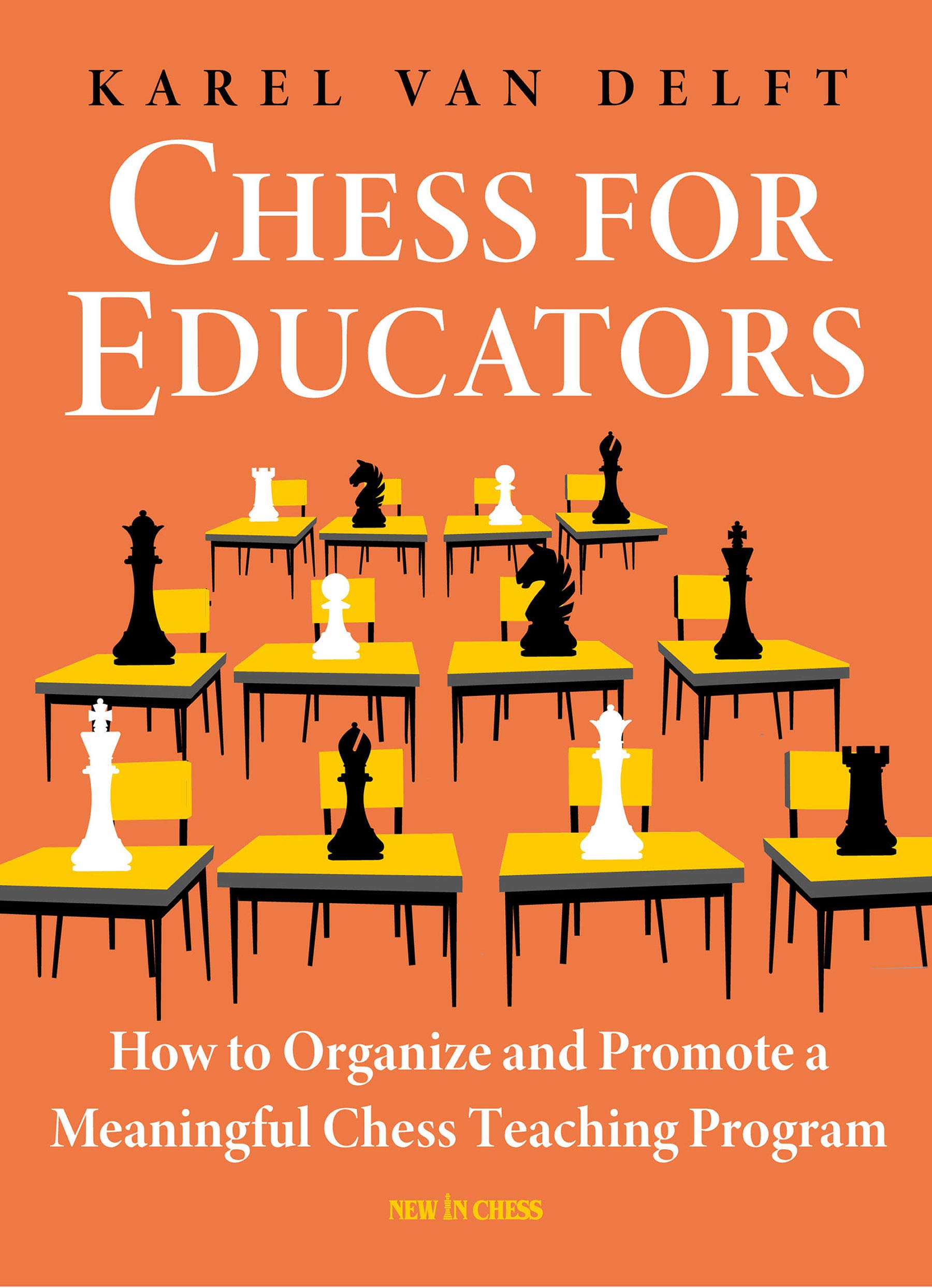

From the publisher:

“Every chess player wants to improve, but many, if not most, lack the tools or the discipline to study in a structured and effective way. With so much material on offer, the eternal question is: “”How can I study chess without wasting my time and energy?””

Davorin Kuljasevic provides the full and ultimate answer, as he presents a structured study approach that has long-term improvement value. He explains how to study and what to study, offers specific advice for the various stages of the game and points out how to integrate all elements in an actionable study plan. How do you optimize your learning process? How do you develop good study habits and get rid of useless ones? What study resources are appropriate for players of different levels? Many self-improvement guides are essentially little more than a collection of exercises.

Davorin Kuljasevic reflects on learning techniques and priorities in a fundamental way. And although this is not an exercise book, it is full of instructive examples looked at from unusual angles. To provide a solid self-study framework, Kuljasevic categorizes lots of important aspects of chess study in a guide that is rich in illustrative tables, figures and bullet points. Anyone, from casual player to chess professional, will take away a multitude of original learning methods and valuable practical improvement ideas.”

“Davorin Kuljasevic is an International Grandmaster born in Croatia. He graduated from Texas Tech University and played in USCL 2007 and 2008 for Dallas Destiny, the team that became US champion in both these years. He is an experienced coach and a winner of many tournaments.”

‘Study’ is the operative word here.

When I was learning chess in the 1960s and playing fairly seriously in the 1970s, chess wasn’t something you studied unless you were a top grandmaster. I’d play in club matches and tournaments. I’d read books and magazines because I enjoyed reading them, and, if I learnt something as well then so much the better. It wasn’t anything resembling serious study as you might study a subject at university. In those days, of course, you didn’t have a lot of opportunity to do much else.

In those days we couldn’t have imagined having a multi-million game database and a computer program capable of playing far better than any human on our desk, or being able to play a game at any time against opponents from anywhere in the world.

It’s not surprising, then, that ambitious players at any level are, if they have the time, keen to raise their rating by studying chess seriously.

We also know a lot more than we did, even 20 or 30 years ago, about the teaching and learning processes: lessons that can be applied to chess just as they can to other domains.

In the past, chess books told you what you should learn. Now, we’re seeing books, like this one, that teach you HOW you should learn. There’s a big difference.

Let’s start, controversially, at the end.

Chapter 9: Get organized – create a study plan

The author advises us to create a weekly timetable. Table 9.1 is based on the assumption that you’re at school in the morning, when you can spend 3 hours every afternoon and 2 hours every evening studying chess.

In my part of the world, if you’re an older teen you’re probably going to be at school in the afternoon as well as the morning, and have three hours of homework to do when you get home. Not to mention family commitments, other interests, hanging out with friends, eating, sleeping… I wonder how many chess players actually have time to study 4-5 hours a day, or even 1-2 hours a day, on a regular basis. On the other hand, 12-year-old Abhi Mishra, who has just become the youngest ever Grandmaster, spends at least 12 hours a day studying chess.

Returning to the Preface, the author anticipates your question: who will benefit the most from this book? “In my view, it would be self-motivated players of any level and age who are serious and disciplined about their chess study and have enough time to put the methods from the book into practice.”

If you fall into this category, read on. Even if you don’t: if you only have an hour or two a week to study, rather than 4-5 hours a day, you might still learn a lot.

What we have is 9 chapters looking at different aspects of studying chess, each concluding with a helpful list of bullet points. It’s not just a book of technical advise on how to study, though. There’s a lot of chess in there as well, mostly taken from games you probably won’t have seen before. The first eight chapters have, as is the case with many books from this publisher, some exercises for you to solve, based on the most interesting positions from the chapter. The tactics and middle-game chapters also have questions for you to answer: do they tally with the author’s solutions given in Chapter 10?

In Chapter 1, the author asks “Do you study with the right mindset?”. Now, he doesn’t mean mindset in this sense, although that will come in useful. Instead, he suggests that mastering chess requires both time and intelligent study. There’s no substitute for study time. He quotes the example of English GM Jonathan Hawkins, only an average club player at 18, but through hard work, much of which involved with studying endings, became a GM by the age of 31.

A proper chess study mindset means, in Alekhine’s words, ‘a higher goal than a one-moment satisfaction’. Four typical mistakes are: lack of objectivity, shallow study approach, short-run outlook and playing too much. Kuljasevic talks about the correct balance between playing and studying. He quotes Botvinnik as saying that chess cannot be taught, only learned, which he interprets as meaning that everyone learns in a different way, and that it’s you, rather than your coach, who will make yourself a stronger player.

Kuljasevic was shocked to read a well known GM’s coaching advert: “I have produced numerous top-level players”. “Excuse me, but chess players are not ‘produced’! Every chess player’s learning process is their unique experience that cannot be replicated on someone else.”

These days there are many study methods available, and Chapter 2 provides a guide to fifteen you might consider, and giving them all scores out of 5 for practical relevance, study intensity and long-term learning potential. The three methods which score a maximum of three fives are Deep Analysis, Simulation (pretending to play a real game by guessing the next move) and Sparring (playing a pre-arranged game or match with a training partner for a specific reason).

As an example of what is meant by Deep Analysis, this is Aronian – Anand (Zurich 2014) with Black to play. Anand played 58… Ke7 here, but Re1+ would have been a more stubborn defence. Kuljasevic wanted to prove that White can always win positions of this type, and here spends seven pages doing just that.

Of course such an approach won’t suit everyone, but this chapter will help all readers determine the most useful methods for them. The point is not so much the relevance or otherwise of this particular ending, but the process itself used to analyse it.

Chapter 3 is about identifying your study priorities. At this point the author divides his readership into five categories:

- Intermediate player (1500-1800 Elo)

- Advanced player (1800-2100 Elo)

- Improving youngster (1900-2200 Elo)

- Master-level player (2100-2400 Elo)

- Strong titled player (2400+ Elo)

He suggests that, in general, you should spend 10% of your time on openings, 25% on tactics 25% on endgames, 20% on middlegames and 20% on general improvement. What proportion of your study time do you spend on openings? I thought so!

He then makes suggestions about how readers in each category might prioritise their studies.

If you’re an intermediate player you should concentrate on improving your tactical and endgame skills, while choosing a simple opening repertoire. Once you reach 1800 strength you can start working on more strategically complex openings. Club standard players should spend a large proportion of their time studying endings (Jonathan Hawkins would agree, as would Keith Arkell) and players of all levels would benefit from solving endgame studies on a regular basis.

Chapter 4 is about choosing the right resources for your study plan. Here we have a list of online resources: chess websites, the categories for which they are suitable, and, in each cases, the specific study opportunities they offer. Then we look at the best websites for each of the study methods from Chapter 2. An extensive list of recommended books for each of the five categories of player from Chapter 3 follows, arranged by subject matter. The books include classics by authors such as Alekhine, Spielmann and Chernev as well as more recent books. GM Grivas is quoted: “Reading the autobiographical games collections of great past players is like taking lessons with some of the greatest players in history”. Unlike Kuljasevic, I’m not convinced that Chernev’s Logical Chess, excellent though it is for novices, is suitable for anyone much over 1800, though. There’s also some very useful advice on the best way to use ChessBase and other database software.

Chapters 5 to 8 each focus on one specific aspect of chess: openings, tactics, endings and middlegames.

Chapter 5 tells you how to study your openings deeply. The author starts with a warning: “I have met many people, and I’m sure you have, too, who have fallen into the trap of spending too much time studying openings. If they were to study other aspects of the game as zealously as openings, I am sure that they would be more complete, creative, and, most likely, stronger chess players. Young players and their coaches should especially keep this in mind.” He quotes, with approval, Portisch’s opinion: “Your only task in the opening is to reach a playable middle game”, and advises simplicity and economy when deciding on your openings. The study material in this chapter, then, is more suited for master level players and above.

This, for example, is an example of a ‘static tabiya’: you may well recognise it as coming from the Breyer Variation of the Ruy Lopez.

“This is one of the most well-known opening tabiyas, not only in the Ruy Lopez, but in chess in general. Over 1000 tournament games have been played from this position, from the club to the super-GM level. There is something appealing about this static type of structure for both sides as it contains a lot of potential for creative strategic play. I would like to present my brief analysis of a fairly rare idea: 17. Be3!?”

17. Bg5 is usually played here, meeting 17… h6 with Be3, happy to spend a move weakening the black king’s defences. Be3 has a different attacking plan in mind: Nf3-h2-g4-h6+ and possibly also Qf3. This is discussed over 3½ pages: I think you have to be a very stong player with a lot of study time available to go into this sort of detail, though.

Chapter 6 advises you to ‘Dynamize’ your tactical training. We’re all used to solving puzzles where we play combinations to win material or checkmate the enemy king. We could do more than that, though, by studying dynamic positions, complicated, double-edged tactical positions and positional sacrifices. We can also improve our tactical imagination by solving endgame studies and problems.

At the end of this chapter we get the chance to take a tactics test: “20 exercises consisting of tactical puzzles, positions for analysis, endgame studies, and problems for the development of dynamics and imagination”.

It’s Black’s move in this tactical puzzle. Your challenge is to solve it blindfold.

This is taken from Xie Jun – Galliamova (Women’s World Championship 1999). Black played 30… Qc7 here and eventually lost. She should have preferred 30… Qc8! (Nd2+ also wins) 31. Rc1 Qg4!, an attractive geometric motif winning either rook or queen.

Here, by contrast, is an endgame study, composed by FK Amelung in 1907. It’s White to play and win. Again, you’re challenged to solve it without moving the pieces.

The solution is 1. Rd8+ Ke1 2. Re8+ Kd2 3. Nc3! c1Q+ 4. Nb1+ Kd1 5. Rd8+ Ke1 6. Rf8! and wins.

There’s a lot more to tactics training than sac, sac, mate!

Studying endings can seem rather dull, so it’s good to know that Chapter 7 tells you how to make your endgame study more enjoyable. Kuljasevic advises that, instead of reading books from beginning to end you look at practical examples, including your own games, and, (yes, again) endgame studies. He agrees with Capablanca that “Study of chess should commence with the third and final phase of a chess game, the endgame”.

Chapter 8 is all about strategy: how to systemize your middlegame knowledge. This is the hardest aspect of chess to study. The author looks at studying the pawn structures that might arise from your opening repertoire in a systematic way, and then goes on to discuss piece exchanges: understanding when exchanges might be favourable or unfavourable rather than just seeing them as a way to simplify towards an ending.

The chapter concludes with a short quiz on this subject. Here’s the first question: would you advise White to trade rooks, to give Black the option of trading, or to move his rook away?

This was Mamedyarov – Carlsen Baku 2008

White correctly moved his rook away, playing 25. Rf1, and later won after a Carlsen blunder. The coming kingside attack will be much stronger with the rook on the board, and Black can do nothing on the c-file.

Chapter 9, as we’ve seen, looks at how you might devise your own study plan – on the assumption that you have several hours a day to study, and Chapter 10 provides solutions to the quiz questions.

So, what to make of all this? I found it an extremely impressive book on an increasingly important aspect of chess: ‘how to learn’ as opposed to ‘what to learn’. Davorin Kuljasevic has clearly put an enormous amount of thought and hard work into writing it. If you’re within the target market – you want to improve your chess and have a lot of time available for that purpose – I’d give this book a very strong recommendation.

Even if you only have a few hours (or even less) a week, rather than a few hours a day to set aside for chess study, you’re sure to find much invaluable advice about how to make the most of your time.

There’s a lot of great – and highly instructive – chess in the book as well, so you might enjoy it for that alone. Much of it, though, I felt, was aimed more at the higher end of the rating scale. It would also be good to read a book on how to study chess written more for average players with limited study time.

Kuljasevic’s previous book (there’s an excellent review here) was shortlisted for FIDE’s 2020 Book of the Year, and I wouldn’t be surprised if this book was similarly honoured. He’s clearly an exceptional writer as well as an exceptional coach.

Richard James, Twickenham 22nd July 2021

Book Details :

- Softcover: 384 pages

- Publisher: New in Chess (1 May 2021)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9056919318

- ISBN-13:978-9056919313

- Product Dimensions: 17.27 x 2.54 x 23.62 cm

Official web site of New in Chess

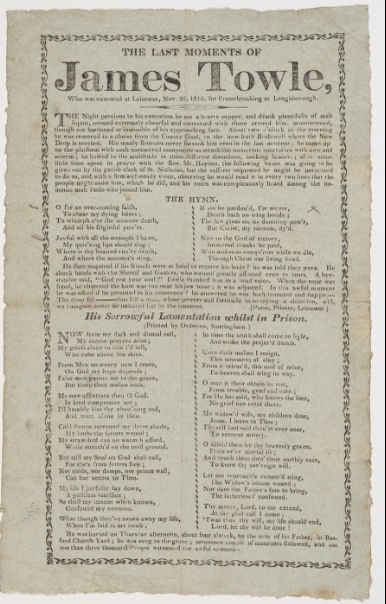

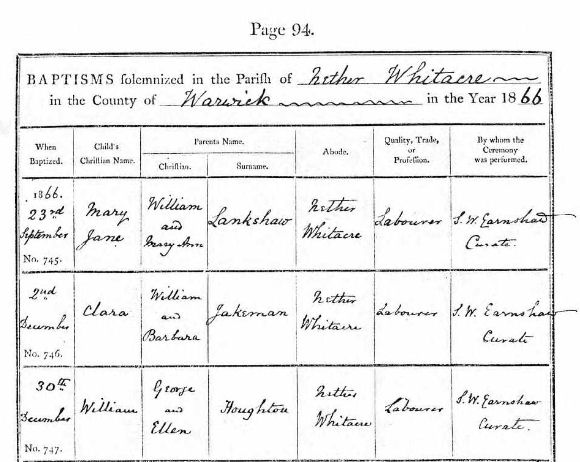

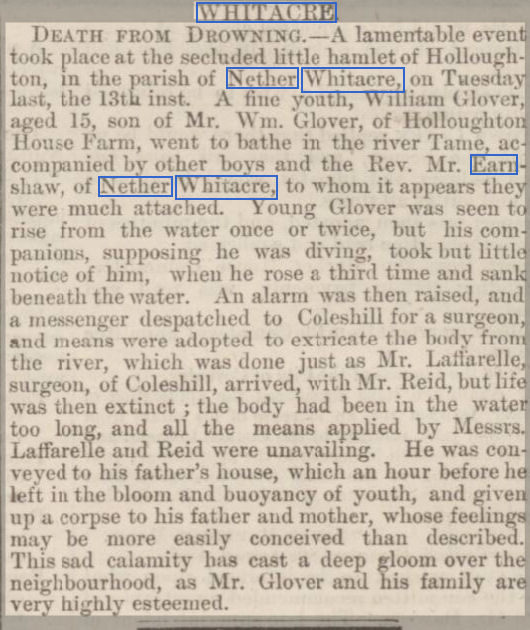

Let me take you back to the church of St Giles, Nether Whitacre, on 30 December 1866. The foundation dates back to Norman times, but by then it may have been in a state of disrepair, as it would be rebuilt in 1870, not long after Samuel Earnshaw’s departure.

Let me take you back to the church of St Giles, Nether Whitacre, on 30 December 1866. The foundation dates back to Norman times, but by then it may have been in a state of disrepair, as it would be rebuilt in 1870, not long after Samuel Earnshaw’s departure.