For a few years in the mid 1930s a remarkable story was playing out in Leicestershire chess. The boys from Desford Approved School, who had been sent there from all over the country having fallen foul of the law, were taking part in the Under 16 section of the county chess championship, dominating the event, winning game after game against their law-abiding contemporaries, and even beating adult teams in the county league.

I wanted to find out more about the lives of some of the Desford boys (the titular Eric was their star player), and about the men who chose to promote chess as an activity for these boys from troubled backgrounds. This article looks mainly at the latter: a future article will consider the former.

First, a bit of history. The Leicester Industrial School for Boys, Desford opened in January 1881. Boys were sent there for all sorts of reasons: some had been in trouble, some were destitute and wandering the streets, some were living in brothels, some were sent there by their parents because they were out of control at home. While there they would be subject to strict discipline as well as learning a trade to help them find employment on their release.

One such boy, beyond his father’s control, was Tom Harry James, who was there from January 1904, when he was 12 years old, until October 1907. His father was expected to pay his expenses, but seemed reluctant to do so.

The young miscreant would live a long and colourful life, dying in Yakima, Washington in 1980, but that’s a story for another time and place. How do I know this? Tom Harry James was one of my father’s half brothers. Tom Harry senior and his first wife had twelve children, and after she died he remarried, producing another six children. My father, Howard James, the youngest of them, was born in 1919.

It was now January 1917, and time for a new chairman to be appointed to Desford Industrial School. The man elected was Sydney Ansell Gimson (it’s pronounced Jimson), a local councillor representing the Liberal Party and a member of a prominent Leicester family.

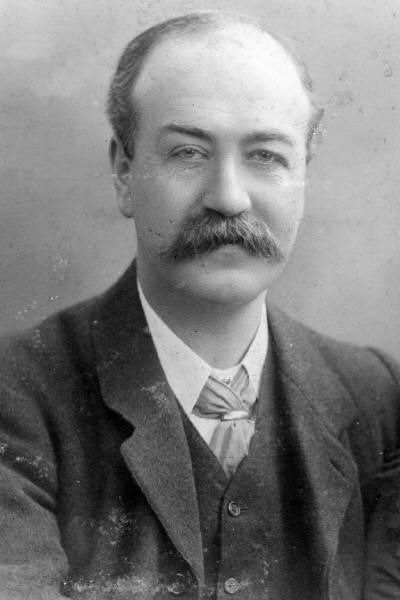

In 1842, Josiah Gimson and his brother Benjamin started an engineering firm in Leicester. Josiah was a man of progressive views: a supporter of Robert Owen‘s socialist ideas and a secularist, founding the Leicester Secular Society, which is still active today. Sydney, born in 1860, was the oldest son of Josiah’s second marriage, and, although he was also sympathetic towards his mother’s unitarian views, played an important role in the Secular Society. At first, he was anti-union, however, being more interested in the concept of the individual, but seems to have changed his opinion later in life. He worked for some time in the family business, but, not needing the money, retired early in order to devote the remainder of his life to public service.

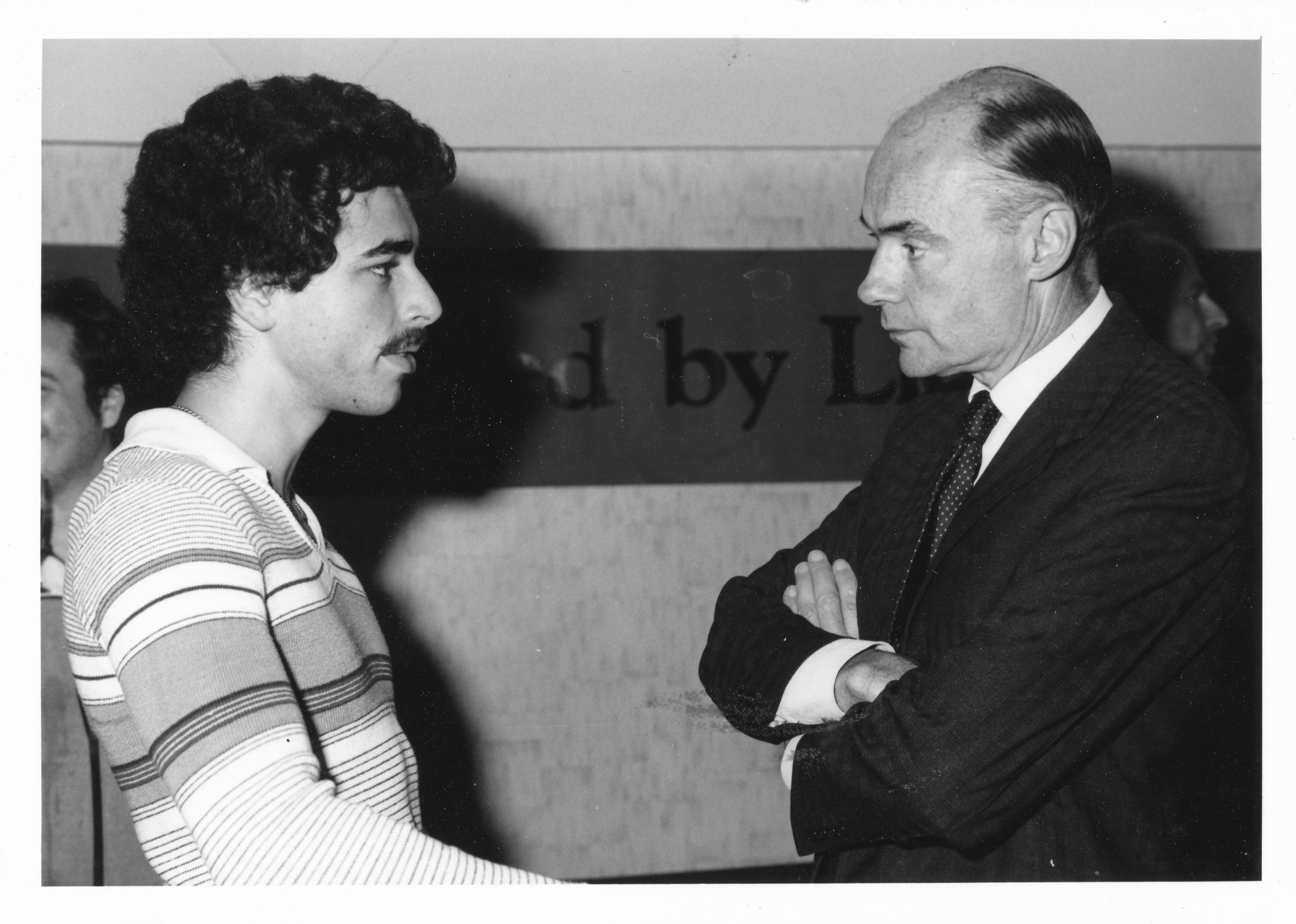

Here’s Sydney, photographed in 1904.

You can read more about both Josiah and Sydney in Ned Newitt’s Who’s Who of Radical Leicester here, and about the family business here (Wiki) and here (Story of Leicester).

Some of his brothers were also of interest. His older half-brother, Josiah Mentor Gimson, also worked for his father. One of JM Gimson’s sons, Christopher, played first class cricket for Cambridge University in 1908, and again for Leicestershire in 1921 when on extended leave from the Indian Civil Service. His 1975 obituary in Wisden described him as ‘an attacking batsman and a fine outfield’. Another of his sons, David, was the first chairman of the Leicestershire Contract Bridge Association on its formation in 1946. A competition for a trophy bearing his name was competed for at least up to 2019.

The most important member of the family, though, was Sydney’s younger brother Ernest William Gimson. Ernest met William Morris at the Secular Society, and soon joined forces with him, working as a furniture designer and architect, being very much involved in the Arts and Crafts movement. If you’re interested in this sort of thing, you’ll find a lot more of interest via your favourite search engine. If you’ve got £50 to spare you could also buy this book.

The Leicester Secular Society has a feature on the Gimson family here. You might want to follow some of their other links and look around other pages of their website.

Meanwhile, back at Desford Industrial School it was now 1921. There was a vacancy for a new Superintendent. Sydney wanted someone who shared his progressive views on education: the right man for the job was 31 year old Cecil John Wagstaff Lane, the son of a farmer and innkeeper from Melton Mowbray, who was already working there as the Chief Assistant. The 1921 census found him settled in with his wife Dora and daughter Joan, along with other staff members and more than 200 boys from all over the country. As well as boys from Leicester, many of them were from other parts of the Midlands, London and Yorkshire, especially Hull. By now they would have been sent there by magistrates who would decide to which institution the young offenders up before them should be sent.

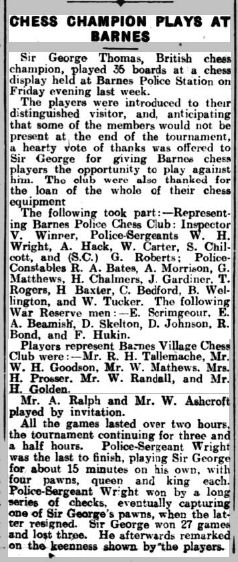

Sydney was very much in the ‘nurture’ camp, believing that most of the young offenders were victims of family circumstances, and, if they were treated well, would grow up to lead useful lives and become law-abiding members of society. He found an ally in Cecil Lane, and, despite the 30 year gap in their ages, the two men became firm friends. Cecil introduced a less punitive regime, running Desford along the lines of an English Public School. There were four houses: Red, White, Blue and Green, each with a house master who acted as a surrogate father to the boys. Much emphasis was placed on sport, with regular visits from top class players and competitions against other schools in the area. The most popular sport there was boxing: the school’s annual boxing competition, held over the New Year period, became a big local event, attended enthusiastically by the great and good of Leicester society.

Looking at the newspaper sports columns in the inter-war years it’s notable how popular boxing was, and also how often the professionals fought.

If boxing was the Desford boys’ favourite sport, the other sport which played a very big part in their lives was, perhaps unexpectedly, chess. Cecil Lane and Sydney Gimson don’t appear to have been competitive players themselves, but it’s clear they both enjoyed the game and had the foresight to realise how much it could benefit the boys in their care.

You might think they missed a trick by failing to invent chessboxing, but that’s something we’ll leave aside for now.

By 1925 word was going round that chess was becoming popular within the school.

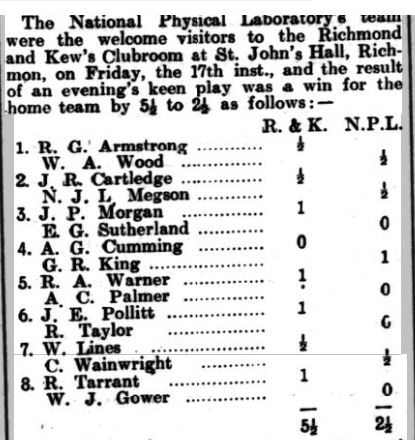

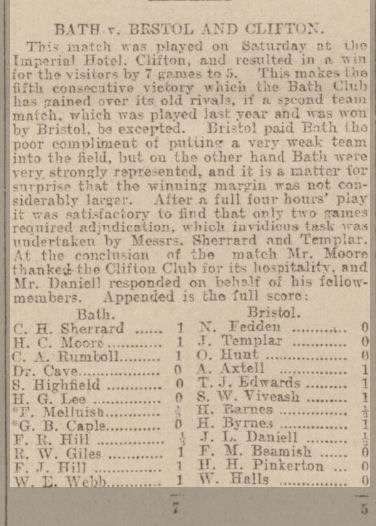

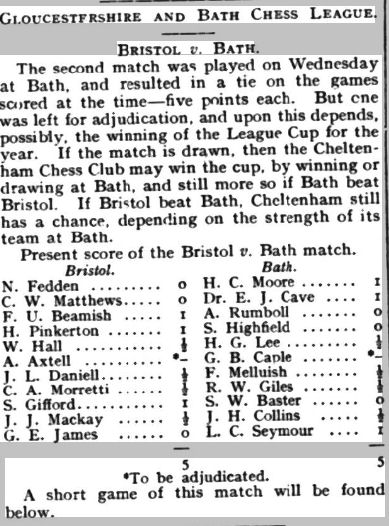

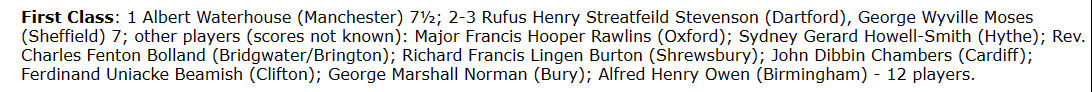

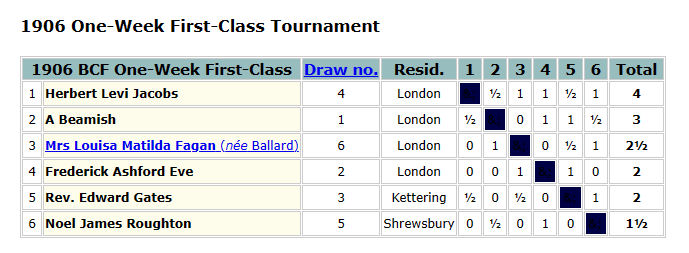

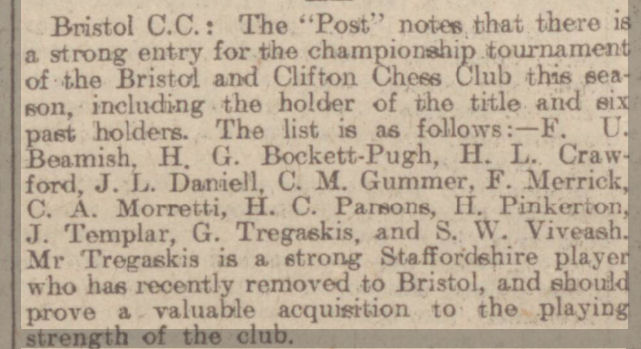

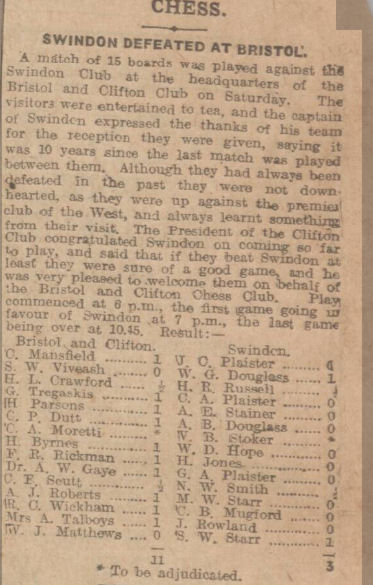

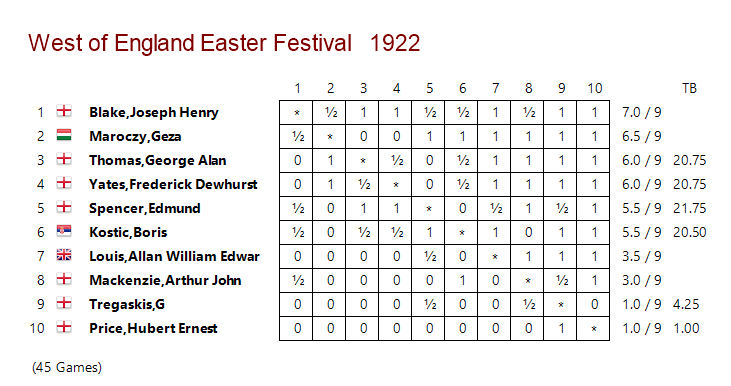

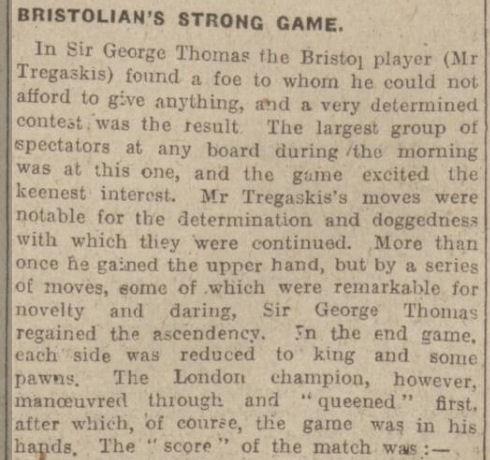

Gimson and Lane might not have been club players (and here’s Sydney losing to one of his pupils), but they knew someone who was. Councillor Frederick Chappin, a member of the Conservative Party, was a political opponent of Sydney Gimson, but a friend who not only shared his interest but had been a competitive player in the county league going right back to the 1880s, on at least one occasion playing on board 2 behind none other than the great Henry Ernest Atkins.

By 1927 the boys needed more demanding opposition and county champion Victor Hextall Lovell, Leicester’s strongest player at the time (you’ll meet him in a future Minor Piece) was invited to give a simultaneous display. Lovell’s father was a former Mayor of Leicester and, like Frederick Chappin, a Conservative Councillor.

Lovell returned during the 1929-30 Christmas holidays, and was emphatic that the standard of play had improved since his previous visit.

Desford School celebrated its jubilee in 1931, and this article outlines some of the changes Lane had made since his appointment as Superintendent.

The 1933 Children and Young Persons Act renamed Industrial Schools as Approved Schools, so Desford was now Desford Approved School. However, the school always preferred to be referred to locally simply as Desford School or Desford Boys’ School to avoid stigmatising the pupils. At this point children could remain there until the age of 16.

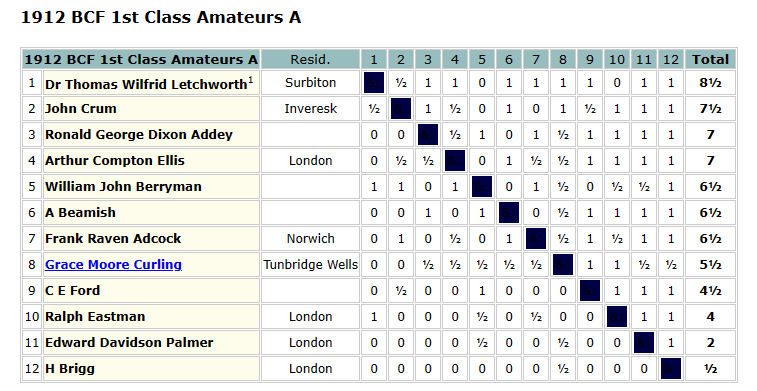

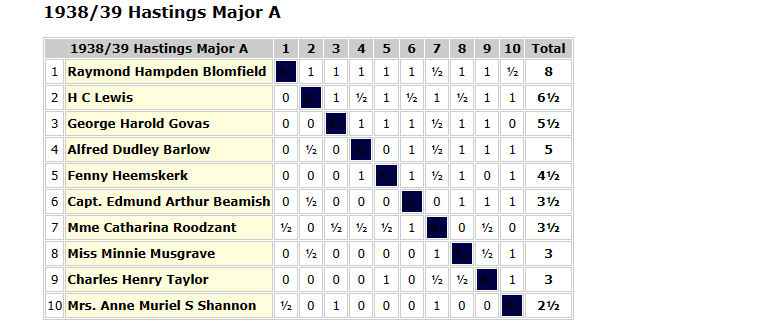

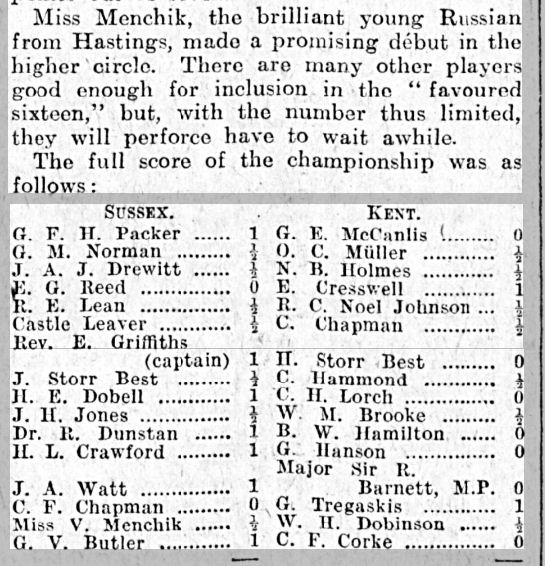

As you saw last time, Leicester was a pioneer in junior chess, amongst many other things. In January the first county boys’ championship took place in two sections, which appeared to be Under 18 and Under 16. The Desford boys were keen to take part, six entering in the senior and six in the junior section. Other schools represented were Wyggeston, for many years Leicester’s leading academic secondary school, Alderman Newton, also classified as a ‘Public School’ at the time, City Boys and Moat Road.

Unfortunately it’s not possible to identify all the Desford chess players as only initials and surname were given in the local press. In some cases the boys also took part in the annual boxing tournament, where the press gave their full names. Although the Leicestershire Records Office holds admission records, they are not able to release them due to data protection legislation, and, as we’ve seen, the boys might have come from anywhere in the country. Having an unusual surname was of course helpful.

As you’ll see, the Desford boys were pretty successful in their first competitive outing.

On a sad note, the winner of the senior section, Keith Dear, died four years later at the age of just 20.

There, winning the junior section and representing Desford (Approved) School, was Eric Harold Patrick, whose life we can reconstruct, although we don’t know why he was there.

He had been born on 23 August 1921 in Cannock, Staffordshire, the oldest of five children of Harold and Lily Patrick, who had married that January when they were both only 19. Shortly after his birth the family moved to Leicester, Lily’s home town. At the time of his success, then, he was only 12 years old, competing against boys who were a year or two older than him, and attending the city’s most prestigious secondary schools.

When Sydney Gimson came to present his annual report to the education committee a few months later, young Eric’s chess success was the item which elicited the most interest.

Gimson also revealed that he had played two games against Eric, both players winning one game.

There was another administrative change. From now on, boys had to leave Desford at 15 rather than 16. Sydney wasn’t impressed, as he told the school prizegiving. For some reason this was reported in the Women’s column of the local paper.

You’ll see that the school only awarded four prizes – and the fewer prizes you award, the more they’ll be valued. The most public spirited boy, the boy who was best at sports, the captain of the winning house – and the best chess player. A demonstration, I think, of the respect in which chess was held at Desford at the time.

By the end of the year it was time for the 1935 edition of the county junior championship. As boys now left Desford at 15 they were only represented in the junior section.

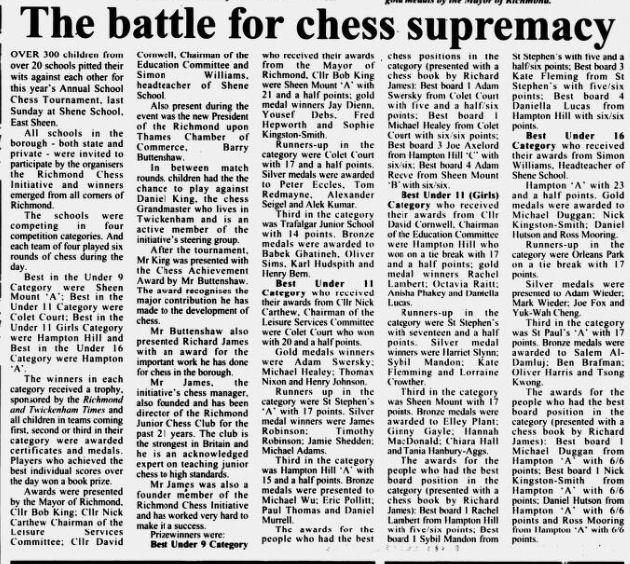

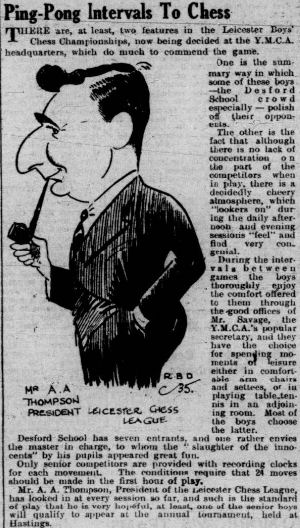

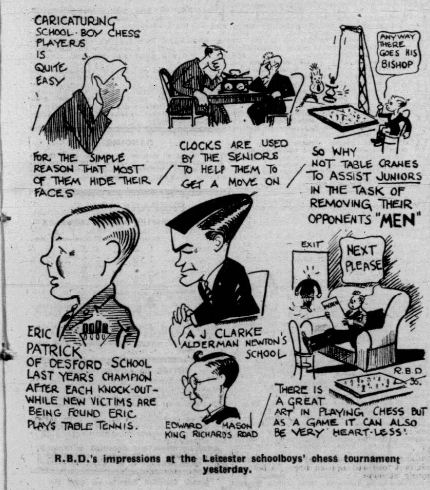

The local newspapers’ sports correspondents were invited along to have a look.

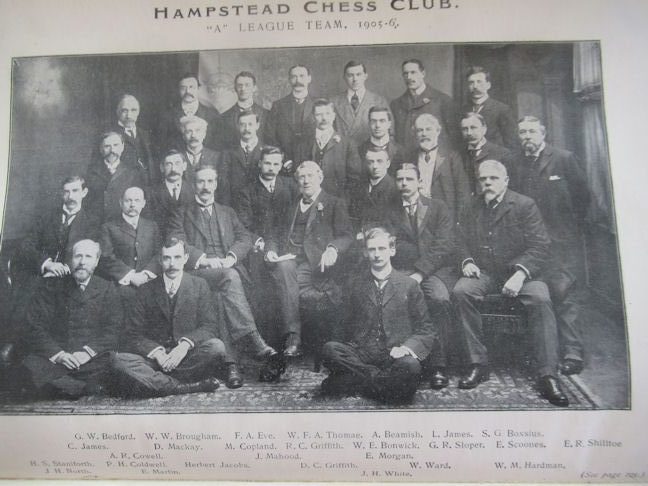

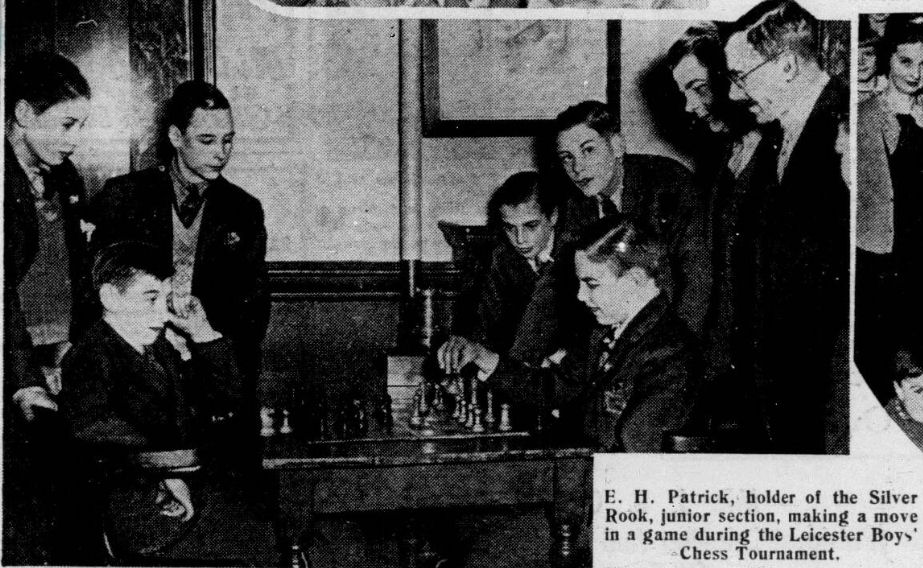

There was also a photographer present.

One paper even sent along their cartoonist: Eric Patrick was one of his subjects.

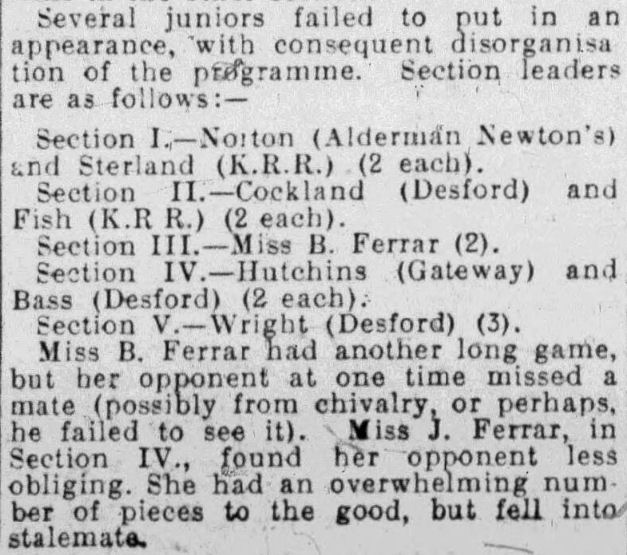

The results of the junior section were remarkable. All five of the preliminary sections were won by Desford boys, Eric Patrick retaining his title with a 100% score. Don’t forget that these were young offenders from difficult family backgrounds winning game after game against boys from top academic schools.

Needless to say, Eric again won the school chess prize as well. At the prizegiving, Cecil Lane blamed poor housing and large families on the boys’ problems.

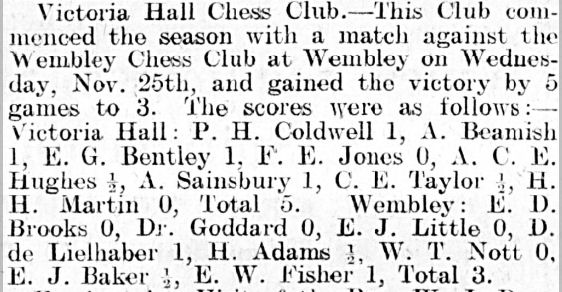

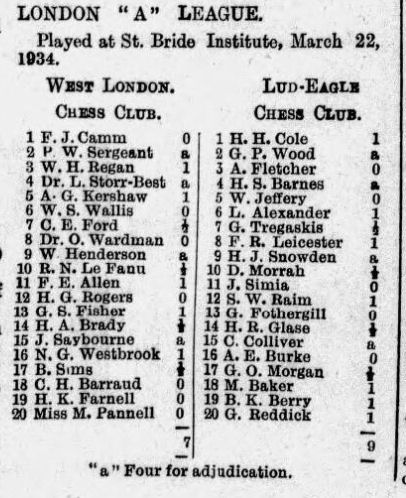

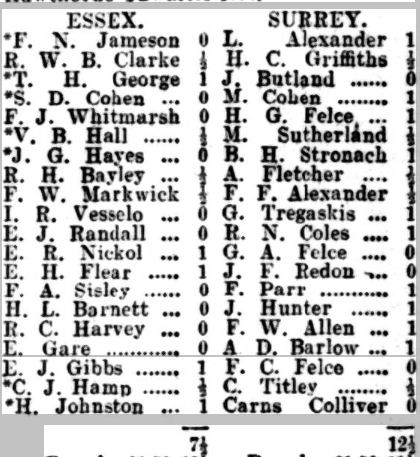

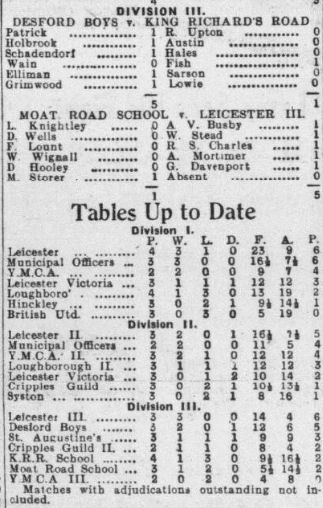

Later that year, the school entered a team into the third division of the Leicestershire Chess League, where they were playing against adult club teams as well as other school teams.

By December they were in second place, having won two and drawn one of their first three matches.

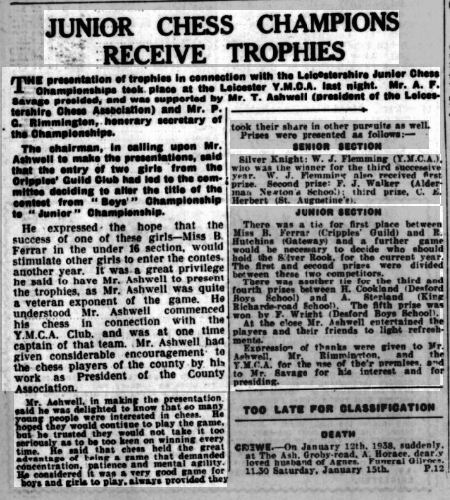

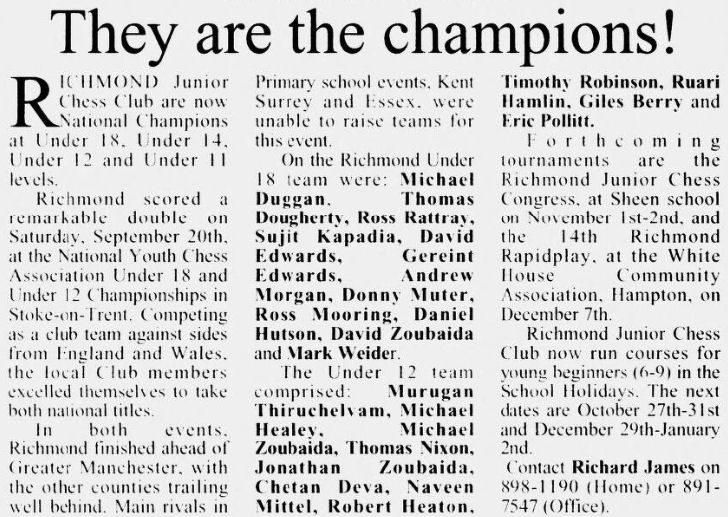

As the New Year approached, the county boys’ championships came round again. As in the previous year, seven Desford boys took part in the junior section, with Eric Patrick aiming for his third successive title. This time they didn’t have it all their own way, with only two of their players, including Eric, making the final four. He even lost a game in the final pool before regaining the Silver Rook.

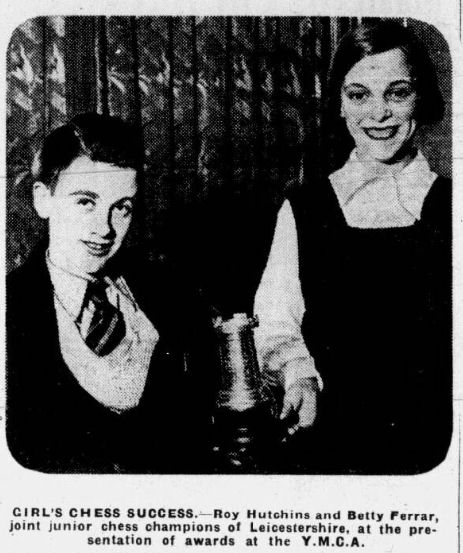

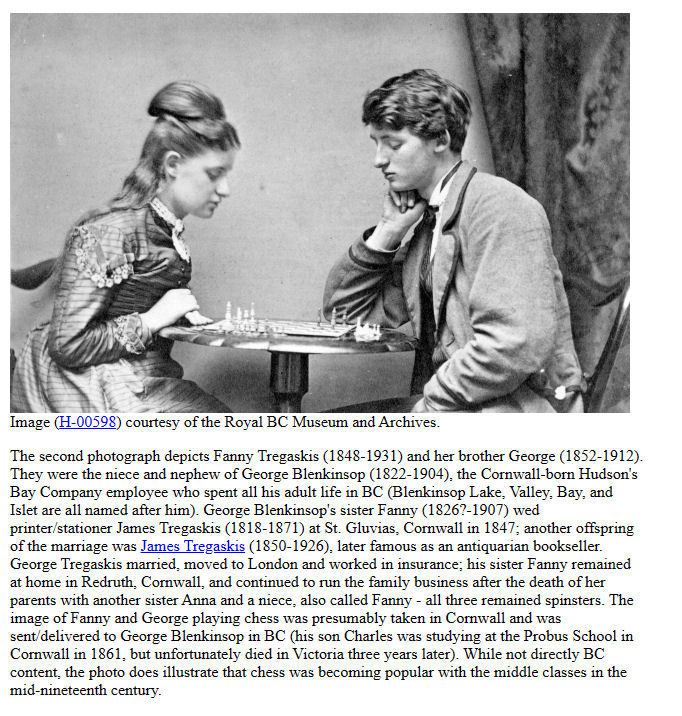

Again, we have a photograph.

Leicester Daily Mercury 31 December 1935

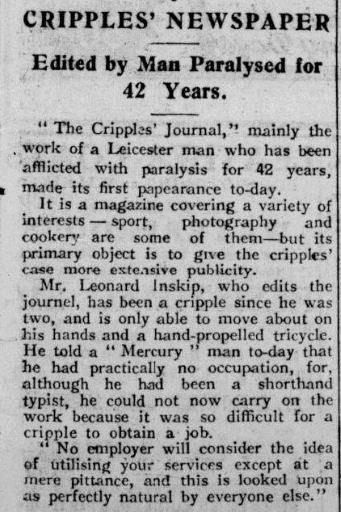

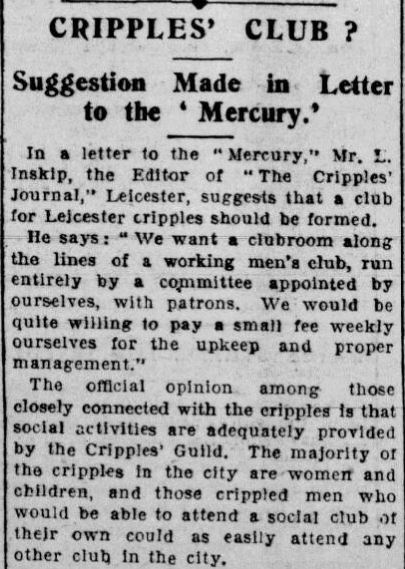

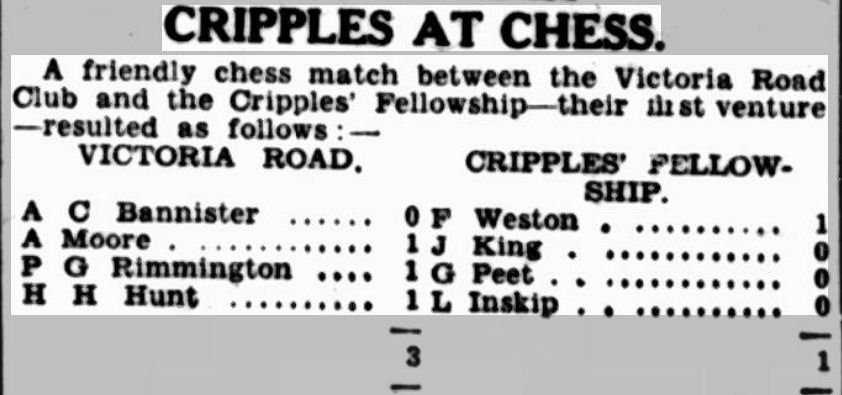

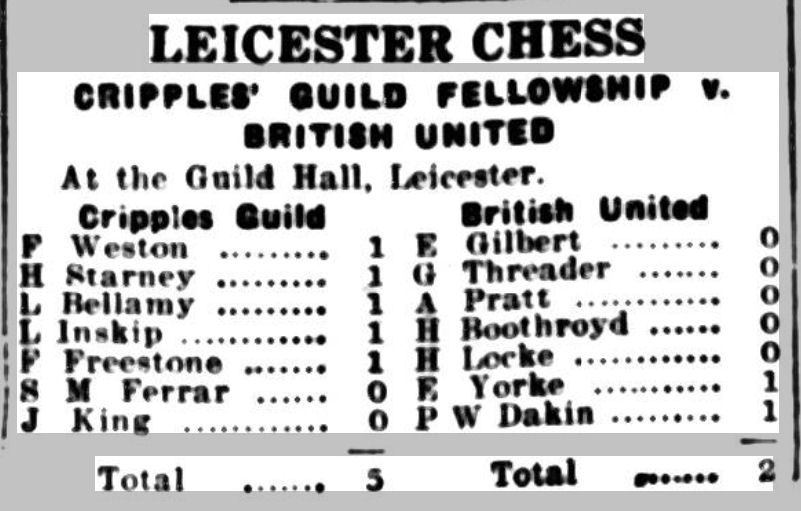

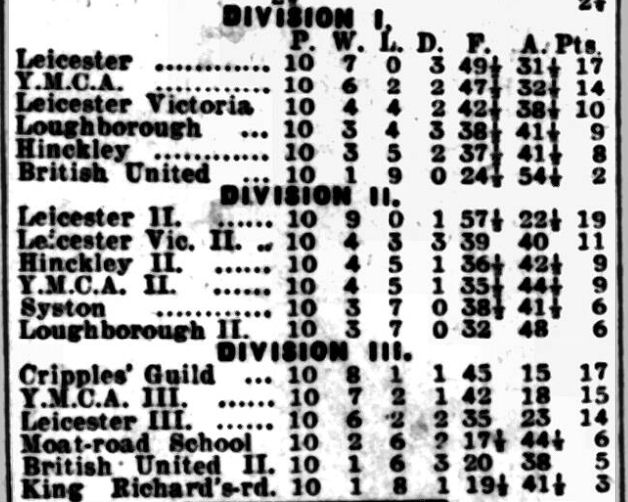

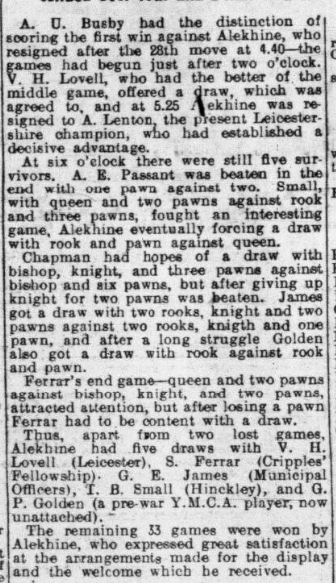

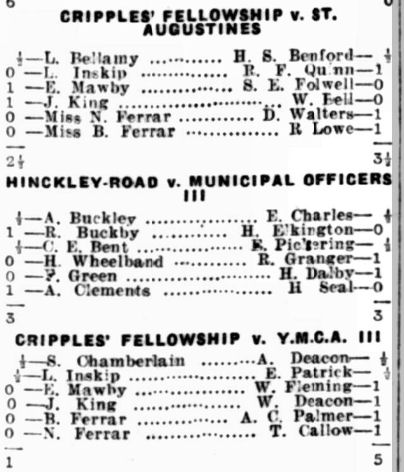

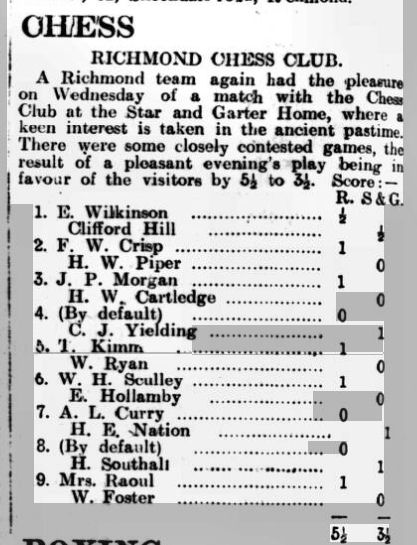

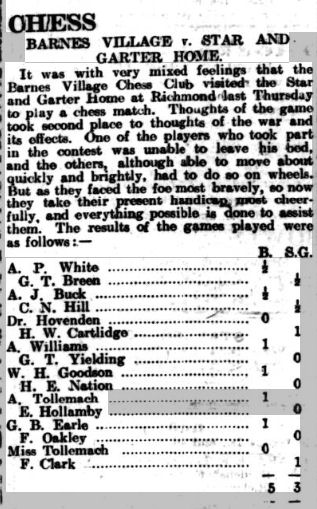

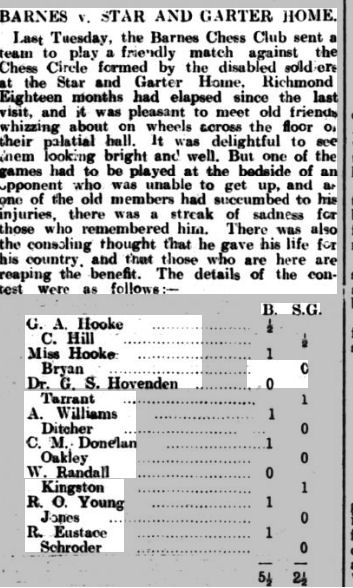

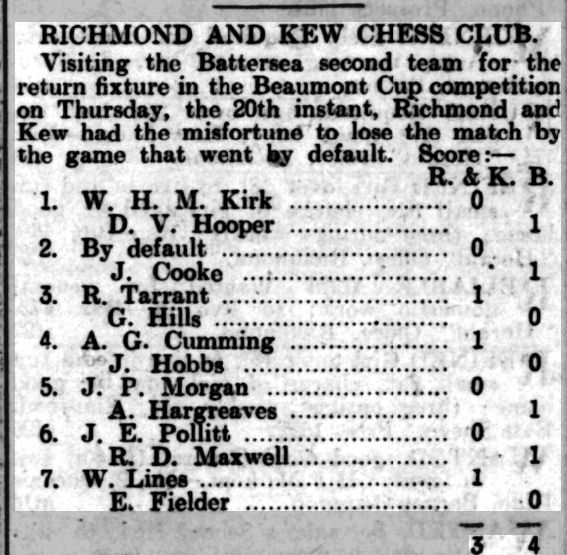

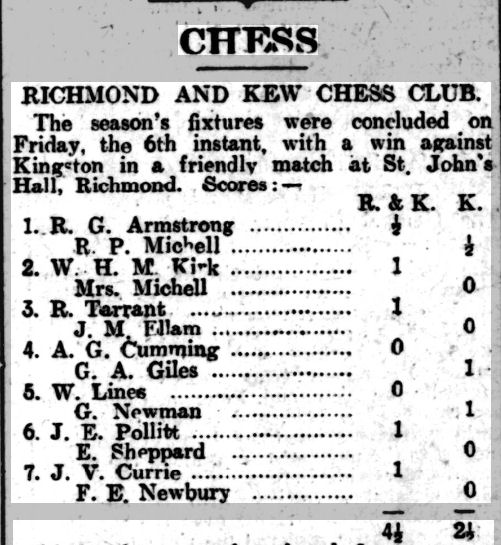

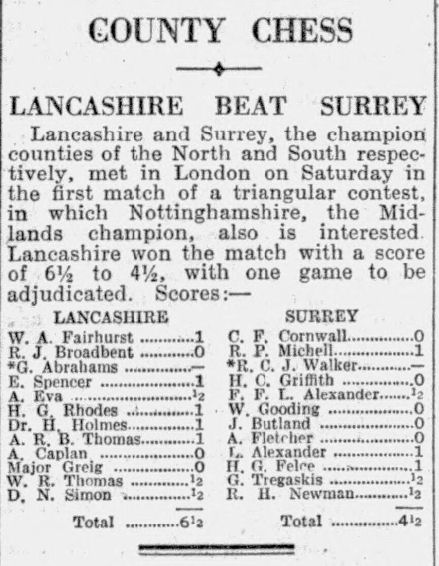

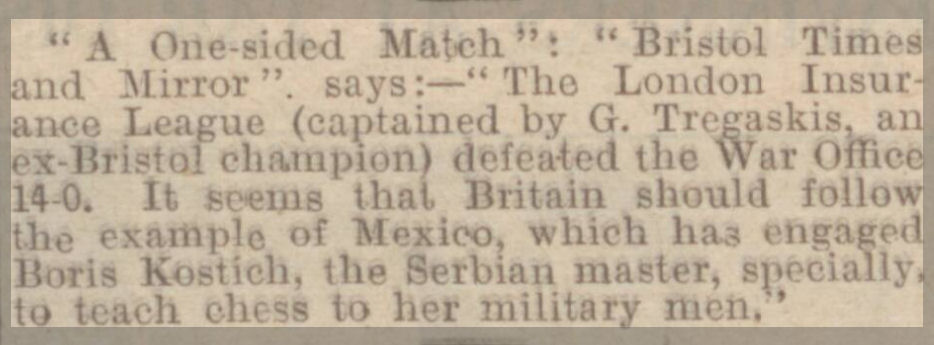

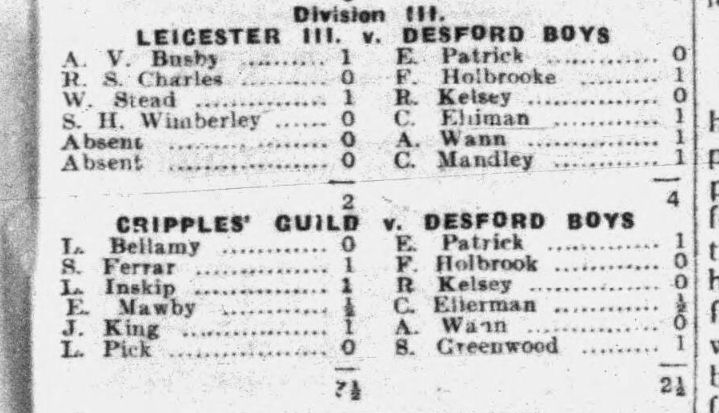

The school team continued to do well in the league. In these two matches they beat the early league leaders (Alfred Urban Busby was a more than useful player, beating Alekhine in a 1936 simul and, in 1989, a year before his death, losing a postal game to Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club’s Michael Franklin), with the aid of two defaults, but lost to the second team from the Cripples Guild.

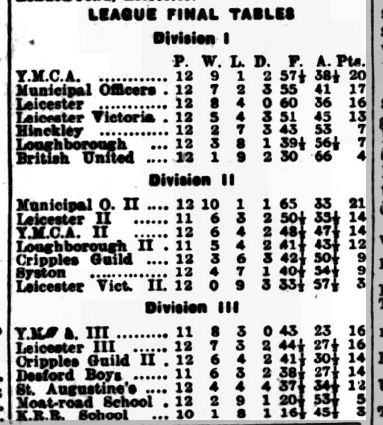

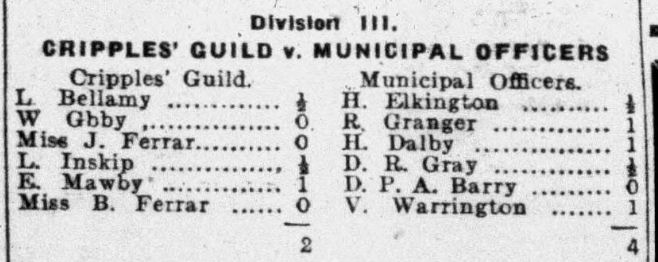

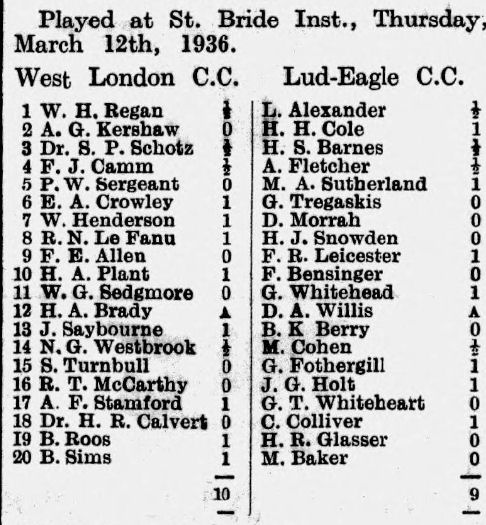

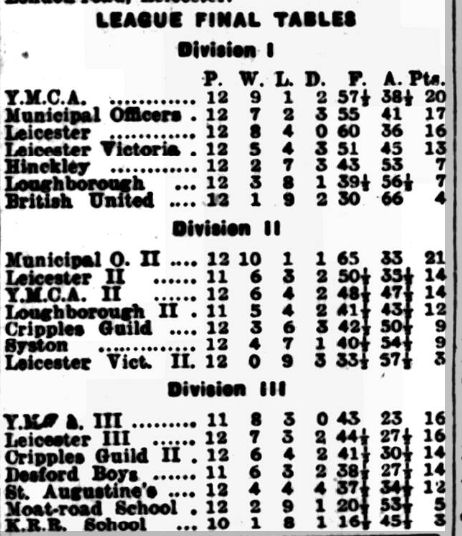

Here are the final league tables, with King Richard’s Road defaulting two matches. If their two opponents were awarded 6-0 victories, that would leave Desford Boys sharing second place.

Eric Patrick was now 15, and would have left Desford School that summer to make his way in the world. He continued playing chess, now representing YMCA in the league, and taking part in the senior section of the junior championships at the end of the year.

There was also a change in the Leicestershire League: they decided to run a separate schools division rather than allowing them to play against the adult clubs. For whatever reason, I don’t know, and, again for whatever reason, Desford didn’t enter the league for the 1936-37 season.

In the 1936-37 boys’ championships, Eric Patrick reached the final pool of the senior section but didn’t quite manage to win the title. The best Desford player in the junior section was Richard Kelsey, who finished in second place.

But the school would soon be hit by tragedy.

Cecil Lane’s wife Dora had died in April 1936. He needed some domestic help and his friend Sydney knew just the right person. Sydney had two sons, Basil and Humphrey. Basil was married to Alice Muriel Goodman: whose relation Nora would be ideal for the job.

Nora soon became rather more than a housekeeper, and, in September 1937, she and Cecil became man and wife.

As Mr RT Goodman had died more than a year before Nora was born, I suspect that the older lady in the photograph may have been her grandmother, not her mother, and that Nora was actually the illegitimate daughter of Alice’s sister Winifred. Was she aware?

And was Cecil aware that his brother Roderick died in hospital on the same day?

Anyway, the newly wed couple headed off to Scotland for their honeymoon. While there, Cecil was taken ill At first he seemed to be recovering, but then he took a turn for the worse, and, only 11 days after their marriage, Nora was left a widow.

Desford were still well represented in the younger section of the 1937-38 edition of the county junior championship (now no longer ‘Boys’ following the entry of Betty and Joan Ferrar, whom you met last time), with Hubert Cookland reaching the final pool and Norman Bass just missing out after a play-off.

There was more sad news on 4 November 1938, with the death of Sydney Ansell Gimson at the age of 78. The Leicester Mercury described him as a ‘Noted Leicester Rationalist and Public Man’.

You can also read an online biography here.

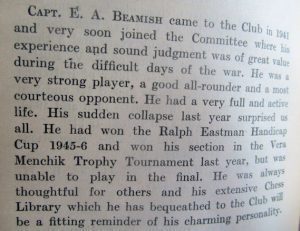

That, sadly, seems to have been the end of competitive chess at Desford Approved School. They appear not to have been represented in the 1938-39 county junior championships. Cecil and Sydney’s successors, I presume, didn’t share their interest in chess. Then, of course, war intervened. Some of the boys and young men who had been engaged in friendly combat over the chessboard, or, at least in the case of the Desford pupils, in the boxing ring, would soon be drawn into a very different fight: the fight against Fascism.

Join me again soon to find out what happened to Eric Harold Patrick and his chess playing friends after they left Desford.

But first, perhaps you’ll join me in drinking a toast to Cecil John Wagstaff Lane and Sydney Ansell Gimson, two men who, for their time, or even for our time, held enlightened and progressive views on education, and believed, as I do, that chess can have enormous social benefits for children of secondary school age.

I’d like to end on a personal note. Of all the people I’ve written about in these Minor Pieces, I think Sydney is the one I’d most like to have met. He seems to have been a man who shared my own opinions, interests and values in almost every respect. My political and religious views are, considering the 90 year gap in our ages, very similar to his. I also share his interests in the environment and in education, particularly in how schools should go about helping disadvantaged children, and in how chess can be used for that purpose. Sydney Ansell Gimson, you are one of my heroes.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Wikipedia

Who’s Who of Radical Leicester (Ned Newitt)

William Morris Society website

Leicester Secular Society website

Story of Leicester website

University of Leicester website