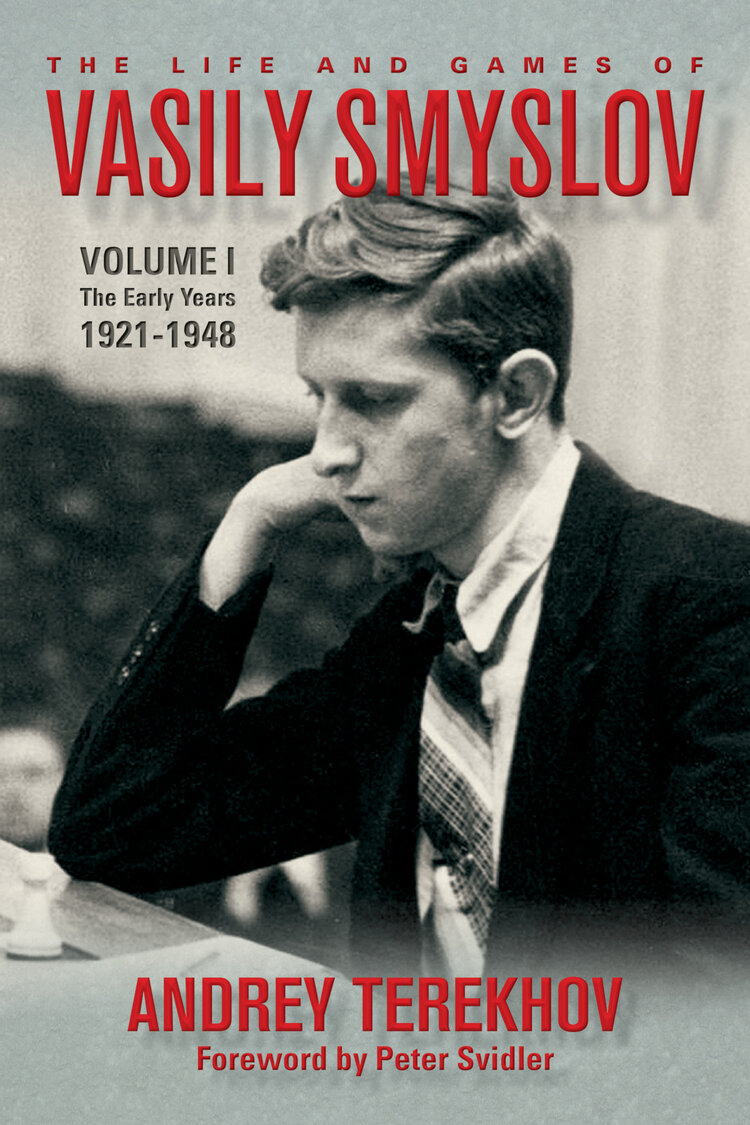

From the publishers blurb:

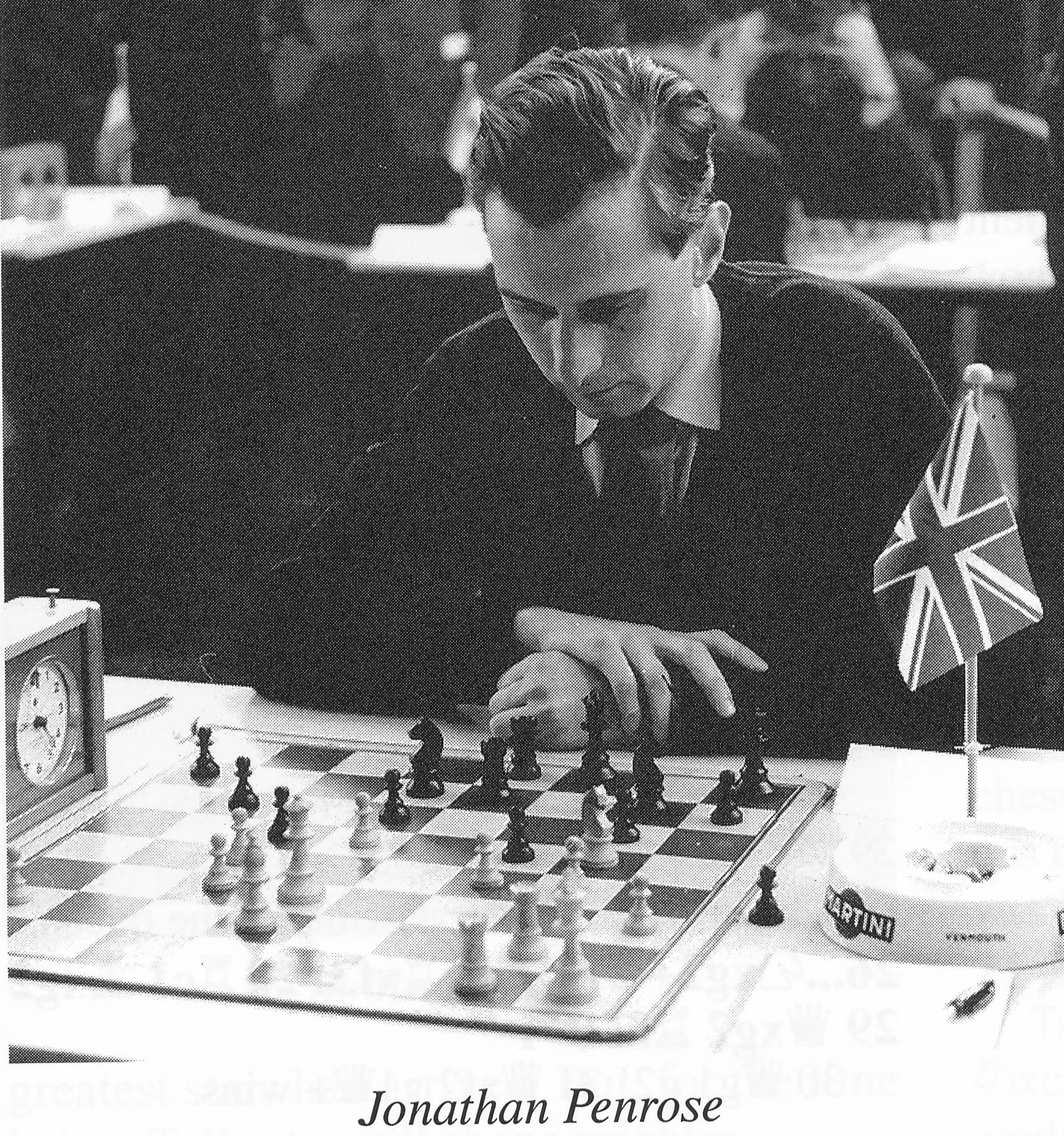

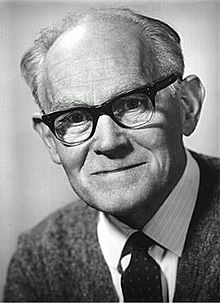

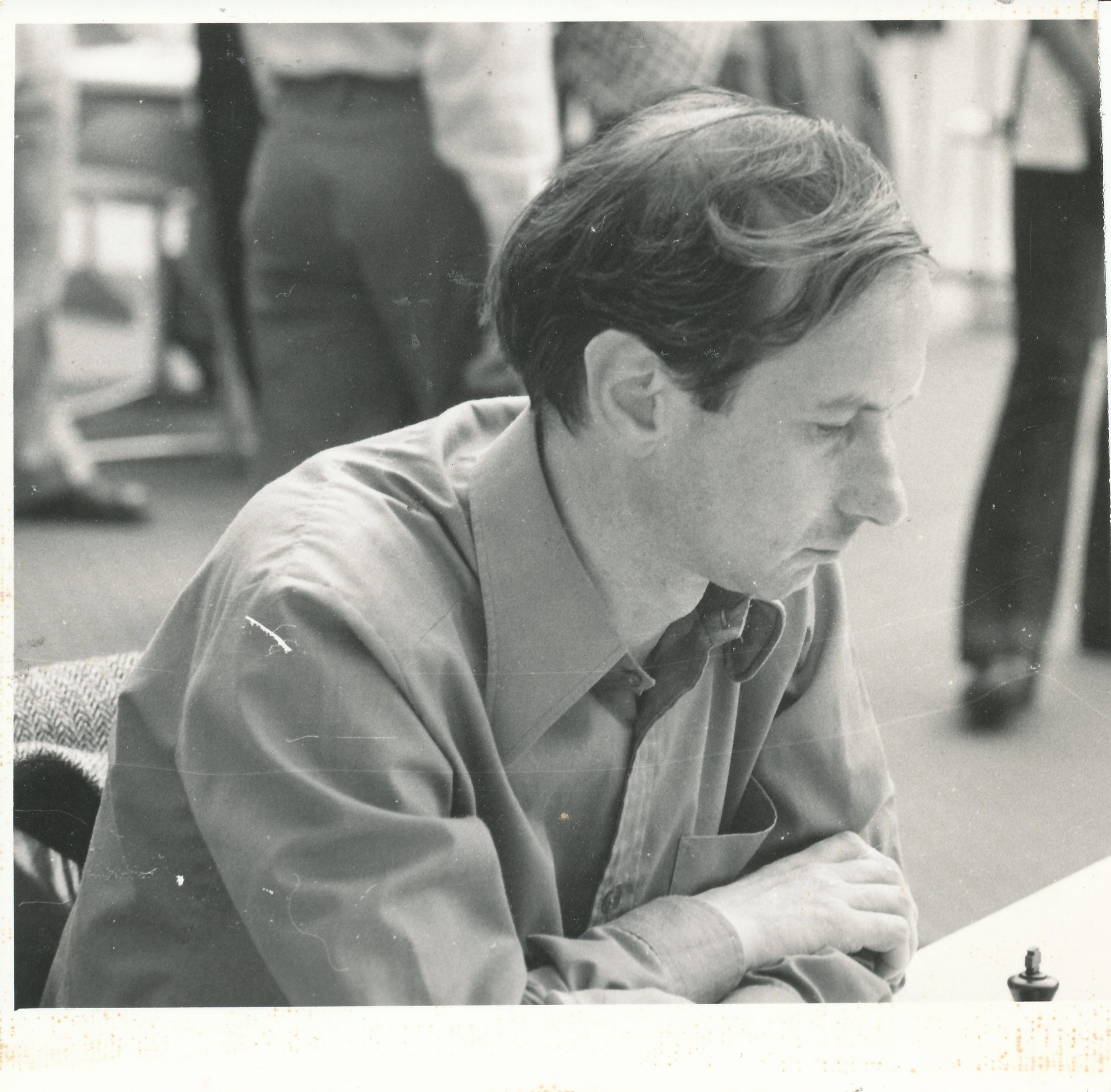

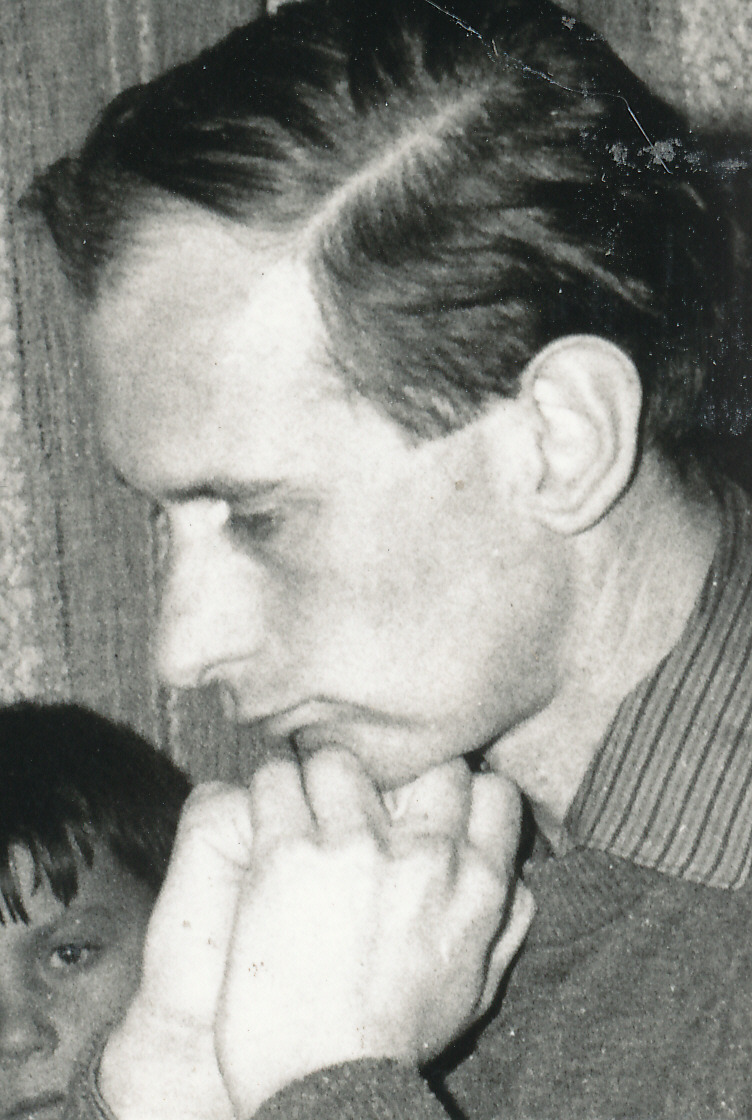

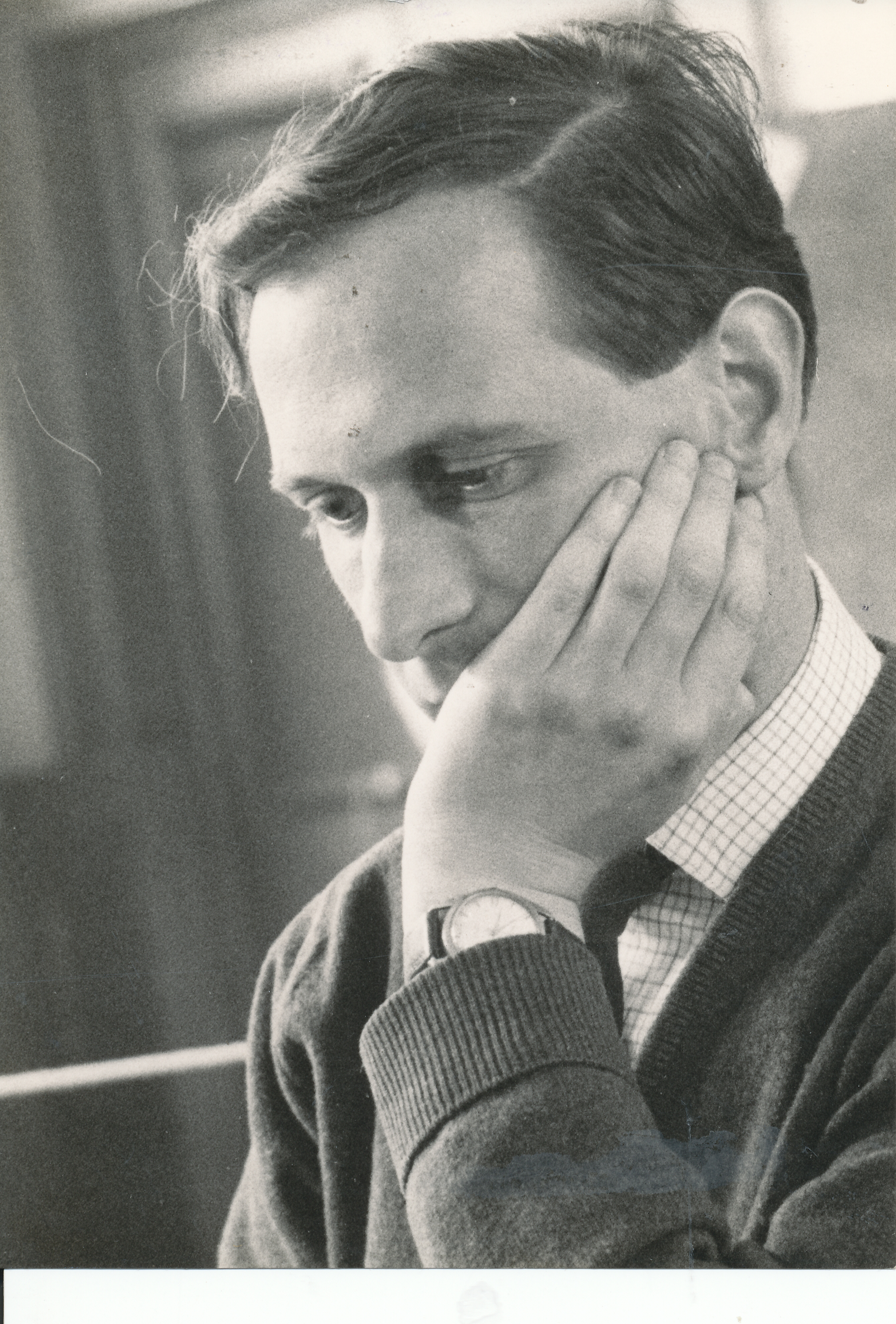

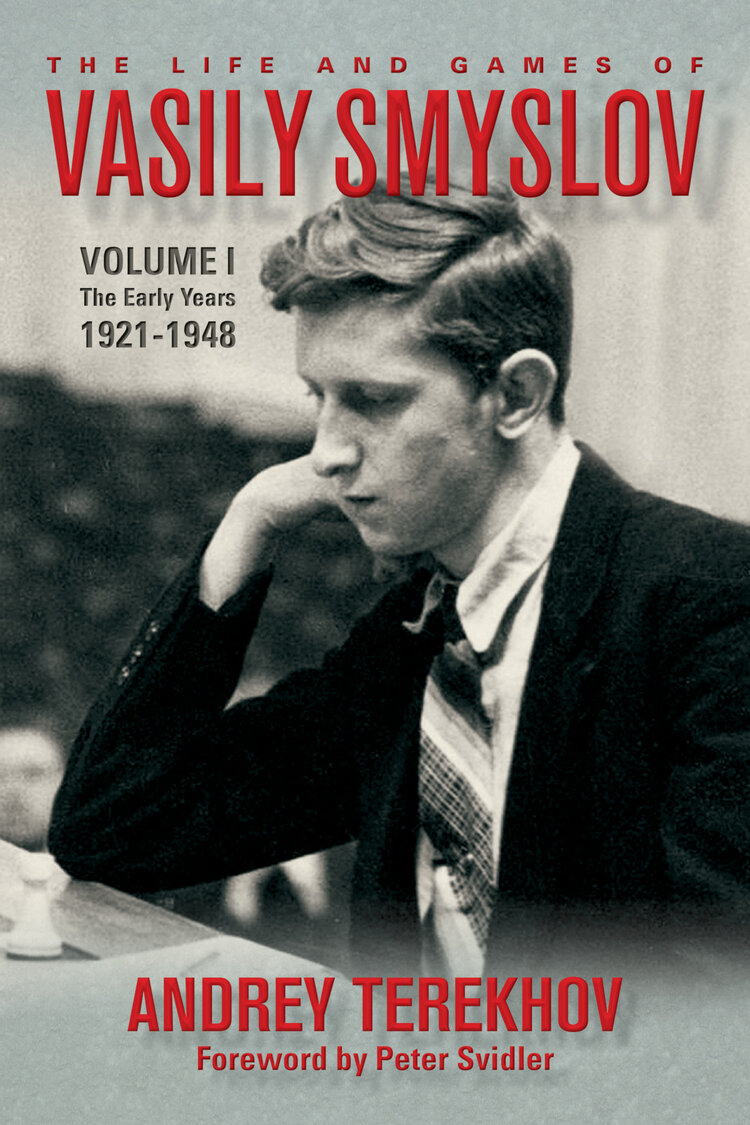

“Vasily Smyslov, the seventh world champion, had a long and illustrious chess career. He played close to 3,000 tournament games over seven decades, from the time of Lasker and Capablanca to the days of Anand and Carlsen. From 1948 to 1958, Smyslov participated in four world championships, becoming world champion in 1957.

Smyslov continued playing at the highest level for many years and made a stunning comeback in the early 1980s, making it to the finals of the candidates’ cycle. Only the indomitable energy of 20-year-old Garry Kasparov stopped Smyslov from qualifying for another world championship match at the ripe old age of 63!

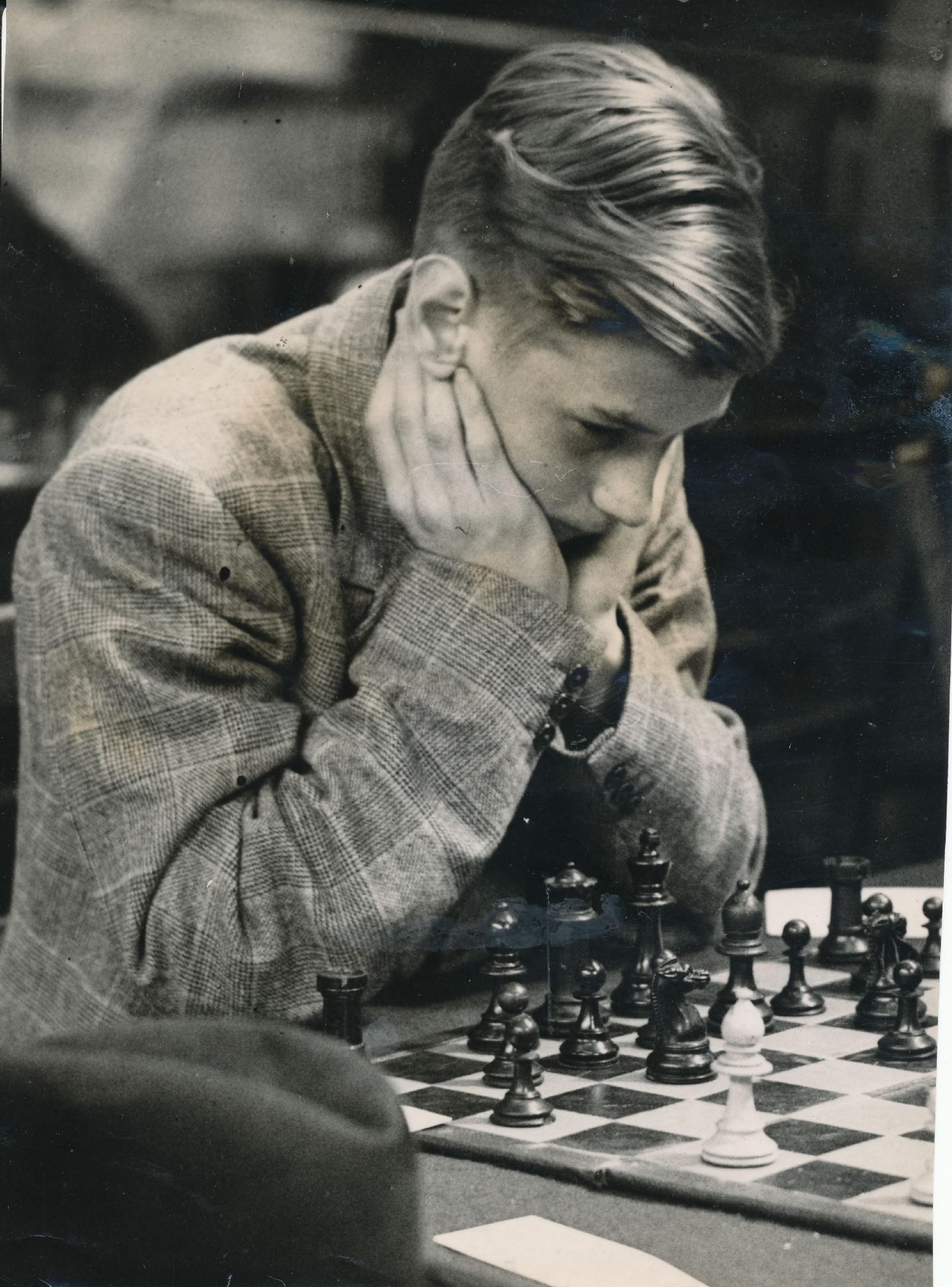

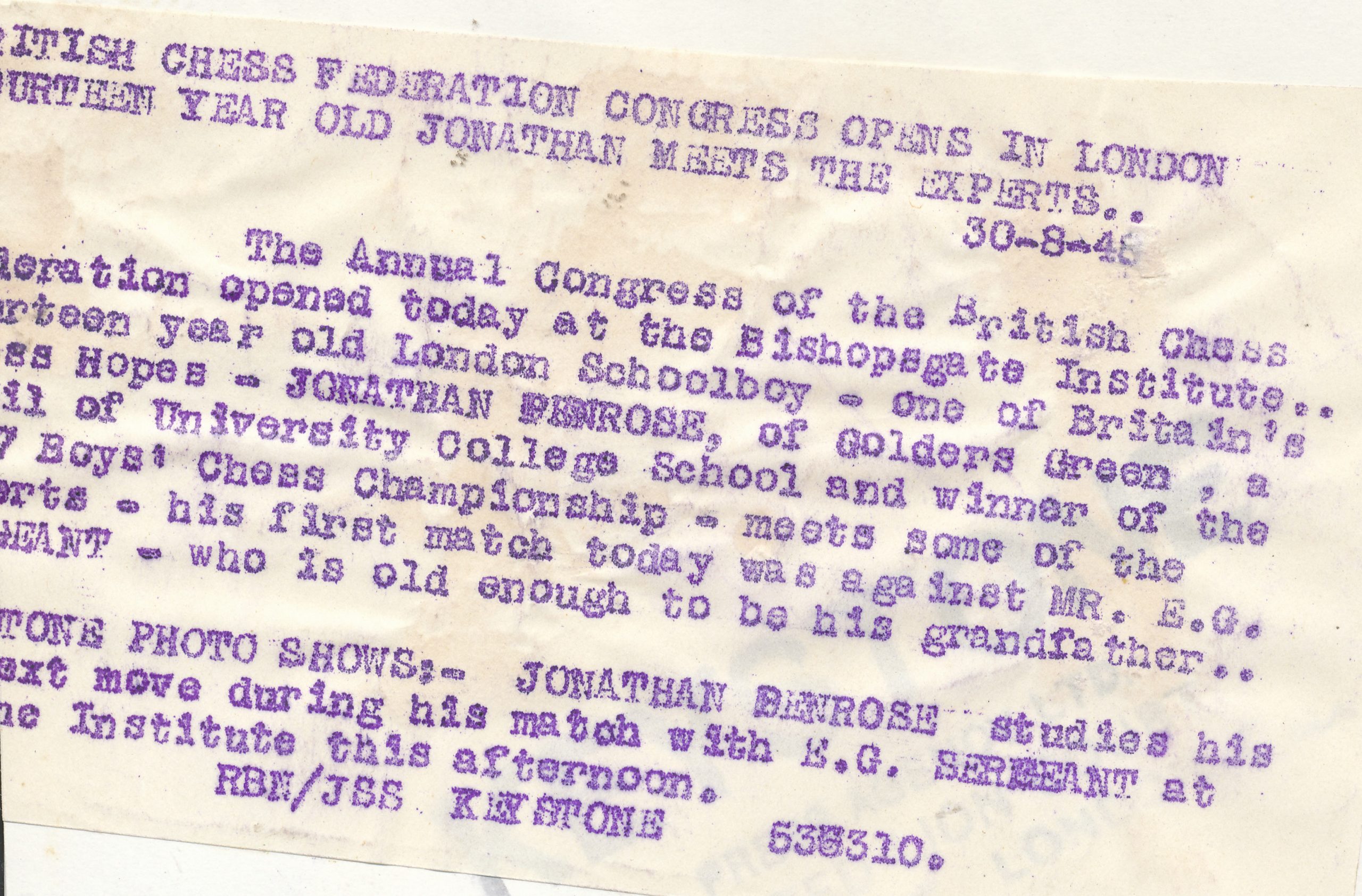

In this first volume of a multi-volume set, Russian FIDE master Andrey Terekhov traces the development of young Vasily from his formative years and becoming the youngest grandmaster in the Soviet Union to finishing second in the world championship match tournament. With access to rare Soviet-era archival material and invaluable family archives, the author complements his account of Smyslov’s growth into an elite player with dozens of fascinating photographs, many never seen before, as well as 49 deeply annotated games. German grandmaster Karsten Müller’s special look at Smyslov’s endgames rounds out this fascinating first volume.”

I’ve always considered Vasily Smyslov (1921-2010) one of the more underrated world champions. I enjoy the combination of logic and harmony in his games along with his endgame expertise, so I was looking forward to reading this book.

Terekhov suggests in his introduction that Smyslov is arguably the least known of all world chess champions.

Perhaps the primary reason for Smyslov’s relative obscurity was his character. Smyslov was a reserved and deeply private man who did not strive for the spotlight.

And again…

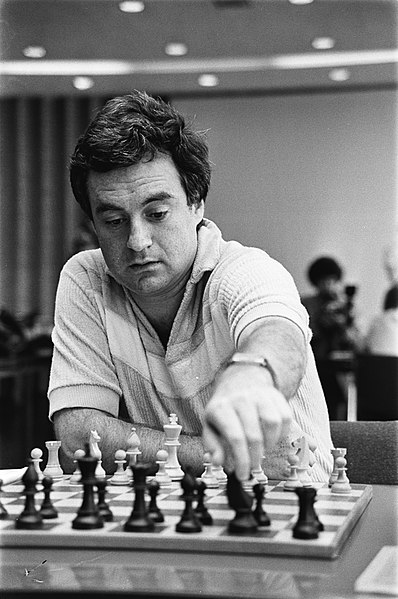

Another factor was Smyslov’s playing style, which was classical and logical, but not necessarily flashy. To make a comparison, both Smyslov and Tal were world champions for only one year, but Tal won millions of fans for his dashing style and remains an iconic figure to this day, whereas Smyslov’s popularity largely waned after the period when he held the championship.

Up to now there have been few books, apart from those written by Smyslov himself, about his games, and they have limitations, partly because they were written in the pre-computer age and partly because they lacked biographical detail.

A few years ago, I decided to write a book that would fill in these blanks. Initially, it was conceived as a traditional best games collection, interspersed with a few biographical details. However, it quickly became apparent that Smyslov’s long chess career cannot be covered in a single volume. I amassed an extensive library of books, tournament bulletins and magazines which cover Smyslov’s chess career from the 1930s onwards. I also kept unearthing new material, including Smyslov’s manuscripts and letters.

What we have here, then, is the first volume of a hugely ambitious project, a combination of biography and best games collection, taking Smyslov’s career from his first competitive games in 1935 through to the 1948 World Championship Match-Tournament. A second volume will take the story up to 1957, when he became world champion, and further volumes will cover the remainder of his career, up to his last tournament games in the 21st century and the endgame studies he composed towards the end of his life.

What you don’t get is Smyslov’s complete games: you’ll need to look elsewhere if you want them.

The book comprises ten chapters, each covering a different part of Smyslov’s career. Each chapter in turn is divided into biography and games.

There are 49 complete games in this volume, all annotated in considerable depth. Terekhov has used an impressive range of sources: Smyslov’s own annotations, Soviet chess magazines and other contemporary sources, later commentators such as Kasparov, and skilfully combined these with computer analysis using today’s most powerful engines. Many annotators make the mistake of going overboard with reams of computer-generated variations, but Terekhov avoids this pitfall. While not everyone wants this sort of detail, the annotations in this book are some of the best I’ve read. A nice touch is that you also get brief biographical notes on his opponents.

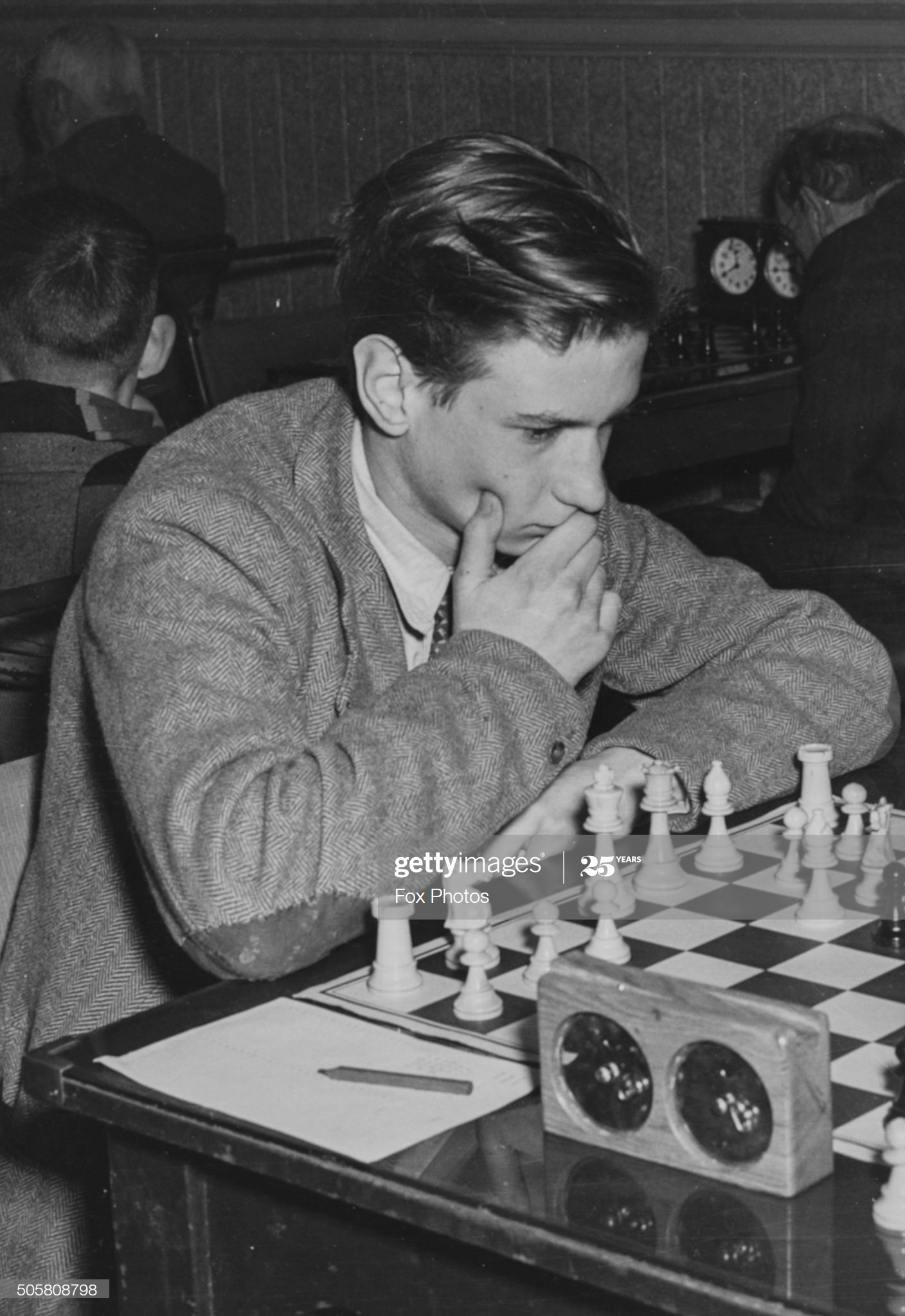

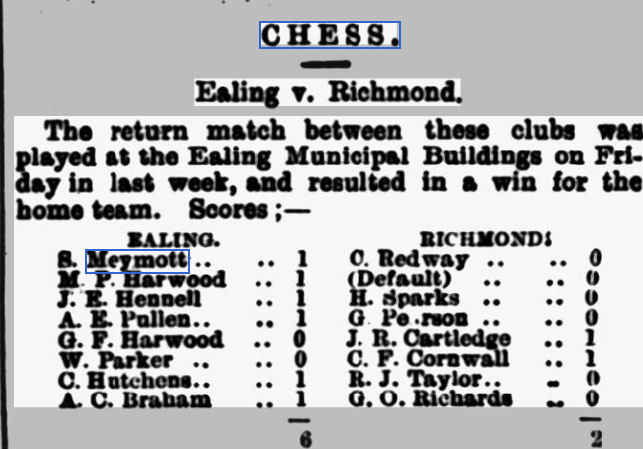

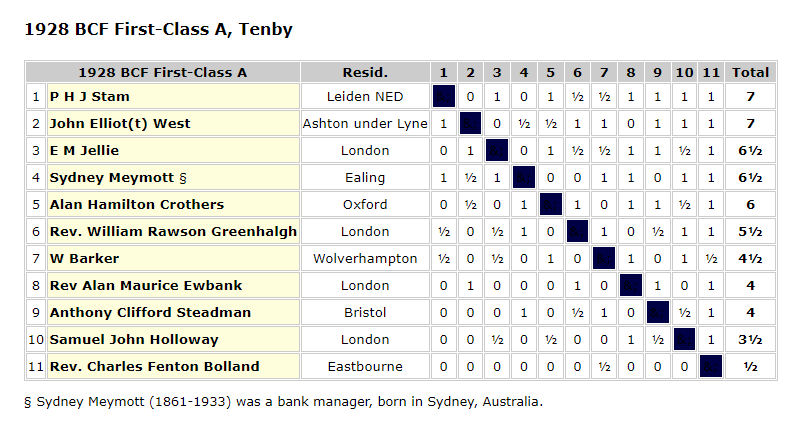

The scope of the biographical sections, too, is impressive. There’s a lot of fascinating material from Soviet sources with which most readers will be unfamiliar. You’ll learn a lot from this, not just about Smyslov’s life, but also, in general, about how chess in the Soviet Union was promoted and organised in the 1930s and 1940s. You’ll expect full reports of the tournaments Smyslov played in, along with cross-tables. They’re all there, along with much more chess: many snapshots from games, some endgame studies, all illustrated with a profusion of photographs, many of which will be new to most readers. There’s plenty there to keep every chess lover happy.

Let’s look at a couple of the snapshots.

Here’s a remarkable position from the game Panov – Smyslov 12th USSR Championship 1940 demonstrating his defensive skills.

Smyslov continued with the extraordinary 19… Nc6!!?.

This desperate move evokes the memories of Spassky’s famous Nb8-c6 in a strategically lost position against Averbakh (Leningrad 1956), but Smyslov came up with the idea 16 years earlier!

20. dxc6 bxc6 21. Ba4 Rcb8 22. Qxa3

At first glance, White is completely winning, as he is a bishop up and Black does not even have a single pawn to show for it. However, even the engine agrees that Black has some initiative in exchange for the piece, although far from full compensation.

Smyslov eventually won this game after Panov blundered on move 41. If you buy the book you’ll see for yourself what happened.

In the 1941 USSR Absolute Championship, Smyslov found himself a pawn down in a minor piece ending against Lilienthal.

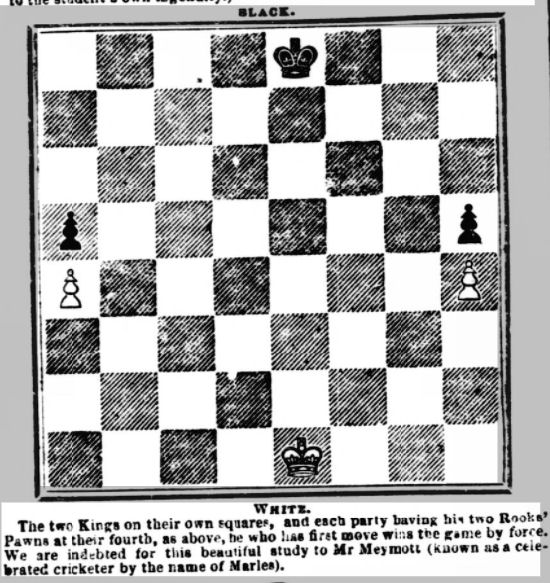

At some point, Smyslov took a brilliant, although practically risky decision to sacrifice both of his pieces for the remaining Black pawns. The game transposed to the following rare endgame, which was studied in great detail by the Russian composer Alexey Troitsky:

This position was evaluated by Troitsky as a draw and modern tablebases confirm this assessment. However, defending this position in practice is no fun, as a single bad move can lead to a forced mate. Smyslov managed to hold it and the game was agreed drawn on the 125th(!) move.

But there’s much more than chess in the biographical sections. The game was so popular in the Soviet Union that Smyslov received fanmail from young female admirers, some of which have survived. Here’s Klara, writing to her hero in 1941. Can you send me a photo of yourself, even if a tiny little one, but with your signature? If you cannot give it to me, please send it to me so I could take a look – I will return it. If you only knew how I want to see you, hear you talk – but alas – these are just dreams which cannot come to life for at least another year…

Most poignantly, we have a letter Smyslov wrote to the mother of his friend Bazya Dzagurov in 1942, asking for news of her son, who had been serving in the war. How are you doing? Do you have anyone left by your side? Is there any information about Bazya? I heard that you have not received letters from him for a long time, but I don’t know anything for certain. Please write to me about your life and let me know something about your son and my friend. Tragically, Dzaghurov had lost his life several months earlier.

Right at the end of the book there are a few bonuses. Chapter 11 introduces us to Smyslov’s wife Nadezhda Andreevna, Appendix A covers the Smyslov System in the Grünfeld Defence, and Appendix B, contributed by GM Karsten Müller, tells us more about Smyslov’s Endgames.

Here are a couple of short game which you’ll find annotated in the book. Click on any move for a pop-up board.

Although Smyslov’s fame rests mainly on his positional and endgame skills, he could still play aggressively when the opportunity arose, and some of his earlier games featured here are quite complex.

In this game (Moscow Championship 1939) he scored a quick attacking victory against the now centenarian Averbakh.

Here’s a highly thematic game from the 1945 USSR Championship.

I’ve said before that we’re living in a golden age of chess literature. There are several reasons for this, two of which are relevant to this book. Firstly, we have much greater access to archive material than ever before, and, secondly, powerful modern engines ensure accurate analysis. This is an outstanding and important work which should be on the shelves of anyone with any interest at all in chess history. Excellent writing, painstaking research and exemplary annotations, along with first class production values (barring the inevitable one or two typos and errors): the book is an attractive and sturdy hardback which will look good in any library.

Congratulations are due to Andrey Terekhov, and also to Russell Enterprises. Very highly recommended. I can’t wait to read the next volume in the series.

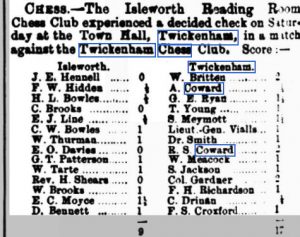

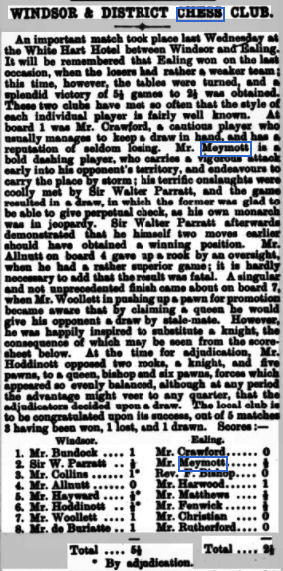

Richard James, Twickenham 3rd March 2022

Book Details :

- Hardcover : 536 pages

- Publisher: Russell Enterprises (1 December 2020)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10:194985924X

- ISBN-13:978-1949859249

- Product Dimensions: 15.24 x 2.54 x 22.86 cm

Official web site of Russell Enterprises