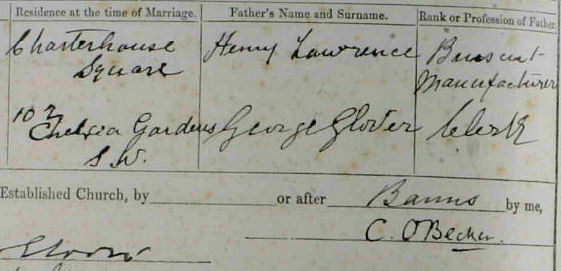

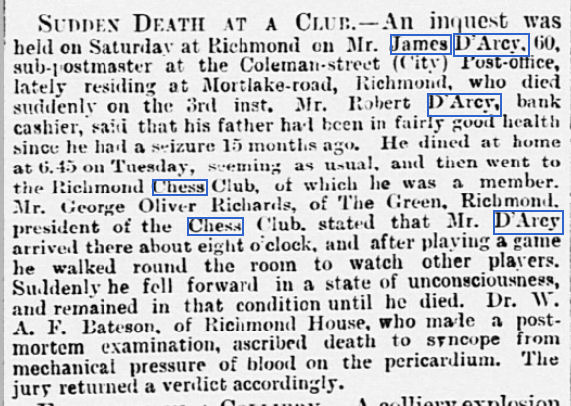

I received some exciting news last week. The Richmond Herald up to 1950, with extensive local chess coverage, is now available online. This means that I’ll be able to trace the history of chess in Richmond, Barnes, Kew and Sheen up to that date, which is not all that long before I came in.

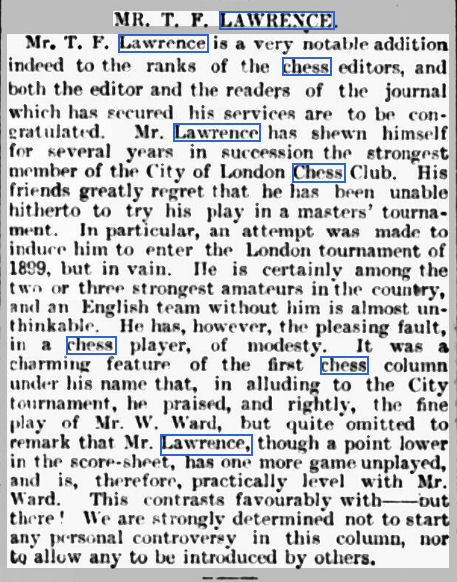

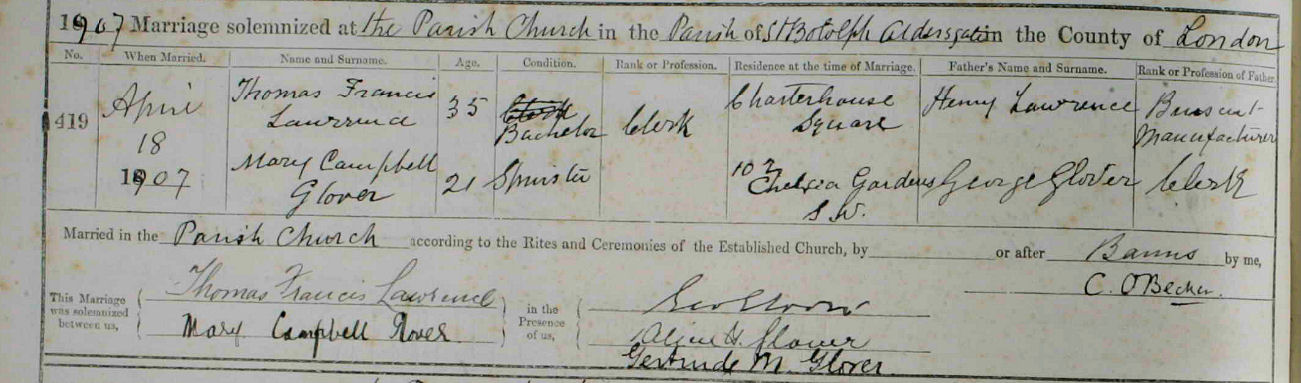

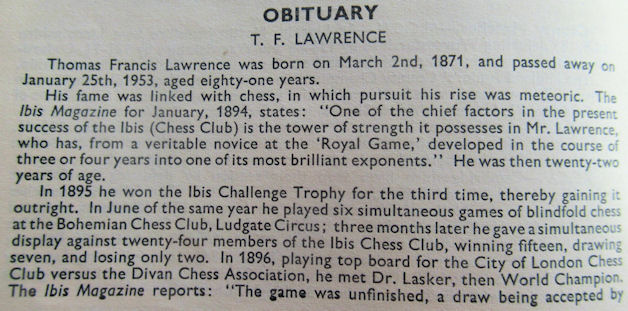

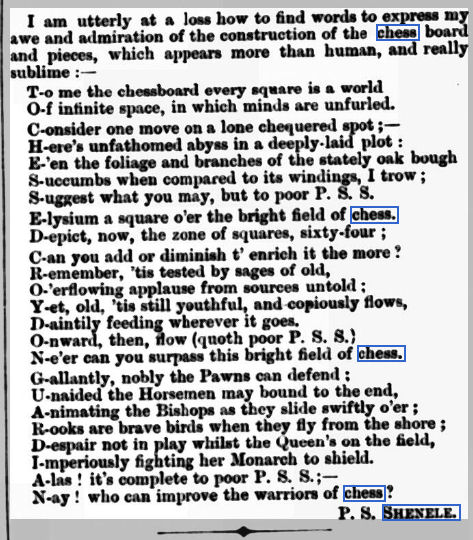

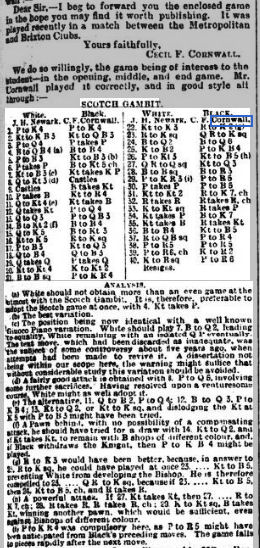

But first, and with some help from the above source, a man who was strangely coy about his rather splendid full name.

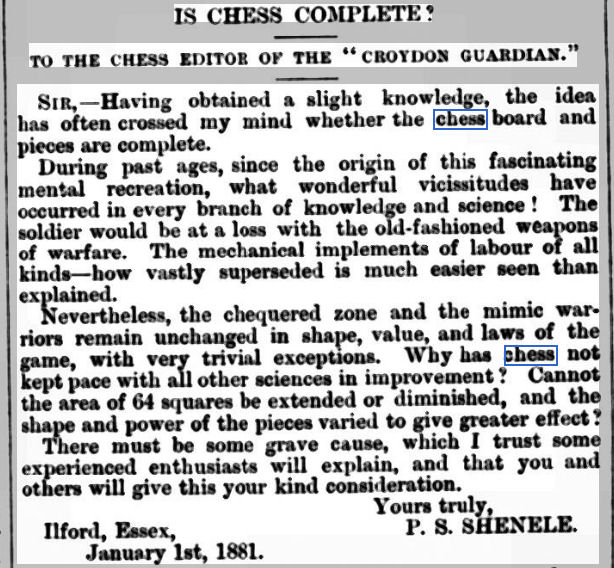

Any chess problem aficionados at any point from the late 1880s to the late 1940s, which, you might think was the golden age of chess problems, would have been familiar with the initials PGLF above compositions, with a location of, perhaps, Twickenham, Staines or Isleworth.

The name G Fothergill was often seen in connection with Richmond Chess Club, and with other clubs in the area. If you’ve been paying attention recently, you might remember him losing in a simul given by TF Lawrence.

In fact he was plain Guy Fothergill on electoral rolls for many years.

A good place to start is with his father, Percival Alfred Fothergill. Percy senior was an interesting and versatile chap. Naval officer, instructor, surveyor, engineer, inventor, astronomer, author, clergyman. You name it, he did it.

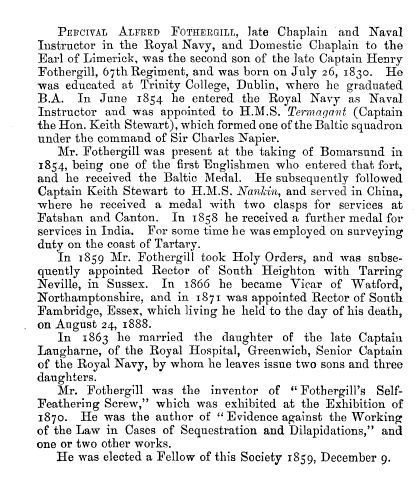

Here’s his obituary, from the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 049:4 (1889).

You might, understandably, be concerned about the self-feathering screw. Don’t worry: it was a propeller for sailing vessels. If you’re really interested in that sort of thing there’s a blog post here.

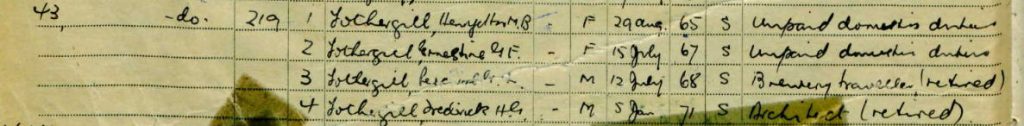

Percival and his wife Julia’s children, all equally impressively named, were Henryetta Mary Bertha (1865), Ernestine Gertrude Frances (1867), Percival Guy Laugharne (12 July 1868), Cornelia Julia Evelyn (1869), Frederick Henry Gaston (1871) and Arthur Yorke Marsh (1872), who died at the age of only six months. Frederick’s baptism record reorders his names: Gaston Frederick Henry.

The only births which were registered appear to be Henryetta and Frederick: at the time the family were moving round the country a lot and perhaps never got round to it.

At the time of the 1871 census Percival Alfred was the Vicar of Watford, Northamptonshire, north east of Daventry. You’ll know it from the Watford Gap service station on the M1. Their five young children, baby Fred yet to be named, were there along with a nurse and two domestic servants.

Ten years later, and the family seem to have split up. Percival was now the Rector of South Fambridge, Essex, on the River Crouch north of Southend, living in ‘part of the rectory’ along with Henryetta and Percival Junior. Julia and the other three surviving children were 20 miles away in Orsett, near Grays, on the Thames Estuary. One wonders what had happened.

There’s no immediate evidence of any other serious interest in chess in the family, but it was from his father that young Percival (perhaps we should call him by his preferred name, Guy, or by his initials) first discovered the Royal Game. By 1886 the teenage Fothergill was already having his problems published.

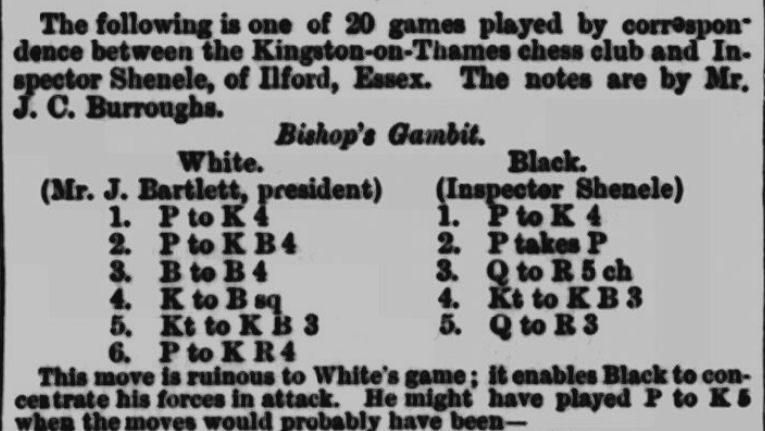

Here’s a (rather crude) early example of a mate in 2. You’ll find the solutions to all the problems at the end of the article.

Problem 1

#2 (The Field 11 Sep 1886)

His problems were soon becoming more sophisticated and even winning prizes, like this mate in 3.

Problem 2

#3 (2nd Prize Sheffield Independent 1888)

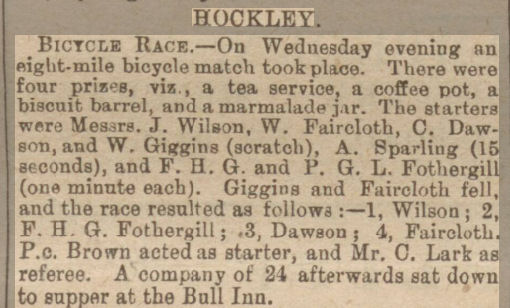

Problem composing wasn’t the only competition he took part in. Here, he and his brother took part in a bicycle race, with Fred winning a coffee pot for finishing second.

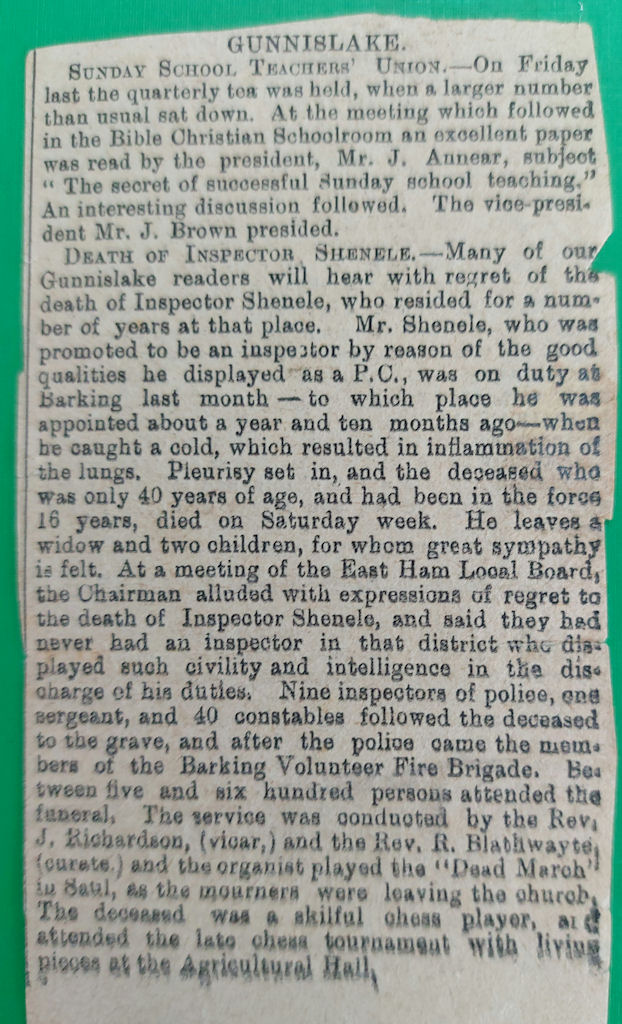

Sadly, his father died the same year in Little Burstead, south of Billaricy, the village where he was born. By the time of the 1891 census he’d left home, was boarding in (not yet Royal) Wootton Bassett and working as a Brewer’s Pupil. Julia had retired to Milford, on the Hampshire coast, where she was living with Henryetta, Cordelia and Gaston, as Frederick now preferred to me known. Ernestine was in Acton, working as a Governess.

PGLF won 1st prize with this 1894 mate in 2.

Problem 3

#2 (1st Prize Hackney Mercury 1894)

Round about 1895 the family moved to St Margarets Road, on the border of Twickenham and Isleworth. I’m not sure exactly where, but the 1901 census implies it was somewhere close to the Ailsa Tavern.

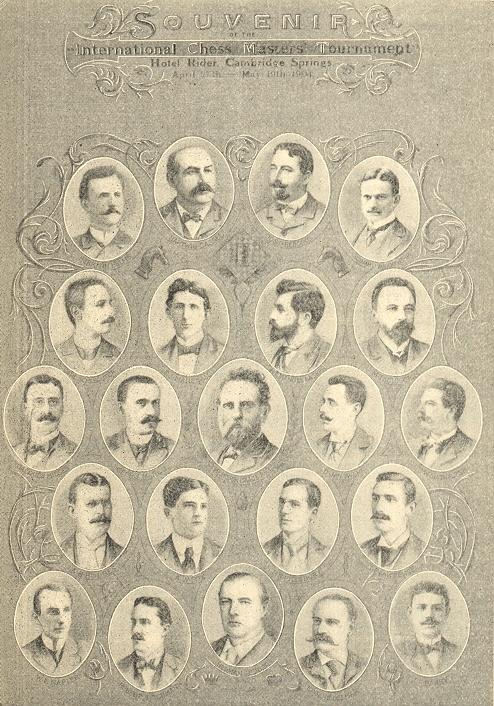

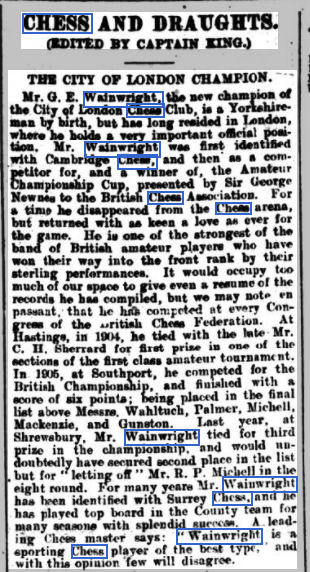

As expected, PGLF featured in FR Gittins’ The Chess Bouquet in 1897.

His list of successes is not large, nor are they phenomenal, but his work has merited and received a fair reward…

We also learn that

MR FOTHERGILL is a great lover of all manly games – cricket, football, lawn tennis, etc., a sound mind in a sound body being one of his favourite maxims.

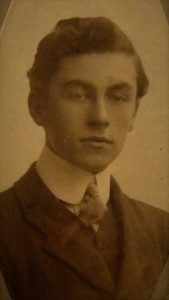

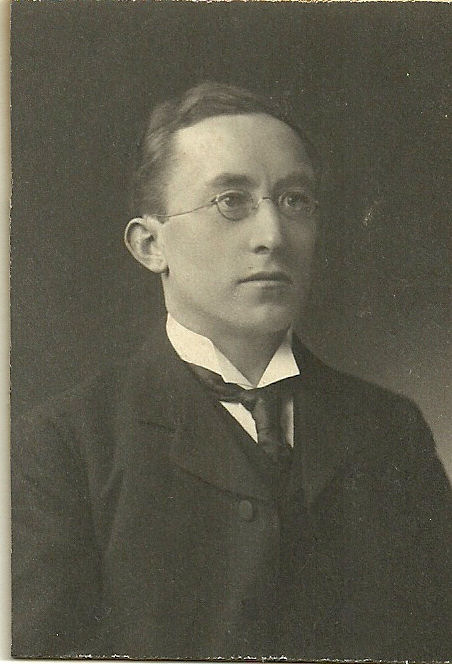

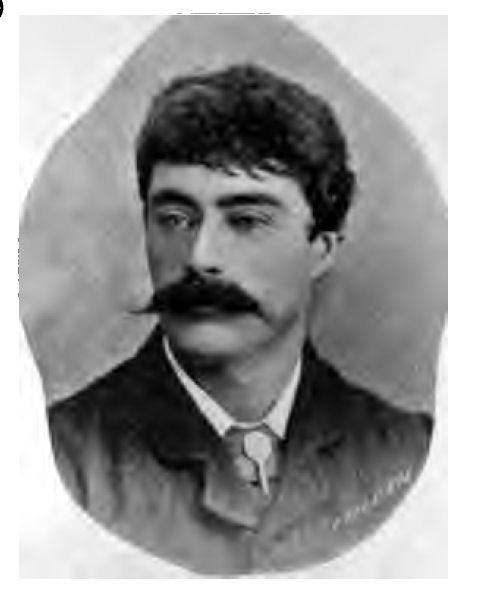

And here he is, with a splendid moustache to match his splendid name.

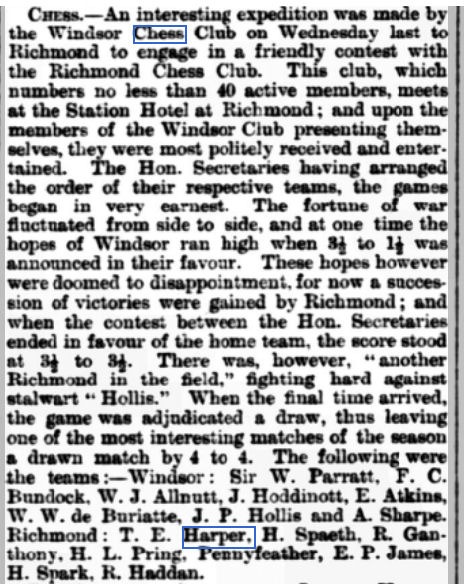

It’s at this time that Guy decided to expand his interest in chess, and, while still composing (as PGLF), his name (G Fothergill) started to appear in chess matches.

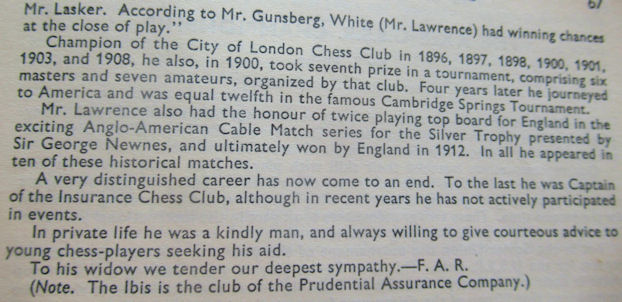

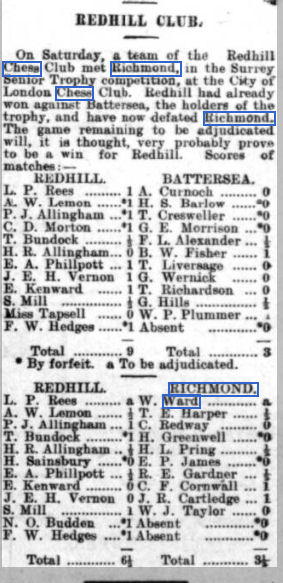

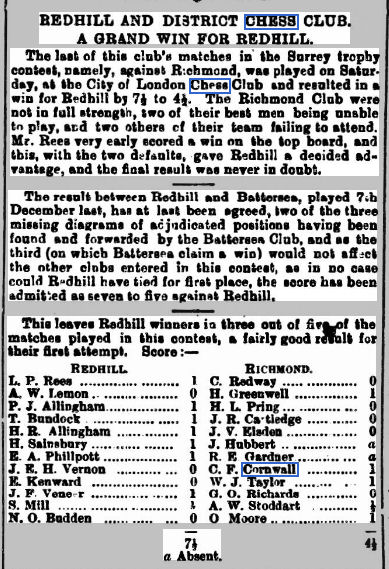

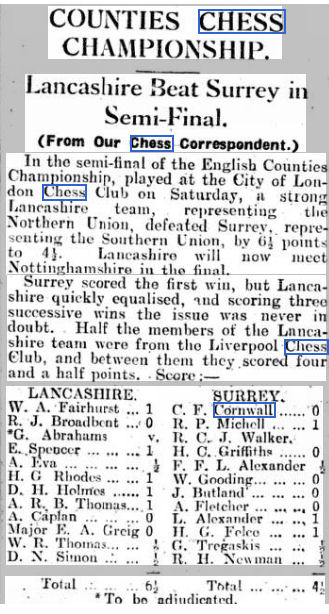

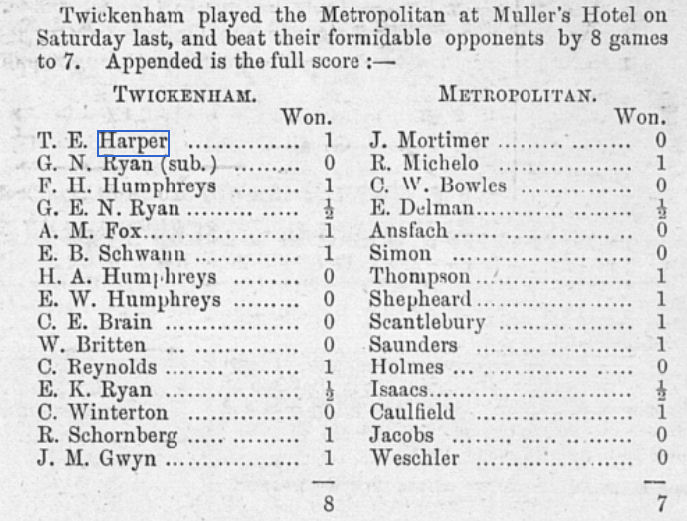

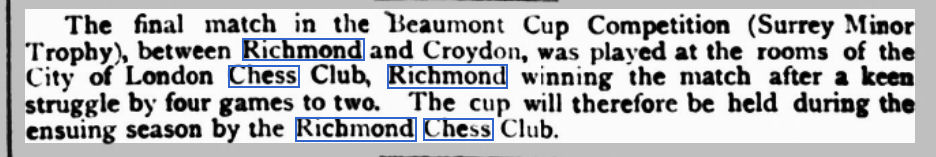

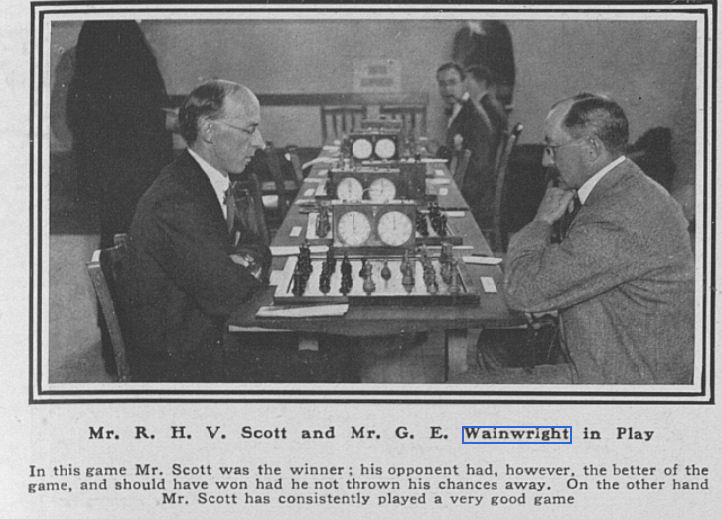

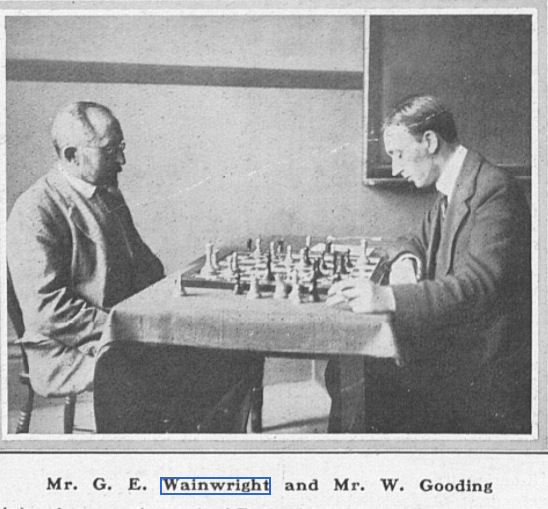

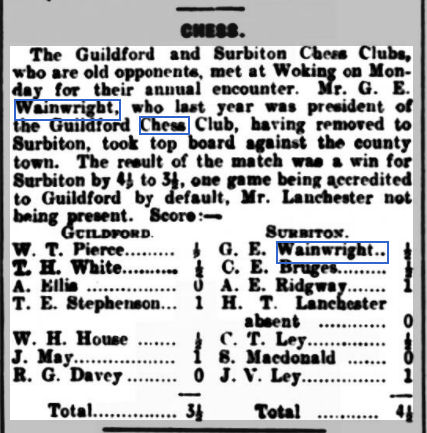

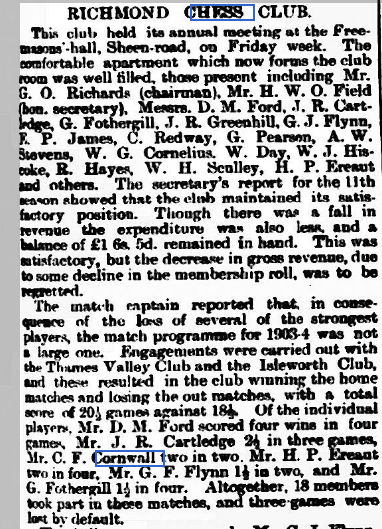

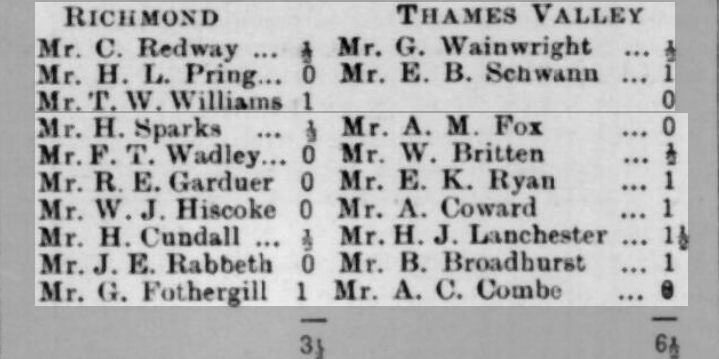

Here’s a 1899 match between Richmond and Thames Valley, with Mr G Fothergill playing on bottom board for the home team.

It’s clear there’s a problem with this. Fox, Britten, Ryan and Coward must have been on 3-6, not 4-7, with Lanchester and another player on 7 and 8. Regular Minor Piece readers will recognise several old friends in this match, and there are one or two others you’ll meet in later articles.

The 1901 census found Julia, Henryetta, Cordelia and Gaston, who was now known as Henry, in residence in St Margarets, none of them appearing to have jobs. Ernestine, however, was occupied as a Lady’s Companion in Hersham. I haven’t managed to locate Guy in 1901: perhaps he was abroad on holiday. At any rate, he was still telling everyone he lived in Twickenham.

From the same year, here’s another prize-winning problem.

Problem 4

#2 (3rd Prize Brighton Society 1901)

This miniature 3-mover demonstrates a popular theme. Even if you’ve never solved a mate in 3 before, give it a try!

Problem 5

#3 (Schachminiaturen 1903)

At about this time Guy Fothergill suffered two bereavements: his mother Julia died in 1905, and his sister Cornelia followed her a year later. Probate records tell us they were both living at Shortwood House, Staines: Shortwood Common is right by the Crooked Billet roundabout heading towards Ashford. Julia’s probate was granted to Henryetta and Guy, and Cornelia’s probate just to Guy. Although she was living in Staines, she died at 89 St Margarets Road, Twickenham. The numbering may be different now, and it’s a long road, but 89, currently a private healthcare clinic, is currently just round the corner from Turner’s House and a short walk from the ETNA Community Centre, where Richmond Junior Club met for many years. So it may well be that the family owned two properties at the time. It’s not at all clear to me at the moment whether or not this is the same address they were at in 1901.

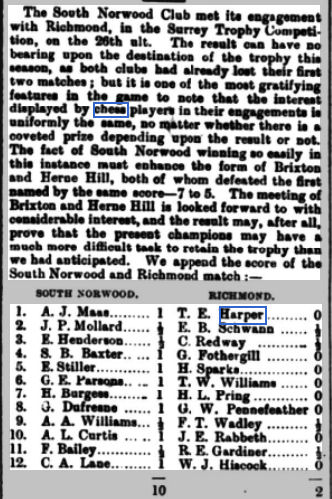

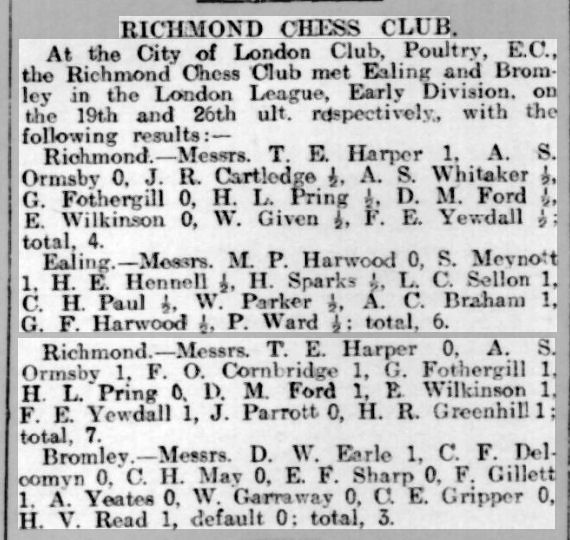

As the Edwardian era wore on, there were subtle changes in the balance of power between the Richmond and Thames Valley Clubs. At the start of the decade Thames Valley had been stronger than their younger neighbours, but a few years later Richmond were displaying more ambition (and, it appears, better organisation than a few years earlier), entering the Early Division of the London League and attracting stronger players. (I presume the Early Division played matches earlier in the evening than, well, perhaps the Late Division?)

You’ll also notice that by now Guy had been promoted from bottom board, and AGM reports for the period show that he was also doing well in internal competitions,

Now approaching his 40th birthday, life for PGLF proceeded uneventfully as he continued to play chess and compose problems.

The 1911 census, though, finds the Fothergill siblings split up, living neither in Staines nor in Twickenham. Guy, ‘of private means’, was boarding at a Temperance Hotel in Maidenhead (what happened to his brewing career, then), while Henryetta and Ernestine were both staying with a restaurant owner in Reading, who may well also have had rooms for boarders. There’s no sign of their younger brother.

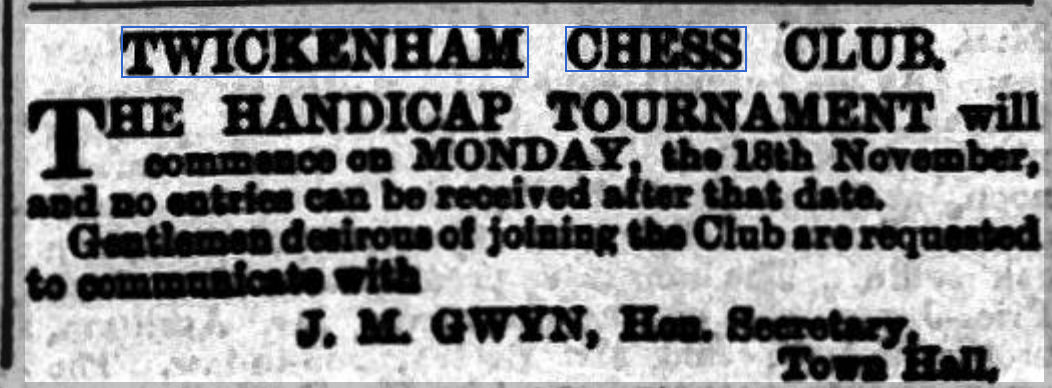

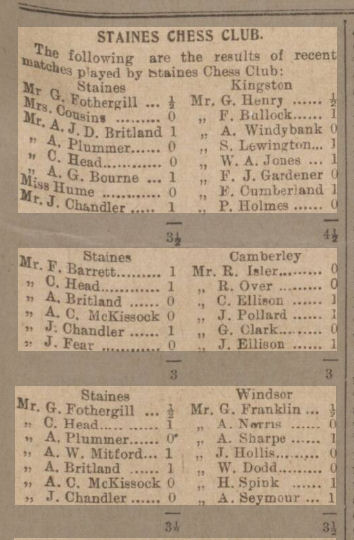

By 1914, PGFL’s problems are now being submitted from Staines. Was he living in Shortwood House? Possibly: at present that information isn’t available. He also had the opportunity to join a new chess club.

You’ll notice that there were two ladies in the team facing Kingston: Mrs Cousins and Miss Hume. We’ll return to them in a future Minor Piece.

He maintained his membership of Richmond Chess Club as well, taking part in internal competitions and serving on the committee.

In 1918 PGLF was enrolled as a founding member of the British Chess Problem Society.

The country was now returning to normal after the First World War, and the 1919 electoral roll tells us that Henryetta was still at Shortwood House, London Road, Staines. By 1921 she’d been joined by ‘Fred’ (neither Gaston nor Henry) and Percival (not Guy).

Neither brother was anywhere to be found in the 1921 census (at least I haven’t been able to find them yet). Their two sisters, both still unmarried in their mid 50s, were lodging in Goldhawk Road, Hammersmith, near the junction with King Street – even though the electoral roll had Henryetta in Staines. The census enumerator found the house unoccupied.

A short walk from Goldhawk Road along King Street towards Hammersmith Broadway would have taken them past Latymer Upper School, and then round the corner to what is now the London Mind Sports Centre.

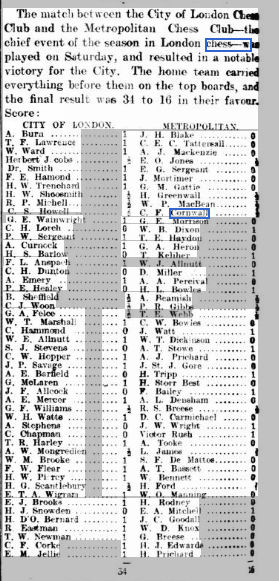

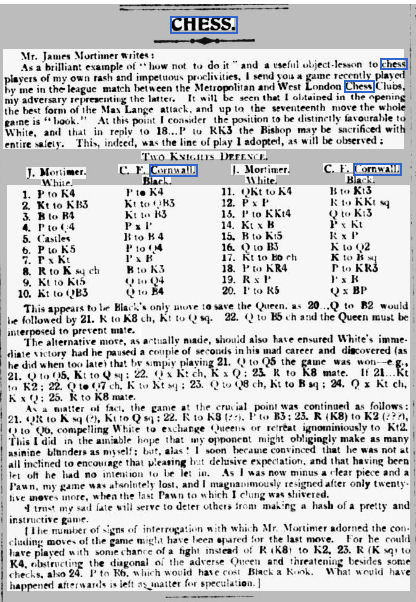

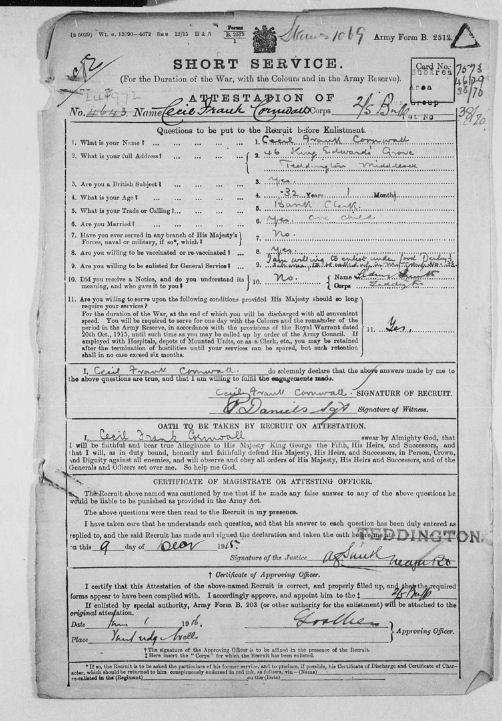

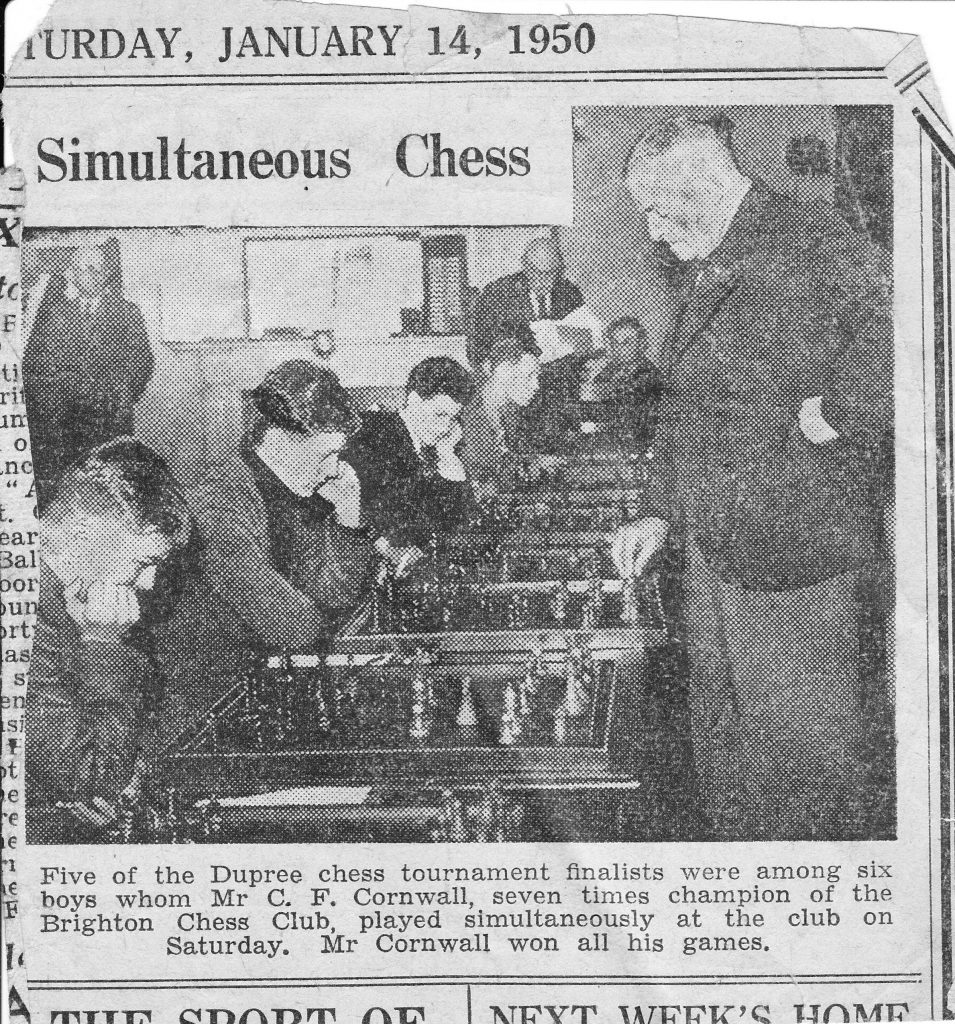

If they’d only stayed in Staines another year or two they could have strolled past the Crooked Billet towards the town centre and dined at 8 London Road, the Warwick Castle, where the Misses Ada and Louisa Padbury were combining running a restaurant with bringing up their irresponsible sister Florence’s illegitimate daughter Betty. But that’s another story for another time, which also involves Edward Guthlac Sergeant and Fothergill’s Richmond teammate Cecil Frank Cornwall.

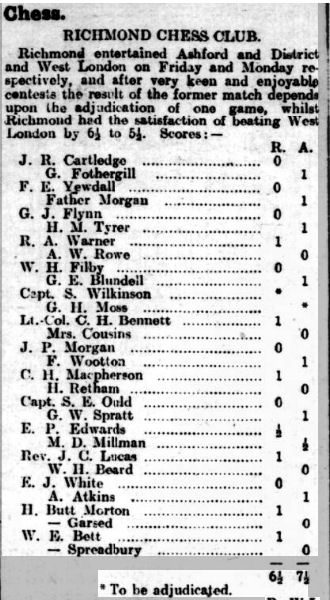

At some point, perhaps just after, WW1, the Ashford and District Chess Club was founded. Guy, along with Mrs Cousins, joined up, he soon found himself playing successfully on top board against Richmond. It may well have been on his initiative that matches between the two clubs came about. Today there’s a Staines Chess Club, but not an Ashford Chess Club.

In 1922 Henryetta must have sold Shortwood House and brought a property in Isleworth, 43 Thornbury Road.

I’m not sure that the house still exists. 41 is a large corner property, but the adjacent plot seems empty according to Google Maps.

She’s the only occupant on the electoral roll for several years, but by 1929, Guy (not Percival this time) is also there, although Henryetta is declared to be the owner. I presume he’d been living there all along, though, as he was giving Isleworth as his residence when submitting problems for publication.

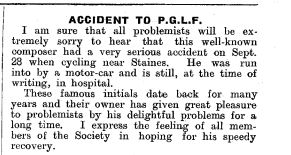

He still visited his old haunts in Staines, but in 1936 was seriously injured in a cycling accident. Fortunately, he made a full recovery.

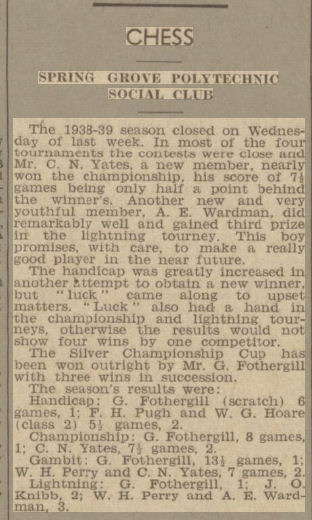

By the late 1930s, if not earlier, he’d found a very local chess club to join, just round the corner from his residence.

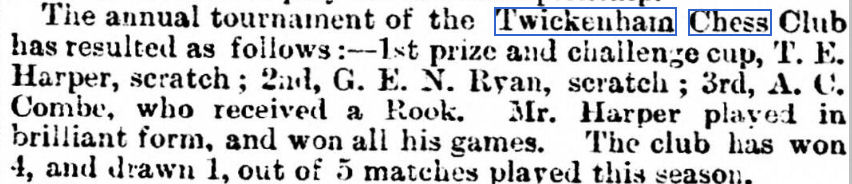

He was now in his seventies, but still made a clean sweep of all the trophies. The opposition may not have been the most demanding, but you can do no more than beat what they put in front of you.

Here they all are in the 1939 Register, all living in Thornbury Avenue (perhaps they’d all been there all along), all single, and aged between 65 and 71. Percival is a Brewery Traveller (retired), but I’m not sure he did much Brewery Travelling, while Frederick is an Architect (retired), but again I’m not sure he designed very many buildings. I can’t find any record of him in that sphere.

PGLF was still composing, though not quite as prolifically as before. This 3-mover from the latter part of his career demonstrates the theme of symmetry.

Problem 6

#3 (The Problemist March 1944)

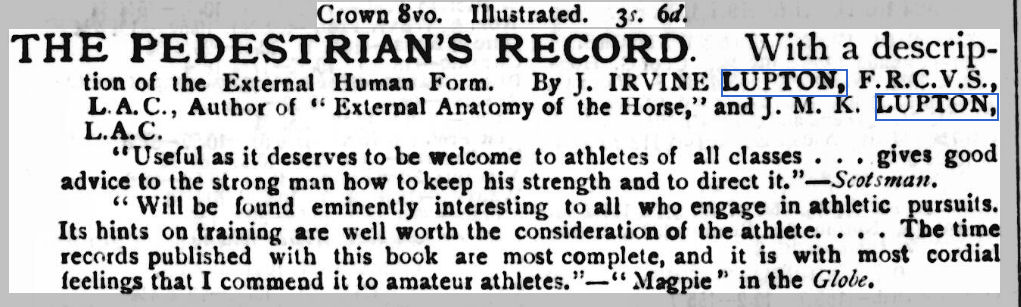

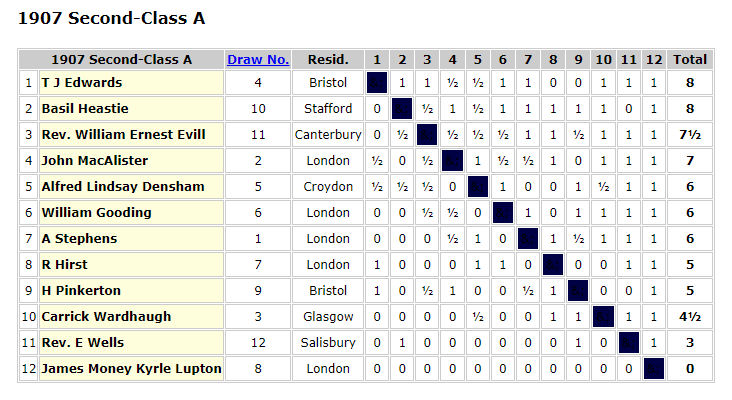

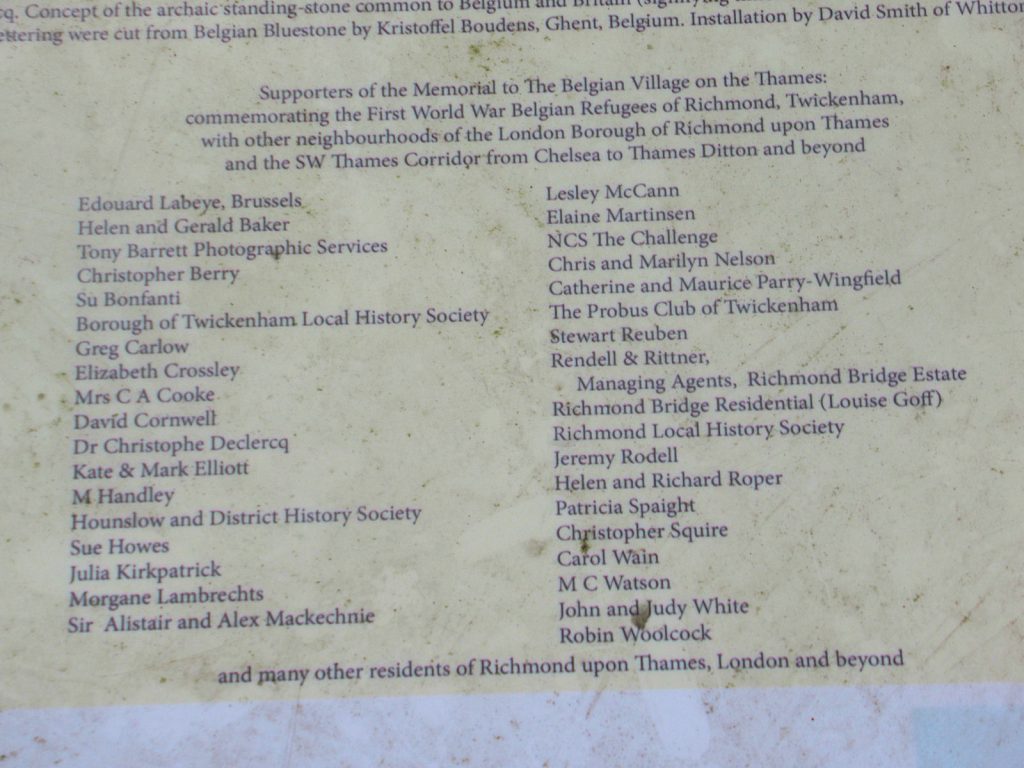

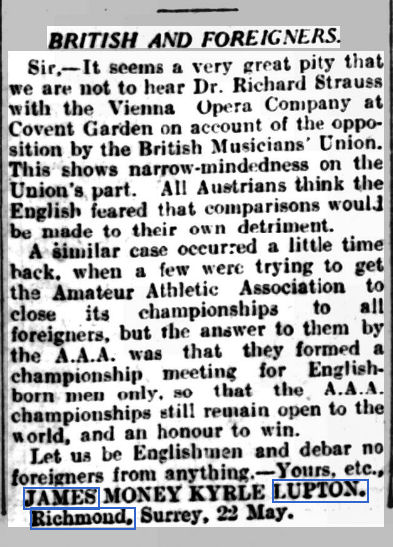

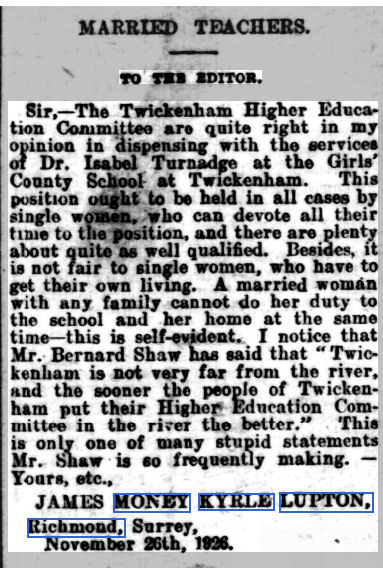

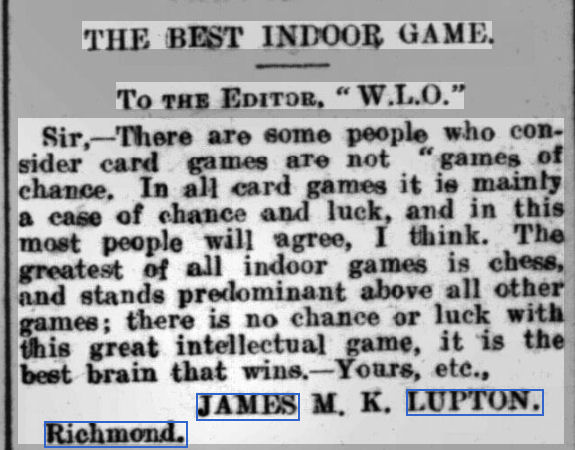

This, then, was a fairly wealthy family, with enough money not to need much in the way of employment, and seemingly with no interest in matrimony. This gave them time to pursue their hobbies, and, in PGLF’s case, that hobby was chess. It’s spookily like James Money Kyrle Lupton‘s family, isn’t it?

Ernestine was the first to go, dying in 1945 and leaving £6711 (round about £200000 to £250000 today), probate being granted to Frederick.

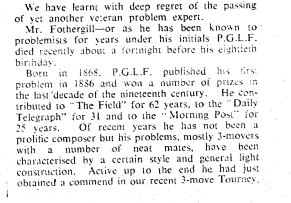

Percival/Guy/PGLF died on 29 June 1948, leaving £4486 10s 4d, again probate being granted to Frederick. He was composing to the end: almost two years after his death, his problems were still being published.

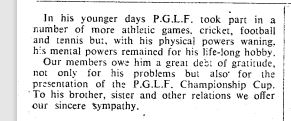

Here’s his obituary from The Problemist, rather belatedly in January 1949.

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

Unfortunately, also, the recent commendation turned out to be cooked, so I won’t demonstrate it here.

Henryetta, address given as 32 Stamford Brook Road, just round the corner from where she was in 1921, died in 1954, leaving £5528 8s 10d, yet again probate granted to Frederick.

Frederick, or Gaston, or Henry, or whatever, lived on until 31 December 1962, living at 45 Woodlands Grove Isleworth, not far from Thornbury Road, and leaving £15307 17s.

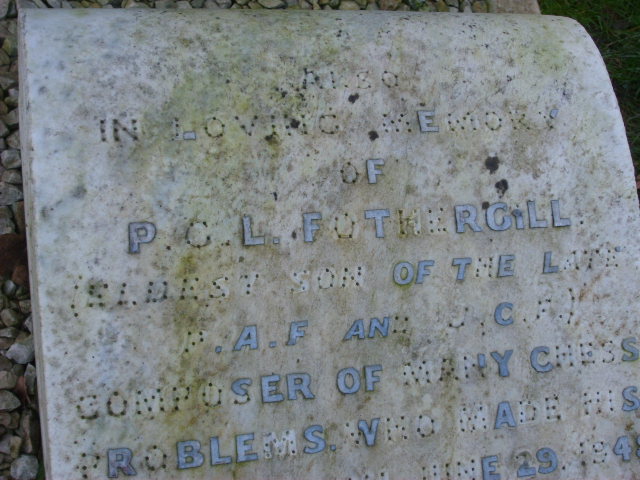

Four of the siblings (not, for some reason, Ernestine) share a gravestone in the family’s home village of Little Burstead, Essex. Percival’s inscription reads:

| Also in loving memory of P.G.L. FOTHERGILL [eldest son of the late P.A.F. and J.C.F.], composer of many chess problems who made his last move on June 29 1948 on the eve of his 80th year.

“Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace whose mind is stayed on Thee because he trusted in Thee.” Isaiah XXVI. 3 |

Yes, indeed, a composer of many chess problems. Mostly direct mates, latterly mostly mates in 3, but with a few selfmates (where White compels an unwilling Black to deliver checkmate). Mostly lightweights rather than heavy award-winners, but none the worse for that. He was, similarly, a good chess player – higher club standard – but not a great one. I have yet to find the scores of any of his games. Percival Guy Laugharne Fothergill was a man who, through his problems, must have brought a lot of pleasure to a lot of people. Perhaps you’ll derive some pleasure from attempting to solve the problems in this article. A minor contributor to a minor art form, I suppose, but still a life well lived and well worth remembering.

If you’d like to see more of his (or anyone else’s) problems I recommend:

https://www.yacpdb.org/

http://www.bstephen.me.uk/meson/meson.pl?opt=top

https://www.theproblemist.org/mags.pl?type=tp

Acknowledgements and sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

findagrave.com

Wikipedia

Google Maps

The Problemist

MESON chess problem database

YACPDB (Yet Another Chess Problem DataBase)

Other sources referenced within the article

Problem solutions.

Problem 1:

1. Qd8! and all four Black moves allow knight mates. There are duals in three of the four variations, which wouldn’t be acceptable today.

Problem 2:

1. Ba3! when the star line is 1… Kxc4 2. Qb5+! Kxb5 3. Nd6#. Also 1… Kxe4 2. Qe2+, 1… Ke6 2. Qb6+, 1… d3 2. Qd5+ and 1… g2 2. Qb5+

Problem 3:

1. Re8! A waiter, very popular at the time. The move creates no threat, but every Black move creates a weakness allowing White to mate next move. You can work them all out for yourself!

Problem 4:

1. Bh2! Another waiter: again there’s no threat but every possible Black reply allows immediate checkmate. There are quite a lot for you to find!

Problem 5:

1. Nc3! Kb4 2. Qc4+!, or 1… Kb6 2. Qe7!, or 1… Kd6 2. Ne4+!, or 1… Kd4 2. Ne4! This demonstrates the Star Flight theme: Black’s four possible king moves, SW, NW, NE and SE, make the shape of a star.

Problem 6:

There’s some set play: if it was Black’s move 1… c2 would be met by 2. Qa5. There are also two tries: 1. Rg7? d5+! and 1. Rc7 f5+!

So the solution is 1. Qe3! when it’s not difficult for you to work out the variations after Black’s four possible replies.