We remember FM Stephen H Berry who passed away, this day, January 4th 2019.

Stephen was born on Sunday, March 18th 1951.

He played for Wimbledon in the London League.

Here is his ECF rating record.

Obituary from Andrew Stone

We remember FM Stephen H Berry who passed away, this day, January 4th 2019.

Stephen was born on Sunday, March 18th 1951.

He played for Wimbledon in the London League.

Here is his ECF rating record.

Obituary from Andrew Stone

Last time I left you in 1980, when Mike Fox had moved to Birmingham, leaving me in charge of Richmond Junior Club, whose membership included a growing number of very strong and talented young players, inspired by Mike’s teaching and charismatic personality to excel at chess.

I had been the backroom worker to Mike’s front man, but now, reluctantly, I was the front man as well.

My forte was organising rather than teaching, and, wanting to provide experience of serious competitive chess, I ran regular training tournaments for our strongest players.

Here, for instance, is a game from a 1981 training tournament. Aaron Summerscale is now a grandmaster and chess teacher. Nick von Schlippe is now an actor, director and writer, but maintains his interest in chess. Nick was one of a quartet of outstanding players from Colet Court/St Paul’s along with Harry Dixon (now playing chess in South East London), Michael Arundale and Michael Ross.

Click on any move of any game in this article for a pop-up window.

To give you some idea of our strength four decades ago, the leading scores in the 1982 Richmond U14 Championship were:

Nick von Schlippe 5/6

Demetrios Agnos (now a GM) 4½/6

Michael Ross 4/6

Philip Hughes 3½/5

Gavin Wall (now an IM and, for many years Richmond London League captain), Ben Beake, Harry Dixon, Sampson Low (currently secretary of Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club) 3½/6

Ali Mortazavi (now an IM) 3/5

Mark Josse (now a CM), Rajeev Thacker 3/6

and 6 other players, including Chris Briscoe (now a CM).

Here’s a game from that event for your enjoyment.

The results of our 1983 Under 14 Championship told a fairly similar story.

Scores out of games played (there are either two missing scoresheets or two players took byes in Round 4 and two didn’t play in Round 6) were:

Gavin Wall 6/6

Demetrios Agnos 4½/6

Philip Hughes 4/6

Harry Dixon, Ben Beake, Chris Briscoe 3½/6

Aaron Summerscale 3/5

Michael Ross, James Cavendish, Rajeev Thacker, Mark Josse, Bertie Barlow 3/6

Ali Mortazavi 2½/5

Leslie Faizi 2½/6

Grant Woodhams 2/6

Alan Philips, Chris Bynoe 1/5

Daniel Falush 0/6

At some point I’d acquired a copy of Chess Life and discovered that the members of our small suburban junior chess club were, over the top few boards and applying the conversion factor in use at the time, stronger than the juniors in the whole of the USA.

The significant factor in all this is, for me, not just the strength of the players, but how many are still playing, or at least keeping up with the chess world, and, even more so, how many I’m still in touch with, or have spoken to on social media, almost 40 years on. Talking to them now, they always have very fond memories of their time at Richmond Junior Club.

What we were doing, although I wasn’t aware of it then, was building a lifelong chess community. Producing future GMs and IMs was merely a by-product of the actual purpose.

But it was clear that, as the younger players coming into the club were less strong and less interested than their predecessors, changes had to be made. Perhaps I needed someone who was a much better chess teacher than me and, like Mike Fox, had the charisma to attract strong new members into the club. There was no doubt who the best chess teacher was in my part of the world: Mike Basman. He agreed to help and, for a time in 1983-84 we worked together.

Of course, Mike was, and still is, brilliant, but he’s also a maverick, someone who, like me, prefers to do things in his own way. There were a couple of issues, in particular, where we disagreed.

Mike has always been known for his love of eccentric openings, and he’d sometimes give lessons on these. My view was different: children should, in the first instance, be given a thorough grounding in all the major openings. If they decide later that they want to experiment, that’s fine, but understand the basics first.

My second point was that we were inviting near beginners to training tournaments where clocks and scoresheets were used. My view was, and still is, that children should be able to play a reasonably proficient game without giving away pieces before clocks and scoresheets are used. Clocks and scoresheets add to the game’s already bewildering complexity and, if children are not used to them, they will concentrate too much on remembering to press their clock and working out how to write their moves down and forget about how to play good chess.

This is still one of my big problems with junior chess today: we’re putting children who barely know how the pieces move into tournaments with all the accoutrements of proper grown-up chess: clocks, arbiters, strictly observed silence, touch and move. My view is that this is totally wrong, but, even more so today than 40 years ago, I appear to be in a small minority. Very often, these days, parents are insisting that their children should take part in serious external competitions before they’re ready in terms of both chess and emotional development.

You’ll find out next time how I addressed these two issues over the following years. I had to find my own methods of doing exactly what I wanted. If anyone else wanted to come in with me, that was fine, but I was never going to compromise on doing it someone else’s way rather than mine.

Meanwhile, in April 1984 we were offered the chance of a simul given by Hungarian GM Zoltan Ribli, who at that time was ranked 13th in the world with a rating of 2610. Although we had to pay quite a lot for the privilege, this was too good an offer to turn down. According to the scoresheets that were handed in he scored +13 =4 -2: again, a pretty good performance for a suburban junior chess club! Here’s one of his losses.

At that time, we were constitutionally part of Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club, and our accounts were incorporated in theirs. Up to that point we’d made a reasonably healthy profit each year, but in 1983-84 we had only just broken even. At the 1984 AGM the RTCC treasurer wasn’t impressed, thinking we might jeopardise the club’s finances in future, and uttering the immortal words ‘What’s a Ribli Simul?’. (Strangely enough, the other day I chanced upon a record of him playing in a simul some 35 years or so earlier!)

Our turnover was also much larger than that of RTCC so it seemed sensible that we should declare financial independence. I would remain on the committee as the officer responsible for junior chess, providing a link to RJCC. (I still hold that post today, but without the RJCC link.) We already had a parent, Derek Beake, serving as our Treasurer, a role he’d occupy for 22 years, long after his son Ben had given up competitive play.

In 1985 we were again offered the chance of a simul given by a world class player, in this case by local GM John Nunn, who, at the time, was ranked joint 11th in the world (one place behind Ribli) with a rating of 2600. This time we invited a few of our friends from Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club to join us.

Out of 23 games, John scored 14 wins, 6 draws and 3 losses, to RTCC’s Paul Johnstone, a slightly pre-RJCC Richmond Junior (someone suggested the other day I should write something about the pre-RJCC Richmond Juniors, which perhaps I should), to future GM Demetrios Agnos and to the unheralded Leslie Faizi, who had also drawn with Ribli the year before.

Even our lesser lights from that generation could play pretty good chess. Here’s a draw against Alan Phillips, who had beaten Ribli the year before (and who contacted me on Twitter a few years ago).

Yes, many of our stronger players from a few years earlier still kept their association with the club, and with chess in Richmond in general (and some of them still keep that association in the 2020s), although they had now outgrown our Saturday morning sessions. We were also no longer successful in attracting strong players into the club. (I suspect, looking back, they just weren’t around in our area: these things come and go.)

I knew I needed to make changes, and that I had to find my own way of running the club rather than trying to work with anyone else.

I wanted to separate the club in order to differentiate between the players who were able to play a proficient game, and who needed experience playing under more serious conditions using clocks and scoresheets, and those younger and less experienced players who were not yet able to play fluently without making regular oversights.

By now home PCs had become available. I was able to use my (admittedly limited) programming skills to write a grading program in BASIC for my BBC Micro into which I entered all our internal club results. I used a pseudo-BCF system with a crude but reasonably effective iterative process providing anti-deflation factor which would take into account my assumption that our members were either improving or remaining stationary at any point.

This gave me the information to decide, by monitoring all the internal results of all our members, which players should be in which group. The decision was made – and my intuition again turned out to be correct (although it’s not how things work today) – that players of primary school age would move up to the higher group when they reached a grade of 50 (equivalent to 1000 Elo). I’ll write a lot more about this, either here or elsewhere, later.

By the start of the 1986-87 season the club had become something totally different. Two things had also happened which would have an enormous impact on the club’s further development.

You’ll find out what they were, and a lot more besides next time.

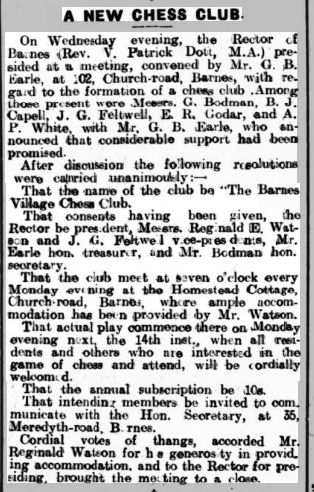

In January 1924 there was some big news for chess players in the Richmond area. A new chess club, the Barnes Village Chess Club, was to be formed.

None of the names at this meeting are familiar, but they soon started playing matches against other local clubs.

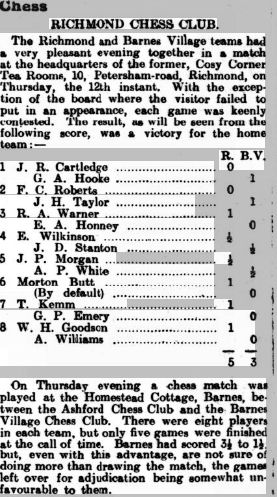

Here they are a year or so later, visiting their Richmond neighbours at the charming Cosy Corner Tea Rooms, as well as entertaining Ashford, who may well have travelled by train on the Waterloo line, but not stopping at Whitton or North Sheen: those stations were only opened in 1930.

And, look! They have two pretty strong veterans on the top two boards, no doubt delighted when a new club opened on their doorstep.

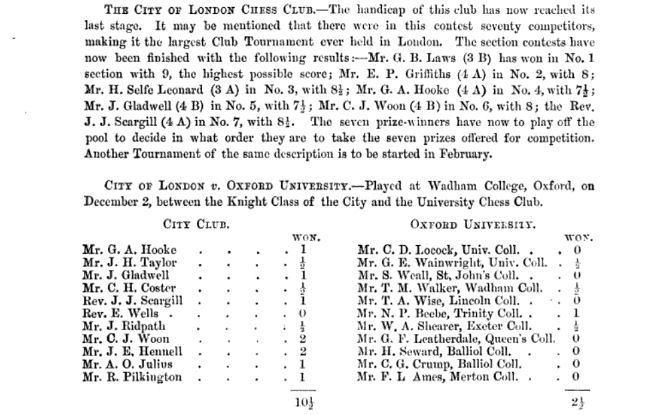

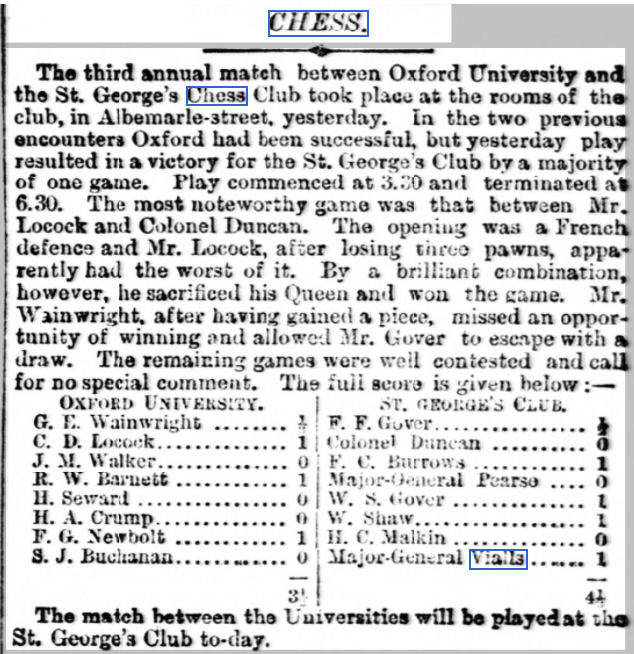

Here they are again, more than forty years earlier, playing again on the top two boards for the City of London Chess Club Knight Class in a match against Oxford University.

Messrs Hooke and Taylor were playing in the Knight Class of the City of London Chess Club: they’d have received odds of a knight when playing master strength opponents in the club handicap tournament. The Morning Post (4 December 1882) reported: “The result was a surprise to both parties, and appeared to puzzle the winners just as it did the losers.”

Mr Hooke’s opponent was the very interesting Charles Dealtry Locock, who will surely feature in a future Minor Piece. Mr Taylor faced George Edward Wainwright, a familiar name to Minor Piece readers. (Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4)

This wasn’t the first appearance of Mr Hooke in the chess news. His first appearance was in the 11th Counties Chess Association Meeting at the Manor House Hotel, Leamington in October 1881, where he played in the second class section, winning this game. You can click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up window.

The up-and-coming Joseph Henry Blake from Southampton shared first place in the second class section with George E Walton from Birmingham. The information as to where Hooke finished and how many points he scored seems not to be available. The first three places in the top section were filled by members of the clergy: Charles Edward Ranken, John Owen and William Wayte.

Earlier in 1882 he’d beaten Captain Mackenzie in a simul. He’d also travelled to Manchester for the 12th Counties Chess Association Meeting, where he finished fourth in Class 2 with a score of 7½/11. Here, then, was an ambitious and fast improving young player, keen to play whenever the opportunity arose.

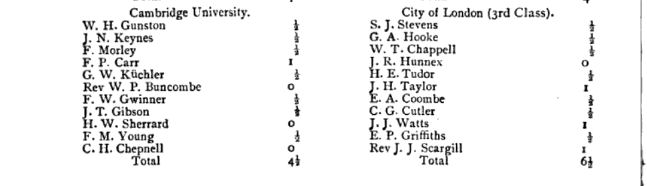

By 1884 George Hooke and John Taylor had both graduated to Class 3 (pawn and two moves). In this match they met a team from Cambridge University.

Mr Hooke again faced an interesting opponent in John Neville Keynes, the father of economist and Bloomsbury Group member John Maynard Keynes. By contrast, Mr Taylor’s opponent, Rev William Pengelly Buncombe, spent much of his life as a missionary in Japan.

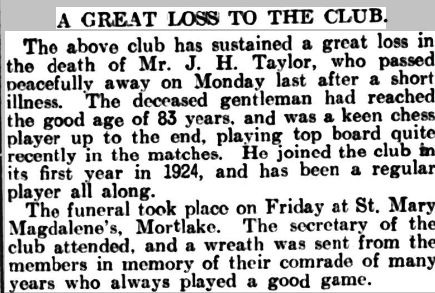

Let’s deal quickly with Mr Taylor. John H Taylor was Irish, born in County Westmeath in 1853, and, by profession a railway accountant, a not uncommon occupation at the time. He was active in the City of London Chess Club in the 1880s and 1890s but seemed to drop out of chess until the Barnes Village club opened its doors, when, in retirement, he threw himself into their activities, right up to the end of his life in 1937.

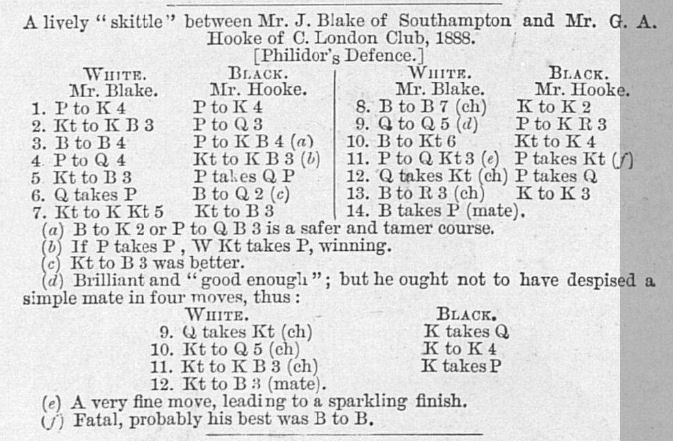

Mr Hooke was rather stronger, and rather more interesting. He’s most famous for a game he lost against the aforementioned Mr Blake, which has been much anthologised, often with the missed brilliancy on move 9 substituted for the actual conclusion, and often also with an incorrect year. Here’s its first appearance in print.

And here it is for you to play through yourself.

You’ll observe that the annotator, not having the benefit of Stockfish 15 to consult, mistakenly refers to Blake’s 11th move as a very fine move. It was a creative try which worked over the board, but Hooke could have won by playing, amongst other moves, 11… Qc8 or Qb8, making room for his king on d8. I’ve always found the 9. Qxf6 variation particularly attractive, with the knights returning to f3 and c3 to deliver mate.

Joseph Henry Blake was another prominent figure with a very long chess career, the latter part of which took place in Kingston. With any luck he’ll be the subject of some Minor Pieces in future.

George Archer Hooke was born in Chelsea on 28 February 1857, the third of twelve children of William Hooke and Harriet Sanders, six of whom tragically died before reaching the age of 20.

Here, from the family archives, is a photograph of William.

The family are elusive in the 1861 census, but in 1871 we find William working as the manager of a furniture depository living in the Parish of St George’s Hanover Square with his wife and eight children. They have no servants living in, which suggests the family was not especially wealthy.

By 1881 they’re at a different address, but still in the same parish. William seems to be in very much the same job. There are six children at home, along with a granddaughter. George, still living at home, is working as a 3rd Class Clerk in the Seamen’s Registry Office of the Board of Trade. He would remain there for the rest of his working life.

It must have been round about that time that he joined the City of London Chess Club, having learnt the game from his father at the age of about 12. He would soon join the North London Chess Club as well.

Moving into the middle of the 1880s, here’s a game from a match between the City of London and St George’s Chess Clubs, in which he faced the Hon Horace Curzon Plunkett, MP, rancher, agricultural reformer and uncle of writer and chess player Lord Dunsany. (He was ranching in Wyoming at the time: this must have been one of his visits back to London.) As the game was unfinished at the call of time it was adjudicated by Zukertort. His verdict was a draw, but Stockfish 15 disagrees, thinking Hooke had a winning position.

In August that year he played in the 15th Counties Chess Association Meeting in Hereford, playing in Class 1A where he shared first place with his former antagonist Charles Dealtry Locock.

The parallel Class 1B tournament was won by George Edward Wainwright, and the two Georges then contested a 14-game match in London, with George H winning by the odd point. This match wasn’t well reported: it’s not clear whether it was a formal play-off match to decide the winner of the Hereford tournament or purely a friendly encounter.

In this league game against an anonymous opponent Hooke brought off a neat finish, giving up a rook to force checkmate in the ending.

In an 1886 match between City of London and St George’s, he encountered one of the Fighting Reverends, Rev William Wayte, who had been one of England’s strongest players back in the 1850s. (You might notice that his Wikipedia page quotes from The Even More Complete Chess Addict, by M Fox and R James.) This time no adjudication was required: George managed to grind out a win with an extra pawn in a rook ending. Towards the end of his life, he mentioned a win against Wayte from 1885 as one of the games that gave him most pleasure: I presume he intended this one, even though the year doesn’t quite tally.

In the same year, 1886, George won a share of the brilliancy prize for this game in the City of London Chess Club Handicap Tournament against an opponent who got stuck in the mud adopting an unusual defence: we’d now call it a Hippopotamus.

In 1886 Hooke took part in the Amateur Championship of the 2nd British Chess Association Congress in London, scoring an outstanding success. Walter Montagu Gattie won with a score of 15/18, and George Archer Hooke featured in a three-way tie for second with Antony Alfred Geoffrey Guest and George Edward Wainwright. Unfortunately, few of the games from this tournament have been published.

Although most of the games took place during the summer, it was only concluded in October, by which time George was involved in another tournament. This was the British Chess Club 2nd Class Tournament in which he again finished in second place. His score of 3½/5 left him half a point behind Scottish champion Daniel Yarnton Mills. Here’s their game, which resulted in a draw.

Handicap tournaments were a big feature of every competitive chess club at the time, and for many years later. Perhaps they should be revived. They worked something like this.

The players were grouped into classes according to playing strength. If you played someone one class below you, you played Black without your f-pawn. Against someone two classes below you and you were again Black without your f-pawn, but White got to play two moves at the start of the game. Against an opponent three classes below you, you’re White but playing without your queen’s knight. and, against an opponent four classes below you you’re again White and this time without your queen’s rook.

Here’s how George Hooke defeated a player two classes below him who foolishly launched a kamikaze attack right from the opening rather than playing solid, sensible moves. (We start the game with the white pawn already on e4.)

By now, it seems that, while George Archer Hooke continued to play regularly in matches and club tournaments, he no longer had the time to travel to places like Manchester and Hereford for congresses. Perhaps his work with the Board of Trade was taking up more of his time: as a young man of considerable abilities approaching his 30th birthday he would doubtless have been promoted by now.

Perhaps there was another reason as well.

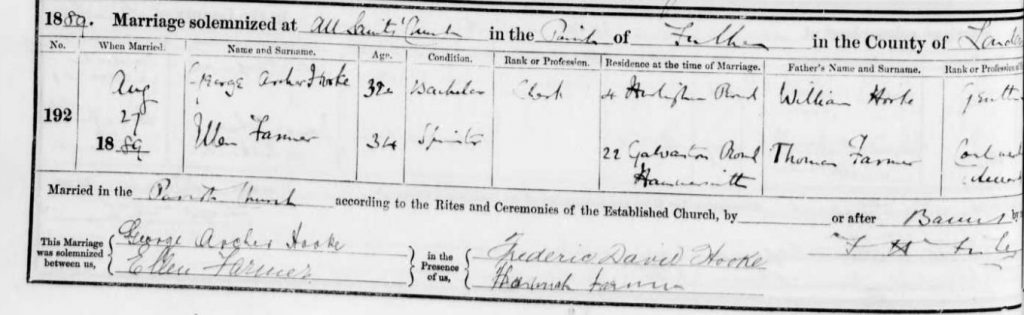

Here he is, on August 27 1889, now aged 32, marrying 34 year old Ellen Farmer at All Saints Church, Fulham, right by Putney Bridge. Congratulations to the happy couple!

And here, for now, we’ll leave George Archer Hooke, a strong amateur chess player, a high-flying civil servant and now a married man who would waste little time starting a family.

You already know that he was still playing chess in the 1920s so there’s lots more to tell.

You’ll find out what happened next in the second instalment of the story of George Archer Hooke, coming very soon to a Minor Piece near you.

Acknowledgements and sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

EdoChess (George Archer Hooke’s page here)

BritBase

chessgames.com

Chess Notes (Edward Winter)

Chess Scotland

Hooke Family History (many thanks to Graham Hooke)

Brian Denman

Gerard Killoran

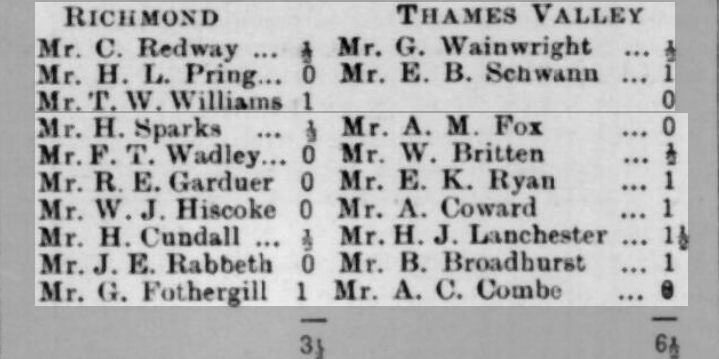

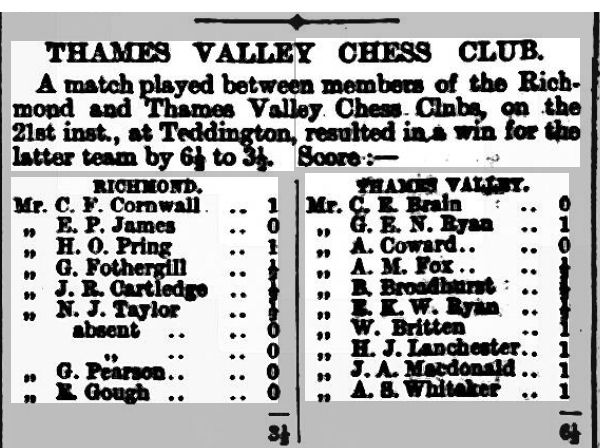

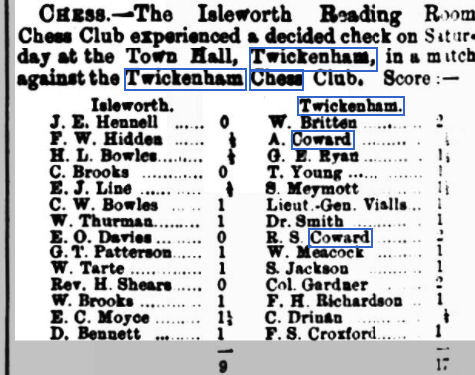

You might have seen this in the previous Minor Piece. Consider for a moment the Thames Valley team. There on board 6 or thereabouts is Arthur Coward, father of Noël. A board (or possibly two) below him is Mr HJ Lanchester, another man with an interesting family. (I note, en passant, that Augustus Campbell Combe on board 10, a Stock Exchange Clerk, was Wallce Britten‘s brother-in-law.)

Henry Jones Lanchester was an architect and surveyor, born in Islington on 5 January 1834, so he was 65 at the time of this match.

He lived at various addresses in London before moving to Brighton in about 1870, where he worked on the Stanford Estate and Palmeira Mansions. But he was badly affected by the property slump of the late 1880s and moved back to London with his family, settling in Battersea, not far from Clapham Common.

The good news for Henry was that he now had more time to play chess and immediately joined Balham Chess Club, where he won 2nd prize in their 1888-89 tournament and played on a high board for them in matches against neighbouring clubs as well as being selected to represent Surrey in county matches.

By 1895 he’d moved to a house called Salvadore on Kingston Hill, and the 1901 census found him at Ripley House, Acacia Road, New Malden, on the same estate as Richmond top board IM Gavin Wall, not to mention David Heaton. Living close to the station, it would have been easy for him to catch the train to Teddington to play for Thames Valley Chess Club, unless he preferred a ride in one of those new-fangled motor cars.

But Thames Valley wasn’t his only chess club: he was also playing for Surbiton. Here he is, in 1901, taking second board in two matches and gallantly agreeing a draw against Mrs Donald Anderson of the Ladies Chess Club in a favourable position. Mrs Anderson (née Gertrude Alison Field) won the British Ladies Championship in 1909 and 1912, so this was a good result.

In 1903 he had a wasted journey to Richmond as, all too typically for the home club at the time, two of their players failed to turn up. Didn’t they have any social players there to fill in? Fortunately, our excellent match captains are far better organised today.

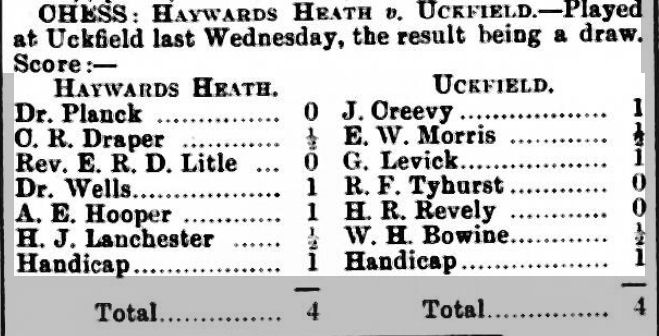

By the middle of the decade he had returned to Sussex, settling in Lindfield, near Haywards Heath, whose chess club he promptly joined

Here’s a 1906 match card.

I’m not sure why both teams scored a Handicap point on board 7, but there you go.

Haywards Heath’s top board, Dr Charles Planck (no relation, as far as I know, to Max), was a doctor and psychiatrist running the local lunatic asylum, a type of institution with which Lanchester, as you’ll find out later, had had previous experience. He was also one of England’s leading problemists, having co-authored, back in 1887, a book called The Chess Problem with fellow problemists Henry John Clinton Andrews, Edward Nathan Frankenstein and Benjamin Glover Laws. Another spoiler alert: read on for a very different Frankenstein.

Henry Jones Lanchester also played correspondence chess, playing for Sussex in matches against other counties. He died at his home in 1914, on his 80th birthday.

Here’s a game from one of those correspondence matches. His opponent was born Emily Beetles Nicholls in Guildford in 1872. Her father, Edward, was high up in the Inland Revenue and seemed to move around the country a lot. Click on any move for a pop-up board.

Probably not a game which showed him at his best. The Vienna Game is devastating against an unprepared opponent and his natural third move just leads to a lost position, 6. d5 would have been much better than Mrs Bush’s e5, which allowed Henry back into the game. (Thanks to Brian Denman for sending me this, which was published in the Lowestoft Journal (23 Jan 1909).)

Here, then, was a man who must have played chess all his life, but, it seems, only took up competitive chess on his retirement (or perhaps semi-retirement) from his career as an architect and surveyor.

For further information on Henry Jones Lanchester:

Wikipedia

Grace’s Guide (also links to his sons)

He must also have taught his children chess. Some of them had very interesting lives.

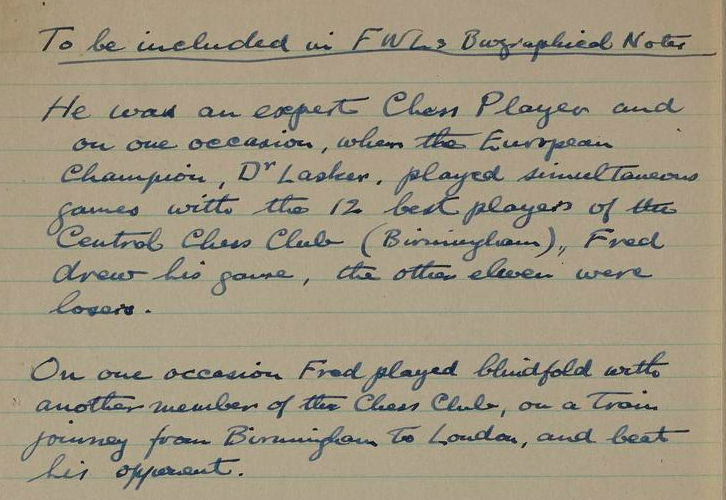

Henry had married Octavia Ward, a mathematics and Latin tutor, in 1863. Their children were Henry Vaughan (1863), Mary (1864), Eleanor Caroline (1866), Frederick William, known as Fred (1868), Francis, known as Frank (1870: his twin brother Charles didn’t survive), Edith, known as Biddy (1871), Edward Norman (1873) and George Herbert (1874). Henry junior became, like his father, an distinguished architect. Mary and Eleanor both became artists. Edward emigrated to New Zealand, later moving to Australia and earning a living as a signwriter.

The other three brothers, Fred, Frank and George, were a lot more interesting.

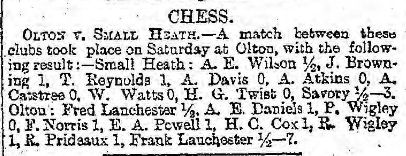

Fred Lanchester was one of the most remarkable engineers and inventors of his time. In 1888 he took a job with a gas engine company in Birmingham, and, in his spare time, started working on designing motor cars. In 1895 he completed a four-wheeled vehicle powered by a petrol engine. In between his work and his vehicle, he also found time to play chess. Here he is, playing on top board for his local club, Olton (near Solihull), with his brother Frank, clearly an inferior player, on bottom board.,

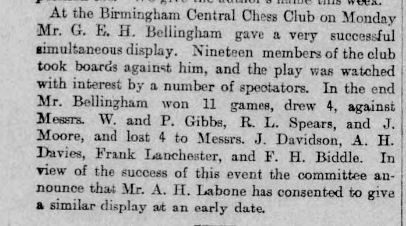

In 1898, he won a game in a simul against the leading West Midlands player of his day, George Edward Horton Bellingham. You’ll notice an incorrectly initialled mention of our old friend Oliver Harcourt Labone.

According to his brother George he also beat none other than Emanuel Lasker in a simul.

However, George’s account doesn’t tally with any of the Lasker simuls given by Richard Forster in his definitive list here.

| 1 Mar 1897 | Birmingham | 31 | 26 | 3 | 2 | |

| 2 Mar 1897 | Birmingham (consultation) | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 Dec 1898 | Birmingham, Central C.C. | 25 | 13 | 9 | 1 | Various games were adjudicated, two left undecided. |

| 23 Nov 1900 | Birmingham, Temperance Institute | c10 | c10 | 0 | 0 | Vlastimil Fiala in the Quarter for Chess History, no. 6/2000, pp. 382f. claimed a score of 25 wins, but it was not possible to verify this score indepedently. The Cheltenham Examiner, 28 November 1900, indicated “less than a dozen” and the Birmingham Weekly Post, 1 December 1900, spoke of “a meagre attendance”. |

| 17 Mar 1908 | Birmingham C.C. | 28 | 23 | 3 | 2 |

In December 1899 Fred, Frank and George created the Lanchester Engine Company to build and sell motor cars to the general public. George was also a brilliant engineer, while Frank was the sales manager. For several decades Lanchester was one of the most famous makes of motor car in the country.

The name Lanchester was commemorated in 1970 with the creation of Lanchester Polytechnic, now Coventry University.

Perhaps the family’s achievements, especially those of Fred, are unfairly forgotten today. They certainly deserve to be remembered as pioneers of the early motor car industry. It’s good to know that Fred was also a pretty good chess player.

For more information on the Lanchester brothers:

Wikipedia (Fred)

Wikipedia (George)

Wikipedia (Lanchester Motor Company)

Lanchester Interactive Archive

Their sister Edith (Biddy) was another matter entirely.

Biddy became a socialist and suffragette, living ‘in sin’ (as they used to say) with a working-class Irishman named James ‘Shamus’ Sullivan: the couple both disapproved of the institution of marriage.

Horrified by this, in 1895 her father and brothers kidnapped her and sent her to the lunatic asylum (it’s now, famously, The Priory) on the grounds that only an insane person could possibly become a socialist. The asylum could find nothing wrong with her and released her a couple of days later. In 1897 she became Eleanor Marx’s secretary. The job didn’t last long as Eleanor committed suicide the following year. Perhaps Biddy and Eleanor also played chess: I’d imagine Biddy learnt the moves from her father and brothers, and Eleanor usually beat her father (Karl, of course) at chess.

Biddy and Shamus’s first child, a son called Waldo, was born in 1897. He became a famous puppeteer, founding the Lanchester marionettes, a puppet theatre which ran from 1935 to 1962.

Their second child, a daughter whom they named Elsa, was born in 1902. Elsa took up dancing as a child, then worked in theatre and cabaret, also obtaining small roles in films.

In 1927 she married the actor Charles Laughton and, after playing Anne of Cleves to his Henry in The Private Life of Henry VIII, the couple moved to Hollywood where Elsa found fame in 1935 for her starring role in The Bride of Frankenstein. (Be careful not to confuse her with Miriam Samuel, the bride of the aforementioned Edward Nathan Frankenstein.) Elsa continued to perform on the silver screen, mostly in cameo roles, up to 1980, including playing Katie Nanna in Mary Poppins.

Of course, there’s something you all want to know. Did Elsa, like her grandfather and uncles, play chess. Why yes, she certainly did. VIctoria Worsley’s recent (2021) biography, Always the Bride, tells of her playing chess with a friend on a car journey in 1936. Chess wasn’t her only game, either. Here she is playing draughts against Charles Laughton.

As Elsa’s grandfather played chess on the adjacent board to Noël Coward’s father, you might also want to know whether they ever appeared in the same film. Sadly not, although Coward provided some dialogue for the 1957 Agatha Christie adaptation Witness for the Prosecution, starring Tyrone Power and Marlene Dietrich along with Laughton and Lanchester. (Elsa won a Golden Globe award for the Best Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture.)

More about Biddy and Elsa:

Wikipedia (Biddy)

Wikipedia (Elsa)

IMDb (Elsa)

This was the life and chess career of Henry Jones Lanchester, a man who shared a mutual friend with Frankenstein, and whose granddaugher was the Bride of Frankenstein. Henry was also the head of a remarkable chess-playing family, pioneers in both motoring and movies.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

Grace’s Guide

IMDb

Lanchester Interactive Archive

Other sources mentioned in the text

Richard Forster: Lasker’s Simultaneous Exhibitions. www.emanuellasker.online (2022).

You’ve seen this before:

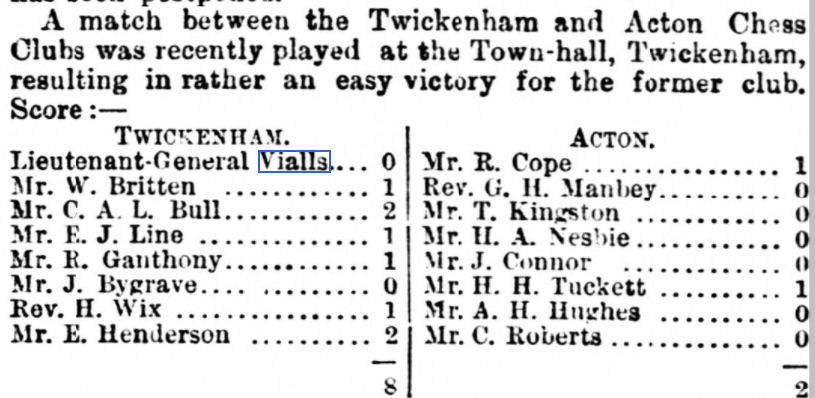

You’ll notice Twickenham fielded two military men in this match.

We need to find out more about them.

The rank of Lieutenant-General is the third highest in the British Army behind only General and Field Marshal: an officer in charge of a complete battlefield corps.

George Courtenay (Courtney in some records) Vialls is our man. He must have been pretty good at manoeuvring the toy soldiers of the chessboard as well as real soldiers in real life battles.

In this match he was on top board, ahead of the more than useful Wallace Britten, but this might, I suppose, have been due to seniority of rank rather than chess ability.

There are a couple of other interesting names in the Twickenham team here, to whom we’ll return in subsequent articles.

However, he was good enough to score a vital win for St George’s Club against Oxford University two years earlier.

You’ll note the two other high ranking army officers in the St George’s team, as well as two significant chess names on Oxford’s top boards (who may well be the subject of future Minor Pieces).

Vialls must have been a prominent member of St George’s Club as he was on the organising committee for the great London Tournament of 1883.

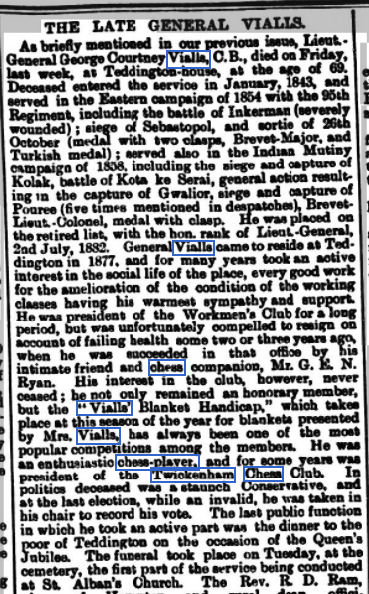

An obituary, from 1893, provides some useful information.

We learn that he was an intimate friend (no, not in that sense, but read on for some more intimate friends) of George Edward Norwood Ryan, and that he was a former President of Twickenham Chess Club.

Going back to the beginning, George Courtenay Vialls was the son of the Reverend Thomas Vialls, a wealthy and rather controversial clergyman. In 1822, prosecuted his gardener for stealing two slices of beef, which in fact his aunt had given him for lunch. He was himself up before the law two years later, accused of whipping his sister-in-law. Thomas had inherited Radnor House, by the river in Twickenham, from an uncle in 1812, and it was there, in 1824 that George was born.

He joined the army in 1843, serving in the 95th Regiment of Foot, and the 1851 census found him living in Portsmouth with his wife and infant daughter, awaiting his next assignment. That came in 1854 when his regiment embarked for Turkey and the Crimean War. At the Battle of Inkerman in November he was severely wounded and his commanding officer, Major John Champion, was killed in action. The regiment suffered further losses due to cold and disease. It was remarked that “there may be few of the 95th left but those few are as hard as nails”.

In 1856 they returned home, but were soon off again, at first to South Africa, but they were quickly rerouted to India to help suppress what was then called the Indian Mutiny, but we now prefer to call the Indian Rebellion.

Looking back from a 21st century perspective (as it happens I’ve just been reading this book), you’ll probably come to the conclusion that this was far from our country’s finest hour, but at the same time you might want to admire the courage of those on both sides of the conflict, and note that Vialls was five times mentioned in despatches.

In 1877 he seems to have been living briefly in Manchester, where he started his involvement in chess, taking part in club matches and losing a game to Blackburne in a blindfold simul.

The obituary above tells us that he moved to Teddington in 1877 (he was in Manchester in December that year so perhaps it was 1878), but the 1881 census found him and his wife staying with his wife’s sister’s family on a farm in Edenbridge, Kent. Perhaps they were just on holiday.

By 1891 they were in Teddington House, right in the town centre. It was roughly behind the bus stop where the office block is here, and if you spin round you’ll see the scaffolding surrounding Christchurch, in whose church hall Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club met for some time until a few years ago.

Before we move on, a coincidence for you. At about the same time the chess players of Northampton included a Thomas H Vials or Vialls, who was also the Secretary of Northamptonshire County Cricket Club, as well as a Walter E Britten, neither of whom appear to have been related to their Twickenham namesakes.

Our other military chesser from Twickenham, Colonel Thomas George Gardiner, was slightly less distinguished as both an army officer and a chess player, playing on a lower board in a few club matches in the early 1880s. As you’ll see, he came from an interesting family with some unexpected connection.

If you know Twickenham at all you’ll recognise this scene. The River Thames is behind you. Just out of shot on the left is Sion Row, where Sydney Meymott lived for a short time. On the right, just past Ferry Road, you can see the White Swan.

On the left of the photograph is Aubrey House, and the smaller house to its right with the pineapples on the gateposts is The Anchorage, also known in the past as Sion Terrace. As it happens I used to visit this house once a week in the mid 2000s to teach one of my private chess pupils.

The houses are discussed in this book, which I also referred you to in the Meymott post. At some point both Aubrey House and The Anchorage came into the possession of the Gardiner family: Thomas George Gardiner senior and his family were there in 1861 after he’d retired from work with the East India Company. The younger Thomas George had been born in Ham, just the other side of the river, in 1830 and chose an Army career, joining the Buffs (East Kent Regiment). He married in Richmond in 1857 and in 1861 was living in Twickenham with his wife and her mother’s family, described as a Major in the Army on half pay.

He apparently bought Savile House, out towards Twickenham Green, in 1870, but the family weren’t there in 1871. Perhaps he was serving abroad: his wife, ‘the wife of a colonel’, was still with her family, in Cross Deep Lodge, just a short walk from Twickenham Riverside. By 1881 he had retired, and the family were indeed living in Savile House. The building is long demolished: Savile Road marks the spot.

He sold the house in 1889, and the 1891 census unexpectedly found him in Streatham. Perhaps he joined one of the local chess clubs in the area. His wife died in 1896, and by 1901 he’d moved back to his father’s old residence, Aubrey House, along with a widowed daughter. He died in 1910: here’s his obituary from the Army & Navy Gazette.

The 1911 census records his daughter still in Aubrey House, along with three servants.

It’s worth taking a look at his mother, Mary Frances Grant (1803-1844), who was one of the Grants of Rothiemurchus, whose family, entirely coincidentally, are now the Earls of Dysart, the Tollemache family having died out. The Tollemache family owned Ham House until its acquisition by the National Trust in 1948, and a very short walk from Aubrey House will take you to Orleans Gardens, from where you can see Ham House across the river.

One of Mary’s brothers, William, married Sarah Elizabeth Siddons, whose grandmother was the celebrated actress Sarah Siddons. Another brother, John Peter Grant, married Henrietta Isabella Philippa Chichele Plowden. One of their daughters, Jane, married Richard Strachey: their famous offspring included the biographer and Bloomsbury Group member Lytton Strachey. One of their sons, the oddly named Bartle Grant, married Ethel Isabel McNeil. Their son was the artist and Bloomsbury Group member Duncan Grant. Duncan and his cousin Lytton had intimate friendships with very many people, including each other, and also including the economist John Maynard Keynes. His father, John Neville Keynes played chess for Cambridge against Oxford between 1873 and 1878, the last four times on top board. Strachey and Keynes also had relationships with WW1 and WW2 codebreaker Dilly Knox, who, until his death in 1943, worked closely with Alan Turing at Bletchley Park. His other colleagues there included leading chess players such as Hugh Alexander and Stuart Milner-Barry.

So there you have it. George Courtenay Vialls and Thomas George Gardiner: two Twickenham men with distinguished military careers, both from very privileged and well-connected backgrounds. The Twickenham aristocracy, you might think, with their large riverside houses. Two men who, after decades commanding troops in real wars, spent their retirement commanding wooden soldiers on a chequered board.

We’re beginning to see a pattern within the membership of Twickenham Chess Club in the 1880s.

Who will we discover next? Join me soon for more Minor Pieces.

Sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

Google Maps

Twickenham Museum website

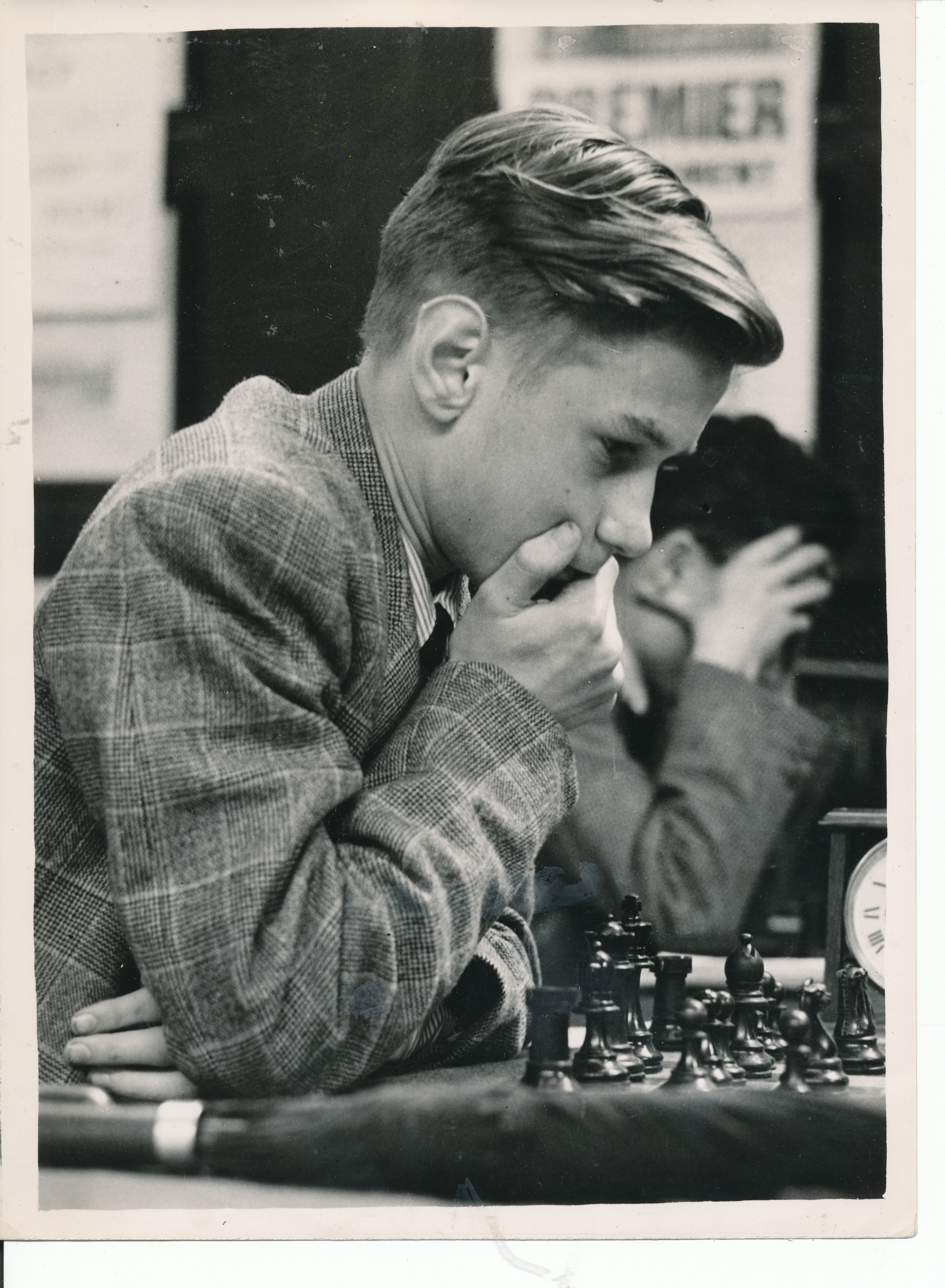

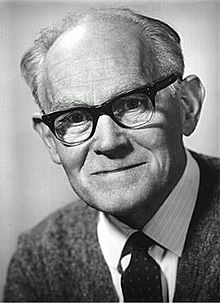

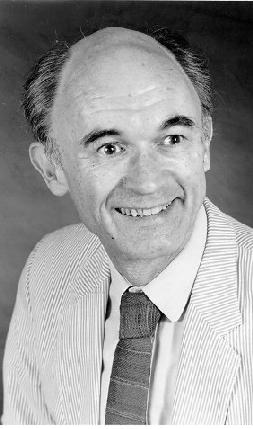

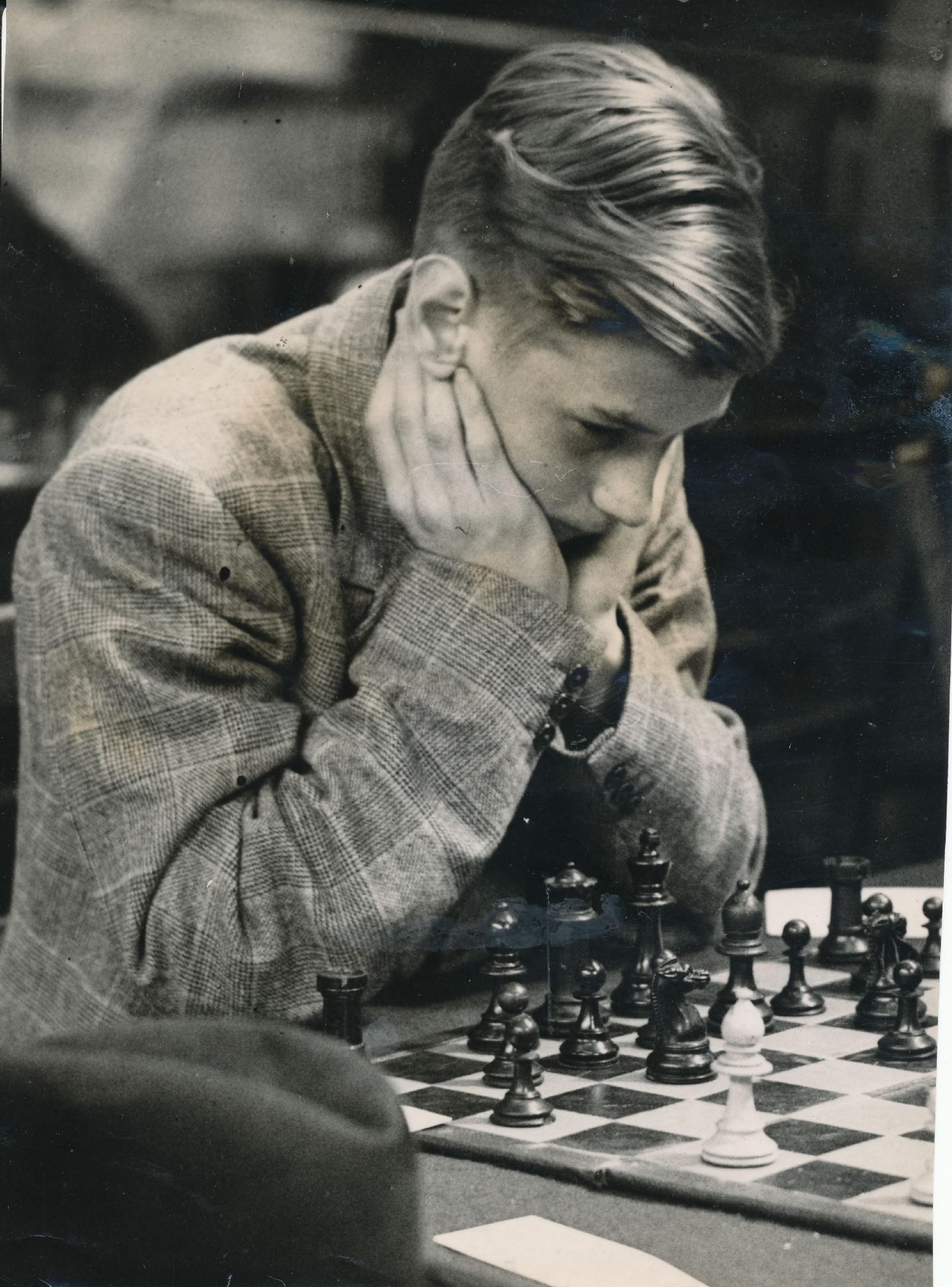

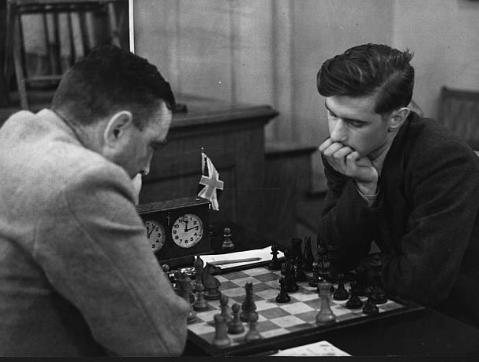

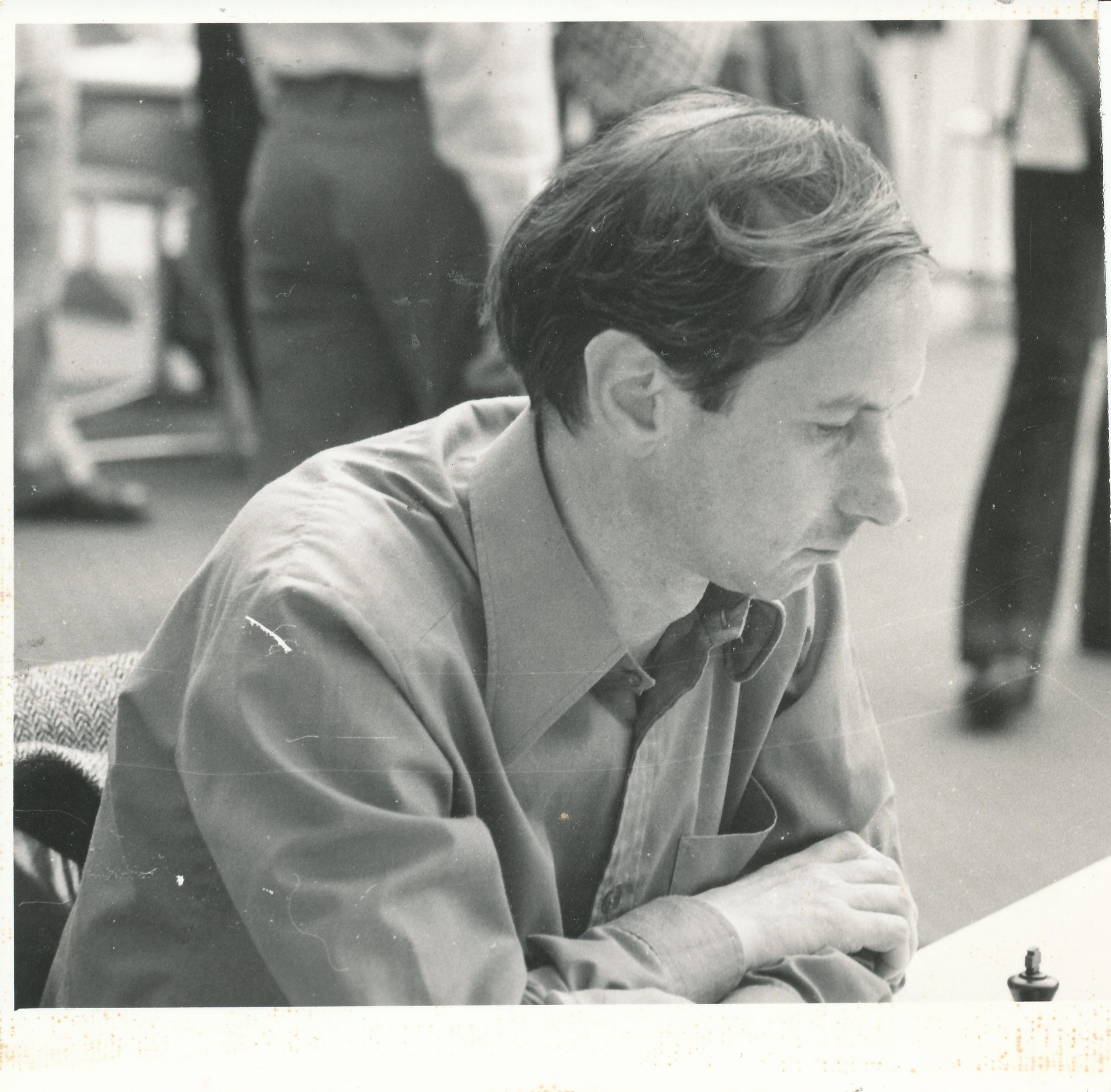

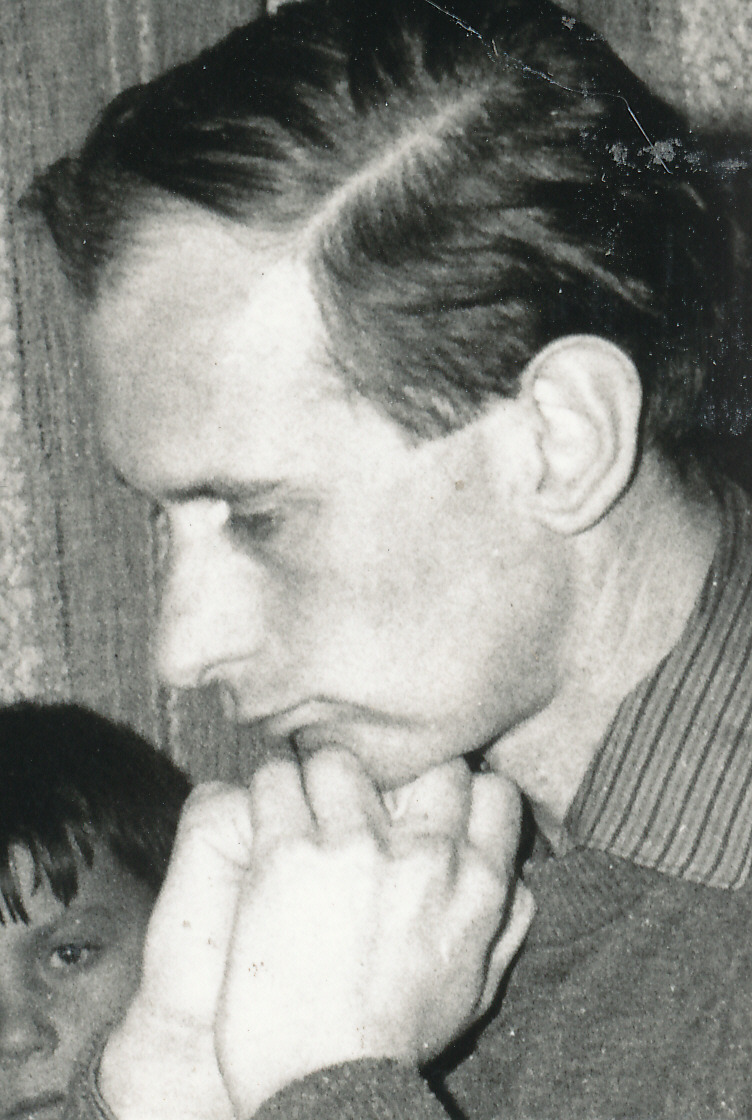

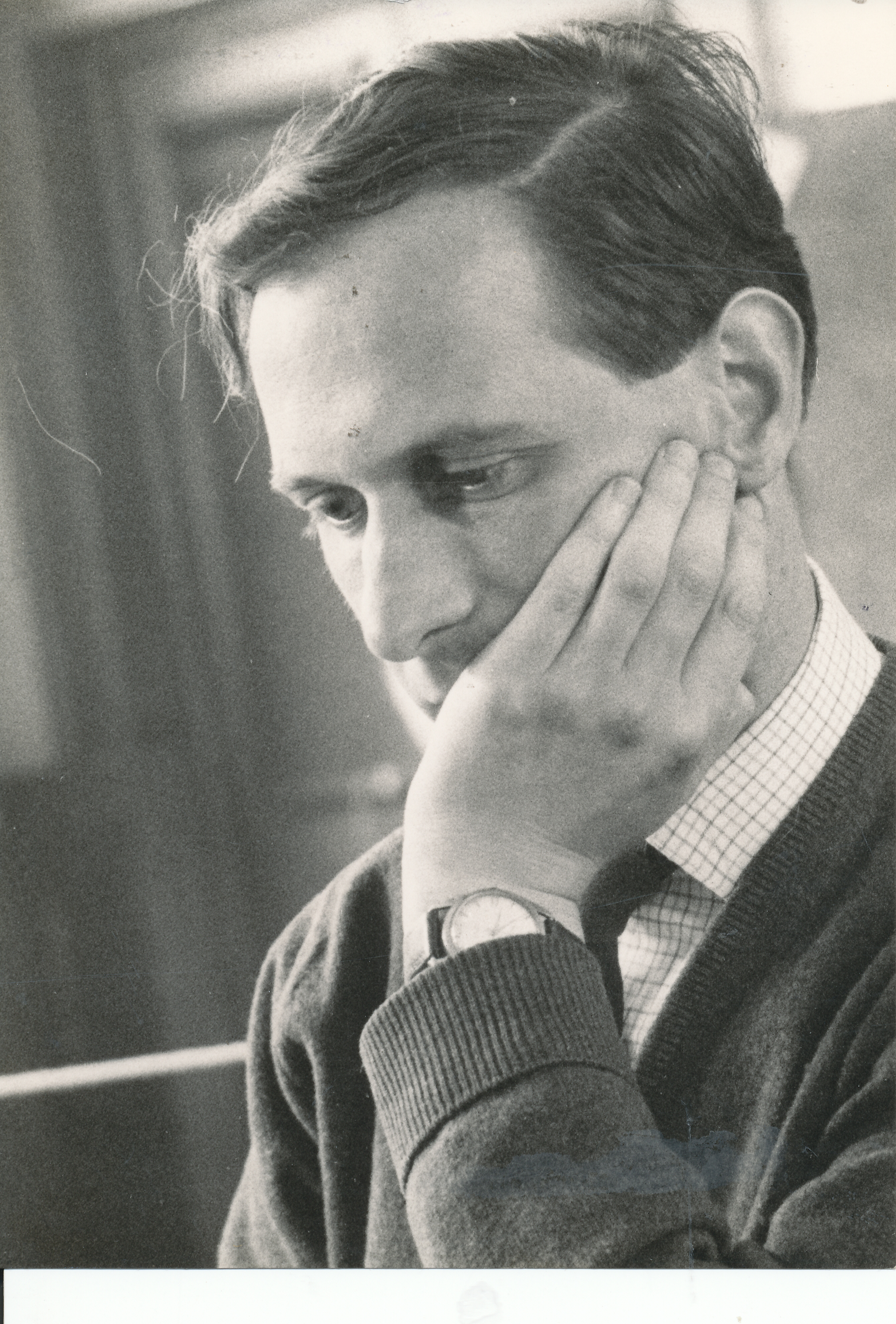

BCN remembers GM Dr. Jonathan Penrose OBE who passed away on Tuesday, November 30th, 2021.

In the 1971 New Years Honours List Jonathan was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) The citation read “For services to Chess.”

In 1993 following representations by Bob Wade and Leonard Barden FIDE granted the title of Grandmaster to Jonathan. Here is a detailed discussion of that process. Note that this was not an Honorary title (as received by Jacques Mieses and Harry Golombek).

From British Chess (Pergamon Press, 1983) by Botterill, Levy, Rice and Richardson : (article by George Botterill)

“Penrose is one of the outstanding figures of British chess. Yet many who meet him may not realize this just because he is one of the quietest and most modest of men. Throughout the late 1950s and the whole of the 1960s he stood head and shoulders above any of his contemporaries.

His extraordinary dominance is revealed by the fact that he won the British championship no less than ten times (1958-63 and 1966-69, inclusive), a record that nobody is likely to equal in the future.

At his best his play was lucid, positionally correct, energetic and tactically acute. None the less, there is a ‘Penrose problem’: was he a ‘Good Thing’ for British chess? The trouble was that whilst this highly talented player effectively crushed any opposition at home, he showed little initiative in flying the flag abroad. There is a wide-spread and justifiable conviction that only lack of ambition in the sphere of international chess can explain why he did not secure the GM title during his active over-the-board playing career.

It would be unjust, however, to blame Penrose for any of this. The truth is simply that he was not a professional chessplayer, and indeed he flourished in a period in which chess playing was not a viable profession in Britain. But even if the material awards available had been greater Penrose would almost certainly have chosen to remain an amateur. For he was cast in that special intellectual and ethical tradition of great British amateurs like H. E. Atkins, Sir George Thomas and Hugh Alexander before him.

His family background indicates early academic inclinations in a cultural atmosphere in which chess was merely a game something at which one excelled through sheer ability, but not to be ranked alongside truly serious work. It is noteworthy that Penrose, unique in this respect amongst British chess masters, has never written at any length about the game. He has had other matters to concentrate on when away from the board, being a lecturer in psychology. (His father, Professor L. S. Penrose, was a distinguished geneticist.)

Being of slight physique and the mildest and most amiable of characters, it is probably also true that Penrose lacked the toughness and ‘killer instinct’ required to reach the very top. Nervous tension finally struck him down in a dramatic way when he collapsed during play in the Siegen Olympiad of 1970. We can take that date as the end of the Penrose era.

Since, then though he has not by any means entirely given up, his involvement in the nerve-wracking competitions of over-the-board play has been greatly reduced. instead he has turned to correspondence chess, which is perhaps the ideal medium for his clear strategy and deep and subtle analysis. So Penrose’s career it not over. He has moved to another, less stressful province of the kingdom of chess.

For the first game, however, we shall turn the clock right back to 1950 and the see the Penrose in the role of youthful giant killer.

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (BT Batsford, 1977) by Harry Golombek :

“British international master and ten times British Champion, Penrose was born in Colchester and came from a chess-playing family.

His father and mother (Margaret Leathes) both played chess and his father, Professor Lionel Sharples Penrose, in addition to being a geneticist of world-wide fame, was a strong chess-player and a good endgame composer. Jonathan’s older brother Oliver, was also a fine player.

Roger Penrose won the Nobel prize for physics in 2020.

Shirley Hodgson (née Penrose) is a high flying geneticist.

Jonathan learnt chess at the age of four, won the British Boys championship at thirteen and by the time he was fifteen was playing in the British Championship in Felixstowe in 1949.

A little reluctant to participate in international tournaments abroad, he did best in the British Championship which he won a record number of times, once more than HE Atkins. He won the title consecutively from 1958 to 1963 and again from 1966 to 1969.

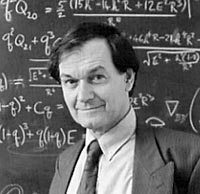

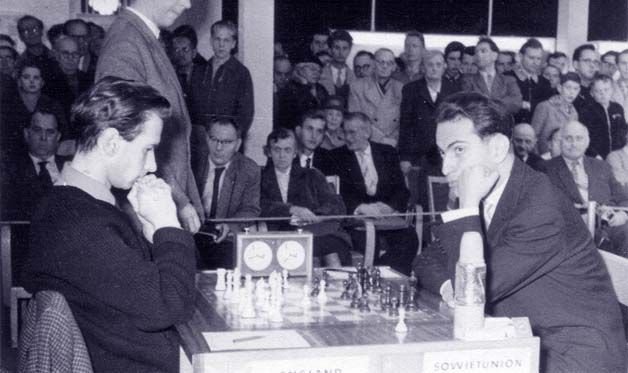

He also played with great effect in nine Olympiads. Playing on a high board for practically all the time, he showed himself the equal of the best grandmasters and indeed, at the Leipzig Olympiad he distinguished himself by beating Mikhail Tal, thereby becoming the first British player to defeat a reigning World Champion since Blackburne beat Lasker in 1899.

A deep strategist who could also hold his own tactically, he suffered from the defect of insufficient physical stamina and it was this that was to bring about a decline in his play and in his results. He collapsed during a game at the Ilford Chess Congress, and a year later, at the Siegen Olympiad of 1970, he had a more serious collapse that necessitated his withdrawal from the event after the preliminary groups had been played. The doctors found nothing vitally wrong with him that his physique could not sustain.

He continued to play but his results suffered from a lack of self-confidence and at the Nice Olympiad of 1974 he had a wretched result on board 3, winning only 1 game and losing 6 out of 15.

Possibly too his profession (a lecturer in psychology) was also absorbing him more and more and too part less and less in international and national chess.

Yet, he had already done enough to show that he was the equal of the greatest British players in his command and understanding of the game and he ranks alongside Staunton, Blackburne, Atkins and CHO’D Alexander as a chess figure of world class.”

Here is his Wikipedia entry

From The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper & Whyld :

“The leading English player during the 1960s, International Master (1961), International Correspondence Chess Master (1980), lecturer in psychology. Early in his chess career Penrose decided to remain an amateur and as a consequence played in few international tournaments. He won the British Championship from 1958 to 1963 and from 1966 to 1969, ten times in all (a record); and he played in nine Olympiads from 1952 to 1974, notably scoring + 10=5 on first board at Lugano 1968, a result bettered only by the world champion Petrosyan.

In the early 1970s Penrose further restricted his chess because the stress of competitive play adversely affected his health.”

The second edition (1996) adds this :

“He turned to correspondence play, was the highest rated postal player in the world 1987-9, and led the British team to victory in the 9th Correspondence Olympiad.”

Here is a discussion about Jonathan on the English Chess Forum

From The Encyclopedia of Chess (Robert Hale, 1970 & 1976) by Anne Sunnucks :

“International Master (1961) and British Champion in 1958 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1966, 1967, 1968 and 1969.

Jonathan Penrose was born in Colchester on 7th October 1933, the son of Professor LS Penrose, the well-known geneticist, who was also a strong player and composer of endgame studies.

The whole Penrose family plays chess and Jonathan learned the game when he was 4. At the age of 12 he joined Hampstead Chess Club and the following year played for Essex for the first time, won his first big tournament, the British Boys’ Championship, and represented England against Ireland in a boy’s match, which was the forerunner of the Glorney Cup competition, which came into being the following year.

By the time he was 17 Penrose was recognised as one of the big hopes of British Chess. Playing in the Hastings Premier Tournament for the first time in `1950 – 1951, he beat the French Champion Nicholas Rossolimo and at Southsea in 1950 he beat two International Grandmasters, Effim Bogoljubov and Savielly Tartakower.

Penrose played for the British Chess Federation in a number of Chess Olympiads since 1952. In 1960, at Leipzig, came one of the best performances of his career, when he beat the reigning World Champion, Mikhail Tal. He became the first British player to beat a reigning World Champion since JH Blackburne beat Emmanuel Lasker in 1899, and the first player to defeat Tal since he won the World Championship earlier that year. Penrose’s score in this Olympiad was only half-a-point short of the score required to qualify for the International Grandmaster title.

His ninth victory in the British Championships in 1968 equalled the record held by HE Atkins, who has held the title more times than any other player.

Penrose is a lecturer in psychology at Enfield College of Technology (now Middlesex University) and has never been in a position to devote a great deal of time to the game. He is married to a former contender in the British Girls Championship and British Ladies’s Championship, Margaret Wood, daughter of Frank Wood, Hon. Secretary of the Oxfordshire Chess Association.

Again from British Chess: “In updating this report we find striking evidence of Penrose’s prowess as a correspondence player. Playing on board 4 for Britain in the 8th Correspondence Chess Olympiad he was astonishingly severe on the opposition, letting slip just one draw in twelve games! Here is one of the eleven wins that must change the assessment of a sharp Sicilian Variation.”

Penrose was awarded the O.B.E. for his services to chess in 1971.”

Penrose was Southern Counties Champion for 1949-50.

In 1983 Jonathan became England’s fifth Correspondence Grandmaster (CGM) following Keith Richardson, Adrian Hollis, Peter Clarke and Simon Webb.

A database of JPs OTB games may be found here.

Sadly, there is no existent book on the life and games of Jonathan Penrose: a serious omission in chess literature.

Here is his Wikipedia entry.

An extensive Guardian obituary from Leonard Barden may be found here.

An interview from March 2000 with correspondence expert, Dr. Tim Harding may be found here.

On the 7th of October 2023 the Jonathan Penrose chess park was opened at The Mercury Theatre, Colchester enabled by funding and support from various sources.

Working Mens’ Clubs in Twickenham and surrounding areas had been meeting each other for friendly competitions since the early 1870s. These would typically involve some combination of activities such as chess, draughts, whist, cribbage, dominoes and bagatelle.

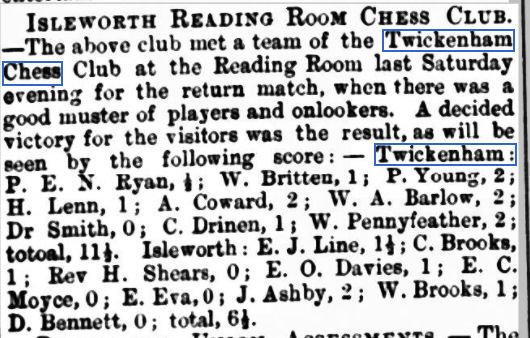

Twickenham Chess Club, for its first few years, seemed to content itself with internal handicap tournaments along with the occasional simultaneous display. It wasn’t until January 1883 that they played their first match against another club. This was against Isleworth Reading Room Chess Club (there has been no chess club in Isleworth for many decades) and resulted in a victory for Twickenham 9 points to 3. Hurrah!

The following month, Twickenham visited Isleworth for a return encounter over 9 boards, with each player having two games against the same opponent. Here’s what happened.

You’ll notice George Edward Norwood Ryan and Wallace Britten on the top two boards. Some of the initials are, as was common in those days, incorrect.

Buoyed by their success, in March they entertained Kingston Chess Club. The Surrey Comet reported that the Twickenham players were most successful, beating their opponents all along the line.

It seems that the Twickenham Chess Club had rapidly established itself as one of the stronger suburban clubs, and that the top boards must have been pretty useful players. As yet I haven’t been able to find any of their games.

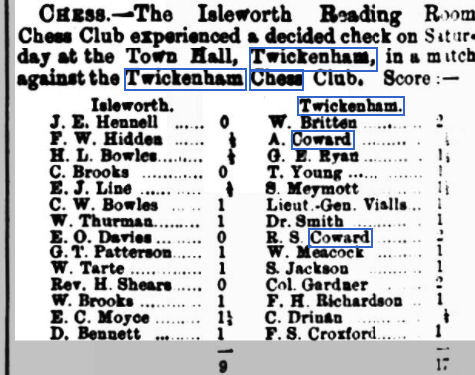

It wasn’t until 1884 that we have a record of another match, again versus the Isleworth Reading Room Chess Club.

There are several interesting names here, but you’ll spot two Cowards in the team. Following his successes the previous year, A Coward had been promoted to second board. The two Brittens turned out not to be related to each other, or to their musical namesake. What about the two Cowards?

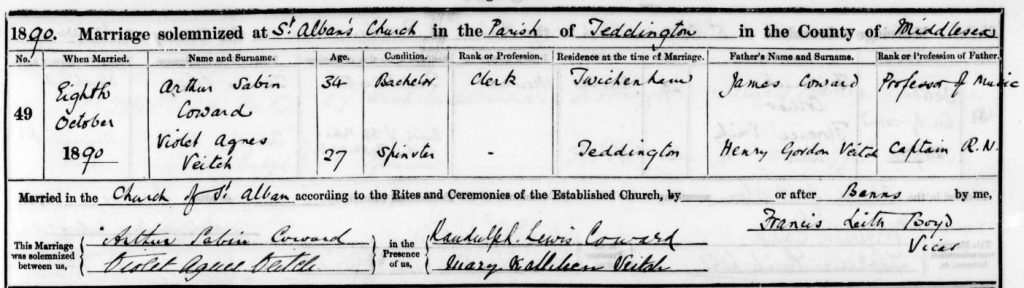

First of all, the weaker Coward’s middle initial is incorrect. They were in fact brothers: Arthur Sabin Coward and Randulph Lewis Coward.

In the 1881 census the family were at 4 Amyand Park Road, Twickenham, right by the station. Arthur was 24 and Randulph 20, both were working as clerks, and they were living with their widowed mother, an annuitant (pensioner), five younger sisters and a servant.

Their late father, James Coward, a victim of tuberculosis the previous year, had been an organist and composer (spoiler alert: not the only organist and composer we’ll encounter in this series)

It’s well worth looking at all his children.

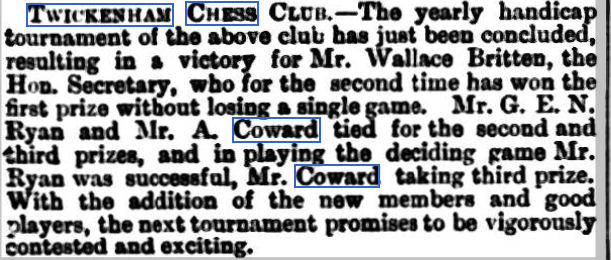

A few days after this Isleworth match, the results of the season’s handicap tournament were in.

Confirmation, then, that Arthur Coward was, along with Wallace Britten and George Ryan, one of the strongest members of Twickenham Chess Club.

With Artie and his brother Randy still young men in their twenties, a great chess future might have been predicted for them. Alas, this was not the case, although they did continue playing for another year or two.

Life, in the shape of family, work and other interests, I suppose, gets in the way.

Let’s visit Teddington and find out.

If you take a stroll along Teddington High Street heading in the direction of the river, you’ll come across two churches. Immediately in front of you, a left turn into Manor Road will take you to Twickenham, while turning right into Broom Road will take you to Kingston. Straight ahead is Ferry Road (another spoiler alert: you’ll be meeting some residents in another Minor Piece), leading to the footbridges across the Thames.

On your left is the quaint 16th century church of St Mary, and on your right a massive edifice which opened its doors in 1889.

Enter Francis Leith Boyd. Boyd, born in Canada, became Vicar of Teddington in 1884 at the age of 28. He was a man of considerable ambition and grandiose ideas, and also famed for his hellfire sermons. St Mary’s wasn’t big enough for him, so he commissioned architect William Niven (grandfather of David) to design a much larger building across the road. It was dedicated to St Alban, but known informally as the Cathedral of the Thames Valley. The money ran out before it was completed: the nave is shorter than intended and the planned 200 foot tower was never built.

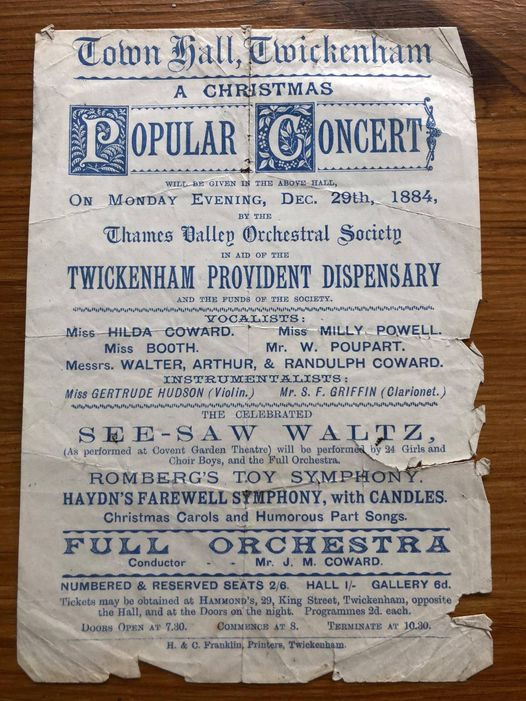

Teddington’s new vicar also enjoyed music, and the combination of music and theatricality must have been very appealing to the musical and theatric Coward family. At some point in the late 1880s they moved from Twickenham to Coleshill Road, Teddington, close to Bushy House, where the National Physical Laboratory would be established in 1900, and threw themselves into musical life at the new church of St Alban’s. Artie and Randy were both very much part of this, and, I suppose, now had no time to pursue their chess careers. The family could even provide a full vocal quartet, with Hilda singing soprano, Walter, later replaced by Percy, singing alto, Arthur singing tenor and Randulph singing bass. They performed everything from the sublime to the ridiculous: Bach’s St John Passion, Spohr’s now forgotten oratorio The Last Judgement, Gilbert and Sullivan operettas and the popular songs and parlour ballads of the day.

Here they are in Twickenham Town Hall, where they would also have played chess, in 1894, with big brother James conducting. (Mr William Poupart is also interesting: he and his family were prominent market gardeners in Twickenham, but none of them, as far as I know, played chess.)

In 1967 the parishioners of Teddington moved back across the road to St Mary’s and St Alban’s soon fell into disrepair. A campaign spearheaded by local Labour Councillor Jean Brown (in the days when this part of the world had Labour Councillors) fought successfully to save the building for community use. It’s still owned by the Church of England but known as the Landmark Arts Centre. If you visit there now you’ll see a plaque commemorating Jean Rosina Brown in the foyer, and there are some information boards at the back which include press cuttings about the Coward family’s involvement with the church. Some 90 years or so ago, Jean and my mother were best friends at school, so, in her memory, I often attend concerts there.

One of the orchestras playing there regularly is the Thames Philharmonia, whose Chair (and one of their clarinettists) Mike Adams is a former member of Guildford Chess Club. It was good to talk to him during the interval of their most recent concert.

Returning to the Teddington Cowards, in the last few months of 1890 there was both happy and sad news for Arthur.

On 8 October he married Violet Agnes Veitch at St Alban’s Church. Randulph was there as a witness, and, of course, Francis Leith Boyd was on hand to perform the ceremony. At this point he was still, at the age of 34, just a clerk working for a music publisher in London.

Violet came from a prominent Scottish family and may or may not have been related to the endgame study composer and player Walter Veitch (1923-2004), who had a Scottish father and was at one time a member of Richmond (& Twickenham) Chess Club.

A couple of months later, his mother, Janet, died, and when the census enumerator called round the following year he found Randulph, a clerk in the Civil Service there together with his sisters Hilda, Myrrha and Ida. Arthur and Violet had bought their own place in Waldegrave Road, not very far away, and were living there with a domestic servant. Later the same year, their first child was born, a son named Russell Arthur Blackmore Coward. His third name was in honour of his godfather Richard Doddridge Blackmore, a successful novelist (Lorna Doone) and unsuccessful market gardener, who lived nearby. Blackmore was also a more than competent chess player and one can imagine that he and Arthur must have spent many evenings together over the board.

Young Russell showed promising musical talent, but tragedy would strike his family and he died at the age of only 6 in 1898.

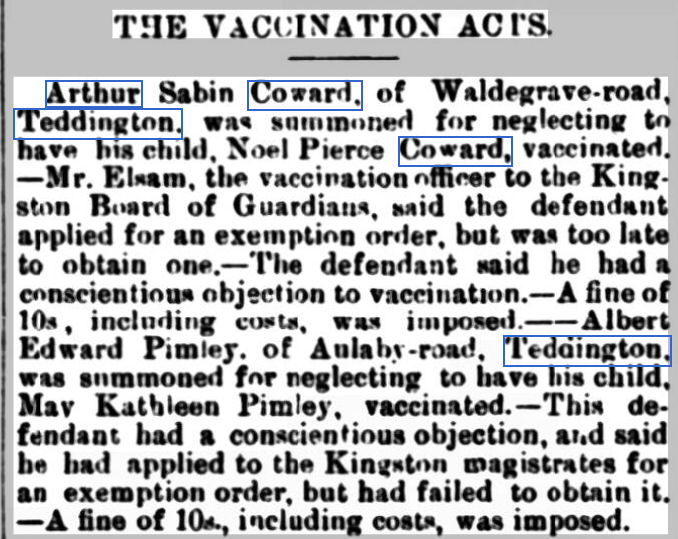

The following year another son was born, and it wasn’t long before he made the local papers.

Yes, Arthur Sabin Coward was we’d now call an anti-vaxxer, with a ‘conscientious objection to vaccination’, whatever that might mean. You might have thought that, having lost his first son, he might be only too keen to protect young Noël’s health.

And, yes, you read it correctly – or almost correctly (his middle name was Peirce, not Pierce). The Teddington Cowards were not only related to each other, but also to the great playwright, songwriter, singer and much else, the Master himself, Sir Noël Coward. Arthur was his father and Randulph his uncle.

Of course what you all really want to know is whether Noël inherited his father’s interest in chess. He’s not mentioned in The (Even More) Complete Chess Addict, but Goldenhurst, his Kent residence, had a games room with a chess table. The pieces were always set up ready for play. So perhaps he did. I’d like to think so.

The 1901 census found the family still in Waldegrave Road, and Arthur still in the same job. If you visit now, you’ll find a blue plaque on the wall (see photo above), and if you walk down the road towards Teddington, you’ll be able to meet Sampson Low, the current Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club secretary, who lives not too many doors away in the same road. Randulph, 40, still a bachelor and a clerk in the War Office, was boarding with a family named Russell (perhaps friends of the Cowards) very near St Alban’s Church.

Arthur and his family soon moved to Teddington, first to Sutton, where their third son, Eric was born, and then to a mansion flat near Battersea Park, which is where the 1911 census found him. He’d finally been promoted – to a piano salesman, a role in which he was apparently not very successful. Noël would always be embarrassed by his father’s lack of success and ambition, which may well have been caused in part by an over fondness for alcohol, a trait he shared with several of his siblings.

Randulph was a lot more successful. He finally married in 1905 and by 1911 he was a 1st class assistant accountant at the War Office, living in some luxury in St George’s Square, Pimlico. In 1920, he’d be awarded the MBE for his War Office work during the First World War.

So there you have it: one of the first Twickenham Chess Club’s leading lights was Noël Coward’s father.

Who will we discover next? Join me soon for some more 1880s Twickenham chess players.

Acknowledgements and sources:

Wikipedia

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Philip Hoare’s biography is available, in part, online here.

Various online postings by local historians.

Twickenham Museum article here.

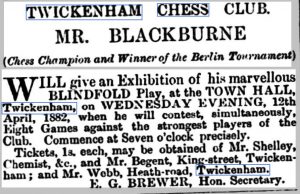

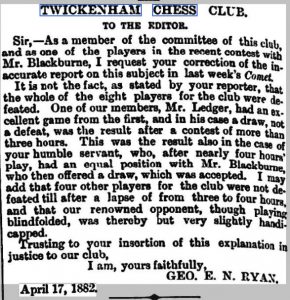

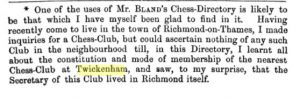

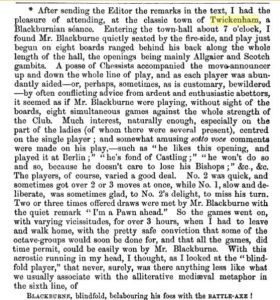

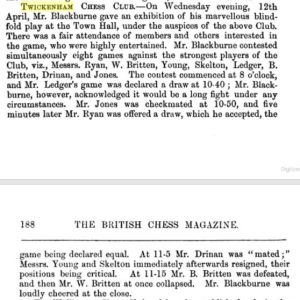

On 8 April 1882, Edward Griffith Brewer posted an advertisement in the Surrey Comet. The great Joseph Henry Blackburne was going to give a blindfold simultaneous display at Twickenham Chess Club.

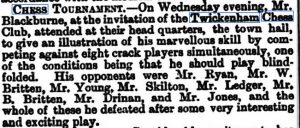

The following week, they published a report:

As local papers usually did, and still do, they got it wrong, quite apart from calling a simul a tournament. George Edward Norwood Ryan wrote in to complain.

This event even reached the pages of Volume 2 of the British Chess Magazine.

A later report followed.

We now know the names of some of the strongest members of the first Twickenham Chess Club.

You will note Mr. B. Britten and Mr. W. Britten were the last to finish. Sharing a relatively unusual surname, surely they must have been related. Perhaps they were also related to Benjamin Britten.

It’s time to have a look.

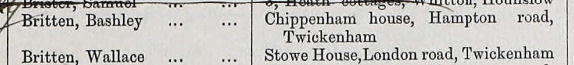

Here they are, next to each other in the 1882 London Overseer Returns, in effect an electoral roll.

Bashley and Wallace. Wallace and Bashley. Even better than Wallace and Gromit. Don’t you think everyone should call their son Bashley?

The splendidly named Bashley didn’t live in Twickenham very long. He was born in 1825 in Milton, Hampshire. He seems to have moved to Twickenham in about 1880, having previously lived in Redhill. The 1881 census found him in Twickenham with his wife Susanna, along with a cook and a housemaid, and claiming to be a Gentleman.

But he’d previously been an engineer and inventor. He was best known for Britten’s Projectile, which involved applying a coating of lead to projectiles fired from cannons, and was much used in the American Civil War. I’m not sure that his namesake Benjamin, a lifelong pacifist, would have approved. If you, on the other hand, would like to know more, you could always read his book.

This was not his only invention. Here is an improved printing telegraph, and he also took out a patent for using blast furnace slag to manufacture glass.

A few months after the Blackburne blindfold simul, Bashley went on holiday to the Scottish Highlands. On 12 August, while visiting the port of Ullapool, he died suddenly at the age of 57.

He must have been very fond of the area: if you visit there today you can find his memorial. The inscription reads: In memory of/BASHLEY BRITTEN/aged 57 years/of Twickenham, Middlesex/died at Ullapool/Augt 12th 1882.

Sadly, Bashley wasn’t able to enjoy the delights of playing chess in Twickenham very long. His namesake Wallace, however, was around rather longer.

First of all, I can find no relationship at all between Bashley and Wallace, nor to the Northampton player W E Britten, who played in the same team as William Harris and against teams including members of the Marriott family. Nor, as far as I can tell, were any of them related to Edward Benjamin Britten.

There is another connection, though, between Bashy and Wally. Bashy’s only daughter, Ada, married Algernon Frampton, who worked on the Stock Exchange, as did Wallace Britten.

We can pick him up on the 1881 census: he’s 32 years old, a clerk to a stock & share jobber, living with his wife Emily and his sister-in-law, together with a servant and a boarder. Further searching reveals that they had had two children, born in Islington in 1872 and 1874, who had both died in infancy.

By 1891 they’d moved to Rozel, 5 Strawberry Hill Road, then and now one of the most desirable streets in Twickenham. They now had a one-year-old son, Wallace Ernest, and two of his wife’s sisters were living there along with two servants. Wally was by now a Member of the Stock Exchange, so must have been doing pretty well for himself. He was still involved with Twickenham Chess Club at the time, but the last reference I can find for him is the following year. Perhaps increasing demands of work, or the desire to spend time with Wally Junior, made it harder for him to pursue his favourite game.

He’d remain at the same address for the rest of his long life. He died on 16 March 1938, and is buried in Teddington Cemetery. According to his probate record, he left £5,328 13s 5d to his son Wallace Ernest Britten, Colonel HM Army and his nephew Julius Campbell Combe, Authorised Stockbrokers Clerk. Wally Junior would eventually become a Lieutenant Colonel in the Royal Engineers, and be awarded the OBE: his son Robert Wallace Tudor Britten would also have a distinguished military career. Again, Benjamin would not have been happy.

Wallace Britten, apart from being a pretty useful club chess player, was a man who seems to have led a successful life, but one marked also by the sadness of losing his first two children. But where did he come from? He married in early 1872, but if we consult the 1871 census we might ask “Where’s Wally?”.

I eventually managed to track him down in Islington, working as a clerk and lodging with the large family of a builder named Julius Combe, a name you might recognize. His name appears to be Walter rather than Wallace, and his age seems to be 30 rather than 23. It was one of Julius’s daughters, Emily, he married the following year. I can’t as yet find him in 1861: it’s quite likely he was away at school: school pupils were often only listed by their initials in census returns. If I look for Walter, rather than Wallace, though, he’s there in 1851.

His parents, it seems, were Edwin Josiah Britten and Selina Pedder, and there he is, aged 3, living in Bloomsbury with his parents, big brothers Edwin and Alfred, and baby sister Laura. (Edwin Junior had been baptised at St Clement Danes Church by William Webb Ellis, who allegedly invented rugby by picking up a football and running with it.) Edwin senior was a Fancy Leather Worker employing two persons. Another daughter, Rachel, would be born the following year, but in October 1852 his father was admitted to the lunatic asylum at Colney Hatch, where he died in 1855. By 1861, Selina had taken over her late husband’s business as well as bringing up her children, but Wallace/Walter wasn’t there.

How did this scion of a lower middle class family end up on the Stock Exchange, playing chess and living in a substantial house in a Thames-side suburb? The answer is that we don’t know. He certainly wasn’t lacking in either ambition or ability.

His grave looks like it needs a bit of attention, but at least he has one, unlike Florence Smith, who died three years before him and lies in an unmarked grave. Her sisters and children never visited, but her grandson pauses in remembrance every time he passes by. Next time you find yourself playing chess in Twickenham, spare a thought for the Britten boys, Wallace and Bashley, two of the leading players in the early years of the first Twickenham Chess Club.

We’re going to leave Twickenham for a bit, but don’t worry. We’ll be back there soon.

I’ve received a couple of requests for information on other players, both of whom (and they had a few things in common) seemed suitable for a Minor Pieces post.

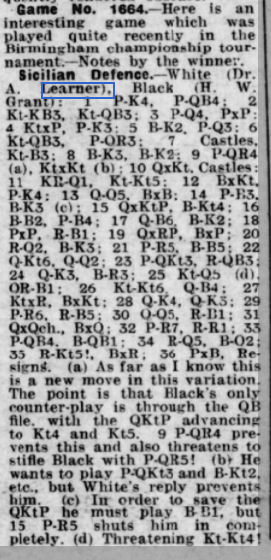

I received an email the other day from my friend Ken Norman, who had come across some games from a Dr A Learner, who was active in Sussex chess in the 1960s, in an old copy of CHESS and, perhaps intrigued by the name, wondered if I could provide any more information. He also contacted Brian Denman, who knows almost all there is to know about Sussex chess history. Brian provided Ken with a games file which he was happy for Ken to share with me.

He seems to have been an interesting man who led an interesting life.

He was Dr Abraham Emanuel Learner, although he didn’t very often use his middle name and seems to have been known to his family and friends as Bill. He was born in London on 13 December 1904 and died in Eastbourne, Sussex on 16 February 1983. Some records spell the family name ‘Lerner’.

We can pick the family up in the 1911 census. His father, Arnold, was described as an ‘incandescent and clothing dealer’, born in Russian Poland, as was his mother, Deby, a dressmaker. Arnold and Deby married in the East London Synagogue in Mile End, right at the heart of the Jewish community, on 15 October 1904, only two months before Abraham was born. Another son, Mark, arrived in 1906. Soon afterwards they left London for Gateshead, in the north east of England, where they welcomed two daughters, Goldie and Sophie. It seems that all four siblings married outside the Jewish faith, and all of them emigrated to Australia, although Abraham, or Bill as we should perhaps call him, later returned to his home country.

Bill studied chemistry at Birmingham University, eventually earning a doctorate. During his post-graduate or perhaps post-doctoral work between 1927 and 1928 he wrote three papers on the structure of fructose and inulin along with Norman Haworth, who would win the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1937, and, in two cases also with Edmund Hirst. I tried reading the papers but failed to get beyond the first paragraphs. If you want more information I’d suggest you contact my BCN colleague Dr John Upham, who knows all about this sort of thing.

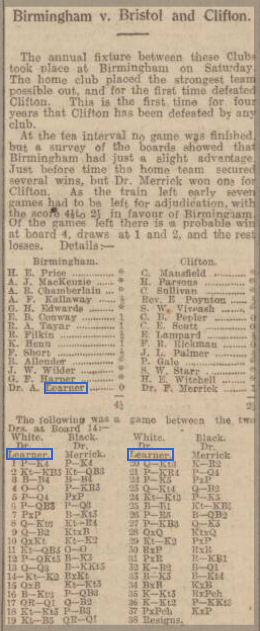

We first pick him up as a chess player in 1929. Here he is, playing on bottom board in a match between Birmingham and Bristol & Clifton, who fielded the great problemist Comins Mansfield on top board.

His loss against another doctor doesn’t appear in Brian’s games collection.

At about the same time he took part in a blindfold simul against George Koltanowski, winning with an attractive rook sacrifice. Kolty resigned, ‘seeing’ that a zigzag manoeuvre by the black queen would lead to a swift checkmate.

In 1933 Bill Learner married Elsie Harris in Birmingham. They would have just one son, named Arnold after his grandfather, who would predecease him.

During the 1930s Dr Learner continued to play for Birmingham, and for Worcestershire in county matches. In 1934, playing for his county against Oxfordshire, he was paired against another future Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Professor Robert Robinson, but lost that game. (Other chess playing, Nobel Prize winning chemists include Frederick Soddy and John Cornforth – might be worth a Minor Pieces series at some point.)

In this spectacular win Dr Learner played a dangerous gambit, offered a passive bishop sacrifice and finally gave up his queen for an Arabian Mate. But Black had a chance to turn the tables. After 17. Rae1? (the immediate Rf3 was winning) Qxc2, the second player has a winning advantage. A game well worth your time analysing, I think.

We can see from these examples that Bill Learner was a sharp tactician.

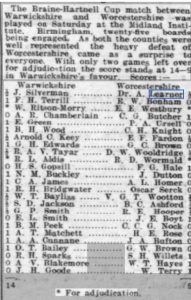

By 1935 he was on top board for Worcestershire. A county match against Warwickshire saw him up against another interesting opponent, future MP Julius Silverman. The result of this game was a draw. You’ll see a number of interesting names in both teams.

In a match against Leicestershire, his Stonewall Dutch scored a rather fortunate victory against Alfred Lenton (from whom you’ll hear a lot in future Minor Pieces) when his opponent, who shared 3rd place in the 1935 British Championship and 2nd place the following year, blundered in a winning position.

In 1937 Learner found himself on the wrong side of the law, being fined 10s for a speeding offence. I guess that’s what happens if you’re A Learner, driver. His address was given as Elmdon Avenue, Marston Green, Birmingham, very near Birmingham Airport.

Bill Learner won the Birmingham Post Cup in 1938, but when given the chance to prove himself at a higher level, in an international tournament organised by Ritson Morry the following year, he finished in last place. A dangerous attacking player, then, but perhaps not quite able (or ready) to compete against masters. By now, as you’ve probably worked out, World War 2 was about to break out, and that put his chess activities on hold.

The 1939 Register saw him at the same address, although Elmdon Avenue has become Elmdon Lane. (It appears to be Elmdon Road now.) He is a Managing Director, possibly of a paint factory. (The second line is not fully legible but we know, from his mother’s probate record, that he was a paint manufacturer. I guess the chemistry background would have come in useful.) Elsie and Arnold aren’t there: they’re up in the village of Ponteland, north west of Newcastle, staying with his sister Goldie and her family. Presumably they considered it safer there than in Birmingham. Bill had shown his love of the area by naming his house Ponteland.

He turned out for a club match in 1940, but then nothing until 1945, when chess resumed after the war, and he resumed where he left off, playing for Birmingham and Worcestershire.

Here he is providing brief annotations for a win against an opponent I assume to be the problemist Herbert W Grant.

Then, at some point he emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, where he took part in the 1948-49 championship. He finished 13th out of 14 on 4½ points (Cecil Purdy was the winner) but did manage to defeat Maurice Goldstein, who blundered into a mate when he could have traded off into a winning ending.

By 1952 he was Vice-President of Melbourne Chess Club and wrote a long (but not especially interesting) article about the delights of his favourite game.

What was he doing in Melbourne when he wasn’t playing chess? In the 1949 and 1954 electoral rolls he was a manufacturer, in 1958 and 1963 a director. Was he still manufacturing paint? Perhaps he was working with his brother: Mark owned a large textile importing warehouse right in the city centre.

He continued to be active in Melbourne chess until 1963, when he decided to return to England for his retirement, settling on the south coast and soon getting involved in Sussex chess. Playing at Bognor Regis in 1964 he came up against a man who would, the following year, become Yugoslav champion and an International Master. Here’s what happened.

A pretty effective demolition of a strong opponent, I’d say.

Dr Learner had a habit of winning extremely short games. Here are two examples.

He continued playing chess until at least 1970 before deciding to hang up his pawns. The last game we have available is a draw against Brian Denman from a match between Hastings and Brighton. His 1970 grade was 191, down from 195 in 1969 and 201 in 1968, with his clubs given as Hastings and Eastbourne.

His address at his death (just three months after his wife) was given as High Bank, Borough Lane, Eastbourne, and his probate record tells us his estate was worth £102,858. He’d done pretty well for himself, in business as well as in chess.

Dr Abraham Learner was a strong county player, a dangerous tactician who, on a good day, could beat master standard opponents.

His career of more than four decades can, like Caesar’s Gaul, be divided into three parts: in Birmingham from the late 1920s to the late 1940s, in Melbourne until the early 1960s and finally in Sussex.

Players like him are the backbone of club and county chess.

My thanks to Ken for his interest in Dr Learner and to Brian for providing the game scores. If there are any other British chess players you’d like me to investigate do get in touch.

Other sources consulted:

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.findmypast.co.uk

www.newspapers.com

BritBase

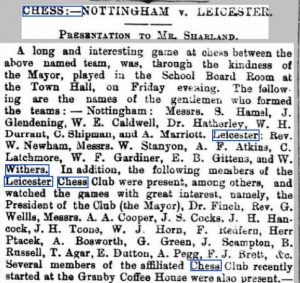

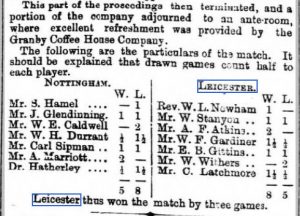

Continuing my series about Arthur Towle Marriott’s Leicester opponents, we reach W Withers, almost certainly William. Apologies to those of you who’ve been eagerly awaiting this article, but I’ve been busy on other projects. You’ll find out more later.

Great song, and I hope you all have a lovely day, but this wasn’t William Harrison Withers Jr.

W Withers, sometimes WJ Withers (or were they two different people?), first appeared in Leicester chess records in 1874, when he was elected Club Secretary, and continued his involvement, representing Leicester, and the smaller club, Granby, in matches against other Midlands towns and cities, until 1900. But who was he?

Withers is a surprisingly common name in the East Midlands. One of James Towle’s fellow Luddites bore the name William Withers, but his family were from Nottingham rather than Leicester and seem not to have been related to the chess player.

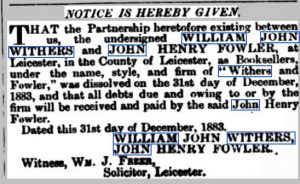

There were several gentlemen named William Withers in Leicester at the time. We can assume, because, as a young man he was the club secretary, that he came from an educated background. The only W Withers who fits the bill is William John Withers, who lived most of his life in Leicester, although his birth was registered in the St Pancras district of London in the second quarter of 1853, and who died in the Harrow/Hendon area on 23 December 1934.

William’s father, George Henry Withers, was the son of John Withers, born in the chess town of Hastings. John had a varied career. Originally a lace maker, he joined the police, rising to the rank of inspector. He then went to work on the railways, first as a station master, and then as a railroad contractor, before becoming a commission agent, and, finally, a clerk at a coal wharf. Was there any job he couldn’t turn his hand to? In between times, he found time to father eight children: seven sons and a daughter. Not for the first time in Minor Pieces, his seventh son was named Septimus.

George Henry Withers was John’s eldest son. Born in about 1830, he followed his father into the railways, a very common occupation at the time. When he married Mary Ann Caunt in 1849, he was a railway clerk, living in the Leicestershire town of Melton Mowbray, famous for its pork pies. He was described as being ‘of full age’: it’s not certain that this was true. By the 1851 census he was a station master living in Orston, Nottinghamshire.

This was presumably Elton Station, now called Elton and Orston, half way between those two villages, which had only opened to passenger traffic the previous year. In 2019/20, it was the second least used station in the country.