According to Wikipedia :

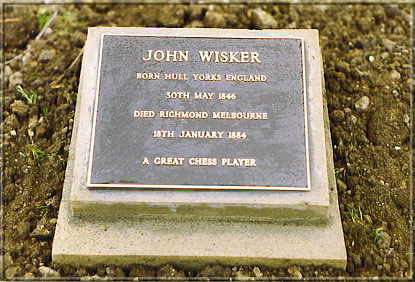

Zenón Franco Ocampos (American Spanish: [seˈnoɱ ˈfɾaŋko oˈkampos];[a] born 12 May 1956, Paraguay) is a chess grandmaster (GM) from Paraguay. In the 1982 Chess Olympiad at Lucerne, he won the gold medal at board one by scoring 11 of 13. In the 1990 Chess Olympiad at Novi Sad, he shared first place at board one with 9 points in 12 games. As of 2007, Ocampos is the top-ranked player and only GM in Paraguay (now, there are three GMs: Zenon Franco, Axel Bachmann and Jose Cubas). He has written several books on chess for Gambit Publications under the name Zenon Franco.

A few days ago my friend Paul Barasi asked me a question on Twitter: “Does planning play a distinctive & important role in deciding inter-club chess match games? I don’t hear players saying: I lost because I picked the wrong plan or failed to change plan, or won by having the better plan. Actually, they never even mention the subject.”

I replied: “It does for me. I usually lose because my opponent finds a better plan than me after the opening. But you’re right: nobody (except me) ever mentions this.”

I can usually succeed in putting my pieces on reasonable squares at the start of the game, but somewhere round about move 15 I have to decide what to do next. If I’m playing someone 150 or so Elo points above me (as I usually am at the moment), I’ll choose the wrong plan and find out, some 20 moves later I’m stuck with a pawn weakness I can’t defend and eventually lose the ending.

Perhaps Zenón Franco’s book Planning Move by Move will be the book to, as the blurb on the back suggests, take my game to the next level.

There are five chapters: Typical Structures, Space Advantage, The Manoeuvring Game, Simplification and Attack and Defence, with a total of 74 games or extracts. Although most of the games are from recent elite grandmaster practice, there are also some older games, dating back as far as Lasker-Capablanca from 1921. Three masters of strategy, Karpov, Carlsen and Caruana, make regular appearances.

Each game is interspersed with exercises (where the author is asking you to answer his question) and questions (which you might ask the author).

Compared to the Kislik book I reviewed last week which covers fairly similar territory, Franco’s book is more user friendly for this reason. It’s the difference, if you like, between a teacher and a lecturer. Kislik is talking to you from the demo board without giving you a chance to interact, while Franco is answering your questions and asking you questions in turn.

Let’s take as an example from the book Game 31, which is Caruana-Ponomariov Dortmund 2014

In this position, with Caruana, white, to play, you’re given an exercise.

“A decision must be taken. What would you play?”

White played 20. Rde1!

Answer: “Seeking the favourable exchange of dark-squared bishops and preventing 20… f6 for tactical reasons. Caruana didn’t see a favourable way of continuing after 20. h4 f6 and he commented that he wasn’t happy about allowing … h4, but he thought it was more important to prevent … f6.”

You might then ask the question: “But how did 20. Rde1 prevent 20… f6?”

Answer: “I’ll answer that with an ….”

Exercise: “How can 20… f6 be punished?”

Answer: “White can gain a positional advantage by exchanging the bishops with 21. Be5, but even better is 21. exf6 Bxf6 and now 22. Bxc7! Kxc7 23. Qf4+ wins a pawn.”

Taking you through to the end of the game, we reach this position with Caruana to play his 39th move.

“Exercise: Test position: ‘White to play and win’.”

You might want to solve this exercise yourself before reading on.

With any luck you’ll have spotted the lovely deflection 39. Re7!!

“Exercise: “What’s the key move now for solving the problem I set you?”

If you found the previous move you’ll have no problem finding the second deflection 40. Ba6 Kxa6 41. Qa8#

You’ll see from this example that the book is far from just a guide to chess strategy. At this level tactics and strategy are inseparable, and in order to solve Franco’s exercises you’ll have to calculate sharply and accurately both to justify your chosen plan and to finish your opponent off at the end of the game.

What we have, then, is a collection of top class games and extracts with annotations which are among the best I’ve seen. Copious use is made of other sources: the notes on the above game incorporate, with acknowledgement, Caruana’s own notes which can be found, amongst other places, on MegaBase. Franco also refers to computer analysis, in places making interesting comparisons between modern (early 2019) and older engines, and frequently comments on the difference between human and computer moves.

Having said that, the games are not easy, and, although all readers will enjoy a collection of great games instructively analysed, I would suggest that, to gain full benefit from the book, you’d probably need to be about 1800+ strength and prepared to take the book seriously, reading it with a chessboard at your side, covering up the text and attempting to solve the exercises yourself.

We’ve all seen games where Capablanca, for example, wins without having to resort to complex tactics, because his opponents are far too late to catch onto what’s happening. I could well imagine a book written for players of, say, 1400-1800 strength featuring this type of game, perhaps with some more recent examples. There must be many games from Swiss tournaments where GMs beat amateurs in this way.

I have a few minor criticisms:

- While I understand that publishers want to save paper, I’d have preferred each example to start on a new page

- There is some inconsistency as to whether or not we’re shown the opening moves before the exercises start. I’d have preferred to see the complete game in all examples.

- There are a few shorter examples, lasting only a few moves, in the final chapter which seem rather out of place and might have been omitted.

- The games disproportionately favour White: I’d have preferred a more equal balance between white and black wins.

- Some of the ‘exercises’, it seems to me, are mistakenly labelled as ‘questions’. The first question/exercise in Game 1 is an example.

- Names of Chinese players are sometimes given incorrectly: for instance, Bu Xiangzhi appears both in the text and the index as B. Xiangzhi. Bu is his family name and Xiangzhi his given name, and Chinese names are customarily printed in full. Failure to do so (and the book is inconsistent in this) seems to me rather disrespectful.

In spite of these resservations I can recommend the book very highly as a collection of excellent and often beautiful top level games with first rate annotations. Stronger club standard players, in particular, will find it helpful in improving not just their planning skills but their tactical skills as well.

I really enjoyed reading it and I’m sure you will as well.

Richard James, Twickenham, 20th January, 2020

Book Details :

- Paperback : 416 pages

- Publisher: Everyman Chess (1 Sept. 2019)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1781945373

- ISBN-13: 978-1781945377

- Product Dimensions: 17.1 x 2.3 x 23.8 cm

Official web site of Everyman Chess