You might think I’m biased, but I’ve long thought that the most important people in any chess club are not the players, but the organisers. The secretary, treasurer and match captains who ensure everything runs smoothly.

All successful chess clubs have at least one: the loyal member who stays with the club for decades, through good times and bad times, while others come and go. Turning up for almost every match. Taking on any job that nobody else wants to do. One of those was the subject of this Minor Piece, James Richmond Cartledge.

The first ‘modern’ Richmond Chess Club (there were earlier organisations using the same name, but they weren’t involved in over the board competitive chess against other clubs) was founded in 1893, continuing until 1940 when, as a result of the Second World War, most clubs shut down for the duration and beyond. For most of that period, for over 40 years, James was a fixture at Richmond Chess Club, so much so that, when looking for a middle name, he chose the name of his chess club. Through the reports of the club AGMs in the Richmond Herald, now conveniently available online, we can trace his changing role in the club as well as the club’s changing fortunes. We can also listen into their discussions, sometimes on subjects which are still relevant today, a century or so later.

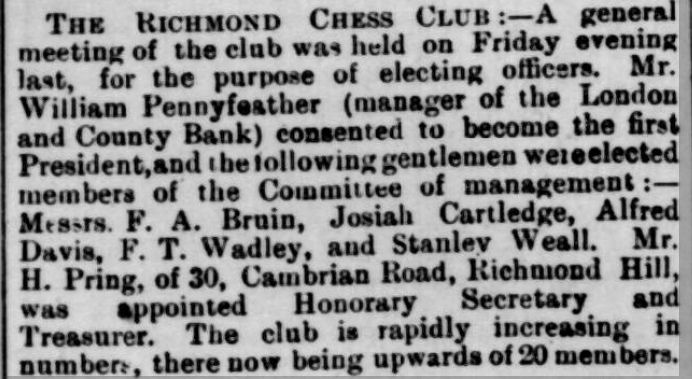

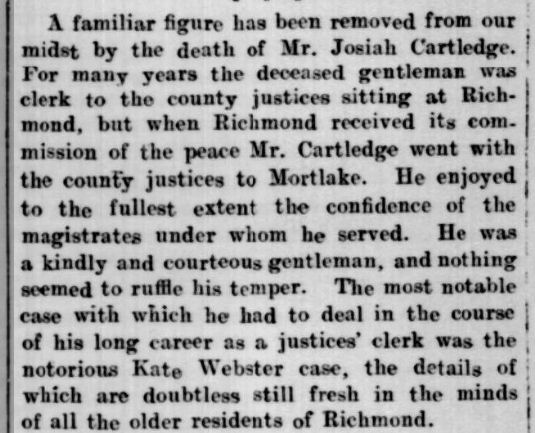

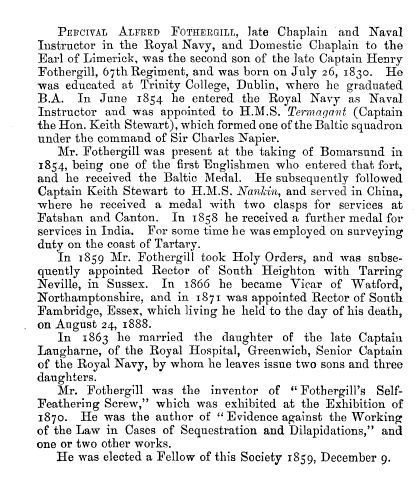

But first, we should meet his father, Josiah Cartledge, who was one of the club’s founder members.

Josiah was born in Camberwell, South London, in 1836, so he was now 57 years old. He married a cousin, Marian Frances Bruin, in 1858. (She doesn’t seem to be immediately related to Josiah’s fellow committee member Frederick Arthur Bruin.) A year later a son, Arthur, was born, but tragically Marian died, probably either in or as a result of childbirth.

It wasn’t until ten years later that Josiah married again. His second wife was Frances Victoria Wastie, and their marriage would be blessed by three children, William (1870), Adeline Frances (1872) and James (1874). Josiah and Frances were both chess enthusiasts, competing to solve the problem in their newspaper of choice, the Morning Post, with young Arthur sometimes joining in.

Josiah was a legal clerk, a highly responsible job, and, round about 1873, he became Clerk of the Richmond Petty Sessions, moving out from South London. The 1881 census found the family at 5 Townshend Villas, Richmond, and they were still there in 1891, when his job had expanded: he was also Clerk to the Lunatic Asylum. William was helping him out, while 17 year old James, choosing a different career path, was an architect’s pupil.

It was no surprise then, that, when Richmond Chess Club started up in Autumn 1893, Josiah was one of the first through the door, and, given his status in society, he was a natural choice for the committee.

And here he is, from an online family tree.

Young James was now taking a serious interest in chess and it wasn’t long before his father brought him along to join in.

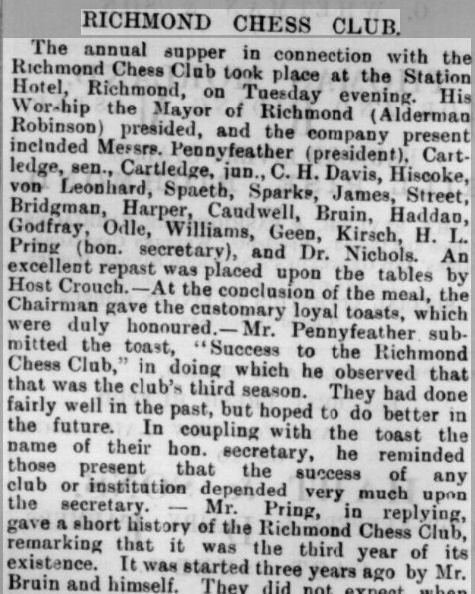

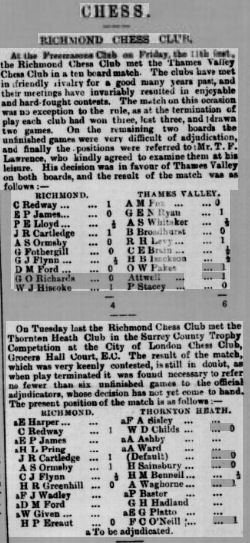

Here they are at the Annual Supper in 1896.

Before you ask, the Mr James there was no relation to me: it would be a few more years before I joined.

(Edwin Peed James (1853-1933) was a solicitor who hit financial problems, and, after being declared bankrupt, became a commercial traveller.)

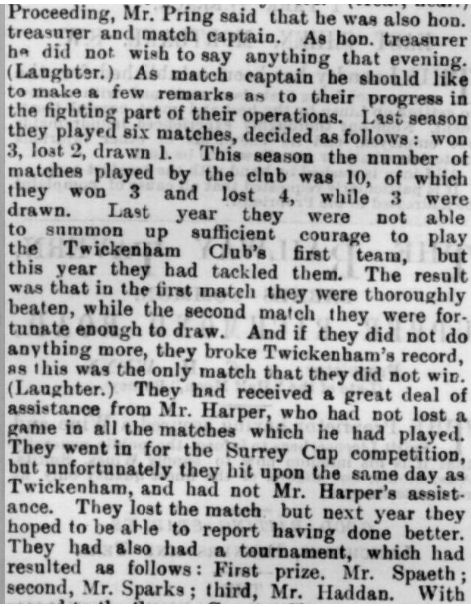

Horace Lyddon Pring (1870-1938), a solicitor’s clerk working in accounts, was a young man with boundless energy and ambition. He was not only the club secretary, but treasurer and match captain as well. He reported that the club now had 45 members, 11 of whom were new, but they’d also lost a few. “One or two of the younger members had become mated so effectually – (laughter) – that they could not get out.” They had also moved to a new venue, having “started in a baker’s shop, but that got too hot for them. (Laughter).” Mr Pring also had a sense of humour.

From later in the report:

You’ll see that they’d attracted at least one strong player in Thomas Etheridge Harper.

At the end of the supper, toasts were drunk to the accompaniment of music. Songs (the popular music-hall ditties and parlour ballads of the time) were sung and the Kew Glee Singers contributed a selection of glees. Musical entertainments of this nature would continue to be a feature of Richmond Chess Club’s social events for many years to come.

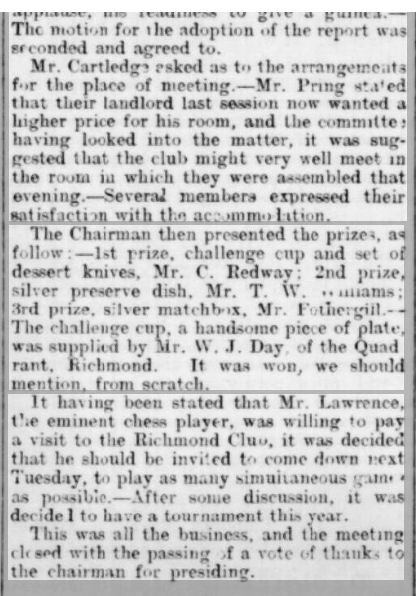

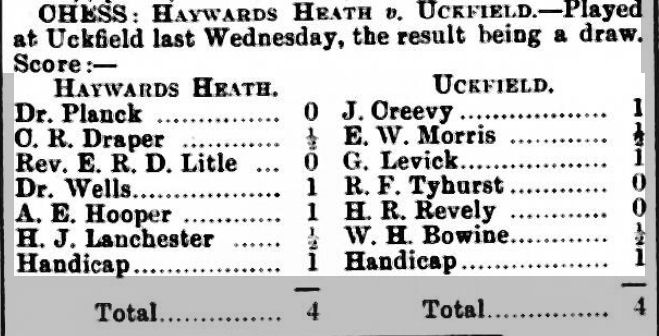

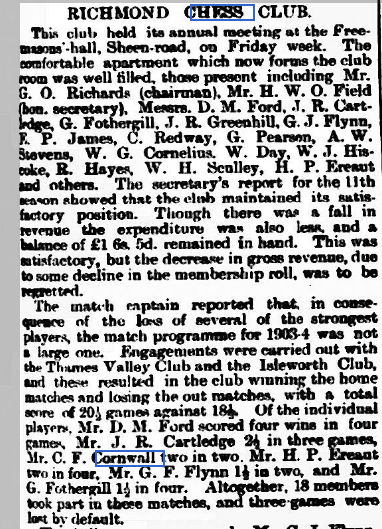

An extract from the 1898 AGM shows the club making progress in several ways.

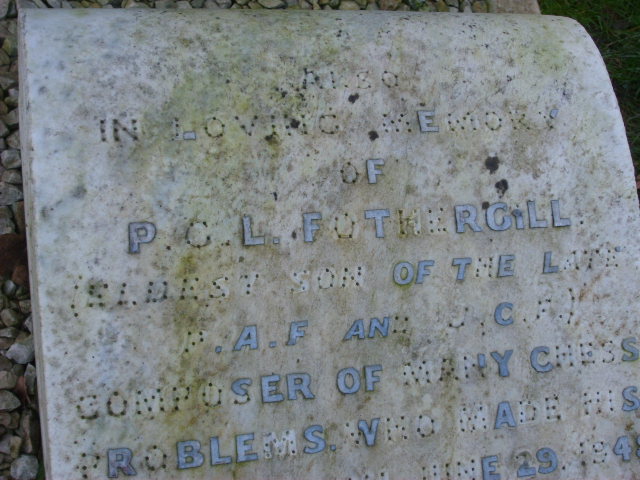

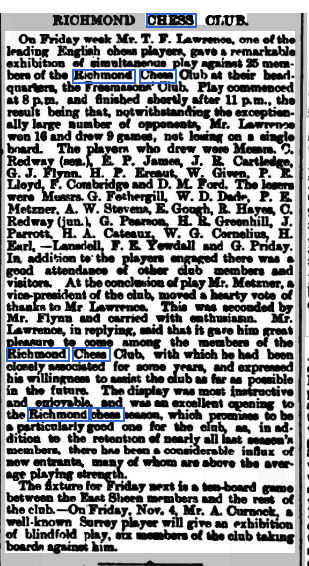

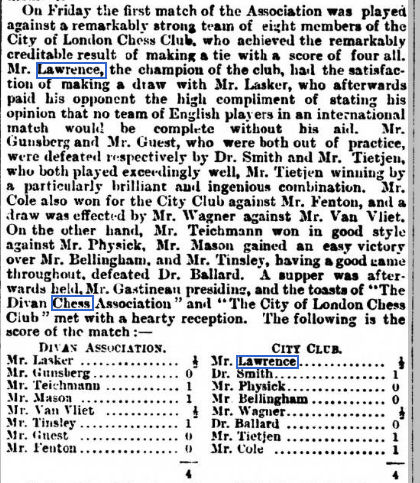

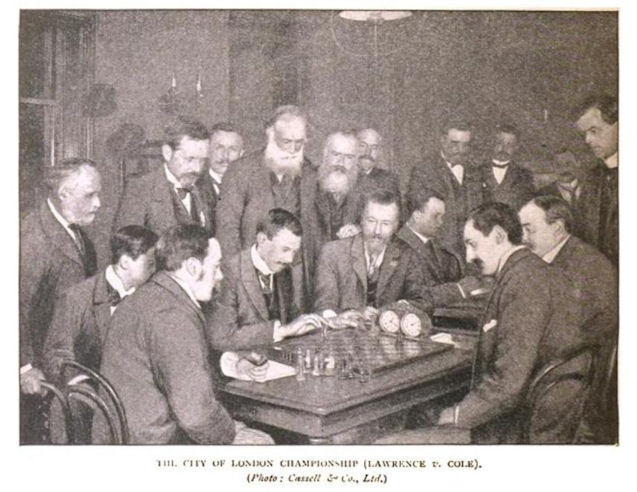

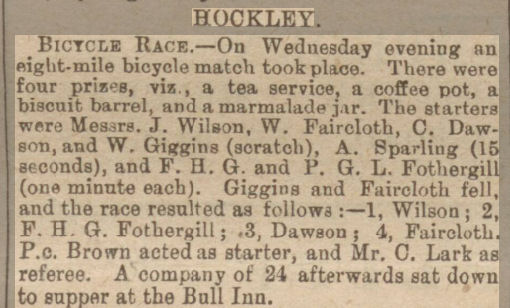

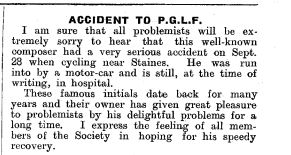

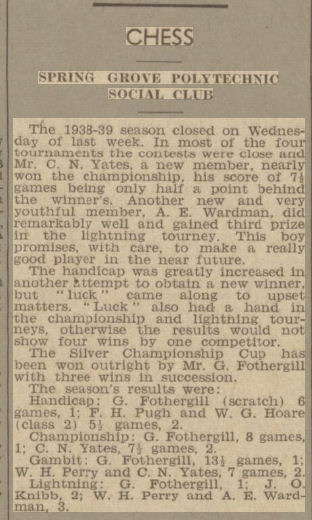

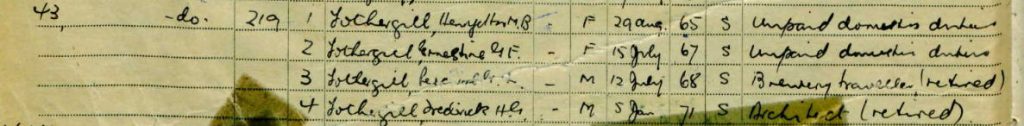

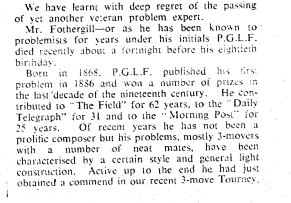

They had to move venues when their landlord put the fees up: still a familiar story for many chess clubs today. Nevertheless, the club was now attracting strong players such as our old friends Charles Redway and Guy Fothergill, and had arranged a visit from one of London’s leading players, Thomas Francis Lawrence. His annual simuls would become a club tradition lasting many years.

There were some exciting prizes for the lucky – or skillful – winners: dessert knives, a preserve dish and a matchbox.

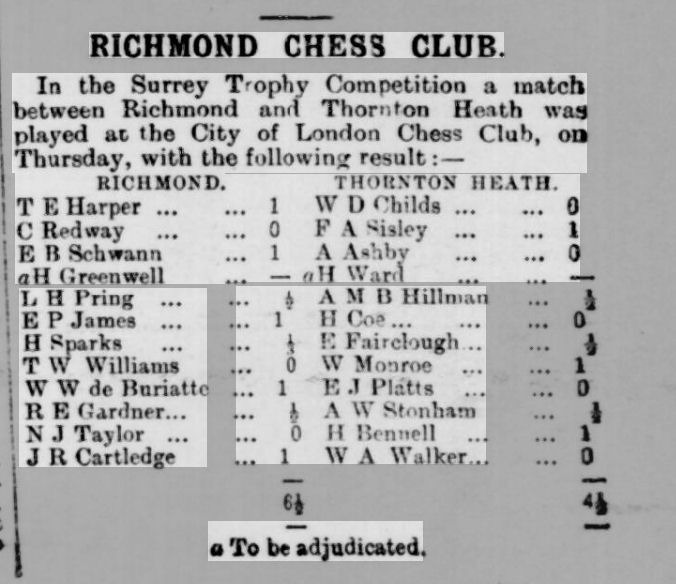

Josiah was more of a social player, but James had a lot more ambition. By 1900 he was starting to play in competitions such as the Surrey Trophy, albeit on bottom board.

He had also acquired a middle name (he was just James at birth), possibly to avoid confusion with his father. Did he choose Richmond in honour of his home town, or of his chess club?

Here he is, then, winning his game against Thornton Heath. which, as often happened in those days, took place in central London rather than at either club.. Richmond had won the Beaumont Cup in its second season, 1896-97, but by now were trying their hand against the big boys, successfully in this case. The Surrey Trophy and the Beaumont Cup, then, as now, were Divisions 1 and 2 of the Surrey Chess League. Some things never change.

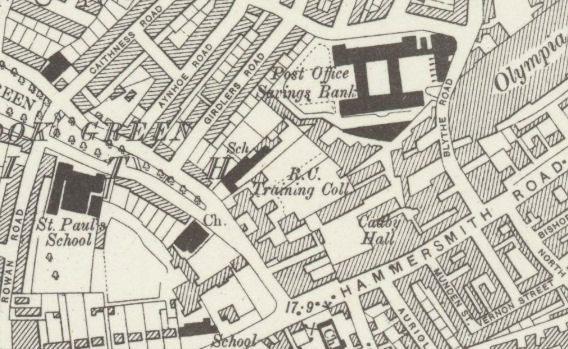

By 1901 Josiah’s job had moved to Mortlake while James had a new job as Assistant Surveyor for the Urban District of Barnes The family had moved to Milton House near Mortlake Station, probably somewhere on Sheen Lane near the junctions with Milton Road and St Leonard’s Road today: a location which would have also been handier if you were in the business of surveying nearby Barnes. Adeline and James were still at home with their parents, along with a cook and a housemaid.

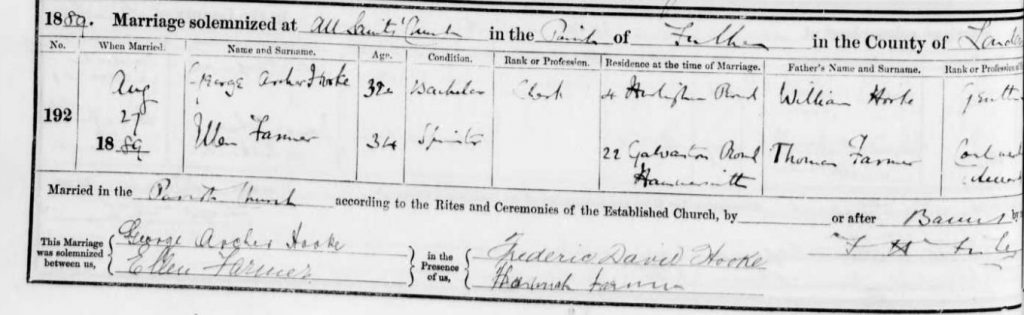

By 1904 the club was in something of a slump, having lost a number of strong players they had withdrawn from the Surrey competitions and were only playing friendly matches along with their internal competitions. Both Josiah and James were very much involved, even though James had married Gertrude Francis (sic: it was her mother’s maiden name) Griffiths at Christ Church East Sheen the previous year. Sadly, it was to be Josiah’s last year.

If you’re interested in the notorious Kate Webster case, as I’m sure you are, Wikipedia deals with it here.

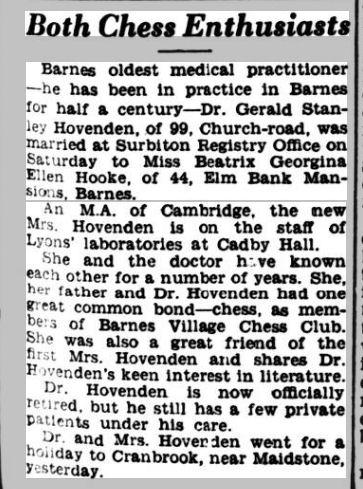

James and Gertrude went on to have three children, Raymond Francis (1905), Hilary Frances (1907) and Kathleen Vivian, known by her middle name (1911), but his new responsibilities as a husband and father didn’t stop his involvement with Richmond Chess Club. Although he had been mated, Gertrude still let him out.

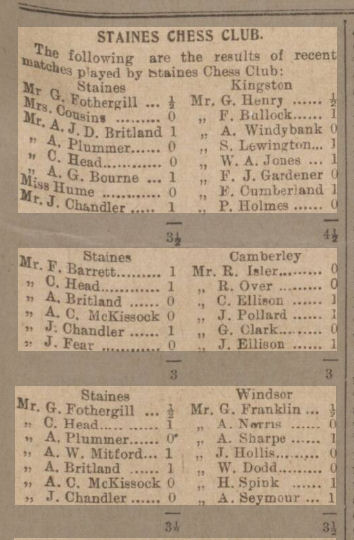

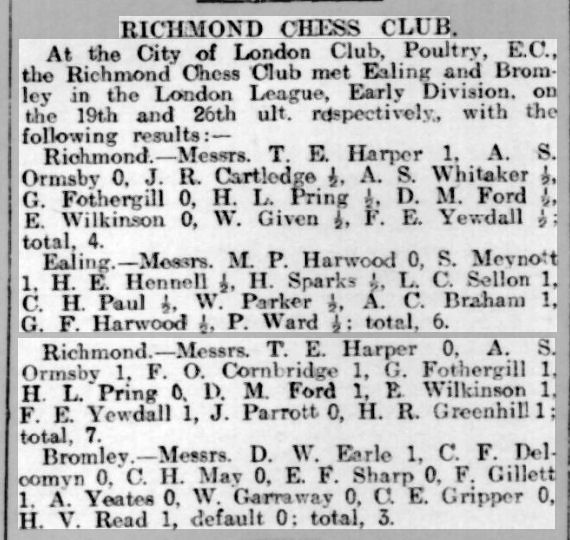

1904 saw some of the club’s stronger players returning, and they were tempted to re-enter the Surrey Trophy. The following year’s AGM would announce that their membership had increased from 24 to 44 within the space of two years. James Cartledge must have been improving fast, as he was now playing on a much higher board.

Six adjudications in a 12 board match seems a bit unsatisfactory, but this situation would be common for many decades to come. You might consider any competition not decided on the night rather bizarre, but adjudications still happen occasionally in the Surrey League today.

At the 1909 AGM, James Richmond Cartledge was elected to the post of Treasurer, “it being remarked that that gentleman had served the club in the capacity of match captain and secretary”.

By the 1911 census the family were living in 10 Palewell Park, East Sheen, just off the South Circular Road. Baby Vivian had arrived a few days earlier, but had not yet been given a name. It was a crowded house, with James, Gertrude and their three young children, James’s sister Adeline, working as a day governess for another family, Gertrude’s sisters Helena and Annie, along with a monthly nurse to look after the baby and a domestic servant.

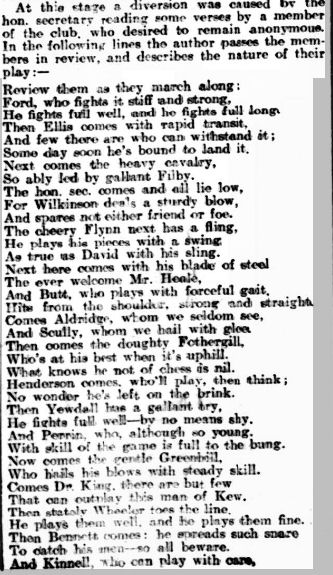

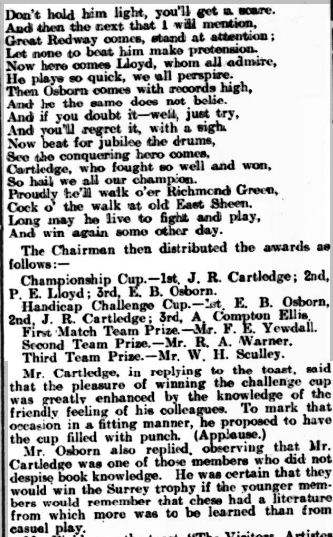

After the 1911 Richmond Chess Club AGM, hilarity ensued when, during the toasts, the Hon Secretary read out some verses composed by an anonymous member, describing some of the club’s members.

A few days later, another verse appeared: it’s not clear whether or not this was written by the same poet.

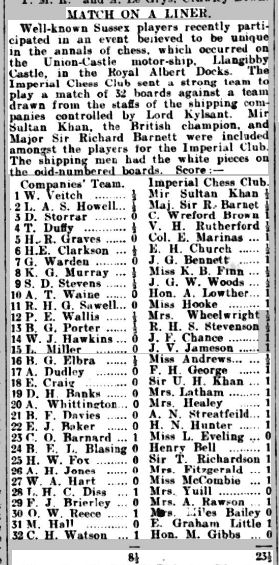

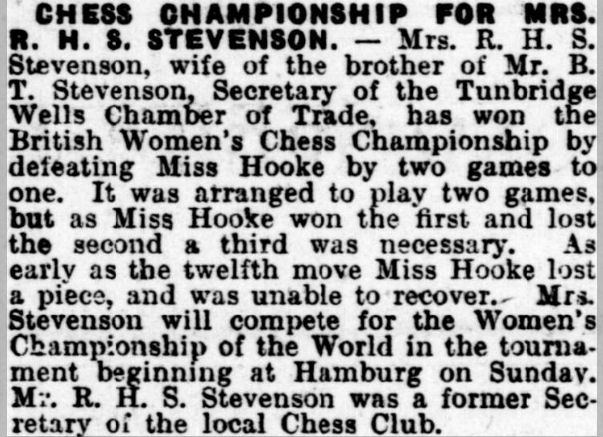

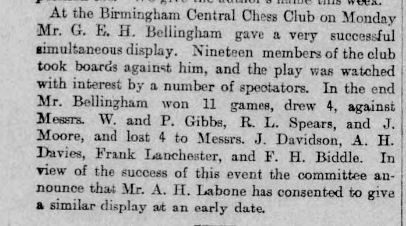

For several years the committee had been discussing the idea of inviting the British Chess Federation to hold their annual championships in Richmond, and that duly came to pass in 1912. Although the event was very successful, there were very few club members taking part. I’ll perhaps look more at the tournament in a future series of Minor Pieces.

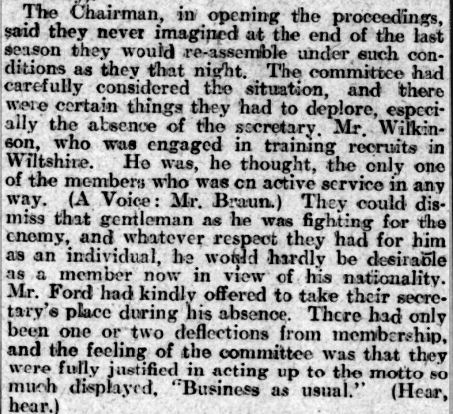

Then, in 1914, war broke out. At their AGM the club decided that it was ‘business as usual’, although they had to appoint a new secretary, and their German member, who was fighting for the enemy, was no longer welcome.

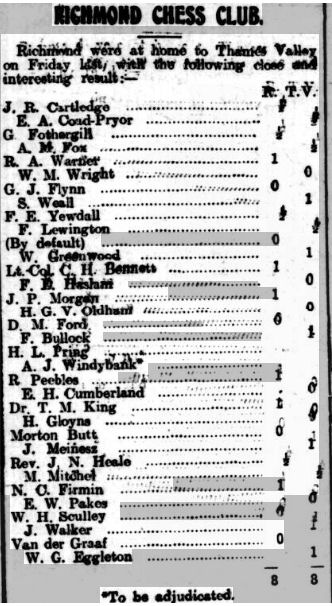

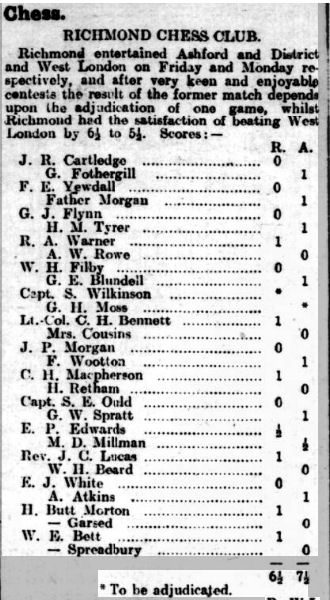

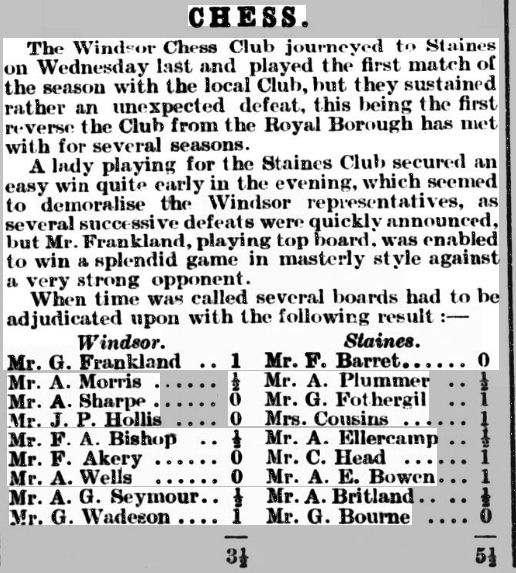

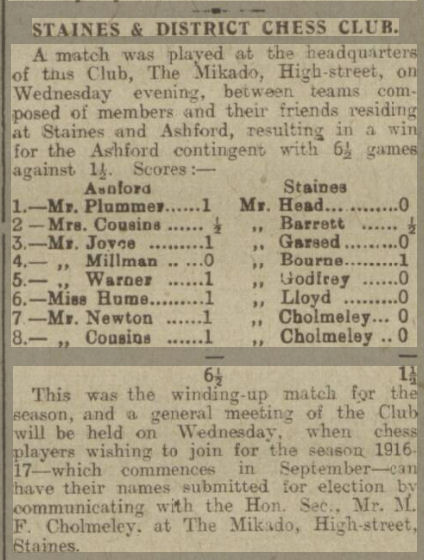

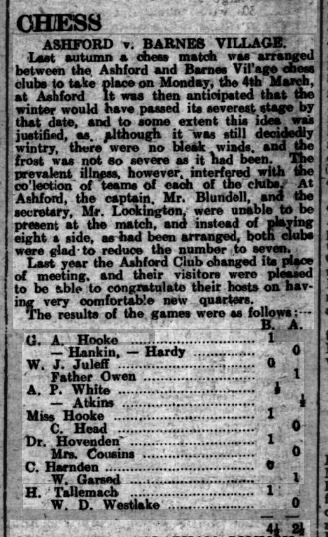

There was less opportunity for competitive chess: the Surrey Trophy and Beaumont Cup ran in 1914-15, only the Surrey Trophy was contested in 1915-16, and then the league went into abeyance until the 1919-20 season. Friendly matches continued, though, as in this match between Richmond and their local rivals, which saw Cartledge facing an interesting opponent in Eric Augustus Coad-Pryor.

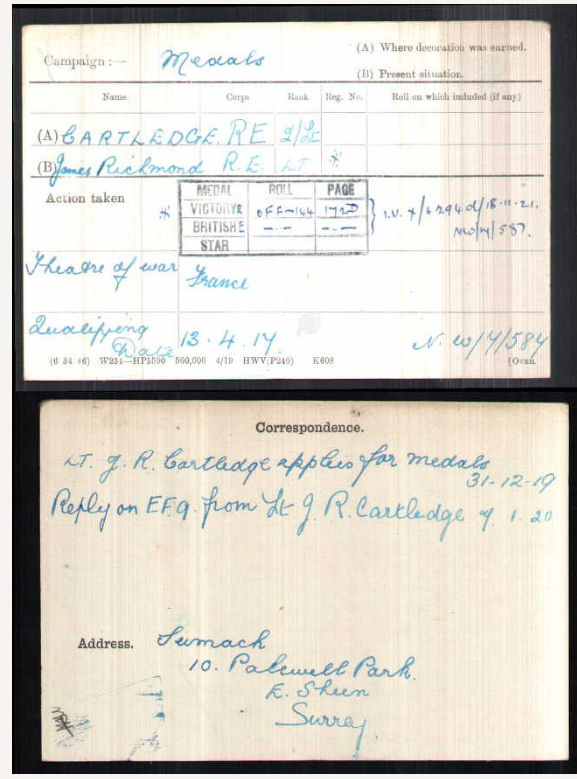

Although he was now in his 40s, James Richmond Cartledge was still ready to serve his country, and, with his knowledge of engineering, he signed up as a reservist for the Royal Engineers.

The 1917 AGM reported that he had been called up and was in France in the thick of the fighting.

Here he is, on New Years Eve 1919, applying for his Victory Medal.

Back from the war, James returned to his duties at the club with whom he shared a name, now taking the chair at their AGMs.

The 1921 census found him back at 10 Palewell Park, and again working as an Assistant Surveyor and Civil Engineer in the Local Government Service, employed by the Urban District of Barnes. His wife and children were all at home, and they in turn employed a domestic servant.

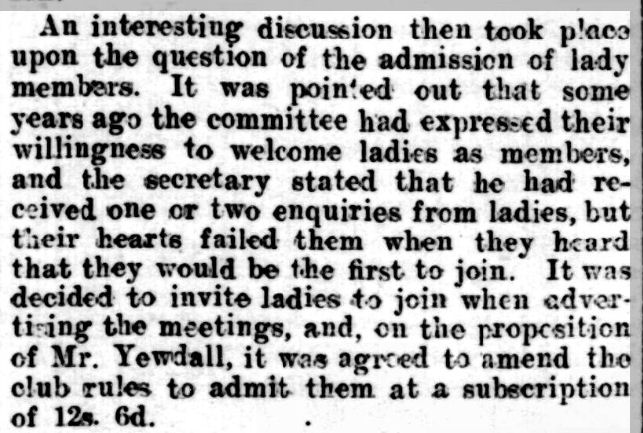

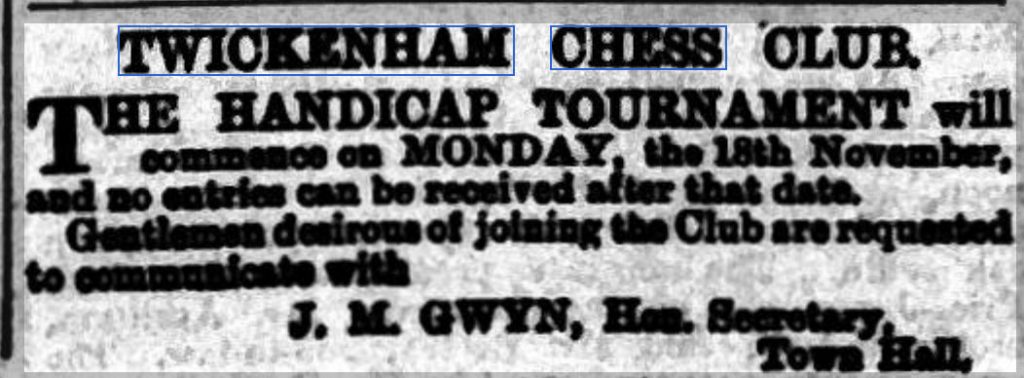

The 1921 AGM revealed that new clubs had started at Twickenham, Teddington and Barnes. There was also a discussion about how to attract more lady members: it was agreed to offer them a 5 shilling discount on their membership.

If they’d been looking for a new venue, they could have considered the Red Cow Hotel, Sheen Road, Richmond, which, on the same page, was advertising a Large Club Room for hire. Forty years or so later, their offer would be taken up by what was then the Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club.

The following year, the Hon. Secretary, Captain Wilkinson, reported that ‘the club had two lady members. He lent one of them a book on chess and he had neither seen nor heard of her since. He did think, however that chess was a game that women should take up’.

In 1923 the Club Dinner was revived, not having taken place since 1914. The format was very much the same as before, with speeches, prizegivings and musical entertainment provided by Miss Edythe Florence (contralto), Miss Florence (pianist), Mr. M. J. O’Brien (tenor) and Mr. Len Williams (humorist).

The club’s fortunes waxed and waned over the years, and by 1926, with seemingly little interest in chess in Richmond, and successful new clubs in Barnes and Twickenham proving more attractive for residents of those boroughs, questions were asked about the future.

In 1926 Captain Wilkinson decided to stand down for a younger man.

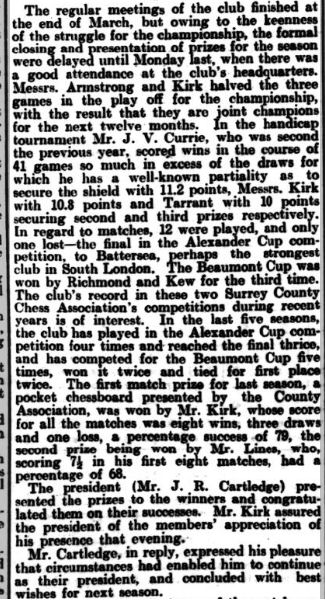

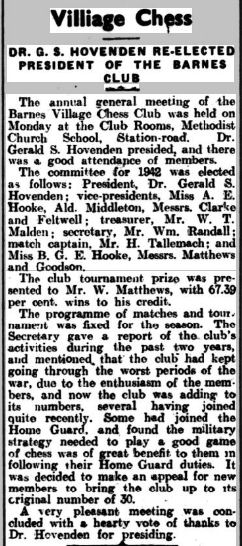

That younger and more energetic person turned out to be new member Wilfred Hugh Miller Kirk, not exactly a young man himself, but with an outstanding record in chess administration within the Civil Service. By the 1929 AGM, things were looking up. Kirk reported that the club had had their most successful season for several years, winning 12 of their 18 matches. Most importantly, although not mentioned in the newspaper report, a decision had been made to merge with Kew Chess Club. They now became Richmond & Kew Chess Club, acquiring new members, including Ronald George Armstrong, a player of similar strength to Kirk, and a new venue enabling them to resume meeting twice a week: once in Richmond and once in Kew. Having an enthusiastic and efficient club secretary makes a big difference. James Richmond Cartledge would still have been very much involved, his experience invaluable in the decision making process.

(Ronald George Armstrong (1893-1952), the son of a Scottish father and French mother, was, unusually for the time, but like Wilfred Kirk, a divorcee. His job involved selling calculating machines. He was clearly a strong player, but didn’t take part in external tournaments.)

In 1930 there was sad news for James as his wife Gertrude died in hospital at the age of 55, but his bereavement didn’t put an end to his chess activities.

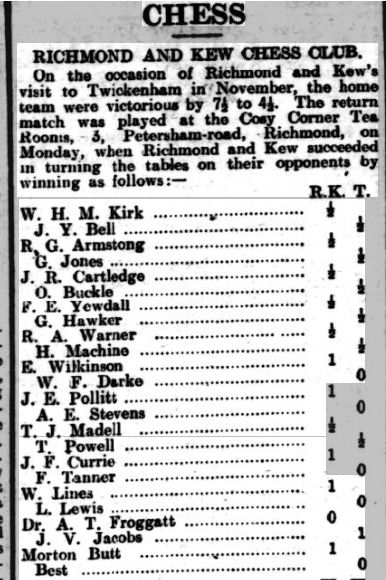

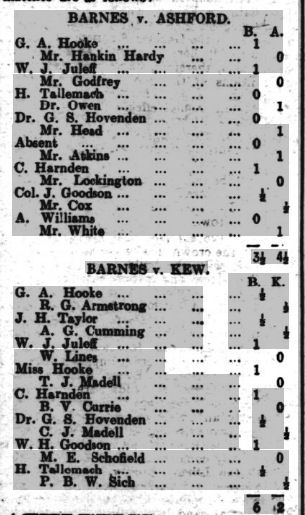

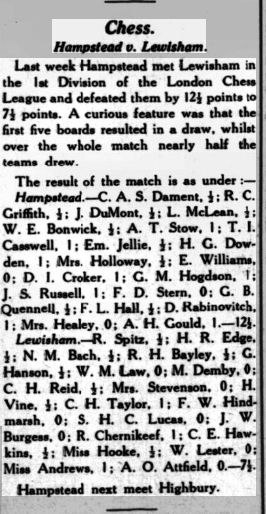

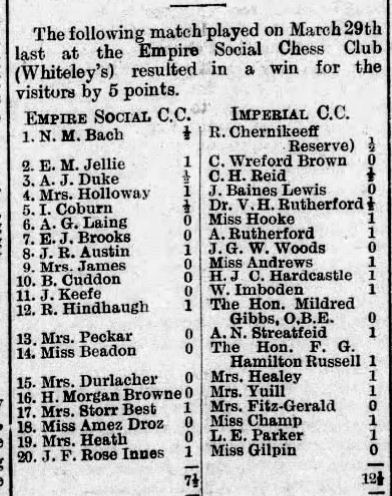

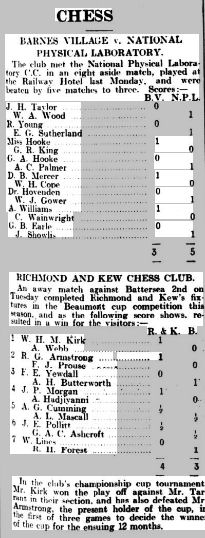

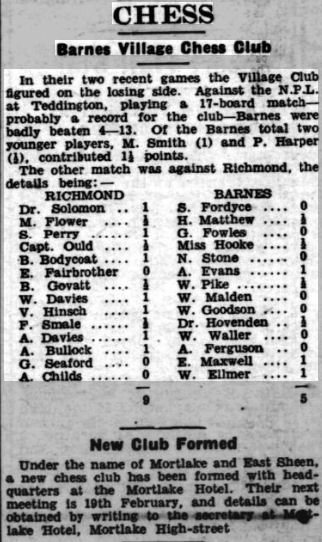

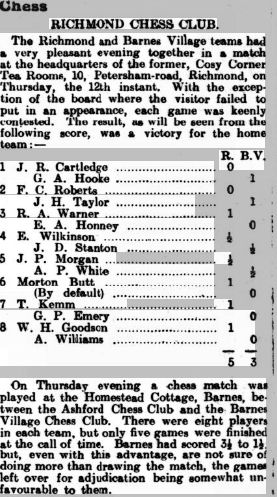

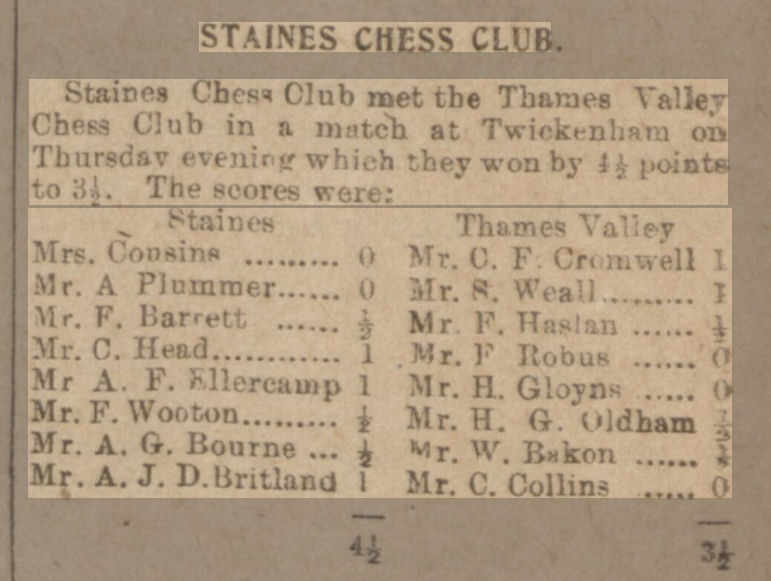

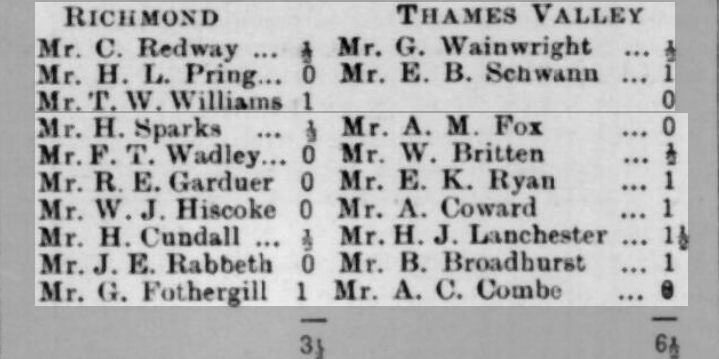

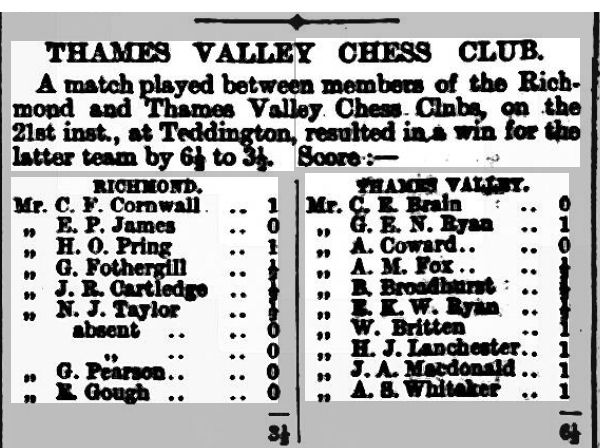

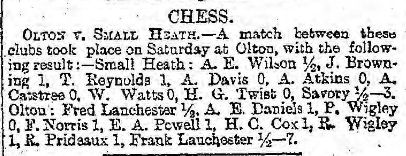

By this time Kirk and Armstrong were disputing the top two boards, with Cartledge on board 3, as in this match against their local rivals.

While the Twickenham team lacked big names, their top boards must have been reasonable players. James Young Bell continued playing well into the 1960s: in 1965, in his late 80s, he played a board below the young John Nunn in a match between Surrey and Middlesex. At this time he was a next door neighbour of Wallace Britten in Strawberry Hill Road, thus providing a link between the two Twickenham Chess Clubs.

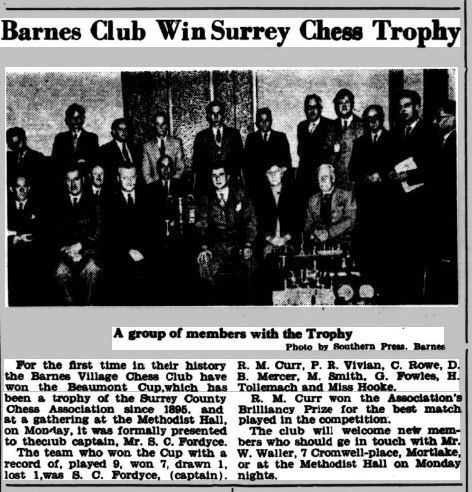

In that season, the newly amalgamated club won the Beaumont Cup for the first time since the 1896-7 season, As Wilfred Kirk explained at the AGM, ‘union is strength’. The following season they finished equal first with Clapham Common, but lost the play-off match.

Although they were successful over the board, membership numbers were still modest. The 1933 AGM reported only 24 members. By now James Richmond Cartledge had risen to the post of President, but asked the club not to nominate him again as he was retiring from business and planning to move away from the area. He was persuaded to agree to remain President until he moved, but in fact that would be further away than he expected. It appears he moved to Ham on his retirement, close enough to continue his membership.

In 1934 they were able to report that they had won the Beaumont Cup for the third time, but lost to Battersea in the final of the Alexander Cup.

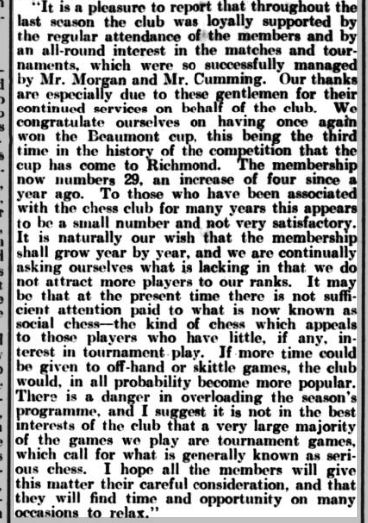

The 1934 AGM brought up the important topic of social chess, the secretary’s report suggesting that the club should offer more time for casual games rather than too many tournament and match games. This discussion is still very relevant in all chess clubs today.

The Hon Secretary at the time was Francis Edward Yewdall (1875-1958), one of the club’s stronger players, who, coincidentally or not, had the same job as Cartledge in the neighbouring borough: he was the Assistant Surveyor for the Borough of Richmond.

The last mention we have for James Richmond Cartledge at Richmond & Kew Chess Club is in October 1938, so presumably it was soon after that date that he moved away.

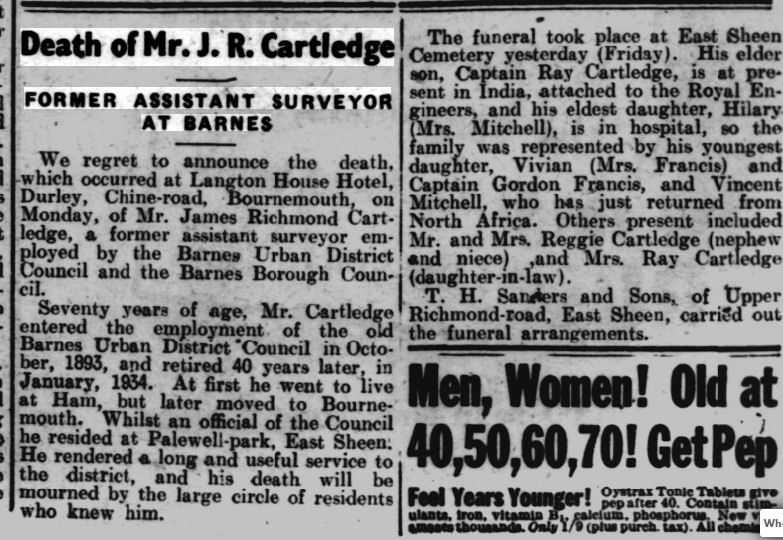

By the time of the 1939 Register he hadn’t gone far. He was staying in the Mountcoombe Hotel in Surbiton, which, coincidentally, had also been the residence of chess problemist Edith Baird back in 1911. He then moved to the south coast: not, like many chess players, to Hastings, but to Bournemouth, where he died in 1943.

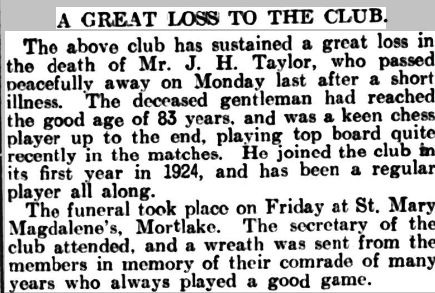

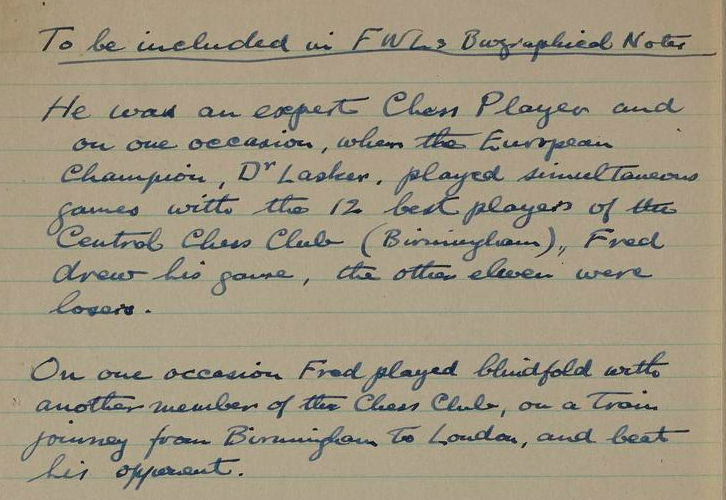

Yes, he rendered a long and useful service to the district, but the obituary failed to mention his long and useful service to Richmond (& Kew) Chess Club over a period of almost 40 years, serving at various times as secretary, treasurer, match captain, chairman and president. Although not of master standard, he was a strong club player (I’d guess about 2100 strength) as well. The likes of him, organisers and loyal club supporters, are just as important to the world of chess as grandmasters and champions. In his day it was the habit to drink toasts at club dinners: join me today in drinking a toast to James Richmond Cartledge.

Sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

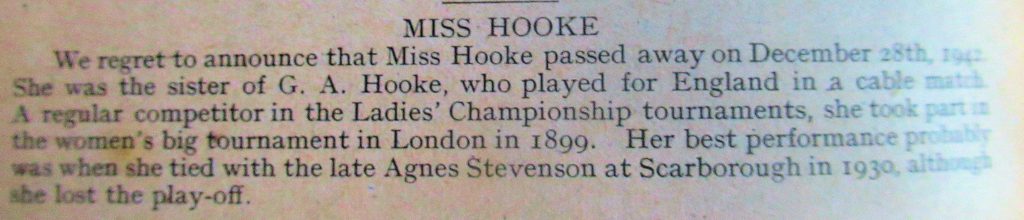

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

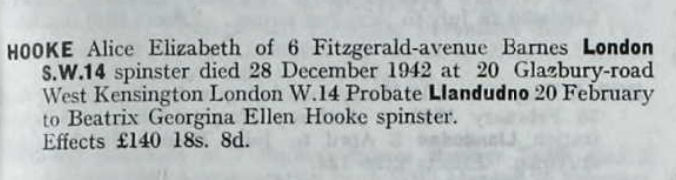

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.