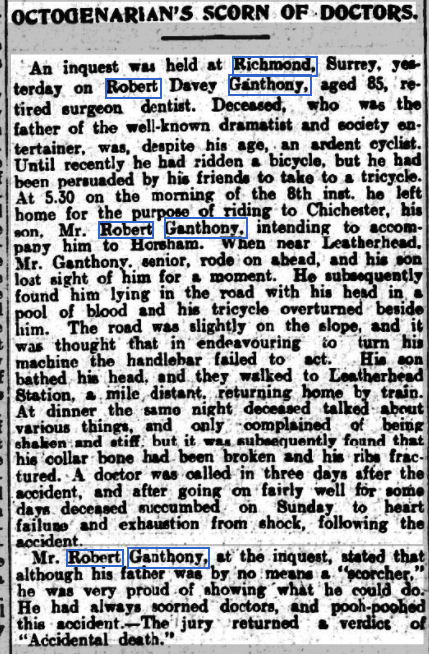

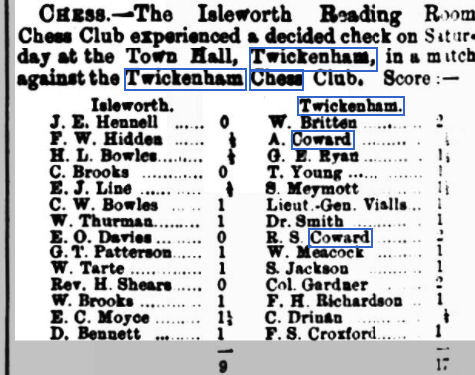

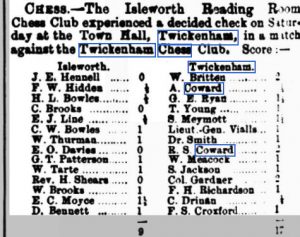

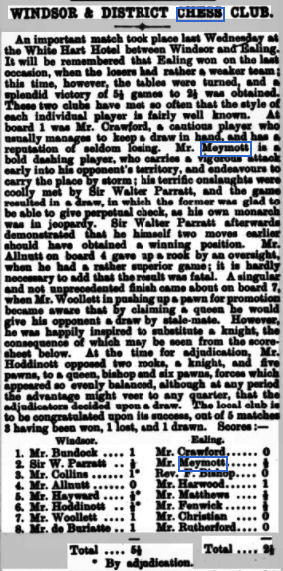

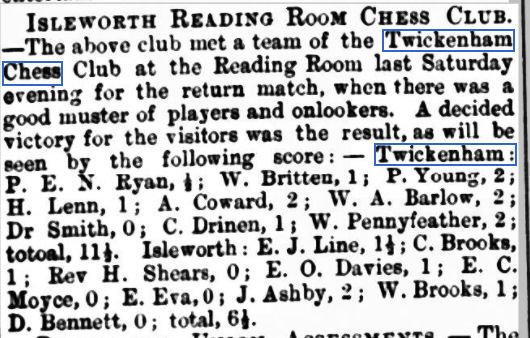

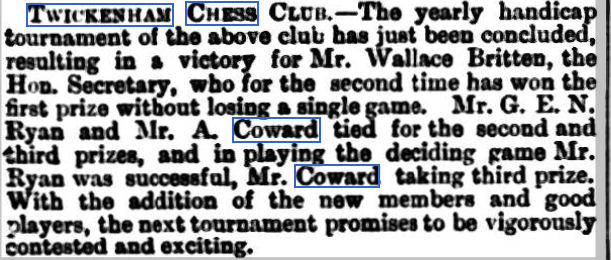

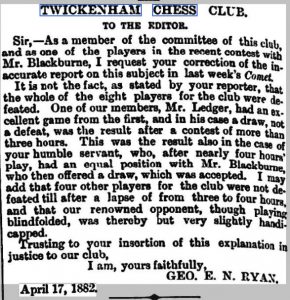

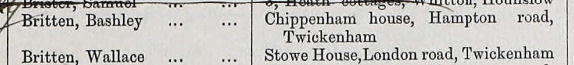

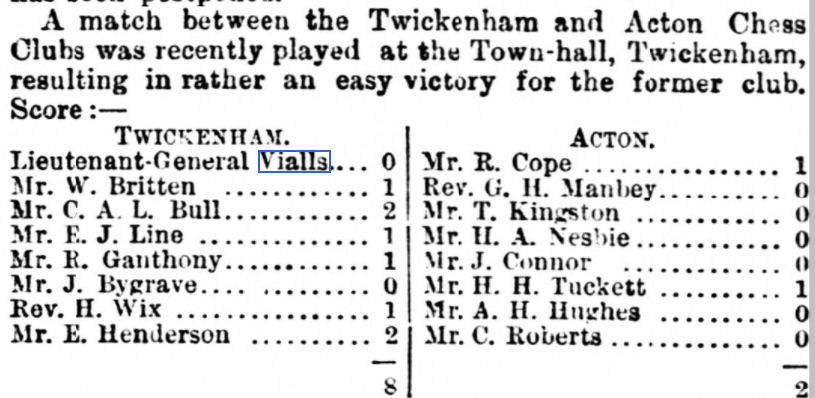

Surrey Comet 5 March 1887

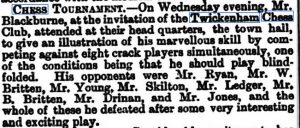

If you’ve been paying attention you’ll have seen this before. I’d like to draw your attention to Twickenham’s Board 3, Mr. C. A. L. Bull.

In the world of over the board chess he was a Minor Piece, but in the rarefied world of chess problems he was undoubtedly a Major Piece. It’s not so easy, though, to piece together his life as there appear to be no genealogists in his immediate family.

Let’s take a look.

We’ll start with his paternal grandfather, Benjamin Bull. Ben was born in Market Harborough, Leicestershire, a town we’ll have occasion to visit again, but I haven’t as yet found any family connections with other chess players whose family came from that area.

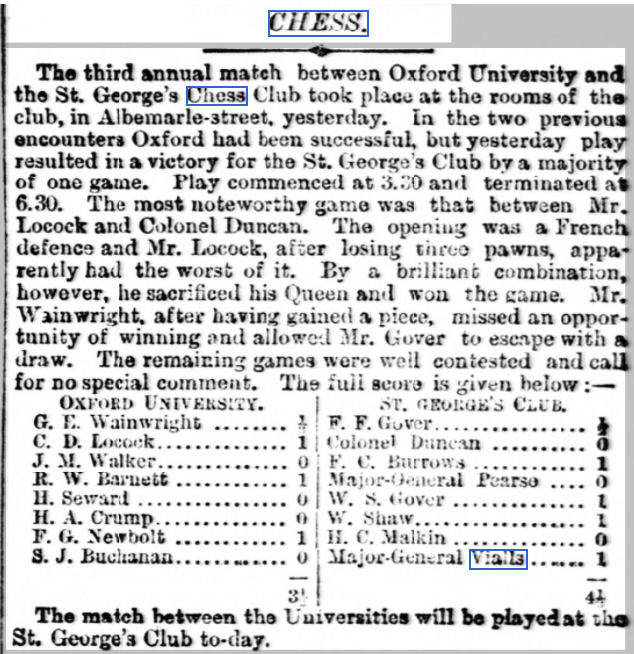

He was a hotel proprietor and we can pick him up in the 1851 census running the Castle Hotel in Richmond, which was demolished in 1888, but its successor would, in 1912, be the venue of the British Chess Championships. It’s quite possible a future series of articles will enable us to meet some of those who visited our fair Borough in 1912 to push their pawns around wooden chequered boards.

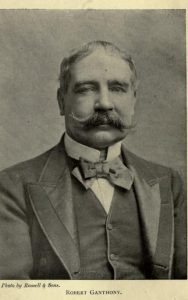

Ben and his wife Mary Ann had five sons and a daughter. One of their sons, Richard Smith Bull, achieved some fame as an actor using the stage name Richard Boleyn, but our story continues with another son, Thomas Bull.

Tom, by profession an auctioneer and surveyor, was born in 1839, and, in 1865, married the 18 year old Julia Sellé, daughter of William Christian Sellé, doctor of music, composer, and Musician in Ordinary to Queen Victoria. Their first child was born in Ramsgate, Kent, but they soon settled, like all the best people, in Twickenham. Tom and Julia had 11 children, one of whom died in infancy, and it’s their fourth son, Cecil Alfred Lucas Bull, who interests us.

He was born (as Cecil Lucas Bull: he would sometimes be known as Lucas Bull) in the second quarter of 1869 and baptised (now Cecil Alfred Lucas) at St Mary the Virgin Church, Twickenham on 16 June that year.

In the 1871 census we find Tom and Julia, with four young children, Julius, Alan, Cecil and Beatrix, living in Sussex Villa, Clifden Road, Twickenham, close to the town centre. They must have been well off as they could afford to employ no less than four servants, a cook, a housemaid and two nurses to look after their rapidly expanding family.

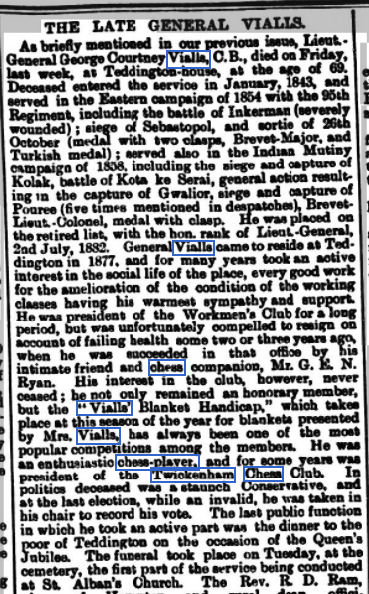

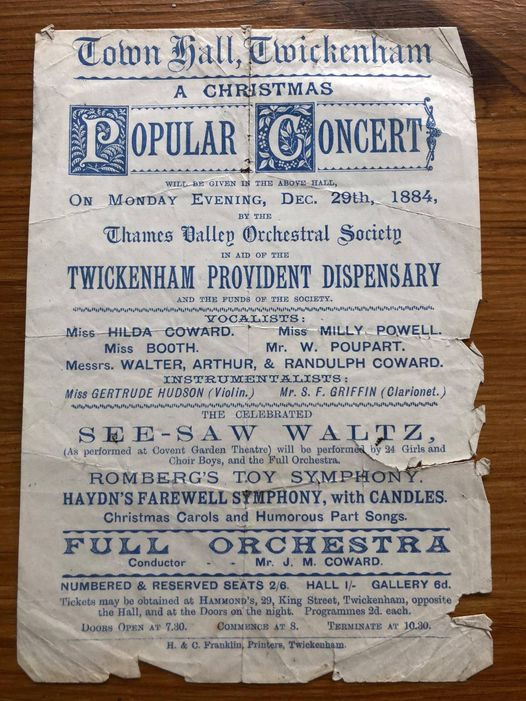

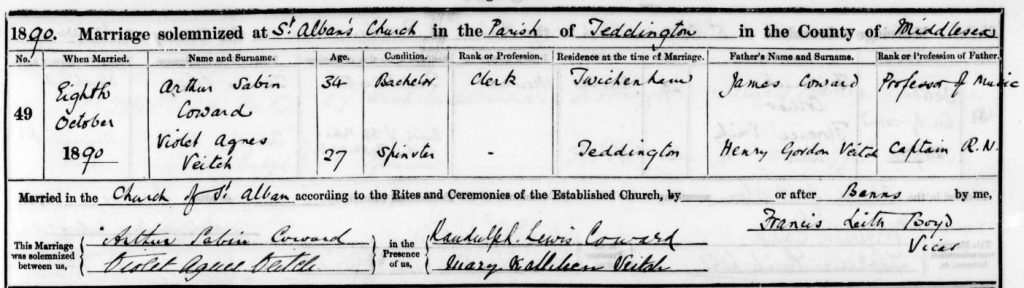

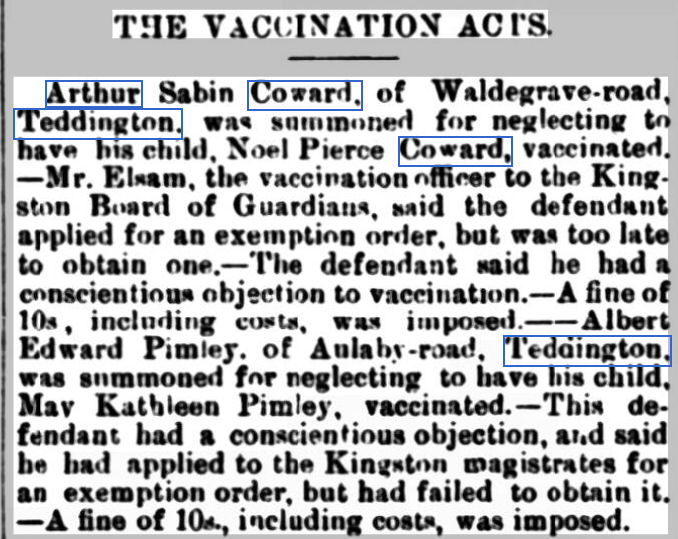

In round about 1875 the family moved from Twickenham to Ferry Road, Teddington, just across the road from where, a few years later, St Alban’s Church would be built, and where Noël Coward’s family would both worship and entertain.

The 1881 census records Tom and Julia in Ferry Road, now with Julius, Alan, Cecil, Beatrix, Maud, Gwynneth, Clifford, Walter and Allegra, along with a nurse, a cook, a housemaid and a parlourmaid. Life must have been good for the prosperous Bull family.

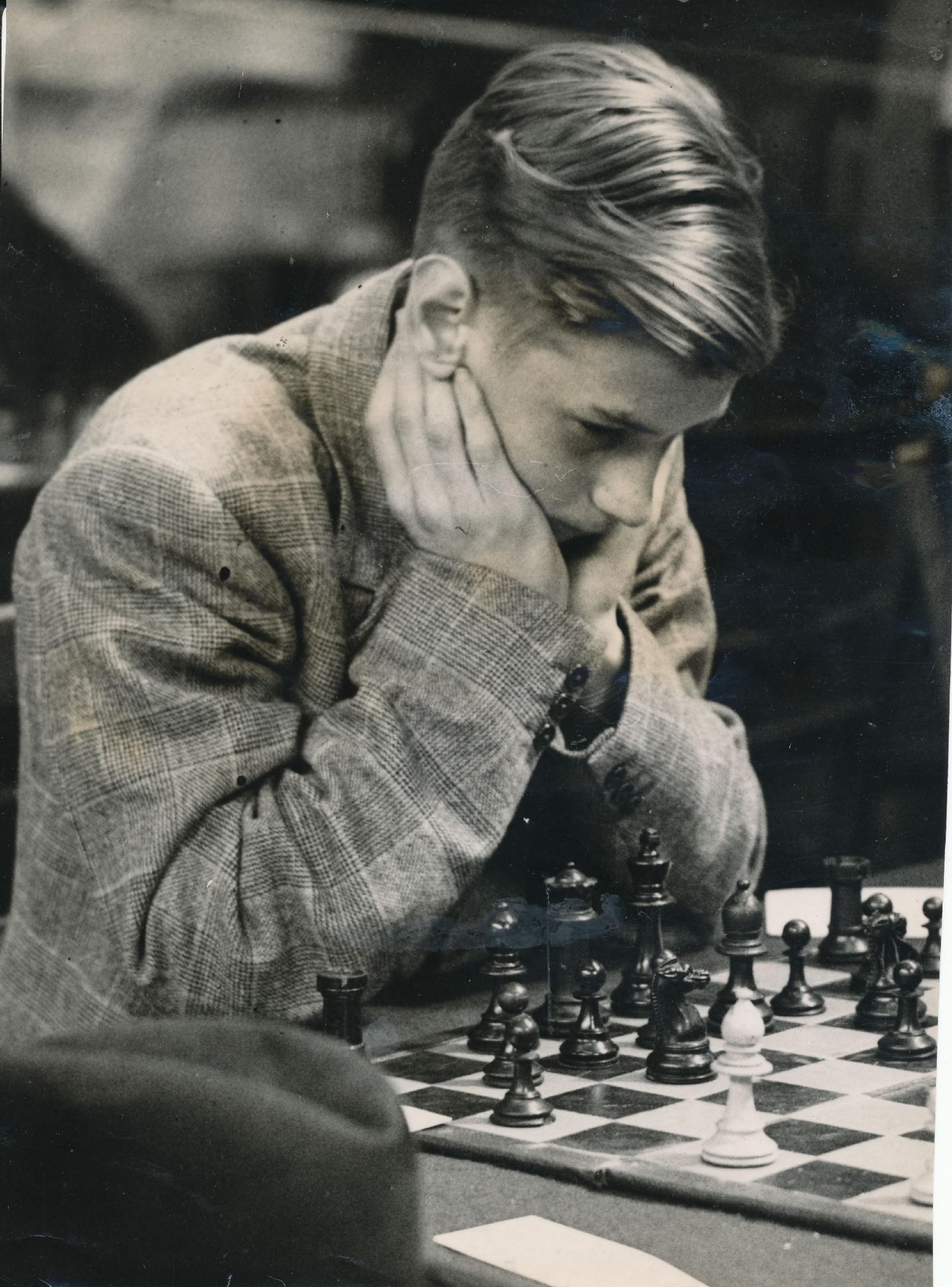

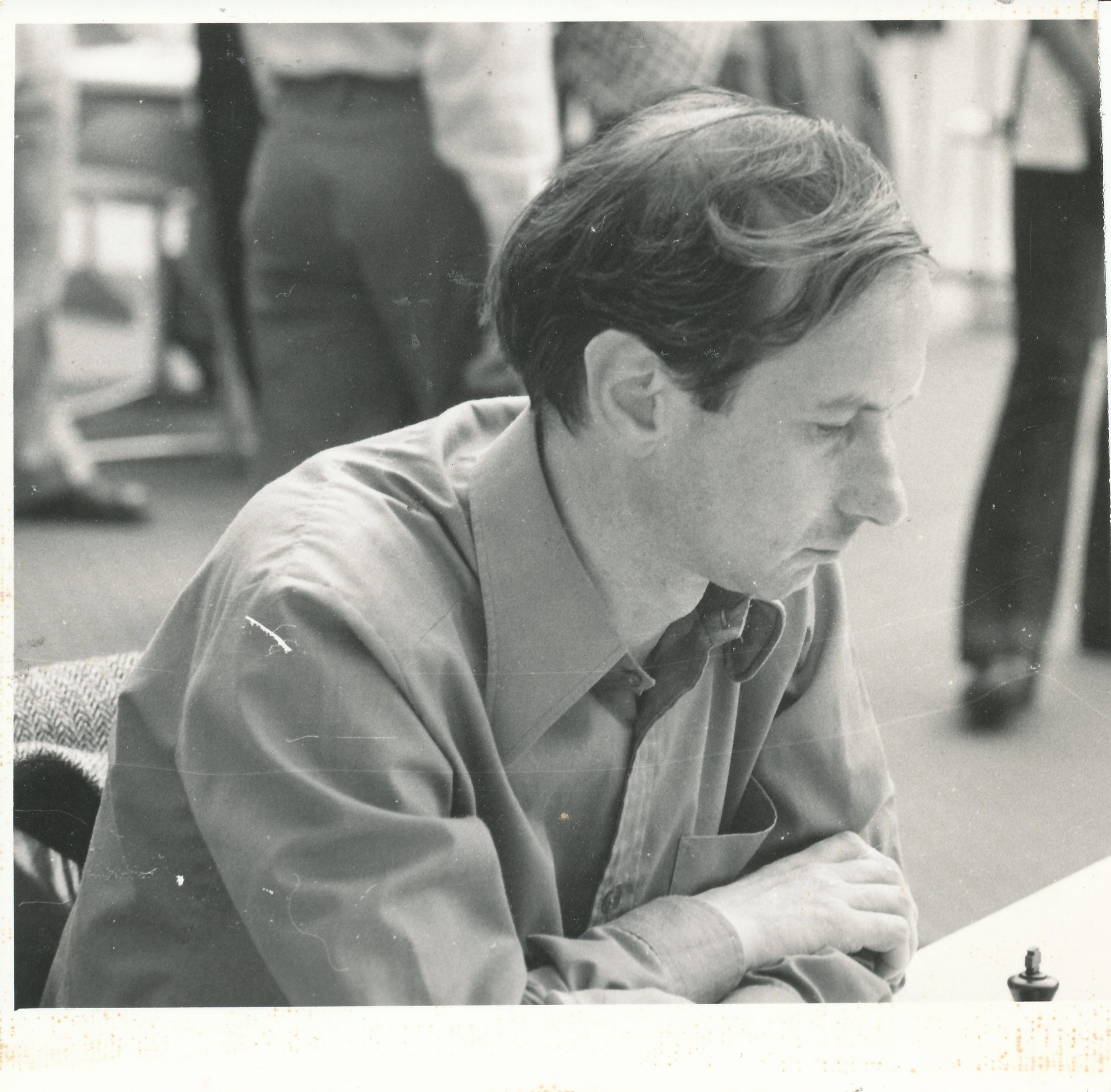

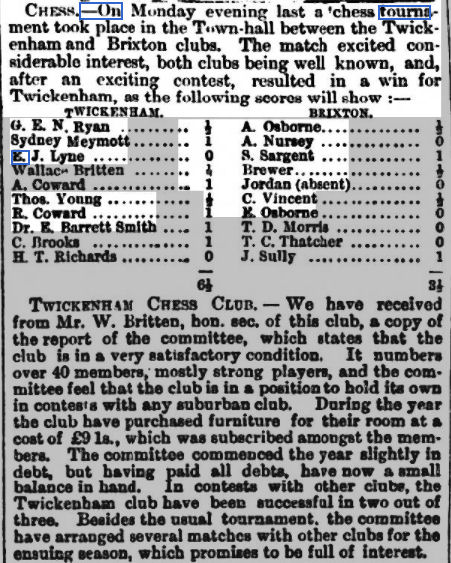

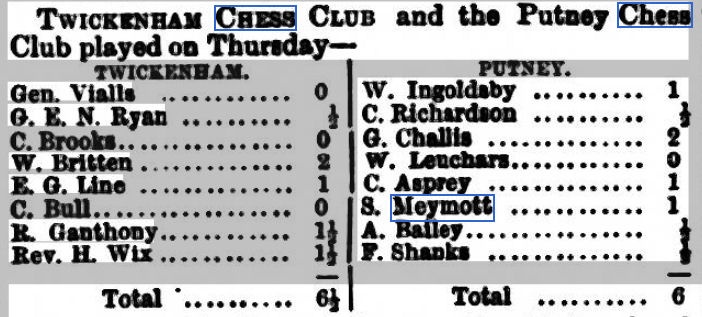

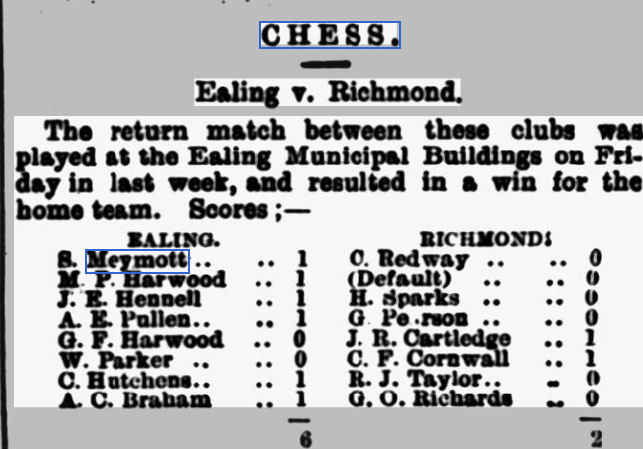

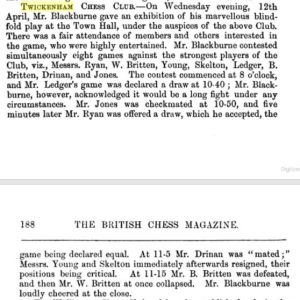

This tells us that young Cecil (I think they missed a trick by not adding Ferdinand to his name, making him Bull, CALF) was only 17 when he first represented Twickenham Chess Club. Not exceptional today, but it would have been very unusual, although I haven’t found any specific reference to his youth, at the time. Playing on third board and winning both his games, he must already have been a more than useful player. He went on to win the club’s handicap tournament on two occasions, playing off scratch.

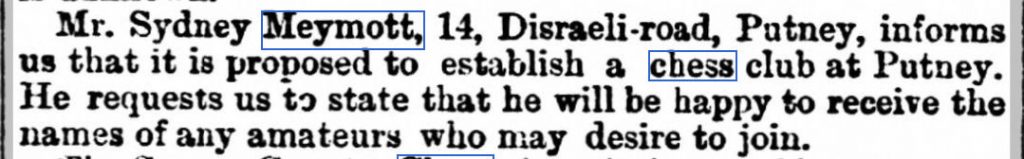

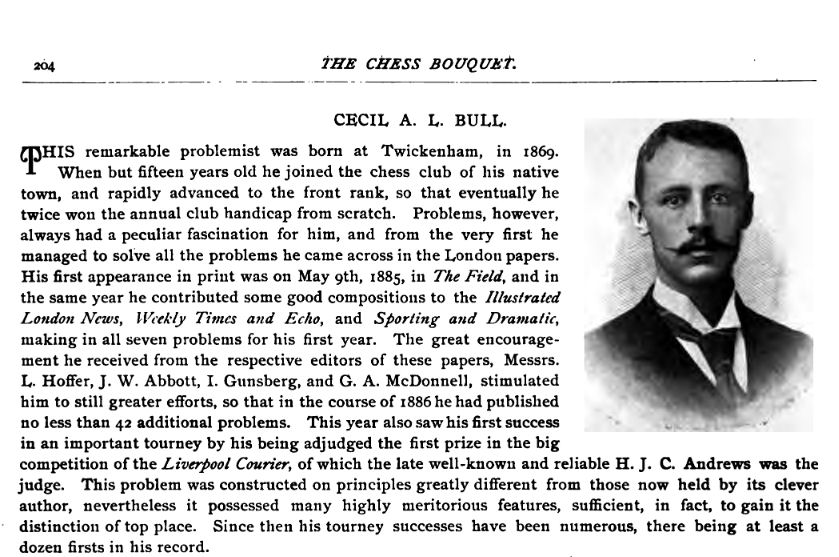

Even at that point, he’d been active elsewhere in the chess world for some time. His first problem was published in The Field in May 1885, just before his 16th birthday. It soon became clear that he was both exceptionally knowledgeable about chess problems and had a remarkable talent as a composer.

His first prize in the Liverpool Weekly Courier in 1886 caused a sensation and also a bit of controversy at the time.

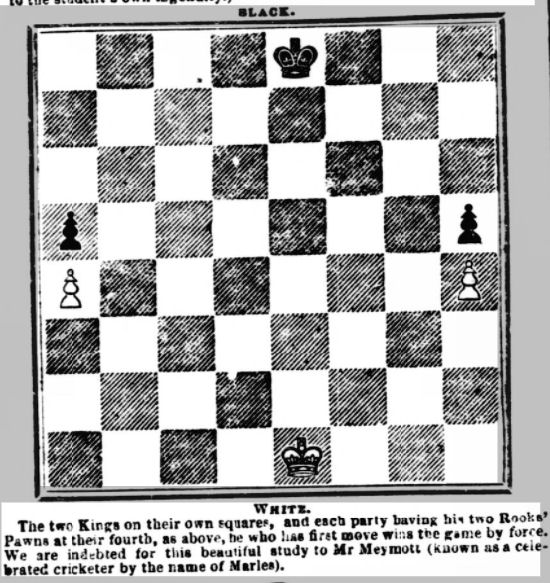

Problem 1. White to play and mate in 3 moves. Solution at the end of the article.

Although he published a few mates in 2 and longer mates, and also a few selfmates, most of his problems were mates in 3. His younger brothers Clifford and Walter also had a few problems published in their teens, but seem not to have continued their interest.

As well as blockbusting prizewinners, Cecil had a knack for composing crowd-pleasing lightweight problems which would have been attractive to over-the-board players.

Problem 2, another mate in 3, was published in the British Chess Magazine in 1888.

Chess wasn’t young Cecil’s only game. From 1888 onwards we find him playing cricket for a variety of local clubs: Strawberry Hill, Teddington, East Molesey, Barnes before settling on Hampton Wick. He was a talented all-rounder, excelling with both the bat and the ball. (I’d have called him both a bowler and a batsman, but today, in the spirit of political correctness, we’re expected to use ‘batter’ instead. I’m afraid it just makes me think of Yorkshire pudding, though.) His teammates sometimes included his older brother Alan, and Edward Albert Bush, who, in 1891, married his sister Beatrix. I do hope they celebrated at the Bull & Bush.

Problem 3 is another prize winner: this one shared 2nd prize in the Bristol Mercury in 1890. Again, it’s mate in 3.

By 1891 the Bulls had moved again. They were now in Walpole Gardens, just by Strawberry Hill Station, with Beatrix, Maud, Gwynneth, Clifford, Walter and their youngest son, Basil. I haven’t been able to find Allegra in 1891. There were now only two servants. Did they need less help as their children grew up?

Cecil was in Bloomsbury in 1891, living ‘on own means’ in the home of a classics teacher who also took in boarders. It seems that he was wealthy enough not to need a job, so was able to devote his time to his hobbies of chess and cricket.

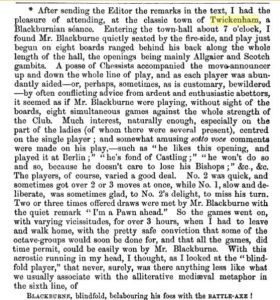

Here’s how FR Gittins would describe his early life in The Chess Bouquet.

And then, in 1892, everything changed. Julia died and the family started to disperse. Walter emigrated to America, where he would later be joined by Basil. Cecil, because of his passion for cricket, soon set sail for South Africa, where Clifford would later join him. It’s possible that the oldest brother, Julius, also emigrated to South Africa, but this is at present uncertain.

Meanwhile, Thomas married a widow named Margaret Crampton in Steyning, Sussex in 1895, and by 1901 they were living in Chingford, Essex. Clifford was the only one of his children still living with him. I haven’t yet been able to find the family in the 1911 census: I suppose it’s quite possible they were visiting one of Tom’s children in America or South Africa. It looks like Thomas Bull died in Chelsea in 1918 at the age of 78.

Do you want to find out what happened to Cecil in South Africa? I’m sure you do. Don’t miss our next exciting episode.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

Ancestry

Findmypast

Wikipedia

Problems and solutions taken from Yet Another Chess Problem Database.

Thanks to Dr Tim Harding for The Chess Bouquet.

Solutions to problems:

1.

1.♖d4! 1…♖d1 (R~1) 2.♕×e2+ ♕e3 3.♕×e3# 1…♕f1 2.♖e4+ 2…f×e4 3.♕×e4# 2…♔×d5 3.♘e3# 3.♕d3# 2.♕×f5+ ♔×f5 3.♗d7# 1…♕g2 2.♕×f5+ ♔×f5 3.♗d7# 1…♕g4 2.♖e4+ 2…f×e4 3.♕×e4# 2…♔×d5 3.♘e3# 3.♕d3# 1…♕h1 2.♕×f5+ ♔×f5 3.♗d7# 1…♕h2 2.♕×f5+ ♔×f5 3.♗d7# 2.♖e4+ 2…f×e4 3.♕×e4# 2…♔×d5 3.♘e3# 3.♕d3# 1…♕a3 (Qb3, Qc3, Qf3, Qg3) 2.♕×f5+ ♔×f5 3.♗d7# 1…♕d3 2.♖×d3 ♖a1 (R~1) 3.♕×e2# 1…♕e3 2.♘×e3 ~ 3.♕×f5# 1…♕×h4 2.♕×f5+ ♔×f5 3.♗d7# 2.♖e4+ 2…f×e4 3.♕×e4# 2…♔×d5 3.♘e3# 3.♕d3# 1…c×d4 2.♘e5 ~ 3.♗f7# 2…d×e5 3.♕c6#

2.

1.♔f8! ~ 2.♘c7 ~ 3.♕d4# 2…♗c4 3.♕a3# 1…♔d5 2.♕d4+ ♔e6 3.♘g7# (Model mate, Mirror mate) 1…♗c4 2.♕a3+ 2…♔d5 3.♕d6# 2…♔b5 3.♘c7# (Model mate)

3.

1.♕h3! ~ 2.♕f5+ ♔c6 3.♖c4# 1…♗×e4 2.♕c8 ~ 3.♘c3# 2…♖c6 3.♕g8# 1…♗d3 2.♕c8 ♗×e4 3.♘c3# 1…♔c6 2.♕c8+ ♔b5 3.♕c4# 1…♔×e4 2.♕g2+ 2…♔f5 3.♕d5# 2…♔d3 3.♘b2# 1…b5 2.♖d4+ ♔c6 3.♕c8# 1…b6 2.♘c3+ 2…♔c5 3.♕c8# 2…♔c6 3.♕c8#