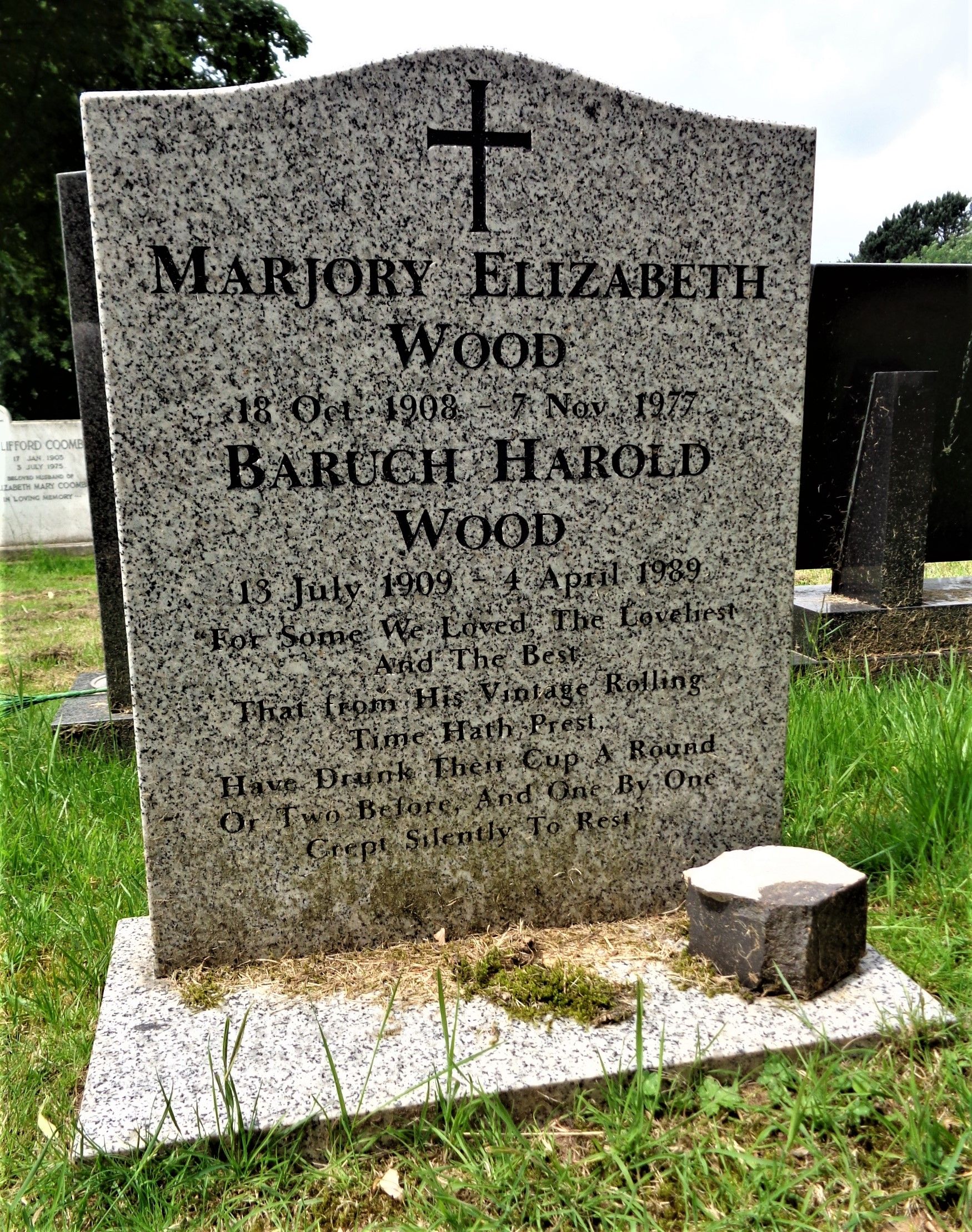

We remember “BH” Wood MSc FCS OBE who passed away on Tuesday April 4th, 1989 in the district of Birmingham.

He was buried alongside his wife Marjorie in the Sutton Coldfield Cemetery Extension which was opened in 1934 as an extension to the Holy Trinity Church.

Yorkshire Childhood

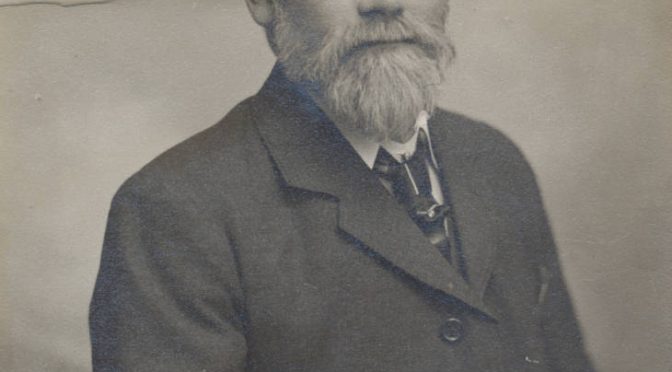

Baruch Harold Wood (generally known as BH Wood, or simply “BH”, by the chess world) was born on Tuesday, July 13th 1909 in Ecclesall, Sheffield, Yorkshire. The registration district was Ecclesall Bierlow.

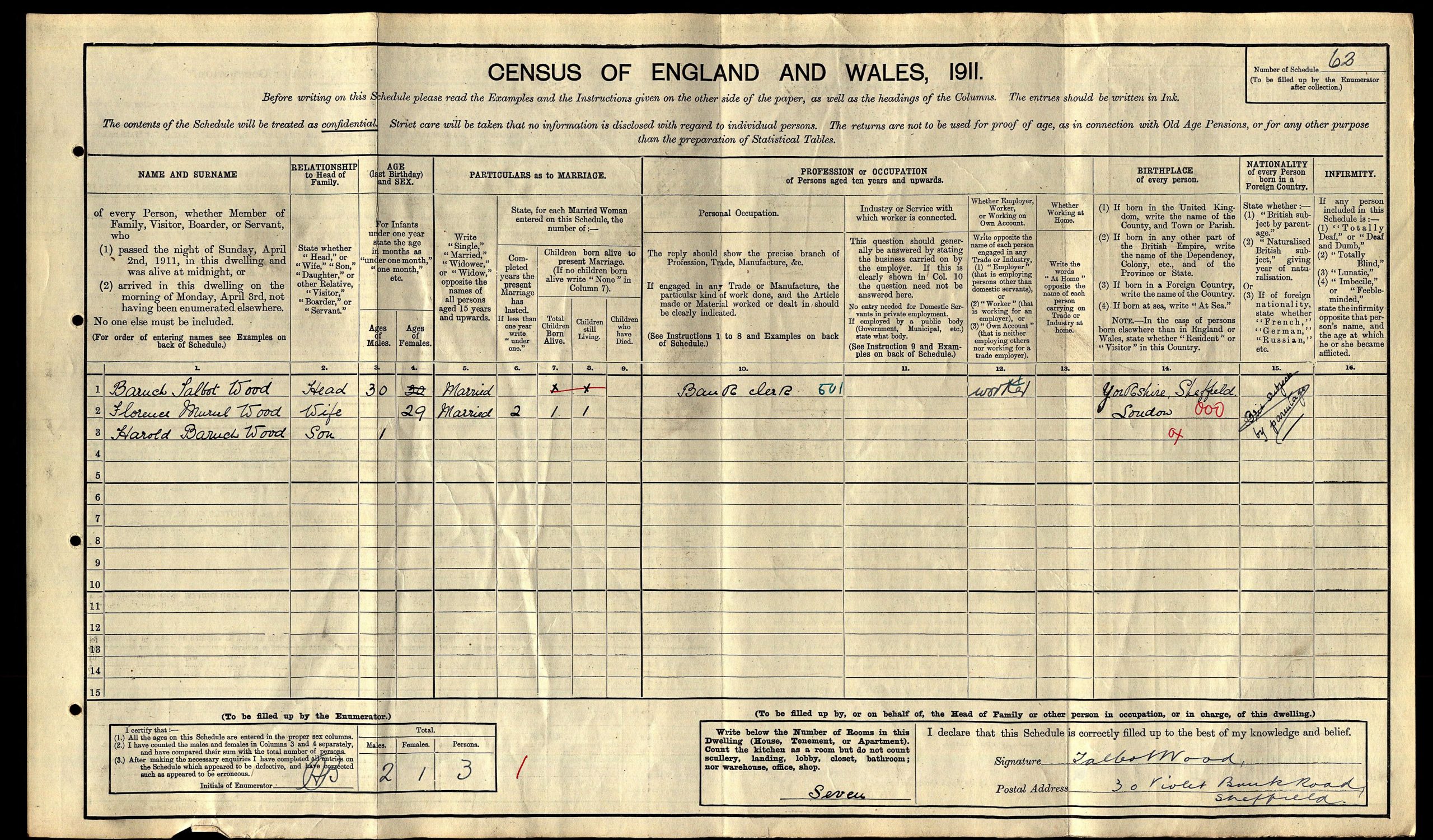

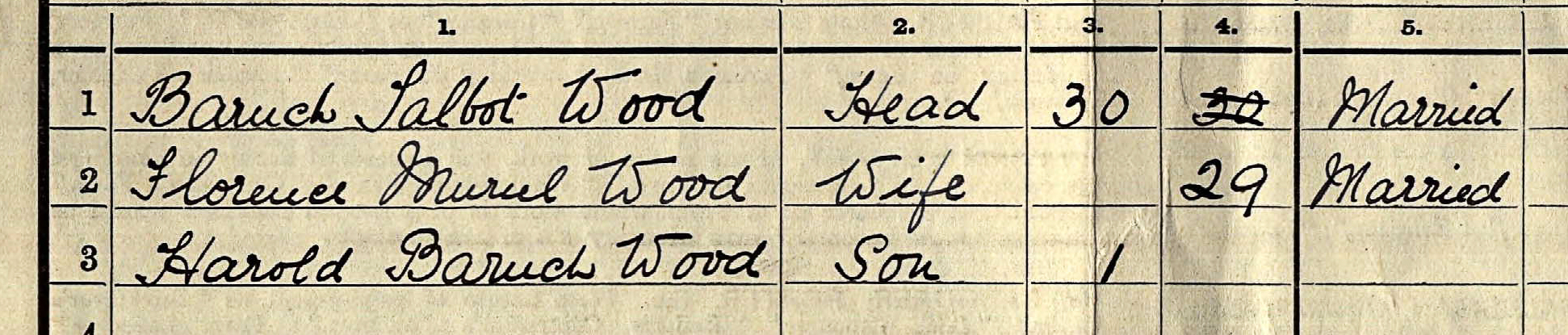

The birth record suggests that he was baptised as Harold Baruch Wood. His parent’s were Baruch Talbot (1881-1951) and Florence Muriel Wood (née Herington). He appears as Harold Baruch on the 1911 census.

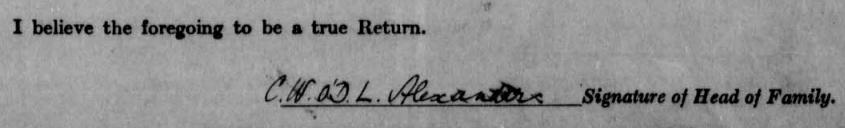

Interestingly, the Census form was signed by Talbot Wood so maybe BHs father also did not like his own first name! At the time of the Census the family lived at 30, Violet Bank Road, Nether Edge, Sheffield, S7 1RZ.

Welsh School Days

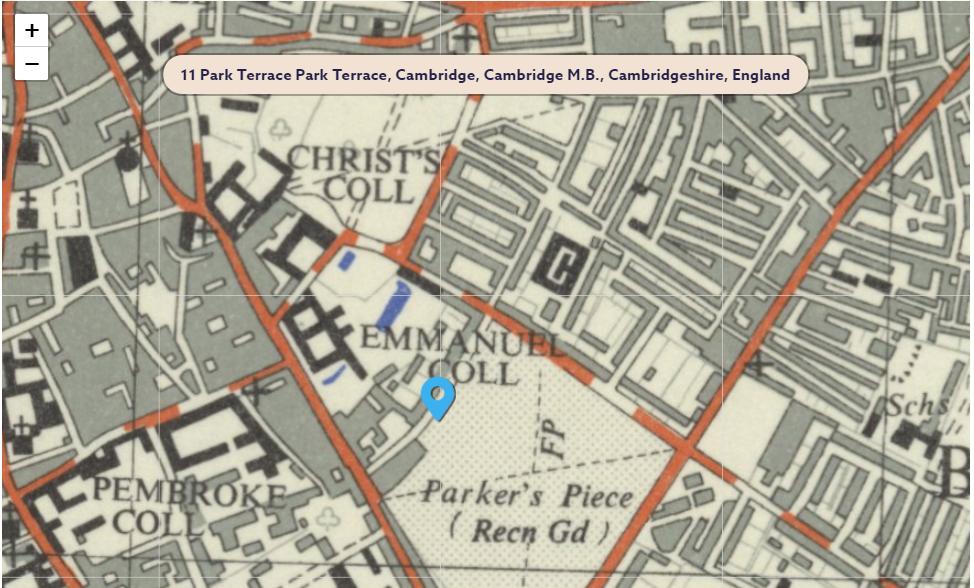

Baruch attended Friars School, Bangor (established in 1557) along with William Ritson Morry. BHW was one year and three months older than WRM so it is entirely possible that they had met.

Marriage to Marjory

In October 1936 BHW married Marjory Elizabeth Farrington in Ross, Herefordshire. When Marjory died on 7th September 1977 they were living at 146, Rectory Road, Sutton Coldfield, West Midlands. Baruch and Marjory had four children, FM Christopher Wood, Philip, Frank and Peggy.

Honours

In the 1984 New Years Honours List, Civil Division, BHW was awarded the OBE. The citation read simply : “For services to Chess”

He won the BCF President’s Award in 1983 alongside TJ Beach and Brian Reilly.

The 1946 Anglo-Soviet Radio Match

From The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match by Klein and Winter :

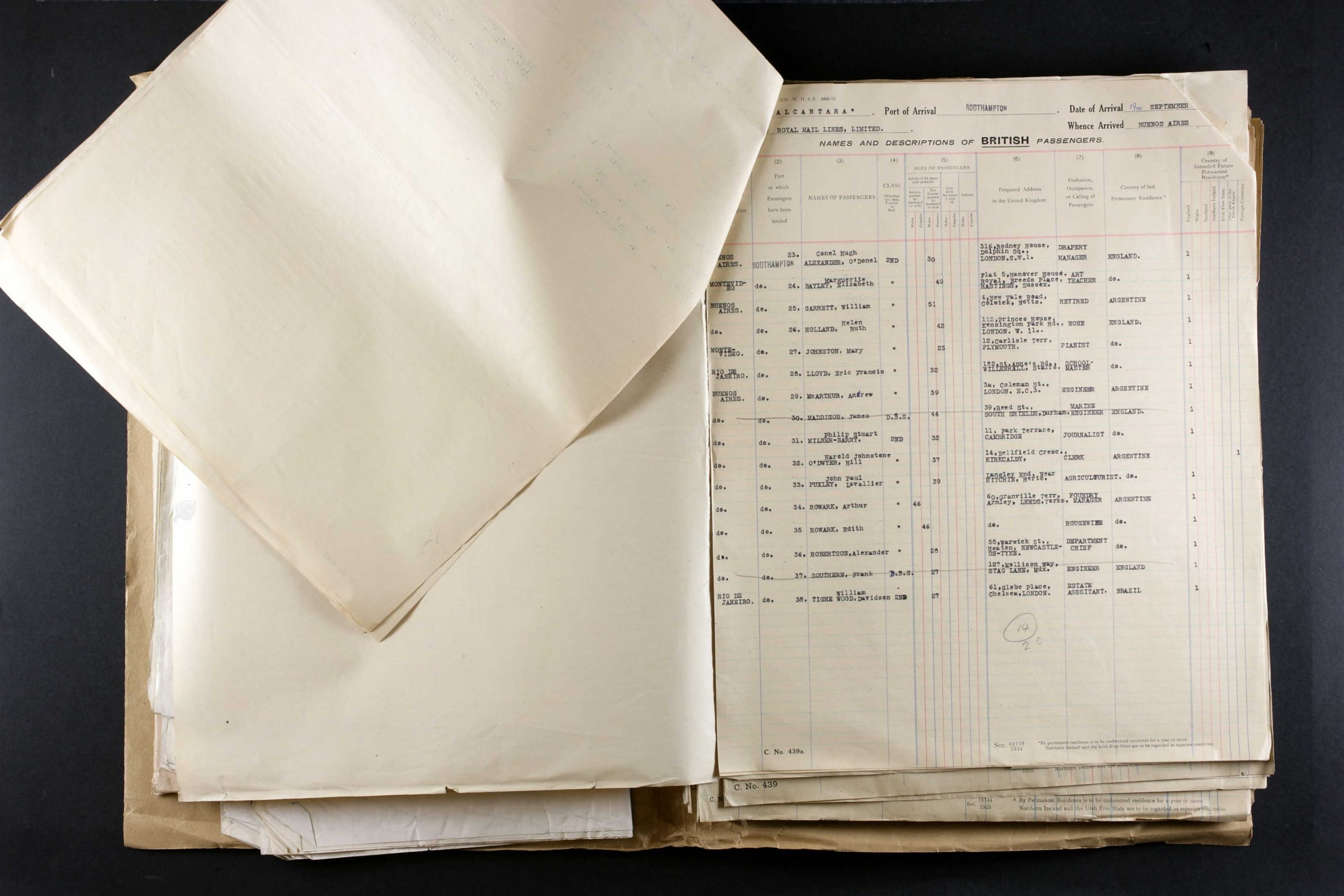

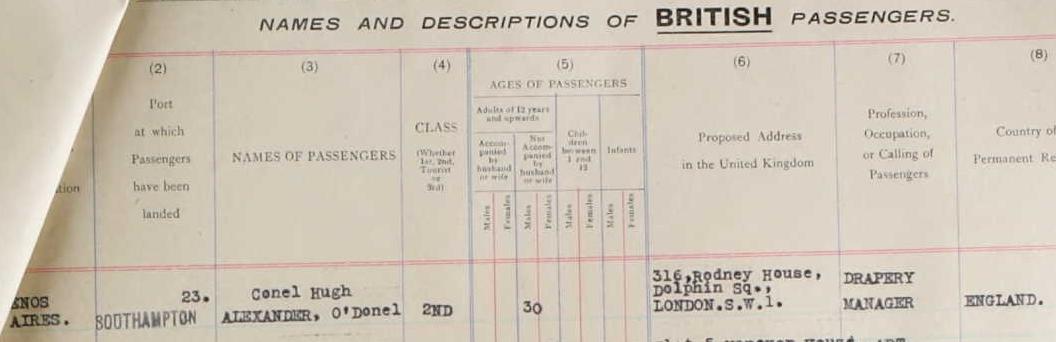

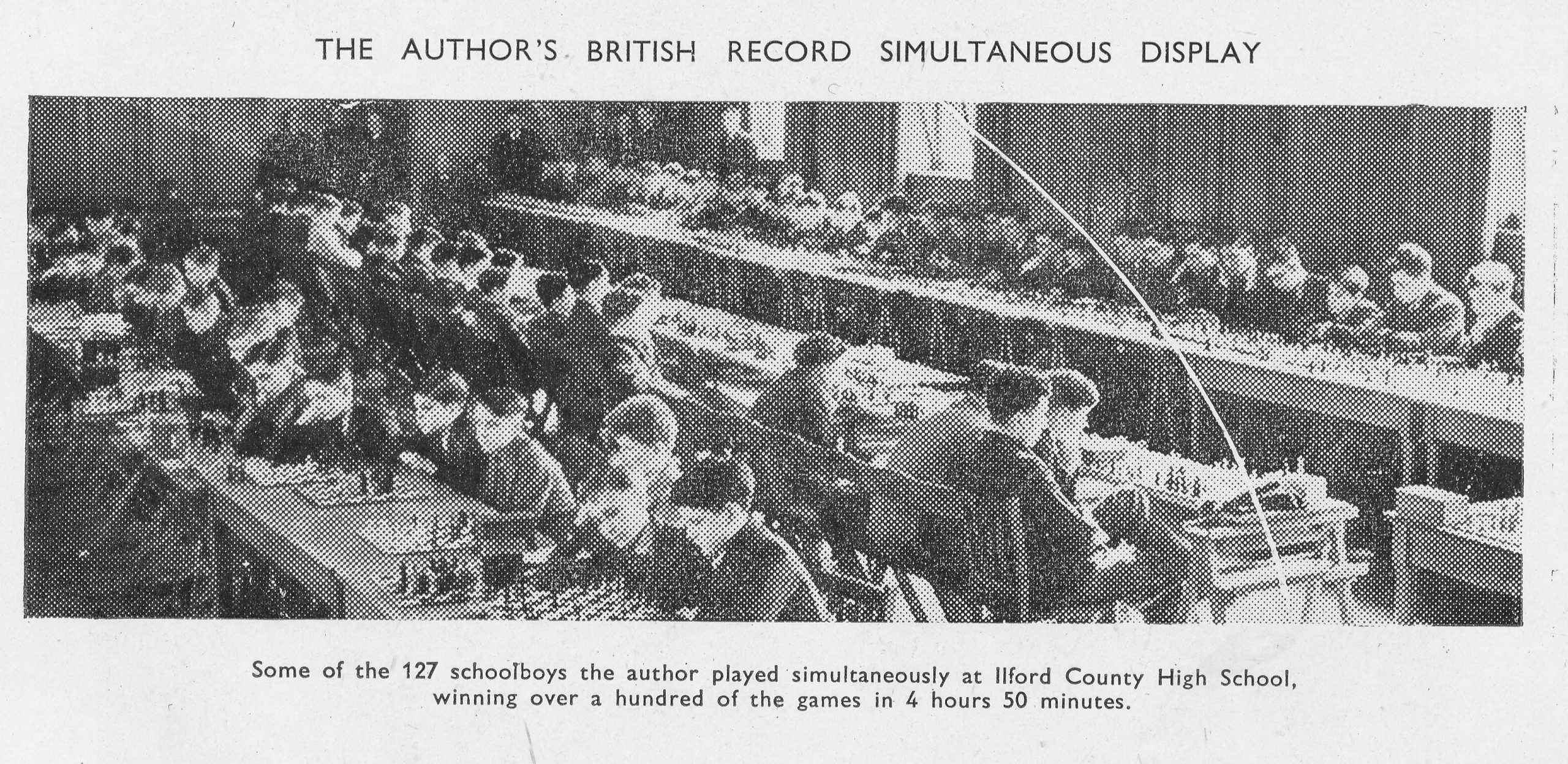

“BH Wood was born in Sheffield in 1909. A great lover of the game, he founded the magazine Chess in 1935, and has written a book for beginners. He scored a notable success by winning the British Correspondence Championship on one occasion. Wood has competed in the British Championship on several occasions, and in a number of Premier Reserves tournaments. He also played for Great Britain in the international team tournament (ed. Olympiad) at Buenos Aires in 1939.

He is a graduate of the University of Wales and Birmingham University. He has been very active in recent years in giving simultaneous exhibitions and in organising correspondence chess.”

Between 1938 and 1957, BH won the championship of Warwickshire eight times. He held the record (until 2006) for the most Birmingham & District Chess League Individual titles – nine, all won in Division 1: 1937, 1939, 1954, 1956, 1958, 1960, 1966, 1967, and 1983. He was the Records Secretary for the League from 1951-61.

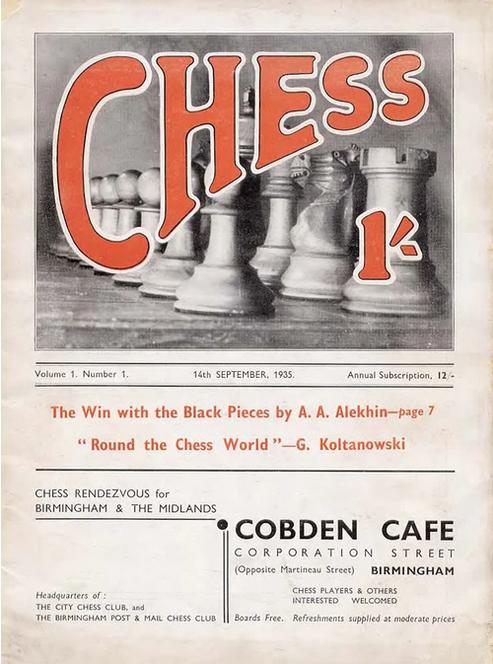

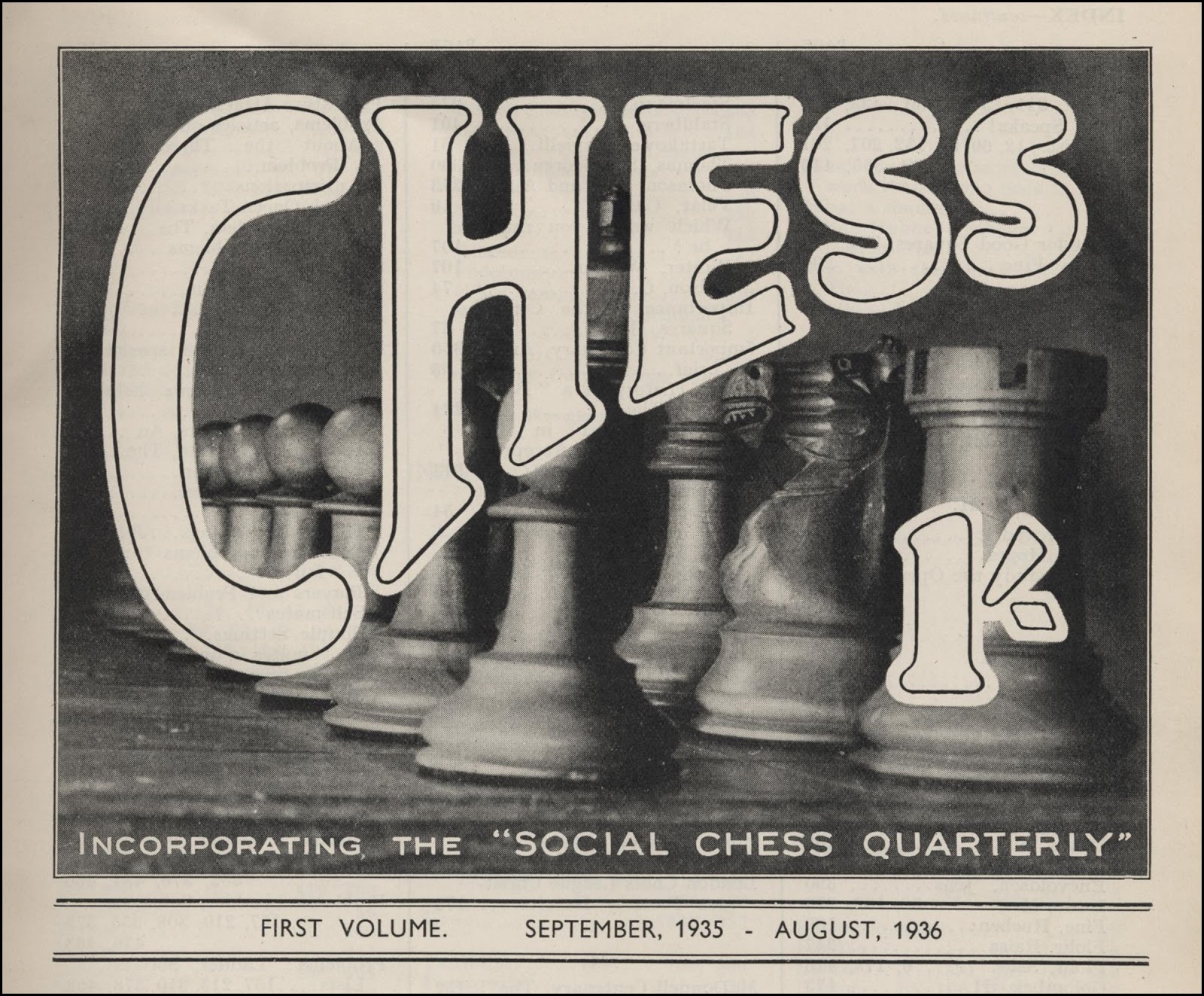

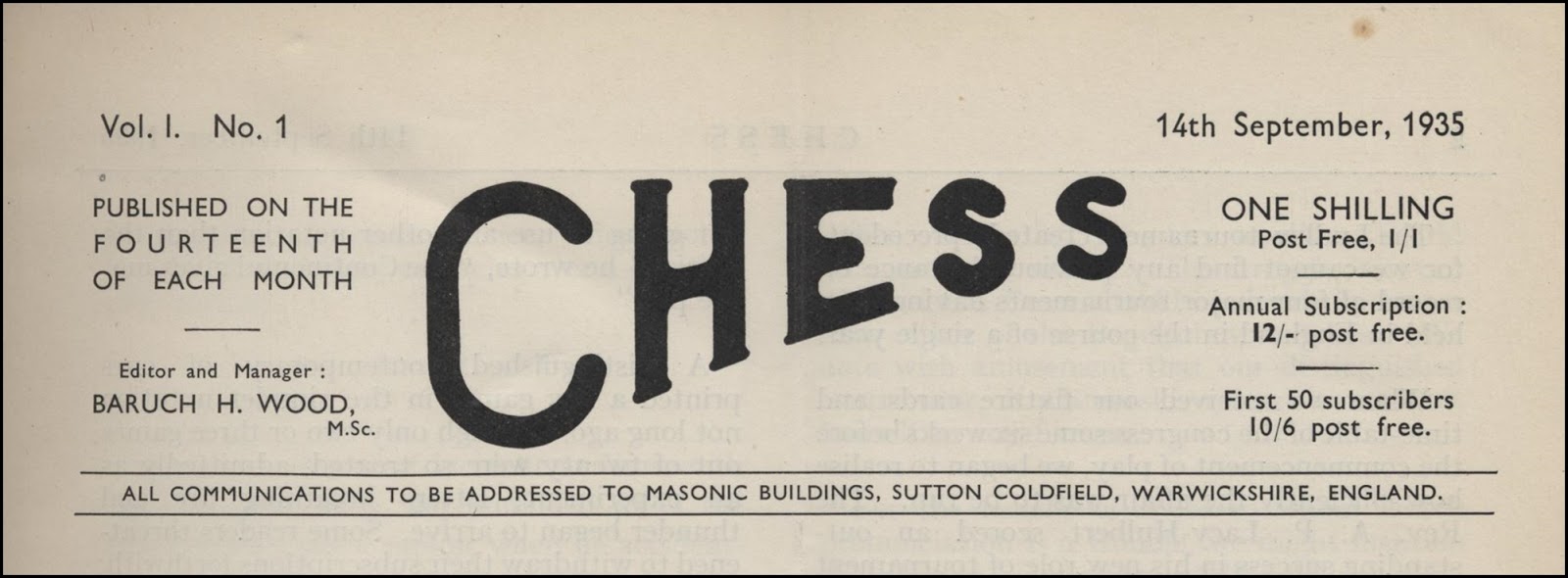

Birth of a Magazine

From CHESS, Volume 52 (1987), Number 1014-15 (Christmas), we have the very last issue of the magazine for which BH was the Editor before becoming Founding Editor (and Paul Lamford became Editor). BH wrote:

“Countless people have asked me ‘Why did you start CHESS?’ I was in love with university life and has just taken an M.Sc., a waste of time after a good first-class honours, and decided to have a go at replacing the old Chess Amateur, which had closed down. I had edited the students’ magazine in both Bangor and Birmingham. The first had been produced by The Daily Post Printers in Liverpool, who agreed to print 1,000 copies for £90. That £90 would be nearly £2,400 now.

A year’s subscription I announced as 10 shillings (50p).

Two bits of luck! J.H. Van Meurs, a Dutchman who did a lot for British Chess, had listed in his still young B.C.F. Year Book some hundreds of chess clubs.

W.H. Watts, another great figure of those days, had floated a rather short-lived magazine The Chess Budget, donated a ‘Budget Cup‘, for knock-out team competition and published excellent books on big tournaments, etc. He handed me a list of keen chess players all around the world. I spent a week addressing envelopes by hand to all the clubs and people.

To individuals I sent single copies of CHESS; to each club three copies, inviting payment or subscriptions. Hardly anybody failed to pay. Obviously there was a demand for a chess magazine with a lighter touch than the B.C.M.

Years later, I learnt why Mr. Watts had been so generous. He had fallen out with the establishment and welcomed the arrival of a new publication.

Within three months I was selling 3,000 copies an issue.

Some early ideas were chessy short stories , cartoons and a competition for humorous anecdotes.

I soon went to Amsterdam for the first Euwe-Alekhine match. I traced Alekhine to his hotel room with difficulty. He was officially incommunicado. He came to the door in pyjamas, and within five minutes we had agreed to a £5 article per month. I was, of course, already on conversational terms with him (and remained so!).

Now I fell into trap. 3,000 readers in four months meant 6,000 in eight months, 9,000 in a year…?

Not so! This is extrapolation, a matter of calculation full of risks.

My preparations had been too good. In the remaining eight months of the year I picked up only a thousand more readers. Alekhine lost the title. With three months to go, my money ran out, I struggled to the end of the year. The twelfth issue was pathetically thin compared with the first few but renewals staring rolling in and CHESS blossomed again.

The fifty-two years since have been gruelling, unremitting toil but fascinating interest. How we bought our own presses and the effect this had on the world’s chess press – A law suit that went to appeal – How CHESS linked people in Malta, Australia, Hungary – Adventures in ‘simuls’, postal chess etc. How we helped police to identify a drowned man, etc. So many tales to tell!

BHW

BCF Obituary

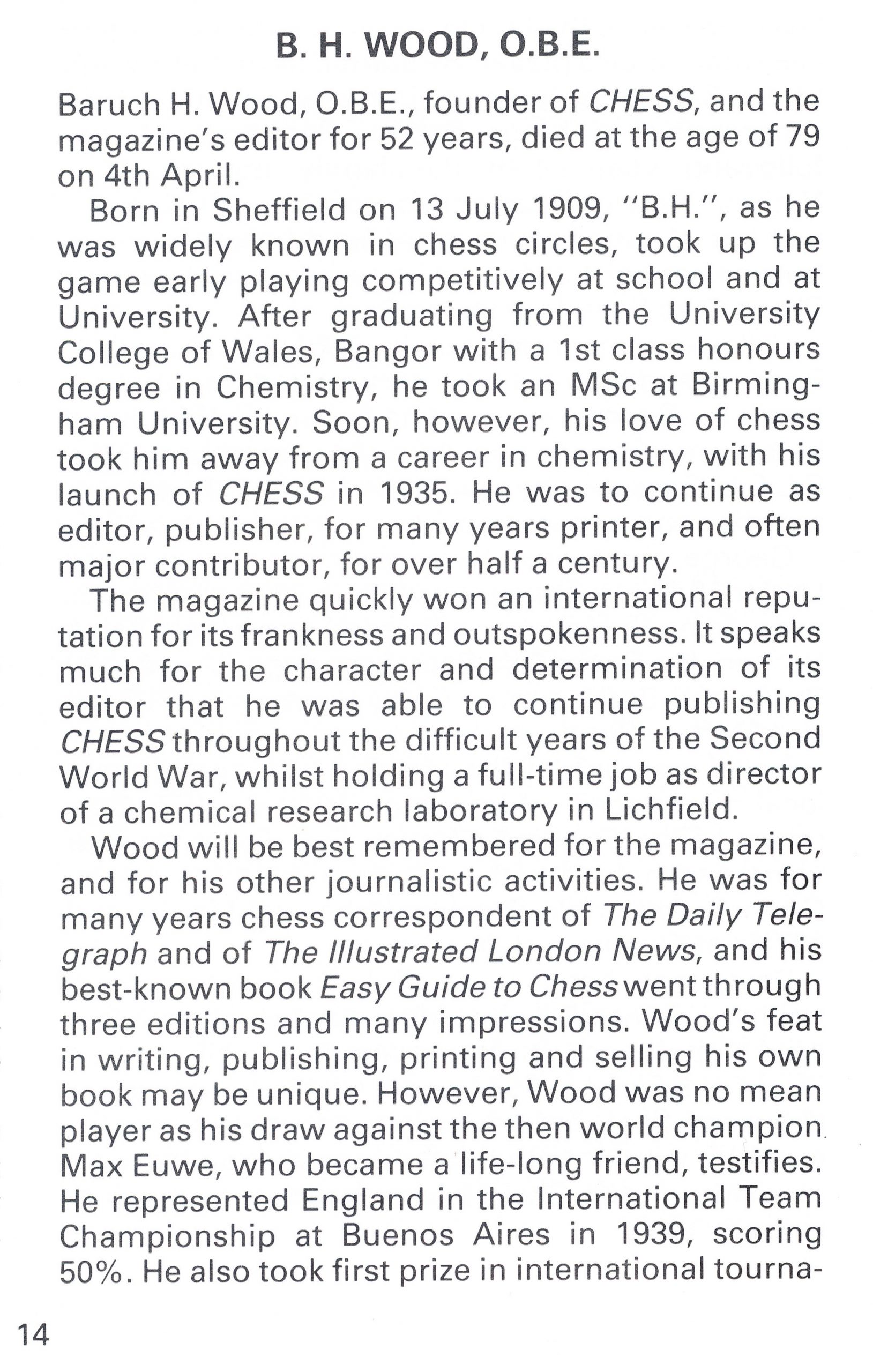

Here is an obituary from the BCF Yearbook 1989 – 1990, page 14 :

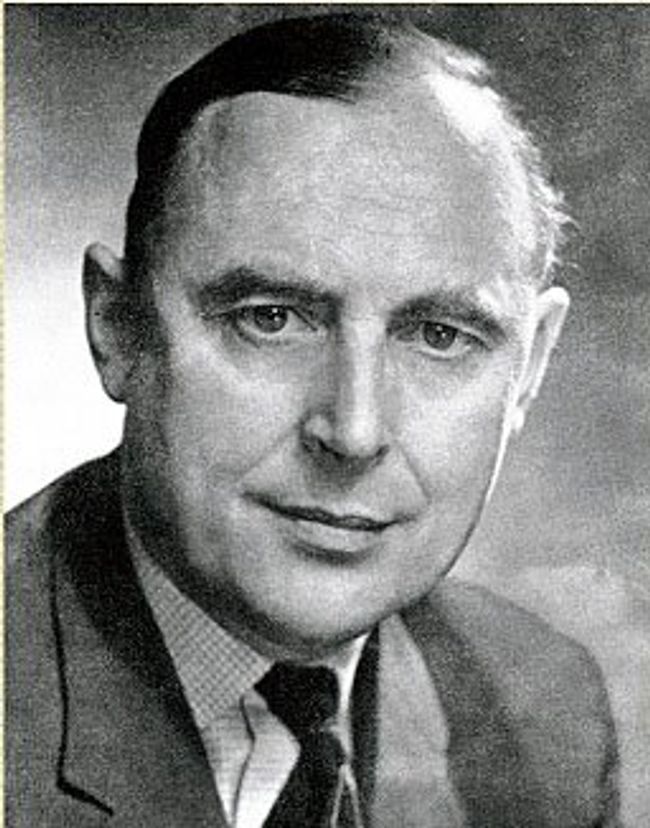

B.H. Wood, O.B.E

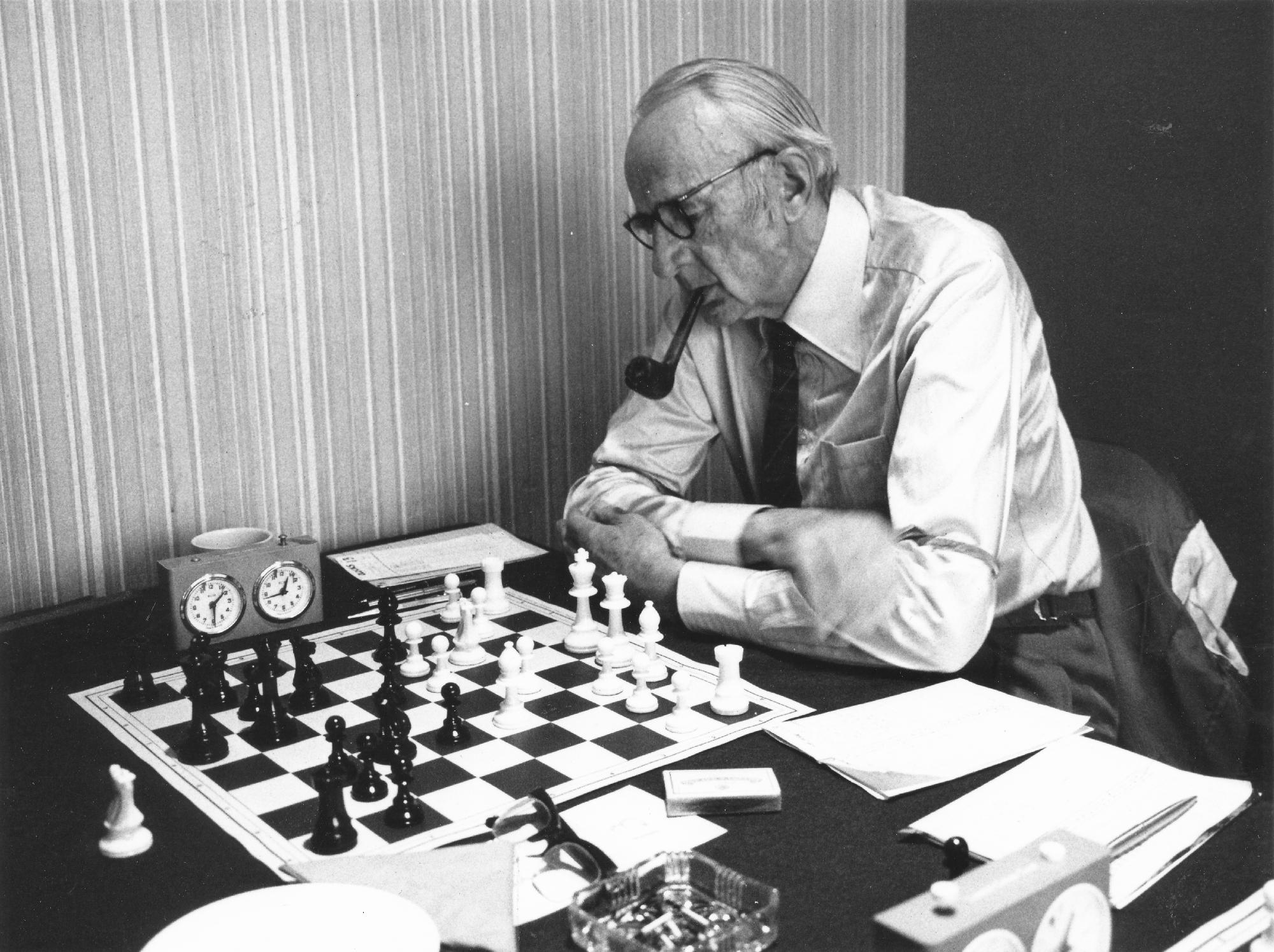

Baruch H. Wood, O.B.E., founder of CHESS, and the magazines editor for 52 years, died at the age of 79 on 4th April.

Born in Sheffield on 13 July 1909, “B.H.”, as he was widely known in chess circles, took up the game early playing competitively at school and at University. After graduating from the University College of Wales, Bangor with a 1st class honours degree in chemistry, he took an MSc at Birmingham University. Soon, however, his love of chess took him away from a career in chemistry, with his launch of CHESS in 1935. He was to continue as editor, publisher, for many years printer, and often major contributor, for over half a century.

The magazine quickly won an international reputation for its frankness and outspokenness. It speaks much for the character and determination of its editor that he was able to continue publishing CHESS throughout the difficult years of the Second World War, whilst holding a full-time job as director of a chemical research laboratory in Lichfield.

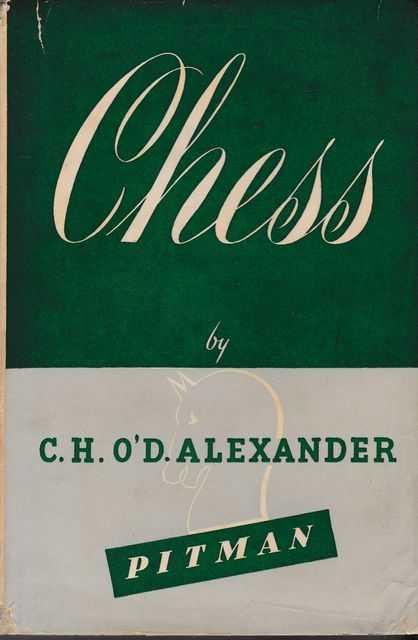

Wood will be best remembered for the magazine, and for his other journalistic activities. He was for many years chess correspondent of The Daily Telegraph and of The Illustrated London News, and his best known book Easy Guide to Chess went through three editions and many impressions.

The above book (albeit the later Cadogan version) is available online.

Nigel Davies wrote “One of the best beginners books on the market.”

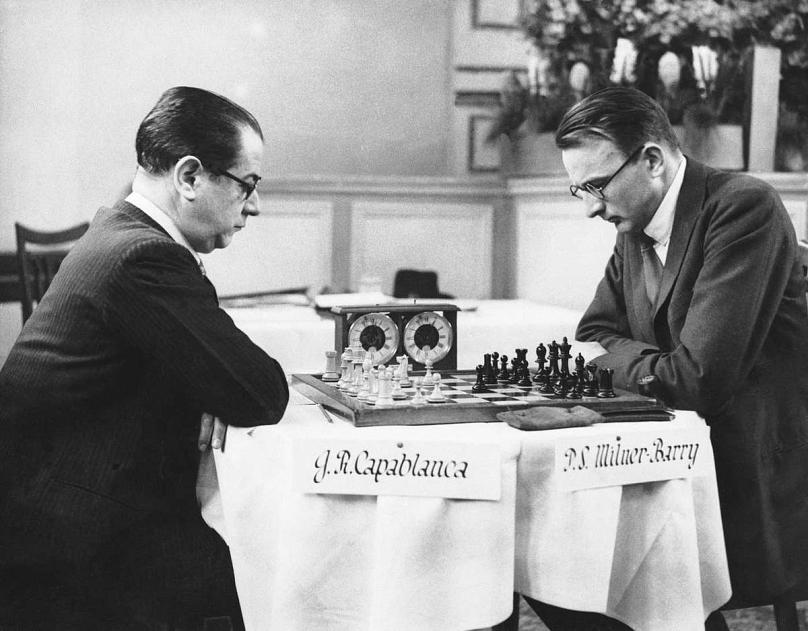

Wood’s feat in writing, publishing, printing and selling his own book may be unique. However, Wood was no mean player as his draw against the then world champion Max Euwe, who became a life-long friend, testifies.

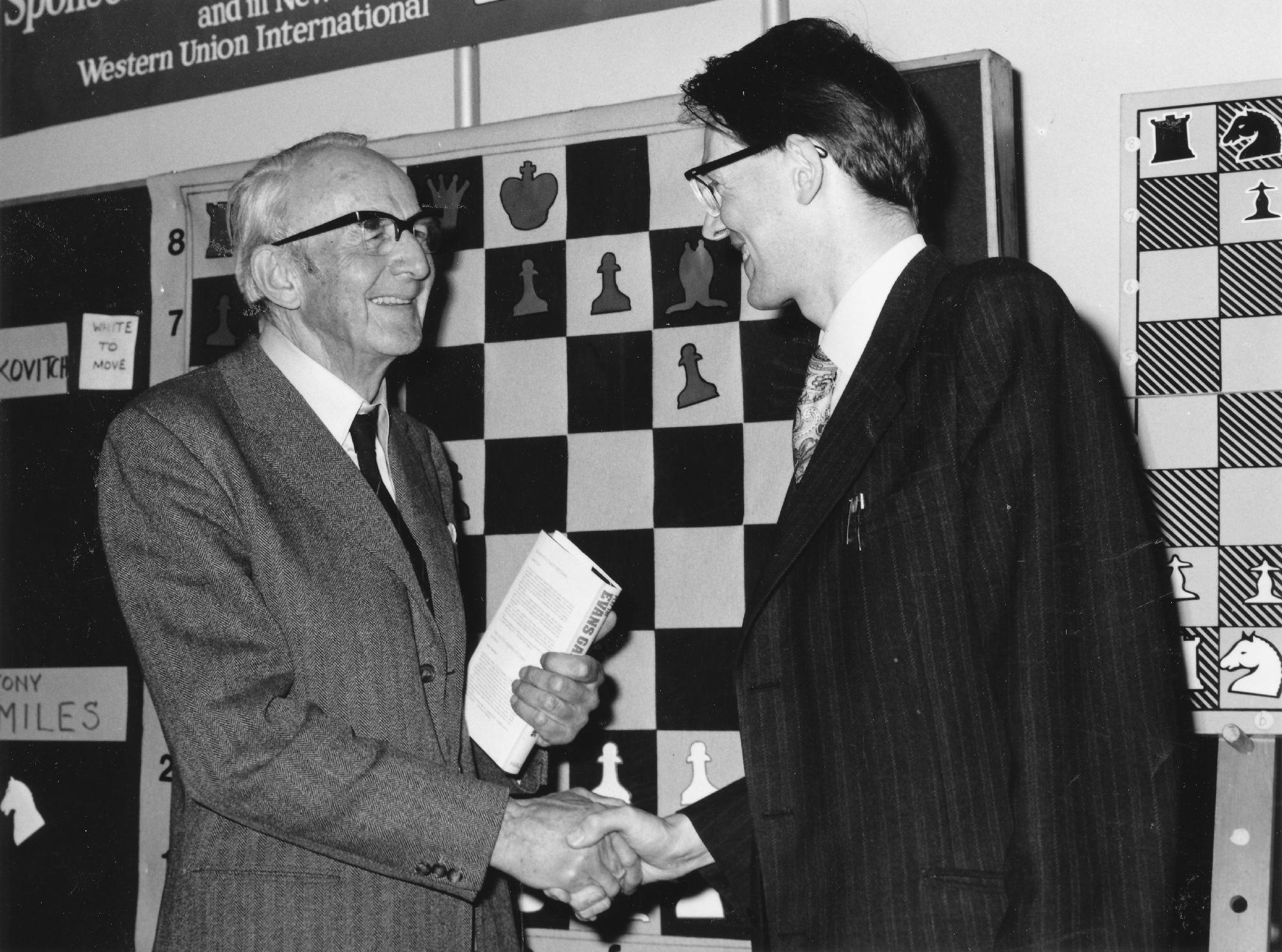

He represented England in the International Team Championship at Buenos Aires in 1939, scoring 50%. He also took first prize in international tournaments at Baarn 1947, Paignton 1954, Whitby 1963, Thorshavn 1967 and Jersey 1975 and was second in the 1948 British Championship. He was British Correspondence Chess Champion in 1945.

A life member of F.I.D.E. Wood was also an International Arbiter, and organised 21 annual chess festivals at seaside venues from the 50’s onwards. In addition he was an active behind-the-scenes inspirer of many chess events, and in particular was known as a driving spirit of university chess, being until the time of his death President of the British University Chess Association.

He founded the Postal Chess Club and League and was for many years President of the British Postal Chess Federation.

He was awarded the O.B.E. for services to chess in 1984.

His wife Marjory, predeceased him; he leaves three sons Christopher, Frank and Philip, and a daughter Peggy.

and here is the article as it appeared in the Yearbook.

Golombek on Wood

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977) by Harry Golombek :

“A well known British player, editor of Chess (starting 1935) and chess correspondent of The Daily Telegraph and Illustrated London News. A FIDE judge, he has founded and conducted 21 annual chess festivals, notably at Whitby, Eastbourne and Southport.

Winner of a number of small and semi-international tournaments : Baarn 1947, Paignton 1954, Whitby 1963, Thorshavn 1967, and Jersey 1975.

Played for the BCF in the International Team Tournament at Buenos Aires 1939. His best tournament result was probably his equal second in the British Championship at London 1948.

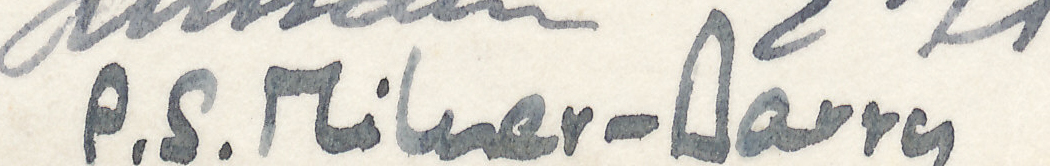

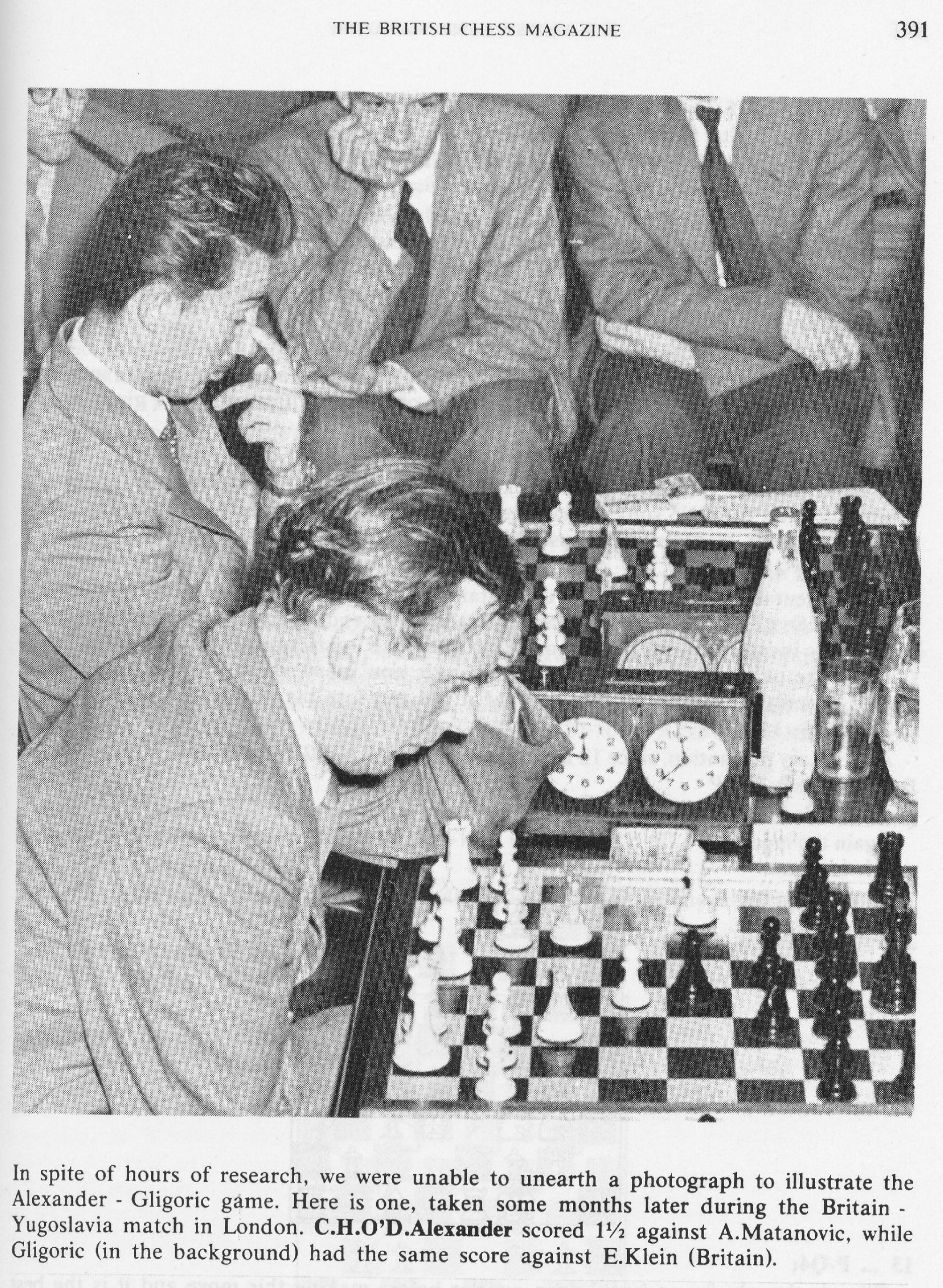

In 1954 BHW was sued BH Wood for libel by William Ritson Morry over a letter BHW sent to Henry Golding of the Monmouthshire County Chess Association warning him of WRMs financial history. Here is a summary of the action :

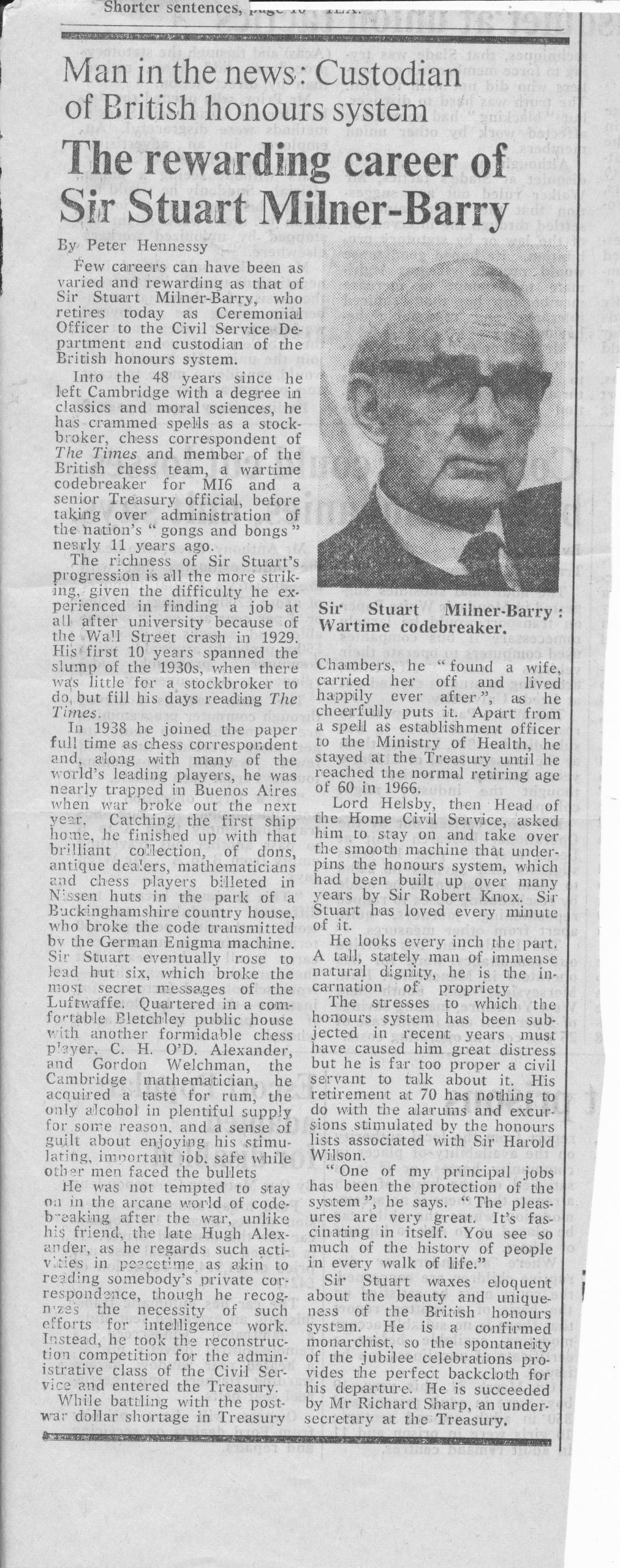

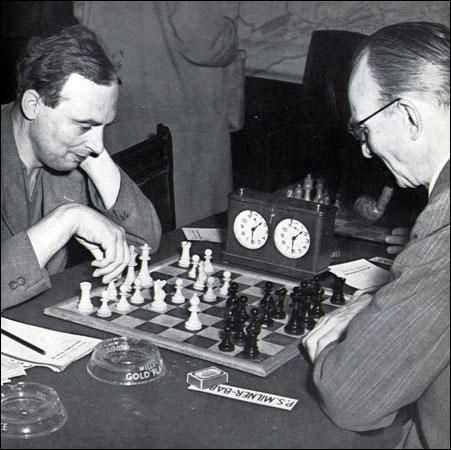

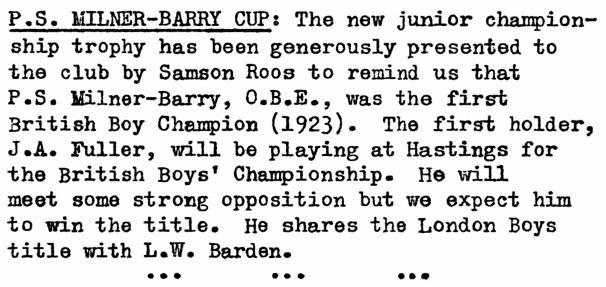

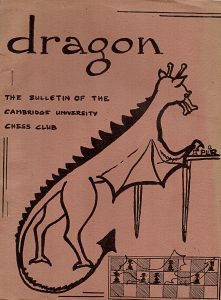

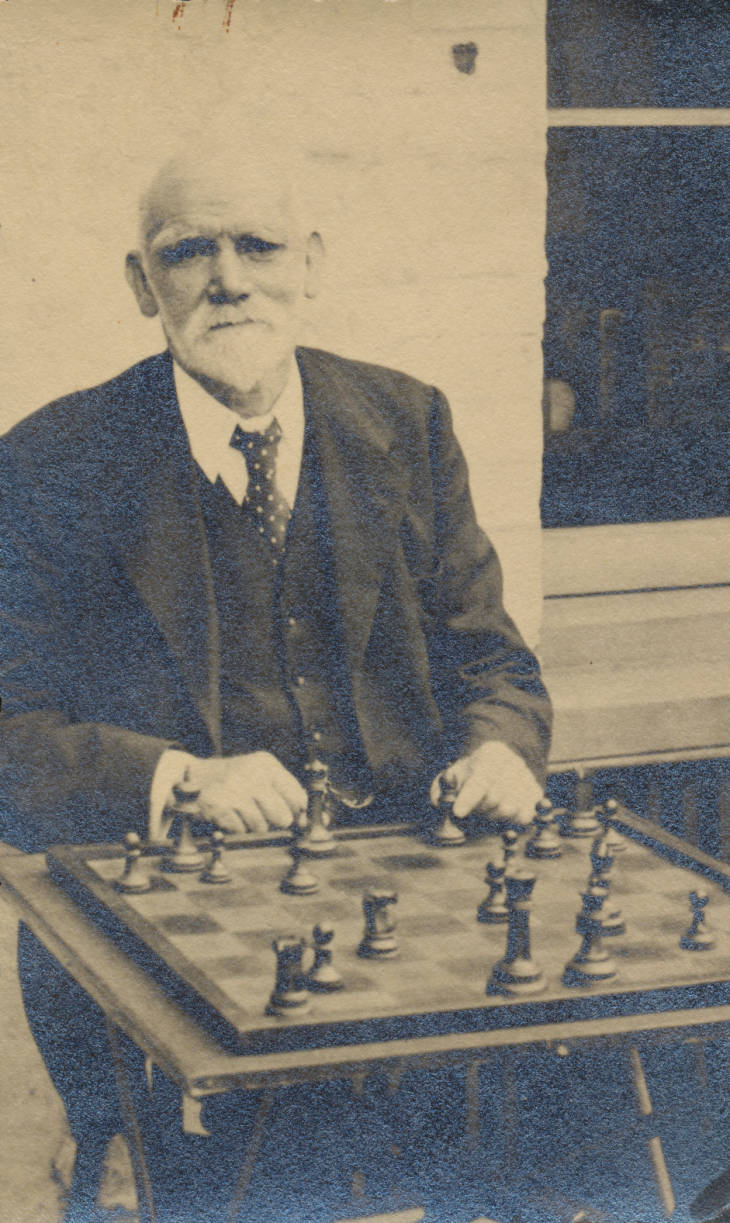

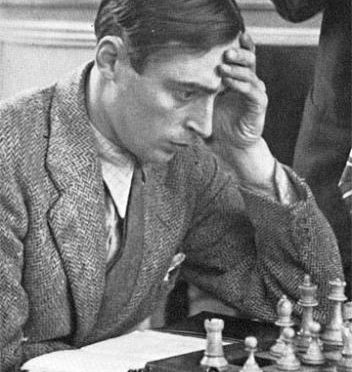

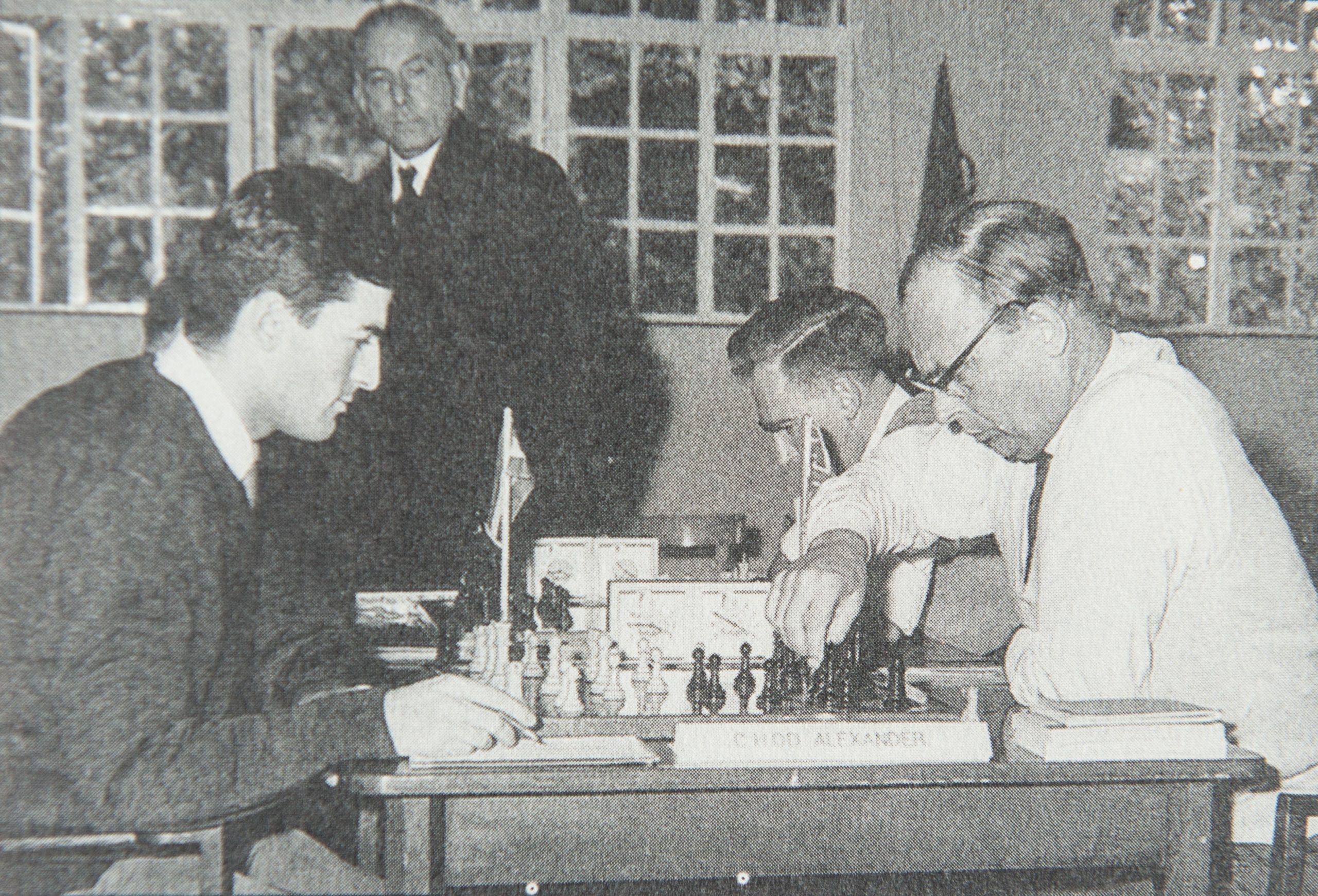

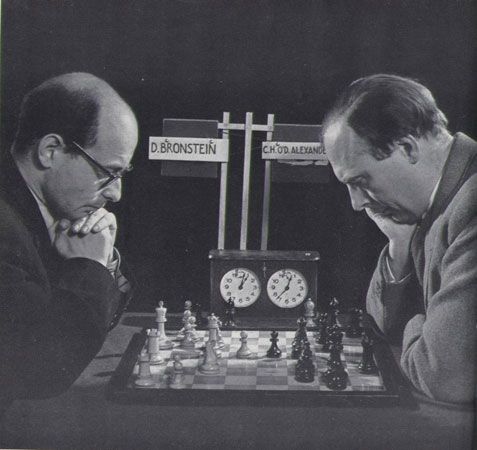

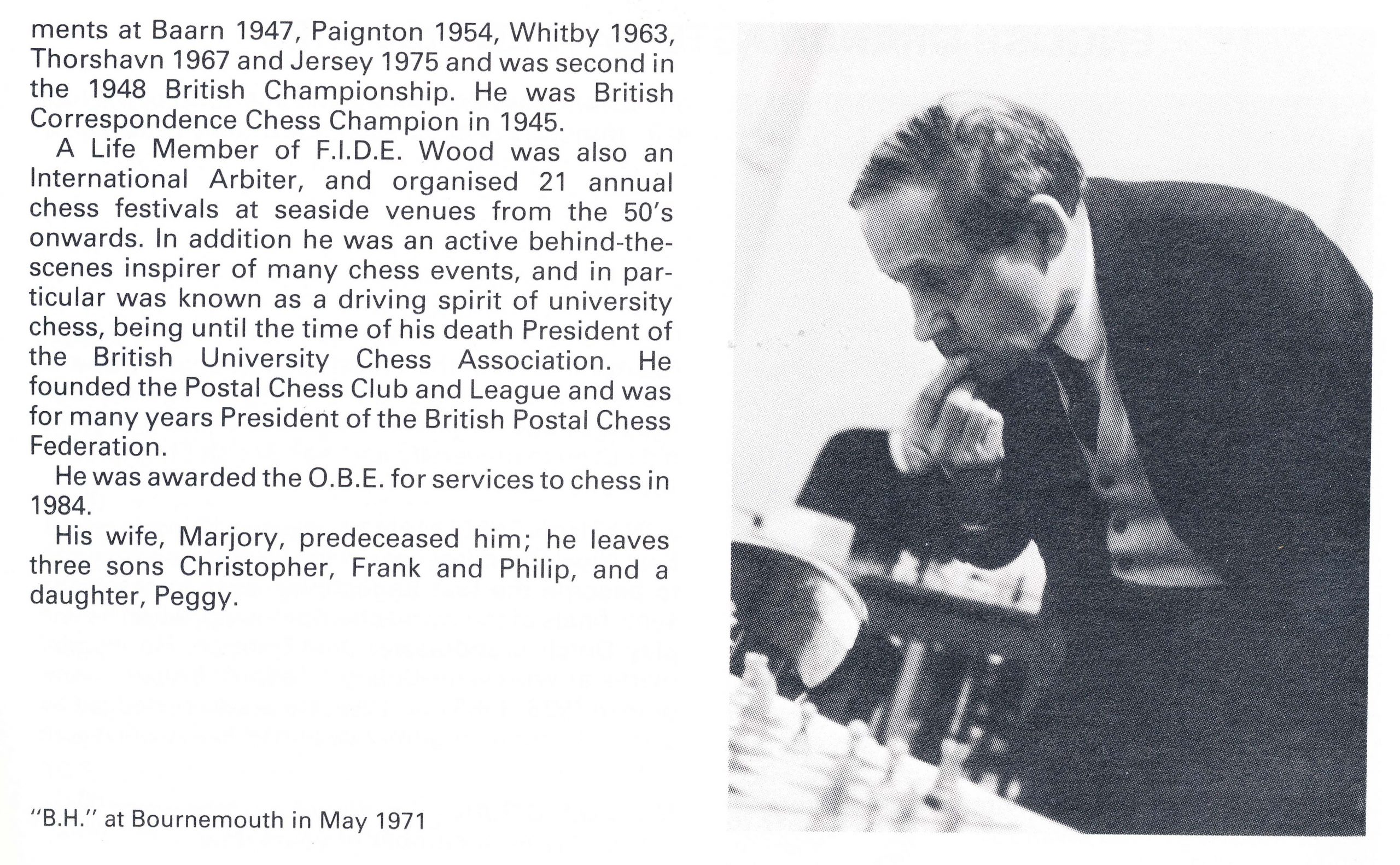

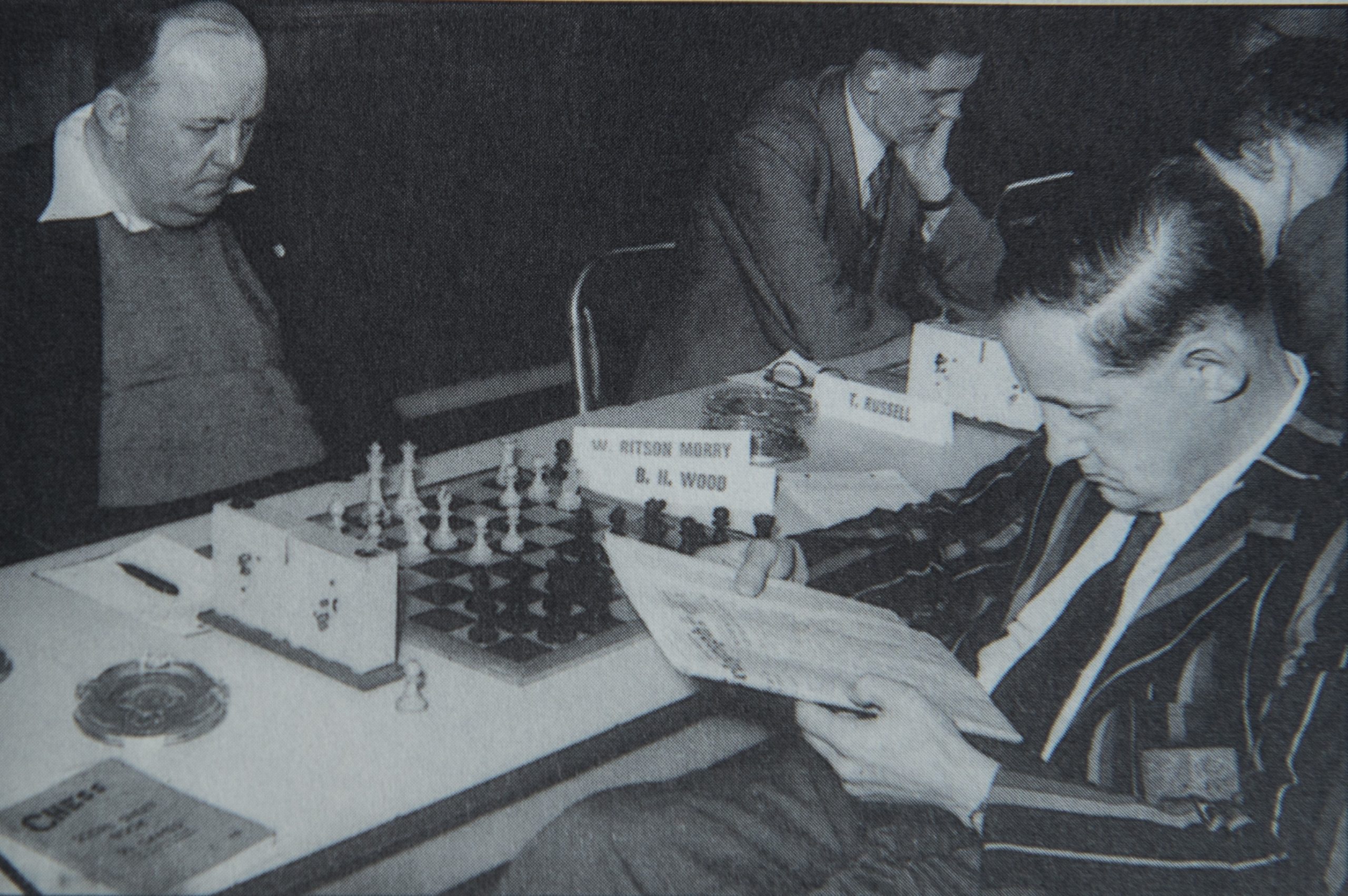

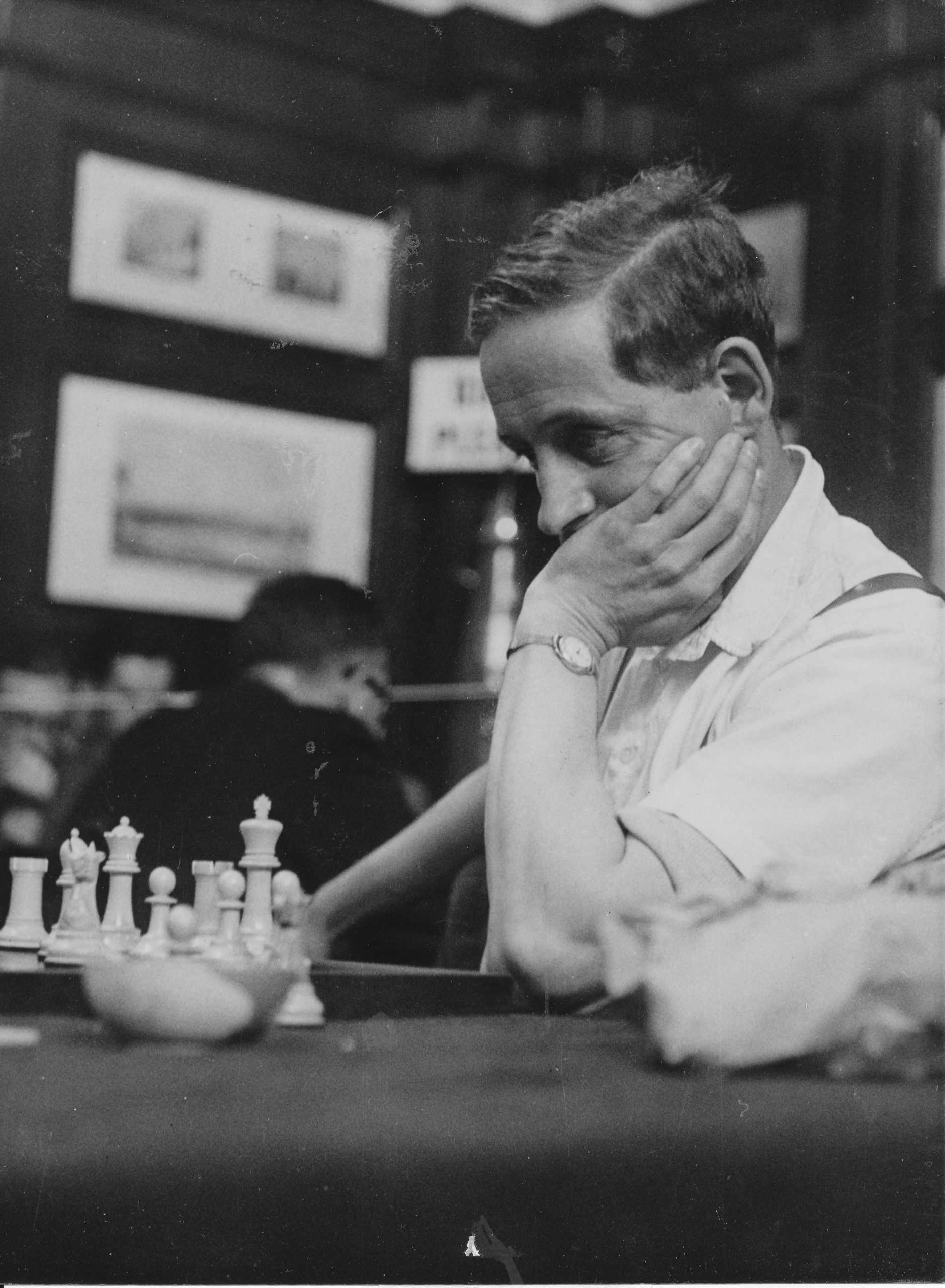

and two years later in 1956 we have this telling photograph of Ritson and BH playing at the British Championships in Blackpool. It must have been an entertaining pairing for the organisers if no-one else!

Possibly WRM was thinking this as they played:

Among his books are : Easy Guide to Chess, Sutton Coldfield 1942 et seq; World Championship Candidates Tournament 1953, Sutton Coldfield 1954. “

Cafferty on Wood (1989)

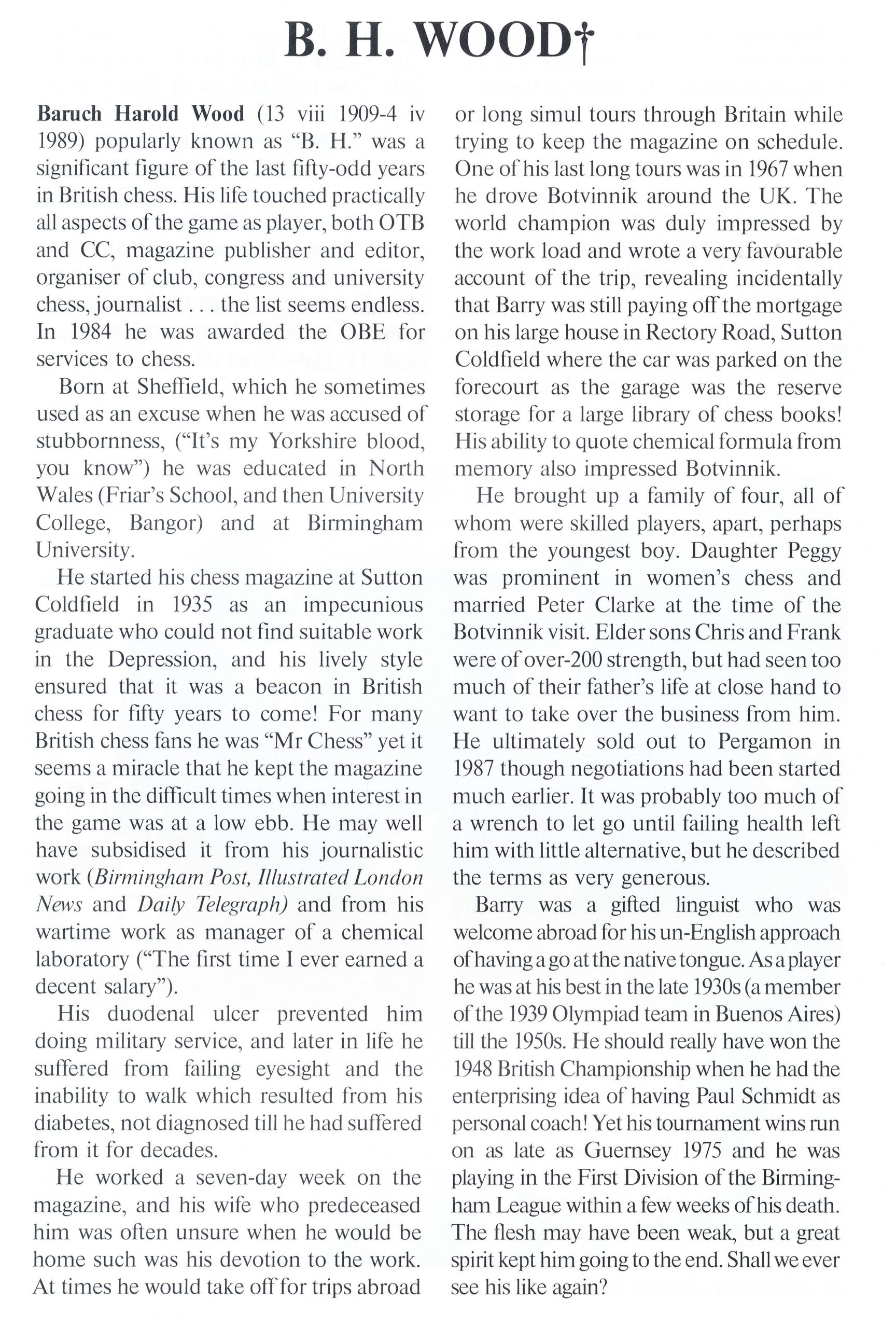

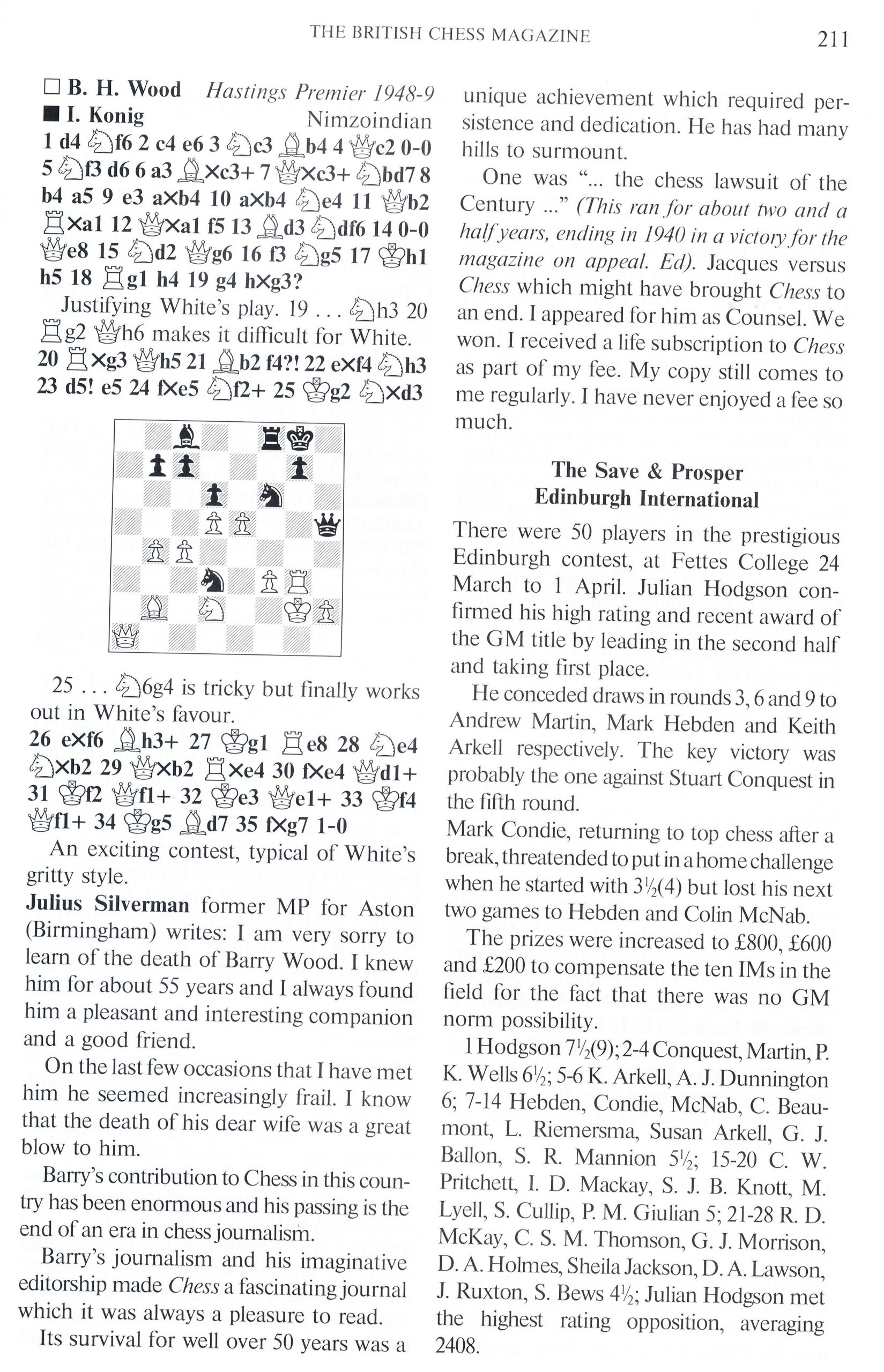

Here is the obituary from British Chess Magazine, Volume CIX (1989, 109), Number 5 (May), pages 210 – 211:

B. H. WOOD

Baruch Harold Wood (13 viii 1909-4 iv 1989) popularly known as “B. H.” was a significant figure of the last fifty-odd years in British chess. His life touched practically all aspects of the game as player, both OTB and CC, magazine publisher and editor, organiser of club, congress and university chess, journalist . . . the list seems endless. In 1984 he was awarded the OBE for services to chess.

Born at Sheffield, which he sometimes used as an excuse when he was accused of stubbornness, (“It’s my Yorkshire blood, you know”) he was educated in North Wales (Friar’s School, and then University College, Bangor) and at Birmingham University.

He started his chess magazine at Sutton Coldfield in 1935 as an impecunious graduate who could not find suitable work in the Depression, and his lively style ensured that it was a beacon in British chess for fifty years to come! For many British chess fans he was “Mr Chess” yet it seems a miracle that he kept the magazine going in the difficult times when interest in the game was at a low ebb. He may well have subsidised it from his journalistic work (Birmingham Post, Illustrated London News and Daily Telegraph) and from his wartime work as manager of a chemical laboratory (“The first time I ever earned a decent salary”).

His duodenal ulcer prevented him doing military service, and later in life he suffered from failing eyesight and the inability to walk which resulted from his diabetes, not diagnosed till he had suffered from it for decades.

He worked a seven-day week on the magazine, and his wife who predeceased him was often unsure when he would be home such was his devotion to the work. At times he would take off for trips abroad or long simul tours through Britain while trying to keep the magazine on schedule.

One of his last long tours was in 1967 when he drove Botvinnik around the UK. The world champion was duly impressed by the work load and wrote a very favourable account of the trip, revealing incidentally that Barry was still paying off the mortgage on his large house in Rectory Road, Sutton Coldfield where the car was parked on the forecourt as the garage was the reserve storage for a large library of chess books! His ability to quote chemical formula from memory also impressed Botvinnik.

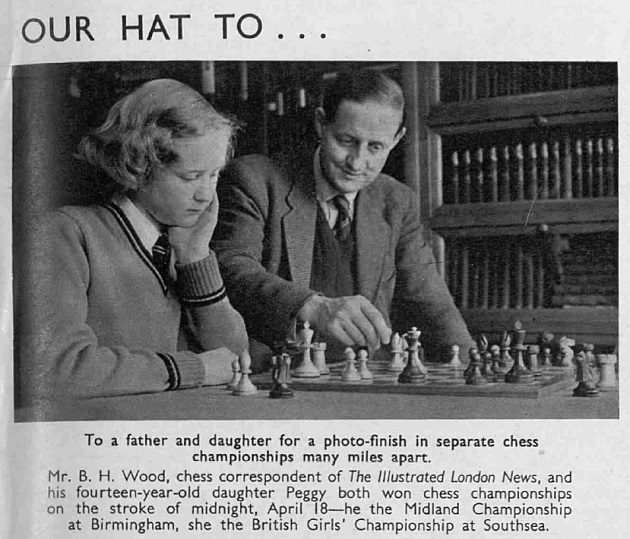

He brought up a family of four, all of whom were skilled players, apart, perhaps from the youngest boy. Daughter Peggy

was prominent in women’s chess and married Peter Clarke at the time of the Botvinnik visit. Elder sons Chris and Frank were of over-200 strength, but had seen too much of their father’s life at close hand to want to take over the business from him. He ultimately sold out to Pergamon in 1987 though negotiations had been started much earlier. It was probably too much of a wrench to let go until failing health left him with little alternative, but he described

the terms as very generous.

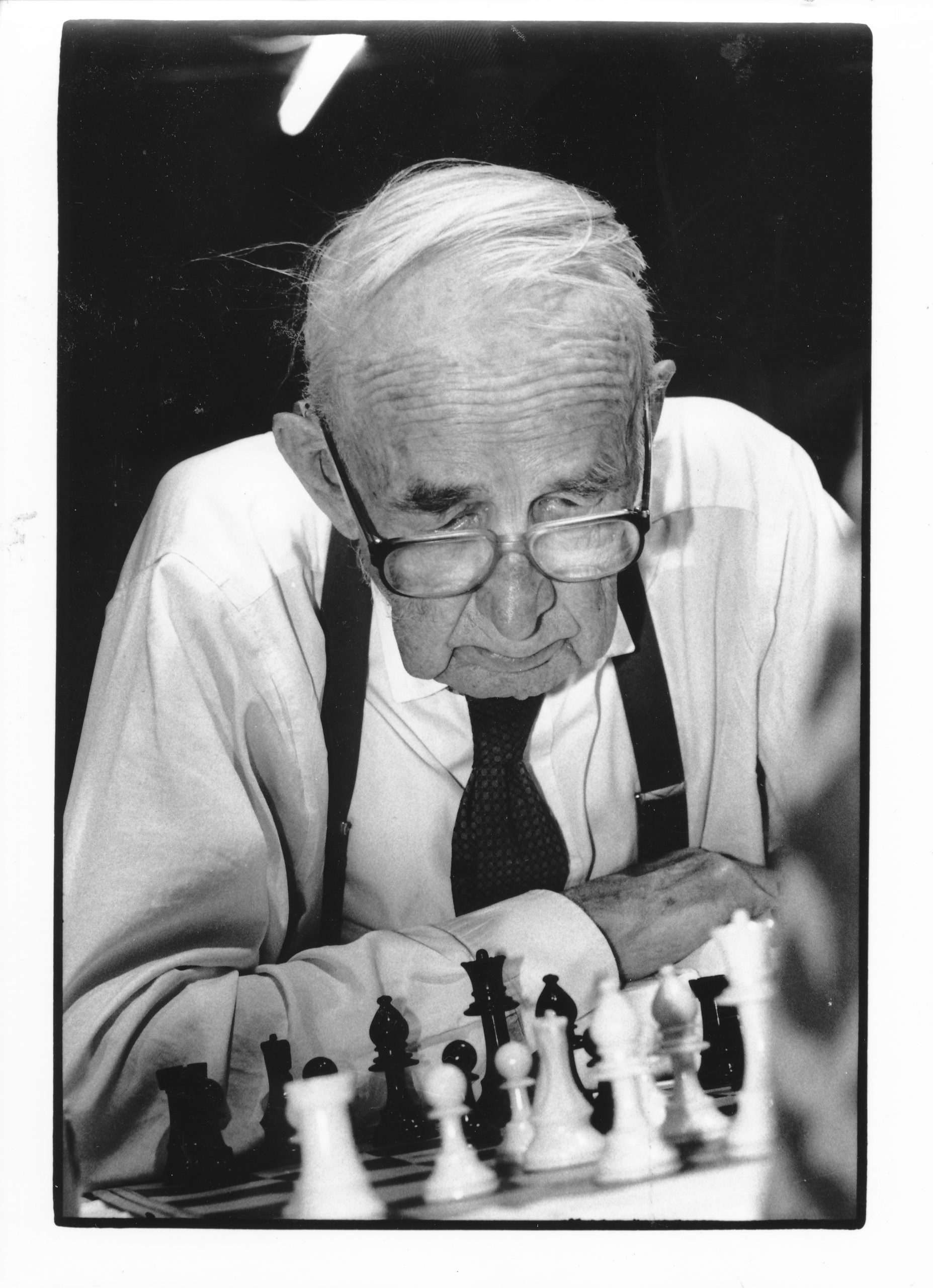

Barry was a gifted linguist who was welcome abroad for his un-English approach of having a go at the native tongue. As a player he was at his best in the late 1930s (a member of the 1939 Olympiad team in Buenos Aires) till the 1950s. He should really have won the 1948 British Championship when he had the enterprising idea of having Paul Schmidt as personal coach! Yet his tournament wins run on as late as Guernsey 1975 and he was playing in the First Division of the Birmingham League within a few weeks of his death. The flesh may have been weak but a great spirit kept him going to the end.

Shall we ever see his like again?

Julius Silverman former MP for Aston (Birmingham) writes: I am very sorry to learn of the death of Barry Wood. I knew him for about 55 years and I always found him a pleasant and interesting companion and a good friend. On the last few occasions that I have met him he seemed increasingly frail. I know that the death of his dear wife was a great blow to him.

Barry’s contribution to Chess in this country has been enormous and his passing is the end of an era in chess journalism.

Barry’s journalism and his imaginative editorship made Chess a fascinating journal which it was always a pleasure to read.

Its survival for well over 50 years was a unique achievement which required persistence and dedication. He has had many

hills to surmount.

One was “… the chess lawsuit of the Century …” (This ran for about two and a half years, ending in 1940 in a victory for the magazine on appeal, Ed). Jacques versus Chess which might have brought Chess to an end. I appeared for him as counsel. We won. I received a life subscription to Chess as part of my fee. My copy still comes to me regularly. I have never enjoyed a fee so much.

Here is the article in its original form:

Bernard on Barry (2004)

REMEMBERING BARRY WOOD (1909-1939)

by Bernard Cafferty

One of the most influential figures in British chess of the 20th century was B. H. Wood, whom I knew personally from 1951, and whom I played regularly, over a period of three decades, till l moved from Birmingham to Hastings in 1981. Here are some

memories of the man who was thought of by many in Britain as “Mr Chess”.

Born in Sheffield, Baruch Harold Wood had his secondary education in North Wales at the same grammar school as W Ritson

Morry who was later to become his Midlands colleague and bitter rival. BH always attributed his well-known stubbornness (he never resigned early) to “his Yorkshire blood”. Wood and Morry were to be students together at Birmingham University after BH gained his BSc in Wales. Then the pair faced the hard task of finding work in depression-struck mid-1930s England. BH founded his monthly magazine CHESS in 1935, an act of amazing optimism which only his great appetite for work could justify. The magazine was based in Sutton Coldfield, just north of Birmingham, at gloomy premises known as Masonic Buildings.

The early decades of this publication were marked by the outpouring of glorious journalism of a popular sort. The man’s love

of the game shone through his work and he recruited such contributors as the chatty Koltanowski and the prince of annotators

Alexander Alekhine. Later he became the long-serving columnist of the Birmingham Post, from 1949 of the weekly Illustrated London News, and even later of the Daily Telegraph. A feature of the magazine was its lively letters from readers which made for more interesting reading than the equivalent occasional letter to be found in the staid

BCM. The readers also made pertinent contributions to opening theory, especially in going through the 1946 MCO with a fine toothcomb and reporting their discoveries to Sutton Coldfield.

BH wrote a best-selling Easy Guide to Chess which went through several editions and was far more user-friendly than other primers on the market at the time. He also designed a luxury set, the Coldfield, and produced various chess clocks with new features. BH was a member of the BCF Olympiad side that played in the first part of the Buenos Aires Olympiad in the autumn of 1939. After the team’s withdrawal due to the outbreak of war, he stayed on in Argentina for a short while, taking part in a short tournament where he met the legendary Alekhine.

BH was married to Marjorie, a Birmingham primary school teacher, and had three sons and a daughter. The elder two boys,

Chris and Frank, were strong players but not Philip. His daughter Peggy was our leading girl player of the 1950s, and married Peter Clarke in 1962. One should note that BH was not Jewish, as many assumed from the name Baruch – he was generally addressed as Barry by his wife and close friends. Others called him just by the initials BH. Everyone in British chess knew exactly who you meant when you said BH. Many thought of him as a sharp business-man. In any event, the fearsome workload he shouldered meant that none of his children, seeing this at first hand, aspired to carry on the magazine as a family business. To many in the British chess community who had never seen top players in action, BH was their first contact with the wider chess world due to the exhausting simul tours he made to many clubs the length and breadth of the UK.

Later, he organized CHESS Festivals starting from 1953. These were our earliest open tournaments, held at attractive venues such as Cheltenham, Whitby, Eastbourne and Southport. These events created the opportunity for British amateurs to meet continental grandmaster opposition like Donner and O’Kelly. BH had great confidence in his ability – his MSc at Birmingham University was in chemistry, but in 1946-7 he started studying nuclear physics privately, telling Brian Reilly, who was employed by him at that time, that it was the science of the future. I have to simply marvel at this – where did he find the time? In his self-portrait in connection with the GB-USSR match of 1946 he revealed that he had been studying Russian privately with a view to taking an external degree in it at Birmingham University.

The post-war decade saw him at his most active. He was BCF delegate at early FIDE meetings post-1946, the period that saw the mighty Soviet Union admitted to membership in 1947. BH was instrumental in maintaining Spain’s membership of FIDE at the same time, despite Soviet opposition to Franco’s fascism. He claimed to me he was always a most welcome guest in Spain thereafter.

Battles with the BCF

BH had been exempt from military service due to a duodenal ulcer. He spent the war keeping the magazine alive in his spare time as he was put in charge of a research laboratory at the Birmingham Chemical Company. During the war the government had the power under emergency legislation to direct citizens into any sort of work that would contribute to the war effort. His comment to me on that intensive period was: “It was the first time I ever drew a decent salary”. After a short spell as BCF FIDE delegate, he fell out with the ruling body in the early 1950s. His view was that the national body was ultra-conservative and not open to fresh ideas such as the knockout championship open to all which he organised in 1949-50. Lo and behold, a few months later the BCF started organising regional competitions to arrange for qualification for the British Championship! BH often criticised the BCF in his magazine. In June 1950 he wrote the first of a planned series of articles on the evergreen theme “Where is British Chess Going?” and forwarded a copy to the BCF just before publication. The BCF legal eagle Professor Wheatcroft immediately threatened to take out an injunction, so putting the frighteners on the printers. Rather than delay the July issue (not that subscribers were not used to a rather irregular schedule!), BH brought out the issue with white space, on two pages, a dramatic way of alerting the readers to the dispute. The promised articles, which he said would appear after the dispute was settled, never appeared.

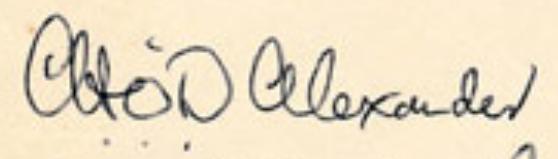

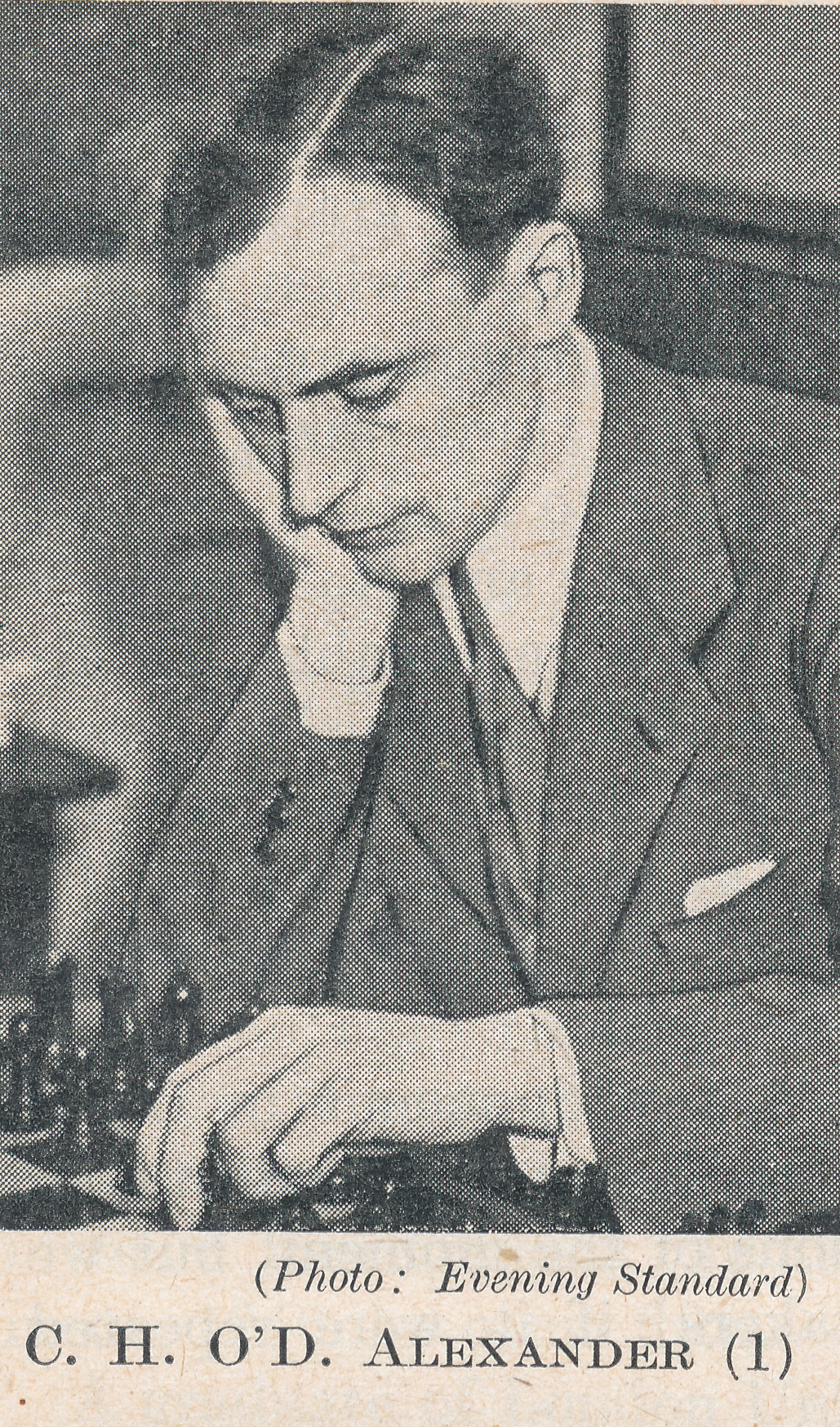

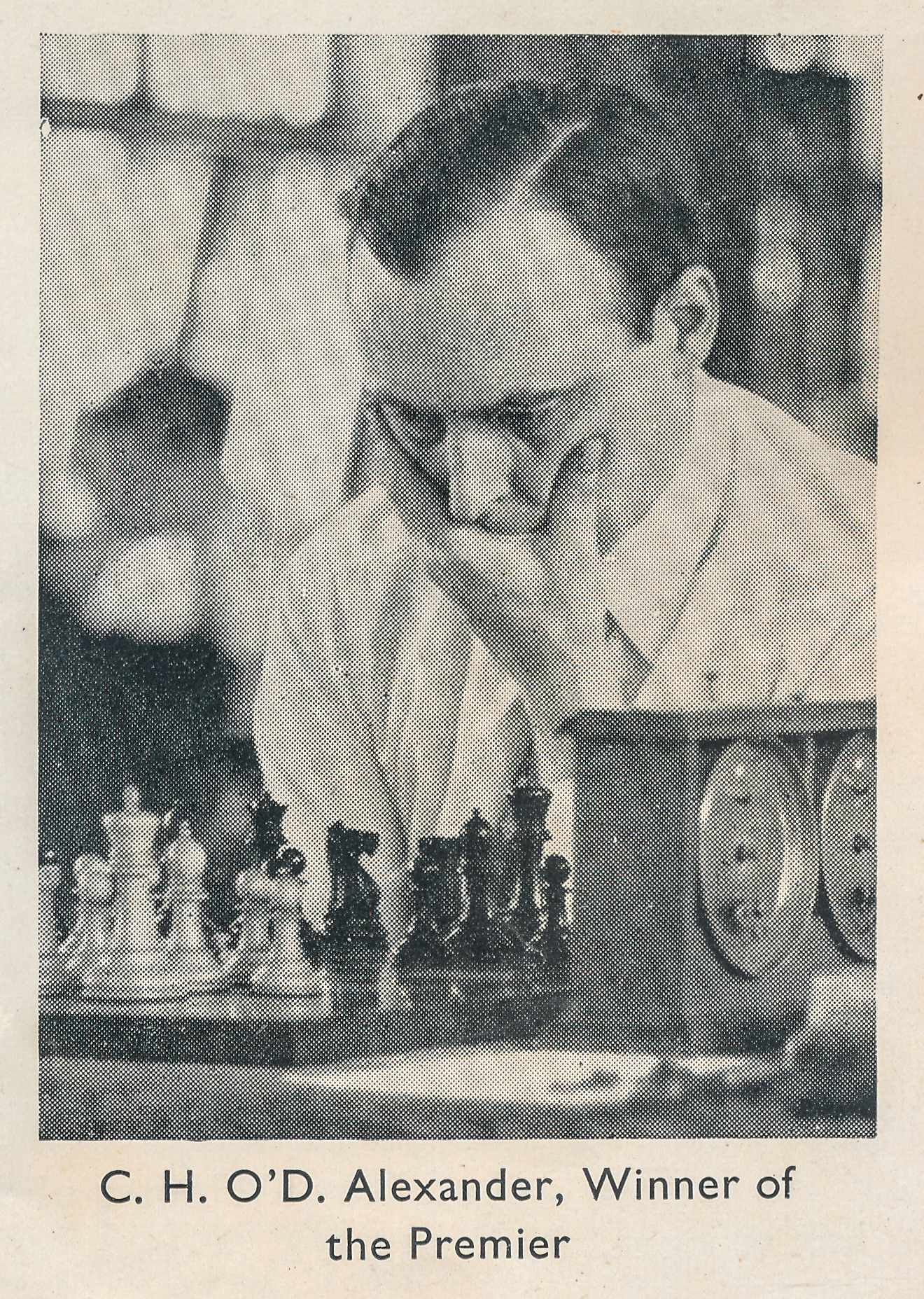

There were also tensions with BCF figures like Alexander and Golombek, in the latter case probably due to professional rivalry and Harry G’s identification with the BCM. Another prominent figure with whom BH crossed swords was the flamboyant Liverpool barrister Gerald Abrahams who threatened to sue over a report in CHESS of gambling debts incurred “on the turf’.

BH was no stranger to litigation. For example he had had a lawsuit with Jaques culminating in 1940 over the use of the term

“genuine Staunton-pattern sets” in his advertising. The case was initially lost, a potentially crippling blow, but then won on appeal with the aid of solicitor Julius Silverman (later a prominent Birmingham MP), Ritson Morry, Sir George Thomas and

other well-wishers. When Wood-Morry hostility was at its height in the early 1950s over pro- and anti-BCF views, BH drew attention in a letter to a Welsh chess organiser to Ritson’s short period in jail. The uncomplimentary term ‘gaolbird’ was used. A court case followed which the penurious Ritson, having been struck off as a solicitor could hardly afford, yet BH was cleared on the defence of justification. My fellow students and I at Birmingham University could only marvel at the daily press reports on the wrangles between two of our patrons whom we had feted at a celebratory dinner only a short while before.

Here is the point at which to mention BH’s support for chess in the universities. He was the long-time President of the

BUCA (British Universities’ Chess Association) and turned up at many of their events with support. He loaned equipment in the early days when not every chess club had sufficient clocks for a match – bear in mind that the austerity period in Britain lasted for years after 1945. BH also supported correspondence chess, being the founder of the Postal Chess League, a team event very popular in its day but now defunct.

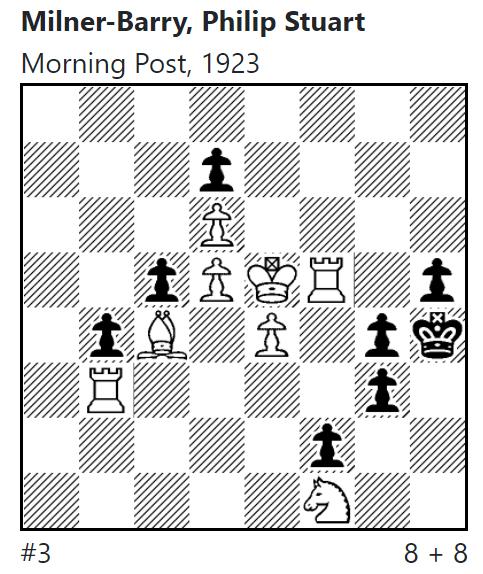

BH’s best playing performance was the British Championship of 1948 when he came second to Broadbent. The Midlander had actually started with 6.5 points from seven games, but the unsatisfactory position arose that he had to meet Broadbent in the last round when each had an adjourned game still to finish off.

The tension got to BH, he missed a clear winning chance against the Northerner and lost. Yet he should really have taken the title on the merits of the positions he had achieved. His rivals resented the fact that he had hired a second, namely Paul Schmidt, the Estonian player who was once thought of as almost as good as Keres in his native land. Schmidt had won the German Championship during the war in 1941. The British amateurs of 1948 were not impressed by this intrusion of professionalism and the importation of someone who carried the taint of possible Nazism. According to Brian Reilly, Gerald Abrahams was particularly scathing.

BH made a good impression on Botvinnik when the latter stayed at the Wood residence in Rectory Road, Sutton Coldfield, in 1967 (the reference for those who can read Russian is Baturinsky’s “…Tvorchestvo” trilogy on Botvinnik. The article was entitled: Albion shakhmatny i inoy. It appears on pp435 -448 of the third volume. A shortened version appears in English in Botvinnik’s autobiography Achieving the Aim). When I drew BH’s attention to the article and its peculiar title he responded with his usual erudite comment: ‘Albion? Yes, that’s the Roman reference to the white cliffs of Dover”. For most Brummies, “The Albion” did not mean a local pub, but rather the West Bromwich Albion football team!

In theory, the communist Botvinnik should have been distant from his host, the Midlands entrepreneur and business man, who drove him round to his engagements in Britain for three weeks, but their common love of chess triumphed over ideological

differences. In particular, the speed of production of CHESS, now on its own presses, was compared very favourably by the Soviet Patriarch to that of Shakhmaty v SSSR. British trade unions had a different view of course, in pre-Thatcher days, and BH had some tricky obstacles to overcome in this field. The Muscovite Botvinnik recorded the fact that the garage of BH’s large house was full of chess books (as were various rooms – to the abiding despair of Marjorie), so the family car was always parked outside on the drive. BH revealed to Botvinnik that he had not been able pay off his mortgage for decades due to the variable cash flow from his business and journalism.

BH was in love with study as a young man, he once told me, and he had a facility in various European languages, which made him always welcome abroad. Over the years, BH had a number of employees who were strong players, such as Brian Reilly, Owen Hindle and Robert Bellin, but none of them lasted long. Owen Hindle, a person of placid temperament, stuck it out the longest, but even he had his patience tried by the ‘boss’. One cannot hide the fact that BH was a controversial figure – perhaps the clue after all is that reference to his stubbornness and Yorkshire blood? I contributed to his magazine for many years, but certainly never wanted to work for him full-time!

I used to see BH in the last decade of his life only in the Hastings press room. For his age, he still took on a fantastic workload. Peter Clarke once commented that his father-in-law gave the impression of believing he would live for ever. Finally, Anno Domini told and BH sold his business to Robert Maxwell of Pergamon fame/notoriety in 1988.

In his final year, BH suffered from diabetes, and the resulting inability to walk meant he was confined to a wheelchair, but he still insisted on visiting Hastings one last time, where, in his prime, he had specialised in taking away Premier score sheets. Often they were taken not just to his hotel room, but even back to Sutton Coldfield, so hindering the work of other chess journalists unless Ritson or later, Peter Griffiths had got in first to create the bulletin.

What a character! We lack such a colourful figure nowadays. Where he still alive today, I imagine he would still be trying to put a bomb under the BCF.

Winter, Jaques and Wood

From Chess Explorations (Cadogan Chess, 1996) by Edward Winter we have further detail on the Jaques court case:

“Paul Timson, a lawyer, sends us reports on two legal cases connected with chess. In 1939 B.H.Wood found himself in the dock for having advertised for sale in CHESS in 1937 ‘genuine Staunton chessmen’. The plaintiffs were John Jaques & Son, Ltd. Sir George Thomas., Max Euwe and Lodewijk Prins appeared as witnesses for the defence. The case is referred to by Fred Wren in his article ‘Tales of a Woodpusher: Woodpusher’s Woodpile’, which appeared in Chess Review, 1949 and was reprinted in Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore. The issues of CHESS of the time also contained a huge amount of material on the case. The decision was that ‘Staunton’ alone was permissible description, but that the phrase ‘genuine Staunton’ implied a product made by Jaques & Son Ltd., as opposed to any Staunton pattern. However, B.H. Wood appealed and, in 1940, won.”

Other Sources

If you can get access then we recommend the eleven-page “B.H. Wood and his chess playing family” article in the August-2009 issue of Chess Monthly written by his son Chris Wood (helped by brother Frank).

Likewise The Chess Lawsuit of the Century is detailed in CHESS, volume 52, Number 1018, pp.392 – 394 by BHW himself.

Here is an obituary from the MCCU

Background information from Sutton Coldfield Chess Club

Barry Wood. A Personal Memory from Neil Blackburn (aka SimaginFan)

Alekhine’s Articles for CHESS by Michael Clapham

Here is his Wikipedia entry.

Download a pdf version of the 1st issue of CHESS