The 6th Keith Richardson Memorial Tournament took place on Saturday, September 24th at Camberley Baptist Church and was organised by Camberley Chess Club.

Category Archives: 2022

Minor Pieces 45: Jessie Helena (Hume) Cousins

You might have noticed that all the Minor Pieces to date have featured gentlemen. The main reason, I suppose, is that most of them have been about members of early chess clubs in the Richmond and Twickenham area which specifically advertised as being for gentlemen. No ladies, and certainly no plebs.

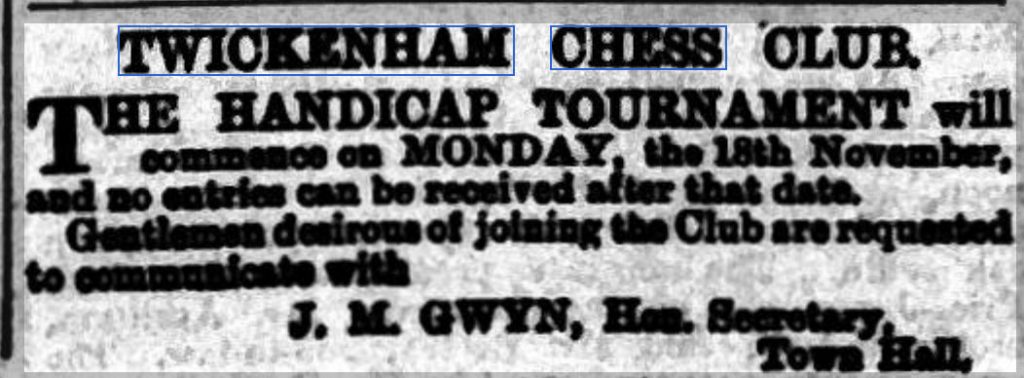

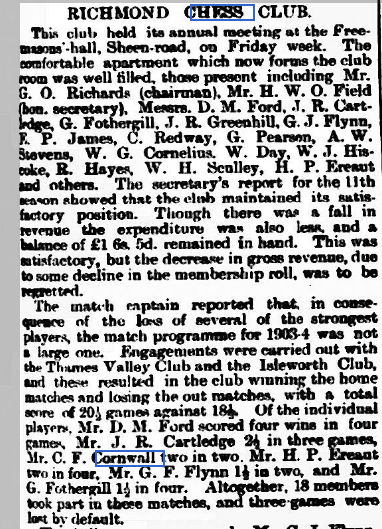

Here’s Twickenham Chess Club, for example, although a slightly later report of a Richmond Chess Club AGM mentioned that they had a couple of lady members: seemingly social rather than match players.

But there was also a very popular and successful Ladies Chess Club founded in London in 1895. We’ll meet some of their members in future articles. In 1904 the first British Championships incorporated a Ladies Championship. It’s clear that round about 1900, although the majority of competitive players were, just as today, male, chess for ladies was also thriving. It will be interesting to find out who they were and how (and why) they played the game of queens as well as kings.

But first you might have spotted one of PGL Fothergill’s Staines and Ashford teammates in a recent article.

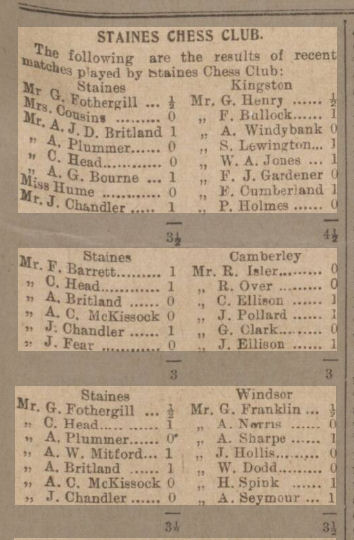

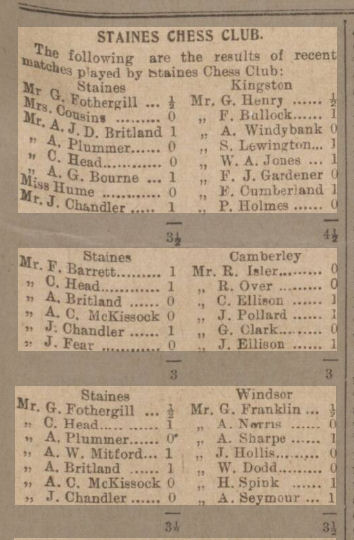

The Staines team playing Kingston featured not just Mrs Cousins but Miss Hume as well.

She was still playing after the First World War, when Staines had possibly been renamed Ashford and District.

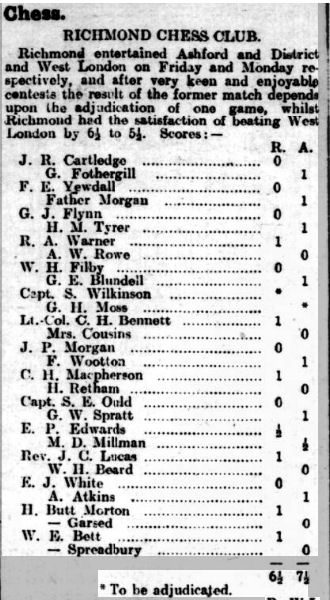

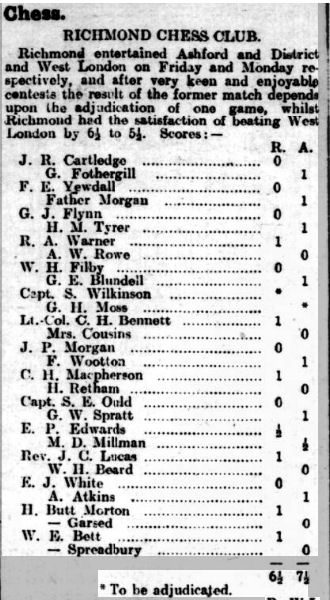

Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Henry Bennett (1853-1925) had been born in Cork and spent his career in the Indian Army Medical Service, also serving in Afghanistan. His gallantry didn’t extend to letting his lady opponent win the game.

So, who was Mrs Cousins and what was she doing in a man’s – sorry, gentleman’s – world?

She was born Jessie Helena Hume in St Marylebone on 28 June 1866, so she was in her 40s and 50s when playing in these matches. Her father, Charles Dobinson Hume, was a clerk working for the local government board, whose work involved with the Poor Law would take him to Ashford, Middlesex. Her mother, presumably, was Catherine Austen Mary Bailey, whose second name suggests her parents may have been Janeites. Although Jessie’s birth was registered (as Jessie Helen) with the surname Hume and mother’s maiden name Bailey, her parents weren’t married at the time, and were living separately in 1871, Charles with his parents and Catherine working as a bookkeeper, described as a servant to an accountant. They only married – in Richmond – in 1872 (with Catherine’s name given as Kate), at which time they moved to Ashford. I haven’t yet been able to locate Jessie in the 1871 census as either Hume or Bailey – she may well have been living with relations. Once Charles and Kate had tied the knot, four more daughters arrived: Mabel in 1874, twins Edith and Sophia in 1876 and finally Isabel in 1877.

I can’t find any immediate connection with the Scottish born problemist George Hume.

I presume Jessie learnt chess from her father, although he doesn’t seem to have been a competitive player. Miss Hume in 1914 would have been one of her sisters: Sophia had married by this point, but Mabel, Edith and Isabel were all unmarried and living at home with their widowed mother, so it might have been any of them. It’s both strange and annoying that, in those days, ladies’ names were given only with a title, not an initial.

Jessie had married Thomas George Cousins in Staines in 1893: they went on to have five children between 1895 and 1909: Dorothy, Sydney, Lillian, Dennis and Margaret. Thomas would have known his father-in-law through work: he was the Relieving Officer for the Guardians of the Poor of Staines Union – the workhouse. His job would have involved assessing the needs of the poor in the area and providing for them to the best of his ability.

At some point she took up correspondence chess. Thanks to Gerard Killoran for sending me this game, taken from the Weekly Irish Times (21 August 1909). Her opponent appears to have been Arthur Patrick Morgan (1864-1918), a school inspector. Jessie played the first part of the game very well, but unfortunately missed the opportunity to win the exchange on move 35. The newspaper commented: A well played game by “one of the gentler sex”. All through most interesting, but Mr Morgan had the most experience. The ending is rather unexpected. Click on any move for a pop-up window.

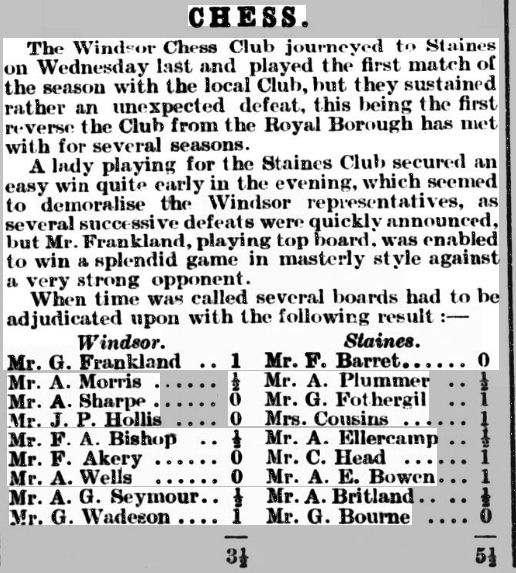

It’s not yet clear when Staines Chess Club was founded. I can’t find any earlier mentions than this 1913 match against Windsor, but it’s quite possible the relevant local newspapers aren’t yet available online.

Today, I’d imagine a female chess player would feel insulted and patronised to be discussed in that way, but I suspect that, in those very different times, Mrs Cousins was more likely to have been flattered and amused.

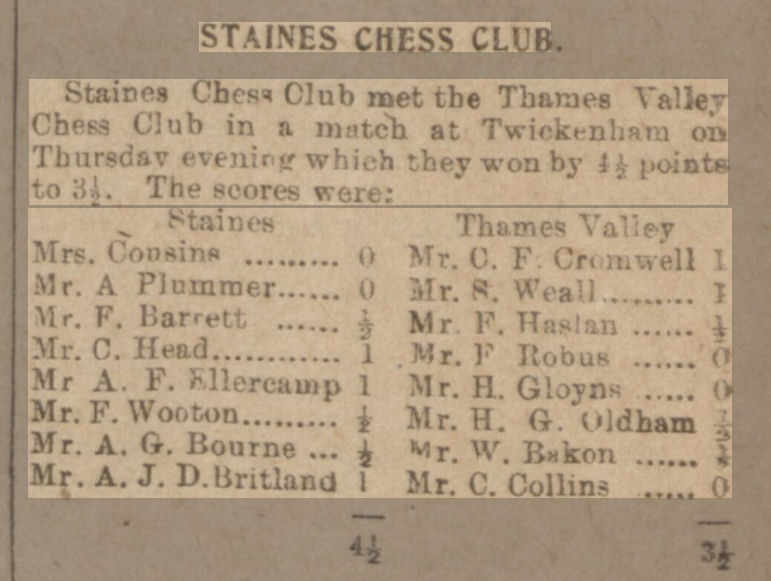

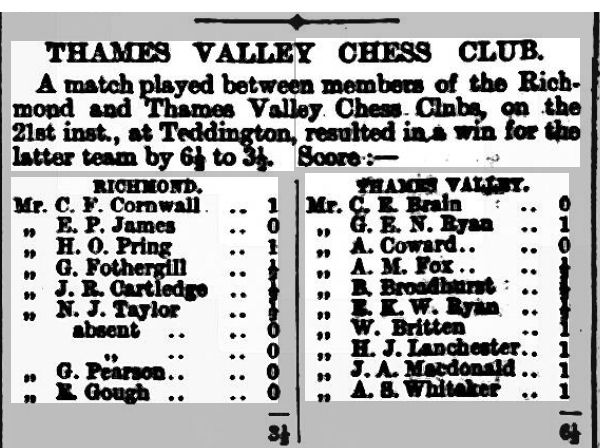

The selectors must have been impressed with her speedy victory, as, a few months later, she was promoted to top board in this match against Thames Valley.

CF Cromwell must have been a misprint for Cecil Frank Cornwall: he was a pretty strong player so it was no disgrace to lose to him.

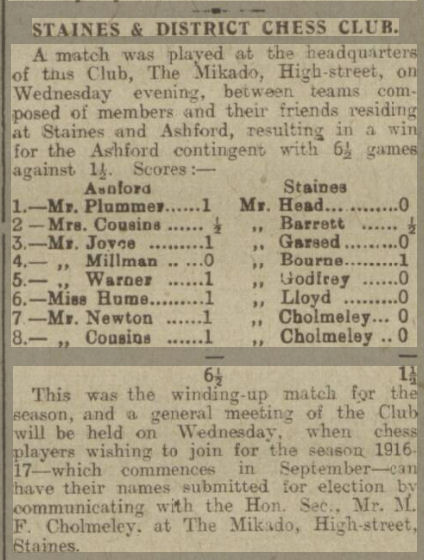

Just as Richmond Chess Club staged matches between the residents of Richmond and Sheen, so Staines (now Staines and District) Chess Club staged matches between the residents of Staines and Ashford. In this wartime match, Jessie’s sister (the same one as above?) and husband were both successful. Did she, I wonder, teach her husband how to play?

Their Club Secretary, Montague Francis Cholmeley, from the family of the Cholmeley Baronets, don’t you know, was born in what was then Madras in 1856 and died in Staines in 1944. Not many people outside the area know that Staines was the home of linoleum for more than a century from its invention in 1860, and the Staines Linoleum Company employed Monty, a solicitor, to deal with their legal affairs. I’m not sure who the other Mr Cholmeley was. His only brother was in India. It might, I suppose, have been his son Humphrey Jasper, home on leave from the trenches, where, on 15 July the same year, he tragically lost his life in the Battle of the Somme. I assume the Mikado was a restaurant: it would have been a very short walk from where, a few years later, the Misses Ada and Louisa Padbury would be juggling running their own restaurant with bringing up their young niece. Yes, you’ve heard the story before, and you’ll hear it again as well.

I’d imagine, then, that at some point fairly soon after this match the club moved down the road to Ashford, the home town of its stronger members, changing its name in the process, taking us to 1921, when we saw Jessie Cousins playing in a match against Richmond.

Also in 1921 she played on board 183 for the North of the Thames in a 400 board megamatch against the South of the Thames: you can see the full score here. You’ll note that the two players immedately above here were Staines/Ashford colleagues. There are some great names on both sides in this match, including the subject of the next Minor Piece. I should perhaps look in more detail another time: meanwhile there’s some background information here.

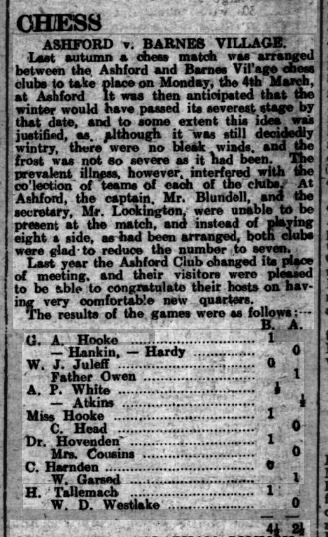

Richmond, as we’ll see, faced competition in the area from new clubs in Twickenham (you’ll recall the previous Twickenham club had moved to Teddington and changed its name to Thames Valley), Barnes and Kew. I’ll tell you more about the Barnes Village chess club next time, but in the inter-war years they played regular matches against Ashford.

This, from 1929, is the last mention of Mrs Cousins I’ve been able to find.

You’ll see that both teams fielded a lady, and they just missed each other by one board: Miss Hooke (in 1929 ladies were still not allowed initials) was playing for Barnes Village along with GA Hooke. You’ll find out more about the Hooke family very soon.

The 1939 Register records Thomas, Jessie and their unmarried daughter Dorothy living at 18 Fordbridge Road, Ashford, Middlesex, which is where Jessie died on 23 August 1948 at the age of 82. I haven’t found any records of any of her children playing competitive chess.

Jessie Helena (Hume) Cousins was a lady who, for almost two decades, was successful in the, then as now, male dominated world of suburban competitive chess. She was clearly a more than competent player as well, probably around 1800 strength by today’s standards. Her story should be an inspiration for any girls and women wanting to take up competitive chess today.

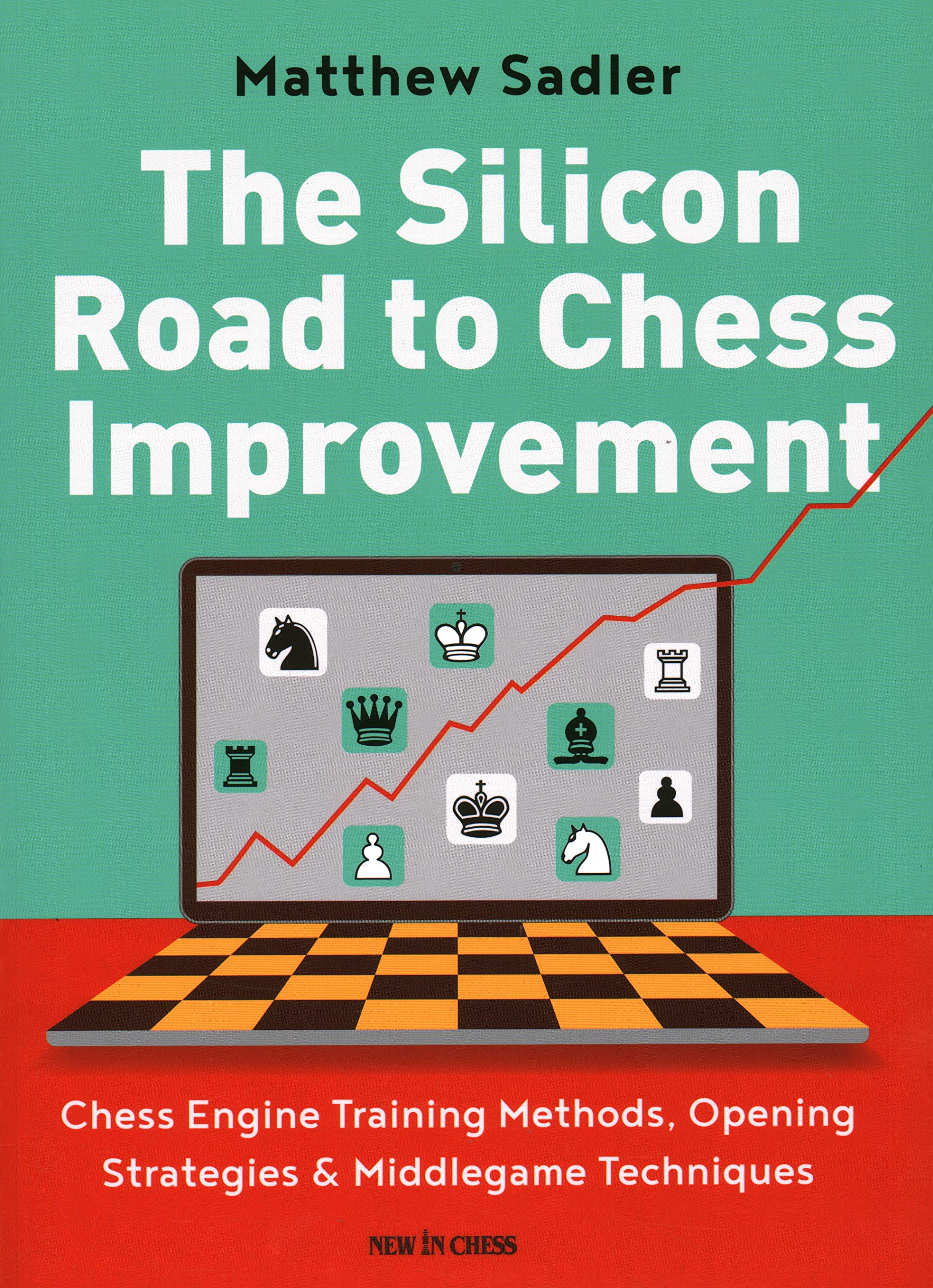

The Silicon Road To Chess Improvement: Chess Engine Training Methods, Opening Strategies & Middlegame Techniques

Here is the publishers blurb from the rear cover :

“Every chess player, from club level up, can improve their game by using engines. That is the message of Matthew Sadler’s thought-provoking new book, based on many years of experience with the world’s best chess software.

You may not be able to replicate their dazzling-deep calculations, but there is so much more your engine can do for you than just checking variations! Matthew Sadler, co-author of the ground-breaking bestseller Game Changer, presents some unique methods to improve by using your engine. He explains how in your opening preparation, instead of sifting through masses of computer analysis you should play training games against your engine. He also shows how to train your early middlegame play, the conversion of advantages, your positional play, and your defensive skills. And, of course: how to analyse your own games.

These generic training methods Sadler supplements with concrete techniques. He explains how the top engines tackle crucial middlegame themes such as entrenched pieces, whole board play, ‘attacking rhythm’, exchanging pieces, the march of the Rook’s pawn, queen versus pieces, and many others. He also opens your eyes to typical strategies that the engines found and fine-tuned in popular openings such as the King’s Indian, the Grünfeld, the Slav, the French and the Sicilian. Sadler illustrates his lessons with a collection of fantastic games, explained with his trademark enthusiasm. For the first time, the superhuman powers of the chess engine have been decoded to the benefit of all players, in a rich and highly instructive book.”

About the author :

Matthew Sadler (1974) is a Grandmaster and a former British Champion. He has been writing the famous ‘Sadler on Books’ column for New In Chess magazine for many years. With his co-author Natasha Regan, Sadler twice won the prestigious English Chess Federation Book of the Year Award. In 2016 for ‘Chess for Life’ and in 2019 for their worldwide bestseller Game Changer: AlphaZero’s Ground-breaking Chess Strategies and the Promise of AI.

This is the latest book by acclaimed author and 2 time British Champion Matthew Sadler. His previous book Game Changer: AlphaZero’s Groundbreaking Chess Strategies and the Promise of AI (co-authored with Natasha Reagan) won both the 2019 ECF Book of the Year and FIDE Book of the Year. Following the publication of Game Changer the authors gave many talks around the country about Alpha Zero. They were frequently asked the same two questions “what could be learnt from AlphaZero’s games and were they too advanced for us mere mortals?” This book sets out to show that there is a considerable amount that can be learnt from these computer engine games as well as discovering many new ideas that can be extracted and applied in one’s own games. The author also sets out to demonstrate that every chess player from Club level upwards can improve with the help of chess engines as the engines can do much more than just calculate variations. Chess engines can be used to enhance opening preparation and to improve your skills in the middlegame. This book can be thought of as a sequel to Game Changer but it can also be read independently as it showcases the games played by all the top computer engines rather than focusing on the radical changes brought about by AlphaZero.

The book is split into two parts. The first part provides an overview of todays top chess engines and the associated training methods recommended by the author. This covers the methods that the author has employed as a professional player as well as some new and innovative ways to using chess engines. Part 2 contains the meat of the book, 18 chapters & 484 pages analysing a wide range of opening and middlegame themes. To assist the reader, there is also some supporting Supplementary Material available to download. This includes a PGN file containing all the games included in the book together with instructions on how to set up and configure the chess engines. Having downloaded everything I found the instructions easy to follow and anyone with a moderate level of IT skills should to be able to do the same. The author has also recently created a YouTube channel: SiliconRoadChess which contains over 250 videos showing how to use chess engines and showcasing the best engine games. As well as covering topics such as Engine Openings (92 Videos) and Great Engine Games (74 videos) there are many other interesting videos to watch from TCEC events and analysis of some of the games from the recent Carlsen Nepomniachtchi match. As well as the videos there is also a PGN database available providing additional material for the channel. Currently there are over 2.21 K subscribers to Silicon Road but I am sure that this number will increase. After watching a few of these videos it is clear that Matthew’s has a passion and enthusiasm for engine chess and I shall be watching many more of these in the weeks to come.

The first two chapters in part 1 are an introduction into the world of computer chess and the Top Chess Engine Competition (TCEC) which is the source for most of the games in this book, the remainder were generated by the author himself. We are introduced to the top engines (our heroes) together with a description of their playing styles, strengths, weaknesses and associated technical notes.

In chapter 3 the author lays out the methods that he has used himself to study with chess engines during his career along with a couple of new and innovative approaches. These are as follows:

- Playing Rapid Games – Good for opening and early middlegame play.

- Playing against Leela Zero restricted to a one-node search. – Good for openings, positional play and conversion of winning positions.

- Playing out positions with a rapid time control. – Good for conversion of advantages and developing defensive skills

- Playing ‘correspondence chess’ against your engine. – Good for developing analytical skills and conversion of advantages.

- Running engine matches from key opening positions. – Good for developing a feel for openings and related middlegames.

- Letting your engines analyse an opening position for X hours (deep analysis). – Good for analysing a single position in great depth.

- Periodic checking of your analysis against a live engine – Develops a real-time insight into a position

Like most players I have used computer engines in the past for analysing my own games and as a sparring partner, mainly using Fritz on only the lower handicap levels. Up until now I have not used the methods described above apart from the first and the last one. So I decided to try out a couple of other methods for myself. I began with method 5, playing engine matches from key positions and get an overview of specific openings. I won’t go into too much detail here as it would give away how the author has used this method but I tried out the approach on two types of openings. Firstly I used it on some lesser known gambits. The rationale being that firstly I have never played these openings and that they are difficult to learn. Not only are there are a many variations to memorise but also there are a lot of critical positions to evaluate. Secondly I chose selection of positional openings to see how the engines would get on. I used a number of different engines (Stockfish 15, Deep Fritz 13, Fat Fritz & Leela v22) running on an i5 Laptop and a time control of M20 + 5 second increments. The matches were set up to play 6 games in each opening. (I did run a number of matches with Blitz time controls but the results were not as good) Running these matches with Cloud Engines or longer time controls would of course produce better quality games. I chose the following three gambits:

- The Henning-Schara Gambit (1 d4 d5, 2 c4 e6, 3 Nc3 c5. 4 cd cd )

- The Marshall Gambit in the Semi Slav (1 d4 d5, 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 e6 4 e4)

- The Portsmouth Gambit (1e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 b4)

And for the ‘positional’ openings I used:

- The Ruy Lopez Exchange Variation and the Berlin Defence

- Queens Gambit Accepted and Exchange variations.

- Italian Game with c3 & d3

The Ruy Lopez Berlin Defence (aka Berlin Wall) has proved to be a very efficient drawing weapon since it was made ‘popular’ by Vladimir Kramnik back in 2000. It is also an opening that engines consider as best play with both colours. (For a more detailed explanation see: Engine Openings Understanding the Ruy Lopez Berlin which also includes the author demonstrating how to take on Leela Zero in the 1-node mode described above.) Once all the engine matches were completed I was pleasantly surprised to find out how much I learnt by just by playing through the engine games. This approach will not make you an instant expert and would only be a prelude to more detailed study but it will be something that I will definitely use in the future. I will also use this approach in conjunction with method 6 to examine some of the critical positions in more detail. I have not included the results of the matches are they are not important as I was not trying to determine which engine was the strongest but only interested in the games that the engines produced.

To give you some idea of the quality of the games here is an example game from the Portsmouth Gambit match played between Stockfish 15 and Leela 0 v22.

Stockfish 15 – Lc0 v0.22.0 cpu [B30] Rapid 20.0min+5.0sec

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.b4 Nxb4 4.c3 Nc6 5.d4 cxd4 6.cxd4 e6 7.Nc3 Bb4 8.Bd2 d5 9.e5 Nge7 10.Bd3 Qa5 11.Rc1 Bd7 12.0-0 h6 13.Nb5 0-0

14.Bxh6 gxh6 15.a3 Bxa3 16.Ra1 f5 17.Rxa3 Qb6 18.Rb3 Na5 19.Rb1 Bxb5 20.Rxb5 Qc7 21.Qd2 Nec6 22.Qxh6 Rae8 23.g4 Qg7 24.Qxg7+ Kxg7 25.gxf5 exf5 26.Rd1 a6 27.Rxd5 Rd8 28.Rxd8 Rxd8 29.Bxf5 Nc4 30.Ng5 Nxd4 31.Rxd4 Rxd4 32.Ne6+ Kh6 33.Nxd4 Na5 34.f4 1-0

A fascinating combination beginning with the bishop sacrifice on h6 immediately followed by pawn sacrifice on a3 then finally 21 Qd2 with a double attack on h6 & a5. There is a whole chapter in the book devoted to the concept of whole board play and this game is an excellent demonstration of this theme.

I also tried out method 2, playing some games against Leela Zero in 1-Node mode. This approach restricts Leela Zero to a single node (looking one move ahead) instead of the usual millions of nodes per move. Leela Zero is so good that its first choice move is usually good enough for high level of play. Also, when playing in 1-node mode the engine moves are made instantly. The only weakness that I found with this approach was that is that the engine does not see any tactics. However this is a blessing in disguise as it replicates ‘human’ play as the engine plays a series of good moves followed by the occasional blunder. Having played a number of games against Leela Zero in this mode I can see the benefits of using this approach. I was really impressed with the quality of play considering the engine is only looking one move ahead. You can try playing against Fritz in one of the ‘handicap’ modes and get similar results but the Leela Zero engine and Nibbler GUI are both available as free open source alternatives.

Part 2 is devoted to the author’s research into chess engine games. This covers the identification of the recurring middlegame themes and highlighting the exceptional games that contain these ideas. Sixteen different themes are covered. The games in this section have been analysed very deeply and the author explains his approach which is as follows:

- An initial analysis of each game without any engine assistance.

- Checking the analysis with live engine help

- Identifying interesting points in the game to be investigated further (typically between 10 -15)

- Run an engine match on all the positions of interest (anything from 40 -120 games)

- Pick out the key games and add to the original analysis

- Iterate until all above questions have been resolved

- Distil and summarise all the above information into the game annotations

Also at the beginning of Part 2 there is a chapter covering the typical opening scenarios covered in the book from the following openings: Kings Indian Defence, Grunfeld, Slav & Semi Slav, English and the French Defence.

One chapter is devoted to a specific middlegame theme and each theme is discussed with a selection of annotated engine games followed by a deeply annotated illustrative game. The analysis of these illustrative games is incredibly deep and several run to over 20 pages! Amongst the topics covered here are exchanging active pieces to leave the opponent with passive ones, the march of the rooks pawn (one of the major discoveries from Alpha Zeros games), Engine Sacrifices, Whole Board Play and the Kings Indian Opposite Wing Pawn Storm. The final chapter discusses how best to apply the themes in your own games. The author also describes one of the most memorable moment in his chess career was when he first had an opportunity to play through hundreds of AlphaZero Stockfish games. Specifically the number of high quality games that were produced. He thought that this was more memorable than any of his OTB achievements (which included winning the British championship and representing England in the Olympiads).

This has been a fascinating book to review. Previously I had not paid a great deal of attention to computer chess in the past, either because I didn’t think it was relevant to OTB play or the games were far too difficult to understand. The author clearly has a very deep understanding of computer chess and has done a tremendous amount of research analysing engine games, identifying and classifying the recurring patterns contained therein, then showing how this knowledge can be applied taken to your own games. As well as reading the book I took the opportunity to watch many of the videos on the associated YouTube channel. The majority of which have been produced since the book was first published in 2021. No doubt many more videos produced in the future. Although this is a large book (560 pages) it is not ‘heavy’ book to read. Some of the topics in part 2 are very complex but the author explains them all in a clear and concise manner. The more that I find out about this subject the more interesting it becomes. So if you have ever wanted to find out more about the fascinating world of computer chess and how to use the engines to improve your own game then this is a good place to start. I highly recommend buying this book.

Tony Williams, Newport, Isle of Wight, 21st September 2022

Book Details :

- Paperback : 560 pages

- Publisher:New In chess (31 December 2021)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9056919830

- ISBN-13:978-9056919832

- Product Dimensions: 17.17 x 2.11 x 23.67 cm

Official web site of Everyman Chess

Minor Pieces 44: Henry Jones Lanchester

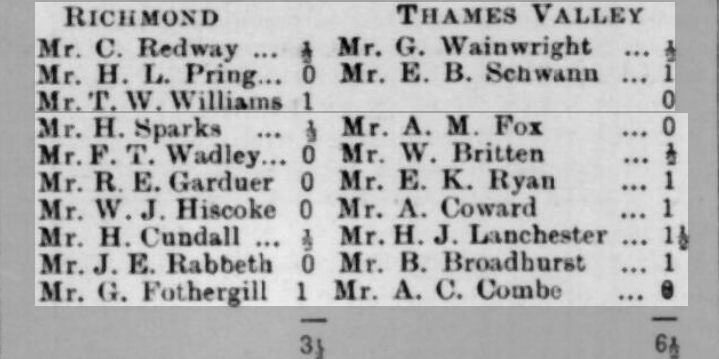

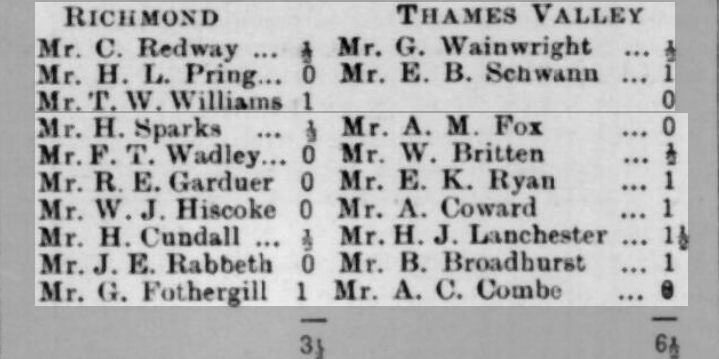

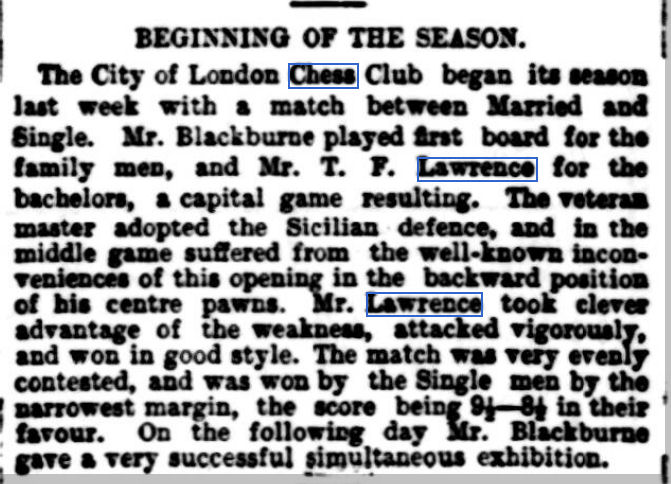

You might have seen this in the previous Minor Piece. Consider for a moment the Thames Valley team. There on board 6 or thereabouts is Arthur Coward, father of Noël. A board (or possibly two) below him is Mr HJ Lanchester, another man with an interesting family. (I note, en passant, that Augustus Campbell Combe on board 10, a Stock Exchange Clerk, was Wallce Britten‘s brother-in-law.)

Henry Jones Lanchester was an architect and surveyor, born in Islington on 5 January 1834, so he was 65 at the time of this match.

He lived at various addresses in London before moving to Brighton in about 1870, where he worked on the Stanford Estate and Palmeira Mansions. But he was badly affected by the property slump of the late 1880s and moved back to London with his family, settling in Battersea, not far from Clapham Common.

The good news for Henry was that he now had more time to play chess and immediately joined Balham Chess Club, where he won 2nd prize in their 1888-89 tournament and played on a high board for them in matches against neighbouring clubs as well as being selected to represent Surrey in county matches.

By 1895 he’d moved to a house called Salvadore on Kingston Hill, and the 1901 census found him at Ripley House, Acacia Road, New Malden, on the same estate as Richmond top board IM Gavin Wall, not to mention David Heaton. Living close to the station, it would have been easy for him to catch the train to Teddington to play for Thames Valley Chess Club, unless he preferred a ride in one of those new-fangled motor cars.

But Thames Valley wasn’t his only chess club: he was also playing for Surbiton. Here he is, in 1901, taking second board in two matches and gallantly agreeing a draw against Mrs Donald Anderson of the Ladies Chess Club in a favourable position. Mrs Anderson (née Gertrude Alison Field) won the British Ladies Championship in 1909 and 1912, so this was a good result.

In 1903 he had a wasted journey to Richmond as, all too typically for the home club at the time, two of their players failed to turn up. Didn’t they have any social players there to fill in? Fortunately, our excellent match captains are far better organised today.

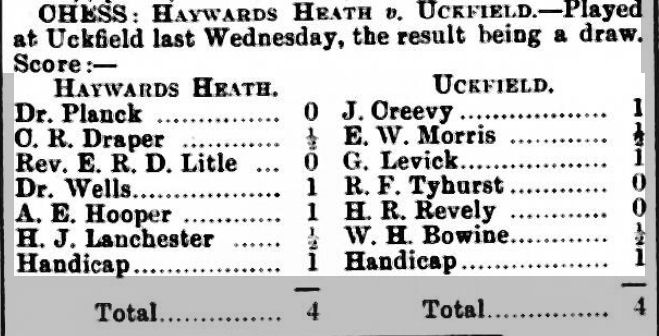

By the middle of the decade he had returned to Sussex, settling in Lindfield, near Haywards Heath, whose chess club he promptly joined

Here’s a 1906 match card.

I’m not sure why both teams scored a Handicap point on board 7, but there you go.

Haywards Heath’s top board, Dr Charles Planck (no relation, as far as I know, to Max), was a doctor and psychiatrist running the local lunatic asylum, a type of institution with which Lanchester, as you’ll find out later, had had previous experience. He was also one of England’s leading problemists, having co-authored, back in 1887, a book called The Chess Problem with fellow problemists Henry John Clinton Andrews, Edward Nathan Frankenstein and Benjamin Glover Laws. Another spoiler alert: read on for a very different Frankenstein.

Henry Jones Lanchester also played correspondence chess, playing for Sussex in matches against other counties. He died at his home in 1914, on his 80th birthday.

Here’s a game from one of those correspondence matches. His opponent was born Emily Beetles Nicholls in Guildford in 1872. Her father, Edward, was high up in the Inland Revenue and seemed to move around the country a lot. Click on any move for a pop-up board.

Probably not a game which showed him at his best. The Vienna Game is devastating against an unprepared opponent and his natural third move just leads to a lost position, 6. d5 would have been much better than Mrs Bush’s e5, which allowed Henry back into the game. (Thanks to Brian Denman for sending me this, which was published in the Lowestoft Journal (23 Jan 1909).)

Here, then, was a man who must have played chess all his life, but, it seems, only took up competitive chess on his retirement (or perhaps semi-retirement) from his career as an architect and surveyor.

For further information on Henry Jones Lanchester:

Wikipedia

Grace’s Guide (also links to his sons)

He must also have taught his children chess. Some of them had very interesting lives.

Henry had married Octavia Ward, a mathematics and Latin tutor, in 1863. Their children were Henry Vaughan (1863), Mary (1864), Eleanor Caroline (1866), Frederick William, known as Fred (1868), Francis, known as Frank (1870: his twin brother Charles didn’t survive), Edith, known as Biddy (1871), Edward Norman (1873) and George Herbert (1874). Henry junior became, like his father, an distinguished architect. Mary and Eleanor both became artists. Edward emigrated to New Zealand, later moving to Australia and earning a living as a signwriter.

The other three brothers, Fred, Frank and George, were a lot more interesting.

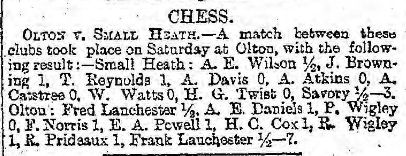

Fred Lanchester was one of the most remarkable engineers and inventors of his time. In 1888 he took a job with a gas engine company in Birmingham, and, in his spare time, started working on designing motor cars. In 1895 he completed a four-wheeled vehicle powered by a petrol engine. In between his work and his vehicle, he also found time to play chess. Here he is, playing on top board for his local club, Olton (near Solihull), with his brother Frank, clearly an inferior player, on bottom board.,

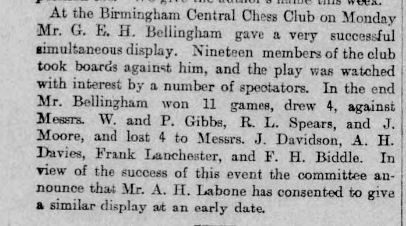

In 1898, he won a game in a simul against the leading West Midlands player of his day, George Edward Horton Bellingham. You’ll notice an incorrectly initialled mention of our old friend Oliver Harcourt Labone.

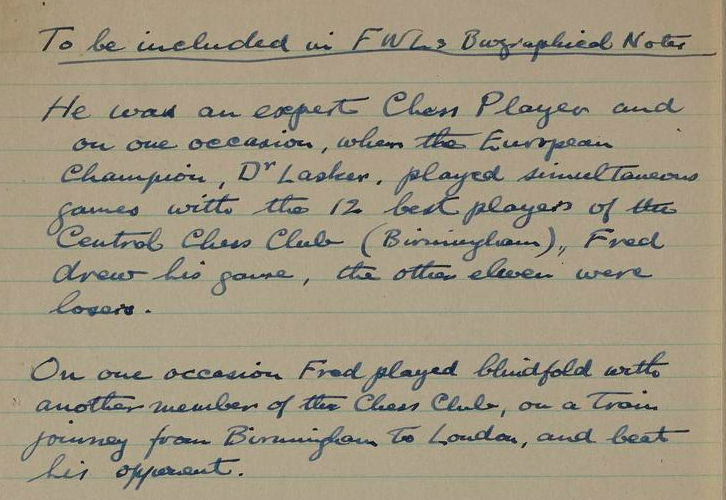

According to his brother George he also beat none other than Emanuel Lasker in a simul.

However, George’s account doesn’t tally with any of the Lasker simuls given by Richard Forster in his definitive list here.

| 1 Mar 1897 | Birmingham | 31 | 26 | 3 | 2 | |

| 2 Mar 1897 | Birmingham (consultation) | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 Dec 1898 | Birmingham, Central C.C. | 25 | 13 | 9 | 1 | Various games were adjudicated, two left undecided. |

| 23 Nov 1900 | Birmingham, Temperance Institute | c10 | c10 | 0 | 0 | Vlastimil Fiala in the Quarter for Chess History, no. 6/2000, pp. 382f. claimed a score of 25 wins, but it was not possible to verify this score indepedently. The Cheltenham Examiner, 28 November 1900, indicated “less than a dozen” and the Birmingham Weekly Post, 1 December 1900, spoke of “a meagre attendance”. |

| 17 Mar 1908 | Birmingham C.C. | 28 | 23 | 3 | 2 |

In December 1899 Fred, Frank and George created the Lanchester Engine Company to build and sell motor cars to the general public. George was also a brilliant engineer, while Frank was the sales manager. For several decades Lanchester was one of the most famous makes of motor car in the country.

The name Lanchester was commemorated in 1970 with the creation of Lanchester Polytechnic, now Coventry University.

Perhaps the family’s achievements, especially those of Fred, are unfairly forgotten today. They certainly deserve to be remembered as pioneers of the early motor car industry. It’s good to know that Fred was also a pretty good chess player.

For more information on the Lanchester brothers:

Wikipedia (Fred)

Wikipedia (George)

Wikipedia (Lanchester Motor Company)

Lanchester Interactive Archive

Their sister Edith (Biddy) was another matter entirely.

Biddy became a socialist and suffragette, living ‘in sin’ (as they used to say) with a working-class Irishman named James ‘Shamus’ Sullivan: the couple both disapproved of the institution of marriage.

Horrified by this, in 1895 her father and brothers kidnapped her and sent her to the lunatic asylum (it’s now, famously, The Priory) on the grounds that only an insane person could possibly become a socialist. The asylum could find nothing wrong with her and released her a couple of days later. In 1897 she became Eleanor Marx’s secretary. The job didn’t last long as Eleanor committed suicide the following year. Perhaps Biddy and Eleanor also played chess: I’d imagine Biddy learnt the moves from her father and brothers, and Eleanor usually beat her father (Karl, of course) at chess.

Biddy and Shamus’s first child, a son called Waldo, was born in 1897. He became a famous puppeteer, founding the Lanchester marionettes, a puppet theatre which ran from 1935 to 1962.

Their second child, a daughter whom they named Elsa, was born in 1902. Elsa took up dancing as a child, then worked in theatre and cabaret, also obtaining small roles in films.

In 1927 she married the actor Charles Laughton and, after playing Anne of Cleves to his Henry in The Private Life of Henry VIII, the couple moved to Hollywood where Elsa found fame in 1935 for her starring role in The Bride of Frankenstein. (Be careful not to confuse her with Miriam Samuel, the bride of the aforementioned Edward Nathan Frankenstein.) Elsa continued to perform on the silver screen, mostly in cameo roles, up to 1980, including playing Katie Nanna in Mary Poppins.

Of course, there’s something you all want to know. Did Elsa, like her grandfather and uncles, play chess. Why yes, she certainly did. VIctoria Worsley’s recent (2021) biography, Always the Bride, tells of her playing chess with a friend on a car journey in 1936. Chess wasn’t her only game, either. Here she is playing draughts against Charles Laughton.

As Elsa’s grandfather played chess on the adjacent board to Noël Coward’s father, you might also want to know whether they ever appeared in the same film. Sadly not, although Coward provided some dialogue for the 1957 Agatha Christie adaptation Witness for the Prosecution, starring Tyrone Power and Marlene Dietrich along with Laughton and Lanchester. (Elsa won a Golden Globe award for the Best Supporting Actress in a Motion Picture.)

More about Biddy and Elsa:

Wikipedia (Biddy)

Wikipedia (Elsa)

IMDb (Elsa)

This was the life and chess career of Henry Jones Lanchester, a man who shared a mutual friend with Frankenstein, and whose granddaugher was the Bride of Frankenstein. Henry was also the head of a remarkable chess-playing family, pioneers in both motoring and movies.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Wikipedia

Grace’s Guide

IMDb

Lanchester Interactive Archive

Other sources mentioned in the text

Richard Forster: Lasker’s Simultaneous Exhibitions. www.emanuellasker.online (2022).

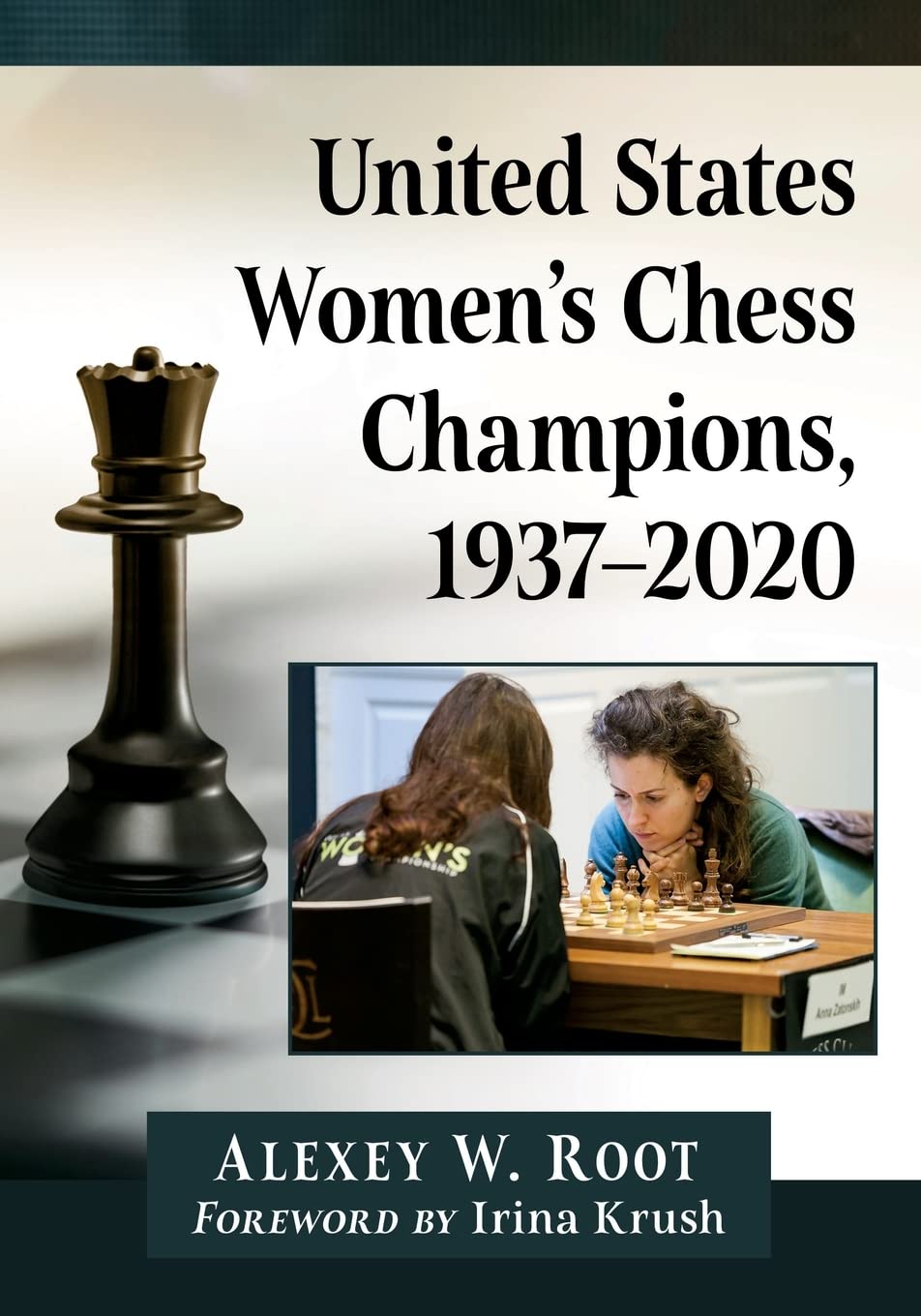

United States Women’s Chess Champions, 1937–2020

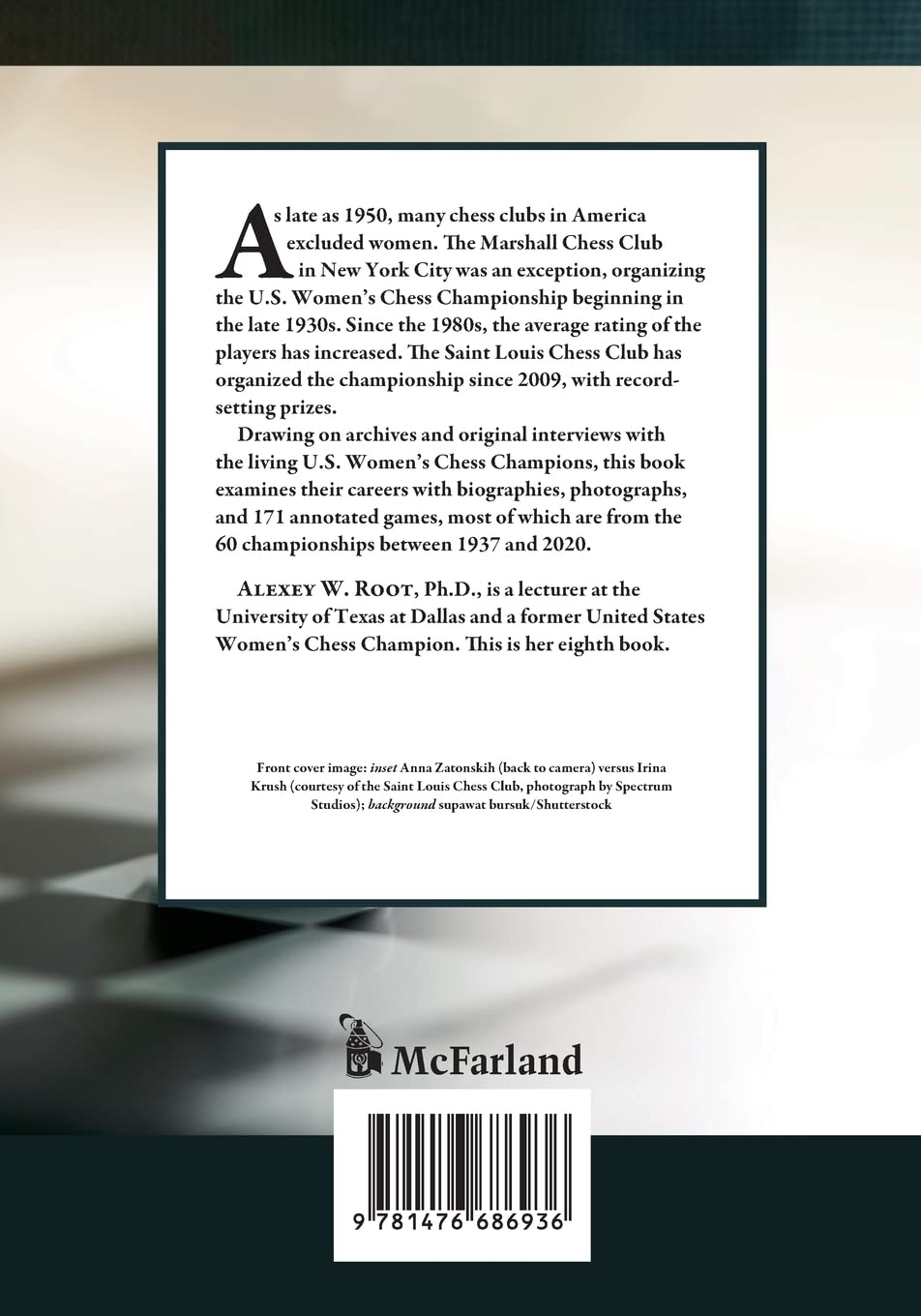

From the publisher’s blurb:

“As late as 1950, many chess clubs in America excluded women. The Marshall Chess Club in New York City was an exception, organizing the U.S. Women’s Chess Championship beginning in the late 1930s. Since the 1980s, the average rating of the players has increased. The Saint Louis Chess Club has organized the championship since 2009, with record-setting prizes. Drawing on archives and original interviews with the living U.S. Women’s Chess Champions, this book examines their careers with biographies, photos, and 171 annotated games, most of which are from the 60 championships between 1937 and 2020.”

“Alexey W. Root, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the University of Texas at Dallas and a former United States Women’s Chess Champion. This is her eighth book.”

For many years chess was traditionally seen as a game for white males, and, in these days where representation is considered so important, there is much that needs to be written about other aspects of the game.

In particular, it’s important that the history of women’s chess is written, that stories are told, that games are published. So it’s a particular pleasure to welcome this new book by former US Women’s Champion Alexey Root, featuring every champion from 1937 to 2020.

We have 29 chapters in total, one for each champion, with winners of multiple titles granted more space. Some of the recent winners will be well known to many readers, but many of the earlier champions will have names only remembered by those who enjoy digging around in chess archives.

In each chapter you’ll learn about their lives both within and outside chess as well as seeing some of their games, all with light annotations. Each chapter also includes a photograph of its protagonist. The book has been thoroughly researched, and all living champions were asked to assist: advising on games and, on occasion, providing scoresheets and photographs.

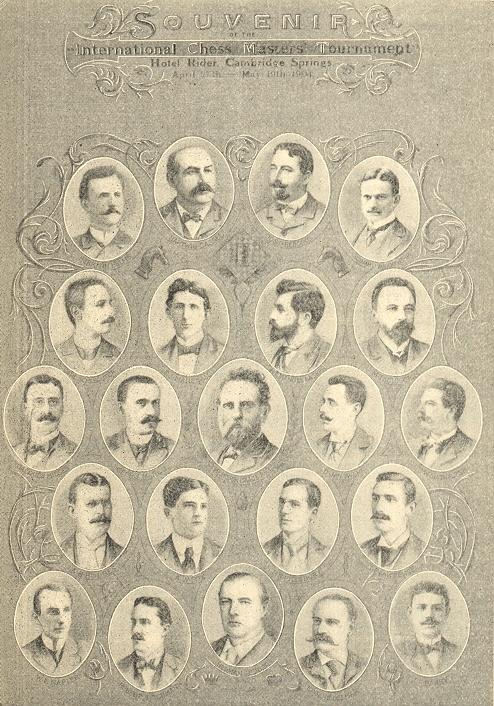

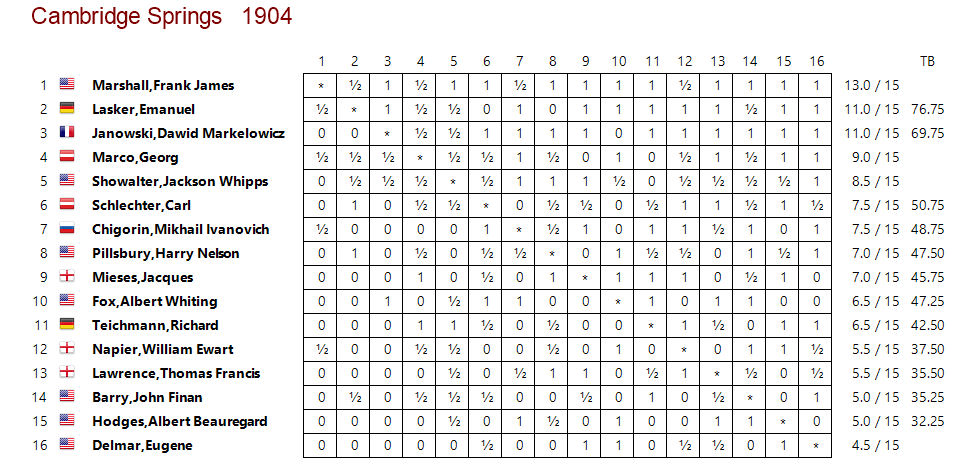

Whereas the first British Championship took place back in 1904, with the British Ladies Championship incorporated in the congress, the first US Women’s Championship didn’t happen until 1937, hosted by the Marshall Chess Club. In fact, the first US Championship tournament only took place the previous year, the title having up to that point been decided by challenge matches.

The first champion was Adele Rivero Belcher, a new name to me, who also won in 1940, but the first few decades were dominated by two names, Gisela Kahn Gresser, who won nine titles between 1944 and 1969, and Mona May Karff, who won seven titles between 1938 and 1974. Other strong players who took part in that period included Mary Bain, winner in 1951, and Sonja Graf, Vera Menchik’s rival back in the 1930s, who took the title in 1964.

By today’s standards they weren’t amazingly strong players (Gresser was just below 2200 and Karff just below 2100 at their best in the 1950s), but as pioneers who achieved success in a male dominated field they deserve our respect and remembrance.

Here’s a game between Gresser and Karff. Click on any move for a pop-up window.

1959 champion Lisa Lane briefly caused a sensation in the chess world, appearing on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1961.

If you’ll excuse a digression into the history of Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club, I had a particular interest in this brief encounter.

Lane’s opponent, Henry Herbst (at least I presume it’s the same one) was a member of my club for several years in the middle to late 1970s, often playing on the adjacent board to me. From what I can piece together, he was born in Germany, moved to Canada, then to the USA, where he played this game, before moving to England and then back to Germany, where I believe he died a few years ago.

I was editing the club magazine at the time and Herbst submitted his game against Bobby Fischer for publication. When I checked it out in my book of Fischer’s collected games it was played by somebody with a different name, but with a similar rating and, as far as one can tell from two short games, a similar style of play.

Assuming he wouldn’t otherwise have claimed to have played a rather indifferent game, why was my friend Henry Herbst using two names? Both names appeared occasionally in other US tournaments at the time these games were played. I have my suspicions based on something I was told in confidence many years ago, but I couldn’t possibly repeat it here.

To return to the book, perhaps the leading figure in US Women’s chess between the mid 1970s and the mid 1980s was Diane Savereide, who took the title five times between 1975 and 1984.

She nominated this, against the author of this book (Rudolph was her maiden name) as her best game from the 1981 championship.

The overall standard of play gradually improved as the 20th century reached its end, but it wasn’t until the 1990s, with an influx of players from the former Soviet Union, that players with higher ratings started to compete on a regular basis.

This game won the brilliancy prize in 1997.

The dominant competitor in recent years has been Irina Krush, who took the title for the first time in 1998 and has won on seven further occasions between 2007 and 2020, leaving her only one behind Gisela Gresser: an impressive feat considering the strength of her opposition in recent years.

This game is from the 2015 championship.

Woven into the biographies and games are occasional stories of sexism and abuse, and, although they sometimes make uncomfortable reading, it’s entirely fitting that we can read them here. This is an issue the chess world has to deal with in order to make the game more attractive and inclusive.

I have a few minor gripes about the production. There are inconsistences, particularly in the presentation of the crosstables at the back of the book, which have been produced in the format in which they appeared in print. Perhaps it’s just a personal thing, but inconsistency really annoys me. I’d prefer them to be standardised in the same format. I also found the covers too flimsy, and, a point I’ve made before with softback books from this publisher, the presentation of the games, with very few diagrams, rather unattractive. I like to be able to follow games from the book without resorting to a board and pieces. I appreciate that the solutions I’d have preferred would not have been economically viable.

Nevertheless, this is a well-researched and thoughtfully compiled book which fills an important gap in the market. We need more books about women’s chess.

Whether you’re a female chess player, you teach female chess players, you have friends who are female chess players, or you have an interest in chess history and culture, this is a book you should read. Perhaps someone should also commission a book about the British Ladies/Women’s Chess Championship as well. That, too would be a very worthwhile project.

Richard James, Twickenham 13th September 2022

Book Details :

- Format: Softback

- Pages: 240

- Bibliographic Info: photos, diagrams, games, bibliography, indexes

- Copyright Date: 10th June 2022

- ISBN-10: 1476686939

- ISBN-13: 978-1476686936

- Imprint: McFarland & Company Inc.

Official web site of McFarland

Minor Pieces 43: Percival Guy Laugharne Fothergill

I received some exciting news last week. The Richmond Herald up to 1950, with extensive local chess coverage, is now available online. This means that I’ll be able to trace the history of chess in Richmond, Barnes, Kew and Sheen up to that date, which is not all that long before I came in.

But first, and with some help from the above source, a man who was strangely coy about his rather splendid full name.

Any chess problem aficionados at any point from the late 1880s to the late 1940s, which, you might think was the golden age of chess problems, would have been familiar with the initials PGLF above compositions, with a location of, perhaps, Twickenham, Staines or Isleworth.

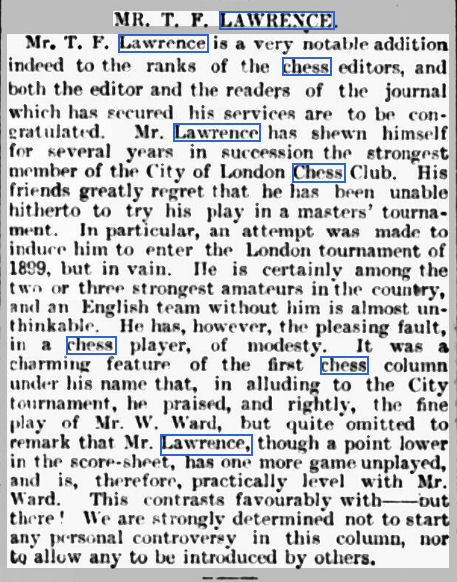

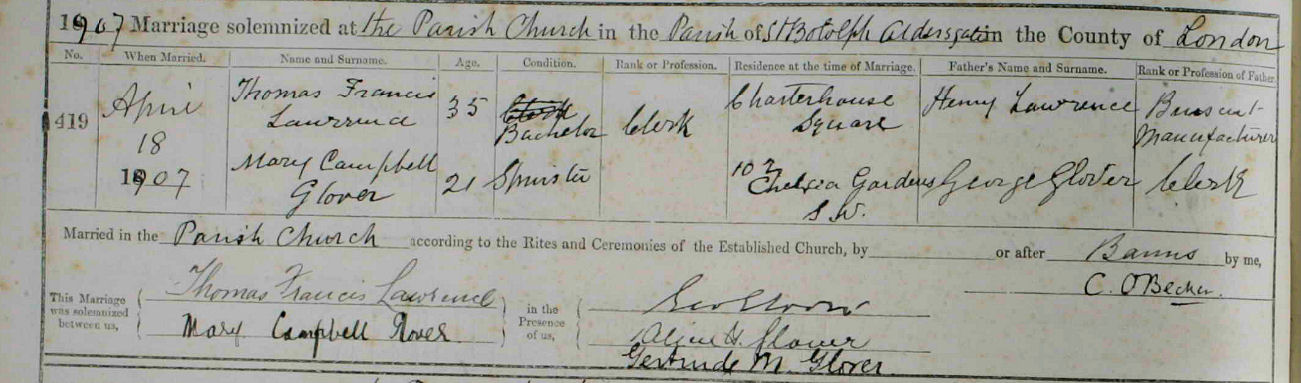

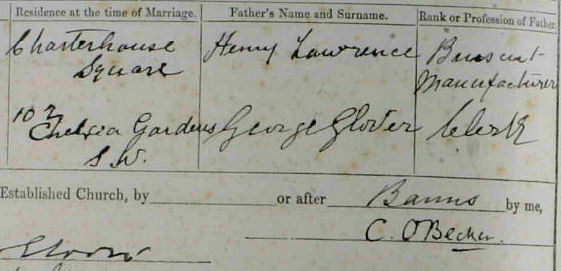

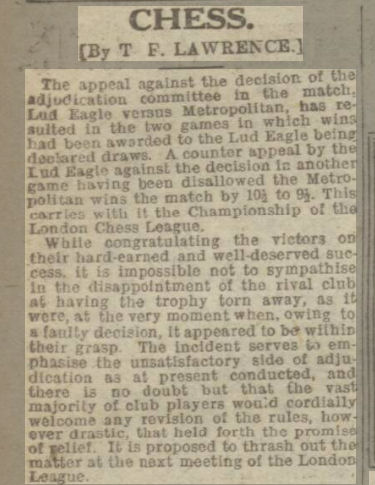

The name G Fothergill was often seen in connection with Richmond Chess Club, and with other clubs in the area. If you’ve been paying attention recently, you might remember him losing in a simul given by TF Lawrence.

In fact he was plain Guy Fothergill on electoral rolls for many years.

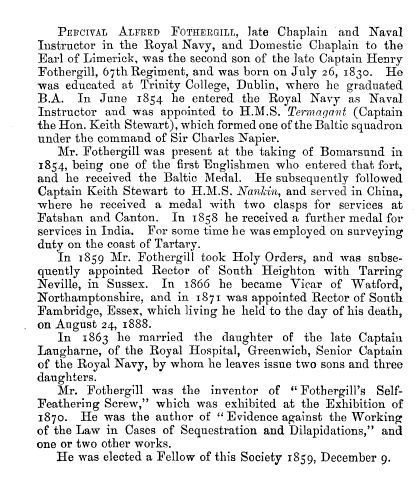

A good place to start is with his father, Percival Alfred Fothergill. Percy senior was an interesting and versatile chap. Naval officer, instructor, surveyor, engineer, inventor, astronomer, author, clergyman. You name it, he did it.

Here’s his obituary, from the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 049:4 (1889).

You might, understandably, be concerned about the self-feathering screw. Don’t worry: it was a propeller for sailing vessels. If you’re really interested in that sort of thing there’s a blog post here.

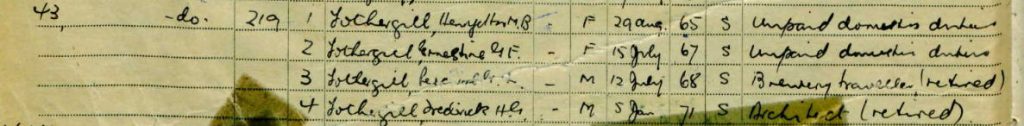

Percival and his wife Julia’s children, all equally impressively named, were Henryetta Mary Bertha (1865), Ernestine Gertrude Frances (1867), Percival Guy Laugharne (12 July 1868), Cornelia Julia Evelyn (1869), Frederick Henry Gaston (1871) and Arthur Yorke Marsh (1872), who died at the age of only six months. Frederick’s baptism record reorders his names: Gaston Frederick Henry.

The only births which were registered appear to be Henryetta and Frederick: at the time the family were moving round the country a lot and perhaps never got round to it.

At the time of the 1871 census Percival Alfred was the Vicar of Watford, Northamptonshire, north east of Daventry. You’ll know it from the Watford Gap service station on the M1. Their five young children, baby Fred yet to be named, were there along with a nurse and two domestic servants.

Ten years later, and the family seem to have split up. Percival was now the Rector of South Fambridge, Essex, on the River Crouch north of Southend, living in ‘part of the rectory’ along with Henryetta and Percival Junior. Julia and the other three surviving children were 20 miles away in Orsett, near Grays, on the Thames Estuary. One wonders what had happened.

There’s no immediate evidence of any other serious interest in chess in the family, but it was from his father that young Percival (perhaps we should call him by his preferred name, Guy, or by his initials) first discovered the Royal Game. By 1886 the teenage Fothergill was already having his problems published.

Here’s a (rather crude) early example of a mate in 2. You’ll find the solutions to all the problems at the end of the article.

Problem 1

#2 (The Field 11 Sep 1886)

His problems were soon becoming more sophisticated and even winning prizes, like this mate in 3.

Problem 2

#3 (2nd Prize Sheffield Independent 1888)

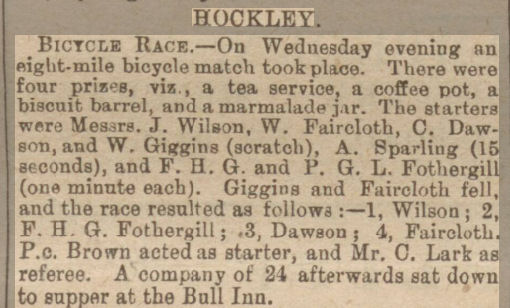

Problem composing wasn’t the only competition he took part in. Here, he and his brother took part in a bicycle race, with Fred winning a coffee pot for finishing second.

Sadly, his father died the same year in Little Burstead, south of Billaricy, the village where he was born. By the time of the 1891 census he’d left home, was boarding in (not yet Royal) Wootton Bassett and working as a Brewer’s Pupil. Julia had retired to Milford, on the Hampshire coast, where she was living with Henryetta, Cordelia and Gaston, as Frederick now preferred to me known. Ernestine was in Acton, working as a Governess.

PGLF won 1st prize with this 1894 mate in 2.

Problem 3

#2 (1st Prize Hackney Mercury 1894)

Round about 1895 the family moved to St Margarets Road, on the border of Twickenham and Isleworth. I’m not sure exactly where, but the 1901 census implies it was somewhere close to the Ailsa Tavern.

As expected, PGLF featured in FR Gittins’ The Chess Bouquet in 1897.

His list of successes is not large, nor are they phenomenal, but his work has merited and received a fair reward…

We also learn that

MR FOTHERGILL is a great lover of all manly games – cricket, football, lawn tennis, etc., a sound mind in a sound body being one of his favourite maxims.

And here he is, with a splendid moustache to match his splendid name.

It’s at this time that Guy decided to expand his interest in chess, and, while still composing (as PGLF), his name (G Fothergill) started to appear in chess matches.

Here’s a 1899 match between Richmond and Thames Valley, with Mr G Fothergill playing on bottom board for the home team.

It’s clear there’s a problem with this. Fox, Britten, Ryan and Coward must have been on 3-6, not 4-7, with Lanchester and another player on 7 and 8. Regular Minor Piece readers will recognise several old friends in this match, and there are one or two others you’ll meet in later articles.

The 1901 census found Julia, Henryetta, Cordelia and Gaston, who was now known as Henry, in residence in St Margarets, none of them appearing to have jobs. Ernestine, however, was occupied as a Lady’s Companion in Hersham. I haven’t managed to locate Guy in 1901: perhaps he was abroad on holiday. At any rate, he was still telling everyone he lived in Twickenham.

From the same year, here’s another prize-winning problem.

Problem 4

#2 (3rd Prize Brighton Society 1901)

This miniature 3-mover demonstrates a popular theme. Even if you’ve never solved a mate in 3 before, give it a try!

Problem 5

#3 (Schachminiaturen 1903)

At about this time Guy Fothergill suffered two bereavements: his mother Julia died in 1905, and his sister Cornelia followed her a year later. Probate records tell us they were both living at Shortwood House, Staines: Shortwood Common is right by the Crooked Billet roundabout heading towards Ashford. Julia’s probate was granted to Henryetta and Guy, and Cornelia’s probate just to Guy. Although she was living in Staines, she died at 89 St Margarets Road, Twickenham. The numbering may be different now, and it’s a long road, but 89, currently a private healthcare clinic, is currently just round the corner from Turner’s House and a short walk from the ETNA Community Centre, where Richmond Junior Club met for many years. So it may well be that the family owned two properties at the time. It’s not at all clear to me at the moment whether or not this is the same address they were at in 1901.

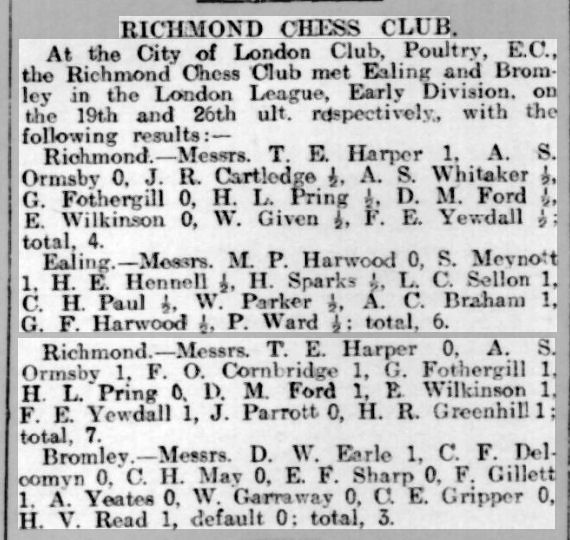

As the Edwardian era wore on, there were subtle changes in the balance of power between the Richmond and Thames Valley Clubs. At the start of the decade Thames Valley had been stronger than their younger neighbours, but a few years later Richmond were displaying more ambition (and, it appears, better organisation than a few years earlier), entering the Early Division of the London League and attracting stronger players. (I presume the Early Division played matches earlier in the evening than, well, perhaps the Late Division?)

You’ll also notice that by now Guy had been promoted from bottom board, and AGM reports for the period show that he was also doing well in internal competitions,

Now approaching his 40th birthday, life for PGLF proceeded uneventfully as he continued to play chess and compose problems.

The 1911 census, though, finds the Fothergill siblings split up, living neither in Staines nor in Twickenham. Guy, ‘of private means’, was boarding at a Temperance Hotel in Maidenhead (what happened to his brewing career, then), while Henryetta and Ernestine were both staying with a restaurant owner in Reading, who may well also have had rooms for boarders. There’s no sign of their younger brother.

By 1914, PGFL’s problems are now being submitted from Staines. Was he living in Shortwood House? Possibly: at present that information isn’t available. He also had the opportunity to join a new chess club.

You’ll notice that there were two ladies in the team facing Kingston: Mrs Cousins and Miss Hume. We’ll return to them in a future Minor Piece.

He maintained his membership of Richmond Chess Club as well, taking part in internal competitions and serving on the committee.

In 1918 PGLF was enrolled as a founding member of the British Chess Problem Society.

The country was now returning to normal after the First World War, and the 1919 electoral roll tells us that Henryetta was still at Shortwood House, London Road, Staines. By 1921 she’d been joined by ‘Fred’ (neither Gaston nor Henry) and Percival (not Guy).

Neither brother was anywhere to be found in the 1921 census (at least I haven’t been able to find them yet). Their two sisters, both still unmarried in their mid 50s, were lodging in Goldhawk Road, Hammersmith, near the junction with King Street – even though the electoral roll had Henryetta in Staines. The census enumerator found the house unoccupied.

A short walk from Goldhawk Road along King Street towards Hammersmith Broadway would have taken them past Latymer Upper School, and then round the corner to what is now the London Mind Sports Centre.

If they’d only stayed in Staines another year or two they could have strolled past the Crooked Billet towards the town centre and dined at 8 London Road, the Warwick Castle, where the Misses Ada and Louisa Padbury were combining running a restaurant with bringing up their irresponsible sister Florence’s illegitimate daughter Betty. But that’s another story for another time, which also involves Edward Guthlac Sergeant and Fothergill’s Richmond teammate Cecil Frank Cornwall.

At some point, perhaps just after, WW1, the Ashford and District Chess Club was founded. Guy, along with Mrs Cousins, joined up, he soon found himself playing successfully on top board against Richmond. It may well have been on his initiative that matches between the two clubs came about. Today there’s a Staines Chess Club, but not an Ashford Chess Club.

In 1922 Henryetta must have sold Shortwood House and brought a property in Isleworth, 43 Thornbury Road.

I’m not sure that the house still exists. 41 is a large corner property, but the adjacent plot seems empty according to Google Maps.

She’s the only occupant on the electoral roll for several years, but by 1929, Guy (not Percival this time) is also there, although Henryetta is declared to be the owner. I presume he’d been living there all along, though, as he was giving Isleworth as his residence when submitting problems for publication.

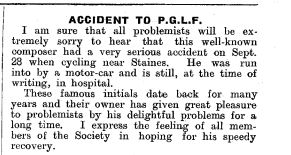

He still visited his old haunts in Staines, but in 1936 was seriously injured in a cycling accident. Fortunately, he made a full recovery.

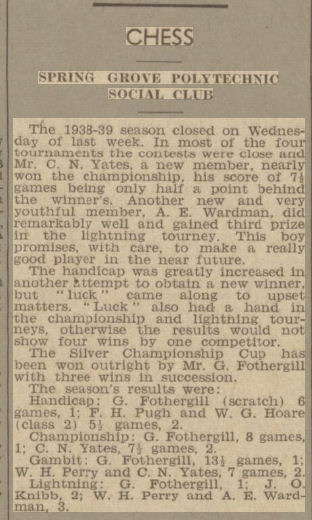

By the late 1930s, if not earlier, he’d found a very local chess club to join, just round the corner from his residence.

He was now in his seventies, but still made a clean sweep of all the trophies. The opposition may not have been the most demanding, but you can do no more than beat what they put in front of you.

Here they all are in the 1939 Register, all living in Thornbury Avenue (perhaps they’d all been there all along), all single, and aged between 65 and 71. Percival is a Brewery Traveller (retired), but I’m not sure he did much Brewery Travelling, while Frederick is an Architect (retired), but again I’m not sure he designed very many buildings. I can’t find any record of him in that sphere.

PGLF was still composing, though not quite as prolifically as before. This 3-mover from the latter part of his career demonstrates the theme of symmetry.

Problem 6

#3 (The Problemist March 1944)

This, then, was a fairly wealthy family, with enough money not to need much in the way of employment, and seemingly with no interest in matrimony. This gave them time to pursue their hobbies, and, in PGLF’s case, that hobby was chess. It’s spookily like James Money Kyrle Lupton‘s family, isn’t it?

Ernestine was the first to go, dying in 1945 and leaving £6711 (round about £200000 to £250000 today), probate being granted to Frederick.

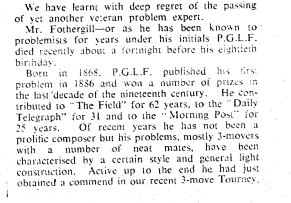

Percival/Guy/PGLF died on 29 June 1948, leaving £4486 10s 4d, again probate being granted to Frederick. He was composing to the end: almost two years after his death, his problems were still being published.

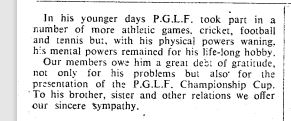

Here’s his obituary from The Problemist, rather belatedly in January 1949.

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

Unfortunately the accompanying photograph didn’t reproduce well.

Unfortunately, also, the recent commendation turned out to be cooked, so I won’t demonstrate it here.

Henryetta, address given as 32 Stamford Brook Road, just round the corner from where she was in 1921, died in 1954, leaving £5528 8s 10d, yet again probate granted to Frederick.

Frederick, or Gaston, or Henry, or whatever, lived on until 31 December 1962, living at 45 Woodlands Grove Isleworth, not far from Thornbury Road, and leaving £15307 17s.

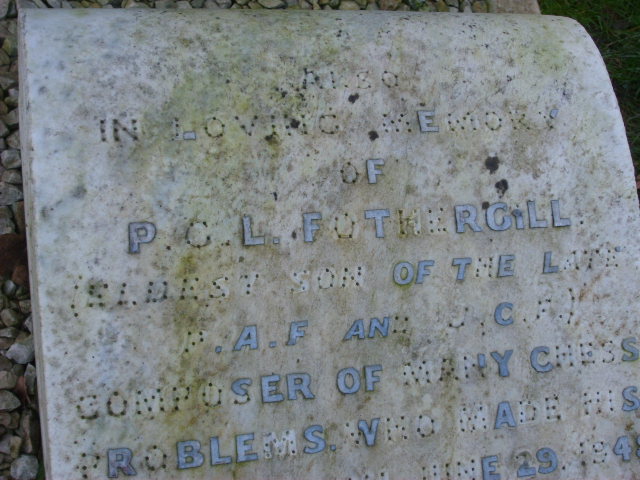

Four of the siblings (not, for some reason, Ernestine) share a gravestone in the family’s home village of Little Burstead, Essex. Percival’s inscription reads:

| Also in loving memory of P.G.L. FOTHERGILL [eldest son of the late P.A.F. and J.C.F.], composer of many chess problems who made his last move on June 29 1948 on the eve of his 80th year.

“Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace whose mind is stayed on Thee because he trusted in Thee.” Isaiah XXVI. 3 |

Yes, indeed, a composer of many chess problems. Mostly direct mates, latterly mostly mates in 3, but with a few selfmates (where White compels an unwilling Black to deliver checkmate). Mostly lightweights rather than heavy award-winners, but none the worse for that. He was, similarly, a good chess player – higher club standard – but not a great one. I have yet to find the scores of any of his games. Percival Guy Laugharne Fothergill was a man who, through his problems, must have brought a lot of pleasure to a lot of people. Perhaps you’ll derive some pleasure from attempting to solve the problems in this article. A minor contributor to a minor art form, I suppose, but still a life well lived and well worth remembering.

If you’d like to see more of his (or anyone else’s) problems I recommend:

https://www.yacpdb.org/

http://www.bstephen.me.uk/meson/meson.pl?opt=top

https://www.theproblemist.org/mags.pl?type=tp

Acknowledgements and sources:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

findagrave.com

Wikipedia

Google Maps

The Problemist

MESON chess problem database

YACPDB (Yet Another Chess Problem DataBase)

Other sources referenced within the article

Problem solutions.

Problem 1:

1. Qd8! and all four Black moves allow knight mates. There are duals in three of the four variations, which wouldn’t be acceptable today.

Problem 2:

1. Ba3! when the star line is 1… Kxc4 2. Qb5+! Kxb5 3. Nd6#. Also 1… Kxe4 2. Qe2+, 1… Ke6 2. Qb6+, 1… d3 2. Qd5+ and 1… g2 2. Qb5+

Problem 3:

1. Re8! A waiter, very popular at the time. The move creates no threat, but every Black move creates a weakness allowing White to mate next move. You can work them all out for yourself!

Problem 4:

1. Bh2! Another waiter: again there’s no threat but every possible Black reply allows immediate checkmate. There are quite a lot for you to find!

Problem 5:

1. Nc3! Kb4 2. Qc4+!, or 1… Kb6 2. Qe7!, or 1… Kd6 2. Ne4+!, or 1… Kd4 2. Ne4! This demonstrates the Star Flight theme: Black’s four possible king moves, SW, NW, NE and SE, make the shape of a star.

Problem 6:

There’s some set play: if it was Black’s move 1… c2 would be met by 2. Qa5. There are also two tries: 1. Rg7? d5+! and 1. Rc7 f5+!

So the solution is 1. Qe3! when it’s not difficult for you to work out the variations after Black’s four possible replies.

Chess for Schools (Crown House Publishing)

If you know me at all you’ll be aware that I’ve been involved with junior chess since 1972. If you’ve spoken to me on the subject you’ll also be aware that my views on why, how, where, when, to whom and by whom chess should be taught are very different from those propounded by most junior chess teachers and organisers in the UK.

In particular, I have doubts about the value of much of what currently happens in primary school chess, which has always appeared to me to provide short-term fun at the expense of genuine long-term benefit.

I was commissioned by education publishers Crown House to write a book for schoolteachers putting forward my suggestions as to how schools might take a different approach to chess.

My views in brief (and in general) about how junior chess in the UK should be run:

- Promote simple strategy games (minichess) in primary schools – this is discussed in my book

- Establish a network of local community based junior chess clubs with links to primary schools

- Establish a network of regional professionally run junior clubs for more ambitious children

- Promote chess in secondary schools, especially those in the public sector, and establish links with local chess clubs

The book has now been published: you can find out more on the publisher’s website here.

Here’s what GM Peter Wells has to say about the book:

When I began to read Chess for Schools, I was aware of two salient facts: that Richard James has tremendous experience teaching chess to children – in a classroom setting and as founder of the famously successful Richmond Junior Chess Club; and that he has been a consistent critic of much current chess teaching practice – particularly in primary schools, where he believes the teaching of chess is frequently pitched at an unrealistic level in relation to the cognitive development of the pupils. I was consequently well-prepared for a text that might ruffle some feathers.

I was not disappointed. There are undeniably passages in the book which will make uncomfortable reading for some chess teachers and parents. Yet far from the feeling that Richard James is gratuitously courting controversy, I came to regard his unwillingness to pull punches with many in his target audience as a mark of the book’s uncommon integrity. His views are the product not only of great experience but also of a persistent quest to improve the outcomes for his pupils, both those with lofty chess ambitions and those who will enjoy a variety of relationships with the game. He has read widely and thought deeply, and the result is a coherent, very readable and well-structured argument which he makes with obvious passion.

Here’s former Head Teacher Tim Bartlett, taking a teacher’s perspective:

This brilliant book is a three-layered cake. It is so well structured that you do not need to read it from end to end and you do not need ever to have touched a chess piece to find it worthwhile. The one key message for teachers is: if you can teach children, you can teach chess. That is, just as there comes a point when pupils will benefit from a specialist geographer, swimming instructor or mathematician, so it is with chess. The first layer sets the scene. It is easy to read, covers the history of chess and its place in education, what chess is – and, crucially, what it is not. The second layer is an impressively brief and comprehensive survey of the place of chess in the curriculum, and it’s not where you think it might be. This layer will make you think about curriculum development in broad terms as well as in relation to chess. It will make you think about the role of parents and parenting in children’s schooling. The book is properly, academically, referenced. The final layer is a manual of chess resources. The book stands alone as a good read without this section. My main revelation was just how many different games you can play with a chess set – it’s as if I had only ever learnt to play snap with a pack of cards.

If you’re sympathetic towards my views and would like to speak further, do feel free to get in touch. I’m always happy to discuss my ideas with anyone involved in any aspect of junior chess.

The Magnus Method: The Singular Skills of the World’s Strongest Chess Player Uncovered and Explained

Here is the publishers blurb from the rear cover :

“What is it that makes Magnus Carlsen the strongest chess player in the world? Why do Carlsen’s opponents, the best players around, fail to see his moves coming? Moves that, when you replay his games, look natural and self-evident?

Emmanuel Neiman has been studying Carlsen’s games and style of play for many years. His findings will surprise, delight and educate every player, regardless of their level. He explains a key element in the World Champion’s play: instead of the absolute’ best move he often plays the move that is likely to give him the better chances. Carlsen’s singular ability to win positions that are equal or only very slightly favourable comes down to this: he doesn’t let his opponents get what they hope for while offering them the maximum amount of chances to go wrong. In areas such as pawn play, piece play, exchanges as a positional weapon and breaking the rules in endgames, Neiman shows that Magnus Carlsen has brought a new understanding to the game.

Neiman also looks at Carlsen’s key qualities that are not directly related to technique. Such as his unparalleled fighting spirit and his ability to objectively evaluate any kind of position and situation. Carlsen is extremely widely read and knows basically everything about chess. What’s more, as the most versatile player in the history of the game he is totally unpredictable. The Magnus Method presents a complete analysis of the skills that make the difference. With lots of surprising and instructive examples and quizzes. Examining Carlsen’s abilities together with Emmanuel Neiman is a delightful way to unlock you own potential.”

About the author :

Emmanuel Neiman is a FIDE Master who teaches chess in his home country France. He is the (co-) author of Invisible Chess Moves and Tune Your Chess Tactics Antenna, highly successful books on tactics and training.

The Chapters are as follows:

Explanation of symbols

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1) Style: from Karpov to Tal?

Chapter 2) The opening revolution

Chapter 3) Attack: inviting everyone to the party

Chapter 4) Defence: the preventive counter-attack

Chapter 5) Tactics: ‘les petites combinaisons’

Chapter 6) Exchanges: Carlsen’s main positional weapon

Chapter 7) Calculation: keeping a clear mind

Chapter 8) Planning: when knowledge brings vision

Chapter 9) Pawns: perfect technique and new tips

Chapter 10) Pieces: the art of going backwards

Chapter 11) Endings: breaking the principles

Chapter 12) How to win against Magnus Carlsen: the hidden defects?

Chapter 13) Games and solutions

Index of names

Bibliography

Emmanuel Neiman has produced a fascinating book in which he tries to answer the question; what makes Magnus Carlsen unique and sets him apart from his peers? Magnus is currently the 5 time world champion and been the no.1 position in the FIDE World rankings since July 2011. In addition to this remarkable feat Magnus has also been the World Rapid Chess Champion (three times) and the World Blitz Champion (five times). This is even more remarkable when you consider that Magnus is still only 31. Since the book was published in 2021 Magnus has announced that he will not be defending his title and will effectively step down as world champion in 2023. As well as his achievements over the board Magnus co founded the company Play Magnus AS in 2013 and in Aug 2022 the company accepted an offer from Chess.com that will see the two companies merge.

A lot has been written about Magnus Carlsen over the years but one of the most interesting articles I found was written by Jonathan Rowson in 2013 in which he described Magnus as a ‘nettlesome’ player. “we needed the word ‘nettlesomeness’ to capture the quintessence of his strength, which lies in his capacity to induce errors by relentlessly playing moves that are not only good, but bothersome.” (https://en.chessbase.com/post/carlsen-the-nettlesome-world-champion Magnus is a very pragmatic player, who has the ability to play accurate moves that maximise the chances for inaccuracy by his opponents rather than always looking for the ‘best’ move. Magnus is also an extremely well-rounded chess player. In terms of dynamic attacking play, Kasparov was probably better than him. In terms of positional play people will argue that Karpov and Kramnik at their best could give Magnus a run for his money. However, no player in chess history can play both tactical, strategic and technical positions as well as Magnus. He is also one of the toughest defenders out there. He does occasionally get bad positions but when he does, he digs in and defends like his life depends on it. His opponent has to play with razor-sharp precision to even think about winning. Finally, Gary Kasparov in an interview once described Magnus as a lethal combination of both Fischer and Karpov https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Np1zODg5cqc.

In writing this book the author sets out to answer two questions; firstly, what does Magnus bring to the game and secondly what specific tools does he use? When you play though his games they can look deceptively simple. At some point his opponent (often one of the best players in the world) will blunder, often after conducting a long and difficult defence in a seemingly level endgame.

The introduction spans 21 pages and could have been a stand-alone chapter covers two aspects of Carlen’s play, his technique and the characteristics of his play that are not directly related to technique. The technique covers how Magnus is able to win equal or slightly advantageous positions, even against the strongest players in the world. Carlsen will try and keep the position alive at all costs and avoid getting to a position where his opponent knows what to do. Carlsen will constantly look for ways to change the position in both the middlegame and the endgame. So that when his opponent has solved one problem he will be faced with a further set of problems.

Moving onto Carlsen’s strong points the author examines the following attributes:

- Evaluation – constantly trying to get an objective assessment of a position before making any decisions or making a plan.

- Chess Knowledge – practically knows everything there is to know about the game.

- Versatility – he can play virtually any opening and any type of game.

- Fighting Spirit – sets out to win every game he plays.

- Pragmatism and Perfectionism – Carlsen is a pragmatist rather than a purist.

- Intelligence/psychology – Carlsen was a gifted child and owes very little to coaches or outside help.

Chapter 1 covers Magnus’s style of play and how that has changed over time. Starting out as a tactician then becoming a more technical player then evolving into the universal player that he is today. This has enabled Magus to be successful in all formats of the game. Chapter 2 describes the changes that have taken place in opening preparation. Previously elite players would prepare long concrete lines and spend a considerable time researching opening novelties. Many openings were not played by the top players as they weren’t considered to be strong enough. Carlsens approach is radically different and he will literally will play anything and everything. This has minimised the importance of the opening and placed more emphisis on middlegame and endgame play.

Chapters 3 -10 These 10 chapters each cover a particular characteristic of Carlsen’s play and begin with a short introduction followed by a number of exercises for the reader to solve. The solutions are found in the final chapter of the book. (Games and Solutions) This consists of 248 annotated games or positions. The structure of this book is different from other similar books where the reader is asked to solve a position and find the correct move for one side. Here the diagrams at the end of each chapter refer to specific games and specific diagrams within the game. However I did have a problem with this approach as I feel that there were too many problems to solve from specific games and in many cases several diagrams were included where there are only few moves between the diagrams. In several cases like this I was able to work out the solution to a problem by referring to the next diagram and deducing how to get to the next position. Also, it is not clear whether the reader is being asked to find a single move or to calculate a number of variations. I would have liked to have known in advance how difficult each problem is to solve. This does detract from the book but it making it a good book rather than an excellent one.

Clearly a lot of research has gone into producing this book and organising the material therein. Virtually all of the games in this book were played against the world’s elite players with the most recent games played in 2021. Some of these games are from online events even including a couple of games from ‘Banter Blitz’ events. There are also a few of his junior games as well. The games are well annotated with a nice balance between explanations and analysis. This book can be read either as a collection of puzzles to solve or the reader can skip the puzzles and just enjoy playing through the games.

Overall the author succeeded in answering the two questions that he posed at the beginning of the book specifically what Magnus Carlsen brings to the game and what is his approach. The book does not cover how Magnus was able to adapt his play and be so successful in the online tournaments that were played throughout 2020 & 2021. I presume that this was because the book was written in early 2021 and perhaps this will be addressed in a future edition.

Addendum, the day after I finished completed this review I saw an article on the Chessbase website that Magnus Carlsen had just recorded a podcast with Lex Fridman (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ZO28NtkwwQ ) This is a 2.5 hour conversation covering a wide range of chess (and non-chess) related topics. Lex has previously interviewed Gary Kasparov (see link above) and more recently Demis Hassabis ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gfr50f6ZBvo ) CEO and co-founder of DeepMind.

Tony Williams, Newport, Isle of Wight, 30th August 2022

Book Details :

- Paperback : 320 pages

- Publisher:New In chess (9 Oct. 2021)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:9056919687

- ISBN-13:978-9056919689

- Product Dimensions: 17.17 x 2.11 x 23.67 cm

Official web site of Everyman Chess

Blind Faith

From the publisher:

“Chris Ross has come a long way from the back streets of Middlesbrough to a senior administrative role at Sheffield Hallam University, helping the education of those with a wide range of disabilities. A former teacher, Chris’s natural ability to educate has developed many of his colleagues in UK chess clubs – and not least, fellow members of the Braille Chess Association.

Join Britain’s strongest ever blind player and 2015 IBCA Olympiad silver-medallist Chris Ross on a journey through 80 of his most memorable games. Many years ago Chris elected to follow Botvinnik’s advice by writing deep analysis to his games: initially to better understand his own style, but later because his highly detailed annotations are also highly instructive for weaker players.

This collection charts his journey from turbulent days as a strong club player in 2006 to a more polished and rounded style by 2020. From smooth, positional wins, to bumpy, sharp encounters, we watch and learn with Chris as he develops into a 2250-strength player. The reader will pick up many handy tips to improve their own game: opening repertoire, middlegame and endgames strategies, and – crucially – appreciating how to plan.”

I’ve long thought that, while looking at top level games can be inspirational, you can learn much more either from studying games played at your level and looking at typical mistakes, or from studying games played by someone rated about 200-300 points above you and learning to do what they do.

Chris Ross is about 200-300 points stronger than me, so, at least in rating terms, I might be seen as the ideal reader for this book.

If I look at a Magnus Carlsen game I’d think “Wow! I could never conceive how I could play like that!”, but, looking at a Chris Ross game I might think “Yes! I could learn to play like that by studying his book!”.

I’ve always seen myself, by temperament rather than ability, as a positional rather than a tactical player, but when I played someone of about Chris’s strength I’d often find my opponent would latch onto a, to me, imperceptible weakness, win a pawn and grind me down in the ending. If I ever played Chris, I’m sure the same thing would happen.

Chris is a positional player as well, but, unlike me, he really knows what he’s doing.

Having been coached for many years by GM Neil McDonald has clearly helped.

Here’s Neil in the Foreword:

Many years ago Chris Ross made the excellent decision to follow Botvinnik’s advice by writing deep analysis to his games, and then sending it to his colleagues and friends in the chess world. Many players including myself regularly receive emails with his deep and interesting comments to his games.

and

You can see the outcome of decades of exhaustive and objective analysis in this book. Although Chris has never been a full-time chess player, having pursued a successful career in academia, his approach has always been professional. He has developed an impressive opening repertoire, as well as worked on his endgames and middlegame planning. I hope the reader enjoys this fine collection, and is inspired to follow Chris’s example in studying their own games.

Chris provides the reader with 80 games played between 2006 and 2020, mostly, but not exclusively, games he won.

In his introduction he explains his method of annotating games.

I do not display lengthy variations of computer analysis. Indeed I deliberately avoid many annotated games that possess such streams of text. I find it baffling and unhelpful. So, I do not adopt that style in my own writings. My analysis is instead based on my way of thinking, how I am attempting to obtain something and the such like. Naturally, that may inevitably mean that the annotated game may have flaws in it, due to computer analysis finding a better way to play. This does not interest me either. My intention is to show how I’ve focussed myself mentally and how, through that elaborate dance of non-visualisation and figuring out a way to play the game of chess, I’ve gradually but inevitably improved.

A very unusual approach to annotation, then, and something very different from anything I’ve seen in any other recent book. Another, perhaps, unique, feature of Chris’s annotations is that he provides the opening references at the end of each game rather than incorporating them at the appropriate points. You might think this is an excellent idea, not interrupting the flow of the text, or you might find it rather frustrating. I guess you could argue either way.

One of the things that immediately struck me when reading this book was that, on several occasions, he’d present a diagram of a position which looked to me about equal and claim that one player had a winning advantage. Well, perhaps. We’ll see.

Here’s a particularly interesting example which will give you a flavour of the style of Chris’s annotations, and, perhaps its weaknesses as well as its strengths.

This is from Peter Mercs – Chris Ross (4NCL 2014), with Black about to play his 15th move.

Some extracts from Chris’s annotations:

Ultimately, Black is positionally winning, despite the aggressive potential of the white attack. To fully appreciate the position in its entirety, the actual manoeuvrability of all the forces have to be considered and their fluidity. What is White immediately threatening, and is Black able to react immediately, or slowly against such a threat?

A position deep with potential, but rich in understanding. Consider carefully and read on!

15… Nb8!

A remarkable retreat, which resolves all of Black’s difficulties and puts into place all his positional objectives. In doing so, Black also defends against all of White’s intentions. After this incredibly calm, slow move, White has no real play at all.

Now we have another five paragraphs of explanations and a few variations before:

16. g4

With very little left for White in the position, he pins all of his hopes on a last minute king-side hack, which is doomed to fail from the outset, due to the superiority of the black pieces.

Now, another paragraph and a half of comments.

16… d5

A flank attack is suitably countered by a central attack. Due to the superior positioning of the black forces, the tactics work themselves out.

17. g5 dxe4