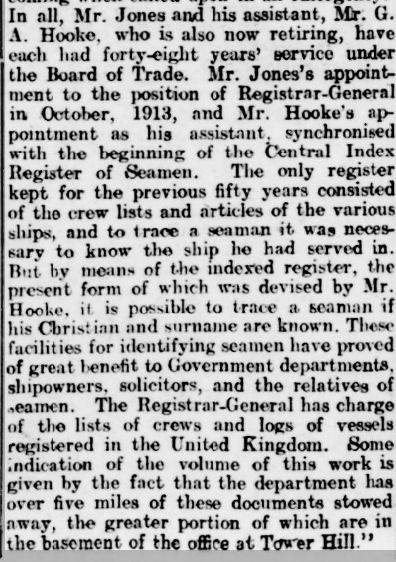

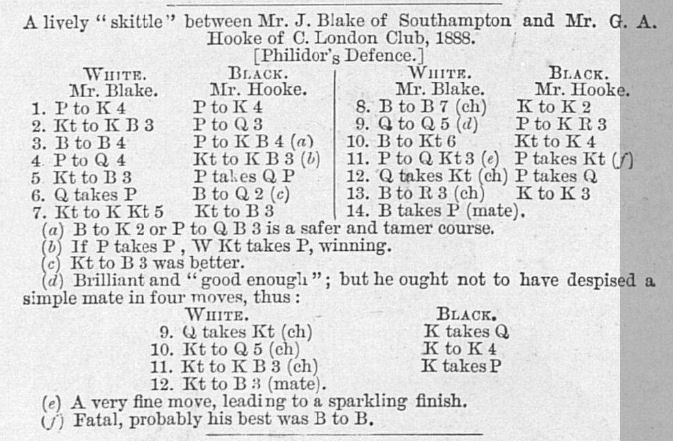

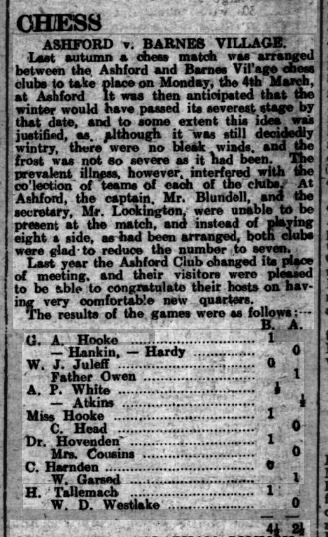

In the last two Minor Pieces (here and here) you met George Archer Hooke. Mention was made of his sister, Alice Elizabeth Hooke, who was also a competitive player: not as strong as her brother, but of more historical significance.

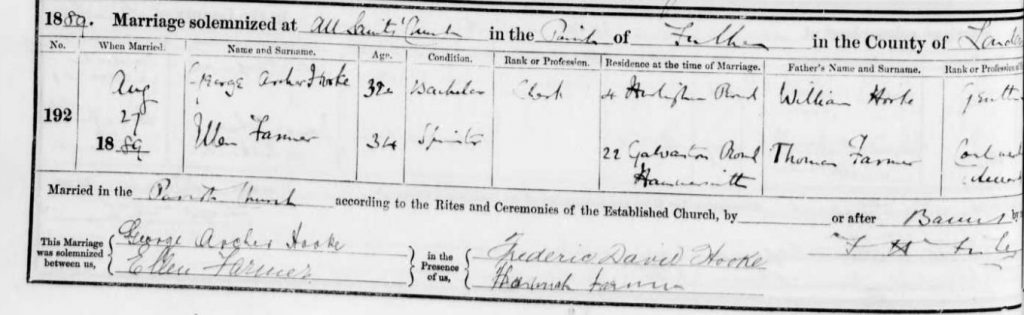

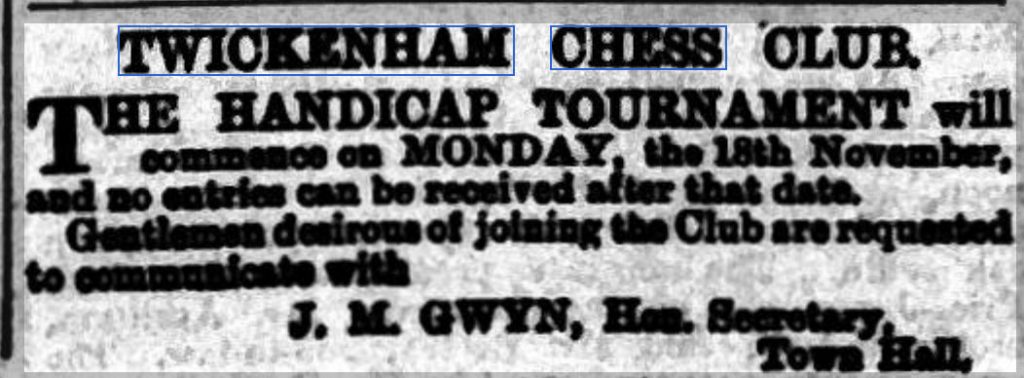

Alice was born on 20 October 1862, and, as expected was living at home in 1871 and 1881, although no occupation is listed for her on the 1881 census. By 1891, still at home, she was, like several of her siblings, working as a clerk (the details aren’t very legible). Presumably she, like George, had learnt chess from her father, but in those days chess clubs weren’t seen as places for women. Some clubs, like Twickenham, specified in their advertisements that they welcomed ‘gentlemen’. No plebs, and no ladies either.

But views on the role of women in society were changing. If men could have chess clubs, why couldn’t women?

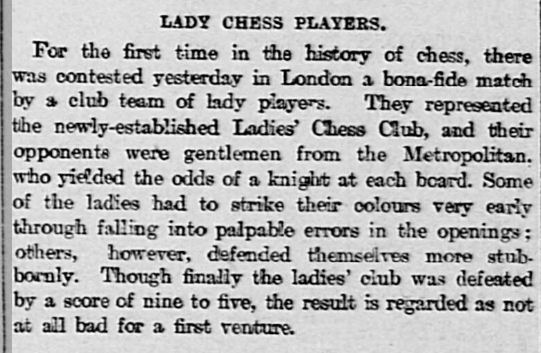

Well, it certainly wasn’t the first Ladies’ Chess Club in England, and portrait painter Edith Mary Burrell (1858-1906) wasn’t all that young either, but the club, as you’ll see, would become very popular and successful.They soon found a venue in the Strand opposite Charing Cross Station and, by May, were playing their first match.

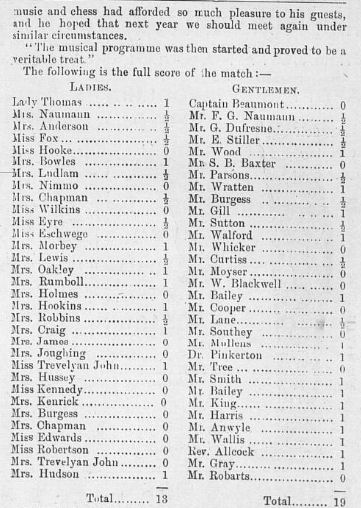

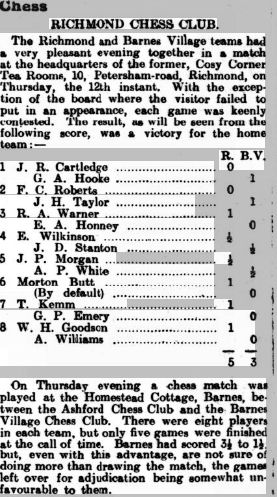

Alice, a keen social chess player, had wasted no time in joining, playing top board in this match. As you’ll see, the gentlemen of the Metropolitan club, as well as giving knight odds, were only their third team players, which suggests that most of the ladies were, at this point, not very strong players.

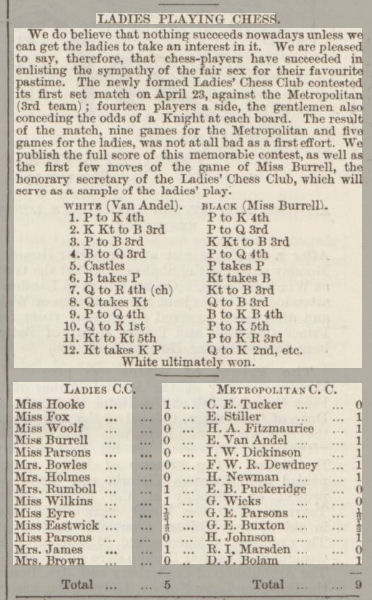

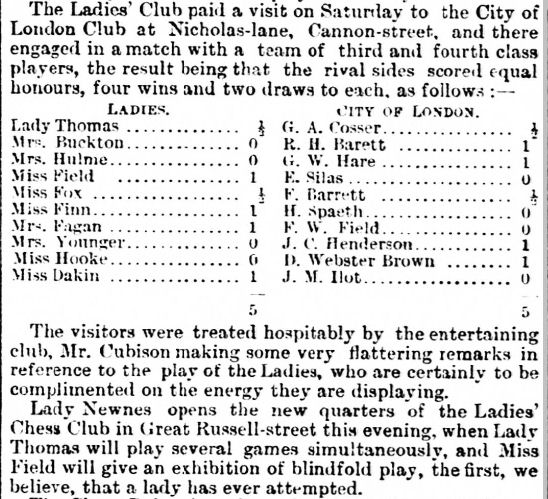

The following month their first Annual General Meeting took place. Miss Alice Elizabeth Hooke was elected Hon Secretary and Treasurer.

Most importantly, Mrs Rhoda Bowles was elected match captain and tournament secretary. All chess clubs are only as good as their organisers, and, in Rhoda Bowles, they had an organiser and publicist of exceptional energy and talent, with, I’d imagine, Alice Hooke doing the backroom work with considerable efficiency.

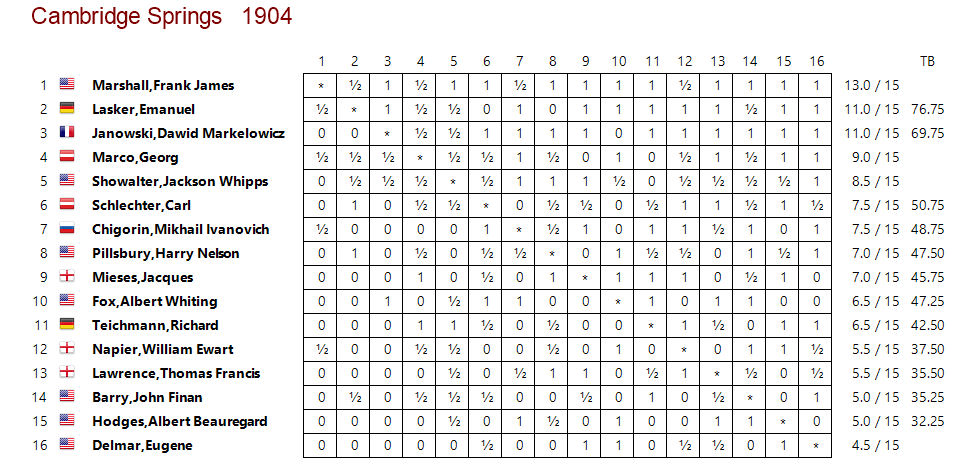

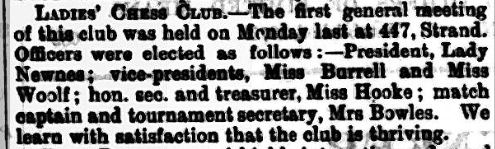

The club continued to thrive, offering a bewildering whirl of activities: internal tournaments, simultaneous displays, including one from Harry Nelson Pillsbury, fresh from his success at Hastings, and matches against other clubs. By October, with their membership having grown to 75, they found more commodious premises in Great Russell Street, close to the British Museum.

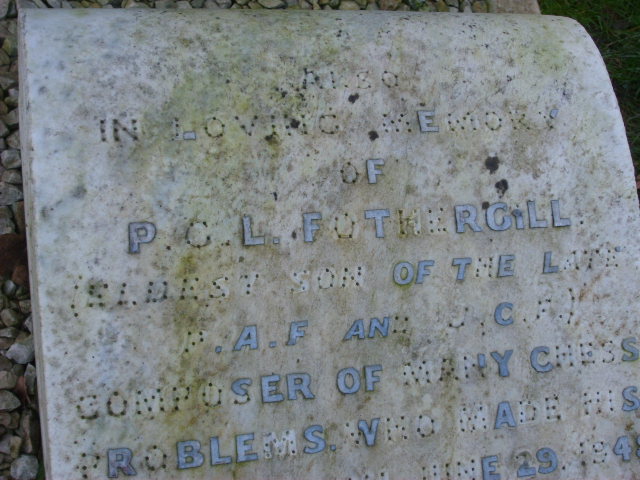

Lady Thomas was the mother of the future Sir George Thomas, and herself a strong player. Alice had been relegated from top board to board 9 by now, partly because of an influx of strong new members. The four players on the middle boards, all, coincidentally, with surnames beginning with F, would go on to play important roles in the Ladies’ Chess Club over the next few years. For the remarkable Louisa Matilda Fagan, I’ll refer you to Martin Smith’s articles referenced below. I hope to write about Gertrude Alison Beatrice Field, Rita Fox and Kate Belinda Finn at some point in the future.

Within a few months they were up to 100 members. Pillsbury visited again and Lasker looked in whenever he was in town.

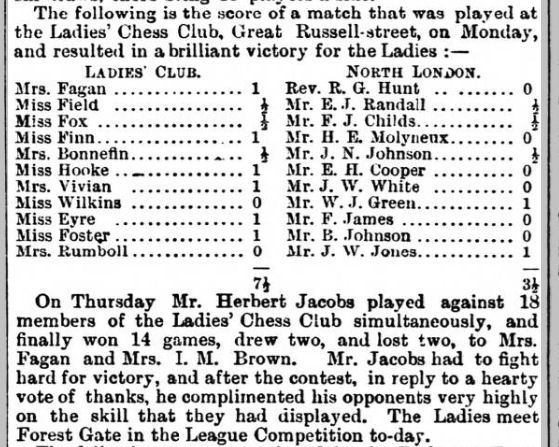

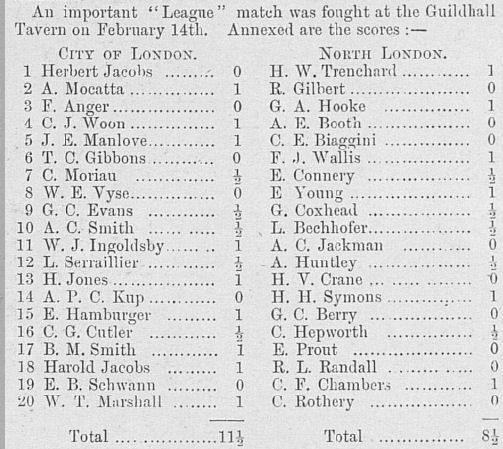

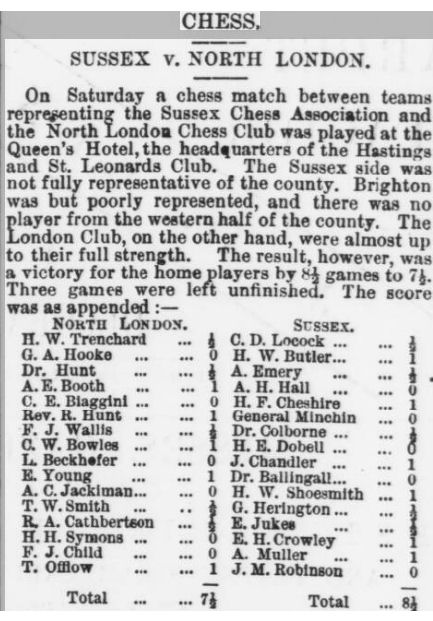

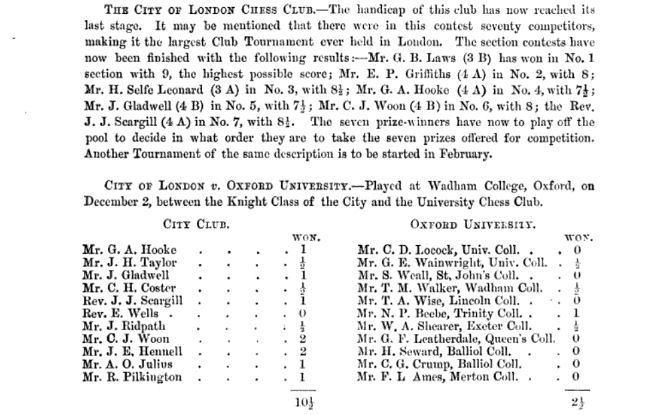

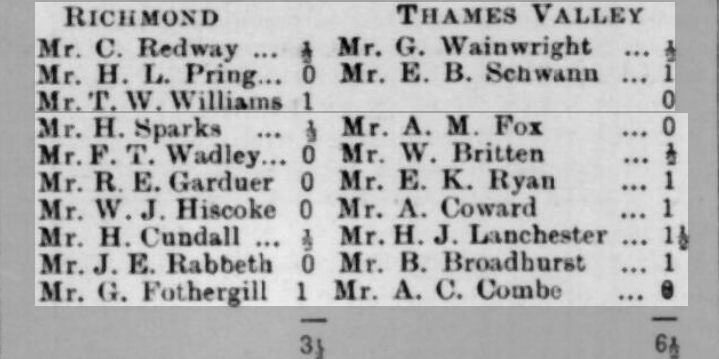

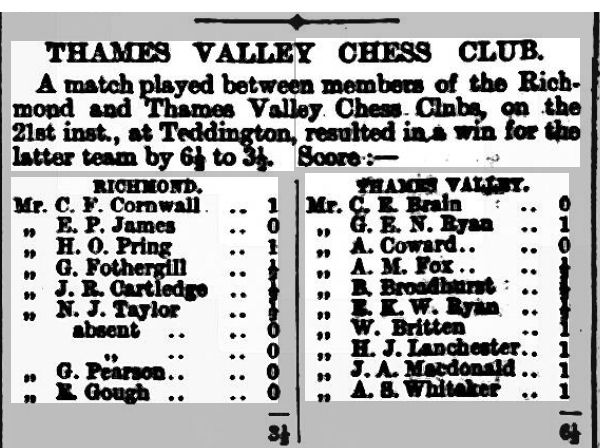

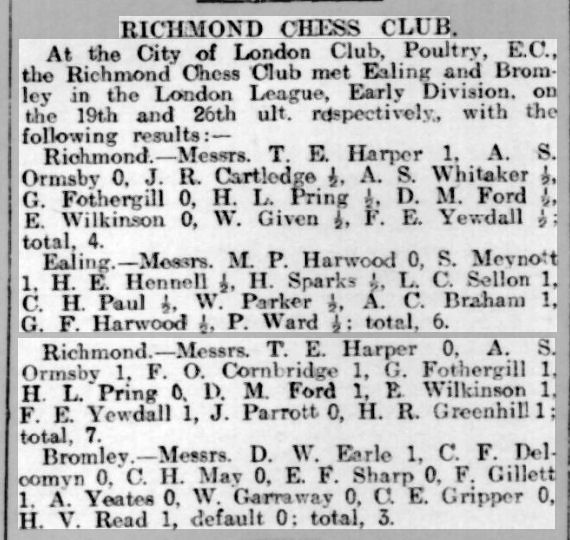

In 1896 the Ladies’ Chess Club entered the London League as well as continuing their programme of internal competitions, friendly matches, such as the one below, against other clubs and simuls, in this case by Herbert Levi Jacobs.

Here, you see the F-squad in place on the top four boards, with the Belgian Marie Bonnefin on board 5 and Alice on board 6. By now they seem to have established their correct board order. While, for many of their members, the club probably served a social function, their strongest players were intensely competitive.

They had even bigger plans in store for 1897 when, to mark Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, they planned to hold an International Ladies’ Chess Tournament at the Hotel Cecil in London.

The strongest lady players from around the world were invited, and, naturally enough, these included several of their club members. Alice Elizabeth Hooke was originally a reserve, but when one of the American invitees withdrew, she was granted a place in the competition.

I’ll refer you to two excellent articles (links at the foot of this post) which provide much more information. The tournament, just like the club, predictably attracted a lot of interest in the press and several of the games were published. Alice’s score of 10 points (8 wins over the board, 2 by default and 9 losses) was more than respectable for a reserve.

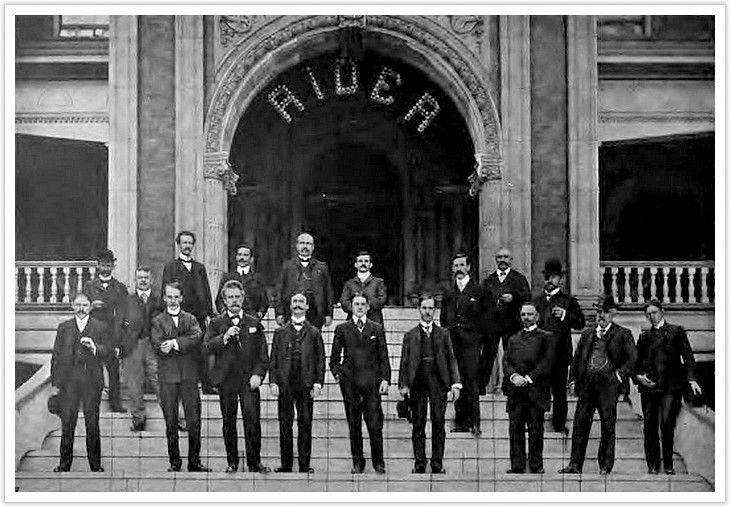

Here’s a photograph of the competitors. Alice, wearing a hat, is standing right at the back against the screen.

In this game against one of the German representatives (her first name is not known, at least to me, but she may well have been related to the organist and composer Carl Müller-Hartung (1834-1908)), her opponent failed to take advantage of an oversight at move 15, after which a poor choice at move 18 allowed Alice to demonstrate some impressive attacking skills. Click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up board.

Against her Belgian clubmate Marie Bonnefin, Alice lost a vital central pawn, after which her opponent’s passed pawns enabled her to bring the game to a neat conclusion.

Alice’s game against one of the F-squad, Gertrude Field, had an interesting finish. Gertrude played an enterprising and correct piece sacrifice on move 25, but missed the immediate Nf3 on move 27. Defending in chess is always difficult, and Alice could have stayed in the game by playing 28… Ne7.

Her best result came in round 8, with a win against Louisa Fagan, who eventually finished in second place. Only a short extract is available, but the opening must have been a Centre Game (1. e4 e5 2. d4 exd4 3. Qxd4), a favourite of both Alice and her brother George. It’s interesting to note that the two siblings frequently played the same rather unusual openings.

Finally, we have a quick win against Miss Eschwege, who, overlooking that her d-pawn was pinned, blundered a piece and immediately resigned. It’s frustrating that, for many years, the press didn’t see fit to use initials for women. Here, again, we don’t know Alice’s opponent’s first name. Her chess playing father, Hermann, was born in Germany, but lived in London. He had three daughters: Kathleen had married by 1897, but either Ida or Nina would be possible. If you know, do get in touch.

The experience of intensive competitive chess, with two games a day over ten days, must have been an educational experience for Alice and the other lady chess players.

Here’s a game she played the following year, where she crowns a strong attack (she did seem to like castling queenside) with a brilliant rook sacrifice.

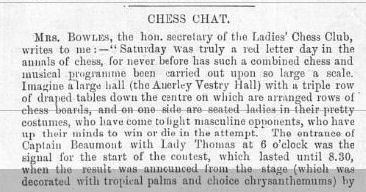

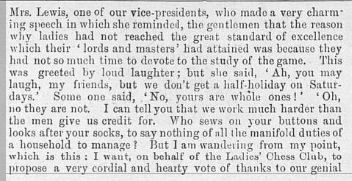

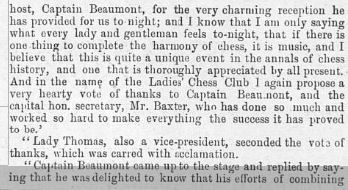

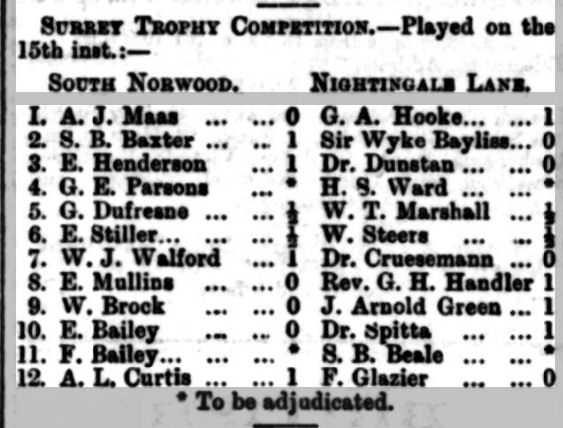

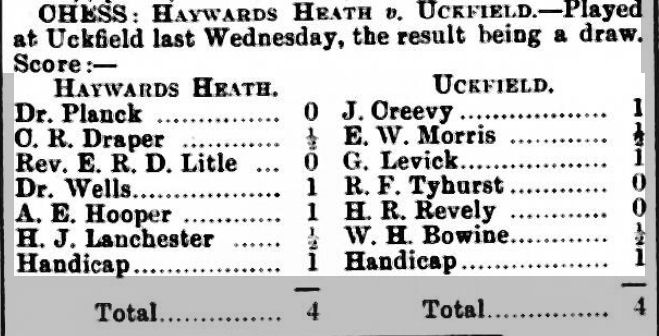

Later that year the Ladies’ Chess Club visited Anerley, near Crystal Palace in South East London, for a combined chess and musical programme.

Captain Alexander Beaumont’s name lives on in the Beaumont Cup, which has, since 1895-96, been the name of the second division of the Surrey Chess League. Frank Gustavus Naumann would later become the first President of the British Chess Federation before losing his life on the Lusitania. Mrs Anderson, on Board 3 for the ladies, was the former Gertrude Alison Beatrice Field, who had just married Donald Loveridge Anderson.

In January 1899 their 4th birthday party’s guests included Lasker, Gunsberg, and, appropriately enough, Antony Guest. As the 20th century approached there was no stopping the Ladies’ programme of matches and social events.

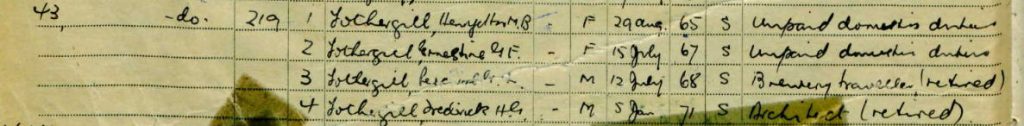

At this time we can find Alice in the 1901 census, living at 27 Croxted Road, Herne Hill with her widowed mother Harriett, and working as a clerk in the General Post Office. This was just 2.3 miles up the A2199 from Anerley Village Hall, and close to Dulwich College School.

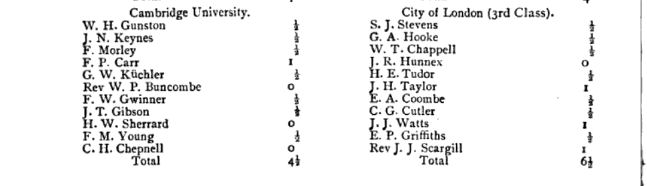

At Whitsun that year Alice, along with her clubmates Louisa Matilda Fagan, Kate Finn and Rita Fox, took part in the open section of the Kent County Chess Association Tournament. I haven’t been able to find the full results, but Miss Finn did well to finish in second place.

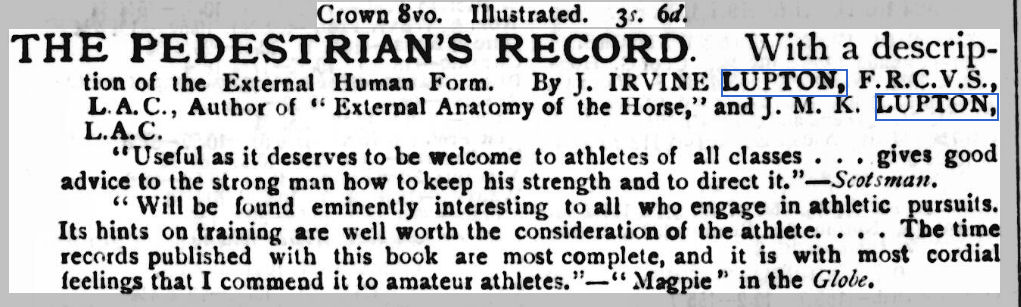

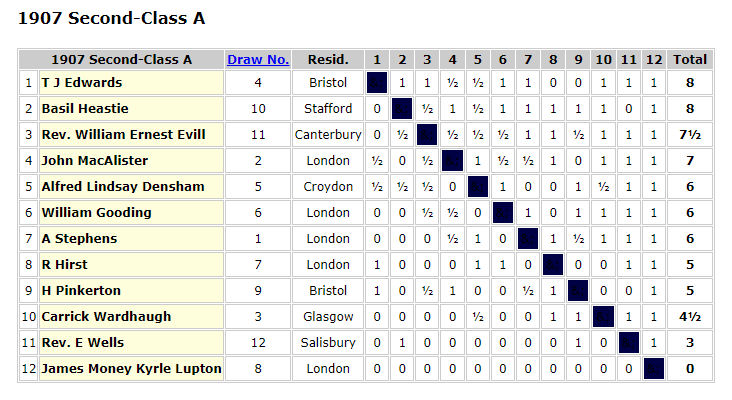

In 1902 she visited Norwich for the British Amateur Championship, playing in the 3rd Class section along with the Misses Foster and Oakley from the Ladies’ Chess Club (and my favourite chess playing clergyman, Rev W E Evill). Miss Finn, Mrs Anderson and a new member of the Ladies’ Chess Club, Mrs Frances Dunn Herring (née Gwilliam) took part in the 2nd Class section.

In 1903 Alice played in the Kent congress in Canterbury, playing in Section A of the ‘Extra’ (2nd Class) section and sharing 2nd place with a score of 4½/7.

The British Chess Championships took place for the first time in 1904, and from the start, the top places in the British Ladies’ Championship were usually taken by members of the Ladies’ Chess Club. Alice Elizabeth Hooke took part for the first time in Shrewsbury in 1906, winning five games and losing six.

In this game against Scotland’s Agnes Margaret Crum, she lost quickly using the Dutch Defence, an opening also favoured by her brother George.

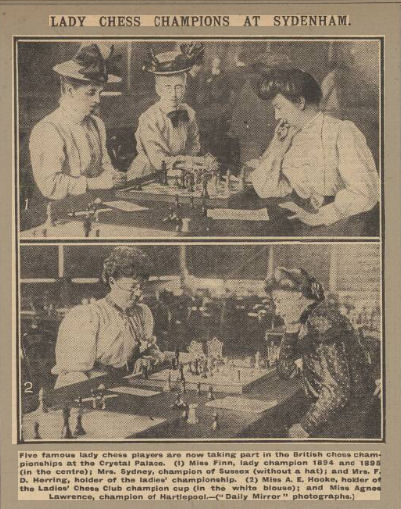

She was back again in Crystal Palace (she wouldn’t have had far to travel) the following year, with a similar result: four wins, one draw and six losses. She was, at this point, and by now in her mid 40s, some way below the best lady players in the country.

Here she is, pictured in the Daily Mirror, on the left in the lower photograph. Her opponent ‘s name was Agnes Lawson, not Lawrence.

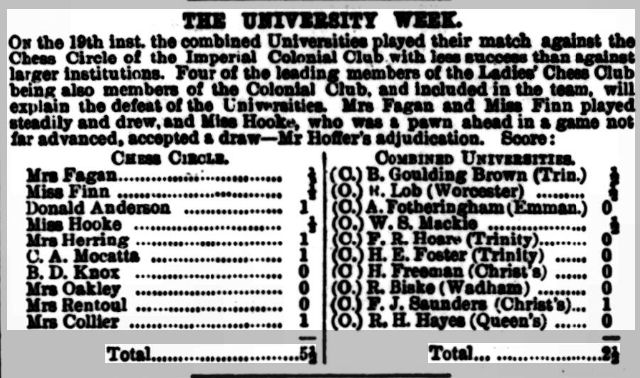

By 1909, Alice had joined a new club, the Imperial Colonial Club, whose chess players seemed mostly to be connected with the Ladies’ Chess Club. There will be a lot more to say about this club in future Minor Pieces.

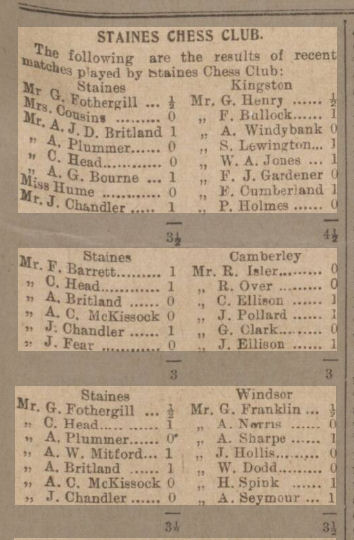

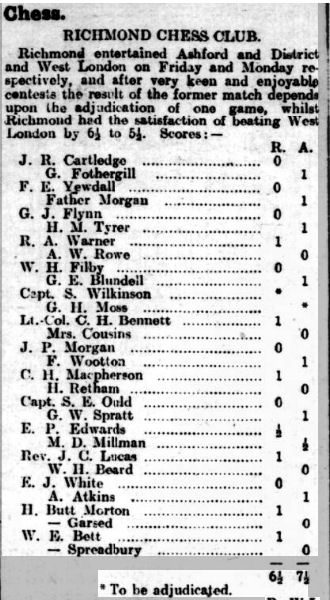

I’m not sure why boards 7 and 8 were reported as a loss for both players.

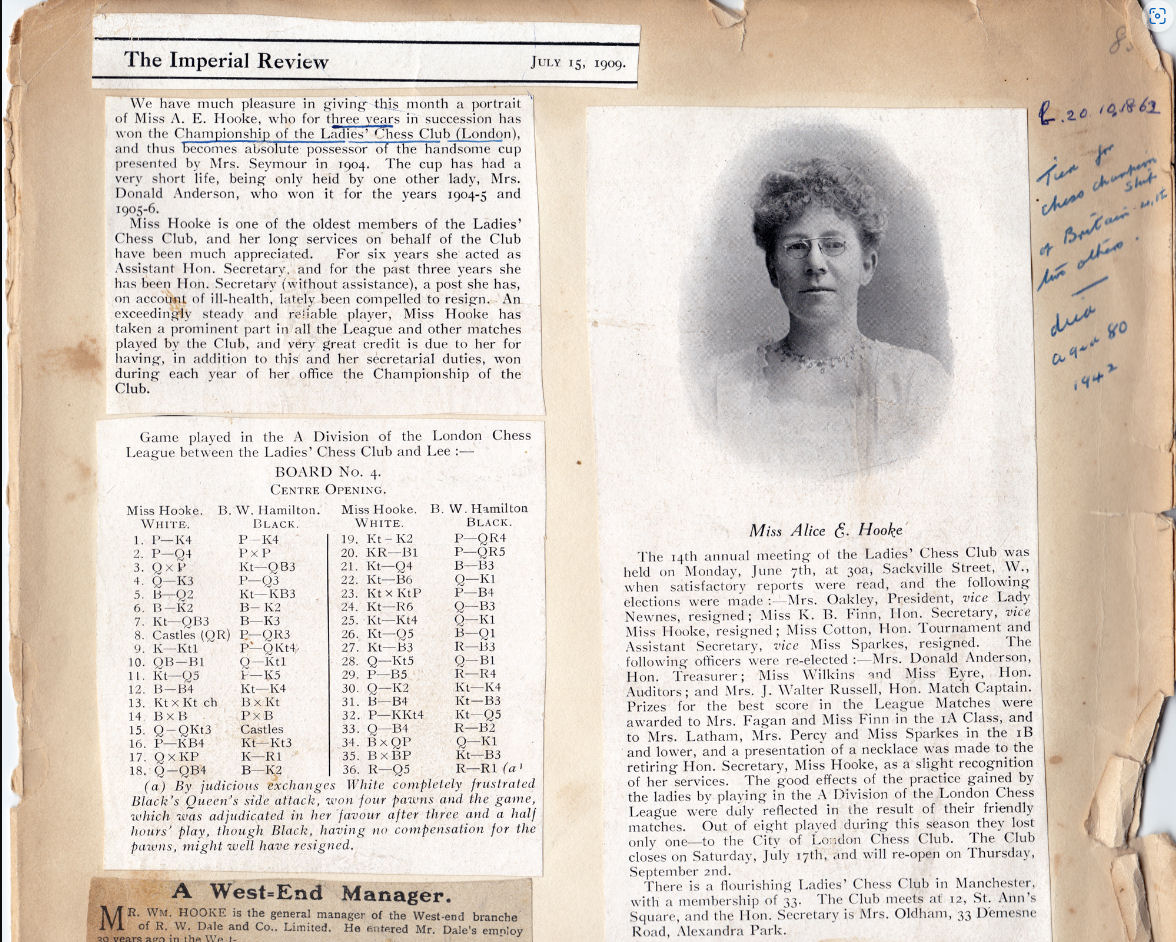

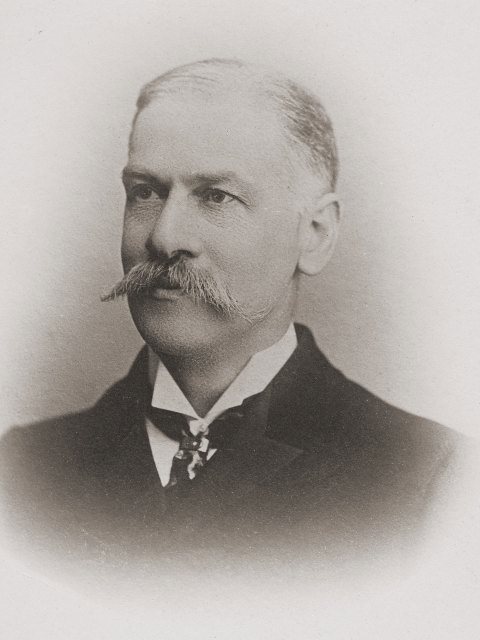

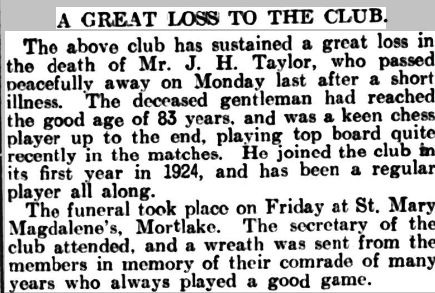

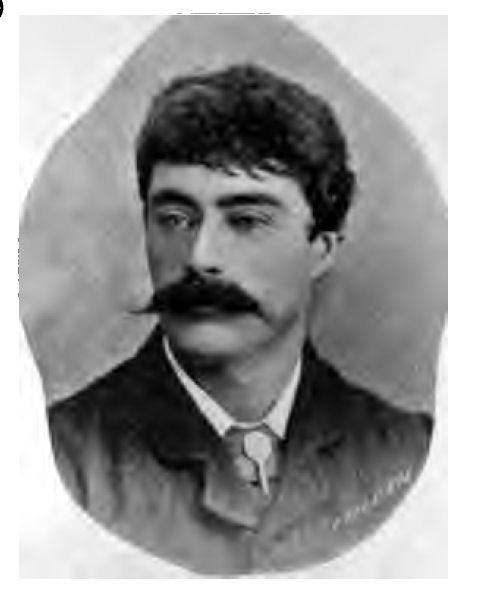

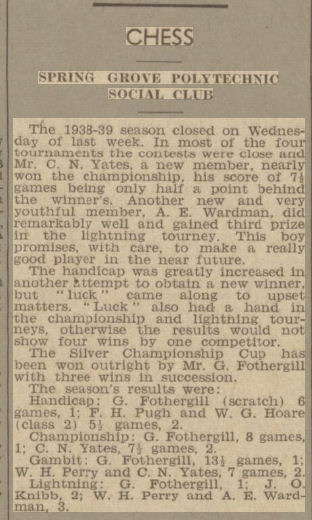

In July, the Imperial Review (perhaps connected with the Imperial and Colonial Club) published a feature on Alice Elizabeth Hooke, with the information that she’d won the Ladies’ Chess Club for the third year in succession, thus acquiring the cup in perpetuity (I wonder what happened to it) but had had to relinquish her post as secretary for health reasons. We also have a rather fine photograph.

Here’s the game for you to play through: you’ll notice the opening variation is the same as that from Alice’s game against Miss Eschwege from 12 years earlier.

Although the Ladies’ Chess Club was still growing, its activities were receiving less publicity in the press. Perhaps the novelty had worn off. It seems that Alice Hooke was less active at this time, perhaps partly because of ill health, and partly because she was having to care for her increasingly frail elderly mother.

By the 1911 census Harriett and Alice had moved to 12 Eatonville Road, Upper Tooting, just a 12 minute walk from Alice’s brother George’s rather more substantial house in Drakefield Road. Alice was now described as a Clerk in the Civil Service.

Harriett died in December 1912, but it wouldn’t be until 1914 that Alice resumed her chess career.

The British Championships took place in Chester that year, and Alice Elizabeth Hooke was back in the Ladies’ Championship, but without much success, winning four games and losing seven.

One game is available, but it doesn’t show her in a good light. She seemed unfamiliar with her opponent’s sharp opening variation, and, after only six moves, had a very bad position. Mrs Holloway was able to offer a bishop sacrifice for a swift victory.

By now she had moved out of London, to Cobham, near Esher in Surrey. Electoral rolls give her address as White Lodge, Cobham. There are two houses of that name in Cobham, about a mile apart. I’d guess it was more likely to be this one than this one. As it was just her and a servant, the smaller and more centrally located property would have been more than adequate. Neither was close to the station, so I wonder how she travelled to work. Jumping ahead for the moment, she was still there in 1921, working as a civil servant in the Post Office Savings Bank in West Kensington.

But then, of course, World War 1 broke out, and, like many others, the Ladies’ Chess Club decided to close its doors for the duration.

As you probably already know from her brother George’s story, this was not the end of Alice Elizabeth Hooke’s chess career. You’ll find out what happened subsequently in the next Minor Piece.

But meanwhile, if you’re interested, there’s a lot more reading material for you.

There’s a lot of information about the Ladies’ Chess Club and the 1897 tournament available in various online sources.

The excellent Batgirl (Sarah Beth Cohen) has written a number of articles on the Ladies’ Chess Club on chess.com.

The Ladies’ Chess Club: The First Year

The Ladies’ Chess Club: Early Years

The Ladies’ Chess Club: Middle Years

See here for a full list of her articles on women’s chess.

My good friend Martin Smith has written a wonderful series of articles about Louisa Matilda Fagan. You can read the first of the series here: there are links to the subsequent articles at the end.

There’s a well-researched article by Joost van Winsen concerning the 1897 Ladies’ Chess Tournament on the Chess Archaeology website here.

Another informative article on the same event by Tim Harding can be found on the Chess Café website here.

Sources and acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

chessgames.com: Alice’s page here.

Britbase (John Saunders): British Championship links here.

EdoChess (Rod Edwards): Alice’s page here.

chess.com

Justin Horton’s blog (no longer active)

Chess Archaeology

Google Maps

ChessBase/MegaBase 2022/Stockfish 15

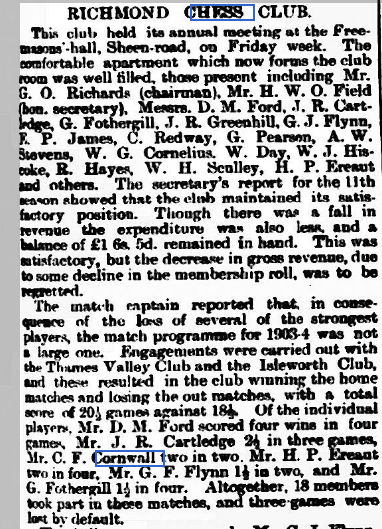

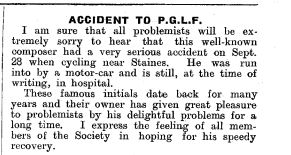

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.