World Champion Chess for Juniors : Learn From the Greatest Players Ever : Joel Benjamin

From the book’s rear cover :

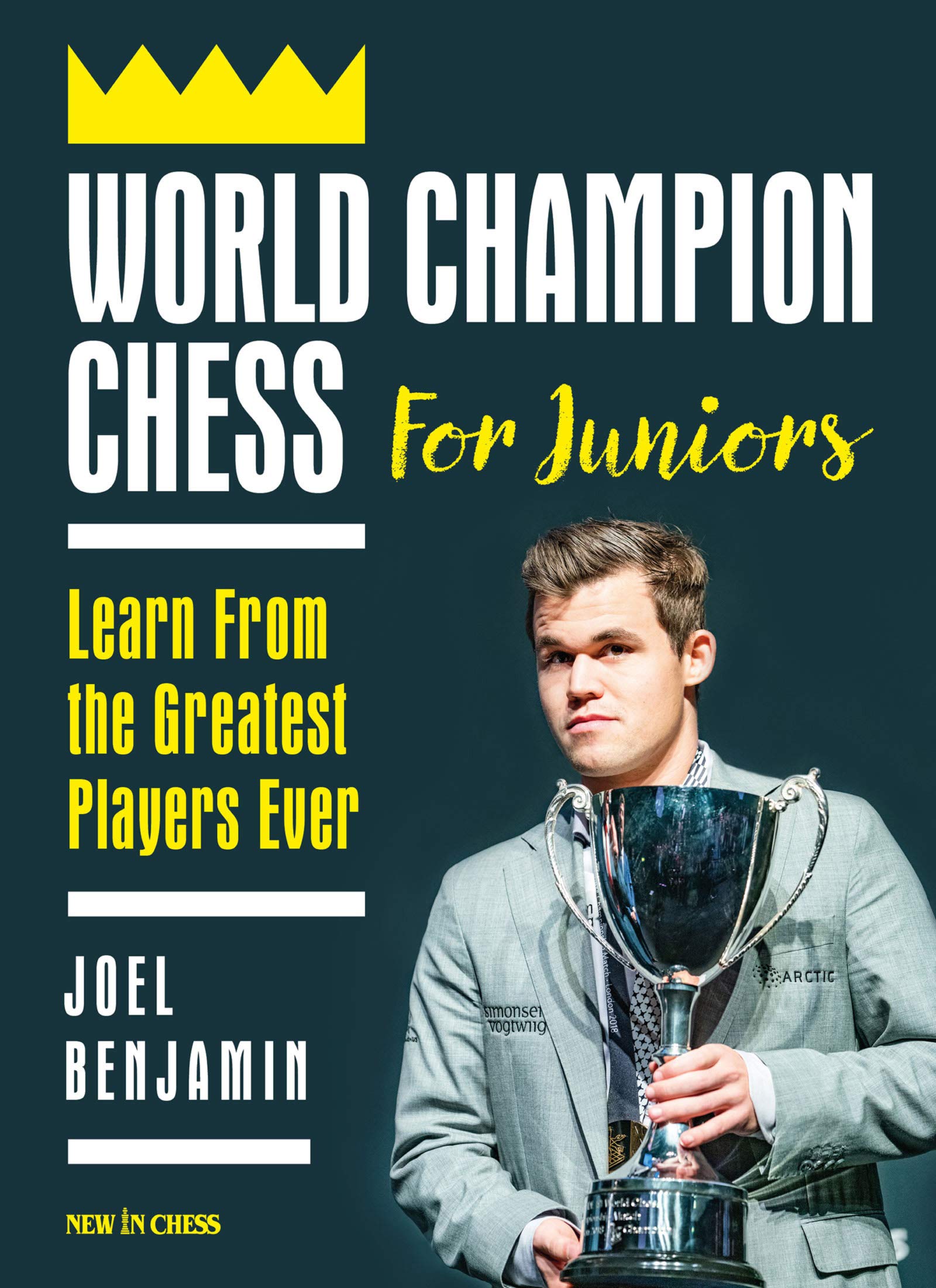

“Grandmaster Joel Benjamin introduces all seventeen World Chess Champions and shows what is important about their style of play and what you can learn from them. He describes both their historical significance and how they inspired his own development as a player. Benjamin presents the most instructive games of each champion. Magic names such as Kasparov, Capablanca, Alekhine, Botvinnik, Tal, and Karpov, they’re all there, up to current World Champion Magnus Carlsen. How do they open the game? How do they develop their pieces? How do they conduct an attack or defend when necessary? Benjamin explains, in words rather than in chess symbols, what is important for your own improvement. Of course the crystal-clear style of Bobby Fischer, the 11th World Champion, guarantees some very memorable lessons. Additionally, Benjamin has included Paul Morphy. The 19th century chess wizard from New Orleans never held an official title, but was clearly the best of the world during his short but dazzling career. Studying World Champion Chess for Juniors will prove an extremely rewarding experience for ambitious youngsters. Trainers and coaches will find it worthwhile to include the book in their curriculum. The author provides many suggestions for further study.”

“Joel Benjamin won the US Championship three times and has been a trainer for almost three decades. His book Liquidation on the Chess Board won the Best Book Award of the Chess Journalists of America (CJA), and his most recent book Better Thinking, Better Chess is a world-wide bestseller.”

Naturally enough, given that I’ve been teaching chess to children since 1972, I’m always interested in reading chess books with ‘juniors’ or ‘kids’ in the title.

Let’s see what we have here.

From the introduction:

If you are not a junior, please don’t toss this book aside; there is still a lot of cool analysis and history in here for you. But I have written this book, primarily, to reach out to younger players. At any point in history, we see a ‘generation gap’, where young people see the world in a very different way than their elders. If you are, let’s say, a teen or a tween, you probably process most chess material from a computer. You follow recent events, work on tactics puzzles, practice against an engine, or whatever works for you. This may match your lifestyle of playing Minecraft or (worse) Fortnite on your I-pad instead of reading books.

A few years ago, I was horrified to learn that two of my (young) fellow instructors at a chess camp could not name the World Champions in order (or even place them roughly in their time periods). For someone of my generation, that fundamental lack of knowledge was unthinkable. And while I accept that kids today learn things in different ways, I feel that they are still missing out on their ignorance of knowledge provided by books.

I’m in complete agreement with Joel Benjamin here. I believe that, for all sorts of reasons, learning about the great champions of the past should be part of everyone’s chess education. This issue has been raised in the introduction of several books I’ve reviewed recently: some authors agree, but others, sadly, don’t.

And from the back cover (presumably written by the publishers):

So you want to improve your chess? The best place to start is looking at how the great champs did it!

I’m not in agreement with this, though. I’ve spent the past 45 years or so failing to understand why round about 90% of chess teachers consider it a good idea to demonstrate master games, usually with sacrificial attacks, to inexperienced players.

What does it mean to write a book for ‘juniors’, anyway? What do we mean by a junior? Perhaps we mean Alireza Firouzja (rated 2759 at age 17 as I write this)? Or do we mean Little Johnny who’s just mastered the knight move? There’s an enormous difference between writing for 7-year-olds, writing for 12-year-olds and writing for 17-year-olds. Benjamin mentions ‘teens and tweens’ in his introduction. How do you write for this age group? Do you try to appear ‘down with the kids’ by writing things like ‘Yay, bro! Morphy was a real sick dude!”? Maybe not, but you might, as he does, throw in a lot of ‘cools’ and a few ‘legits’, as well as a lot of exclamation marks at the end of sentences.

There’s also an enormous difference between writing for players rated, say 500, 1000, 1500 and 2000. The nature of this difference is something I’ve been thinking about for many years. I think the most helpful information I’ve found about teaching at different levels is from this article (apologies if you’ve seen it before), in particular the section entitled ‘experts learn differently’. I’d consider a novice (apprentice) to be someone with a rating of under 1000, an expert (guild member) to have a rating of 2000 plus, and everyone else (which includes the vast majority of adults who know the moves) to be journeymen/women.

Novices, then, learn best through explicit instruction and worked examples, while experts learn best through discovery and/or an investigative approach. If you’re writing for a readership between novices and experts, you’ll use a mixture of both methods. I’d also suggest that, given the relative inexperience and immaturity of younger children, you’d probably be well advised to add two or three hundred points onto your novice/expert split.

Top GM games these days are, of course, insanely complicated, and only an expert player could expect to learn anything from looking at, say, a Carlsen – Caruana game.

Let’s plunge into this book, then, and decide who would benefit most from reading it, in terms of both age and rating.

Before I go any further, I’d add that there are many reasons you might want to read a chess book: information, enjoyment, inspiration or instruction, for example, but this book, as you might expect from the 21st century Zeitgeist, nails its colours firmly to the flagpole labelled ‘instruction’. LEARN from the Greatest Players Ever.

Taking the reader on a journey through chess history, stopping off on the way to introduce us to each of the world champions in turn, it reminds me of two other books I’ve reviewed on these pages: this and this (also from New in Chess), neither of which impressed me, as a cynic with a pretty good knowledge of chess history, greatly.

We start off, not unreasonably, with Morphy (the greatest showman). In every chapter we get some brief biographical notes, a handful of annotated games and a couple of unannotated games. Here he is, crushing the Aristocratic Allies at the opera house, and sacrificing his queen against Louis Paulsen in New York. Yes, you’ve probably seen them hundreds of times before, but the target reader, a young player with little knowledge of chess history, might not have done. The notes at this point focus, understandably, on ideas rather than variations.

Next up is Steinitz (the scientist). We visit Hastings, of course, just in time to witness von Bardeleben disappearing from the tournament hall rather than resigning. We also see him daringly marching his king up the board in the opening and exploiting the advantage of the two bishops. He beats Chigorin in a game that starts 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. d3 when Benjamin points out that “With the rise of the Berlin endgame this move has become very popular in the 21st century”. Which is very true, but assumes that the reader knows something about the Berlin endgame. (It’s mentioned in slightly more detail later in the book, but you should describe it the first time you mention it.) Later on, though we’re advised not to forget the en passant rule. So this appears to be a book for readers who understand all about the Berlin endgame but might not remember en passant.

We move into the 20th century: Lasker (the pragmatist) beating Capa in an Exchange Lopez ending, Capablanca (the endgame authority) himself winning a rook ending against Tartakower, Alekhine (the disciplined attacker) winning complex encounters against Bogoljubov and Réti, Euwe (the professional amateur) in turn winning the Pearl of Zandvoort against Alekhine.

As we approach the present day, the games get more complicated and not so easy to use for specific lessons. The great Soviet champions all had their distinctive styles, though. There’s Botvinnik (the master of training), Smyslov (the endgame artist), Tal (the magician), Petrosian (the master strategist) and Spassky (the natural).

Then, of course, Fischer (the master of clarity), Karpov (the master technician) and Kasparov (the master of complications) are introduced as we approach the 21st century.

Today, all the top grandmasters excel in all areas of the game, and, with the aid of computer preparation, their games are often mind-boggling in their complexity. Kramnik is awarded the epithet ‘the strategic tactician’, but this could apply to any 21st century great.

It’s time to look at a few examples of Benjamin’s annotations, so that you can decide whether it’s a suitable book for you, your children or your students.

Here, at Linares in 1997, Topalov, the master of the initiative, has sacrificed the exchange for … the initiative.

White, Gelfand, is considering his 23rd move.

An exchange to the good, White has some leeway in defense. He must appreciate the need to give back to the community here.

Topalov points out that 23. Qd2 Ne5 24. Rxe5 Qxe5 25. Nxb7? is too dangerous (after almost any rook move, actually) but White can hold the balance with 25. b4 a5 26. Qe2!. White can play more ambitiously with 23. b4 Ne5 24. Rxe5 Qxe5 25. Nb2, though Topalov would likely pitch a pawn for good play after 25… d3 26. Nxd3 Qd4+. Finally, even the radical (and inhuman, I think) 23. Nc3!? dxc3 24. Qxc3 looks playable, as suddenly some black minor pieces look misplaced and the white rooks are working well. Chess players need a good sense of danger, but here Gelfand’s Spidey-sense fails to tingle.

An excellent note, I think, but it would, inevitably given the complexity of the position, be instructive for older and more experienced players.

For the record, the game continued 23. Ne4? Ne5 24. Qg5 Re8! 25. Rd2? when Topalov missed 25… Ng4+! 26. Kg1 Qxg5 27. Nxg5 Re1#. but his choice of Qc4 was still good enough to win quickly.

For another example of the style of annotation in this book, in this position Anand, the lightning attacker, has unleashed a TN against Kasparov’s Sicilian in the 1995 World Championship match. What will the champ play on his 20th move?

20… Bxb5

Anand had expected 20… Qa5, which has been played in subsequent practice. However, Kasparov would have had a lot to calculate and evaluate there. When you hit your opponent with an unpleasant opening surprise, they may hesitate to risk the most challenging lines.

20… Qa5!? 21. Nxd6 Bxa4 22. Bb6 Rxd6 and now Anand considered two lines:

A) 23. Qxd6 Rxd6 24. Bxa5 Bxf4 (24… Bxc2? 25. e5+-) 25. Rxb7 Bxc2 26 Rd8 Rxd8 27. Bxd8 Bxe4! 28. Rb4 Bxf3 29. Rxf4 Bd5 30. Bxf6 gxf6 31. Rxf6 and the position should be drawn;

B) Anand preferred 23. Bxa5! Rxd3 24. cxd3 Bxd1 25. Bxd1. White doesn’t win any material but keeps the potential for long-term pressure.

Well, I hope you followed all that.

The main part of the book concludes with Carlsen, the master of everything and nothing.

Here’s a position from a game which, according to Benjamin, displays his accuracy and brilliance in attacking play.

He’s playing the white pieces against Li Chao (Doha 2015) and is about to make his 24th move.

24. d5!!

Carlsen breaks down the defense with a beautiful interference tactic. By attacking the knight on b6, he enables the deadly push e5-e6.

White could easily go wrong here:

A) 24. gxf5 Nc4 25. Nxg6+ (25. e6?? a3 wins for Black) 25… Ke8 26. e6? a3! 27. exf7+ Kd7 28. f8N+! Ke8 29. bxa3 Rxa3+ 30. Kb1 Rda8 31. Na4! and White barely forces Black to take a perpetual. Instead 25. Ncd5!! wins for White. The idea is to kill the mate with Rc1xc4 and then proceed on the kingside;

B) Again the take-first mentality 24. Nxg8+? Ke8 loses ground. White can probably still win with 25 d5! but it’s a lot less clear.

Again, good analysis, although Benjamin’s notes do include rather a lot of ‘perhaps’ and ‘probably’, which you may or may not care for.

That’s not quite the end of the book. There’s some ‘fun stuff’ at the end, most usefully a 36 question tactics quiz: some easy and familiar but others more challenging.

This is a good book of its kind, although if you like the first half you might find the last few chapters too hard, and if, like me, you enjoyed Benjamin’s coverage of contemporary players, the first half will offer you nothing new.

But is it a book for juniors, though?

Little Johnny, aged 8, is doing well in his school chess club, playing at about 1000 strength. His parents, who know little about chess, would like to buy him a book so that he can learn more and perhaps play like Fischer, Kasparov or Carlsen. What could be better, they think, than learning from the world champions? Is this a suitable book for him? Definitely not: it’s much too hard in every respect. Instead, as a young novice, he requires a book with explicit instruction and worked examples.

Jenny is 12, has a rating of about 1500, and is starting to play in adult competitions. Perhaps this would be a good book for her. Well, it’s more suitable for her than for Johnny, but again it’s rather too hard: I think you’ll agree from the extracts you’ve seen that it’s really aimed at older and more experienced players. She’ll still need, for the most part, explicit instruction and worked examples, but pitched at a higher level than Johnny’s book.

Jimmy is an ambitious 16-year-old with a rating of 2000 who would like to reach master strength while finding out more about the history of the game he loves. This could be an ideal book for him: as a player approaching expert standard with perhaps a decade’s experience of chess, he’d benefit from discovery and/or an investigative approach, for which he can use annotated grandmaster games. But would he be seen dead carrying a book with ‘juniors’ in the title under his arm? And, at least here in the UK, there are very few ambitious 16-year-olds around to read this book.

It’s nothing personal to do with the author or the publishers, but my view is that many people buy books which are much too hard to be useful, either for themselves or for their children or students. On the other hand, books which really would be helpful don’t sell. And you can’t blame publishers for bringing out books they think people will buy.

You could write a great book for Little Johnny, I think. A colourful hardback with short chapters about each champion. Photographs and perhaps also cartoons of each. A few simple one-move puzzles in each chapter taken from their games: perfect novice-level tuition. Some historical background as well. Maps to show the champions’ countries of birth, and, perhaps, where else they lived. The word for chess and the names of the pieces in their native languages. Cross-curricular benefits: children will learn about history, geography and languages as well as chess. Age-appropriate in terms of chess, vocabulary and grammar as well. All primary schools would welcome a few copies for their school library.

You could also write a good book for Jenny. You could introduce each champion again, and then look how the different champions interpreted openings like the Ruy Lopez and the Queen’s Gambit, how they played kingside attacks or IQP positions, how they navigated rook endings. Perhaps also, where available, some simple games played when they were Jenny’s age. She’ll learn, at a fairly basic level, about the history of chess ideas as well as the champions. You’d probably also want to include some puzzles where you have to look two or three moves ahead. This is how you teach students who are neither novices (like Little Johnny) or budding experts (like Jimmy). A mixture of harder ‘novice’ material and easier ‘expert’ material.

I think both Johnny’s and Jenny’s books should include female as well as male champions: Jenny, as well as Johnny, would like role models she can relate to. You might think it remiss of Benjamin (or New in Chess) not to have included any Women’s World Champions in this book.

It’s a good book, then, although, by it’s nature it’s not going to be earth-shatteringly original. But it’s not a book for juniors. If it was called simply World Championship Chess, or Learn Chess from the Champions I wouldn’t really have a problem with it.

I really ought to add that the games are well chosen and expertly annotated (if you don’t mind the slightly casual style), and the author, unlike others ploughing the same field, doesn’t stray beyond the limits of his historical knowledge.

It’s also, as to be expected from this publisher, excellently produced, with, unusually for these days, a refreshing lack of typos.

I mentioned earlier the reasons why you might want to read a chess book. You may well find this book informative, especially if your knowledge of chess history is lacking. It’s certainly an entertaining read: the author’s lively style of writing and annotation shines through. You’ll probably also find it inspirational to be able to play through the greatest games of the greatest players of all time. But is it also instructional? I’m not really convinced that this is the most efficient method of teaching anyone below 2000. It’s certainly not an efficient method of teaching this very experienced, 1900-2000 strength, player.

Recommended, then, if you want to know more about the world champions, but not really a book for juniors.

Richard James, Twickenham 12th April 2021

Book Details :

- Paperback : 256 pages

- Publisher: New in Chess (7th August, 2020)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9056919199

- ISBN-13:978-9056919191

- Product Dimensions: 16.51 x 1.78 x 22.86 cm

Official web site of New in Chess