We remember Anthony Dickins who passed away this day (Wednesday, November 25th) in 1987.

Anthony Stewart Mackay Dickins was born at 1 Rivers Street, Bath, Somerset on Sunday, November 1st, 1914. On this day was the Battle of Coronel — The Royal Navy suffered its first defeat of World War I, after a British squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock met and was defeated by superior German forces led by Vice-Admiral Maximilian von Spee in the eastern Pacific.

Anthony’s parents were Frederick and Florence Dickins (née Mackay) Frederick was a Captain in the Royal Artillery and was born on 25th November 1879, commissioned on May 26th 1900. He became a Colonel on 26th May 1930 and retired November 25th 1936. He was alive in 1972 (aged 92) and living in Bexhill passing away aged 101/102. He was awarded the CIE which is “Companion, Order of the Indian Empire in 1914”.

Anthony was baptised on December 29th in Seend, Wiltshire. Anthony had a brother Frederick James Douglas born in 1907 who married Nellie or Peggie Moist (records are unclear).

It would appear that Florence and Anthony (aged 5) travelled to Bombay from Plymouth on board the SS City of York (Ellerman Lines) departing December 26th, 1919 presumably to visit his father in India. The ships master was J. McKellan.

At the time of the 1939 Census Anthony was residing in the Tavistock Hotel in Tavistock Square. His occupation was given as journalist and editor and described as single.

From the Hull Daily Mail (extant and renamed Hull Live) of March 4th, 1939 we have this part review of a magazine called The Joys of Poetry. Anthony was the editor :

He died in Lambeth Wednesday, November 25th) in 1987. We have yet to determine where he was buried or cremated.

From http://chesscomposers.blogspot.com/2012/10/november-1st.html :

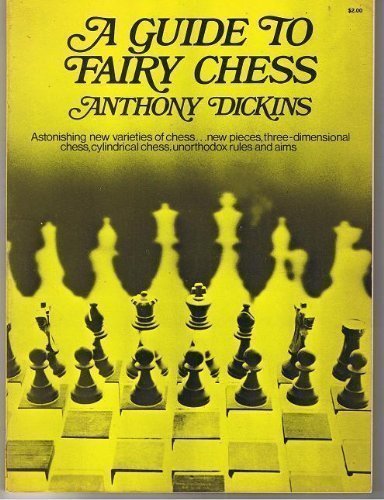

“Anthony Dickins wrote A Guide to Fairy Chess (1967) and other books about fairy chess. He edited the column of non-original fairy problems for “The Problemist”. He was specialized in constructional problems and was also an International Judge.”

From British Chess (Pergamon Press, 1984), Botterill, Levy, Rice and Richardson :

(article by ASMD and edited by JM Rice)

“Chess first entered my life seriously about 1950 at the well-known Mandrake Social and Chess Club in Meard Street, Soho, run by Harold Lommer and Boris Watson. Purely literary connections took me there in the first place, as it was a rendezvous for the literary fraternity, such as Dylan Thomas, David Gascoyne and others.

After the war Harold converted a small wine-vault into a tiny cramped chess-room, with some dozen tables and boards. Many well-known

personalities in the world of Chess were occasional visitors, such as Grandmasters Ossip Bernstein, Paul Keres, Jacques Mieses and Friedrich Sämisch; British Champions Willy Winter, Bob Wade and Dr. Fazekas; M. J. Franklin, now a British Master, and the Problemists, Dr. E. T. O. Slater and B. J. da C. Andrade. Mieses was then in his late eighties and charged a fee of half-a-crown (12.5 pence) for a game. When his name was mispronounced ‘Mister My-ziz’ he would say ‘I am Meister Mieses, not Mister My-ziz’.

Sämisch once played fourteen of us blindfold, defeating all except one, a very strong Indian player, Atta, who obtained a draw. My regular ‘partners’ were Vicki Weiss, the famous cartoonist, his brother Oscar, Richard Crewdson, Mr Keller (a professional who played sharply for a shifty shilling), Brian Mason, Colin ‘Puffer’ Evans, (whose strategy was to puff cigarette ash and smoke all over the board to bemuse the opponent) and Bob Troy (who always fell fast asleep immediately after making each move and had to be wakened on his next turn to play). There was a juke-box in the next room constantly blaring forth pop and bop. Most of all I played with Alex Distler, and with him always’variants of the game’ like Cylindrical Chess, Rifle Chess, Progressive Chess, or the Losing Game.

In this colourful and inspiring, if rather smoky and noisy, atmosphere I composed my first six chess problems, helpmates and cylindricals, though I did not then know of the existence of Problem books or magazines, nor had I heard of Sam Loyd, Max Lange, or T. R. Dawson when the Mandrake closed in the late fifties and Harold Lommer retired to Spain to write his two monumental works on Endgame Studies.

For the next 10 years or so I played at the West London and Athenaeum Chess Clubs, for Middlesex County and at Hastings congresses, meanwhile regularly solving the problems in the two evening newspapers for practice.

In 1965, in my 51st year, I discovered chess-problem magazines and the British Chess Problem Society, and was soon asked by John Rice to join the Fairy

Chess Correspondence Circle, whose director, W. Cross, perhaps the greatest solver of all time, guided my early footsteps in fairyland. At this point I compiled for my own use a summary of all the usual rules and conventions in Fairy Chess, as these were numerous and complicated. It occurred to me that a few other people might also welcome such a summary, so I put it into book form as A Guide to Fairy Chess, which I published by myself in 1967 under the imprint ‘The O Press’, a pun on the name ‘Kew’ where I was then living.

To my amazement it had rave reviews (‘the comprehensive work, so long awaited’, ‘more like an encyclopaedia’, ‘the bible of Fairy Chess’) and sold like hot cakes, going into three editions, each one enlarged and revised, the third produced by Dover Publications, New York, in 1971. Two years later I edited Dover’s publication of T. R. Dawson’s Five Classics of Fairy Chess.

In 1970 I flew to the States to spend a few days in the J. G. White collection in Cleveland, Ohio, researching historical material on Fairy Chess. This Ohio collection has the largest chess library in the world, and to my surprise I found that it contains also ‘every book or article ever written on or about ‘Omar Khayyam and Alice in Wonderland . To find oneself suddenly and unexpectedly transported, as if by magic carpet, into a superbly organised library with the most complete collections in the world of the three subjects that happen to be one’s own three principal literary interests is an experience that must approach closely to entering Nirvana, and I am happy to have had it. This visit enabled me to write A Short History of Fairy Chess (1975) and to give the lecture Alice in Fairyland to the Lewis Carroll Society in London, published in their journal Jabberwocky and reprinted by myself in 1976 (2nd edn 1978) .

In 1972 I decided to present my (by then) extensive collection of Fairy Chess books and magazines to my old university library at Cambridge to prevent the possible break-up of the collection as a single unit, and to ensure that at least one fairly complete Fairy Chess collection was retained in Britain.

In 1968 I was invited to open a Fairy Chess section in The Problemist, organ of the BCPS, which I handed over to Dr. C. C. L. Sells in 1970, and from 1974 to 1981 I ran another column in that magazine called ‘Other Types’. This chess journalism has brought me into touch with many problemists, and made many friends for me, in foreign countries.

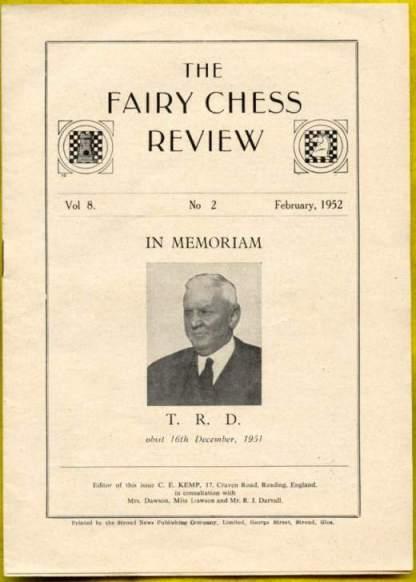

In 1967, on a visit to Mannheim for the Schwalbe annual meeting, I met Wilhelm Karsch, then editor of Feenschach, and in 1968 in Munich I again met Dr. Karl Fabel, whom I first came to know in London in 1967, and also Peter Kniest, one of the two present editors of Feenschach. In 1969, on a visit to Paris, a meeting was arranged for me at the late Jean Oudot’s flat, with Pierre Monr6al, J. P. Boyer, F. de Lionnais (author of the Dictionnaire des Echecs) and other French problemists, and altogether I have attended twenty three major problemist meetings in various countries, including FIDE meetings in The Hague, Wiesbaden, Canterbury and Helsinki. It has been my constant aim to try to encourage and cultivate the practice and study of Fairy Chess and to keep alive the great legacy that T.R. Dawson left to the world when he died in 1951.

In recent years I have developed close relations with the younger generation of West German problemists, who are very active in Fairy Chess, centred round 29-year-old Bernd Ellinghoven, who helps Peter Kniest to edit Feenschach and who printed my last booklet, Fairy Chess Problems (1979), containing poems as well as problems, combined in a new kind of fairy technique, for I believe that Fairy Chess represents in many ways the ‘poetry’ of Chess.

For the 50th birthday of T. R. Dawson on the 28th November 1939 a certain Dr Lazarus of Budapest wrote in Fairy Chess Review: ‘T. R. D. these three letters represent a conception in the Poetry of Chess which is amongst the most ingenious of all its turns, one of its most strange and interesting phases… Without T.R.D. human culture would lack a factor in its development’. Those people (and there are some) who would banish Fairy Chess altogether from Caissa’s realm resemble the iron-hearted Mr. Gradgrinds who would abolish romance, mystery, poetry, invention, discovery and imagination from human life.

Elsewhere I have written: ‘The Game for Murderers, The Problem for Philosophers, Fairy Chess for Sufis’, because the aim of the game-player is to ‘mate’ (kill) the opponent (from Arabic, mat _ dead), while the problemist has no personal opponent to kill, but merely a philosophical problem to resolve. In Fairy Chess, however, the adept is transported to another plane of existence, to an ‘undiscovered country from whose bourne no traveller returns’,to new’dimensions’ of thought (as in 3- and 4-dimensional problems) – in short, to Fairyland, to Nirvana.

The three problems represent my early, middle and later compositions. The helpmate in three moves (Black plays first in a helpmate) is a miniature culminating in an ideal Mate. C. H. O’D. Alexander was much tickled by what he called ‘the deceptive pawn’ on a2, which unexpectedly does not promote.

The Construction Task with 113 White moves, all ‘maintaining’ the legal stalemate position in which Black finds himself, is a standing record that defeated the previous record of 112 such moves obtained independently by six problemists in six countries, one of them an lnternational Master of FIDE.

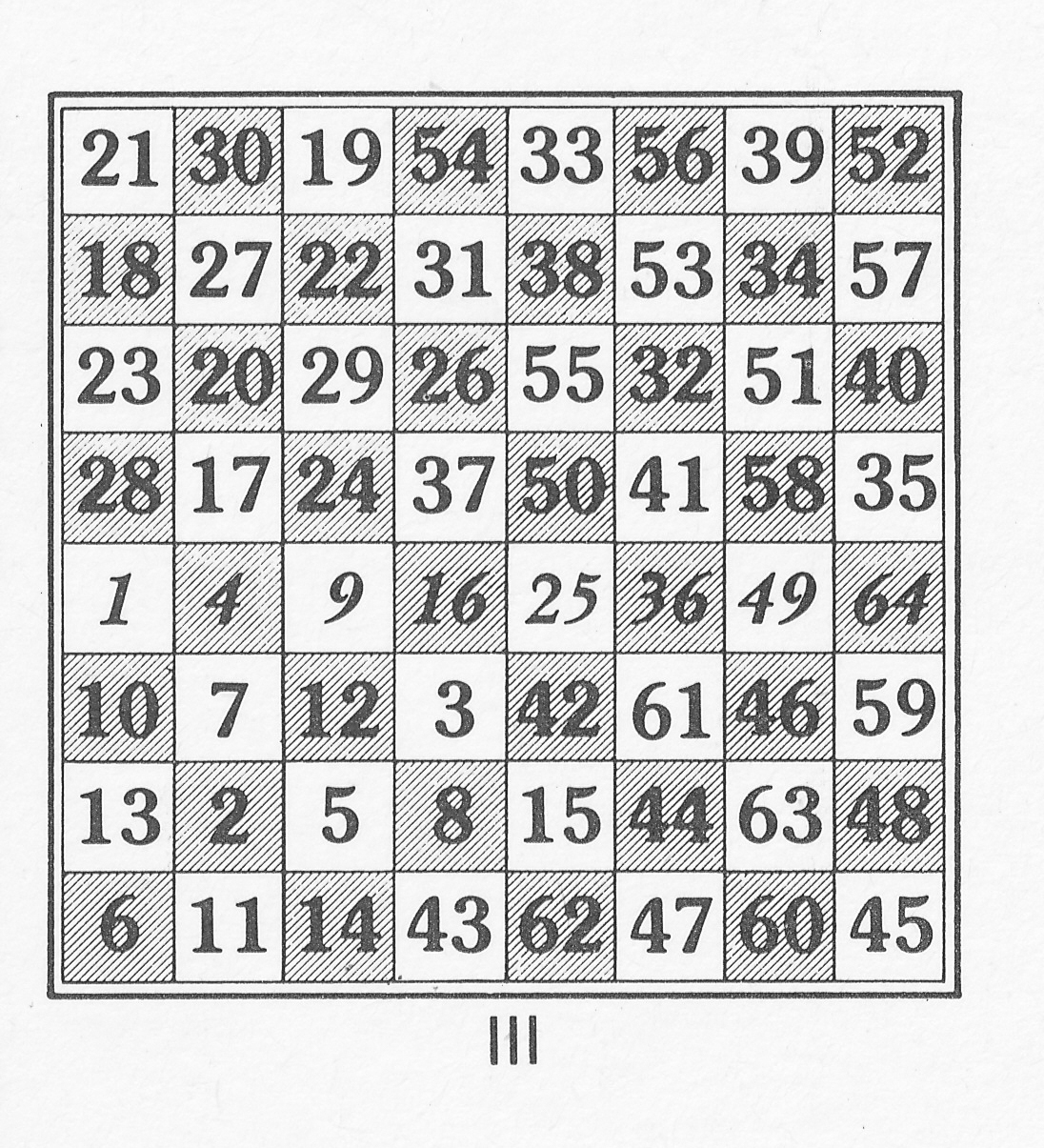

The Knight’s Tour is one of the oldest genres of Fairy Chess, dating from the earliest days of chess, and in TR Dawson’s Fairy Chess Review he published many of them., including some that showed the ‘square numbers’ (1,4,9,16,25,36,49,64) all on one rank – in the present example I have added the extra strict condition that as many as possible of the numbers 1 to 16 must be in the SW corner and as many as possible of the numbers 1 to 32 must be in the W half of the board.

For two reasons the perfect ideal in this task cannot be attained, firstly because of the given position of the number 25, and secondly because it is not possible to make a Knight’s tour on a 4 x 4 board in the SW corner.

Solutions :

1. Helpmate, Evening News, 20th February 1957 dedicated to Harold Lommer

Helpmate in 3 moves

1. Kd5 Nb1

2. Kc4 e8=Q

3. Kb3 Qb5 mate

2. Construction Task Record, Feenschach 9341 Sep/Oct 1969 dedicated to Karl Fabel

113 unforced stalemate maintenances with Promotion in Play (Pawn promotions count as 4 moves) unforced as W has some moves that do not maintain stalemate, so he is not ‘forced’ to maintain it.

3. Knight’s Tour Chessics 5(180) July, 1978 dedicated to D. Nixon.

Knights tour with

a) All square number on 4th rank

b) maximum of 1-16 in SW quad

c) maximum of 1-32 in W half

From The Encyclopaedia of Chess (Batsford, 1977), Harry Golombek OBE, John Rice writes:

“British problemist, Founder of Q Press (1967) to publish books on fairy problems: A Guide to Fairy Chess (1967); An Album of Fairy Chess (1970); The Serieshelpmate (co-author, 1971). Has presented a large collection of problem books to Cambridge University Library. International Judge (1975).”