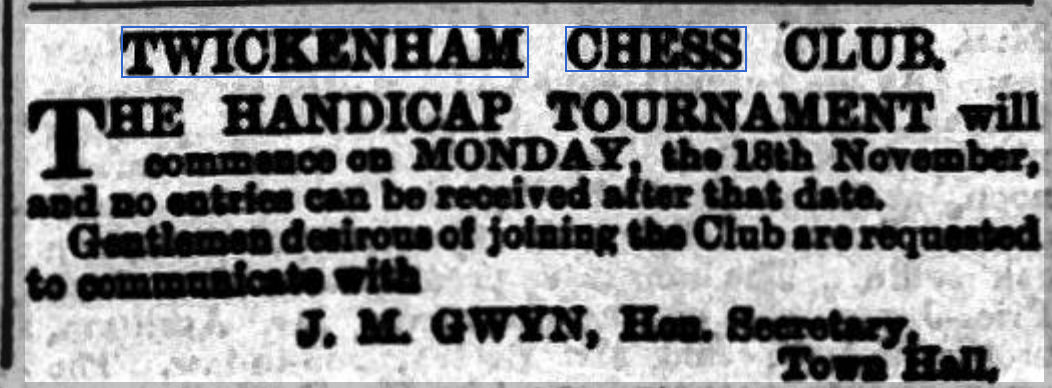

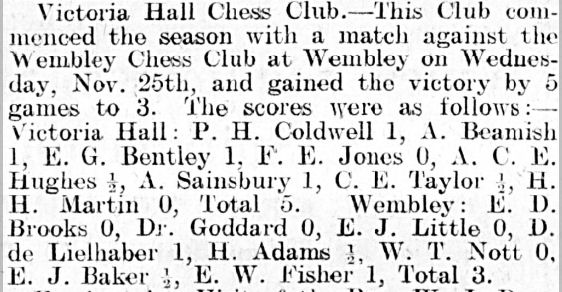

We first spot A Beamish as a Harrow chess player in 1903.

Much more recently, Victoria Hall, in the town centre and very close to where they were living, was, for many years, the home of the current Harrow Chess Club. I played several Thames Valley League games there myself.

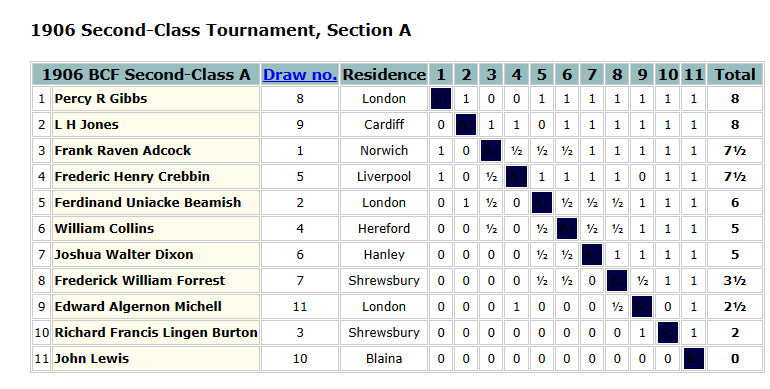

At this point we need to look at the controversy concerning the identity of this A (or sometimes AE) Beamish. It seems, on the surface, not unreasonable to assume this was Alfred Ernest, but there were other pointers suggesting it was really Edmund Arthur. There has also been a suggestion that it might have been an Arthur Edmund Beamish, perhaps a distant cousin, who was living in Islington at the time. Given that our brothers were round the corner from this sighting, though, this seems unlikely.

The older brother, Alfred Ernest Beamish, took up the game of tennis, later becoming one of the leading English players of his day, an opponent and occasional doubles partner of none other than Sir George Thomas, an author and administrator. His career was interrupted by the First World War, in which he served as a Lieutenant in the Royal Army Service Corps, so he would have been involved in administrative work. Some secondary sources refer to him as a Captain. Here, you can see his wife offering some tennis tips.

The younger brother, Edmund Arthur Beamish, by contrast, was a soldier. Although he was without employment in 1901, he had previously signed up to fight in the Second Boer War, serving as a Lieutenant in the 28th Battalion Imperial Yeomanry, and would rejoin, also serving, like his brother, in the First World War, where he reached the rank of Captain in the 1/18th Battalion London Regiment.

To identify the chess player for certain, we need to spin forward to the year 1912. AEB took part in the Australasian Open Tennis Championship in December that year, reaching the finals of both the singles and doubles, leaving London on the Themistocles on 12 September, and arriving back home on board the Omrah on 14 March 1913.

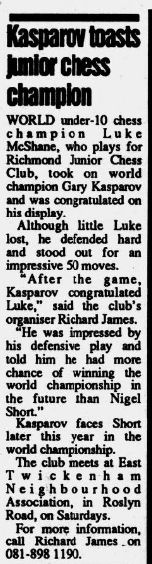

Meanwhile, the chess playing AB was competing in the City of London Chess Championship at the same time, which tells us that the tennis player couldn’t possibly have been the chess player.

There’s corroborative evidence as well: both brothers, like their half-sister, preferred to use their middle names. When EAB joined the army in 1899 he gave his name as plain Arthur, and when AEB returned from his tennis tournament, his name on the register of passengers was A Ernest Beamish.

So we’ll assume from now on that EAB (not AEB) was the 1903-1914 chess player referred to in the press as A Beamish or AE Beamish.

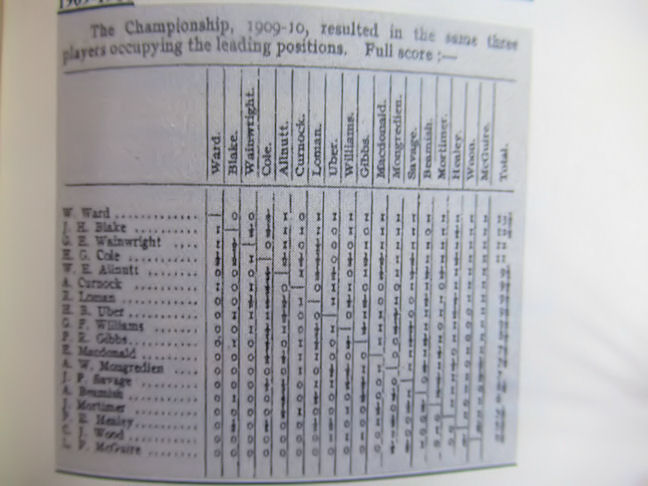

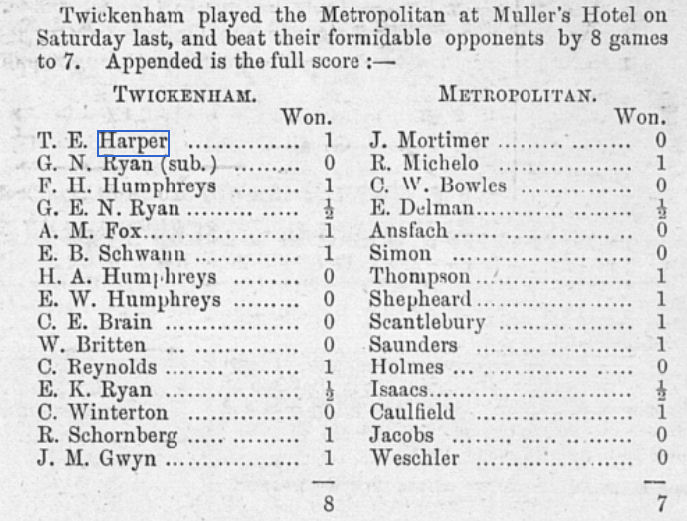

Returning to 1904, in February that year Emanuel Lasker gave a simultaneous display against members of the Metropolitan Chess Club at the Criterion Restaurant in London, allowing consultation. He won 19 games and drew 1, playing black against Messrs Beamish and Lowenthal in consultation. This must have been our Mr Beamish: his consultation partner was probably Frederick Kimberley Loewenthal.

It seems Lasker missed a few chances for an advantage here. As always, click on any move for a pop-up window.

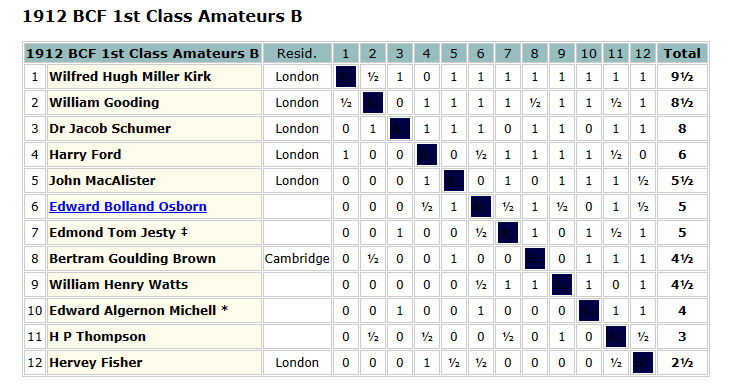

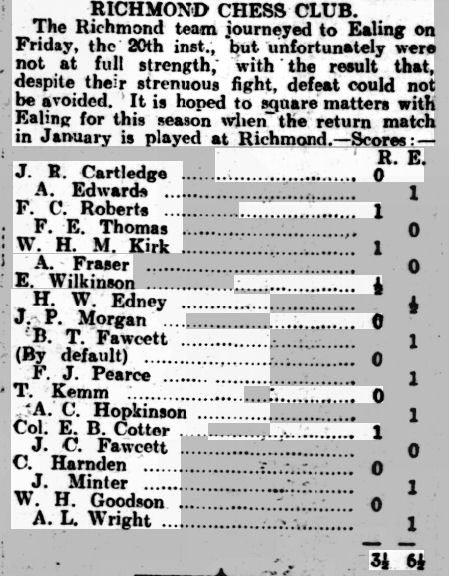

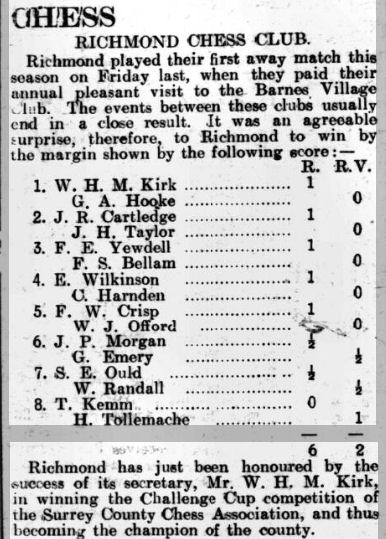

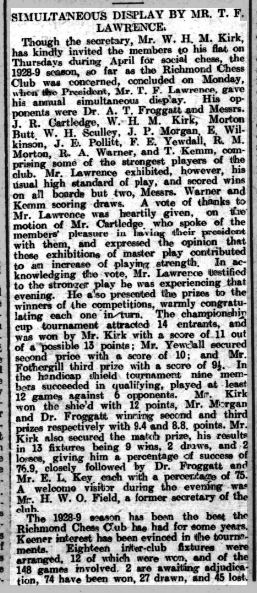

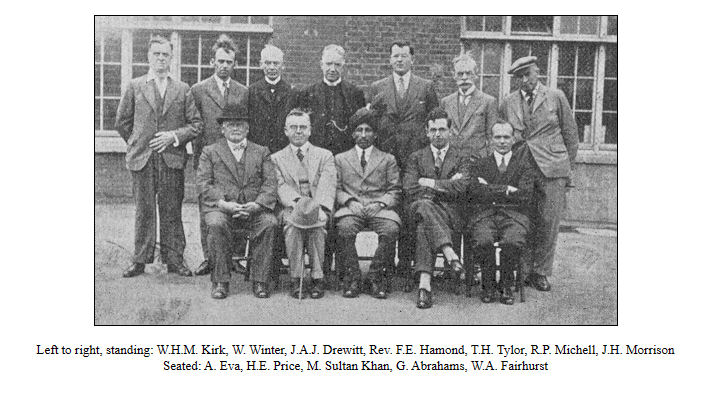

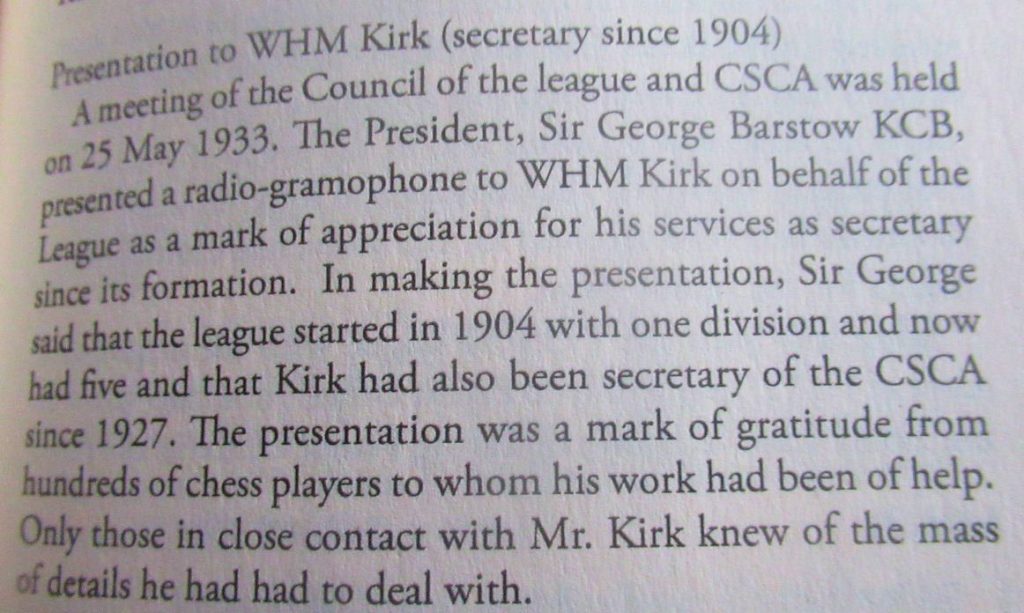

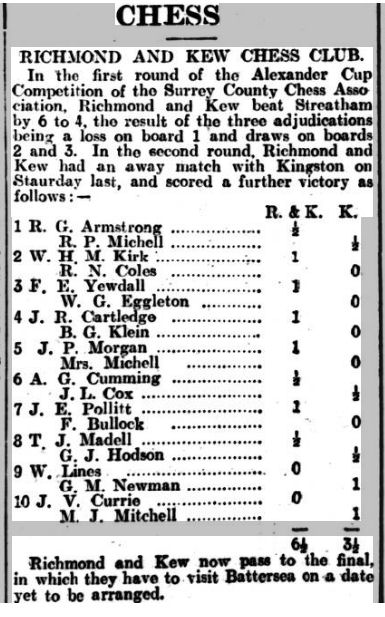

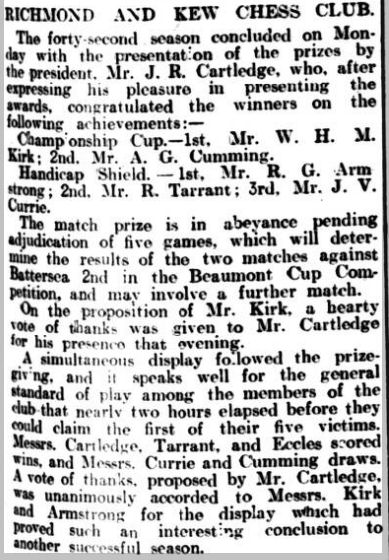

In 1905 he took part in the Second Class Open section of the Kent County Chess Association tournament at Crystal Palace, scoring 5 points for a share of 4th place. Our friend Wilfred Hugh Miller Kirk tied for first place.

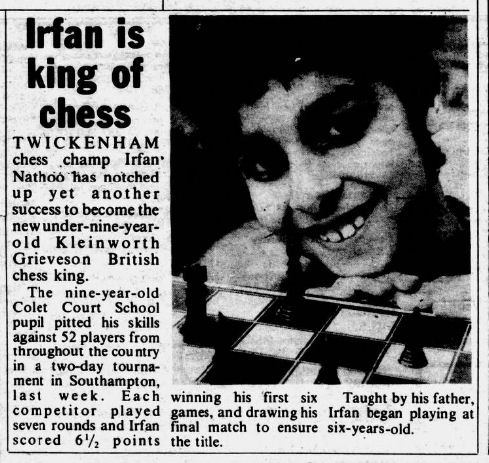

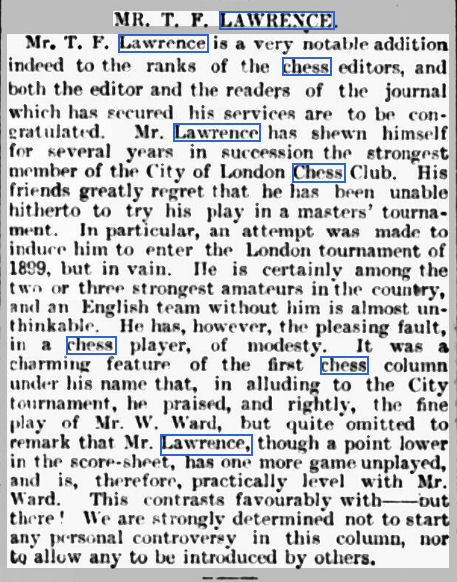

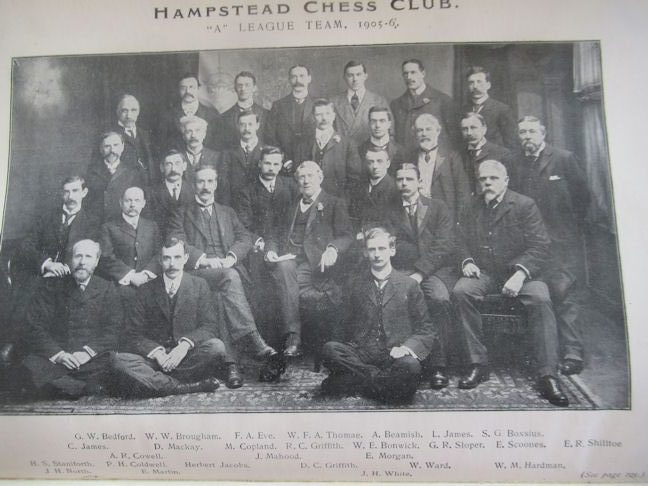

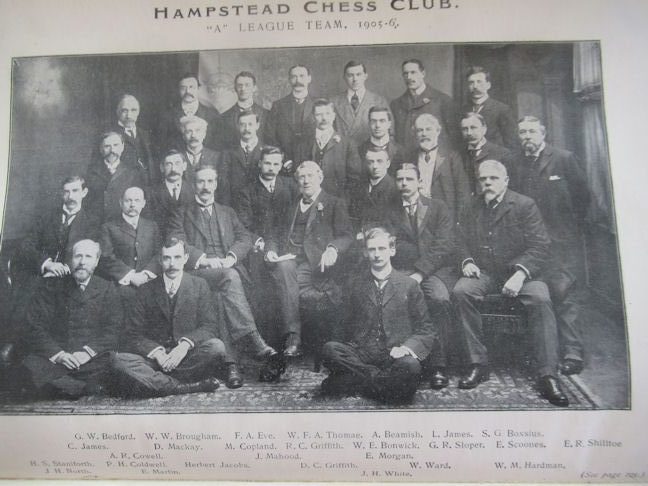

Here is is, third from the right in the top row, playing for Hampstead in 1905-06.

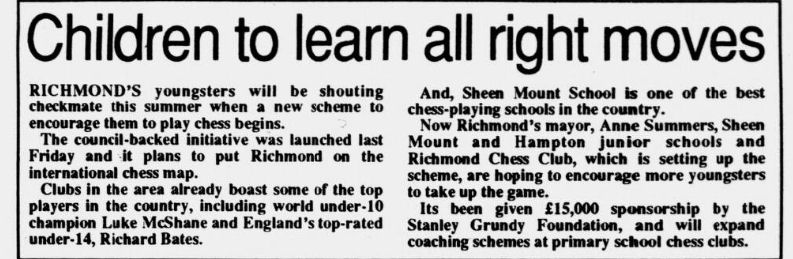

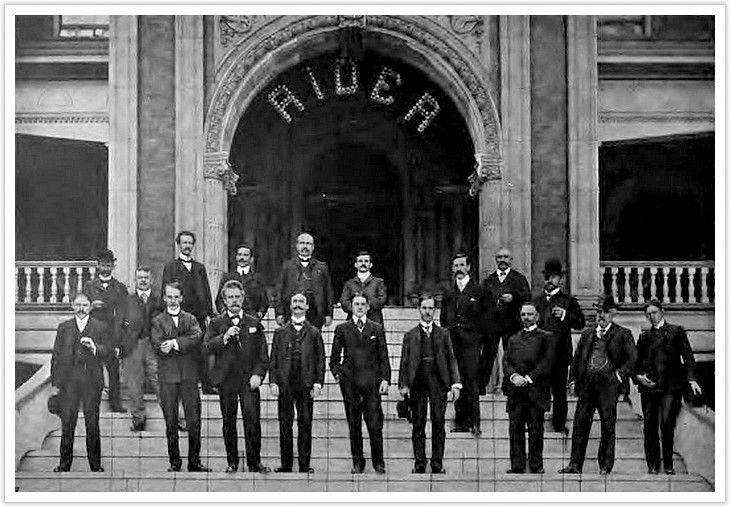

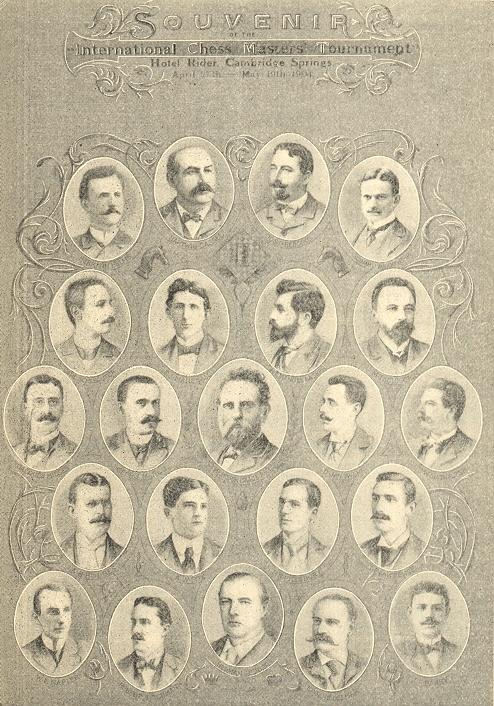

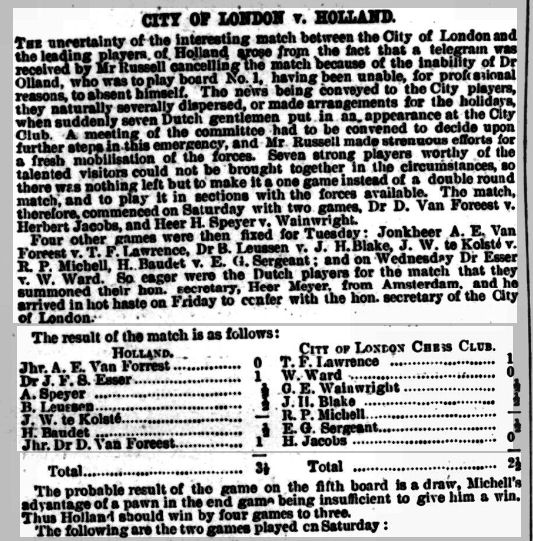

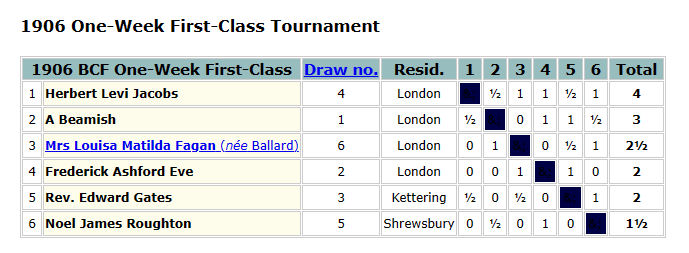

In 1906 he competed, along with his cousin Ferdinand, in the British Chess Championships in Shrewsbury. He was unable to stay for the full fortnight, so was placed in the One-Week First Class section.

A pretty good performance: drawing with the very strong Herbert Levi Jacobs was no mean feat.

This ‘short and sweet’ game, against an opponent who understandably preferred to remain anonymous, was published later the same year. At this time he seemed closely involved with four chess clubs: Harrow, Hampstead, Metropolitan and City of London.

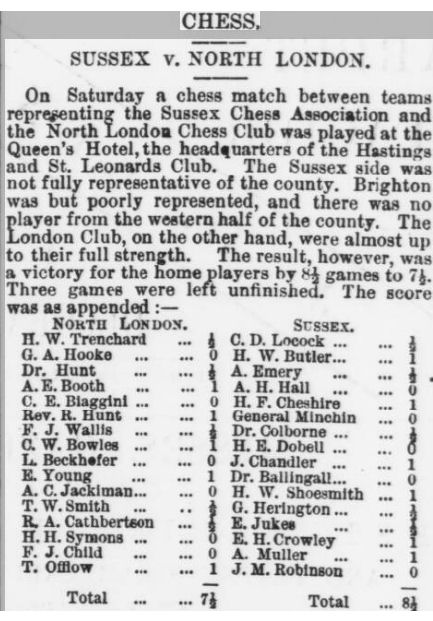

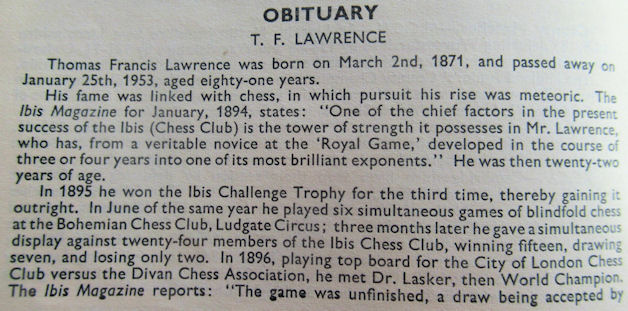

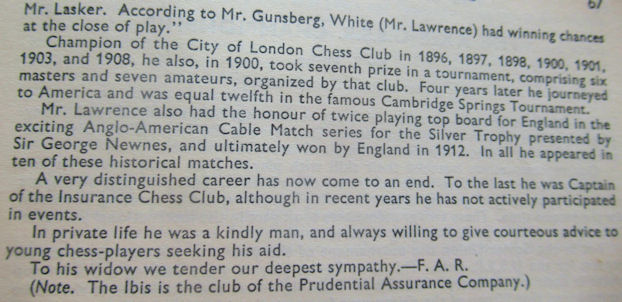

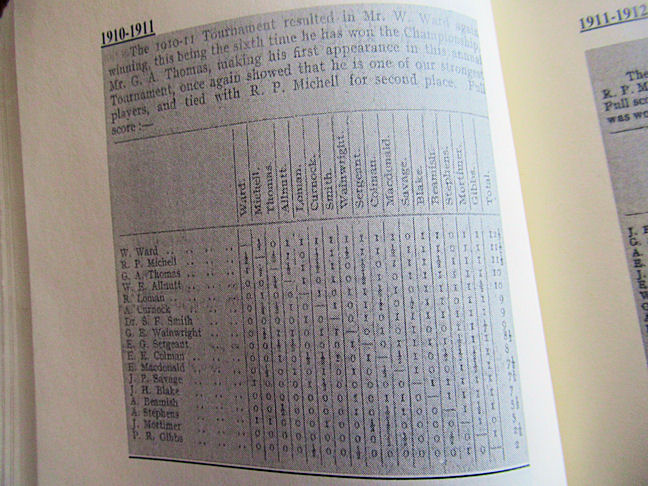

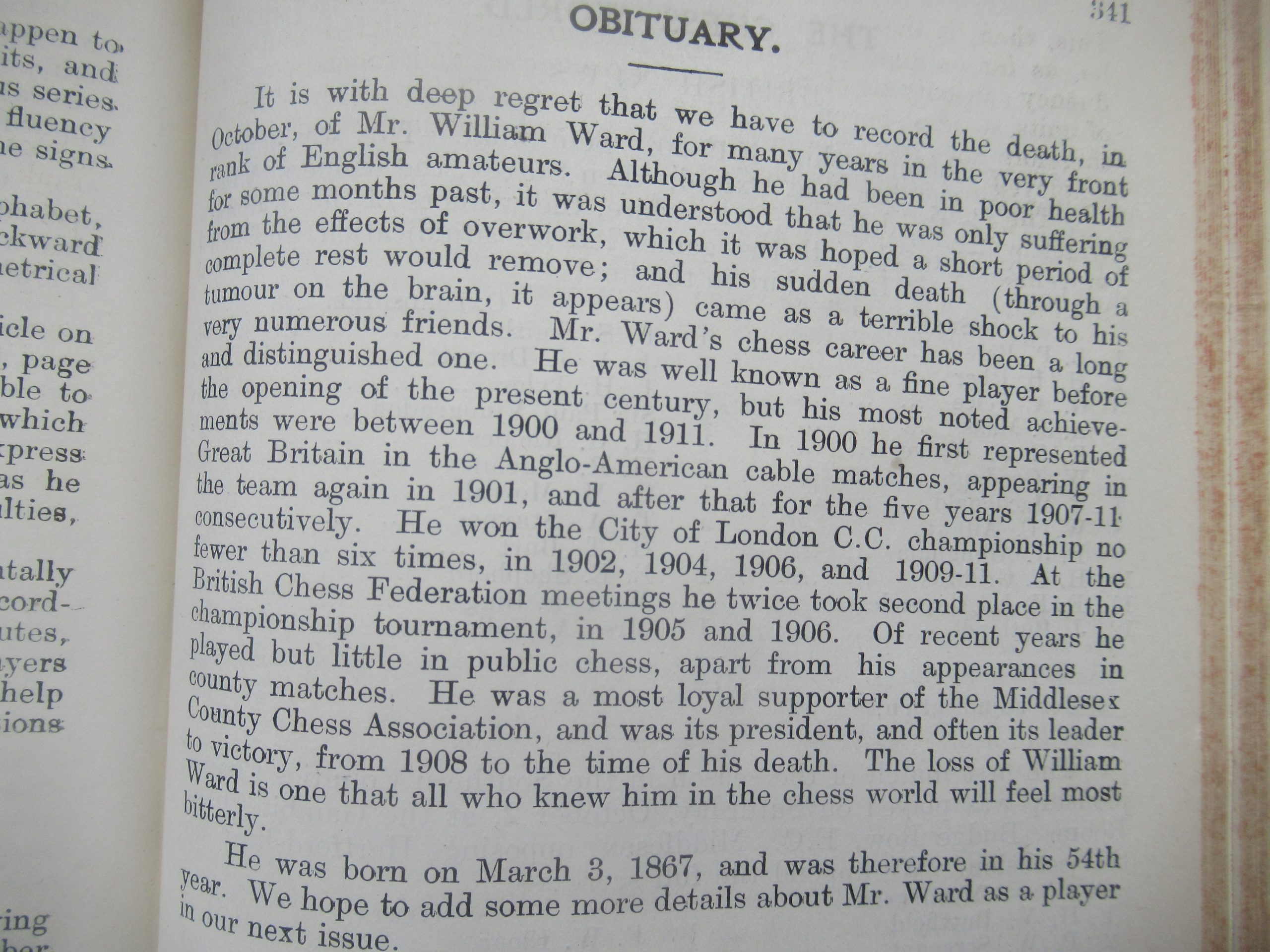

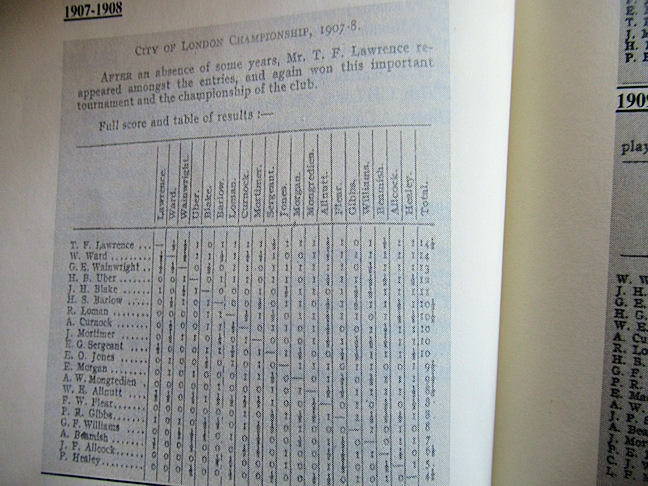

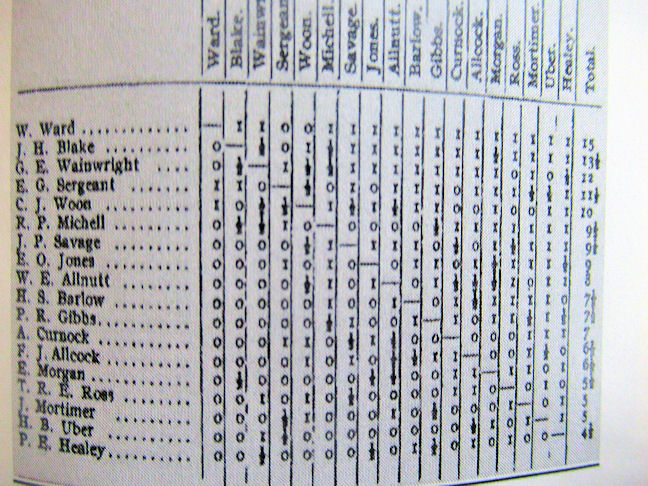

Edmund Arthur Beamish took part in the prestigious City of London Club Championship on four occasions, but without conspicuous success. In 1907-08, 1909-10 and 1910-11 he finished down the field, but with occasional good results against master opponents. In the 1912-13 Diamond Jubilee Tournament, which had four preliminary sections, he again struggled.

In this game from the 1910-11 event he scored a notable scalp, although it must be said that Wainwright was playing well below his usual strength in the tournament.

In this game from the same event Beamish had rather the worse of the opening, but managed to turn the tables and, although he missed a neat mate in 3, brought home the full point.

His opponent in this quick win finished in last place.

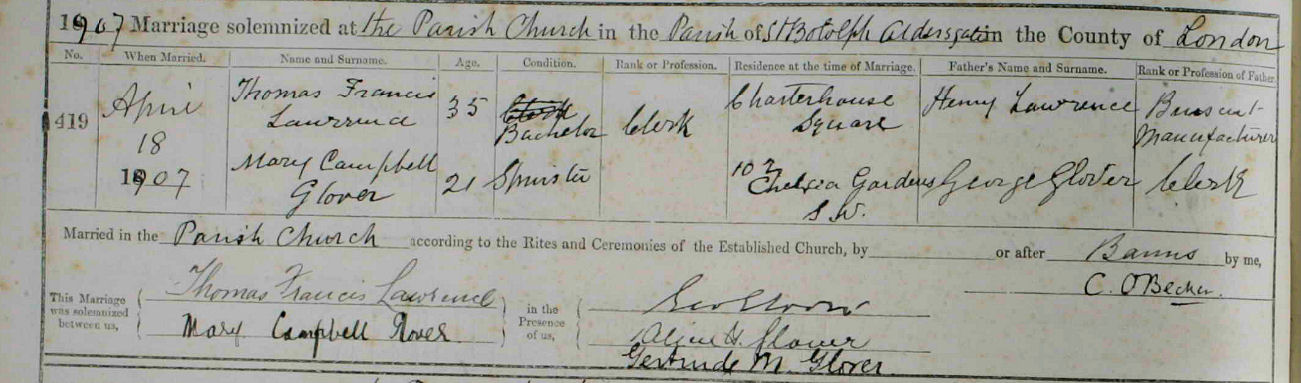

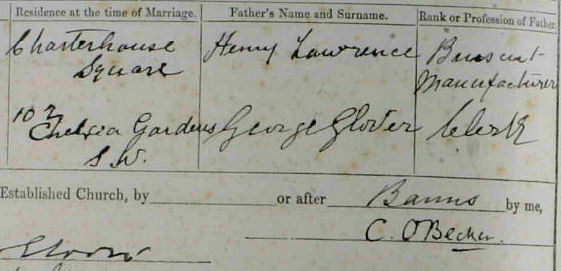

In early 1911 he married Edith Ada Jenner, and, by the time of the census they had set up home at 10 Fairholme Road, West Kensington. He described himself in the census is ‘late Lieutenant Imperial Yeomanry’. They would go on to have two children, Desmond (1915) and Selina (1918), both born in Hastings.

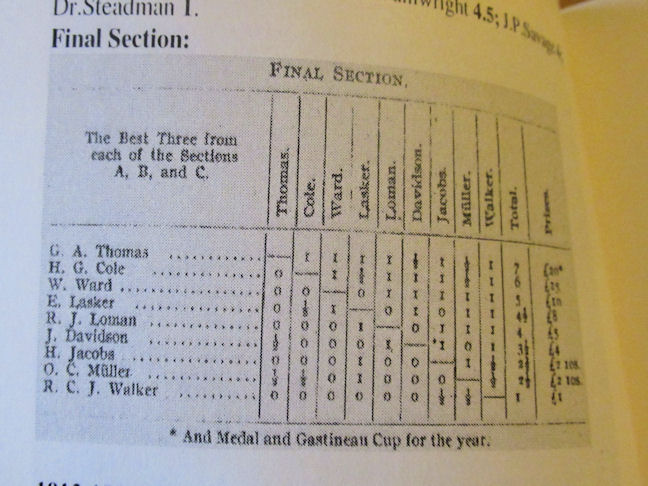

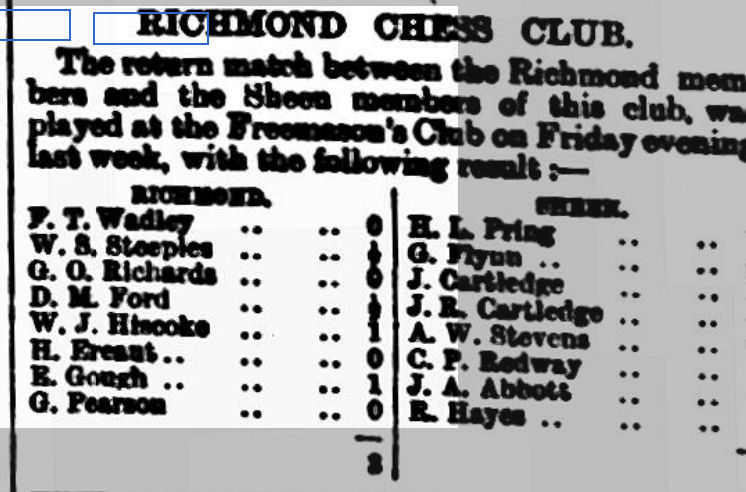

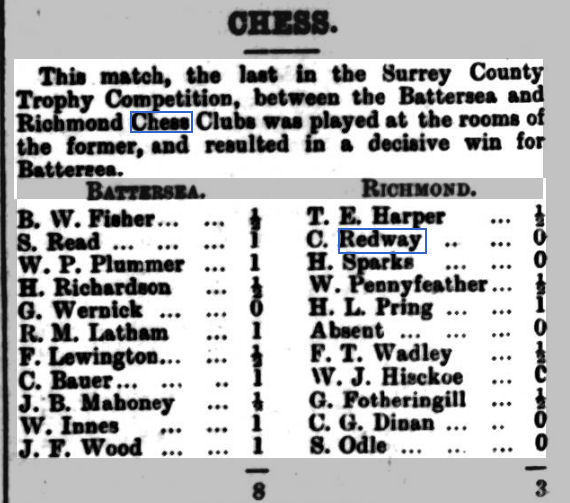

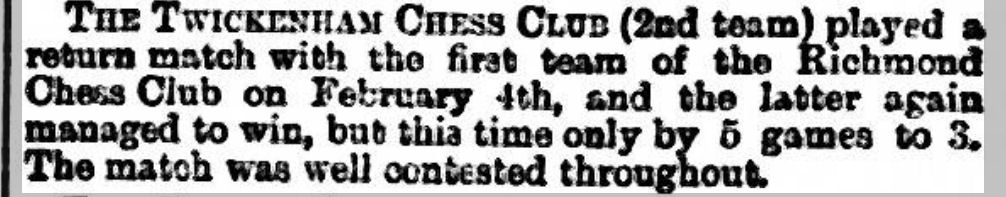

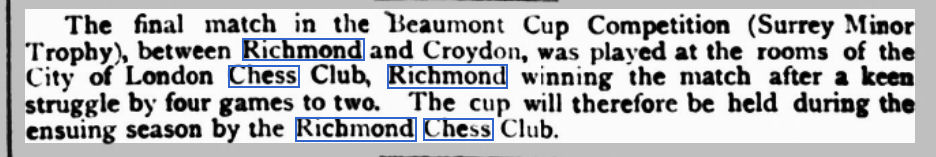

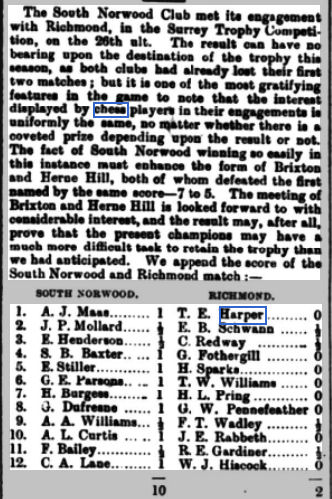

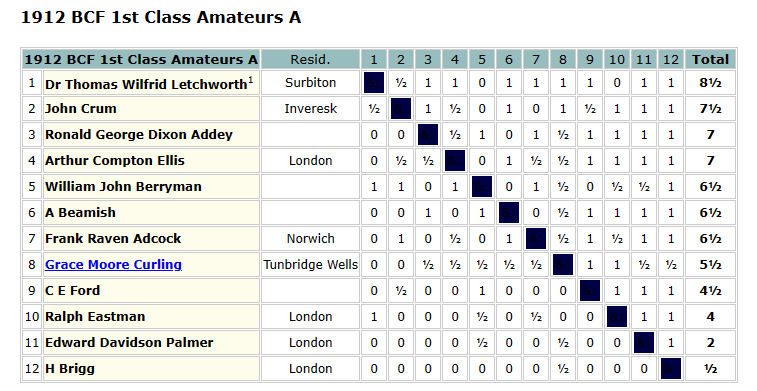

In 1912 the British Championships took place in his home town of Richmond, and he entered the First Class A section.

A pretty good result, even though his loss against Arthur Compton Ellis was awarded a Best Game Priz.

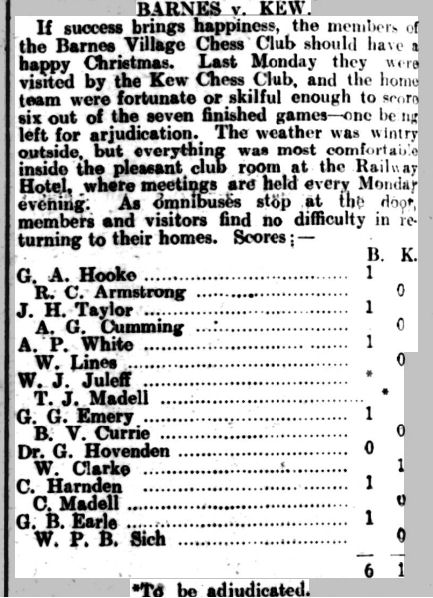

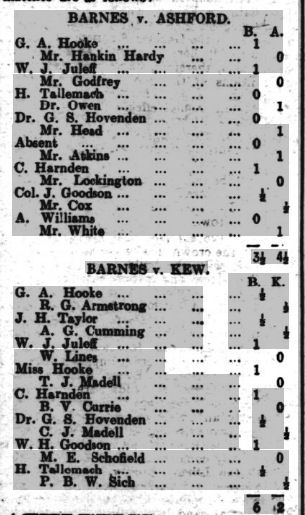

By now he’d transferred his allegiance from Harrow and Hampstead to his local club, West London.

But soon war intervened, and, now with two young children to support, he didn’t return to the chessboard.

By the time of the 1921 census he was visiting his elderly mother, who was living in the family home back in Richmond. He now had a job, working as an accounts clerk for R Seymour Corporate Accountant. There were three servants in residence, a nurse, a cook and a parlourmaid. His wife and children, meanwhile, had moved in with her elderly parents in Hastings. Had their marriage broken up, I wonder.

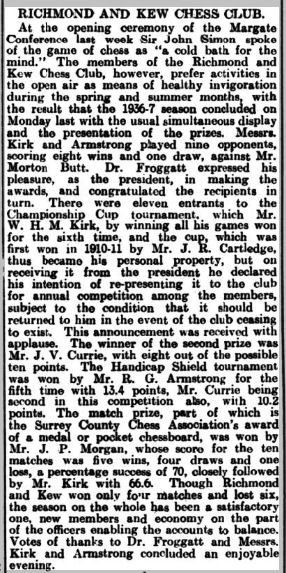

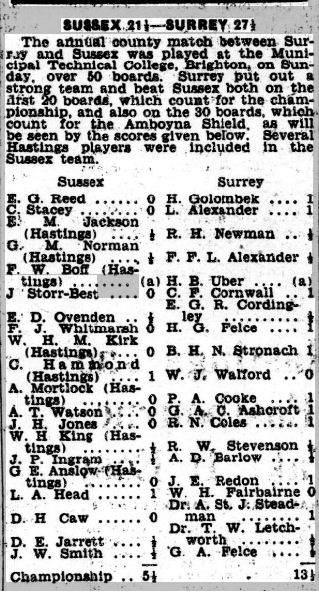

And then, in 1935, he made an unexpected comeback. Over the next few years he played regularly for Middlesex in county matches, and in congresses in Hastings, London and Margate, often with some success. It seems that a twenty year break and advancing years didn’t affect his chess strength.

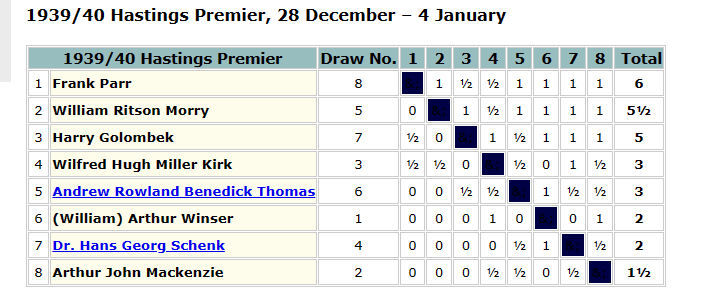

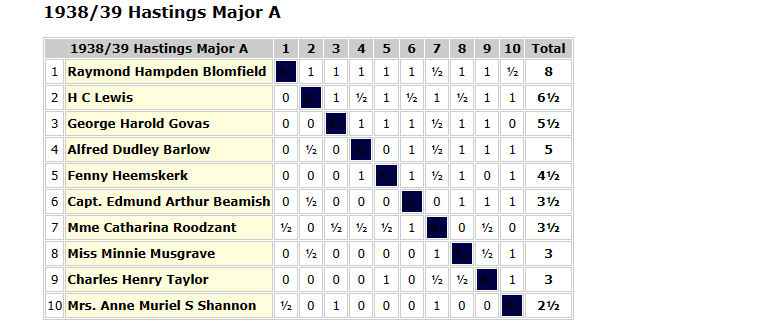

I’ve only managed to locate one game from these years, a loss against the Dutch Ladies’ Champion Fenny Heemskerk.

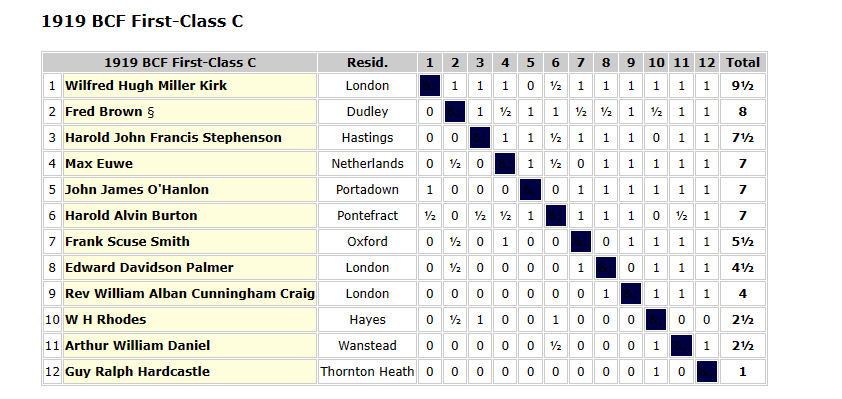

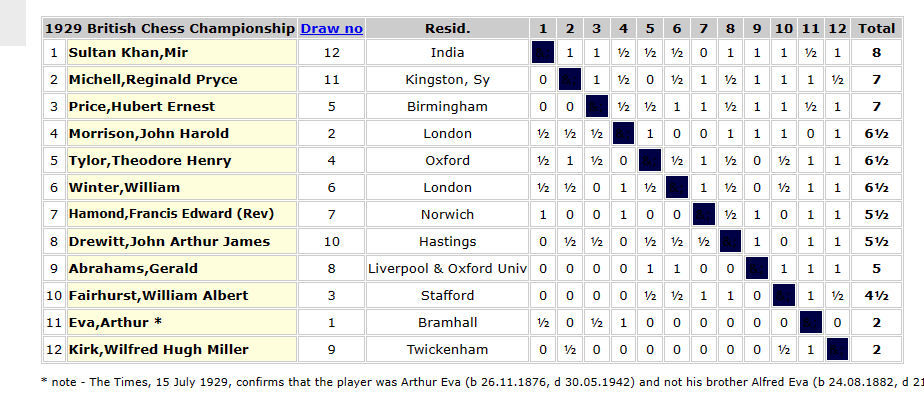

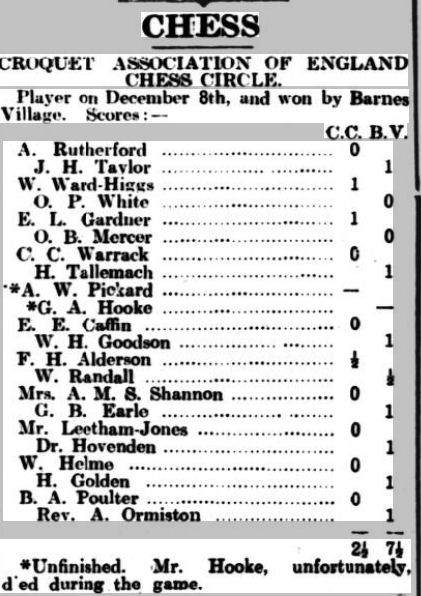

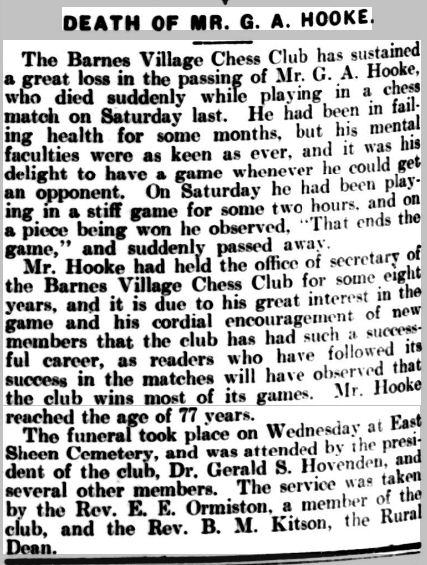

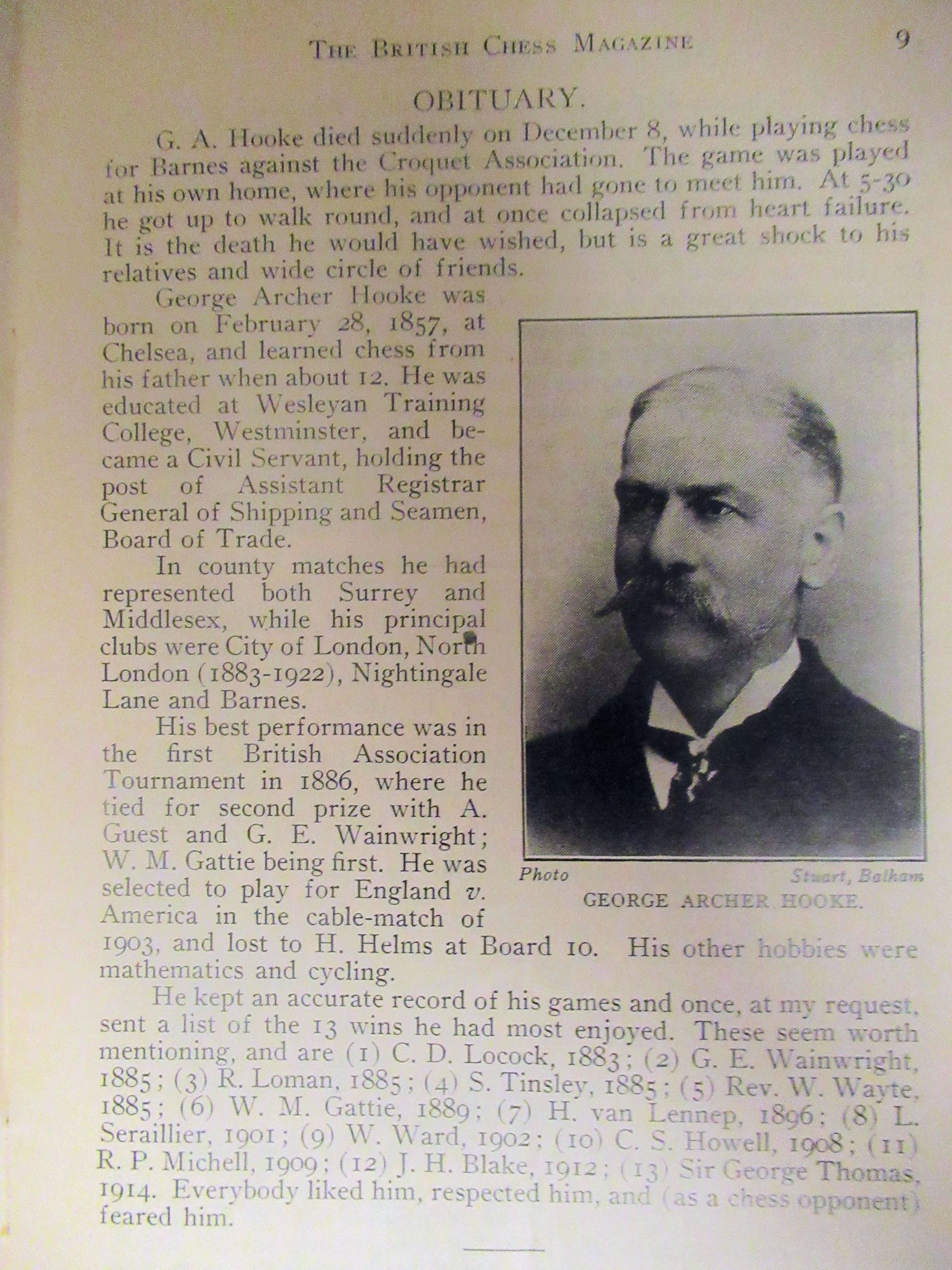

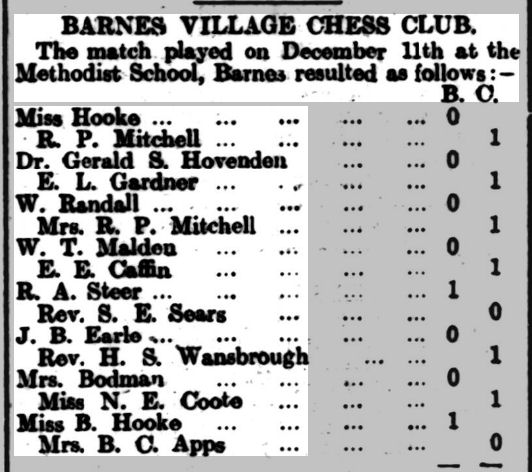

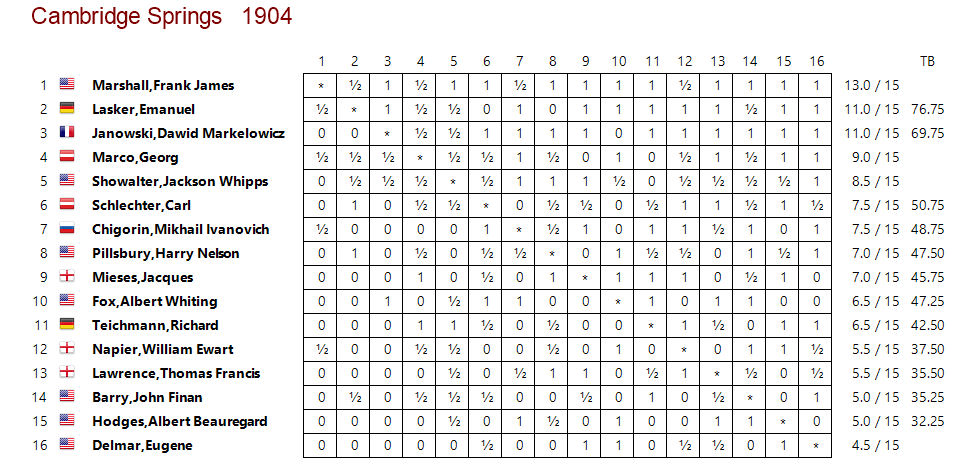

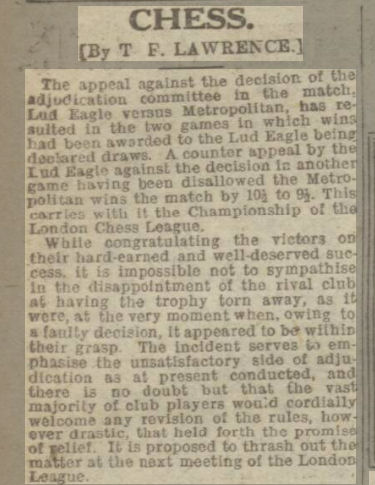

Here’s the crosstable from that event.

The 1939 Register found EAB, his wife and daughter living together in the old family home, 115 Church Road, Richmond. He was described as a retired army captain. They had no domestic staff and some of the rooms had been let out to others, so perhaps they weren’t as well off as they had been.

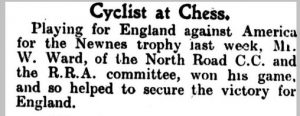

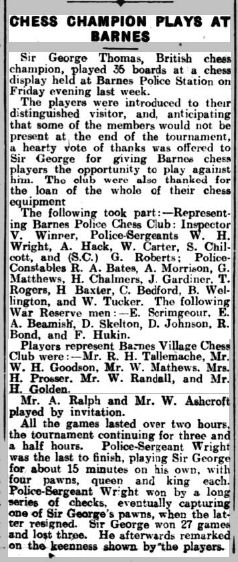

Although he was living in Richmond and very active again in both county and tournament chess, he doesn’t seem to have joined any of the clubs in our Borough. He did, however, make a guest appearance at Barnes Police Station in 1941, playing in a simul against his brother’s old tennis chum Sir George Thomas (they had played out a draw in the City of London Club Championship 30 years earlier).

In the same year he joined West London Chess Club, which, while most clubs had closed, was flourishing with an impressive range of members and activities. EAB played regularly in matches against a variety of opponents as well as competing in their regular lightning tournaments and other internal competitions.

Here’s a club photograph from 1943. Beamish is second from the right in the front row.

In this game he played on Board 1 against Upminster: his opponent was an undertaker by profession. The West London Chess Club Gazette describes it as ‘an example of the fatal consequences of a premature attack’, but Stockfish points out that White missed a win on move 11.

He returned to tournament play after the war, taking part in the Major A section at Hastings in 1945-46. With the London League returning to action, he played 12 games for West London, scoring 6 wins, 4 draws and only 2 losses.

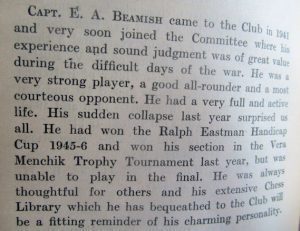

Shortly afterwards he was taken seriously ill, and died on 13 October 1946, at the age of 66. His club published a fine tribute to one of their strongest and most respected members.

I wonder what happened to his extensive Chess Library. Does anyone at West London Chess Club know?

EdoChess gives his rating before WW1 as just below 2100, which seems reasonable: a strong club player who could score the occasional result against master standard opposition. His cousin Ferdinand was perhaps slightly weaker, although he played some highly entertaining chess.

There’s one more mystery, there was an A Beamish playing for Devon in the years leading up to World War 1, mostly by correspondence but occasionally over the board. I can’t find any Devon connection for him, but his Uncle Albert, about whom very little seems to be known died in Devon in 1920. Was it him? Who knows?

And who knows where my next Minor Piece will take you?

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

English Chess Forum (contributions from Gerard Killoran and others)

West London Chess Club Gazette

BritBase (John Saunders)

EdoChess (Rod Edwards)

YouTube