From the publisher:

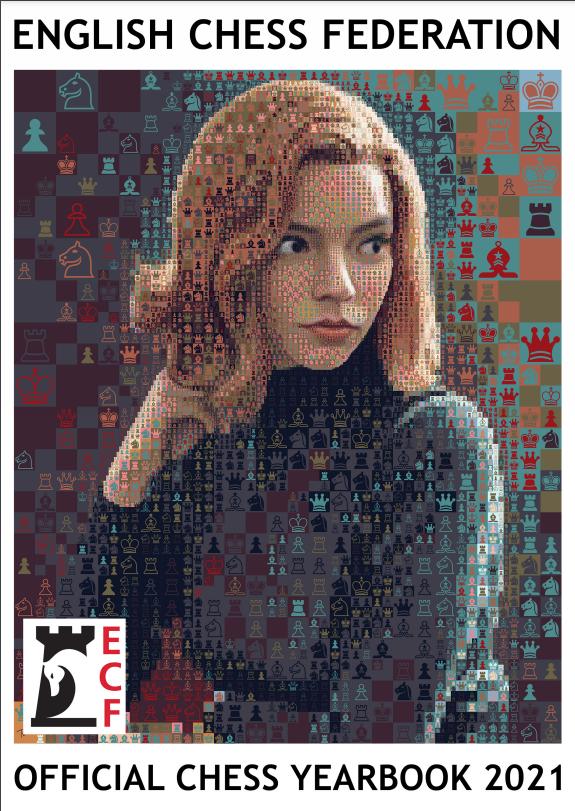

“Thanks to the efforts of a dedicated team of people within the English Chess Federation, the ECF Yearbook 2021 is now available in PDF form via this link – https://www.englishchess.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Yearbook-2021-complete-medres.pdf *

The printed version will follow in a little while; it will be free to Platinum members of the ECF and may be purchased (while stocks last) for £15.50 by ECF members in all other categories [online form to follow].

Special thanks go to IM Richard Palliser at CHESS Magazine, Dr John Upham at British Chess News, Director of Home Chess Nigel Towers, compiler Andrew Walker and to our determined team of proof readers – Dagne Ciuksyte, Roger Emerson, Stephen Greep, James Muir, Mike Truran and John Upham.”

End of blurb.

One thing I failed to predict for 2021 (amongst numerous others) was having a hardcopy of the ECF Yearbook to review. I was not sure there would be a yearbook of any kind based on a lack of material to report combined with an impending fear of the hardcopy version being deprecated.

At this juncture I feel it appropriate for the Yearbook to (correctly) quote (but often misquoted) Samuel Langhorne Clemens (aka Mark Twain if you didn’t know otherwise) that

The report of my death was an exaggeration

A Yearbook of English chess was “first published sometime between 1904 and 1913” but not by the BCF. The first BCF Yearbook may well have appeared in the 1930s but the jury remains unclear. BCF Yearbooks continued up until 2005 and then became the ECF Yearbook in 2006 which suggests at least 90 odd editions. The events (or rather the lack of events!) after March 2020 led myself to believe we would not see an ECF Yearbook until 2022 if at all!

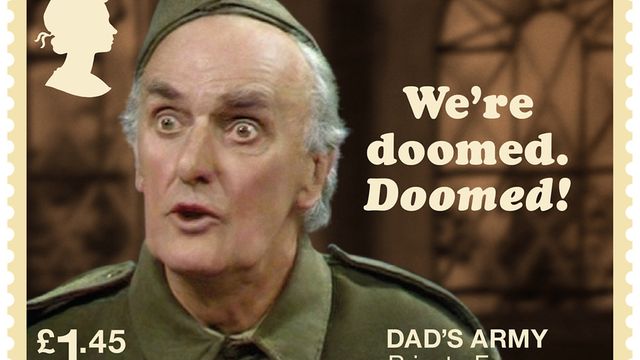

Despite all this Private Frazer style doom and gloom

and thanks to the good offices of Andrew Walker (ECF Webmaster) we not only have a Yearbook but, dare I say it, we have an excellent one with more pages than the previous year! So, (as they frequently say on television) how did they do that?

The Contents are divided into 15 sections viz:

- Report of the Board to Council

- Strategy and Business Plan

- New Initiatives – GoMembership / Queen’s Gambit Scheme

- Chess in Prisons

- John Robinson Youth Chess Trust

- The Chess Trust

- The ECF Academy

- ECF and Other Awards

- Home News 2020 – from CHESS Magazine

- Events around England

- Nigel Tower’s Online Chess Report

- Off the Wall

- Mark Rivlin (and Tim Wall) – the interviews

- Remembering -from British Chess News

- Endgame Studies / Chess Problem News

Being a Yearbook the overall layout would normally include formal content that you might be forgiven for leaving for the ubiquitous “rainy day”. Perhaps we should update that and leave things for a “sunny day”?

ECF CEO, Mike Truran OBE kicks-off with the year’s positives and he immediately thanks those who carried largely unpaid work on behalf of English chess and the ECF.

Gone are the lengthy (dare I say tedious?) lists of officials, Title holders, Past Champions and all the other content which is largely unchanged year-on-year. Most of this information has been migrated on-line and may be found on the ECF’s satellite Resource web site. This makes complete sense since this location may be maintained throughout the year rather than being cast in stone (or rather paper).

This is followed by an itemised list of the ECFs Strategy and Business plan which contains many laudable and worthy statements of intent some of which, at least, will hopefully eventually be brought to fruition.

I won’t go through every section but I would like to pick out a few highlights. It was gratifying to read of a small army of volunteers whose efforts were recognised with various awards including Bude Chess Club and the Hull International Congress.

Winner of ECF Book of the Year was no surprise whatsoever and justly deserved. It was a pleasure to read of those who had become FIDE Arbiters : we badly need such persons if we are to run sufficient FIDE rated events to cater for the increasing demand especially since England has recently abandoned the Clarke Grading system and replaced it with an Elo style rating system. I could always mention the Netflix phenomenon of Walter Tevis’s Queen’s Gambit but I won’t. I mentioned it once(?) and I think I got away with it.

So, we have covered 8 out of 15 sections as we turn to page 27. Its going to be a thin one for 2021 surely? Not so. Thanks to CHESS Magazine we have reports covering 43 pages of home news reported by the much loved magazine launched in 1935 for 1/- (a shilling which is 5 new pence for those born post February 15th 1971) by BH Wood. Within these pages we have 16 annotated games from the pages of the aforesaid publication. BHW would have been most proud that his magazine was doing its bit for 2020 as it did during the Second World War.

Events Around England runs to 32 pages of more familiar content such as reports of the Four Nations Chess League (4NCL), the ECF Counties Championship, Hastings International Congress and so on and so forth with that well-known “English” event, Gibraltar making a welcome appearance thanks to the reporting of John Saunders.

Now at page 101 (and less than half-way through) you might think what else can there be to report?

Indeed and at this point the ECF’s new Director of Home Chess, Nigel Towers, steps up to the plate and offers 15 pages reporting of the largest growth sector for the English chess scene, (no not discussions of ratings versus gradings) but, chess played on-line (as some might call it The InterWeb) including the scores of eight games.

Tim Wall continues our journey adding a lighter and more humorous touch with a veritable potpourri of musings on various topics including absent minded cats, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (aka Lenin), Arthur Ransome and a modern resurrection (with the joie de vivre) of Howard Staunton via HSs enjoyable Twitter feed. Who is the person behind the account? Answers on a postcard to….

Not to be outdone, the ECF’s Newsletter compiler and editor, Mark Rivlin conspired with the aforementioned young Timothy to bring us a gathering of lockdown interviews with the great and good including Danny Gormally, Shreyas Royal, Lorin D’Costa, James and Jake. If you want to know who James and Jake are (and I do now!) then purchase the Yearbook!

The largest (58 pages) section for 2020 could leave me facing charges of nepotism… British Chess News was delighted to be invited to provide content and twelve biographies of some of the most significant contributors to English chess. These names include Harry Golombek OBE, Hugh Alexander CBE, Vera Menchik, Tony Miles and Fred Yates. I won’t comment on the articles veracity but leave that for you to discover.

The final section, and one of my favourites, is that of the Studies Editor of British Chess Magazine, Kent based Ian Watson. Ian provides the best new studies of 2020 and reflects on the life of one of England’s foremost composers, Dr. Richard K Guy.

As a taster, here is Ian’s contribution.

At 209 pages we have reached the end. The English Chess Federation have done a splendid job in getting this Yearbook produced and published in challenging circumstances. Long may the tradition continue!

John Upham, Cove, Hampshire, 20th April, 2021

Book Details :

- Hardcover : 209 pages

- Publisher: English Chess Federation; 1st edition (1st April 2021)

- Language: English

- Product Dimensions: 30 x 21 x 1.5 cm

- Cost of Hardcopy: £15.50 (ECF members), £17.50 (non-members)

- pdf download : https://www.englishchess.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Yearbook-2021-complete.pdf

Official web site of English Chess Federation