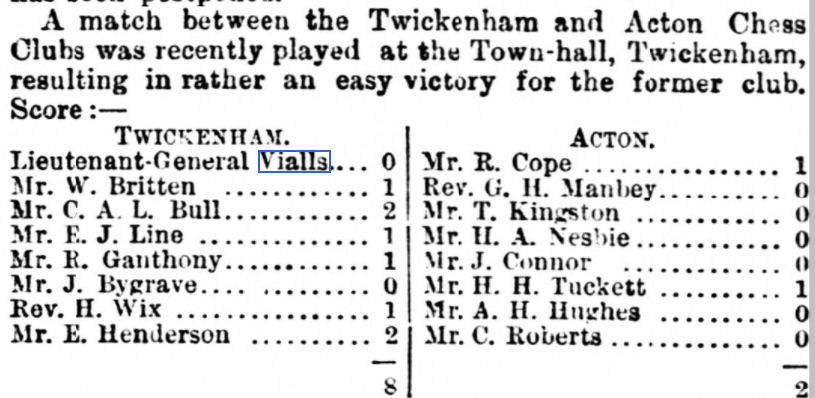

Last time we left Twickenham’s finest chess problemist, Cecil Alfred Lucas Bull, as he was about to emigrate to Durban in 1892.

Unfortunately, South African online records, both births, marriages and deaths, and newspaper archives, are few and far between, but we are able to provide a fairly comprehensive record of his chess career in the southern hemisphere, both as a player and as a problemist.

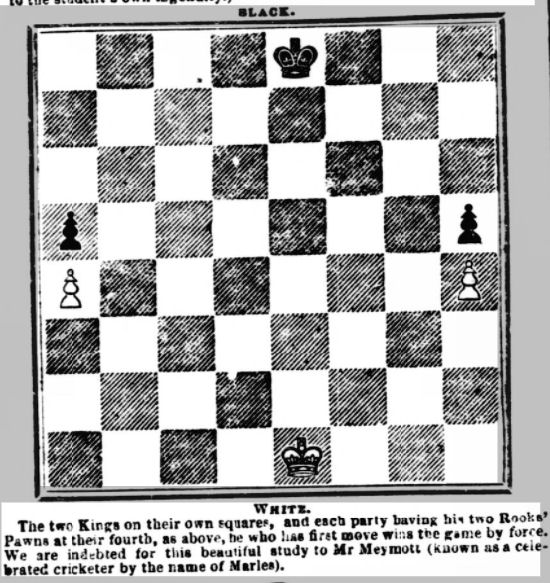

This problem, submitted to a London newspaper, dates from soon after his arrival in Durban.

Problem 1. Mate in 3: 1st prize winner Hackney Mercury 1894

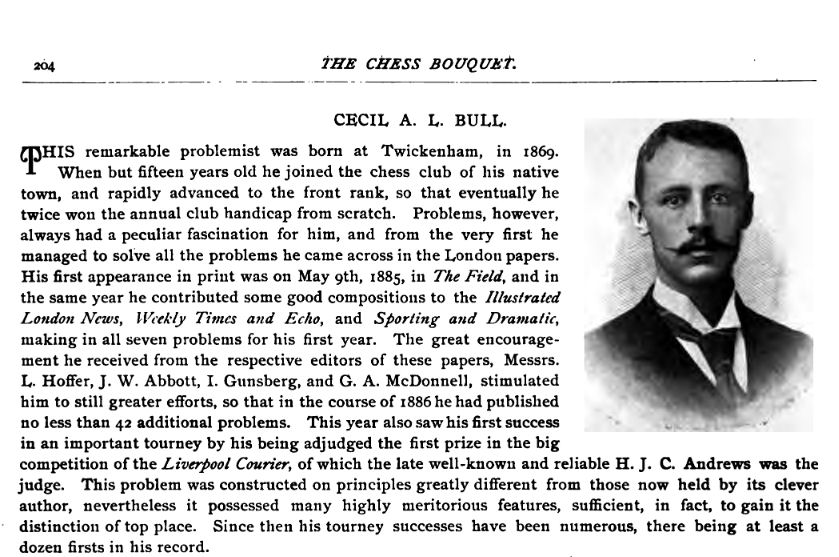

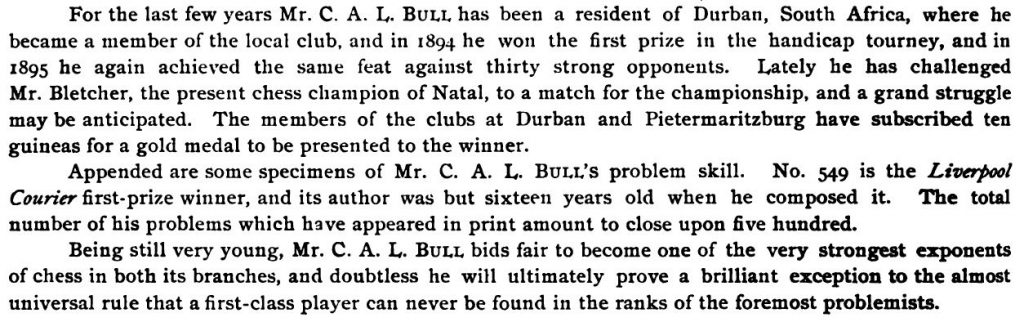

And here, continuing where we left off last time, is FR Gittins again.

We know from some useful information on the Durban Chess Club website that he was one of the founders of the club and was Durban champion five times, in 1901, 1903, 1904, 1906 and 1911

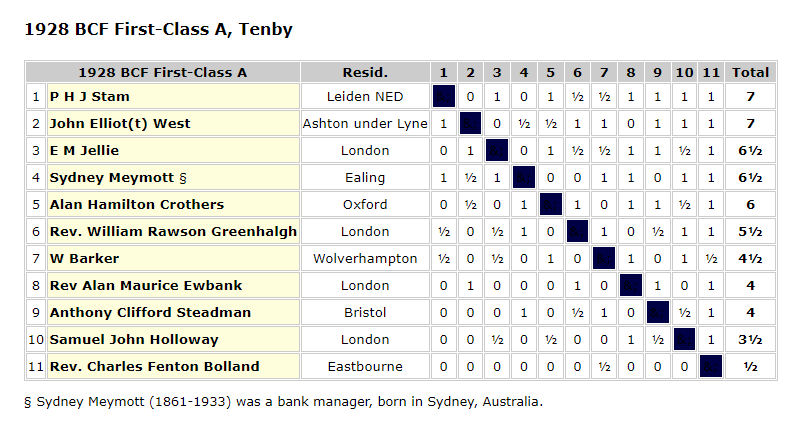

Lucas Bull was one of the founders of the Durban Chess Club in 1893 and the first person to win the Durban championship on five occasions, running out the winner in 1901, 1903, 1904, 1906 and 1911. He also participated in the South African championships on three occasions, finishing 9th in 1897, 7th in 1899, and 2nd on his final appearance in 1906.

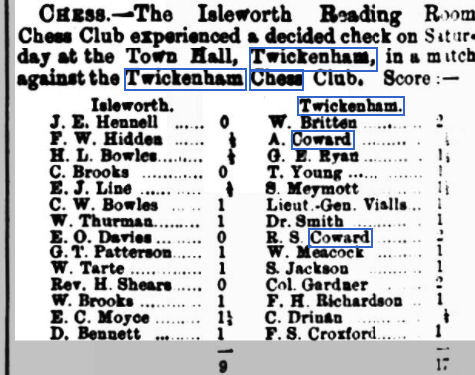

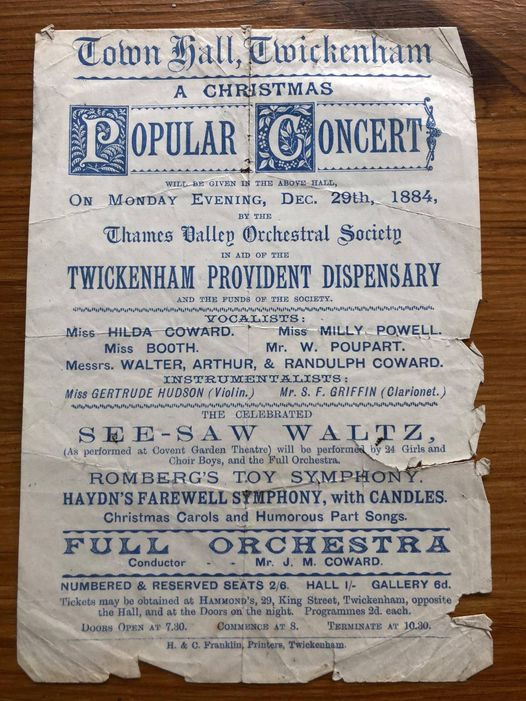

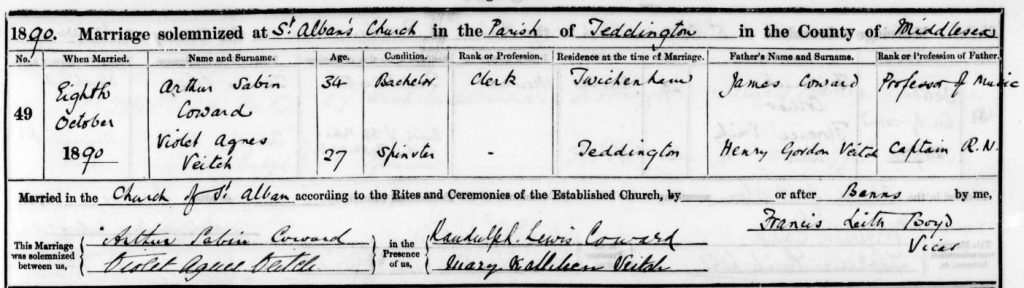

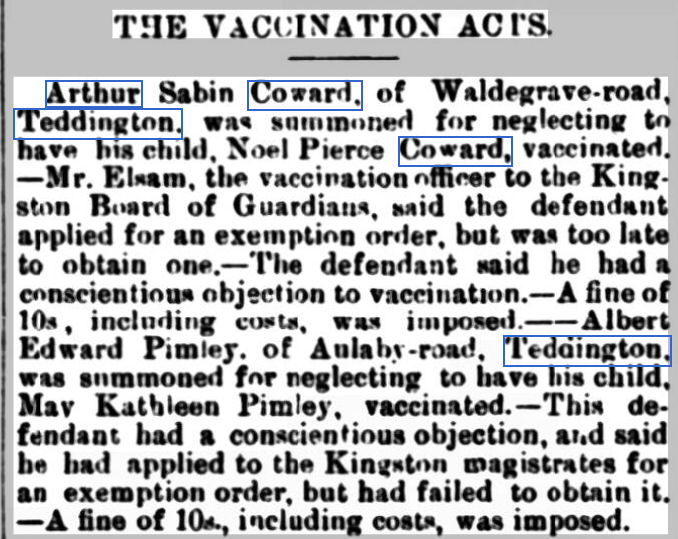

Lucas Bull was born in Twickenham (part of London) in 1869, and came from a very large family, consisting of five sons (he was the third son) and four daughters. His father, Thomas Bull, was a surveyor and auctioneer, and must have had a profitable business, as the Bull family employed four servants at the time (source: 1881 census).

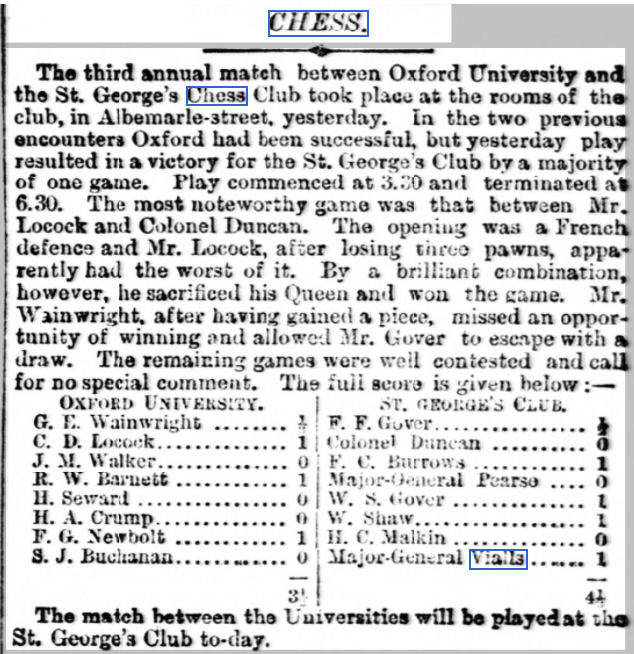

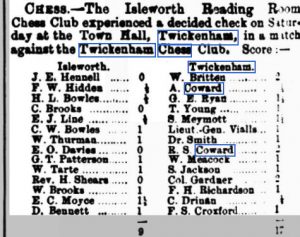

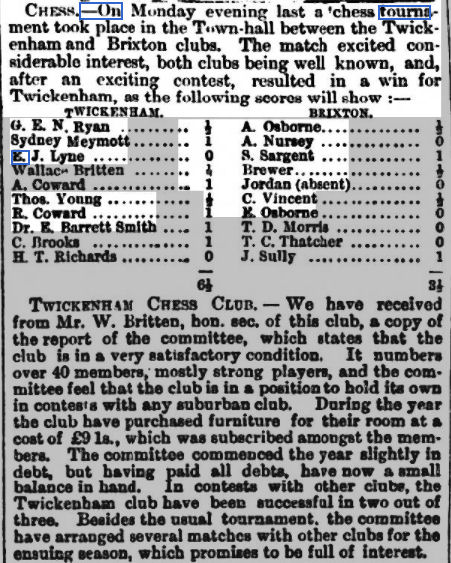

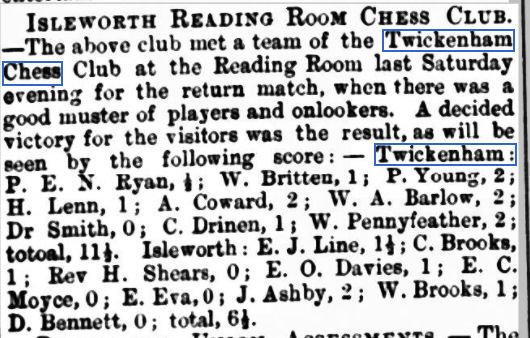

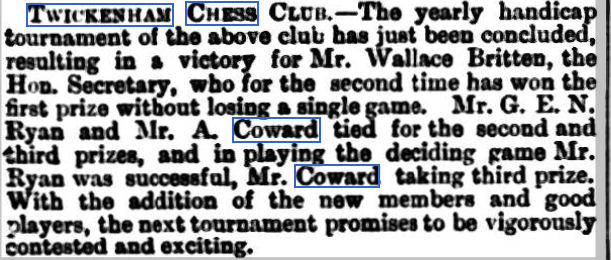

Bull arrived in Durban in 1892 and apparently chose South Africa, rather than the United States, as they don’t play cricket in the USA! He was already the champion of the Twickenham Chess Club, and was starting to get an international reputation as a problemist. From the date of his arrival, up until the time that he discontinued serious over the board play in 1907, he was almost certainly the strongest player in Natal.

Source: Durban Chess Club website http://www.durbanchessclub.co.za/bull.html

Further information about his appearances in the South African Championships (1897: Cape Town, 1899 Durban, 1906 Cape Town) can be found on Rod Edwards’ indispensable EdoChess site.

Two games from the 1899 tournament, played in the shadow of the 2nd Boer War, are extant. Click on any move and a pop-up board will magically appear, enabling you to play through the games.

The Bock game. which was awarded a brilliancy prize, was published, for example, in the Newcastle Courant (17 March 1900). The van Breda game comes, via South Africa chess historian Len Reitstein, from the Durban Chess Club website (link above).

His best result was his second place in 1906, giving him an estimated rating of 2130: a strong club player at the time he gave up serious over the board chess (the 1911 Durban championship must have been a very brief comeback). The winner in 1906, Bruno Edgar Siegheim (1875-1952) was born in Germany, played chess in New York (1899-1904), South Africa (1906-1912) and England (1921-1926) before returning to South Africa. His best result was finishing 2nd= with Réti at Hastings in 1923, just half a point behind the great Akiba Rubinstein, which suggests he was IM strength.

We know very little about his life outside chess. It seems like he had enough money not to work and was able to devote his time to his hobbies. I presume he continued to play cricket in Durban, although newspapers from that period aren’t available online. There’s no archival record of Cecil ever having played first-class cricket.

What we do have is a couple of passenger lists.

A 1903 passenger list for a ship sailing from London to Port Natal lists Mr C A Lucas Bull (35), Mrs Bull (32), Miss B Bull (3), Mr C Bull (28). This looks like Cecil and his family visiting England and returning with Clifford, who was going to live with them in Durban. Cecil appears to have a wife and young daughter, but we have no further information about them.

A 1909 passenger list, again from London to Natal, offers Cecil Slade (sic) Lucas Bull, Eunice Chillingworth Lucas Bull and Bessie Lucas Bull. I have no idea where the Slade came from but it looks like he was married to Eunice and Bessie was their daughter.

He was still composing prolifically: here’s one from 1912.

Problem 2. Mate in 3: 1st prize winner Saale-Zeitung 1912

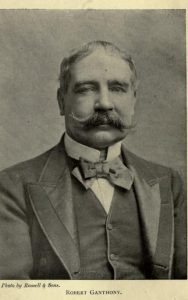

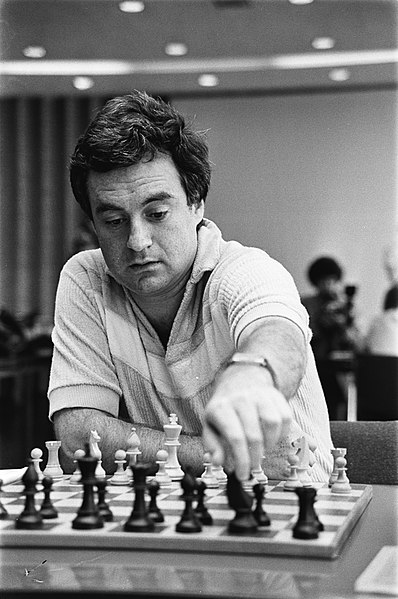

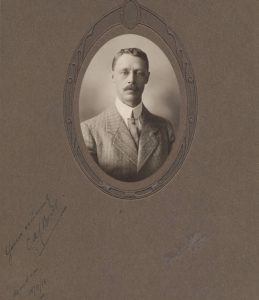

Here’s a photograph of him from 1913.

He continued composing successfully up until 1932, mixing heavyweight prizewinners with more lightweight offerings for the Natal Mercury. He died in Durban on 19 July 1935, at the age of 66.

Problem 3 is another first prizewinning mate in 3 from the latter stages of his career: British Chess Magazine 1931.

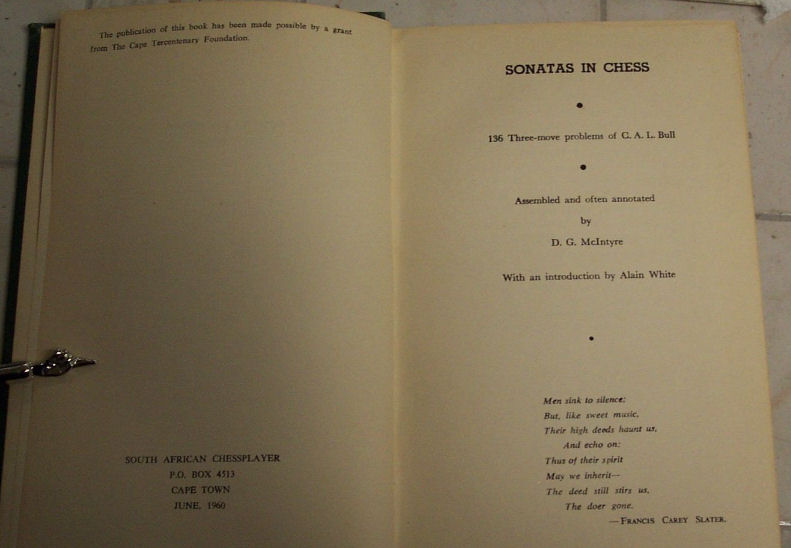

In 1960 Cecil’s friend and occasional collaborator Donald Glenoe McIntyre published Sonatas in Chess, a collection of 136 of his best threemovers (South African Chessplayer). This is a rare book and second hand copies go for high prices. I saw a copy for sale back in the 1980s but didn’t buy it – I really should have done.

I occasionally publish his more accessible problems on the Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club website: see here and here.

At present I have no idea about what happened to Eunice and Bessie. I can find no information about anyone with the forenames Eunice Chillingworth, and the 1927 London marriage of Bessie L Bull to Robert Douglas King-Harman isn’t the same person.

There’s a prominent South African businesswoman named Wendy Lucas-Bull, who is married to Clive Lucas-Bull, and whose father-in-law is, or was, Leslie Arthur Lucas-Bull. Any connection? If you have any further information about Eunice, Bessie or any other relation do let me know.

Cecil Alfred Lucas Bull, chess champion of Twickenham and Durban, and multiple prizewinning problemist, this was your life.

Join me again soon for another delve into the Twickenham Chess Club menagerie.

Sources and acknowledgements:

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk

Problems and solutions from Yet Another Chess Problem Database

EdoChess (Rod Edwards)

Cleveland Public Library Digital Gallery

Durban Chess Club website

Richmond & Twickenham Chess Club website

Thanks to Dr Tim Harding for The Chess Bouquet by Frederick Richard Gittins

Problem solutions:

1.

1.♕a1! ~ 2.♕e5+ ♔d3 3.♘e1# 1…♔d5 2.♕×a8+ 2…♔d6 3.♗e7# 2…♔c5 3.♗e7# (Model mate) 1…♔f5 2.♕b1+ ♔g4 3.♕e4# 1…♔d3 2.♕b1+ ♔c3 3.♗d2# (Model mate) 1…♖×g5 2.♕d4+ ♔f5 3.♘h4# (Model mate) 1…♘g4 2.♕d4+ ♔f5 3.♕d3# (Model mate)

Model mates were much valued at the time.

From Wikipedia:

A model mate is a type of pure mate checkmating position in chess in which not only is the checkmated king and all vacant squares in its field attacked only once, and squares in the king’s field occupied by friendly units are not also attacked by the mating side (unless such a unit is necessarily pinned to the king), but all units of the mating side (with the possible exception of the king and pawns) participate actively in forming the mating net.

2.

♗c8! ~ 2.♗×d7 ~ 3.♗e6# 1…♗b1 2.♕a1 A ~ 3.♘e7# B 2…d×c6 3.♗e6# 2…♔×c6 3.♗b7# 3.♕a8# 1…♗×b3 2.♘e7+ B 2…♔e5 3.♕a1# A 2…♔d4 3.♕e4# 2…♔c4 3.♕e4# 1…d×c6 2.♕×c6+! 2…♔d4 3.♕e4# 2…♔×c6 3.♗b7# 2…♔e5 3.♕d6# 3.♗c3# 1…♘f7 2.♘×d7 ~ 3.♘×b6# 3.♘f6# 2…♔e6 3.♘d4#

Some more model mates here, as well as sacrifices and corner-to-corner queen moves, something of which Bull was very fond.

3.

1.♕d8! ~ 2.h3+ ♔×h5 3.g4# 1…♖b4 2.♗×g6 ~ 3.h3# 1…♔×h5 2.♗d1+ ♘e2 3.♗×e2# 1…g5 2.♕d7+ 2…♔×h5 3.♕h3# 2…♔h4 3.♕h3# 2.♕c8+ 2…♔×h5 3.♕h3# 2…♔h4 3.♕h3# 1…g×h5 2.♕d4+ ♔g5 3.h4#