From the publisher:

“After his first two most successful volumes of Chess Middlegame Strategies, Ivan Solokov explores in his final volume ideas related to the symbiosis of the strategic and dynamic elements of chess. He combined the most exceptional ideas, strategies and positional play essentials. These three volumes will give you a serious head start when studying and playing a middlegame. A book and series that cannot be missed in any serious chess library!”

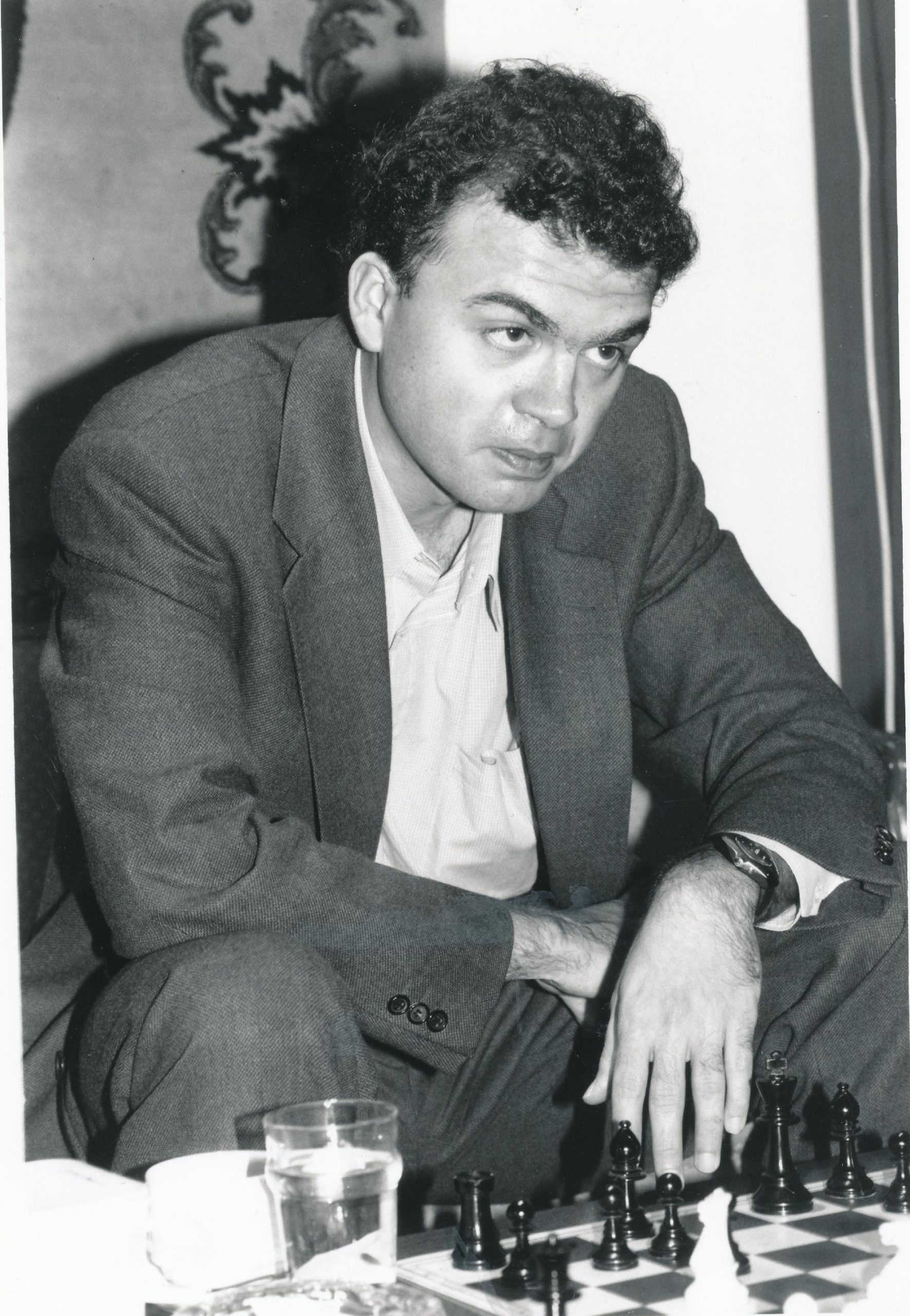

“Grandmaster Ivan Sokolov is considered one of the best chess authors winning many chess tournaments and writing many bestselling chess books. At the moment he is coaching worldwide the most chess talented youngsters.”

This interesting book has seven diverse chapters on middlegame strategies:

- Karpov’s king in the centre

- Geller/Tolush gambit plans & ideas

- Anti-Moscow Typical plans and ideas

- Space versus flexibility

- Positional exchange sacrifice

- Open file

- G-pawn structures

Chapters two and three do cover two sets of related positions and are rather specialised in terms of the opening. The other chapters are rather more generic in nature.

It is well known that opening preparation these days is very deep with the use of chess engines. Many variations of sharp openings played at the top level are effectively analysed to the end of the game now, for example resulting in a perpetual or an equal ending. Although this book does cover some games in sharp tactical openings, it does not make the mistake of providing a sea of complex variations with little explanation: Sokolov has made a good effort to extract out some of the key ideas in these dynamic battles.

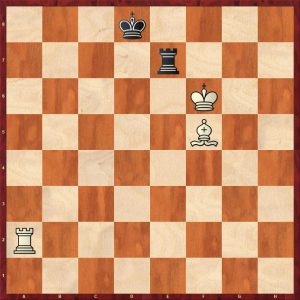

Chapter 1 Karpov’s king in the centre

Karpov employed the “king in the centre” idea in his favourite Caro-Kann defence. The celebrated game Kamsky – Karpov Dortmund 1993 shows this idea.

In the position white has more space and an intention to attack on the kingside, so white played 11.Qh4?! Black looks to have a problem with his king as castling kingside will be “castling into it” with white’s bishops and queen ready for action there. Karpov came up with an ingenious solution: 11…Ke7!

Suddenly black threatens 12…g5! and the white aggressively placed queen becomes a liability.

The idea only works because white’s queen is misplaced on h4 and is vulnerable to attack. In the famous game against Kamsky, white is really forced to sacrifice a pawn with 12.Ne5! Bxe5 13.dxe5 Qa5+ 14.c3 Qxe5+ when white has sufficient compensation but no more. 12.Bf4 is pretty insipid, after 12…Bb4+ 13.Bd2 Bxd2 14.Kxd2 Qa5+ 15.c3 c5 with equal chances.

The reviewer is not going to cover this game in detail in his review as this is a well known game. If the reader is not familiar with this game, then buy the book to get good coverage of an instructive struggle.

In subsequent games in this variation, white played 10.Qe2! keeping the queen centralised.

The reviewer was particularly impressed with the following game by Vishy Anand against Vladimir Kramnik in the World Championship match in Bonn 2008. Anand’s preparation and superior play in the Meran variation effectively won him the match. The book covers one of Anand’s wins in this variation using the “king in the centre” strategy.

Kramnik, Vladimir – Anand, Viswanathan

World Championship Bonn (5) 2008

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 e6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Bd3 a6 9.e4 c5

10.e5 cxd4 11.Nxb5 axb5 12.exf6 gxf6 13.0-0 13…Qb6 14.Qe2

This is a key position in just one of the main lines in the Meran variation.

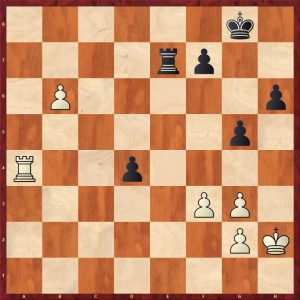

14…Bb7 (The main line, 14…b4 is interesting) 15.Bxb5 Rg8!? (Anand is the first to deviate from Game 3 which he won, and present Kramnik with a new surprise instead of 15…Bd6. Kramnik’s choice in the previous game was the natural 16.Rd1 Rg8 17.g3 Rg4 18.Bf4 Bxf4 19.Nxd4 At this moment Anand was an hour(!) up on the clock, but now he had his first long think 19…h5!? 20.Nxe6 fxe6 21.Rxd7 Kf8 22.Qd3 Rg7! 23.Rxg7 Kxg7 24.gxf4 Rd8 Kramnik – Anand WCh Bonn (3) 2008) 16.Bf4 Bd6 17.Bg3 Black has good counterplay on the g-file f5 (Anand continues to harass the Bg3) 18.Rfc1!? f4 19.Bh4

19…Be7! The bishop’s role on d6 is over, so it returns to free the e7-square for Black’s king 20.a4 Bxh4 21.Nxh4

Ke7! The possible threat to g2 again enters the equation. 22.Ra3

White boosts his third rank, but on the other hand disconnects his rooks and Black can turn his attention to the c-pawn. The radical 22.g3!? should be considered. This weakens the long diagonal, but removing the pawn from g2 enables White to play more actively, a possible line is 22…fxg3 23.hxg3 Rg5 24.Bxd7

24…Rag8! 25. a5 (25.Bb5?? loses to 25…d3 followed by Rxg3+) Qd6 26.Ra3

26…Rxg3+ 27.fxg3+ Rxg3+ 28.Rxg3+ Qxg3+ 29.Ng2 Bxg2 30.Qxg2 Qe3+ 31.Kh2 Qh6+ 32.Kg3 Qxc1=

Black will pick up the dangerous a-pawn with Qc7+ or Qg5+ leading to an unbalanced but roughly level ending.

Back to the game.

22…Rac8 23.Rxc8 Rxc8 24.Ra1 Qc5 25.Qg4

25…Qe5

Black intuitively keeps his queen closer to his king. Another interesting computer alternative is 25…Qc2!? to support the d4-pawn 26.Qxf4 d3!

and it’s already reasonable to bail out with 27.Nf5+ exf5 28.Re1+ Kf8 (28…Be4 leads to an equal ending) 29.Bxd7 d2 30.Qh6+ Kg8 31.Qg5+ with a draw by perpetual

26.Nf3 Qf6 This move is also connected with a hidden trap.

27.Re1 [27.Nxd4? Qxd4 28.Rd1 Nf6 29.Rxd4 Nxg4 30.Rd7+ Kf6 31.Rxb7 Rc1+ 32.Bf1 Ne3!-+ Surprisingly enough, this motif occurs later in the game!; harmless is 27.Bxd7 Kxd7 28.Nxd4 Ke7 29.Rd1 Rc4= Best is 27.Ne1! improving the knight. Kramnik still wants more and keeps the tension.] 27…Rc5!? 28.b4 Rc3 Setting a beautiful trap.

29.Nxd4?? (Black’s forces already exert unpleasant pressure, but the text-move is an unforced and decisive tactical miscalculation. 29.Nd2!? still leads to a murky position and the outcome of the game remains open.) 29…Qxd4 30.Rd1 Nf6! 31.Rxd4

Nxg4 32.Rd7+ Kf6 33.Rxb7 Rc1+ 34.Bf1

Ne3! winning 35.fxe3 (35.h3 Rxf1+ 36.Kh2 Rxf2-+) 35…fxe3 The pawn queens 0-1

Chapter 2 Geller/Tolush Gambit Plans & Ideas

Here is a an early Kasparov game which demonstrates white’s attacking potential in this line.

Kasparov – Petursson

Valetta 1980

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 dxc4 5.e4 b5 6.e5 Nd5 7.a4 e6 8.axb5 Nxc3 9.bxc3 cxb5 10.Ng5 Bb7 11.Qh5 Qd7

12.Be2

A previous Kasparov game went 12.Nxh7? (a well known blunder nowadays) 12…Nc6! Black leads in development and the tactics work for him as well. White is probably lost already!

13.Nxf8 Qxd4! leads to a huge advantage to black

Kasparov’s opponent missed 13…Qxd4!, played 13…Rxh5? and Kasparov went on to win

13.Nf6+? gxf6 14.Qxh8 also loses

14…Nxd4! 15.cxd4 Qxd4 16.Ra2 0-0-0 winning

Back to the main game

12…h6 13.Bf3

Nc6 (13…g6 weakens black’s kingside, after 14.Qh3 Nc6 15.Ne4 0-0-0 16.Be3! leads a white advantage)14.0-0 Nd8 Black is defending his weaknesses and avoiding the weakening g6 but his development is lacking 15.Ne4 a5

16.Bg5 (16.Qg4! was more accurate, 16…Rh7 17.Re1 and black has problems developing) Bd5 17.Rfe1 Nc6 18.Bh4 Ra7 19.Qg4

Rh7 20.Nd6+! Bxd6

21.Bxd5 (21.exd6 is very strong as well) Be7 22.Be4 g6 23.Bf6 Black’s rooks are horribly disconnected

Kf8 24.Qf3 Nd8 25.d5! Opening up files for white’s better placed rooks: black crumbles quickly exd5 26.Bxd5 Qf5 27.Qe3

Rd7 28.Rad1 Bxf6 29.exf6 Ne6 30.Be4 Rxd1 31.Bxf5 Rxe1+ 32.Qxe1 gxf5

33.Qe5! A lovely centralising move to win the game 33…Kg8 34.Qg3+ 1-0

Chapter 3 Anti Moscow Gambit Plans & Ideas

The reviewer shows one of the author’s fine wins.

Sokolov – Novikov

Antwerp 1997

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 c6 5.Bg5 h6 The Moscow Variation 6.Bh4 dxc4 7.e4 g5 8.Bg3 b5 The starting tabiya of the Anti-Moscow Gambit

9.h4!? (9.Be2 and 9.Qc2 are the main alternatives)

9…g4 (9…b4!? 10.Na4!) 10.Ne5 h5

10…Bb4 leads to a very complex game. 11.Be2 Nxe4! 12.0-0

12,,,Nxc3 13.bxc3 bxc3 14.Bxg4 Bxa1 15.Bh5 Qxd4 16.Qf3 Qxe5! 17.Bxe5 Bxe5 18.Qf7+ Kd8

Stockfish helpfully gives this as = (0.00) and gives a bizarre line 19.Re1 Bc3 20.Re3 Ba1 21.Re1= Who says computers don’t have a sense of humour?

Back to the main game

11.Be2

Bb7 (11…b4 is risky 12.Na4 Nxe4 13.Bxc4!) 12.0-0 Nbd7 13.Qc2 Bg7 14.Rad1 Qb6!? 15.Na4!

15…Qa5?!

Best is15…bxa4! 16.Nxc4 Qb4 17.e5 17…Nd5 18.a3 Qb3 19.Qxb3 axb3 20.Nd6+ Ke7 21.Nxb7 a5 22.Rc1

White is better, but black has got the queens off.

16.Nc5 Nxc5 17.dxc5 Qb4 18.Rd6 Qxc5 Black grabs another pawn

19.Rfd1 0-0 White trades off a key defender of the black king 20.Nd7! Nxd7 21.Rxd7 Qb6 (21…Bc8 22.Bd6 Qb6 23.Bxf8)

Black is completely passive. White just needs to bring his queen into the killing zone.

22.Qc1!+- 22…Bc8 23.Qg5! (Threatening 24.Be5) 23…Bxd7 24.Rxd7 (25.Be5 is a terrible threat)

24…Kh7 25.Qxh5+ Kg8 26.Bc7! 26…Qa6 27.Qxg4 Kh7 28.Qh5+ Kg8 29.Qg5 Kh8 30.Be5 Exchanging off the final bodyguard Bxe5 31.Qxe5+ Kh7 32.Qh5+ Kg7 33.Qg5+ Kh7

34.Bh5 1-0

Chapter 4 Space versus Flexibility

This section covers the technique of exploiting a space advantage in a common type of pawn structure shown below:

This structure can arise from a variety of openings such as the Caro-Kann, Scandinavian, French and the Meran system in the Slav.

White clearly has more space and quite often the bishop pair as black has exchanged off his white squared bishop.

White’s natural plan is to play c4 and d5 opening up the position for the bishop pair. The game shows a didactic game where white exploits his space advantage and skillfully transforms advantages.

Short – L’Ami

Staunton Memorial London 2009

1.e4 c6 2.Nc3 d5 3.Nf3 Bg4 4.h3 Bxf3 5.Qxf3 Nf6 6.Be2 dxe4 7.Nxe4 Nxe4 8.Qxe4 Qd5

9.Qg4 Nd7 10.0-0 Nf6 11.Qa4

White declines the exchange of queens again. Black can now force a queen exchange, but should he? White won the game without black making an obvious mistake. So this suggests that black should keep the queens on.

11…Qe4 12.Qxe4 Nxe4 13.Re1 g6 14.d4 Bg7 15.Bf3

15…Nf6 (15…Nd6 is another idea to hamper d5 from white 16.Bf4 Rd8 17.Rad1 Bf6 18.b3 Nf5 19.c3 h5 white can still play g4 with an edge)16.c4 White’s plan is straightforward, push d5

16…Rd8 17.Be3 0-0 18.Rad1 e6

19.g4! A typical space gaining move with the intention of kicking black’s knight away with g5 h6 20.h4?! (20.Kg2! was more accurate, see below) 20…Rfe8?!

20…h5!? would have given black better chances than the game, but white still retains good winning chances 21.g5 Ng4 22.Bxg4 hxg4 Black’s g-pawn will fall, but black has time to counterattack the d-pawn 23.Kg2 Rd7 24.Rd2 Rfd8 25.Red1 c5!

26.d5! (26.dxc5? leads to a clear draw Rxd2 27.Rxd2 Rxd2 28.Bxd2 Bxb2 29.Kg3 Kg7 30.Kxg4 f5+ Black draws as white’s extra doubled isolated pawn is not enough to win the bishop ending: see below)

26…exd5 27.Bxc5! b6 28.Be3 d4 29.Kg3 and white is winning the g-pawn with good winning chances, but there is work to do.

Back to the game.

21.Kg2 Do not hurry: improve the king, although 21.g5 also gains an advantage 21…Nd7 22.d5! At last the breakthrough

22…Ne5 23.dxc6 Nxf3 24.Kxf3 bxc6

White transforms his advantages: the bishop pair has gone but his better pawn structure and more active pieces prove decisive: first he grabs the d-file because of black’s weak a7-pawn

25.b3! a5 26.g5 (26.Bb6 is also good, but do not hurry: fix black’s kingside first limiting black’s kingside counterplay which is good technique) hxg5 27.hxg5 Ra8 28.Rd7 Bf8 29.Red1 a4 Hoping for play down the a-file 30.Rc7

axb3 31.axb3 Rec8 32.Rdd7 Rxc7 33.Rxc7 Rb8 34.Rxc6 Rxb3 35.Rc8 Winning a second pawn

f5 36.gxf6 Kf7 37.Ke4 Rb7 38.Bd4 g5 39.c5 Rb1 40.c6 Rc1 41.Be3 1-0

A really educational game.

Chapter 5 Positional Exchange Sacrifice

This chapter covers positional exchange sacrifices which is one of the key chapters in this book.

The most famous positional exchange sacrifice is probably Rxc3! in the Sicilian Defence. This is not covered in this book as it is so well known.

The following game covers an interesting exchange sacrifice in one of the old main lines of the Sicilian Richter-Rauzer variation. Kramnik’s concept in this game effectively killed off this line for white.

Ivanchuk – Kramnik

Dos Hermanas 1996

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 d6 6.Bg5 e6 7.Qd2 a6 8.0-0-0 h6 9.Be3 Be7 10.f4 Nxd4 11.Bxd4 b5 12.Qe3 Qc7 13.e5 dxe5 14.Bxe5

14…Ng4!? A new move at the time, and a very interesting idea, black sacrifices an exchange in order to get a strong initiative, when white loses many tempi with his queen (14…Qa5 is a sound alternative) 15.Qf3 15…Nxe5 16.Qxa8 (16.fxe5 Bb7 is better for black) 16…Nd7

Black has plenty of compensation for the exchange: a powerful pair of bishops and white will lose time with his queen.

17.g3? (17.Qe4 is probably best 17…Bb7 18.Qd4 Nf6 when black definitely has sufficient compensation with his great bishops) 17…Nb6 18.Qf3 18…Bb7 19.Ne4

19…f5!! (19…0-0 is good, but the move played whips up a powerful attack even more quickly) 20.Qh5+ 20…Kf8 21.Nf2 Bf6!

White has a dearth of pieces defending his king. Black now has a typical winning Sicilian attack against the poorly defended white king. Look at white’s pieces stuck on the kingside. Regaining the exchange by 21…Bxh1 was not necessary: play for mate!

22.Bd3 Na4 23.Rhe1 23…Bxb2+!

24.Kb1 24…Bd5! Bringing in the other bishop into the attack with decisive effect 25.Bxb5! (25.Bxf5 25…Bxa2+! 26.Kxa2 Qc4+ 27.Kb1 Nc3+ 28.Kxb2 Qb4+ 29.Kc1 Na2#)

25…Bxa2+! (Not 25…axb5?? 26.Rxd5 winning for white) 26.Kxa2 axb5 27.Kb1 (27.Rxe6? 27…Qc4+ 28.Kb1 Nc3+ 29.Kxb2 Qb4+ 30.Kc1 Na2#) 27…Qa5?

27…Qe7! was much stronger threatening 28…Nc3+ 29.Kxb2 Qb4+ 30.Kc1 Na2#,

28.Rd8+ giving up a whole rook is the only way to avoid immediate mate: 28…Qxd8 29.Re6 Bf6 wins

28.Nd3? (28.c3!! would have possibly held, when white can get to an ending a pawn down with drawing chances: buy the book to find out how) 28…Ba3!

White’s king is doomed 29.Ka2 (29.c3 Nxc3+ 30.Kc2 Nxd1 winning) 29…Nc3+ 30.Kb3 30…Nd5 31.Ka2 (31.Rxe6 31…Qa4+ 32.Ka2 Nc3+ 33.Ka1 Bc1#) 31…Bb4+ 32.Kb1 Bc3

0-1

A superb exchange sacrifice comfortably equalising. White could have held but defending a virulent attack over the board is nigh impossible.

Chapter 6 Open File

This section covers the topic of the open file. Many different types of position are demonstrated including pure attacking chess sacrificing a pawn or two or a piece to open files against an uncastled king.

Subtle positional struggles are also covered. In this latter vein, the reviewer was particularly impressed with a smooth win by Michael Adams shown below.

Adams – Wang

42nd Olympiad 2016 Baku 2016

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.Nxe5 d6 4.Nf3 Nxe4 5.d4 d5 6.Bd3 Nc6 7.0-0 Be7 8.Nbd2 Bf5

This is a main line in the Petroff Defence. White now exchanges some minor pieces to gain control of the e-file. White sometimes executes this strategy in the Ruy Lopez anti-Berlin variation.

9.Re1 Nxd2 10.Qxd2 Bxd3 11.Qxd3 0-0

This position looks pretty equal which is undoubtedly the case, however, white has a slight lead in development and control of the e-file which make white’s position easier to play. Recently Carlsen and other top players have played these types of positions to win with success. Black must defend very precisely as shown by this game.

12.Bf4 White chooses a plan that involves the exchange of bishops and retaining control of the e-file. An alternative plan is 12.c3 followed by queenside expansion with b4 12…Bd6 13.Bg3 Bxg3 14.hxg3 Qd7

15.Re3 Rfe8 16.Rae1 Rxe3 17.Rxe3 h6 (17…Re8?? runs into 18.Qf5! winning a pawn and the game, exploiting the weak bank rank)

18.Qb3 Rb8

19.Ne5 White exchanges knights to dominate the e-file Qd6 20.Nxc6 Qxc6 21.c3 a5 22.Qa3 b6 23.Qe7 White now dominates the e-file. What does white do next? The logical plan is to attack on the kingside by advancing the kingside pawns to expose black’s king and use white’s more active pieces to mate black. Black decides to pre-empt this plan by correctly creating counterplay on the queenside.

b5! 24.a3 b4 25.axb4 axb4 26.cxb4

Black is closer to the draw, but must be very precise to exchange off the queenside pawns.

Qc1+? (A natural check but this probably loses, 26…Qb6! was the exact move required: 27.Rf3 f6 28.Rc3 Qxd4! 29. Rxc7 Qd1+ 30.Kh2 Qh5+ with a draw by perpetual check) 27.Kh2 Qxb2

28.Rf3? (Gifting black a chance to save the game, 28.Qxc7 Qxb4 29. Re5! wins a pawn under favourable circumstances, although white must display some technique to convert) Rf8? (28…f6! draws viz. 29. Qxc7 Qxb4 30.Rf5 Qb6! forcing a queen trade 31. Qxb6 Rxb6 32. Rxd5 Rb2 33.f3 Rd2 with a drawn rook ending but black will have to demonstrate sound technique to hold this ending a pawn down) 29.Qc5 c6 30.Qxc6

So white has won a pawn: black may be lost even with best play, but he can make things difficult for white.

Qxd4? (31…Qxb4! 32. Qxd5 offers black chances to draw but the presence of queens makes things much harder for the defending side. With the queens off and black’s rook on d2, black would be drawing) 31.b5 This pawn runs very fast, the d-pawn offers no real counterplay Qe5 32.b6 Re8 Black threatens mate in two

33.Rf4 Qe6 34.Qb7?!

blocking the passed pawn doesn’t look right. More accurate for white was 34.Qc7! After 34…Qe7 we reach:

35.Qa7! wins nicely, for example 35…Qxa7 36.bxa7 Ra8 37.Ra4 White’s king is in the square of the d-pawn, so black is totally lost.

34…g5 35.Ra4 Qe2? (35…Kg7 getting the king off the back rank was the only hope to fight on) 36.f3 d4

37.Ra8 was quicker and more forceful, 37…d3

38.Qc6! Rxa8 38.Qxa8+ Kh7 39. b7 d2 40.b8Q d1Q 41.Qg8#

37.Qd7 Qe7 38.Qxe7 Rxe7

39.Ra7! The b-pawn costs black his rook 1-0

An instructive win with white elegantly exploiting a very small advantage. Notice how one mistake on move 26 loses black the game. It is surprising that black is already in the “zone of one mistake” from a seemingly innocuous opening.

Chapter 7 G-Pawn Strategies

This section covers the early aggressive push of the g-pawn against a castled king. This occurs in many different openings.

The Neo-Steinitz is not popular in modern GM praxis although Keres and Portisch did play this opening. Mamedyarov is a very aggressive player who plays the Neo-Steinitz. The following game is a slugfest.

Grischuk – Mamedyarov

Hersonissos 2017

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 d6

5.0-0 Bd7 6.Re1 (6.d4, c3 or c4 are more common) g5! This idea is perfectly sound, it was introduced by Portisch in 1968 against Kortschnoi.

7.Bxc6 (7.d4 is possible but will probably transpose into the game) bxc6! 8.d4 g4 9.Nfd2 exd4 10.Nb3

10…Ne7 (10…c5 is too greedy, after 11.c3 white has plenty of compensation for the pawn) 11.Nxd4 Bg7 12.Nc3 0-0 13.Bg5 f6 14.Be3 Qe8

Black will move his queen over to the kingside and push his pawns for a direct attack

15.Qd3? This move and the next just lose time, clearly white was unsure of his correct plan 15…Qf7 16.Qd2 Qg6 (16…c5! 17.Nde2 Bc6 followed by f5 looks great for black) 17.Bf4 h5

18.b4 h4 19.a4 Qh5 20.Be3

h3 (20…f5! was perhaps even stronger: 21.exf5 h3! 22.Ne4 hxg2 23.Ng3 Qh3 the main threat is to move a rook to the h-file) 21.Nce2! (21.g3 fails to 21…f5 22.Bf4 fxe4 23. Rxe4 Qf7 with 24…Ng6 to follow and white crumbles) hxg2

22.Nf4 Qh7!? An exchange sacrifice, 22…Qf7 was also very good for black 23.Nfe6 Bxe6 24.Nxe6

Ng6! The knight is heading to f3 25.Nxf8 Rxf8 26.Bf4! (26.Ra3 f5! 27.Bd4 f4 and black’s attack is crashing through) f5 (26…Nh4 is answered by 27.Ra3) 27.exf5 Nh4

28.Ra3?

The final mistake, 28.Qd3! was essential and white can just save the game, one line is 28…Bxa1 29. Rxa1 Rxf5! 30.Bg3 Nf3+ 31. Kxg2 Qh3+ 32.Kh1 Rf6! Threatening Rh6

33.Qe4! Kf8 34.b5! Qh5! 35.Kg2! Rh6 36.Qf4+ Kg7 37.bxa6 Qh3+ 38.Kh1 Re6 39.a7 Ne1 40.Qg5+ Kh7 41. Qf5+ Kg7 draw by perpetual

28… Qxf5 29.Bg5 Nf3+ 30.Rxf3 gxf3 31.Bh6

31…Qd5?

A mistake 31…Qf6 forces a winning rook ending: 32.Bxg7 Kxg7 33. Qd3 Rh8 34.Qe4 Qh4. 35.Qe7+ Qxe7 36.Rxe7+ Kg6 37.Re3 Rf8 winning

32.Qc1 (32.Qe3! gives white some hope) Bc3 33.Re3 (33.Rd1 also loses Qh5 34. Rd3 Be5 35.Qg5+ Qxg5 36.Bxg5 Rf5 37.Bh4 Kf7 winning) Bd4 34.Rd3 Re8

35.c3

35.Be3 leads to a lost queen ending 35…Bxe3 36.Rxe3 Rxe3 37.fxe3 Qc4

The threat of 38…Qe2 is decisive.

35… Bxf2+ 36.Kxf2 Re2+

The checks run out after 37.Kg1 Qxd3 38.Qg5+ Kf7 39.Qg7+ Ke8 40.Qf8+ Kd7 and the black king escapes to b7 0-1

This book is aimed at grades 160+ players although aspiring players with lower ratings would benefit from reading this book.

To summarise, this is an good read with lots of educational games demonstrating the themes in each chapter. My only minor criticism is chapters 2 & 3 are very specialised handling middlegames from two particular opening systems. The other chapters handle more generic themes.

FM Richard Webb, Basingstoke, Hampshire, 5th July 2021

Book Details :

- Hardcover : 326 pages

- Publisher:Thinkers Publishing; 1st edition (17 Dec. 2019)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:949251060X

- ISBN-13:978-9492510600

- Product Dimensions: 17.02 x 1.27 x 23.37 cm

Official web site of Thinkers Publishing